Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Wacquant 2003 Ethnografeast. Ethnog 4

Enviado por

Luis Covarrubias GutierrezTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Wacquant 2003 Ethnografeast. Ethnog 4

Enviado por

Luis Covarrubias GutierrezDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Ethnography

http://eth.sagepub.com/

Ethnografeast : A Progress Report on the Practice and Promise of

Ethnography

Loc Wacquant

Ethnography 2003 4: 5

DOI: 10.1177/1466138103004001001

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://eth.sagepub.com/content/4/1/5

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Ethnography can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://eth.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://eth.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://eth.sagepub.com/content/4/1/5.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Mar 1, 2003

What is This?

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 5

graphy

Copyright 2003 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi)

www.sagepublications.com Vol 4(1): 514[14661381(200303)4:1;514;035380]

Ethnografeast

A progress report on the practice and promise of

ethnography

Loc Wacquant

University of California-Berkeley, USA

Centre de sociologie europenne, Paris, France

On 1214 September 2002, the journal Ethnography and the Center for

Urban Ethnography at the University of California, Berkeley, held an inter-

national conference on Ethnography for a New Century: Practice, Predica-

ment, Promise.1 The purpose of the three-day event was to take collective

stock of the past achievements, to reflect on the contemporary practice, and

to sketch the future promise of ethnography as a distinctive mode of inquiry

and form of public consciousness. For that purpose, ethnography was

defined, in catholic fashion, as social research based on the close-up, on-

the-ground observation of people and institutions in real time and space, in

which the investigator embeds herself near (or within) the phenomenon so

as to detect how and why agents on the scene act, think and feel the way

they do. Drawing on and projecting forth from their own fieldwork

spanning the gamut of topics and styles, the participants were invited to

examine the epistemological moorings, methodological quandaries, repre-

sentational devices, empirical and theoretical (im)possibilities, as well as the

changing politics and ethics of ethnography at centurys dawn. And in the

process to illumine its relation to and its uses of fiction, philosophy,

medicine, statistics, political economy, feminism, history, and theory in fast-

changing academic worlds and societal landscapes.

The spirit of the conference was one of open and attentive dialogue

across three divides that, although widely recognized as arbitrary, continue

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 6

6 E t h n o g r a p h y 4(1)

to impede the development of field-based social inquiry as they do research

based on other methodologies. The first is the continuing split between

national traditions, and the mutual ignorance and symbolic imperialism it

fosters (Gupta and Ferguson, 1997: 2529), which was lessened by conven-

ing scholars coming not only from the four corners of the United States but

also from London, Stockholm, Paris, So Paulo, and Cape Town. The

second is the separation of disciplines: the main impulse behind the

conference was to get a group of anthropologists and sociologists who seri-

ously practice and think about fieldwork to come not face to face but side

by side; to suspend lingering disdain, distrust and doubt, and to remove

their professional blinders so as to get each to acknowledge and engage the

varied approaches and productions of their twin colleagues in a way that

was routinely done a century ago by the Durkheimians (as attested by

Mauss, 1913) but that, for reasons having to do with the accumulated acci-

dents of academic and political history, is rarely done in earnest today.2

Needless to say, numerous other disciplines are concerned by the concep-

tual and practical issues on which the conference fastened: the remarkable

renewal and growth of ethnography over the past decade has touched an

unprecedented variety of knowledge domains ranging from education, law,

media and science studies to geography, history, management and design, to

gender studies and nursing.3 Far from being an extinct or endangered species,

as the prophets of postmodern gloom would have us believe, ethnography is

a proliferating animal that walks on multiplying feet. But, for reasons having

to do with its intellectual history and institutional ecology, its two main legs

remain anthropology and sociology (Stacey, 1999). Indeed, the premise and

wager of the Ethnografeast was that the most promising route for strength-

ening and enriching the craft of field inquiry at this particular juncture lies

not in grand theoretical elaborations, worried epistemological disquisitions,

or deliberate rhetorical innovations (however important these may be in their

own right, and they are) but in the long overdue, systematic and self-

conscious braiding of actually existing traditions of fieldwork across that

artificial disciplinary divide as anthropologists return home and sociologists

go global (Peirano, 1998 and Gille and Riain, 2002).

Third, and by design, the conference brought together the diversity of

styles of ethnographic work modern, neomodern, and postmodern; posi-

tivist, interpretive and analytic; phenomenological, interactionist and

historical; theory-driven and narrative-oriented; local, multi-sited, and

global 4 as conduced by authors who draw on the broadest array of

theoretical traditions in the social sciences, from Marx and Merleau-Ponty

to Bourdieu and Blumer to Goffman and Geertz, and seek to amplify or

rectify intellectual currents as varied as the Chicago school, feminism(s),

identity politics, organization theory, and postcolonialism. This threefold

commitment to internationalism, interdisciplinarity rooted in a vigorous

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 7

Wacquant Ethnografeast 7

and rigorous dialogue between sociology and anthropology, and pluralism

in genres and theoretical suasions is epicentral to the mission of Ethnogra-

phy. It sets the editorial policy and defines the distinctive intellectual stance

of the journal in the ever-more cluttered space of social scientific produc-

tion. And it will continue to guide its efforts to stimulate and disseminate

innovative fieldwork stamped by theoretical sensitivity, empirical commit-

ment, and civic relevance.

The Ethnografeast started off with a session titled Suspended Between

Theory and Fiction, in which sociologist Michael Boris Burawoy presented

the case for theory-driven ethnography carried out under the banner of

science while anthropologist Ruth Behar advocated a humanistic approach

based on story-telling closer to writing and film. The BeharBurawoy

pairing was meant to incarnate the two poles of the craft, that of expla-

nation and interpretation, experiment and narration, observer concept and

native percept, and to invite each to recognize, exchange with, and learn

from the other. Sessions held on the ensuing two days addressed violence,

social divisions and bonds (kinship, class, and gender), the ethics of field-

work, and the body and the senses, before returning to the role of history

and theory in ethnography. Presentations were based on completed or

ongoing research into subjects as variegated as drug addiction in San Fran-

cisco and crime in So Paulo, the politics of medicine in Haiti and the

aesthetics of death in Nepal, sentiments in French families and gender in

Mexican factories, morality among American physicians and zombies in

post-apartheid South Africa, and the occupational habits of school adminis-

trators, mushroom collectors, urban planners, professional boxers, inter-

national journalists, and global organs traffickers.

The conference opened on a double dedication, the one joyful and the

other somber. The first was to Michael Boris Burawoy, who received a

special award in recognition of 25 years devoted to teaching, practicing, and

promoting ethnography at Berkeley. So much so that one could argue that

he has single-handedly created a Berkeley school of field research, with

roots in Manchester by way of Lusaka, Chicago, Budapest and Syktyvkar

in Northern Russia, mating the extended case method of Jaan van Velsen

and Max Gluckman to the theoretical agenda of an epistemologically astute

and empirically aware Marxism scouring the globe in stubborn search for

the politics of production (Burawoy, 1998 and 2000a). Bridging the gap

between anthropology and sociology, as well as between theory and

method, Burawoy has not only produced classic field studies of labor

and working class (de)formation under capitalist evolution and Soviet in-

volution (see Burawoy, 1996, for a reflexive recapitulation). He has trained

cohorts of first-rate ethnographers who have gone on from being

close collaborators in a revolving ethnographic cooperative (Burawoy et

al., 1991; Burawoy et al., 2000) to influential authors with their own agenda

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 8

8 E t h n o g r a p h y 4(1)

and voice and working at the four corners of the earth. And, whether one

admires or deplores his obdurate insistence on the centrality of class and

capitalism, Burawoy has time and again demonstrated the scientific and

political pertinence of field inquiry to the ongoing great transformations

of our epoch, thus setting high standards for an ethnography alive to its

civic responsibility.5

The second dedication was to Pierre Bourdieu, who agreed, in summer of

2001, to come to Berkeley for the Ethnografeast and to deliver a closing

address on Ethnography as Public Service. His sudden and untimely passing

in January 2002 not only robs the social sciences and humanities of one of

their most innovative and influential practicioners. It deprives activists fighting

for social justice around the world of an engaged intellectual who was deeply

committed to making the results of social inquiry inform and impact demo-

cratic struggles. And it leaves many of us bereft of an irreplaceable friend and

wonderful human being. Pierre Bourdieu was an inventive and iconoclastic

scientist who transformed social science by fusing rigorous theory with precise

research, including ethnography, which he taught himself in the late 1950s

crisscrossing the countryside and delving into the urban slums of colonial

Algeria in the grisly conditions of the war of national liberation.6

In the introduction to his 1963 book Travail et travailleurs en Algrie,

his first methodological notations, Bourdieu called for a forthright

collaboration between statistics and sociology, by which he meant inten-

sive field studies that are alone capable of ferreting out the social meaning

that patterns of action and belief acquire in the concrete cases that quan-

titative techniques parse, aggregate and correlate (Bourdieu et al., 1963:

913). And he dutifully followed his own prescription: Bourdieu resorted

to detailed and sustained in situ observation in every one of his major

studies thereafter, from the dissection of gender relations and kinship

strategies in his native village of Barn to the analysis of taste in the making

of class and of the rituals of consecration of the state nobility to the diag-

nosis of novel forms social suffering in societies wracked by economic

deregulation and welfare-state devolution (Bourdieu, 2002; 1979[1984];

1989[1996]; Bourdieu et al., 1993[1997]). Bourdieu was the first scholar

to truly reunify sociology and anthropology in his practice since the

classical generation in which his work was anchored and the Ethno-

grafeast was a means to acknowledge and advance on the path he cleared.

In lieu of a tribute or homage (something he profoundly disliked: he once

quipped hommage gale fromage), the conference included an evening

with Pierre Bourdieu in the form of the official U.S. premiere of the award-

winning documentary on his life and thought, Sociology is a Martial Art

by Pierre Carles (2001).7

By convening this gathering of anthropologists and sociologists com-

mitted to the craft, Ethnography sought to provoke a confrontation of

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 9

Wacquant Ethnografeast 9

experiences, purposes, and views liable to clarify its standards and to make

the case for the renewed vigor and centrality of ethnography to social

research, as well as for its pertinence to social policy and citizenship after a

protracted period of solipsistic doubt and nihilistic rumination. If anything,

the three days of lively debates before a packed room and the subsequent

exchanges they triggered through manifold media offered irrefutable proof

that reports of the death of ethnography have been wildly exaggerated

they turn out to be little more than the prescriptive cries of those who, having

stopped doing fieldwork, need to make an epistemological virtue out of their

professional surrender. They confirmed that field inquiry is a diverse enter-

prise admitting of a variety of standards of production and evaluation but

one endowed with a strong core of common epistemological and operational

principles readily apparent in its finished products.8 And they made it clear

that the balance sheet of similarities and differences between sociologists and

anthropologists active in the field tilts decisively in favor of the former:

indeed, there was more dispersion of style, focus and concern within each of

the disciplines than between them. What separates sociologists and

anthropologists are the ready-made problematics they inherit, the universe

of references and studies they build on, and the idiom in which they articu-

late their questions, as a result of the separate training they receive and the

distinct career tracks they follow. Shed this professional garb (or armor) and

they turn out to be not sister disciplines but identical twins.

The three papers by Ruth Behar, Mary Pattillo, and Gary Fine featured

in this issue form the first of several installments of contributions to the

Ethnografeast. It is hoped that publication of these presentations will help

extend and enlarge the animated discussion of the distinctive problems and

promise of ethnography that took place in Berkeley. (Ethnography

welcomes reactions and commentaries that take up central issues addressed

or evaded by several papers). And that it will feed intellectual exchanges

across disciplinary boundaries liable to erode the arbitrary mental and

professional divisions that hamper the full blossoming of an ethnographic

social science.

Appendix: Summary Program of the Ethnografeast

Day 1 Thursday 12 September 2002

1 Suspended between theory and fiction

Ruth Behar (University of Michigan): Adio Kerida: Ethnography without

Borders

Michael Burawoy (University of CaliforniaBerkeley): Standing on the

Shoulders of Giants: Bringing Theory and History to Ethnography

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 10

10 E t h n o g r a p h y 4(1)

811pm, Wheeler Auditorium: An evening with Pierre Bourdieu USA

Premiere of Pierre Carles Sociology is a Martial Art, introduced by

Chancellor Robert Berdahl and followed by a debate with director Pierre

Carles and Linda Williams (Chair of UCBerkeley Film Studies).

Day 2 Friday 13 September 2002

2 Dissecting violence

Philippe Bourgois and Jeff Schonberg (University of CaliforniaSan Fran-

cisco): Heroin, Crack and Homelessness in Black and White: A Photo-

Ethnography from San Francisco

Martn Snchez-Jankowski (University of CaliforniaBerkeley): The Role

of School Violence in Leveling Aspirations and Curtailing Mobility among

the Poor in Two American Cities

Teresa Caldeira (Universidade So Paulo, University of CaliforniaIrvine):

Crime and Rights in Contemporary Brazil

Paul Farmer (Harvard University): Toward an Ethnography of Structural

Violence: Haiti and Beyond

3 Bonds and divisions: kinship, gender, class

Florence Weber (Ecole normale suprieureParis): Sentiments, Strategies

and Models in the Ethnography of Kinship and Kin Dependency

Leslie Salzinger (University of Chicago): Now You See It, Now You Dont:

Masculinity at Work

Sherry Ortner (Columbia University): New Jersey Dreaming: Theoretical

Intentions and Field Lessons of a Native Ethnographer

Discussant: Raka Ray (University of CaliforniaBerkeley)

4 The contested politics and ethics of field work

Mary Pattillo (Northwestern University): The Politics (Mine and Theirs) of

Revitalizing Black Chicago

Ruth Horowitz (New York University): On the Uses and Abuses of

Membership: Dynamics and Ethics of Participation in the Regulation of

Medicine

Nancy Scheper-Hughes (University of CaliforniaBerkeley): Rotten Trade:

Global Justice and the International Traffic in Human Organs

Discussant: Laura Nader (University of CaliforniaBerkeley)

911pm, 160 Kroeber Hall: Screening of Ruth Behars Adio Kerida,

followed by a debate with Ruth Behar and Jos David Saldvar (Chair of

UCBerkeley Ethnic Studies).

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 11

Wacquant Ethnografeast 11

Day 3 Saturday 14 September 2002

5 Bodies, senses, selves

Loc Wacquant (University of CaliforniaBerkeley, Centre de sociologie

europenneParis): Suffering Beings: Ethnography as Embedded and

Embodied Social Inquiry

Robert Desjarlais (Sarah Lawrence College): A Phenomenology of Dying:

Subjectivity and Death among Nepals Yolmo Buddhists

Gary Alan Fine (Northwestern University): Towards a Peopled Ethno-

graphy: Analyzing Small-Group Culture

Akhil Gupta (Stanford University): Bodily Practices and Rebirth

Discussant: Lawrence Cohen (University of CaliforniaBerkeley)

6 From site(s) to history and back to theory (25pm)

Ulf Hannerz (Stockholm University): Being There . . . and There . . . and

There! Reflections on Multisite Ethnography

Calvin Morrill (University of CaliforniaIrvine), David Snow (University of

CaliforniaIrvine) and Leon Anderson (Ohio State University): Elaborating

Analytic Ethnography: Linking Field Work and Theoretical Development

Paul Willis (Wolverhampton University): Autonomy and Determinacy in

Understanding Cultural Practices

Jean Comaroff (University of Chicago): Ethnography on an Awkward

Scale: The View from the South-African Postcolony

Notes

1 The journal expresses its appreciation to the following institutions, all at

the University of California-Berkeley, for making the conference possible:

the Survey Research Center, the Departments of Sociology and Anthro-

pology, the Institute for the Study of Social Change, the Center for the Study

of New Inequalities, the Townsend Center for the Humanities, the French

Studies, Film Studies, and Ethnic Studies Programs, and the Office of the

Chancellor. Extramural support from the Lal Foundation, the Holbrook

Foundation, and the French Consulate is gratefully acknowledged. I would

like to personally thank my co-organizers, Martn Snchez-Jankowski and

Nancy Scheper-Hughes, for their patience and persistence, and Maureen

Fesler for her flawless management of the event.

2 Several anthropologists noted aloud that it was the first time in their career

that they found themselves in a conference room with throngs of socio-

logists. Conversely, the sociologists candidly confessed to being unfamiliar

with some of the idioms and concerns of anthropologists as expressed at

the lectern and from the floor during discussion. Professional gatherings

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 12

12 E t h n o g r a p h y 4(1)

of anthropologists rarely include more than a token sociologist and vice

versa.

3 See, among a flurry of recent works, Walford (2001) and Zou and Trueba

(2002) for education, Goodale and Starr (2002) for law; Cottle (2000) and

Schlecker and Hirsch (2001) for media and science studies; Herbert (2000)

and McHugh (2000) for geography; Mayne (1999) for history; Wasson

(2000) for design and Rosen (2000) for management; Wolf (1996) for

gender; and Roper and Shapira (2000) for nursing.

4 Adler and Adler (1999) provide a different taxonomy of breeds of ethnogra-

phers, all of which were represented at the Ethnografeast.

5 Read, among more recent papers, Burawoy (2000b and 2001a) and the

interdisciplinary volume on social change in Eastern European societies

after the Soviet collapse (Burawoy and Verdery, 1999); and, for a collec-

tive appraisal and critique of his work by sociologists, the articles by

Robin Leidner, Jennifer Peirce, Heidi Gottfried, Gay Seidman, Steven

Peter Vallas, and Leslie Salzinger in Contemporary Sociology (2001,

305, September 2001, 423444), as well as Burawoys (2001b) own

para-reflexive piece on his predecessor industrial sociologist and ethnog-

rapher Donald Roy.

6 A future special issue of Ethnography on Pierre Bourdieu in the Field

(scheduled for Spring 2004) will feature several original ethnographic texts

by Bourdieu drawn from his early fieldwork in Algeria and in his native

region of Barn in Southern France, as well as critical analyses of their

theoretical and empirical import.

7 The movie was screened before a full house on the opening evening of the

conference in Wheeler Auditorium; it was introduced by Chancellor

Berdahl and followed by a debate with director Pierre Carles and Linda

Williams, Chair of Film Studies at the University of California, Berkeley.

8 The full conference program, with biographical sketches, draft papers

and/or abstracts of the presentations is available on line at http://

cue.berkeley.edu.

References

Adler, Patricia A. and Peter Adler (1999) The Ethnographers Ball Revisited,

Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 28(5): 44250.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1979[1984]) Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement

of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1989[1996]) The State Nobility: Elite Schools in the Field of

Power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre (2002) Le Bal des clibataires. La crise de la socit paysanne

en Barn. Paris: Seuil/Points.

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 13

Wacquant Ethnografeast 13

Bourdieu, Pierre, Alain Darbel, Jean-Paul Rivet and Claude Seibel (1963)

Travail et travailleurs en Algrie. Paris and The Hague: Mouton and Co.

Bourdieu et al. (1993[1999]) The Weight of the World: Social Suffering in

Contemporary Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Burawoy, Michael Boris (1996) From Capitalism to Capitalism via Socialism:

The Odyssey of a Marxist Ethnographer, 19751995, International Labor

and Working-Class History 50: 7799.

Burawoy, Michael Boris (1998) The Extended Case Method, Sociological

Theory 16(1): 433.

Burawoy, Michael Boris (2000a) Marxism After Communism, Theory and

Society 29(2): 151174.

Burawoy, Michael Boris (2000b) A Sociology for the Second Great Trans-

formation, Annual Review of Sociology 26: 693695.

Burawoy, Michael Boris (2001a) Manufacturing the Global, Ethnography

2(2): 147159.

Burawoy, Michael Boris (2001b) Donald Roy: Sociologist and Working Stiff,

Contemporary Sociology 30(5): 453458.

Burawoy, Michael Boris and Katherine Verdery (eds) (1999) Uncertain Tran-

sition: Ethnographies of Change in The Postsocialist World. Lanham, MD:

Rowman & Littlefield.

Burawoy, Michael Boris et al. (1991) Ethnography Unbound: Power and Resist-

ance in the Metropolis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Burawoy, Michael Boris et al. (2000) Global Ethnography. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

Carles, Pierre (2001) Sociology is a Martial Art. Betacam Video/VHS. C-P

Productions (distributed in the United States by Icarus Films, New York,

www.frif.com)

Cottle, Simon (2000) New(s) Times: Towards a Second Wave of News

Ethnography, Communications 25(1): 1941.

Gille, Zsuzsa and Sen Riain (2002) Global Ethnography, Annual Review

of Sociology 28: 271295.

Herbert, Steve (2000) For Ethnography, Progress in Human Geography 24(4):

550568.

Goodale, Mark and June Starr (eds) (2002) Practicing Ethnography In Law.

London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gupta, Akhil and James Ferguson (eds) (1997) Anthropological Locations:

Boundaries and Grounds of a Field Science. Berkeley: University of Cali-

fornia Press.

Mayne, Alan and Susan Lawrence (1999) Ethnographies of Place: A New

Urban Research Agenda, Urban History 26(3): 325348.

Mauss, Marcel (1913) Lethnographie en France et ltranger, La Revue de

Paris 20: 815837.

McHugh, Kevin E. (2000) Inside, Outside, Upside Down, Backward, Forward,

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

01 introduction (jk/d) 5/3/03 8:35 am Page 14

14 E t h n o g r a p h y 4(1)

Round and Round: A Case for Ethnographic Studies in Migration, Progress

in Human Geography 24(1): 7189.

Peirano, Mariza G. S. (1998) When Anthropology is at Home: The Different

Contexts of a Single Discipline, Annual Review of Anthropology 27:

105128.

Roper, Janice M. and Jill Shapira (2000) Ethnography in Nursing Research.

Walnut Creek, CA: Altamira Press.

Rosen, Michael (2000) Turning Words, Spinning Worlds: Chapters in Organiz-

ational Ethnography. London: Routledge.

Schlecker, Markus and Eric Hirsch (2001) Incomplete Knowledge: Ethnogra-

phy and the Crisis of Context in Studies of Media, Science and Technology,

History of the Human Sciences 14(1): 6987.

Stacey, Judith (1999) Ethnography Confronts the Global Village: A New Home

for a New Century?, Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 28(6):

687697.

Walford, Geoffrey (ed.) (2001) Ethnography and Education Policy. Samford,

CT: JAI Press.

Wasson, Christina (2000) Ethnography in the Field of Design, Human

Organization 59(4): 377388.

Wolf, Diane (ed.) (1996) Feminist Dilemmas in Fieldwork. Boulder, Co:

Westview Press.

Zou Yali and Enrique T. Trueba (eds) (2002) Ethnography and Schools: Quali-

tative Approaches to the Study of Education. Lanham, MD: Rowman &

Littlefield.

Downloaded from eth.sagepub.com at University of Liverpool on March 23, 2013

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The BreastDocumento4 páginasThe BreastLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Culture Has A InfluenceDocumento10 páginasCulture Has A InfluenceLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- PAHO Breast Cancer Factsheet 2014Documento2 páginasPAHO Breast Cancer Factsheet 2014Luis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Pigg 2013 Ethnography As Action in Global Health. SS&M 99Documento8 páginasPigg 2013 Ethnography As Action in Global Health. SS&M 99Luis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Prevenitve Medice PDFDocumento7 páginasPrevenitve Medice PDFLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Jena Et Al-2017-Health Services ResearchDocumento16 páginasJena Et Al-2017-Health Services ResearchLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Methods To Increase Participation in Organised Screening Programs A Systematic ReviewDocumento16 páginasMethods To Increase Participation in Organised Screening Programs A Systematic ReviewLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Invitation Schemes On Breast Cancer Screening Coverage A Cohort Study From Copenhagen, DenmarkDocumento7 páginasImpact of Invitation Schemes On Breast Cancer Screening Coverage A Cohort Study From Copenhagen, DenmarkLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Mammography Screening Attendance Meta-Analysis of The Effect of Direct-Contact InvitationDocumento9 páginasMammography Screening Attendance Meta-Analysis of The Effect of Direct-Contact InvitationLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Impact of Invitation Schemes On Breast Cancer Screening Coverage A Cohort Study From Copenhagen, DenmarkDocumento7 páginasImpact of Invitation Schemes On Breast Cancer Screening Coverage A Cohort Study From Copenhagen, DenmarkLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Impact of Invitation Schemes On Breast Cancer Screening Coverage A Cohort Study From Copenhagen, DenmarkDocumento7 páginasImpact of Invitation Schemes On Breast Cancer Screening Coverage A Cohort Study From Copenhagen, DenmarkLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Arthur Kleinman The Illness Narratives Suffering Healing and The Human ConditionDocumento46 páginasArthur Kleinman The Illness Narratives Suffering Healing and The Human Conditionperdidalma62% (13)

- Telephone Counseling and Attendance in ADocumento7 páginasTelephone Counseling and Attendance in ALuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Bonfill, Strategias For IncreasingDocumento3 páginasBonfill, Strategias For IncreasingLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Delaying Diagnosis en CamaDocumento6 páginasDelaying Diagnosis en CamaLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Text-Message Reminders Increase Uptake of Routine Breast Screening Appointments A Randomised Controlled Trial in A Hard-To-reach PopulationDocumento6 páginasText-Message Reminders Increase Uptake of Routine Breast Screening Appointments A Randomised Controlled Trial in A Hard-To-reach PopulationLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Breast Cancer Screening - Prevalence of Disease in Women Who Only Respond After An Invitation ReminderDocumento2 páginasBreast Cancer Screening - Prevalence of Disease in Women Who Only Respond After An Invitation ReminderLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- CancerEpi 0Documento11 páginasCancerEpi 0Luis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Breast Cancernearly DetectionDocumento8 páginasBreast Cancernearly DetectionLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Breast Cancer Screening MexicoDocumento11 páginasBreast Cancer Screening MexicoLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Arthur Kleinman The Illness Narratives Suffering Healing and The Human ConditionDocumento46 páginasArthur Kleinman The Illness Narratives Suffering Healing and The Human Conditionperdidalma62% (13)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Hipotermia PeditricDocumento6 páginasHipotermia PeditricLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- Canada Evaluaciom ScreeningDocumento15 páginasCanada Evaluaciom ScreeningLuis Covarrubias GutierrezAinda não há avaliações

- The Earliest Hospitals EstablishedDocumento3 páginasThe Earliest Hospitals EstablishedJonnessa Marie MangilaAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Outgoing Global Volunteer: OG V BramantyaDocumento12 páginasOutgoing Global Volunteer: OG V BramantyaPutri Nida FarihahAinda não há avaliações

- Milton Friedman - The Demand For MoneyDocumento7 páginasMilton Friedman - The Demand For MoneyanujasindhujaAinda não há avaliações

- PPT7-TOPIK7-R0-An Overview of Enterprise ArchitectureDocumento33 páginasPPT7-TOPIK7-R0-An Overview of Enterprise ArchitectureNatasha AlyaaAinda não há avaliações

- Moral Dilemmas in Health Care ServiceDocumento5 páginasMoral Dilemmas in Health Care ServiceYeonnie Kim100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Frivaldo Vs Comelec 1996Documento51 páginasFrivaldo Vs Comelec 1996Eunice AmbrocioAinda não há avaliações

- Merger and Demerger of CompaniesDocumento11 páginasMerger and Demerger of CompaniesSujan GaneshAinda não há avaliações

- Managing New VenturesDocumento1 páginaManaging New VenturesPrateek RaoAinda não há avaliações

- BARD 2014 Product List S120082 Rev2Documento118 páginasBARD 2014 Product List S120082 Rev2kamal AdhikariAinda não há avaliações

- Customer Perception Towards E-Banking Services Provided by Commercial Banks of Kathmandu Valley QuestionnaireDocumento5 páginasCustomer Perception Towards E-Banking Services Provided by Commercial Banks of Kathmandu Valley Questionnaireshreya chapagainAinda não há avaliações

- Unilever IFE EFE CPM MatrixDocumento7 páginasUnilever IFE EFE CPM MatrixNabeel Raja73% (11)

- Inclusive Approach For Business Sustainability: Fostering Sustainable Development GoalsDocumento1 páginaInclusive Approach For Business Sustainability: Fostering Sustainable Development Goalsaakash sharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Among The Nihungs.Documento9 páginasAmong The Nihungs.Gurmeet SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Athet Pyan Shinthaw PauluDocumento6 páginasAthet Pyan Shinthaw PaulupurifysoulAinda não há avaliações

- Standard Oil Co. of New York vs. Lopez CasteloDocumento1 páginaStandard Oil Co. of New York vs. Lopez CasteloRic Sayson100% (1)

- Chapter 3. Different Kinds of ObligationDocumento17 páginasChapter 3. Different Kinds of ObligationTASNIM MUSAAinda não há avaliações

- Armenia Its Present Crisis and Past History (1896)Documento196 páginasArmenia Its Present Crisis and Past History (1896)George DermatisAinda não há avaliações

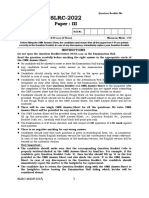

- SLRC InstPage Paper IIIDocumento5 páginasSLRC InstPage Paper IIIgoviAinda não há avaliações

- Community-Based Health Planning Services: Topic OneDocumento28 páginasCommunity-Based Health Planning Services: Topic OneHigh TechAinda não há avaliações

- KELY To - UE Section B Writing Topics 1989-2010Documento16 páginasKELY To - UE Section B Writing Topics 1989-2010Zai MaAinda não há avaliações

- Criticism On Commonly Studied Novels PDFDocumento412 páginasCriticism On Commonly Studied Novels PDFIosif SandoruAinda não há avaliações

- Ermitage Academic Calendar IBP 2022-23Documento1 páginaErmitage Academic Calendar IBP 2022-23NADIA ELWARDIAinda não há avaliações

- PolinationDocumento22 páginasPolinationBala SivaAinda não há avaliações

- Invited Discussion On Combining Calcium Hydroxylapatite and Hyaluronic Acid Fillers For Aesthetic IndicationsDocumento3 páginasInvited Discussion On Combining Calcium Hydroxylapatite and Hyaluronic Acid Fillers For Aesthetic IndicationsChris LicínioAinda não há avaliações

- Salesforce - Service Cloud Consultant.v2021!11!08.q122Documento35 páginasSalesforce - Service Cloud Consultant.v2021!11!08.q122Parveen KaurAinda não há avaliações

- (Group 2) Cearts 1 - Philippine Popular CultureDocumento3 páginas(Group 2) Cearts 1 - Philippine Popular Culturerandom aestheticAinda não há avaliações

- "Land Enough in The World" - Locke's Golden Age and The Infinite Extension of "Use"Documento21 páginas"Land Enough in The World" - Locke's Golden Age and The Infinite Extension of "Use"resperadoAinda não há avaliações

- Suffixes in Hebrew: Gender and NumberDocumento11 páginasSuffixes in Hebrew: Gender and Numberyuri bryanAinda não há avaliações

- Atlas Engineering Early Australian Ship BuildingDocumento8 páginasAtlas Engineering Early Australian Ship BuildingparkbenchbruceAinda não há avaliações

- Listening Test 2Documento5 páginasListening Test 2teju patneediAinda não há avaliações