Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Hirschauer1995 Shifting Sexes, Moving Stories FeministConstructivist Dialogues

Enviado por

yoginireaderDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Hirschauer1995 Shifting Sexes, Moving Stories FeministConstructivist Dialogues

Enviado por

yoginireaderDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Shifting Sexes, Moving Stories:

Feminist/Constructivist Dialogues

Stefan Hirschauer

University of Bielefeld

Annemarie Mol

University of Limburg

How can constructivism and feminism inform and strengthen one another? The author

of this text is a constructivist-feminist hermaphrodite, and so s/he addresses this question in

the form of an inner dialogue. Instead of taking sex as a characteristic of individuals, s/he

analyzes it as something performed locally in ways that vary from one situation to

another. Investigating these performances offers constructivism an interesting theoreti-

cal opportunity and a chance to turn away from a sterile anti-epistemological stance.

For feminism, a radicalized notion of the construction of sexes opens up new political

spaces and strategies. Constructivist texts, moreover, have the potential to "do" both the

contingency and the necessity of our forms of life in their very style.

Prologue

A: Let us begin by giving the reader some information about our sex, race, class,

and maybe some other things, too. We had better make it clear right from the

start from which standpoint we are speaking.

B: But this isnt a statement to the police, is it?

A: What do you mean? I dont like you to make fun of me.

B: I am dead serious. Why cant I just write without being asked for my identity

papers?

A: Because you cant! People read differently when they know who is addressing

them. They want to know. And they especially want to know whether you are

a man or a woman.

B: Do they? Not always. It must depend on the specific case. Do you think this is

so for readers of Science, Technology, & Human Values? Lets see.

AUTHORS NOTE: We thank the participants of the Conference on Constructivism and

Feminism in Brunel, September 1993, especially Janet Rachel for her encouragement and

Malcolm Ashmore for his subtlety. We are also grateful to the anonymous reviewers of this journal

for their comments and to John Law for facilitating our submission to the English language

Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol 20 No 3, Summer 1995 368-385

@ 1995 Sage Publications Inc

368

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

369

1

He: I suggest that before we get started, we negotiate about our sexes.

She: Only a man could ever come up with an idea like that!

He: Why? An open negotiation ...

She: Listen, over and over again, women experience the fact that there is no choice

at all in these matters. And you will never get that. You have never had the

experience of being turned into a woman. By others. So we cant just freely

chat and &dquo;decide&dquo; about something like our sexes.

He: Do I hear a complaint in your tone of voice? You are not suddenly into

victim-talk, are you? Please, stop it! Isnt it about time to try something new?

She: Hmm. All right. As an experiment. On one condition: that the outcome of the

negotiation is that I take the male voice.

He: Thats fine with me. Good luck.

She: I suggest that before we get started, we negotiate about our sexes.

He: Only a woman could ever come up with an idea like that!

She: Why? It could be nice, couldnt it?

He: Nice! Listen, you feminists have gone too far. You have really started to believe

these theories of yours. Dissolving the sex-gender distinction. Sociologizing

&dquo;sex&dquo; to an impossible degree.... I mean, you cant deny the biological facts

of life and claim everything is possible, a matter of choice, something to be

negotiated about.

She: Do I hear conservative undertones, even anxiety, in your voice? Please, dont.

Stop it. Isnt it about time to try something new?

He: Hmm. All right. As an experiment. On one condition: that the outcome of the

negotiation is that I take the female voice.

She: Thats fine with me. Good luck.

Introduction

If I write this article as a contribution to a dialogue between feminism and

constructivism, I am in the confusing situation that I must first split myself

up analytically into the two parts I will have to put together later. If construc-

tivists and feminists are invited to write in this journal, I feel I am being

offered a choice that generates anatomical problems.

He: Do we really want to make such a confessional start? To talk about who and

what we feel ourselves to be? We just tried to confuse our readers about our

identity, and now we are offering them yet another set of labels that they might

use to categorize us.

She: Youve missed the point. In refusing the choice between being a

constructivist and being a feminist, we claim to be a hybrid. And, like changing

sides in a system that has only two categories, being a hybrid also subverts

categorizations.

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

370

He: Okay, Im sorry I need to have this to Fine. Lets go But it

hurts in my pnvate parts ... it really

explained

does.

me. on.

A few years of fieldwork in the subcultures of both science and technology

studies and womens studies allows me to present a list of attributions

circulating in each of these circles about the other. These labels are not

necessarily written down in the literature, which is often less frank than the

spoken word.

Feminists state that the constructivist mainstream in science and technol-

ogy studies is gender blind. It does not see that men and women, not &dquo;people,&dquo;

work in the laboratories. Or that &dquo;users&dquo; also have a sex. And constructivism

is elitist. It has no political relevance. Or it is simply far too liberal. Or, yet

again, it is not serious.

Constructivists complain that feminist work is boring and predictable. You

always know &dquo;whodunit&dquo; right from the start; the plot is far too flat. Feminist

epistemology, moreover, contains oddities that are the sad outcome of its

political preoccupations-for example, selective relativism. Some things

may be made, but not others. Oppression and domination are assumed from

the outset, and they are serious.

I do not plan to explore the extent to which these attributions are true.

Instead, I want to take them as a point of departure. And move ahead.

He: Do you think our readers will believe our ethnographic account? Maybe they

will insist that we explore further the arguments used. And give proper

quotations and citations. There must be some.

She: Of course there are. But the readers know perfectly well what we are talking

about! After all, they are ethnographers and members of these tribes them-

selves. Moreover, they know all about the way in which footnotes are a

3

legitimating practice.

He: I dont doubt that they do, but just knowing that something is constructed,

contingent, a power game, does not mean that you can do away with it so easily.

4

Nobody will read us unless we show that we have done our homework.

She: So this is another version of our problem, isnt it: does knowing that

something is &dquo;constructed&dquo; make a pohtical difference or not? To what extent

are constructions malleable?

He. Good question, but what to do here and now? If we create footnotes, is this a

political defeat? A loss of origmality?5 Or a nice, helpful gesture to our

readers ?6

Even if constructivism and feminism are not always good friends, we want

to argue here that they are not necessarily contradictory. They might even

inform and strengthen one another.

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

371

Sex Is Everywhere-Different

If, despite exceptions, feminists are usually right in reproaching science

and technology studies for forgetting about the sexes, then something strange

is going on: not a lack of political correctness, but a flaw in the quality of

observation. In addition, science and technology studies are missing out on

a good opportunity for theorizing.

There is so much &dquo;sex difference&dquo; around. How do all these intelligent

scholars manage to overlook it? If you have met people and you try to

remember them, you may have forgotten their names and their addresses,

their contributions to a funny event, and even their interesting theoretical

arguments, however much you wanted to keep that in your head. But, in each

instance, you will remember whether you met a man or a woman. Sex is the

very last thing people forget about each other. To have ones sex forgotten is

tantamount to disappearing from someones memory.

He: I wonder why so many of these laboratory anthropologists overlook the sexes

of the scientists and technicians they study-or that of the secretaries they do

not study, for that matter.

She: They also overlook the sex of non-humans: skeletons, storms, nature, toilets.

But, then again, lets remember: sex isnt quite everywhere. English language

elevators, for instance, have no sex.

He: Elevators?!

She: Didnt I tell you? I think that the way various languages use pronouns largely

explains the international quarrel about non-human actors. This idea struck me

in the United States in an elevator. I tried to be as sociable as the natives. So I

said, &dquo;Gee, he goes very slow, doesnt he.&dquo; And nobody understood that I was

talking about the elevator. In English, an elevator is not a &dquo;he.&dquo; After a long

while, someone said, &dquo;Oh, you mean it goes slowly; yes, it does.&dquo; An English

speaking elevator is an &dquo;it.&dquo; In French, elevators have a sex. They are &dquo;ils,&dquo;

which makes it far easier to attribute laziness or activity to them.

The relevance of having a sex is variable. The sex of an individual is harder

to forget than that of a storm. The sex of a lover will matter more than that

of a neighbor in the train. But this relevance is contingent. To know about

the relevance of sex, one has to go out and investigate the movements of the

bodies of male and female students at a bench doing laboratory work; the

attribution of clever remarks to some people and not others; the metaphors

of war, knitting, and house cleaning.

She: But listen. Emily Martins (1994) story describes how immunology contains

different ways of talking about the immune system. One is violent: the immune

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

372

system is like a defensive army or a secret police that has to keep strangers out

or detectthem once they are inside. And the other is to talk of household duties:

the mast cells that eat the dirt away and clean the mess in every comer of the

body.

He: You are trying to credit science studies with that, are you? Martin is an

not

anthropologist. She is a feminist, isnt she? So that story may be about science,

but it comes right out of feminism.

She: Arent you creating anatomical problems for someone else now?

If constructivist studies of science and technology have not explored sex as

much as they might have, this could be changed in the future. Constructivism,

after all, is a strong tool. It can tell about the construction of anything:

neutrinos, microbes, airplanes, scallops, genes, hormones, bicycles, and so

on. The construction of any object can be traced. So why not that of the sexes?

But the issue is not one of completeness. Just adding the sexes to the list of

constructed objects would be too easy. Arent these lists losing their appeal?

They become longer and longer each year. Every new Ph.D. student, every

new summer grant, adds another case. But what is at stake? Not the neutrinos,

microbes, airplanes, scallops, genes, hormones, and bicycles that are made,

but the process of making them scientifically. Only epistemology is ques-

tioned. Each story tells in yet another way that knowledge does not emerge

from its object, that representation is a laborious process, that facts are

artifacts, that artifacts are put together, and that efficiency is not the driving

force but is something that takes shape along the way.

This has become so true that repeating it begins to look like a formality.

So where do we go from here? Focusing on the sexes may help to shift the

attention of constructivists from method to object. It is not the fact that the

sexes are constructed that makes them intriguing, haunting, and important

but rather what they are made to be. This is what gives them their political

relevance-but also offers theoretical promise. The sexes are made to be so

many things. There are sexes everywhere, or almost so, but they are different

everywhere, or almost so. Studying this construct in various places may

reveal links between these places-but also may reveal fractures, alliances

and conflicts, resonance and dissonance.

An Example

Anatomy tells us that there are two sexes. Every body can be categorized

as one or the other. If you look between their legs, you may see that some

bodies have penises whereas others have vaginas. The former, or so anatomy

tells us, fit into the category &dquo;male&dquo; and the latter into the category &dquo;female.&dquo;

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

373

If you are armed with some knowledge of genetics and histology and

examine through an electron microscope the nuclei of some cells scraped out

of the oral cavity of humans, you may see that in some cases the nuclei contain

a structure that looks somewhat like the letters XY, whereas in other cases

there will be a structure that looks like the letters XX: two classes of

chromosomes, two categories.

Endocrinology works differently again. It tells about two kinds of hor-

mone levels, the balances between them, and the rhythms with which they

change. If you want to determine the sex of individuals by endocrinological

means, you take samples of their blood and put them through a chemical test

called &dquo;radioimmunoassay.&dquo;

An important strand of psychiatry argues that sex is a question of self-

identity. You are what, deep down, you believe yourself to be. You can find

out what individuals believe themselves to be by interviewing them about

their biographies and feelings or by giving them questionnaires full of

indiscreet questions.8

What kinds of relations obtain among these practices? In some instances,

we find dependence: anatomy is instrumental in making endocrinological

sex. When normal values for blood samples in radioimmunoassays are set

up, the samples are classified in terms of the anatomical sex of the donors.

Conflict may, however, arise later: once the normal values are established, an

individual may be categorized as an endocrinological male even though s/he

has a vagina or as an endocrinological female even though s/he has a penis.

There are also relations of supremacy: whether one may compete in the

Olympic Games as a woman or not depends on ones genes. Individuals with

Y chromosomes could not pass as women even if they had female anatomies.9

Complicated relations between various constructions are also found in the

treatment trajectories of people who want to change the sex attributed to them

at birth. To move officially from one side of the sex boundary to the other,

one first has to fit into the psychiatric category of the opposite sex. She has

to feel a he, and he has to make the therapist believe he is a she inside by

telling stories and displaying &dquo;appropriate&dquo; appearance and conduct. If this

is successful, then the endocrinologists look to see whether one is endocri-

nologically normal and, if so, then endocrinological sex is changed by

hormone pills. Finally, surgeons may complete the job with an anatomical

alteration of the genitals.

Here the various constructs of sex relate in a sequence, although not one

that is obligatory. For some transsexuals, the psychiatric (re-)conception of

their sex is strong enough to define their sex for all practical purposes. They

do not need hormones and scalpels. Others use psychiatry only to establish

their rights to another (&dquo;the other&dquo;) body as the symbol of their true sex. These

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

374

differences are linked to legal constructions of the sexes, which may vary

from country to country. A transsexual woman in Germany who wants to

change sex legally and who wants to have a new official name has to have

major surgery. No legal females with penises are allowed. Dutch law does

not rely on anatomy but on the persons ability to procreate. In the Nether-

lands, a woman may have a penis as long as she does not produce fertile

semen. Juridical males, meanwhile, may have any organ they wish in both

countries-as long as they are unable to get pregnant. 10

She: Do you think our readers will catch the political significance of these

examples? They might think hybrids and transsexuals are too special.

He: I dont know. Maybe you are right. Insofar as they are sex normals, they might

find it easier to recognize the political nature of a different medical judgment

that is disappearing but that existed until very recently in South Africa.

She: You mean racial determination at birth, do you?

He: Yes. Try and list the differences and similarities between race and sex

determination!

So who are we made to be? What are the alternatives? There are links and

fractures: between anatomy and endocrinology, the law and chromosome

determination, a therapeutic session and the act of childbirth. Sexes are made

in so many ways, and because they may clash or reinforce one another, the

picture becomes astonishingly complicated. It makes no sense even to try

clustering these ways of defining sex into large domains such as &dquo;science&dquo;

and &dquo;society,&dquo; or &dquo;biology&dquo; and &dquo;sociology,&dquo; or &dquo;public&dquo; and &dquo;private.&dquo;

Because the constructions of the sexes are so diverse, it is also difficult to

make a single factor, such as &dquo;patriarchy,&dquo; responsible for them alL 11 Even if

there are patterns in the diversity. Even if there is not only dissonance but

resonance as well. How should we explain this theoretically? Are the sexes

not a good subject for those who want to try to articulate alliances and

frictions between a variety of practices without framing their questions in

terms of how science and society influence one another?

What Is Made, Can Change

The radical constructivist critique suggests that too many feminists cling

too much to theoretical positions that seem to offer security in politically

insecure places. But this is strange, as it implies that, for the sake of security,

feminists embrace a conservative strategy and give up rather than develop an

enormous political potential.

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

375

Most feminist strategies assume some constructivism, but all too often in

a weak form.I2 They assert that even if the individuals sex is given with their

bodies, their gender is constructed. This construction happened a long time

ago, in the dark ages of early childhood. It was a once-in-a-lifetime experi-

ence, beyond words, forever after out of reach. Psychoanalysis is mobilized

against anatomical, genetic, endocrinological, and other biological strategies

for defining sex. Biology is marginalized, not challenged. The factual status

of a persons gender is restated in the deployment of psychoanalytic terms:

you werent born a woman, but you became one, and now you are one.3

During the 1950s, turning gendered souls into substitutes for sexed bodies

might have been a good idea, but the sex-gender distinction is no longer

necessary. Instead of marginalizing biology, constructivism has the theoreti-

cal and practical tools to open it up and to show that anatomy, genetics,

endocrinology, and so on do not add up to form a solid biology, because they

also clash. Biology is no longer a safe place for non-feminists to hide and

count their well-established facts about the sexes.

Moreover, weak constructivism treats history as a time, now past, when

things were still unstable, whereas now they are black-boxed and stabilized.

But one may look at history as a chain of events that never comes to an end.

At any time, unexpected contingencies may divert the process of the con-

struction of the sexes into a new direction and make its outcome difficult to

predict. Therefore, individuals never safely &dquo;contain&dquo; their sex, and we

cannot treat it as an independent variable that explains others. Instead, we

can ask how sexes might vary or, if they do not, what kind of work is put into

keeping them stable or, again, how the process of making sexes is kept

going-for if it were not, the sexes might disappear altogether.I4

If one believed that individuals contained their sex, one might think that

male scientists seek objective knowledge because their mothers forced the

future scientists to become independent from them when they were babies,

or that an insecure search for autonomy leads men to make machines that

allow them to dominate the world around them.I5 But such explanations are

abandoned in radical constructivism. Look at that scientist or engineer over

there. Is this person a man? Nothing is certain. Maybe he is a man because

he became an engineer or because scientists constitute each other as males in

their homosocial culture.I6 But maybe she is not because she was never any

good at playing football. Or maybe, when s/he is a biologist, he is more male

than a sociologist but she is less so than a physicist. And, then again, our

scientist/engineer may have no sex at all. To escape from the position of the

potential object of male heterosexual desire-at least while working--he/she

has managed to neutralize himselflherself. Or s/he is neutralized by behaving

as the servant of an instrument and thus turned into an object.

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

376

It is all a matter of empirical detail. The sex of an individual may vary

from one site, and from one moment, to the next. It is something to go out

and investigate, not something on which to found an epistemology, especially

not a feminist one. If this radical movement means that security has been lost,

then something more interesting has been gained. The sex of individuals is

turned from a matter of fact into a contested performance, from a historical

given into something that is open to change, from something on which to

found a politics to something that is intrinsically political itself.

He: Some readers could misread us here, for to say that the sex of individuals is

an interesting variable does not mean it can be chosen at will.

She: Indeed. There may be resistance. We needed to negotiate a little at the

beginning.

He: Yeah, but that is not the whole story. Some aspects of the construction of two

sexes are pretty dense. The habit of distinguishing between two categories of

persons is incorporated into institutions and materialities, and this may stabilize

the construct to such an extent that it is not open to negotiation or individual

strategies at all.17

She: Sure, but that does not force us to fix a history and assume its stability. Lets

separate the idea of historical contingency and political struggle from that of

material stability and engineering control. 18 For instance, nobody orchestrated

the pulling down of the Berlin Wall, but it fell. And even if nobody was in

command, some political activities are likely to have helped. 19

I am not advocating now that feminists go out and investigate how individuals

are put into sex categories. It is not just that an individual may, at any specific

time and place, be put into one category, the other, or neither. These very

categories are not stable. If life histories may be full of open ends, shifts, and

changes, the same holds true for the history of categories.

The example of hermaphroditism shows nicely the instability of sex

categories over time. Hermaphroditism is an old Greek notion, suggesting

the existence of a double sex. It is lost. Since the eighteenth century,

anatomists have conceptually polarized the sexes, leaving no space for a

double sex.2 It became inconceivable that persons or bodies could integrate

both sexes. Therefore, people who previously would have been called her-

maphrodites were given the status of a male, a female, or someone between

the two sexes. In the latter case, they could not be both, but were in between:

an intersex. With this change, the law changed, too. Western European

countries lost a legal practice common up to the nineteenth century: that

people whose sex could not be decided at birth were to decide about their sex

themselves at the age of 18 in a court of law, swearing to remain true to their

choice thereafter. 21

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

377

So individuals may move from one category to the other, and categories

may change. But belonging to a category is not always the same thing either.

Whereas disciplines such as anatomy and genetics decide the sex of individu-

als by looking at them one by one, it is not always decided that way. Other

disciplines deal with bodies, but not with individual bodies.

Take anemia. There is nothing inherently sexed about this disease. In

hematology textbooks, anemia is defined as a hemoglobin level too low to

provide an adequate supply of oxygen to the tissues. Put in these pathophysi-

ological terms, a normal hemoglobin level differs from one person to the next

and has no sex. In current medical practice, however, anemia is not ap-

proached in a pathophysiological way but by means of statistics. Statistics

turns anemia into a sexed disease. Statistical practice builds on the anatomical

differentiation between the sexes and clusters hemoglobin levels of hundreds

of people identified anatomically as either males or females. Two curves

emerge. The median and cut-off point of the first are a little higher than those

of the second. Thus &dquo;men&dquo; have a higher normal hemoglobin level than do

&dquo;women. ,,22

No individuals sex can be determined by such statistical techniques. The

sex generated in this way is not one of bodies but is one of populations.

Individuals relate to it because their normality is often assessed by comparing

their hemoglobin levels to some population value or other. As a result, what

it means to be a woman is informed by the statistical knowledge that the

population of women has a lower hemoglobin value than does the population

of men.23

There is no stable and non-political place left. All variables-the individ-

ual, the category, the way of fitting into a category-may vary. The entity

that is given a sex also varies; it need not even be human. It may be an

institution, a word, a writing style, or an object. Take scientific concepts or

tools. Maybe statistics, hermeneutics, and semiotics are, indeed, &dquo;male

traditions.&dquo; Maybe it is worthwhile to ask for &dquo;female alternatives.&dquo; But

maybe one could also try to change his or her sex. Could the tools of

theoretical traditions be feminized one by one by being used differently?

Personally, I must admit, I often have a hard time telling whether a particular

argument, concept, or theory is &dquo;male&dquo; or not. But I do believe that the sex

of such entities is not inherent and that it can always be changed.24

There was a time when science was male business. No woman could be

expected to observe objectively.25 Later, method was said to be strong enough

to delete the subject making the observation, and sex was said to be irrelevant.

Science was neuter. However, feminists pointed out that the pictures accom-

panying such stories show mainly male faces. Behind the neutral facade, they

found science to be a male institution. What to do? It is possible to conclude

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

378

that science has to be made (more) female. One version of epistemology

argues that if more women become scientists and more feminine methods are

used, truth and objectivity would finally be attained?6

Constructivists, meanwhile, have made another move. They have said that

a scientist such as Pasteur did not use complicated arguments if people

disagreed with him. He simply said they had not done their washing up

properly!2 Thus they began to portray science more as ad hoc bricolage and

tinkering and less as grand theory and thinking. Science is not a matter of the

mind but is, first and foremost, a matter of the body, a mundane and material

matter, full of local idiosyncrasies and spontaneous moves. 28 In the great list

of dichotomies, all of these qualities belong to &dquo;women.&dquo; Nobody ever said

it in so many words, but in constructivism science is portrayed as a woman.

She: Something ironic is going on here, and I am not very sure whether our author

is keeping his or her neutrality-I mean, not that of an intersex, of course, but

of a constructivist-feminist hermaphrodite.

He: Yes. The rhetorical strategy is a bit dangerous. But it might be a good way to

draw the constructivists in.

She: How? By showing them that deep down they have been concerned about sex

all along?

He: Thats it. If you cant beat them, tell them they have joined you.

She: Boy, you are wicked.

He: Dont boy me!

She: So you do not like female power, do you? But we should not pretend we are

a tension-free zone, should we?

Intellectual Politics

Let me put together the two points I have made so far. For constructivism,

the topic of the sexes is a theoretical opportunity to turn from a persistent

anti-epistemological orientation to a fresh analysis of the frictions, reso-

nances, and alliances among sites and situations. And if feminism takes the

construction of the sexes more seriously, then empirical awareness of the

enormous variation of every dimension of sex will increase and new political

possibilities will emerge. One possibility would be altering the sex of science

by analyzing it as a mundane material practice.

But dont these suggestions conceal a bigger gap between feminism and

constructivism: the gap between doing politics and doing theory? Political

radicals often suspect theoretical radicals of political quietism. They use

&dquo;relativism&dquo; as a term of abuse, portraying relativists as failed political actors

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

379

and suggesting that those who have not failed can &dquo;reveal the truth&dquo; and

&dquo;change the world.&dquo; This suggestion presupposes that there is a place where

all knowledge might come together and from which effective, progressive

orders may be issued.

Talking about politics, I prefer to be more precise. I do not want to claim

too much. I have a traditional argument for this: there is, indeed, such a thing

as the specificity of tasks. The engagement of a politician, a transsexual, a

theorist, a writer of novels-all these differ. None may be outside politics,

but their political styles are not the same. Nor should one try to melt their

various merits into a single heroic figure, that of the &dquo;universal intellectual.&dquo;29

So if the feminist constructivism/constructivist feminism that I advocate

seems to take intellectual work rather far from what is relevant in everyday

life, I am not too worried. The drawback of exposing volatility in theory is

that it may leave the world as it is. But are revelations of the sadness of

everyday lives so much more revolutionary? It may very well be that one

contributes just as much to keeping the world the way it is by putting too

much &dquo;lived reality&dquo; into ones theories. There is a danger that critical

comments may be no more than a way of flagging values with which nobody

would think of disagreeing. All this does is reaffirm the place of morality in

this world as the constant companion of misery.

There is a gap between the politics of constructivism and feminism, but

there is a similarity, too. When it comes to interweaving political and

theoretical radicalism, feminist theory and constructivist studies of science

and technology share a common problem. Both risk getting stuck in mimick-

ing their objects. Like their objects, many &dquo;applied&dquo; science and technology

studies tell the truth or try to solve problems efficiently. They find facts, but

they love little and certainly never state their hatreds explicitly. They are

formal and accurate, not committed and passionate. Many feminist studies

of sex and gender suffer along with the women they go out to liberate. Their

theories are sad, reflecting the unpromising political situation of women-

and, quite unwillingly, thereby reinforcing it.

He: What I would like to mimic is the volatility of the objects. That you need not

be the same from one day to the next. That you may argue for one thing here

and now and for another later on or elsewhere.

She: What do you want? Good old liberal freedom to think? Or some fancy

postmodern version of it, like &dquo;being untrustworthy&dquo;?

He: I just wonder whether intellectuals should not insist more on their right to

change their minds continuously instead of raising the consciousness of others.

The right to be, lets say, &dquo;inauthentic.&dquo;

She: I will make you stick to that, then, shall I?

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

380

Constructivism risks becoming too formalistic, feminism too gloomy. I do

not doubt anyones political intentions, but I worry about their political

effects. Hybridization may be wise. When constructivism becomes con-

cerned, it holds a promise for feminism. When nothing is beyond construc-

tion, politics never hits on a boundary that says &dquo;do not enter, this is forbidden

terrain.&dquo; It never has to stop short on the fringes of a field that has been closed

off by scientific objectivity or the linear flow of passing time. Politics may

be tracked down everywhere. In other words, the political potential of

constructivism is that it may demonstrate quite radically the contingency of

our forms of life. So how could we, the writers of analytical texts, explore

this potential? How can the demonstration of contingency move beyond the

mere negation of facticity? How might we do contingency in writing? I have

some suggestions.

possibility is to write corrosive stories that do not submit to a

The first

theory by testing a hypothesis and do not submit to a policy by finding proof:

by performing the same pattern of dominance everywhere. Corrosive stories

do not try to make their readers change their minds by critical means.

Instead they try, by seduction, to alter their readers senses. They make

one see, hear, feel, and smell differently. What are the writing styles that

might have the sensual quality needed to do this? How might we get under

the readers skin?

It certainly will not be any good writing from a single standpoint or

&dquo;speaking for&dquo; the marginalized by carrying the moral weight of the suffering

of others. Instead of writing in a righteous way, it seems more promising to

try to articulate ambivalence, to address political sentiments not by loudly

advocating the truth in a single voice but by staging several voices of those

involved. And instead of having each of these affirm its standpoints, it

might be better to show what their questions are, what they think or worry

about. Texts about the multiple construction of the sexes may have

consequences only if they take risks. If they do not seek to control what

they achieve. Perhaps they will move the world only if they themselves are

also moving.

Finally, contingency can hardly be achieved if the status quo is confronted

with norms and values that come from outside. It seems wiser to try to dissect

selves and self-representations from the inside. Do not comment; interrupt.

Get into your objects, and become part of them. Go native, and do not worry

that it might take away your voice. You will be one voice among many; the

natives are divided among themselves. Come out and make something new.

Think of construction in a positive way. Do not be constructivist; be construc-

tive. Make! Make stories-with so many enemies, allies, and surprised

bystanders inscribed in them that they are strong enough to stand up when

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

381

you reintroduce them to the field you studied. They may then enhance this

fields own reflexivity. And change it.

Having dethroned epistemology, constructivists may take part in any

number of political fights. But constructivism may also develop its own

agenda(s) in a politics of knowledge. Which is what I have suggested here.

In mingling with the world, feminism needs a wide variety of strategies,

each one specific to its site and task. But in those places where a governing

knowledge needs to be contested and reshaped, it helps to be proudly

heretical, unstable, and of many sexes. It helps to move from one sex, one

identity, and one language to another.

Epilogue

She: Do you think we might still say something about language? About the fact

that we cannot write in German or Dutch and still be &dquo;international&dquo;? About

the imperialism implicated in that?

He: But that is a completely different political problem!

She: Are you sure? Let me confess that I find shifting from my own language into

English far more difficult than crossing the boundary between the sexes. And

the way this master language dominates us reminds me of the virtues of

old-fashioned theories that point at the patriarchal power of so-called male

institutions.

He: Oh, well, yes, sure. You are right. Language politics might hold some lessons

for feminists.

She: Heh, there you go again, man. Only thinking about yourself. Not only for

feminists, but for constructivists, too. You never seem to learn.

He: You are severe, very severe. Can I be the woman now for a while, please?

Notes

1. InEnglish, one has inevitably to choose between framing the difference between men

and women in a biological or a psychosocial way, between talking sex or talking gender (for a

twentieth-century history of this dichotomy, see Haraway 1991). As I make clear later, I do not

want to go along with this (for more extensive arguments, see Mol 1991 and Hirschauer 1993).

The German word Geschlecht and the Dutch word geslacht do not force me to choose. Because

the English language does, I go for the most disturbing option and write sex wherever I can.

2. For an attempt to make readers hurt in their private parts, see Hirschauer (1991).

3. One can presume that they have read this in Science in Action where Latour (1987, 33)

phrases it so beautifully: "A paper that does not have references is like a child without an escort

walking at night in a big city it does not know: isolated, lost, anything may happen to it."

4. The first version of this article had no footnotes. For one of the reviewers, this was a

reason to discard it: By not grounding the piece in the scholarly literature, it just does not meet

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

382

minimal standards of a journal article. Thus, as such, the piece becomes impossible to review

seriously."

5. Another reviewer, after all, wrote, "The authors cute decision to eschew references in

favor of a mere listing of literature (meaning that books and articles are detached from places

where their contents are used

) serves to heighten the appearance of originality."

6. Whereas constructivists seem to avoid having their unease printed, feminist criticisms

of gender blindness in science studies can be found, for instance, in Delamont (1987), Keller

(1988), Harding (1991), and Star (1992). For an affirmative version of selective relativism as

"having it both ways," see Harding (1993). For non-feminist intellectual strands criticizing

constructivism as being "elitist" or "unpolitical," see the debates in this journal between Lynch and

Fuhrmann (1991) and Lynch (1992), Winner (1993) and Elam (1994), and the essay of Martin

(1993)

7. At least it is for meteorologists and bisexuals. For the latter, see the life stories reported

in Wolff (1977). A good and early example of a study showing the shifts and layers in the

attribution of gender (in their case, to nature and culture) is Bloch and Bloch (1980).

8. For a more detailed description of these methods of sex determination, see Hirschauer

(forthcoming).

9. For an early version of the argument that the relations between these performances of

the sexes show such complexities, see Mol (1985).

10. For an extensive analysis of treatment programs for transsexuals, see Hirschauer (1993).

Also see Orobio de Castro (1993) and King (1993).

11. For an insightful history of the term patriarchy, tracing its articulation in nineteenth-

century Marxism, anthropology, and psychoanalysis and undermining its present-day feminist

value, see Coward (1983).

12. The constructivism of feminism differs greatly from one country to another. In the

Netherlands, for instance, feminists absorbed Foucault during the early 1980s. In Germany, they

hardly did and now are starting to embrace Butler. It seems as if, in Britain, psychoanalysis

survived better than did constructivism after the journal M/S stopped appearing. It would be

interesting to compare these different patterns of feminist sensitivity to constructivism with the

sensitivities to feminism in circles of science and technology studies in different countries.

13. This is an allusion, indeed, to De Beauvoir (1949).

14. I am elaborating here the notion of sex as an ongoing accomplishment that was introduced

by Garfinkel (1967). A late, postmodern echo of this position is Butler (1990).

15. Admittedly, I go a bit fast here. For more extended and subtle versions, see the

contributions to Harding and Hintikka (1983); for a more recent position, see Harding (1991);

and, regarding technology, see Cockburn (1985).

16. A good example of a non-individualistic perspective on homosocial epistemic cultures

is Shapins (1988) analysis of the rooting of knowledge claims in the conventions regulating

relations among "gentlemen" m seventeenth-century England.

17. The relationship between contingency and stability of the construction of two sexes—that

is, the relation between "undoing gender" and the institutional reproduction of the difference—is

tackled in Hirschauer (1994).

18. On the topic of material instability, see also Law and Mol (forthcoming).

19 For the use of the metaphor of the Berlin Wall as a symbol of boundaries that seemed

solid and yet melted, see Latour (1992).

20. For one of the versions of this history, see Laqueur (1990). For a slightly different

histoncal account, see Jordanova (1989)

21. A more extensive version of this history is presented in Hirschauer (1993, 69 ff.).

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

383

22. Some of the various ways in which anemia may be performed and the complicated

relations between them are discussed in Mol and Berg (1994).

23. Some preprinted lab forms make it more complicated. They first separate out children,

without sex. And for adults, they have three boxes or categories in which a doctor may put a

cross: men, women, pregnants.

24. I agree with Hawkesworth (1989), who recommends that feminism, instead of criticizing

the masculine character of intellectual traditions, should actively use and change the multiple

and always contested traditions for its own purpose.

25. There are several good books documenting this history (see, e.g., Schiebinger 1989).

26. This position not only essentializes gender as a trait of scientists but, moreover,

essentializes "method" as a core of science (see Richards and Schuster 1989). Hardings (1993)

"Mertonian" suggestion to understand traditional objectivity of science in terms of moral values

such as fairness, honesty, and detachment is another version of this essentialism.

27. The example is from Latour (1984).

28. See Knorr-Cetina (1981).

29. As Foucault (1977) has called this hero; he was asked and yet refused to be.

References

Bloch, Maurice, and Jean Bloch. 1980. Women and the dialectics of nature. In Nature, culture

and gender, edited by C. MacCormack and M. Strathern, pp. 25-41. Cambridge, England:

Cambridge University Press.

Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. London:

Routledge.

Cockburn, Cynthia. 1985. Machinery of dominance: Women, men and technical know-how.

Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Coward, Rosalind. 1983. Patriarchal precedents: Sexuality and social relations. London:

Routledge & Kegan Paul.

De Beauvoir, Simone. 1949. La deuxième sexe. Paris: Gallimard.

Delamont, Sara. 1987. Three blind spots? A comment on the sociology of science by a puzzled

outsider. Social Studies of Science 17:163-70.

Elam, Mark. 1994. Anti anticonstructivism or laying the fears of a Langdon Winner to rest.

Science, Technology & Human Values 19:101-6.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. Language, counter-memory, practice: Selected essays and interviews.

Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell.

Garfinkel, Harold. 1967. Passing and the managed achievement of sex status in an "intersexed"

person. In Studies in ethnomethodology, pp. 116-85. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Haraway, Donna. 1991. Simians, cyborgs, and women: The reinvention of nature. London: Free

Association Books.

Harding, Sandra. 1991. Whose science? Whose knowledge? Milton Keynes, England: Open

University Press.

—. 1993. Rethinking standpoint epistemology: What is "strong objectivity"? In Feminist

epistemologies, edited by L. Alcoff and E. Potter. London: Routledge.

Harding, Sandra, and Merrill Hintikka, eds. 1983. Discovering reality: Feminist perspectives on

epistemology, metaphysics, methodology and philosophy . of science Dordrecht, Netherlands

Kluwer.

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

384

Hawkesworth, Mary. 1989. Knowers, knowing, and known: Feminist theories and claims of

truth. Signs 14:533-57.

Hirschauer, Stefan. 1991. The manufacture of bodies in surgery. Social Studies of Science

21:279-319.

—. 1993. Die soziale Konstruktion der Transsexualitat. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

—. 1994. Die soziale

Fortpflanzung der Zweigeschlechtlichkeit. Kolner Zeitschrift fur

Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 46:667-91.

-.

Forthcoming. Doing sex and doing gender in medical disciplines. In Differences in

medicine, edited by M. Berg and A. Mol.

Jordanova, Ludmilla. 1989. Sexual visions. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Keller, Evelyn Fox. 1988. Feminist perspectives on science studies. Science, Technology, &

Human Values 13:235-49.

King, Dave. 1993. The transvestite and the transsexual: A case study of public categories and

private identities. Avebury, U.K. Ashgate.

Knorr-Cetina, Karin. 1981. The manufacture of knowledge. Oxford, England: Pergamon.

Laqueur, Thomas. 1990. Making sex: Body and gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge,

MA: Harvard University Press.

Latour, Bruno. 1984. Les microbes. Paris: Métailié.

—. 1987. Science in action. London: Open University Press.

—. 1992. Nous navons jamais été modernes. Paris: Editions de la Découverte.

Law, John, and Annemarie Mol. Forthcoming. Notes on materiality and sociality. Sociological

Review.

Lynch, Michael. 1992. Going full circle in the sociology of knowledge. Science, Technology, &

Human Values 17:228-33.

Lynch, William, and Ellsworth Fuhrmann.1991. Recovering and expanding the normative: Marx

and the new sociology of scientific knowledge. Science, Technology, & Human Values

16:233-48.

Martin, Brian. 1993. The critique of science becomes academic. Science, Technology, & Human

Values 18:247-59.

Martin, Emily. 1994. Flexible bodies: Tracking immunity in American culture: From the days

of polio to the age .

of AIDS Boston: Beacon.

Mol, Annemane. 1985. Wie weet wat een vrouw is ... Over de verschillen en de verhoudingen

tussen de wetenschappen. Tijdschrift voor Vrouwenstudies 21:10-22.

-. 1991. Wombs, pigmentation and pyramids: Should antiracists and feminists try to

confine "biology" to its proper place? In Sharing the difference, edited by A. van Lenning

and J. Hermsen, 149-63. London: Routledge.

Mol, Annemarie, and Marc Berg. 1994. Principles and practices of medicine: The co-existence

of various anemias. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 18:247-65.

Orobio de Castro, Ines. 1993. Made to order: Sex/gender in a transsexual perspective. Amster-

dam : Het Spinhuis.

Richards, Evelleen, and John Schuster. 1989. The feminine method as myth and accounting

resource Social Studies of Science 19:697-720.

Schiebinger, Londa. 1989 The mind has no sex? Women in the ongins of modern science.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shapin, Steven. 1988. The house of experiment in seventeenth-century England. Isis 79:373-404.

Star, Susan Leigh. 1992. Power, technology and the phenomenology of conventions: On being

allergic to onions In A sociology of monsters, edited by John Law, pp. 26-56. London:

Routledge.

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

385

Winner, Langdon.1993. Upon opening the black box and finding it empty. Scrence, Technology, &

Human Values 18:362-78.

Wolff, Charlotte. 1977. Bisexuality: A study. London: Quartet Books.

Stefan Hirschauer is a Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Bielefelt4 Germany

(PO. 100131, D-33501 Bielefeld). His research focuses on the social construction of sex

and gender He has recently published Die soziale Konstruktion der Transsexualitat [The

Social Construction of Transsexuality7 (Frankfurt, 1993). He is currently engaged m a

study on prenatal sex determination by mothers, midwives, and doctors.

Annemarie Mol is a Constantijn and Christiaan Huygens Fellow of the Netherlands

Organization for Scientific Research. She is affiliated with the Department of Philosophy

of the University of Limburg (P.O. 1600, 6200 MD Maastricht, Netherlands) and the

Department of Internal Medicine of the University of Utrecht. Her research focuses on

the co-existence of different ontologies and normative logics within Western medicine.

Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on March 15,

2015

Você também pode gostar

- Someone: The Pragmatics of Misfit Sexualities, from Colette to Hervé GuibertNo EverandSomeone: The Pragmatics of Misfit Sexualities, from Colette to Hervé GuibertAinda não há avaliações

- Interview With Judith Butler To Sara Ahm PDFDocumento11 páginasInterview With Judith Butler To Sara Ahm PDFEnzo Antonio Isola SanchezAinda não há avaliações

- Dicta Torship: DPI Page 1Documento28 páginasDicta Torship: DPI Page 1Max FoxAinda não há avaliações

- What Do You Want Out of Life?: A Philosophical Guide to Figuring Out What MattersNo EverandWhat Do You Want Out of Life?: A Philosophical Guide to Figuring Out What MattersAinda não há avaliações

- Your Vagina Is A Bigot My PDFDocumento37 páginasYour Vagina Is A Bigot My PDFAnonymous 7Yf2Muq4Ca100% (1)

- Research Paper On Bell HooksDocumento4 páginasResearch Paper On Bell Hookskbcymacnd100% (1)

- Transcending Racial Divisions: Will You Stand By Me?No EverandTranscending Racial Divisions: Will You Stand By Me?Ainda não há avaliações

- Feminism & Psychology: I. Breaking Down Barriers: Feminism, Politics and PsychologyDocumento6 páginasFeminism & Psychology: I. Breaking Down Barriers: Feminism, Politics and PsychologyPsicología Educativa LUZ-COLAinda não há avaliações

- Figures of the One Must Go: Symbolical Logo-roots Book One, #1No EverandFigures of the One Must Go: Symbolical Logo-roots Book One, #1Ainda não há avaliações

- Interview With Judith ButlerDocumento11 páginasInterview With Judith ButlerNickPanAinda não há avaliações

- I. Learning Skills: Senior High School: 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The WorldDocumento7 páginasI. Learning Skills: Senior High School: 21 Century Literature From The Philippines and The Worldkarizajean desalisaAinda não há avaliações

- Women: Body-Positive Art to Inspire and EmpowerNo EverandWomen: Body-Positive Art to Inspire and EmpowerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (14)

- 新建 DOC 文档Documento6 páginas新建 DOC 文档Jianquan ZhangAinda não há avaliações

- Response Paper ExamplesDocumento4 páginasResponse Paper ExamplesBobbyNicholsAinda não há avaliações

- Invitation to Sociology: A Humanistic PerspectiveNo EverandInvitation to Sociology: A Humanistic PerspectiveNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (50)

- Women and Status in PhilosophyDocumento3 páginasWomen and Status in PhilosophyBabette BabichAinda não há avaliações

- What Happened to College? How University Turned Our Daughter into a Social Justice WarriorNo EverandWhat Happened to College? How University Turned Our Daughter into a Social Justice WarriorNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- High School Essays SamplesDocumento7 páginasHigh School Essays Samplesezmsdedp100% (1)

- It’S Not Always Racist … but Sometimes It Is: Reshaping How We Think About RacismNo EverandIt’S Not Always Racist … but Sometimes It Is: Reshaping How We Think About RacismAinda não há avaliações

- Gayatri Chakravorty SpivakDocumento9 páginasGayatri Chakravorty SpivakDjordjeAinda não há avaliações

- The Letter F:: The Process of Civilly Changing SexNo EverandThe Letter F:: The Process of Civilly Changing SexAinda não há avaliações

- Haslanger. 2000. Geder and Race - What Are TheyDocumento26 páginasHaslanger. 2000. Geder and Race - What Are TheyakupaAinda não há avaliações

- You Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in ConversationNo EverandYou Just Don't Understand: Women and Men in ConversationNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (20)

- Alice Dreger - Can We Have Sex BackDocumento5 páginasAlice Dreger - Can We Have Sex BackdpolsekAinda não há avaliações

- I Myself Have Never Been Able To Find Out Precisely What Feminism IsDocumento3 páginasI Myself Have Never Been Able To Find Out Precisely What Feminism IsHemaAinda não há avaliações

- Breaking The ManaclesDocumento20 páginasBreaking The ManaclesbmazzottiAinda não há avaliações

- Atubes: Digest Ofthe Anarchist TubesDocumento8 páginasAtubes: Digest Ofthe Anarchist TubesPau Osuna PolainaAinda não há avaliações

- Analisis Sobre Feminist Perspectives On Sex and GenderDocumento9 páginasAnalisis Sobre Feminist Perspectives On Sex and GenderValeriaMorenoAinda não há avaliações

- Stereotype Essay ExamplesDocumento6 páginasStereotype Essay Examplesd3gn731z100% (2)

- Mckayta-Nehisi Coates AnalysisDocumento4 páginasMckayta-Nehisi Coates Analysisapi-572228483Ainda não há avaliações

- The Giver Essay QuestionsDocumento6 páginasThe Giver Essay Questionsxlfbsuwhd100% (2)

- Poem Analysis Essay ExampleDocumento8 páginasPoem Analysis Essay Examplefz67946y100% (2)

- Zona Muda de Al RSDocumento10 páginasZona Muda de Al RSMafaldo KynAinda não há avaliações

- Gender and Race: (What) Are They? (What) Do We Want Them To Be?Documento25 páginasGender and Race: (What) Are They? (What) Do We Want Them To Be?156majamaAinda não há avaliações

- EnglishDocumento8 páginasEnglishKikuko KatoAinda não há avaliações

- Raewyn ConnellDocumento3 páginasRaewyn ConnellMariacon1Ainda não há avaliações

- Women Love Sexist MenDocumento15 páginasWomen Love Sexist Menaran singhAinda não há avaliações

- Types EssayDocumento4 páginasTypes Essaysmgcjvwhd100% (2)

- English SBADocumento19 páginasEnglish SBARenay CampbellAinda não há avaliações

- How To Write A Good Essay About YourselfDocumento3 páginasHow To Write A Good Essay About Yourselfppggihnbf100% (2)

- The Metaphysics Behind Discrimination - PagesDocumento60 páginasThe Metaphysics Behind Discrimination - PagesAle TeruelAinda não há avaliações

- wp2 Messy FinalDocumento5 páginaswp2 Messy Finalapi-490540121Ainda não há avaliações

- Lit Circle Notes: Introduction: Group MembersDocumento9 páginasLit Circle Notes: Introduction: Group MembersdjelifAinda não há avaliações

- Lit Reviewer FinalDocumento62 páginasLit Reviewer FinalJanelle Alyson De GuzmanAinda não há avaliações

- Gage Rhetorical VirtueDocumento9 páginasGage Rhetorical Virtuerws_sdsuAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis For Do The Right ThingDocumento7 páginasThesis For Do The Right Thingfjgh25f8100% (2)

- Antigone EssayDocumento9 páginasAntigone Essaybmakkoaeg100% (2)

- Literature.: Literary Analysis Means Closely Studying A Text, Interpreting Its Meanings, and Exploring Why TheDocumento4 páginasLiterature.: Literary Analysis Means Closely Studying A Text, Interpreting Its Meanings, and Exploring Why Theglicer gacayanAinda não há avaliações

- 2021 Language Analysis Reporting StructuresDocumento5 páginas2021 Language Analysis Reporting StructuresPaulina CaillatAinda não há avaliações

- "We Are The People Who Do Not Count": Thinking The Disruption of The Biopolitics of AbandonmentDocumento232 páginas"We Are The People Who Do Not Count": Thinking The Disruption of The Biopolitics of AbandonmentTigersEye99Ainda não há avaliações

- A Letter On A LetterDocumento43 páginasA Letter On A LetterPeter DerkAinda não há avaliações

- Mahdzar, S.S.B.S. (2008) Sociability Vs Accessibility Urban Street Life. Doctoral Thesis, University of London.Documento434 páginasMahdzar, S.S.B.S. (2008) Sociability Vs Accessibility Urban Street Life. Doctoral Thesis, University of London.yoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- NAWROCKI, T. Mental MapsDocumento13 páginasNAWROCKI, T. Mental MapsyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Dialogic Action For Critical Democracy: Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USADocumento25 páginasDialogic Action For Critical Democracy: Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USAyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- The Power of Human Rights PDFDocumento74 páginasThe Power of Human Rights PDFyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Manisha Desai 2016Documento15 páginasManisha Desai 2016yoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Pedagogies of Resistance and Critical Pedagogy PDFDocumento13 páginasPedagogies of Resistance and Critical Pedagogy PDFyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Weiker1968 Tanzimat ReformsDocumento21 páginasWeiker1968 Tanzimat ReformsyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Davies2013 Human Rights Constructivism Rational ChoiceDocumento25 páginasDavies2013 Human Rights Constructivism Rational ChoiceyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Badran 1988 Dual Liberation. Feminism and Nationalism in EgyptDocumento20 páginasBadran 1988 Dual Liberation. Feminism and Nationalism in EgyptyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Martha Finnemore Norms Culture and World Politics: Insights From Sociology's InstitutionalismDocumento24 páginasMartha Finnemore Norms Culture and World Politics: Insights From Sociology's InstitutionalismyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Youngs2004 FEMINIST INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS OR WHY WOMEN AND GENDER ARE ESSENTIAL TO UNDERSTANDING PDFDocumento13 páginasYoungs2004 FEMINIST INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS OR WHY WOMEN AND GENDER ARE ESSENTIAL TO UNDERSTANDING PDFyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Roland Axtman 2004 The State of The StateDocumento22 páginasRoland Axtman 2004 The State of The StateyoginireaderAinda não há avaliações

- Ars Magica - Virtues and Flaws - Master List PDFDocumento25 páginasArs Magica - Virtues and Flaws - Master List PDFwroueawe33% (3)

- Indian Insights - Buddhism, Brahmanism and BhaktiDocumento231 páginasIndian Insights - Buddhism, Brahmanism and BhaktiGuhyaprajñāmitra3100% (1)

- MysticismDocumento397 páginasMysticismayu7kaji100% (1)

- CRYptwordlDocumento2 páginasCRYptwordlXKkZHzZZrPd6lp1aAinda não há avaliações

- Grimoire of Atlantean TeachingsDocumento21 páginasGrimoire of Atlantean TeachingsTe Ariki100% (2)

- Signs Out of Time - TranscriptDocumento19 páginasSigns Out of Time - TranscriptVeronikaAinda não há avaliações

- BA 4 Yrs Anthro Major Syllabus First YearDocumento8 páginasBA 4 Yrs Anthro Major Syllabus First YearUchiha TObiAinda não há avaliações

- Wp1-Final Draft 1Documento5 páginasWp1-Final Draft 1api-514806715Ainda não há avaliações

- Damon Self UnderstandingDocumento21 páginasDamon Self UnderstandingRamani ChandranAinda não há avaliações

- Fran Markowitz Sarajevo A Bosnian Kaleidoscope Interp Culture New Millennium 2010 PDFDocumento118 páginasFran Markowitz Sarajevo A Bosnian Kaleidoscope Interp Culture New Millennium 2010 PDFMahir HrnjićAinda não há avaliações

- Global English Teaching PronunciationDocumento2 páginasGlobal English Teaching PronunciationSu HandokoAinda não há avaliações

- A Practical Guide To Witchcraft and Magic Spells by Cassandra EasonDocumento268 páginasA Practical Guide To Witchcraft and Magic Spells by Cassandra Easonvarkie23Ainda não há avaliações

- Rock Art AnatoliaDocumento18 páginasRock Art AnatoliaBeste AksoyAinda não há avaliações

- Walter Odajnyk - Jung and PoliticsDocumento106 páginasWalter Odajnyk - Jung and PoliticsKatia VoigtAinda não há avaliações

- Spiritism in BrazilDocumento17 páginasSpiritism in BrazilEugene EdoAinda não há avaliações

- Contoh Dialog NarrativeDocumento3 páginasContoh Dialog NarrativemarkonahencuyAinda não há avaliações

- The Sacred Seven PDFDocumento39 páginasThe Sacred Seven PDFNubyh Stone67% (3)

- (Bioarchaeology and Social Theory) Pamela K. Stone (Eds.)- Bioarchaeological Analyses and Bodies_ New Ways of Knowing Anatomical and Archaeological Skeletal Collections-Springer International PublishiDocumento253 páginas(Bioarchaeology and Social Theory) Pamela K. Stone (Eds.)- Bioarchaeological Analyses and Bodies_ New Ways of Knowing Anatomical and Archaeological Skeletal Collections-Springer International PublishiAcceso Libre100% (2)

- Merriam Anthropology Music Chapter 1Documento10 páginasMerriam Anthropology Music Chapter 1PaccorieAinda não há avaliações

- Interview John SwalesDocumento6 páginasInterview John SwalesIrineu CruzeiroAinda não há avaliações

- Hammer and KlaiveDocumento128 páginasHammer and KlaiveEric Pridgen100% (12)

- Buddhist ProphecyDocumento14 páginasBuddhist ProphecyBenny BennyAinda não há avaliações

- Notes For A History of Peruvian Social AnthropologyDocumento19 páginasNotes For A History of Peruvian Social AnthropologyKaren BenezraAinda não há avaliações

- Between Chaos and Cosmos - Ernesto Grassi, William Faulkner and The Compulsion To SpeakDocumento24 páginasBetween Chaos and Cosmos - Ernesto Grassi, William Faulkner and The Compulsion To SpeakposthocAinda não há avaliações

- 1-End of Anthropology. J ComaroffDocumento16 páginas1-End of Anthropology. J ComaroffBrad WeissAinda não há avaliações

- DocumentDocumento9 páginasDocumentchris iyaAinda não há avaliações

- Tsing 1994 From The MarginsDocumento20 páginasTsing 1994 From The MarginsJoel StockerAinda não há avaliações

- Jak Narody Porozumiewają Się Ze Sobą W Komunikacji Międzykulturowej I Komunikowaniu MedialnymDocumento13 páginasJak Narody Porozumiewają Się Ze Sobą W Komunikacji Międzykulturowej I Komunikowaniu MedialnymkusumAinda não há avaliações

- Exorcism of The Crown of AnuDocumento3 páginasExorcism of The Crown of AnuAmadi PierreAinda não há avaliações

- D&D Next Spellbook Card GeneratorDocumento24 páginasD&D Next Spellbook Card GeneratorRobert ScottAinda não há avaliações

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsNo EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (16)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryNo EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (14)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsNo EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (387)

- Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityNo EverandGender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (317)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateNo EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (18)

- Lucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindNo EverandLucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (54)

- Feminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionNo EverandFeminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (89)

- Crones Don't Whine: Concentrated Wisdom for Juicy WomenNo EverandCrones Don't Whine: Concentrated Wisdom for Juicy WomenNota: 2.5 de 5 estrelas2.5/5 (3)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsNo EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (1424)

- Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureNo EverandAbolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (4)

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusNo EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (22)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamNo EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamAinda não há avaliações

- Period Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working For YouNo EverandPeriod Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working For YouNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (25)

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveNo EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (22)

- Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too MovementNo EverandUnbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too MovementNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (147)

- The Souls of Black Folk: Original Classic EditionNo EverandThe Souls of Black Folk: Original Classic EditionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (441)

- Becoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our FutureNo EverandBecoming Kin: An Indigenous Call to Unforgetting the Past and Reimagining Our FutureNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (10)

- For the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityNo EverandFor the Love of Men: From Toxic to a More Mindful MasculinityNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (56)

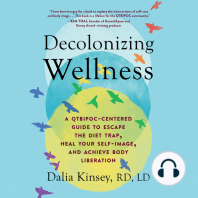

- Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationNo EverandDecolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (22)

- Tears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalNo EverandTears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (136)