Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

McCrackenArtforum PDF

Enviado por

Pa To N'CoTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

McCrackenArtforum PDF

Enviado por

Pa To N'CoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

In Search of . . .

John McCracken got filed under Finish Fetish

and LA Minimalism in the first phases of his

career, which worked only to his short-term

LINDA NORDEN ON THE ART OF JOHN MCCRACKEN advantage. McCrackens peers never really found

a way to name his paranormal objects and objec-

tives. It took a younger generation, readier to read

our world as occupied by multiple intelligences

and beings, to appreciate just how possessed

and wildly empathetic McCracken was as an

artist. And its still not clear what McCrackens

extraordinarily concentrated, homemade extra-

terrestrialsor the escalating consciousness

within which he imagined himself and his art

might represent. To begin assessing the legacy

of this singular artist, who passed away in April,

Below: View of John McCracken:

New Work in Bronze and Steel, Artforum asked curator and critic Linda Norden

Opposite page: John McCracken,

Magic, 2008, stainless steel.

2010, David Zwirner, New York.

From left: Dimension, 2010; Star, to investigate.

Installation view, Napa Valley, CA, 2010; Election, 2010; Infinite, 2010.

2009. Photo: Grant Delin. Photo: Cathy Carver.

270 ARTFORUM OCTOBER 2011 271

Id like to see you visually, I say to him. Teilhard de Chardin, and written at the moment of the first US moon landing, as the explosive MORGAN FISHER

You wouldnt make sense of it. 60s segued into the sleeper 70s. As a child of the New Age, wrote Youngblood, making

I say, Try anyway.1 early use of that term, I have lived in Los Angeles for over forty years. One reason is that Los

for whom nature is the solar system and reality is an invisible environment of messages, I am Angeles is an international art capital without also being a capital of the art

BY HIS OWN ADMISSION, John McCrackens art is difficult to encapsulate in language. Words market. Perhaps it is the preeminent such city. The distance from the market

naturally hypersensitive to the phenomenon of vision. I have come to understand that all language

just dont happen to be my tools, he wrote in 1965 in an early sketchbook. Its an odd dis- reduces the pressure that it exerts in general and moderates the frenzies

is but substitute vision . . . [t]he history of the living world can be summarized as the elaboration

claimer for an artist who filled countless such notebooks and sketchbooks with working of ever more perfect eyes within a cosmos in which there is always something more to be seen.6 that it routinely produces. Los Angeles has its own version of these, but the

drawingsand words. Lots of words. In the mid-60s, during the first years of a career that sprawl helps to diffuse them. And the auctions here dont make headlines.

took off even before his 1965 graduation from the California College of Arts and Crafts, Youngbloods notion that there is always something more to be seen (citing Teilhard) posed The absence of market pressures and the abstractness that the monotony

McCrackens sketchbooks record a relentless barrage of questions, in search of some explana- an ever-expanding visionone rooted not in an obdurate body viewing an obdurate object, of the sprawl produces give me freedom. Freedom lets me take the long

tion for the objects that seemed to present themselves to him fully formed, abstract but distinct but in a kind of scaleless, infinite universe rife with unknown bodies and possible intelligences. view. I came of age in the 1960s. Some of my work has been in relation

and powerfully affecting. Whether of his own devisinga radio coated in monochrome paint, His was not a full-fledged critical position, but instead offered detailed instances of how a to things that happened even longer ago than that, and sometimes on the

sayor a projection from the outside world, such as an Egyptian obelisk, these objects seemed technologically and pharmaceutically augmented vision might lead to a mode of perception other side of the world. To me these are as recent and near and available

to demand account. we could not predict. as what I see when I look out the window. I feel Los Angeles has given me

There are untold correlations between McCrackens personal, probing notes to himself and As it happens, on the day of the opening for McCrackens last gallery show, New York was the freedom to develop my work in relation to things that are

what is operative in his art. Yet while his sculptural forms aimed for something much larger hit at almost exactly 6:00 pm by what was later deemed a tornado, if only because of the not here and not now, some of which have been important to me from the

than individual subjective expression, they have stubbornly eluded the theoretical terms that destruction it wreaked in a mere ten minutes. On that storm-stressed evening, the weak and beginning. I doubt I would have found this freedom elsewhere, although

qualified so much Minimalist and post-Minimalist art.2 In this sense, McCracken is not wrong gloomy natural light and looming empty white walls of David Zwirner gallery were a far cry I cant know for certain.

when he says words are not his tools; languageor rather critical languagehas not served from the bright desert glow in the photo outside McCrackens studio, where the seven solid

his art well precisely because his art is not conceived in language. Maybe its that instead of metal sculptures on exhibitthree bronze planks and four rectangular steel columnswere

using words to really build things, he added in the same sketchbook, I use them in an attempt conceived. At Zwirner, the metal slabs, each meticulously honed and polished to a mirror

to approximate my thought patterns. The singular forms McCracken worked so concertedly gleam, oscillated between spectacular physical presence and something more eerily spectral.

to develop from 1965 onward, you might say, arose alongside language, not with it; they The bronze planks, glowing gold, exuded an incandescent aura. Yet their unusually shallow-

contain a multitude of competing ideas and beliefs the artist entertained in service of a vision angled prop against the wall meant that the perception of solid mass in these sculptures

at once attuned to and ranging beyond mid-60s high-art formulations, pop culture, politics, never fully disappeared. The insistently vertical stainless-steel columns, by contrast, icily

and techno-explorations. And if his perspective was more Los Angeles than New York, it was reflected odd vanishing points and corners of the gallery made visible only by the lines where

also more McCracken than LA. For all the artists indisputable postwar optimism, McCrackens walls and floor met in reflection, multiplying themselves and the space ad infinitum, to

vision was both more idiosyncratic and more millennial than anyone could have guessed at disorienting effect.

the time.

MCCRACKEN WORKED IN METAL for more than two decades, beginning with stainless steel in

MY WORKS, McCracken announced a year ago, are minimal and reductive, but also maxi- 1988. But he added bronze to his repertoire only in 2005. Relative to the years he spent Morgan Fisher, Cinemascope 2.35:1, 2004, sandblasting on mirror, 24 x 56 14".

mal. I try to make them concise, clear statements in three-dimensional form, and also to take experimenting with and refining his use of colored paint, lacquer, and polyester resin on wood,

them to a breathtaking level of beauty.3 These words came in the unlikely context of the press

Above: John McCracken outside Below: John McCracken, Brown John McCracken, Flash, 2010,

release for what was to be his last gallery exhibition, in New York in 2010; they were a his studio, Santa Fe, NM, ca. 2010. Block in Three Parts, 1966, bronze, 100 x 16 x 2".

reminder of McCrackens unorthodox relationship to the critical pieties of the Minimalist Photo: Gail Barringer. lacquer, wood. Installation view.

mind-set. I think minimalist work is not always so minimalist, McCracken elaborated on

another occasion, especially when you really see it and think about itor, say, try to accu-

rately describe it. But my tendency was to make my works more sensuous than most, and more

what I thought of as beautiful. I thought that if something was beautiful, one could enjoy look-

ing at it and therefore stand to apprehend the form in a full wayintellectually, emotionally,

and experientially.4

In the photo accompanying the release, McCracken standson a stepladder!tall, wiry,

Morgan Fisher, Silent 1.33:1, 2004, sandblasting on mirror, 24 x 31 78".

stiffly erect, as if in metaphysical salute, a human lightning rod in the full glare of a New

Mexico afternoon sun. Who but McCracken, I thought to myself, could declare with such

emphatic delight that he is trying to take his work to a breathtaking level of beauty? And

what self-respecting first-generation Minimalist would allow himself to be photographed

gazing up and out into the immeasurable expanse of a deep azure desert sky, atop a stepladder?5

There are intimations of other maverick American seers in McCrackens pose: Georgia

OKeeffe, Captain Kirk, even Robert Smithson gazing over the Great Salt Lake and his Spiral

Jetty. But its hard to picture Donald Judd staring into distant space or invoking the adjective In McCrackens work, perfection

beautiful, let alone the breathtaking variety. As with everything McCracken said and did, both amounts to a perceptual erasure,

the words and the image here conveyed an artist at once deeply earnest, deadpan, and possessed a destabilization at odds with

of an imaginatively liberated grasp of what the 60s had to offer.

When I saw the press release last fall, McCrackens horizon-scanning squint sent me back

the stark gestalt, the stamped-out

to a more bombastic declarationthe opening salvo to Gene Youngbloods groundbreaking shape, usually identified with Morgan Fisher, Academy 1.37:1, 2004, sandblasting on mirror, 24 x 32 34".

book Expanded Cinema, inspired by both R. Buckminster Fuller and the philosopher Pierre Minimalist form.

272 ARTFORUM OCTOBER 2011 273

this was a new material marriage. (The planks on view at Zwirner, for example, were the first As if in lieu of Kubricks 2001 PIERO GOLIA

hed cast in bronze.) To the extent that a material object is perfectible, these last metal planks

and plinths were perfecttheir surfaces flawless. Craft is there because it has to be,

spaceship, McCracken understood

Whether by manifest destiny or on a quest for gold, I set out for what was

McCracken often said. If something sticks out, its a distraction. I aim for a perfection that his planks from the get-go as supposed to be a two-week LA vacation and stayed for ten years. And it

allows something to be seen; not as an end. Even in the sunnier climes and outdoor settings a way to make contact between didnt take long, driving the never-ending stretches of freeway and boule-

in which McCrackens earlier metal columns have been sited, however, perfection amounts worlds, from within the confines vards that run back and forth across the City of Angels, to feel its dispro-

to a perceptual erasure, a destabilization at odds with the stark gestalt, the stamped-out shape,

usually identified with Minimalist form. The material identity of McCrackens objects is pred-

of his studio space. portionate, almost inhuman scale. Im not sure what Mason Williams and

Ed Ruscha were thinking when they decided to drive Ruschas black Ford

icated on surfaces so pristine that the objects they define can never be fully apprehended. sedan from Oklahoma to Los Angeles in 1956, but it set into motion what

These sculptures were indeed simultaneously Minimalist, maximalist, and breathtakingly would become an epic future for them. By the time I arrived, the landscape

beautiful. Their surfaces, like McCrackens more subtly reflective colored-epoxy-resin entities, had changed somethe studio that Richard Jackson occupied on Colorado

inflected and activated the space around them in good Minimalist fashion, generating effects Boulevard had become a Victorias Secretbut just like any actor, LA has

contingent on the viewers shifting position and perception. But McCracken had more in mind weathered its ups and downs.

than these isolated phenomenological attributes. The inherent and affective properties of the I remember, early on, meeting Eric Wesley. We were at La Buca on Melrose

John McCracken, Yellow Plank, Above: John McCracken, Right: Detail of a page from a

metal works introduce another order of association and perfectibility. They facilitate a shift in 1968, polyester resin, fiberglass, Pyramid, 1974, acrylic and wood, sketchbook by John McCracken, and started talking about what would become the Mountain School. It was

emphasis from an earlier, more conventional opposition between painting and sculpture in the wood, 94 x 14 14 x 1 14". 12 x 16 x 16". 1966. the time of Black Pussy and the Dub Club. And then, everything started

painted wooden sculptures. happening so fast, and with all of the perfect, Hollywood-style tears and

Paradoxically, in the colored sculptures, where the paint is literally on the surface, the effect joy you might expect. O brave new world!

McCracken worked hard to achieve was one of solid color. He spoke of color as an abstract planks pointed beyond Minimalism, toward a post-Minimal interest in physical force and

quality that he wanted to treat as form, as a quality that thoroughly permeates the surface, process. But McCracken himself never limited the planks to such earthly physical properties.

so as to feel like its color through and through. To achieve this, McCracken applied liquid In a 1966 drawing in one of his sketchbooks, for example, there are little cartoon lightning

resincolor as liquidonto precisely cut, sometimes fantastically faceted, hollow plywood bolts bracketing a pair of planks like electric quotation marks, an indication, perhaps, of

volumes.7 The liquid color would cure solid. He then fastidiously sanded and buffed between McCrackens recognition of the power that this particular placement conferred on a simple

layers to yield, almost magically, the translucent color-form sheen that functionally obliterates plywood board. As if in lieu of Kubricks 2001 spaceshipa vehicle that physically transported

the additive process. (From liquid to solid and then back to liquid again, in the visual sense, people and things between worlds but that, unlike his monolith, ultimately failedMcCracken

said McCracken.) 8 The result is a fathomless, mercurial mass. This labor-intensive process was understood his planks from the get-go as a way to make contact between worlds, from within

developed early on, in the late 60s, and refined over the yearsbut never substantively altered, the confines of his studio space. At some point after his late-60s eureka, McCracken came to

save for a series of planks made in the mid-70s, to which McCracken applied multiple colors read the planks as conduitsas almost literally electric, Id like to say. No longer simply link-

with a brush to more painterly effect. ing two distinct spaces, they declared and charged a unified cosmic field within which

The extreme opacity and density of the cast-metal sculptures, on the other hand, are sensed McCracken could reaffirm his conviction that alien, as well as more familiar, intelligences are

but never really observable: Nowhere does McCracken more fully succeed in eliciting a perception at large. As he said in 1997:

of dematerialization than in those last steel and bronze steles. Unlike the solid huehowever

miasmicof the colored planks, in the metal works the combination of hard edge and fully reflec- My own work has puzzled meespecially as it relates to the plank. I kept coming back to making

planks and I kept wondering if I was being habitual or obsessive or responding to demand, or if

tive surface leads to a vertiginous transparency, a dissipation of vision. To be in the presence of Piero Golia, Luminous Sphere, 200810, mixed media. Installation view, Standard Hotel,

there was more to this plank form than I consciously realized. I wondered if they were a life form Los Angeles, 2010. Photo: Joshua White.

these cast-metal entities is almost dizzyingly uncanny no matter the site; in the denuded, supremely

from somewhere that was channeling through me and it didnt make any difference if I understood

elegant commercial spaces of a gallery such as Zwirner, the extreme contrast between the them or not. It worried me a bitI believe in being intuitive, but not being unconscious . . . [W]hen

perfection McCracken achieves in his sculptures and the spiraling devolution of the profoundly you set them at an angle then you have something that shifts away from our reality. Its partly in

unsettled world in which they hover can be truly terrifying. This kinesthetic thrill hints at the the world and partly out of the world. Its like a visit.9

artists ability to sustain the deep-seated optimism of a child of the new age 60s and project it

onto and into the electronically charged spaces of a newer, digital age. Inspired as they are by That the boards really did function as banal, material objects and as metaphoric conduits is

the imagination of that adventurous decade, McCrackens stubbornly perfect objects now precisely what must have made them so difficult to accommodate within the discourse of

stand as weird witness to a fallen dream in a world thats lost its bearings. Minimalism or even post-Minimalism. As with the artists interest in hand-controlled craft,

the notion that McCrackens reductive forms were in the service of something external to their

EVEN IN THEIR EARLIEST INCARNATIONS, McCrackens freestanding, upright posts and plinths making ran directly counter to both Minimalist and post-Minimalist assertions of material

and pyramids and ziggurats were closer to the matte-black monolith in Stanley Kubricks 2001: and process and suspicions of top-down belief systems. McCrackens relationship to

A Space Odyssey than to the Minimalist cube. They were singular and not specific objects. Minimalism, in other words, was as only one means toward a more open, maximal end.

In other words, they were never intended as objects in their own right, but as vehicles for In this sense, McCrackens precise surfaces and halating color or reflectivity are meta-

something more metaphysical. And McCrackens planks, whose configuration he stumbled on physical in that they suggest a realm beyond the literal, the profane, the real. But they do not

in 1966, did something more. These leaning boards marked his eureka, as he put itthe point toward an ideal gestalt, as might be said of East Coast Minimalism, or to the limits of

accident that revealed the project. This eureka did not simply result from a technical process physiological perception and material refinement, as in Finish Fetish. Nor do they indicate a

or a deliberate action. It entailed a recognition: The fact that the board touched wall and floor belief in any sole omniscient God or being. Rather, cast metal, mirror polished, aids and abets

simultaneously rendered it both thing and bridge. The very contingency of the plankstheir tilt- the associations with extraterrestrial intelligences and communications that increasingly came

ing, their assent to gravityintroduced a host of possible associations, from anthropomorphism to dominate McCrackens metaphysical imagination. McCracken points to a dynamic, almost

to something profoundly futuristic. The works became at once exotic and problematic, particu- dialectical relationship between an ever-expanding consciousness and an ever-unknowable

larly with respect to the Minimalist context to which McCrackens earlier objects could be more future visionthe kind that Youngblood sketches, one that is technologically enhanced and

easily ascribed. Art historian James Meyer, writing thirty-six years later, proposed that the fundamentally alien.

274 ARTFORUM OCTOBER 2011 275

McCracken points to a dynamic, almost [The] ubiquity and the shocking emptiness of his adamantine slabs, wedges, and columns led me

LARRY BELL

dialectical relationship between an to suspect that the curators mean to wholly reinvent him, for the purposes of the exhibition, as a

I am an inveterate cigar smoker. I cannot pass a cigar store without going

ever-expanding consciousness and an goofy character at whom we can all laugh, his ham-fisted, early psychotropic paintings heightening

in to examine the goods. Someone once gave me an old box of Larry Bell

our amusement. For me, he became less and less an artist; his polished sculptures became the ulti-

ever-unknowable future vision. mate image of banality, doorstops to prop open the portals through which other forms may migrate brand cigars, and I eventually made a piece by burying this box in a heap

in a series of color-coded juxtapositions.11 of cigar bands that I had been collecting for almost five years. In the

San Fernando Valley, where I grew up, there are cigar stores next to cigar

In its own way, Enwezors criticism is evidence of the affective power McCracken invokes stores. In some areas of LA, there are taco stands next to taco stands and

through his sculptures and their perfectionist material presence: Reflection above all. Given sushi bars next to sushi bars. In Hollywood, there are topless bars next

Enwezors commitment to socially and politically engaged art, and minus any investment in to topless bars and bookstores next to bookstores. We are constantly

McCrackens extraterrestrial, metaphysical channeling or his near-fetishizing embrace of craft, navigating right angles and blind corners. This peripheral density has had

a shiny bronze column can only be a monument to materialism and vanity. Enwezors pique a profound effect on my work, and Im sure it precipitated my desire to

underscores both the success and the threat that McCrackens sculpture represents now. In the keep my sculptures simple.

context of 2011, his art may appear to newer skeptics as irrelevant at best, and immorally Since 1959, Ive kept a studio in Venice Beach. Many visitors find it to

complicit with global capitalism at worst. be a kooky and weird place, but I consider it home. Venice is a particular

But the context McCracken seemed more intent on retrieving was closer to a religious, not kind of reality, with a large homeless population, many street performers,

worldly, recognition. His was an art predicated on an acknowledgment of all that remains and every shape of person one can imagine (and a few shapes that one

beyond comprehension. Those same early notebooks include references to Barnett Newman cannot imagine). In my opinion, this landscape is not weird at all; in fact,

Left: John McCracken, Swift, 2007, as well as to the vestigial remnants of druid monuments; to painting that eschews the corporeal its realas real as the reflections in my glass pieces. The light in Venice is

bronze. Installation view, Kunsthalle Below: John McCracken, Untitled, quite special, and I suspect that the celebration of the light is in the work,

Fridericianum, Kassel. From 1974, lacquer, polyester resin,

identification on which Christian art depends and monoliths whose meaning eludes verbal or

I have often wondered what Smithson might have made of McCrackens monolithic oddities Documenta 12. Photo: Jens Zieher. fiberglass, wood, 93 58 x 17 78 x 2". visual definitionjust like the mysterious entities McCracken worked to conjure out of body too. With my glass cubes, I wanted to shape the surrounding light as it

circa 1966, or the uncannily leaning planks that soon followed, had these inspired him to write in his later years, or like Kubricks black monolith. This explains the earnest appreciation of passed through the sculptures, compressing the hazy atmosphere in which

as he did on Judds work in the essay The Crystal Land.10 Noting the discrepancy between many who saw McCrackens work as if for the first time at Documenta. But it also explains they were conceived.

Judds insistently rational accounts and his eccentrically fabricated specific objects, Smithson the anger. I, for one, have experienced both. I have also tried to imagine, la McCracken, a

allows that the first time I saw Don Judds pink plexiglas box, it suggested a giant crystal universe populated by intelligences other than we humans, one premised on distinctions

from another planet. McCracken shares much of Smithsons otherworldly sight, his meta- between that which is discernible and that which is comprehensible. I have wondered how

physical yearning. Yet he diverges from Smithsons recourse to transcendence, from the notion McCrackens sculpture might function in such a world, or what kind of belief system would

that worldly physical and historical experience might be surpassed by a crystalline entropy. embrace his art as its totems. As it is, McCrackens exquisite objects exist as surreally luminous,

McCrackens metaphysics does not end in eschatology but in empathy. haptic manifestations not of a world that wasor even of a world that could bebut of a

vision still unclear. McCracken, you might say, made art for an inwardly yearning generation,

BY 1986, when the bicoastal curator Edward Leffingwell organized McCrackens first retro- blinded by the light.

spective, for the Institute for Art and Urban Resources, P.S. 1, the variety of works gathered LINDA NORDEN IS A WRITER AND CURATOR BASED IN NEW YORK. For notes, see page 340.

under the title Heroic Stance: The Sculpture of John McCracken 19651986 still seemed

bereft of adequate critical assessment. McCracken was hardly unknown at the time, but his

presence in the late 70s, especially on the East Coast, had become less conspicuous than a

decade earlier. In the context of late-80s New York, at the height of the aids epidemic,

McCrackens quasi-Minimalist volumes and quasi-anthropomorphic, quasi-alien planks fell

through a different set of critical cracks. The catalogue essays and many of the reviews analyzed

the planks in terms of the more narrowly formal opposition of painting versus sculpture, or

asserted a broadly earnest plea on behalf of McCrackens heroic aspirations.

At the time, critics also suggested that McCrackens best days had come and gone. The

exhibitions impact, which in retrospect seems considerable, came belatedly. Indeed, in the Larry Bell, Untitled Standing Wall, 197072, glass-coated Iconel. Installation view,

Pasadena Art Museum, Pasadena, CA, 1972. Photo: Frank J. Thomas.

decades following the P.S. 1 show, McCrackens reception has both expanded and flourished.

The sticking points of an earlier generations criticismmetaphor, anthropomorphism, any-

thing that smacked of transcendenceno longer stuck. His embrace of the tabloid metaphys-

ics of parallel universes and intelligent others only added to the resonance of his eccentric, not

to say crackpot, enterprise.

Today, McCrackens art troubles yet another sort of established orthodoxy, one that remains

deeply suspicious not of allusions (or even of romantic transcendence), but of material objects

themselves. This suspicion was expressed in an otherwise inexplicably angry response to the

extensive representation of McCrackens work at Documenta 12 in 2007. In addition to show-

casing the entire range of McCrackens various sculptural and relief objects, the exhibition

included a group of his rarely exhibited Mandala paintings from the early 70s. For many

younger artists unfamiliar with McCrackens project, the show had a revelatory impact. But

for curator and critic Okwui Enwezor, this particular presentation of McCrackens work John McCracken, Abritaine, 1972,

elicited a baffled, deep-seated outrage. In his review, Enwezor wrote: oil on canvas, 30 x 30".

276 ARTFORUM OCTOBER 2011 277

NOTES

1. From John McCracken; Remote Viewing/Psychic Traveling; MarApr., 1997, Frieze, no. 33 (JuneJuly 1997):

6063.

2. Unlike his East Coast contemporaries, McCracken addressed his writings to himself. And unlike some of his

West Coast contemporaries, he didnt teach. Though pages from the sketchbooks were exhibited in his 1986

retrospective, and excerpts appeared in various essays and reviews over the years, none of these texts were

published until 2008, when David Zwirner gallery produced a facsimile of the original 196567 sketchbooks.

3. McCracken, quoted in the press release for his SeptemberOctober 2010 exhibition at David Zwirner gallery.

4. Unless otherwise noted, McCrackens observations are from a conversation with the artist recorded in New

York, July 10, 2010.

5. The stepladder comes off as armature or propan association McCracken carefully conceals in his painted

wood and resin sculptures. (In fact, the photograph was taken by McCrackens widow, Gail Barringer, who notes

that McCracken wanted the stepladder cropped.)

6. Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema (New York: Dutton, 1970), 45.

7. McCrackens use of colored resinslacquer, then polyesterfollowed his initial use of colored paint and some

less than satisfactory experiments with reflective automobile paints, Finish Fetish materials all. For an extensive

discussion of McCrackens materials and methods, see Patrick Meagher and Yunhee Mins interview with

McCracken in The Silvershed Reader (New York: Silvershed, 2008), 4687.

8. McCracken, interviewed by Meagher and Min, The Silvershed Reader, 56.

9. Dike Blair, Otherworldly: Interview with John McCracken, Purple Prose, no. 13 (Winter 1998).

10. Robert Smithson, The Crystal Land, (1966), in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, ed. Jack D. Flam

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), 79.

11. Okwui Enwezor, History Lessons, Artforum, September 2007, 384.

278 ARTFORUM

Você também pode gostar

- William York Tindall - A Reader's Guide To James JoyceDocumento301 páginasWilliam York Tindall - A Reader's Guide To James Joycekoloplet100% (19)

- Charlie Gere Essay For Screen PDFDocumento6 páginasCharlie Gere Essay For Screen PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- William York Tindall - A Reader's Guide To James JoyceDocumento301 páginasWilliam York Tindall - A Reader's Guide To James Joycekoloplet100% (19)

- Fulltext PDFDocumento79 páginasFulltext PDFAnonymous R99uDjYAinda não há avaliações

- 0204 948 ESMAY PaperDocumento9 páginas0204 948 ESMAY PaperPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Mari X Ikea PDFDocumento12 páginasMari X Ikea PDFPa To N'Co100% (1)

- Systemic Painting: An Alternative Tradition from the 1950sDocumento72 páginasSystemic Painting: An Alternative Tradition from the 1950sPa To N'Co50% (2)

- Jepp ViewDocumento118 páginasJepp ViewGPSInternationalAinda não há avaliações

- Auto Destructive Art Text RoutledgeDocumento19 páginasAuto Destructive Art Text RoutledgePa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Gormley's EVENT HORIZON Sculptures Explore the Disappearance of ExperienceDocumento4 páginasGormley's EVENT HORIZON Sculptures Explore the Disappearance of ExperiencePa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Leseprobe 9783791349688 PDFDocumento22 páginasLeseprobe 9783791349688 PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Wright Disappearing PDFDocumento125 páginasWright Disappearing PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Peter Halley PDFDocumento11 páginasPeter Halley PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Leseprobe 9783791349688 PDFDocumento22 páginasLeseprobe 9783791349688 PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Superflex Freesollewitt WWW PDFDocumento114 páginasSuperflex Freesollewitt WWW PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- UnbalancedDocumento2 páginasUnbalancedPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Duve Thierry de Pictorial Nominalism On Marcel Duchamps Passage From Painting To The Readymade PDFDocumento255 páginasDuve Thierry de Pictorial Nominalism On Marcel Duchamps Passage From Painting To The Readymade PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Filtration Donald Judd Analysis PDFDocumento156 páginasFiltration Donald Judd Analysis PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- minimalismPRESENTATION PDFDocumento56 páginasminimalismPRESENTATION PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Duve Thierry de Pictorial Nominalism On Marcel Duchamps Passage From Painting To The Readymade PDFDocumento255 páginasDuve Thierry de Pictorial Nominalism On Marcel Duchamps Passage From Painting To The Readymade PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Kenneth Noland PDFDocumento7 páginasKenneth Noland PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Promo - Pedro Cabrita Reis - South WingDocumento52 páginasPromo - Pedro Cabrita Reis - South WingPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis Final MoweryDocumento79 páginasThesis Final MoweryPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- GeorgGudni SMLDocumento180 páginasGeorgGudni SMLeternoAinda não há avaliações

- Duve Thierry de Pictorial Nominalism On Marcel Duchamps Passage From Painting To The Readymade PDFDocumento255 páginasDuve Thierry de Pictorial Nominalism On Marcel Duchamps Passage From Painting To The Readymade PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Tony Smith Moma PDFDocumento209 páginasTony Smith Moma PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Tony Smith Moma PDFDocumento209 páginasTony Smith Moma PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Roquet-Reencountering Lee Ufan PDFDocumento14 páginasRoquet-Reencountering Lee Ufan PDFPa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- RJCS 25 Voices of Mono-Ha Artists Contemporary Art in Japan Circa 1970Documento62 páginasRJCS 25 Voices of Mono-Ha Artists Contemporary Art in Japan Circa 1970Pa To N'CoAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- EISENMAN Conceptual Architecture DefinitionDocumento16 páginasEISENMAN Conceptual Architecture DefinitionSammy NguyenAinda não há avaliações

- Contemporary Vs Modern Interior Design: A Breakdown of The StylesDocumento8 páginasContemporary Vs Modern Interior Design: A Breakdown of The StylesLesther AlmadronesAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 1 Theory of Modern ArchitectureDocumento33 páginasLecture 1 Theory of Modern Architecturerabia wahidAinda não há avaliações

- Durham Johnston School Music Department Ks3 Scheme of WorkDocumento10 páginasDurham Johnston School Music Department Ks3 Scheme of WorkRob WilliamsAinda não há avaliações

- Bold and MinimalistDocumento2 páginasBold and MinimalistmamamaAinda não há avaliações

- Design Movements TimelineDocumento15 páginasDesign Movements TimelineahgracioAinda não há avaliações

- Contemporary Art Techniques and Performance PracticesDocumento25 páginasContemporary Art Techniques and Performance PracticesEsther Quinones De FelipeAinda não há avaliações

- Per KirkebyDocumento11 páginasPer KirkebyAca Au Atalán100% (1)

- Diane Scillia - Less Is More or The Paradox of BoredomDocumento7 páginasDiane Scillia - Less Is More or The Paradox of BoredomFederico RequenaAinda não há avaliações

- New Art Deco StyleDocumento130 páginasNew Art Deco Stylevalysa0% (1)

- Anna Chave - Minimalism and The Rhetoric of PowerDocumento23 páginasAnna Chave - Minimalism and The Rhetoric of PowerEgor SofronovAinda não há avaliações

- 2 CPAR - MODULE 6 - 1st LONG TEST - q2Documento6 páginas2 CPAR - MODULE 6 - 1st LONG TEST - q2Criselda MantosAinda não há avaliações

- Verbal Ability Handout: (Introduction To VA) Ref: VAHO1002101Documento5 páginasVerbal Ability Handout: (Introduction To VA) Ref: VAHO1002101Me vAinda não há avaliações

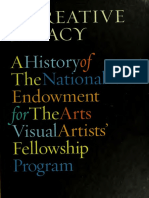

- A Creative Legacy/ A History of The National Endowment For The Arts Visual Artists' Fellowship ProgramDocumento264 páginasA Creative Legacy/ A History of The National Endowment For The Arts Visual Artists' Fellowship Programhandika saputraAinda não há avaliações

- Expo Guggenheim On Asian Art Influences 2009Documento10 páginasExpo Guggenheim On Asian Art Influences 2009Tsutsumi ChunagonAinda não há avaliações

- Bazin, An Early Late Modernist: Cato WittusenDocumento12 páginasBazin, An Early Late Modernist: Cato WittusenluisAinda não há avaliações

- Architecture and Design. Exhibition. Museum of Modern Art, New York CityDocumento22 páginasArchitecture and Design. Exhibition. Museum of Modern Art, New York CityEric J. HsuAinda não há avaliações

- MinimalismDocumento38 páginasMinimalismDawit ShankoAinda não há avaliações

- 데이비드 치퍼필드 건축에 나타난 맥락적 특성에 관한 연구 a Study on the Contextual Characteristics of David Chipperfield's ArchitectureDocumento12 páginas데이비드 치퍼필드 건축에 나타난 맥락적 특성에 관한 연구 a Study on the Contextual Characteristics of David Chipperfield's Architecturea01075374782Ainda não há avaliações

- Cpar Reviewer 1Documento4 páginasCpar Reviewer 1Ethan Matthew FernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Anthony GormleyDocumento5 páginasAnthony GormleyjlbAinda não há avaliações

- Art Beyond The Lens PDFDocumento178 páginasArt Beyond The Lens PDFCharles Joseph JacobAinda não há avaliações

- Molesworth House Work and Art WorkDocumento28 páginasMolesworth House Work and Art WorkLeah WolffAinda não há avaliações

- Musicophobia, or Sound Art and The Demands of Art TheoryDocumento20 páginasMusicophobia, or Sound Art and The Demands of Art TheoryricardariasAinda não há avaliações

- Intro To ArtDocumento31 páginasIntro To ArtSriLaxmi BulusuAinda não há avaliações

- Agnes Martin's Pursuit of Perfection Through DestructionDocumento8 páginasAgnes Martin's Pursuit of Perfection Through DestructionCarlosAlexandreRodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Concepts and Considerations in Architectural DesignDocumento22 páginasConcepts and Considerations in Architectural DesignKathleen Anne LandarAinda não há avaliações

- Design + Construction Magazine (July To September 2019)Documento100 páginasDesign + Construction Magazine (July To September 2019)Khuta JhayAinda não há avaliações

- 18,4M - What Are The Defining Characteristics of Bauhaus Design - QuoraDocumento1 página18,4M - What Are The Defining Characteristics of Bauhaus Design - QuoraConstantin FurtunaAinda não há avaliações

- Philippine Regional Arts TechniquesDocumento57 páginasPhilippine Regional Arts TechniquesHara Vienna ClivaAinda não há avaliações