Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Bura Woy 1983

Enviado por

Kairos QueridoDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Bura Woy 1983

Enviado por

Kairos QueridoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Between the Labor Process and the State: The Changing Face of Factory Regimes Under

Advanced Capitalism

Author(s): Michael Burawoy

Source: American Sociological Review, Vol. 48, No. 5 (Oct., 1983), pp. 587-605

Published by: American Sociological Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2094921 .

Accessed: 18/07/2013 10:35

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Sociological Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BETWEEN THE LABOR PROCESS AND THE STATE:

THE CHANGING FACE OF FACTORY REGIMES UNDER

ADVANCED CAPITALISM*

MICHAEL BuRAwoy

Universityof California-Berkeley

The paper develops the concept of politics of production through a double critique:

first, of recent literature on the organization of work for ignoring the political and

ideological regimes in production; and second, of recent theories of the state for

failing to root its interventions in the requirements of capitalist development. The

paper distinguishes three types of production politics: despotic, hegemonic, and

hegemonic despotic. The focus is on national variations of hegemonic regimes. The

empirical basis of the analysis is a comparison of two workshops, one in Manchester,

England, and the other in Chicago, with similar work organizations and situated in

similar market contexts. State supportfor those not employed and state regulation of

factory regimes explain the distinctive production politics not only in Britain and the

United States but also in Japan and Sweden. The different national configurations of

state intervention are themselves framed by the combined and uneven development

of capitalism on a world scale. Finally, consideration is given to the character of the

contemporary period, in which there emerges a new form of production

politics-hegemonic despotism-founded on the mobility of capital.

This paper has two targets and one arrow. Although organization theory has recently

The first target is the underpoliticizationof begun to pay attentionto micropolitics(Bums

production:theories of productionthat ignore et al., 1979; Clegg and Dunkerley, 1980; Zey-

its political moments as well as its determi- Ferrelland Aiken, 1981),there has been a fail-

nations by the state. The second target is the ure to theorize about, first, the difference be-

overpoliticizationof the state: theories of the tween the politics of productionand the politi-

state that stress its autonomy, dislocating it cal apparatusesof productionthat shape those

from its economic foundations. The arrow is politics; second, how both are limited by the

the notion of a politics of production which laborprocess on one side and marketforces on

aims to undo the compartmentalization of pro- the other; third, how both politics and appara-

ductionand politics by linkingthe organization

of work to the state. The view elaboratedin tics by its arena, so that state politics refers to strug-

this paper is that the process of production gles in the arena of the state, production politics to

contains political and ideological elements as struggles in the arena of the workplace, gender poli-

well as a purelyeconomic moment.Thatis, the tics to struggles in the family. For others, such as

process of production is not confined to the Stephens (1979:53-54), politics is always state poli-

labor process-to the social relations into tics and what distinguishes one form from another is

which men and women enter as they transform the goal. Thus, production politics aims to redistri-

raw materialsinto useful products with instru- bute control over the means of production, con-

ments of production. The process of produc- sumption politics focuses on the redistribution of the

means of consumption, and mobility politics in-

tion also includes political apparatuses which volves struggles to increase social mobility. These

reproducethose relationsof the labor process differences in the conception of politics are not

throughthe regulationof struggles.I call these merely terminological but reflect alternative under-

apparatusesthe factory regime and the associ- standings of the transition from capitalism to so-

ated struggles the politics of production or cialism. Whereas Stephens sees the transition as a

simply production politics.' gradual shift in state politics from consumption and

mobility issues to production issues, I see it in terms

* Direct all correspondence to: Michael Burawoy, of the transformation of production politics and state

Department of Sociology, University of California, politics through the reconstruction of production ap-

Berkeley, CA 94720. paratuses and state apparatuses. What Stephens re-

I should like to thank Steve Frenkel and three gards as the driving force behind the transition to

anonymous referees for their detailed comments. socialism-the 'changing balance of power in civil

Erik Wright has read more versions of this paper society," in effect the organization of labor into trade

than he cares to remember. As ever, I am grateful for unions-I regard as the consolidation of factory re-

his persistent encouragement and criticism. gimes which reproduce the capital-labor relationship

I Definitions are not innocent. I have defined poli- more efficiently.

American Sociological Review 1983, Vol. 48 (October:587-605) 587

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

588 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

tuses at the level of productiondifferfrom and capitalist caricatureof the social regulation

relate to state politics and state apparatuses. of the labourprocess which becomes neces-

The purposeof this paperis to specify the form sary on a large scale and in the employment

of politics at the levels both of productionand in common of instruments of labour, and

of the state and to examine their interrelation- especially of machinery. The overseer's

shipthrougha comparisonof an Englishand an book of penalties replacesthe slave-driver's

Americanfactory. The first part of the paper lash. All punishments naturally resolve

develops the concept of productionpolitics and themselves into fines and deductions from

the associated political apparatusesof produc- wages, and the law-givingtalent of the fac-

tion in the context of the dynamics of tory Lycurgus so arranges matters that a

capitalism and its labor process. The second violation of his laws is, if possible, more

part uses the two case studies to highlightna- profitableto him than the keeping of them.

tional variationin the form of productionpoli- (Marx, [1867] 1976:549-50)

tics. The thirdpartexplainsthose variationsin

terms of the relationshipbetween apparatuses Although Marx never conceptualizes the idea

of productionand apparatusesof the state, a of political apparatusesof production,he is in

relationshipwhich is decisively determinedby fact describinga particulartype of factory re-

the combined and uneven developmentof the gime which I will call marketdespotism. Here

capital-laborrelationship. The final part con- the despotic regulationof the labor process is

siders the emergence of new forms of produc- constituted by the economic whip of the

tion politics in the latest phase of capitalist market. The dependence of workers on cash

development. earningsis inscribed in their subordinationto

the factory Lycurgus.

FROM MARKET DESPOTISMTO Marx does not recognize factory regimes as

HEGEMONICREGIMES analyticallydistinct from the labor process be-

cause he sees market despotism as the only

The Marxisttraditionoffers the most sustained mode of labor process regulationcompatible

attemptto understandthe developmentof pro- with modern industry and the pressure for

duction within a systemic view of profits.In fact, marketdespotismis a relatively

capitalism-that is, a view which explores the rareform of factory regimewhose existence is

dynamics and tendencies of capitalismas well dependenton three historicallyspecific condi-

as the conditions of its reproduction.Produc- tions: (1) Workers have no other means of

tion is at the core of both the perpetuationand livelihood than throughthe sale of their labor

the demise of capitalism.The act of production power for a wage. (2) The labor process is

is simultaneouslyan act of reproduction. At subjectto fragmentationand mechanizationso

the same time that they produceuseful things, that skill and specialized knowledge can no

workers produce the basis of their own exis- longer be a basis of power. The systematic

tence as well as that of capital. The exchange separationof mentaland manuallaborand the

value added through cooperative labor is di- reduction of workers to appendages of ma-

vided between the wage equivalent, which be- chines strip workers of the capacity to resist

comes the means of the reproductionof labor arbitrarycoercion. (3) Impelled by competi-

power so that the workercan turn up the next tion, capitalists continuallytransformproduc-

day, and surplus value, the source of profit tion throughthe extension of the workingday,

which makes it possible for the capitalist to intensificationof work and the introductionof

exist as such and thus employ the laborer. new machinery.Anarchyin the marketleads to

How is it that the labor power-the capacity despotism in the factory.

to work-is translated into sufficient labor- If history has more or less upheld Marx's

application of effort-so as to provide both analysis of competitive capitalism, it has not

wages and profit? Marx answers, through upheldthe identificationof the demise of com-

coercion. In his analysis, the extractionof ef- petitive capitalism with the demise of

fort occurs through a despotic regime of pro- capitalismper se. What Marxperceivedas the

duction politics. embryonicforms of socialism, in particularthe

socializationof productionthroughconcentra-

In the factory code, the capitalistformulates tion, centralizationand mechanization,in fact

his autocraticpower over his workerslike a laid the basis of a new type of capitalism,

private legislator, and purely as an emana- monopoly capitalism. The hallmark of

tion of his own will, unaccompanied by twentieth-centuryMarxismhas been the char-

either that division of responsibilityother- acterizationof this new form of capitalism-its

wise so much approved of by the politics, its economics, and its culture. Curi-

bourgeoisie, or the still more approved rep- ously, it is only in the last decade that Marxists

resentativesystem. This code is merely the have begun to reconsider Marx's analysis of

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FACTORYREGIMES UNDER ADVANCED CAPITALISM 589

the labor process, in particularits transforma- simple control, as Edwards maintains. Thus,

tion over time. Littler(1982)and Clawson(1980)underlinethe

These studies have generally dwealt on his- importanceof subcontracting,both inside and

toricizing the second and third conditions of outside the firm, as an obstacle to direct con-

marketdespotism: deskillingand perfect com- trol by the employer. Nor can the period of

petitionamongfirms. Braverman(1974)argues advancedcapitalismbe reducedto the consoli-

that deskilling really established itself only in dation of deskilling. New skills are continually

the periodof monopoly capitalismwhen firms created and do not disappear as rapidly as

were sufficiently powerful to crush the resist- Bravermansuggests (Wrightand Singelmann,

ance of craft workers. Friedman's (1977) 1983).Finally, Edwardsquite explicitly recog-

analysis of changes in the laborprocess in En- nizes that each successive period contains and

gland counters Braverman's unilinear de- actively reproduces forms of control originat-

gradation of work by underlining the im- ing in previous periods. All these works point

portanceof resistance in shapingtwo manage- to the distinction between the labor process

rial strategies: direct control and responsible conceived of as a particularorganization of

autonomy. Direct control corresponds to tasks and the political apparatusesof produc-

Braverman'sprocess of deskilling,whereasre- tion conceived of as its mode of regulation.In

sponsible autonomy attaches workers to the contrastto Braverman,who ignores the politi-

interestsof capitalby allowingthem limitedjob cal apparatusesof production, and Edwards,

control, a limited unity of conception and Friedman, Littler and Clawson, who collapse

execution. In the early period of capitalism, them into the labor process, I treat them as

responsibleautonomy was a legacy of the past analytically distinct from and causally inde-

and took the form of craft control, whereas pendentof the labor process. Moreover, these

under monopoly capitalism it is a self- political apparatusesof production provide a

conscious managerial strategy to preempt basis for the periodizationof capitalistproduc-

worker resistance. tion.

In an even more far-reachingreconstruction Whilenot denying the importanceof histori-

of Braverman'sanalysis, Edwards(1979)iden- cally rooting Marx's second and third condi-

tifies the emergence of three historically suc- tions of market despotism-competition

cessive forms of control: simple, technical and amongfirmsand the expropriationof skill-for

bureaucratic.In the nineteenthcentury, firms an understandingof the transformationof labor

were generallysmall and marketscompetitive, controls, I want to dwell on the first condition,

so that managementexercised arbitrary,per- the dependenceof workerson the sale of their

sonalistic dominationover workers. With the labor power. In this connection we must ex-

twentieth-centurygrowth of large-scaleindus- amine two forms of state intervention which

try, simple control gave way to new forms. breakthe ties bindingthe reproductionof labor

After a series of unsuccessful experiments, power to productiveactivity in the workplace.

capital sought to regulate work through the First, social insurance legislation guarantees

drive system and by incorporatingcontrol into the reproductionof labor power at a certain

technology, epitomized by the assembly line. minimal level independent of participationin

This mode of control generated its own forms production. Moreover, such insurance effec-

of struggle and, after World War Two, gave tively establishes a minimumwage (although

way to bureaucraticregulation,in which rules this may also be legislatively enforced), con-

are used to define and evaluate work tasks and strainingthe use of payment by results. Piece

govern the applicationof sanctions. Although rates can no longer be arbitrarilycut to extract

each period generates its own prototypical ever greatereffort for the same wage. Second,

formof control, all neverthelesscoexist within the state directly establishes limits on those

the contemporaryU.S. economy as reflections methods of managerial domination which

of various market relations. In a more recent exploit the dependence of workers on wages.

formulation,Gordonet al. (1982)have situated Compulsorytradeunionrecognition,grievance

the development of the three forms of labor machinery and collective bargainingprotect

control in three social structuresof accumula- workersfrom arbitraryfiring, fining and wage

tion correspondingto long swings in the U.S. reductions and thus further enhance the au-

economy. tonomy of the reproductionof labor power.

While all these accounts add a great deal to The repeal of Mastersand Servantslaws gives

our understandingof the transformationof labor the right to quit and so underminesem-

work organizationand its regulation,they are ployers' attemptsto tie domestic life to factory

unsatisfactory as periodizations of capitalist life.

production.We know that the period of early Although many have pointed to the devel-

capitalism was neither the haven of the craft opment of these social and political rights,few

worker,as Bravermanimplies, nor confined to have explored their ramificationsfor the regu-

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

590 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

lation of production.Now managementcan no hegemonic regimes, the decisive basis for pe-

longer rely entirely on the economic whip of riodizationremainsthe unity/separationof the

the market. Nor can it impose an arbitrary reproductionof laborpower and capitalistpro-

despotism. Workers must be persuaded to duction.

cooperate with management. Their interests Exceptions to this demarcation further il-

must be coordinatedwith those of capital. The luminate it. Thus, Californiaagribusiness of-

despotic regimes of early capitalism,in which fers examples of monopoly industrywith des-

coercion prevails over consent, must be re- potic control. There are two explanations for

placed withhegemonic regimes, in which con- this anomaly. First, agriculture has been

sent prevails, althoughnever to the exclusion exempt from national labor legislation so that

of coercion.Not only is the applicationof coer- farm workers are not protectedfrom the arbi-

cion circumscribedand regularized,but the in- trarydespotismof managers.Second, workers

fliction of discipline and punishmentitself be- are frequently not citizens and often illegal

comes the object of consent. Thegeneric char- immigrants,so they are unable to draw any

acter of the factory regime is, therefore, de- social insurance and must constantly live in

terminedindependentlyof the formof the labor fear of apprehension.In effect, Californiaag-

process and competitive pressures among ribusiness has successfully established a re-

firms. It is determinedby the dependence of lationship to the state akin to that between

the livelihoodof workerson wage employment industry and state under early capitalism in

and the dependence of the latter on perfor- order to enforce despotic regimes (Thomas,

mance in the place of work. State social insur- 1983;Wells, 1983). Urban enterprise zones-

ance reduces the first dependence, while labor selected geographicalareas in which capital is

legislation reduces the second. encouraged to invest by lowering taxes and

While despotic regimes are based on the relaxing protective legislation for labor-are

unity of the reproductionof labor power and similarattempts to restore nineteenth-century

the process of production,and hegemonic re- marketdespotism. However, they remain ex-

gimes on a limitedbut definiteseparationof the ceptional.

two, their specific charactervaries with forms As others have argued(Piven and Cloward,

of labor process and competitionamong firms 1982; Skocpol and Ikenberry, 1982), attempts

as well as with forms of state intervention. to dismantle what exists of the welfare state

Thus, the form of despotic regime varies can achieve only limitedsuccess. More signifi-

among countries accordingto patternsof pro- cant for the developmentof factory regimes is

letarianization,so that where workers retain the vulnerability of collective labor, in the

ties to subsistence existence various pater- contemporaryperiod, to the national and in-

nalistic regimes with a more or less coercive ternationalmobilityof capital, leadingto a new

characteremerge to create additionalbases of despotism built on the foundations of the

dependence of workers on their employers hegemonic regime. That is, workers face the

(Burawoy, 1982). Hegemonic regimes also threatof losing theirjobs not as individualsbut

differ from country to country based on the as a resultof threatsto the viabilityof the firm.

extent of state-provided social insurance This enables management to turn the

schemes and the characterof state regulation hegemonic regime against workers, relying on

of factory regimes. Furthermore,the factors its mechanisms of coordinating interests to

highlighted by Braverman, Friedman and command consent to sacrifices. Concession

Edwards-skill, technology, competition bargainingand qualityof worklifeprogramsare

among firms, and resistance-all give rise to two faces of this hegemonic despotism.

variations in regimes within countries. Thus, The periodization just sketched, from

variationsin deskillingand competitionamong market despotism to hegemonic regimes to

firms created the conditions for very different hegemonic despotism, is rooted in the

despotic regimes in nineteenth-centuryLanca- dynamics of capitalism. In the first period the

shire cotton mills: marketdespotism, patriarc- searchfor profitled capital to intensifyexploi-

hal despotism, and paternalistic despotism tation with the assistance of despotic regimes.

(Burawoy, 1982). Under advanced capitalism This gave rise to crises of underconsumption

the form of hegemonic regime also varies ac- and resistancefrom workers,and resolutionof

cording to the sector of the economy. In the these conflicts could be achieved only at the

competitive sector we find the balance be- level of collective capital-that is, through

tween consent and coercion furthertowardthe state intervention. This took two forms-the

latter than in the monopoly sector, although constitutionof the social wage and the restric-

where workers retain considerable control tion of managerialdiscretion-which, as we

over the labor process we find forms of craft have argued, gave rise to the hegemonic re-

administration.Notwithstandingthe important gime. The necessity of such state intervention

variationsamong despotic regimes and among is given by the logic of the development of

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FACTORY REGIMES UNDER ADVANCED CAPITALISM 591

capitalism.But the mechanismsthroughwhich from smaller firms. The other enterprise, Al-

the state comes to do what is "necessary"vary lied, was the engine division of a multinational

over time and from country to country. Here corporation whose primary sales ventures

we draw on an arrayof explanationsthat have were in agriculturaland construction equip-

figuredprominentlyin recent debatesaboutthe ment. For ten months, in 1974-1975, I worked

nature of the capitalist state: the state as an -in the small parts department of this South

instrument of an enlightened fraction of the Chicago plant as a miscellaneous machine

dominant classes, the state as subject to the operator. Donald Roy (1952, 1953, 1954) had

interests of "state managers,"the state as re- studied the same plant thirty years earlier,

sponsive to struggles both within and outside when it was a largejobbing shop, before it was

itself. There is, of course, nothinginevitableor taken over by Allied. It was then known as

inexorable about these state interventions; Geer.

nothingguaranteesthe success or even the ac-

tivation of the appropriatemechanisms.Thus, The Labor Process

althoughwe have theories of the conditionsfor

the reproductionof capitalism in its various Allied's machine shop was much the same as

phases, and therefore of the corresponding any other, with its assortment of mills, drills

necessary state interventions,we have only ad and lathes, each operated by a single worker

hoc accounts of the actual, specific and con- who depended on the services of a variety of

crete interventions. auxiliaryworkers:set-up men, who mighthelp

Nevertheless, the form and timing of "set up" the machinesfor each new "job";crib

capitalist development frame the nature of attendants, who controlled the distributionof

state interventionas well as shape the form of fixtures and tools kept in the crib; the forklift

factory regime. As will be discussed below we "trucker," who transported stock and un-

can begin to locate the rapidityandunevenness finished "pieces" from place to place in large

of state interventions in the context of the tubs; the time clerk, who would punch oper-

combined and uneven development of ators in on new jobs and out on completed

capitalismat an internationallevel. Moreover, ones; the schedulingman, who was responsible

in the contemporaryperiod the logic of capital for directing the distribution of work and

accumulationon a world scale determinesthat chasing materialsaround the department;and

state interventionbecomes less relevantfor the the inspectors, who would have to "okay" the

determinationof changes and variationsin the first piece before operators could "get going"

form of production politics. This is the argu- and turn out the work. Finally, the foreman

ment of the paper's final section. The very would oversee operations, coordinating and

success of the hegemonic regime in constrain- facilitatingproductionwhere necessary: sign-

ing managementand establishing a new con- ing double red cards, which guaranteeda basic

sumptionnormleads to a crisis of profitability. "anticipated piece rate" when operators,

As a result, managementattemptsto bypass or throughno fault of their own, were unable to

underminethe stricturesof the hegemonic re- get ahead, and negotiatingwith auxiliarywork-

gime while embracing those of its features ers on behalf of the operators.

which foster worker cooperation. The laborprocess at Jay's was similarin that

workers controlled their own instruments of

productionand were dependenton the services

FACTORYPOLITICSAT JAY'S of auxiliary workers. In the erection section,

AND ALLIED operators used hand tools such as soldering

To highlightboth the generic characterof the irons, wire clippers and spanners. There was

hegemonic regime and its different specific no mass productionsequence: each electrical

forms, we will compare two workshops with assembly was completed by an erector, or by

similarlabor processes and systems of remun- two and sometimes even three "working

erationsituatedwithin similarmarketcontexts mates" (Lupton, 1963:104-105). There were

but differentnationalcontexts. The first com- fewer auxiliary workers than at Allied: the

pany, Jay's, is Britishand was studiedby Tom floor controller ("scheduling man"), the in-

Luptonin 1956. It was a Manchesterelectrical spector, the charge hand ("set-up man"), the

engineeringcompany with divisions overseas. store-keeper ("crib attendant") and the time

Lupton was a participant observer for six clerk. There was less intrasectiontension and

months in a department which erected conflict than at Geer and Allied, which sprang

transformersfor commercial use. Jay's was fromthe dependenceof piece-rateoperatorson

partof the monopolysector of Britishindustry, day-rateauxiliaryworkers. The lateralconflict

dominatedby such giants as Vicker's. It was a at Jay's was instead between sections over de-

member of an employers' association which livery of the rightparts at the righttime and in

engagedin price fixing and barredcompetition the right quantity. Thus, the erectors at Jay's

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

592 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

formed a relatively cohesive group based on Making Out

their antagonismtoward and dependence on

other sections and departments. The similarityin systems of remunerationand

labor process at the two factories gave rise to

similaroperatorstrategies. At both Allied and

Jay's piecework was constituted as a game,

The System of Remuneration called "making out" in both plants, in which

The systems of remunerationin the two shops operators set themselves certain percentage

were also organized on similar principles. output targets. Shop-floor activities were

Operatorsat Allied were paid according to a dominated by the concerns of making out;

piece-rate system which worked as follows: shop-floor culture was couched in the suc-

each job had a rate attached to it by the cesses and failures of playingthe game. It was

methods department, which stipulated the in these terms that operators would evaluate

numberof pieces to be producedper hour-the each other. The activities of the rate fixer and

"100o" bench mark.Operatorswere expected the distributionof "stinkers" (jobs with diffi-

to performat 125%,the "anticipatedrate" de- cult or "tight" rates) or "gravy" work (jobs

fined in the contract as productionby a "nor- with easy or "loose" rates)were the subjectsof

mal experiencedoperatorworkingat incentive eternal animationand dispute.

gait." Producingat 125%would earn the oper- The rules of makingout were similarin both

ator an extra 25% of the base earningsestab- shops. Workersengaged in the same forms of

lishedfor the particularlaborgrade. In termsof "restrictionof output." That is, there was a

total earnings, producingat 125%brought in jointly regulatedupper limit on the amount of

about 15%more than did producingat 100o. work to be "handed in" (Allied) or "booked"

Whenoperatorsfailed to makeout at the 100% (Jay's), viz. 140Woand 190Wo,respectively.

level, they nevertheless received earningscor- Higherpercentagesinvited the rate fixer to cut

respondingto 100%.An operator'stotal earn- the rates. Holding back work which was com-

ings were thus composed of base earnings;an pleted at higher than these ceilings was called

incentive bonus, based on percentage output; "banking"(Jay's)or "buildinga kitty"(Allied).

override, which was a fixed amount for each This practice enabled workers to make up for

labor grade; a shift differential;and a cost of earningslost on badjobs by handingin pieces

living allowance. saved from easy jobs. However, such "cross-

The weekly wage packet at Jay's was made booking" ("fiddling"at Jay's, "chiselling" at

up of three items. First, there was the hourly Allied) was easier and morelegitimateat Jay's.

rate or guaranteed minimum wage-either a Allied had clocks for punchingon and off jobs,

"timerate"for day workor a "pieceworkrate" makingcross-booking more difficult, whereas

for piecework. Second, there was a bonus, there was no such constraint at Jay's.

which was itself composed of threeelements:a Moreover,cooperationfrom auxiliaryworkers

bonus of 45%on the piece rate for time spent in making out and fiddling by pieceworkers

waiting for materials or inspection or wasted was more pronouncedat Jay's.

on defective equipment;a negotiatedpercent- This form of output restriction, known as

age bonus for jobs that did not have a rate quotarestriction,in which workerscollectively

(known as "covered jobs," as at Allied); and enforce an upper limit on the amount of work

the piecework bonus itself. The third item of to be handed in, affects the second form of

the wage packet was a group productivity restriction."Goldbricking"occurs when oper-

bonus based on the outputof the entire section ators find making the rate for a certain job

for the week. impossibleor not worth the effort. They take it

The piecework bonus was derived as fol- easy, content to earn the guaranteedminimum.

lows: each job was given a rate in terms of Goldbrickingwas more common at Allied than

"allowed time." A job completed in the at Jay's, for two reasons. First, as already

allowed time obtaineda bonus of 271/2% of the stated, it was much easier to cross-book at

rate. Rate fixers were supposed to set the Jay's, and it was therefore more likely that a

allowed times so that the erectors could, with bad performanceon a lousy job could be made

little experience, earn an 80o bonus. Workers up with time saved on easierjobs. Second, the

were content when they could produce at percentages earned on piecework were much

190%.Thus, the anticipatedrate of 125%at higher at Jay's, and the achievement of 100lo

Allied correspondedto the 180%o rate at Jay's. was virtually automatic. Accordingly, the

In monetaryterms, then, the expected earnings bimodalpattern,observed by Roy at Geer and

frompieceworkrelative to base rates were sig- still discernible at Allied, in which output

nificantlyhigherat Jay's than at Allied, where levels clustered around both upper and lower

the 140%0output was the collectively under- limits, could not be found at Jay's. These dif-

stood upper limit. ferences suggestthat workershad morecontrol

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FACTORY REGIMES UNDER ADVANCED CAPITALISM 593

over the laborprocess and thereforemore bar- lied the balanceof class forces was inscribedin

gainingpower with managementat Jay's than ruleswhose form was stablebut whose content

at Allied. was determined in three-year collective

agreements negotiated between management

and union. For the durationof the contract,all

Rate Fixing

partiesagreedto abide by the constraintsit set

In broadoutline, there are close resemblances on the realization of interests. Strikes broke

in the patterns of conflict and cooperation as out when the contract under negotiation was

they are playedout in the two shops. However, unacceptableto the rankand file. At Jay's, by

the continual bargainingand renegotiationat contrast, the balance of class forces was con-

Jay's contrast with the broad adhesion to a tinuallyrenegotiatedon the shop floor. "Unof-

common set of proceduralrules at Allied. This ficial" short strikes were part and parcel of

is particularlyclear in the relationshipbetween industriallife. In the one, the political appara-

rate fixers and operators.The Allied rate fixer tuses of productionare severed from the labor

was an "industrial engineer" who retired to process; in the other, the two are almost indis-

distant offices. Rather than stalkingthe aisles tinguishable.The differences between the two

in pursuitof loose rates, as had been the cus- patternscan be clearly discerned in the opera-

tom at Geer, he had become more concerned tion of the "internallabor market."

with changes in the organizationof work, in-

troducingnew machines and computingrates The Internal Labor Market

on his pocket computer. At Jay's, where

piecework earnings were a more important We speak of an internallabormarketwhen the

element of the wage packet, the rate fixer was distribution of employees within the firm is

still the time-and-motionman with stopwatch administeredthrougha set of rules defined in-

in hand. His presence, as at Geer, created a dependently of the external labor market. At

"spectacle"to which all workersin the section Allied it worked as follows: when a vacancy

were drawn. occurred in a department, any worker from

But the air of tyranny that pervaded that departmentcould "bid" for the job. The

Geer-the sly attempts of time-study men to bidder with the greatest seniority usually re-

clock jobs while they had their backs to the ceived the job, and his old job became vacant.

operators-was absent at Jay's. First, unlike If no one was interested in the opening, or if

both Geer and Allied, operatorsat Jay's had to management deemed the applicants unqual-

agree to new rates before they were intro- ified, the job would be posted plantwide. If

duced. Second, the conflict which broughtthe there were still no acceptable bids, someone

rate fixer and operatorinto oppositionobeyed would be hiredfrom outside, from the external

certain principles of fair play which both ob- labormarket.Generally,then, new employees

served. The shop steward in particularmain- enteredon those jobs that no one else wanted,

tained a constant vigilance to prevent any usually the speed drills. Similarly, workers

subterfugeby the rate fixer or hastiness by the who were being laid off could "bump" other

operator. On those rare occasions when in- employees whose jobs they could performand

dustrial engineers came down from their of- who had less seniority. An internal labor

fices at Allied, shop stewards were usually far marketnot only presupposessome criteriafor

fromthe scene. They shruggedtheirshoulders, selecting amongbids-in this case a heavy em-

denyingany responsibilityfor ratebusters who phasis on seniority-but also some hierarchy

would consistently turn in more than 140%o. of jobs based on basic earningsand looseness

Bargaining over "custom and practice" of piece rates. Otherwiseworkerswould be in

(Brown, 1972)rather than consent to bureau- constantmotion. Efficiency in the organization

cratically administeredrules shaped produc- of the plantdependson a certainstabilityofjob

tion politics at Jay's. Thus, jobs without rates tenure, particularlyon the more sophisticated

became the subject of intense disputationbe- machines whose operation requires a little

tween foreman and worker, whereas at Allied more skill.

such jobs were automaticallypaid at the "an- The internal labor market has a number of

ticipated rate" of 125%. In the allocation of importantconsequences. First, the possessive

work, operators in Jay's transformersection individualism associated with the external

were in a much stronger position to bargain labor marketis now importedinto the factory.

with the foreman than were the operators at The system of bidding and bumping elevates

Allied. Indeed, this was the basis of much of the individual interest at the expense of the

the factionalismwithin the section, intensified collective interest. Grievances related to the

by the absence of well-definedprocedures. job can be resolved by the employee's simply

These differences exemplify a more general biddingon anotherjob. Second, the possibility

distinctionbetweenthe two workshops.At Al- of biddingoff a job gives the workera certain

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

594 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

autonomy vis-a-vis first-line supervision. If a tempts by specific groups to maintaintheir po-

foremanbegins to give trouble,an operatorcan sition relative to other groups rather than an

simplybid off thejob into anothersection. The implacable hostility to management.Techno-

possibility and reality of voluntary transfer logical innovations that upset customary dif-

deter foremen from exercising arbitrarycom- ferentialsare bitterly resisted by those whose

mand since turnover would lead to a fall in positionsare undermined.At Jay's, production

productivity and quality. The internal labor politics revolved more aroundnotions of social

marketis therefore much more effective than justice and fairness ratherthan the pursuit of

any human relations program in producing individualinterest throughthe manipulationof

supervisors sensitive to the personalities of established bureaucratic rules. These dif-

their subordinates. Indeed, the rise of the ferences are reflected more generally in the

humanrelationsprogramcan be seen as a mere system of bargaining.

rationalizationor reflection of the underlying

changes in the apparatusesof productionsince Systems of Bargaining

World War Two.

The third consequence of the internallabor Formally, the internal labor market at Allied

market is the coordinationof the interests of was an administrativedevice for distributing

workers and management. Because seniority employees into jobs on the basis of seniority.

dictated the distributionof rewards-not only By promotingindividualismand enlargingthe

the best jobs but vacation pay, supplementary arena of worker autonomy within definite

unemploymentbenefits, medicalcare and pen- limits, it was also a mechanismfor regulating

sions as well-the longer a person remainedat relations between workers and management.

Allied, the more costly it was to move to an- Its effects were similar to two other appara-

other firm and the more he or she identified tuses of production, viz. the grievance ma-

with the interests of the firm. From manage- chinery and collective bargaining.Here, too,

ment's standpoint, this involved not only bureaucratic regulations dominated. Union

greatercommitmentto the generationof profit contracts were renegotiated by the local and

but also reduced uncertainties induced by the managementof the engine division every

changes in the external labor market. Thus, three years. Once the contract was signed, the

voluntary separations were necessarily re- union became its watchdog. Processinggriev-

duced, particularlyamongthe more senior and ances was regularizedinto a series of stages

therefore more "skilled" employees. And which broughtin successively higherechelons

when layoffs occurred, the system of sup- of managementand union. Grievances would

plementary unemployment benefits retained always be referred to the contract. Workers

hold of the same labor pool for sometimes as would approachthe shop steward as a guard

long as a year. rather than an incendiary. The shop steward

At Jay's the distinctionbetween internaland would pull out the contract and pronounceon

external labor marketswas harderto discern. its interpretation.The contractwas sacrosanct:

There was no systematicjob hierarchy,such a it circumscribedthe terrainof struggle.

central feature of the organizationof work at Productionpolitics at Jay's followed a very

Allied. All pieceworkoperatorsin the erecting different course. There was no bureaucratic

section, except those undergoing training, apparatusto confine struggles within definite

were on the same piece or time wage. There limits. There the "collective bargain"was a

was no system of biddingon new jobs and the fluid agreement subject to spontaneous abro-

issue of transfers never seemed to come up. gation and continualrenegotiationon the shop

Opposition to managementcould not be re- floor. "Customand practice"providedthe ter-

solved by "bidding off' the job. Grievances rain of struggle, and diverse principles of

had to be lived with or fought out or, as a last legitimationwere mobilized to pursue strug-

resort, workers could leave the firm. Thus, in gles. Rules had not the stability, the authority

contrast to Allied's organizationof rights and nor the specificity they had achieved at Allied.

obligations in accordance with seniority, a The engineeringindustry,of which Jay's was a

radicalegalitarianismpervadedin the relations member, did have a regularizedmachineryfor

amongworkers.Factionalsquabbleswithinthe handling grievances, but there was no clear

section frequently arose from the foreman's demarcation between disputes over "rights"

supposedlydiscriminatorydistributionof work and disputes over "interests"-that is, be-

(Lupton, 1963:142,163).As others have argued tween issues pursuedas grievances and issues

(Hyman and Brough, 1975; Maitland, 1983), which were part of collective bargaining.The

English workers are acutely aware of dif- results are clear. Whereas the grievance ma-

ferentialsin pay and workingconditions. Con- chineryat Allieddampenedcollective struggles

flict on the shop floor often arises from at- by constituting workers as individuals with

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FACTORY REGIMES UNDER ADVANCED CAPITALISM 595

specific rights and obligations, grievances at representation,union dues check-off systems,

Jay'swere the precipitantof sectionalstruggles and the greater number of paid officials en-

which brought managementand workers into joyed by unions in the United States contribute

continualcollision (Maitland, 1983). to a more complacent local. The complacency

We can begin to interpret the differences dovetails well with the union's role as night

between the two firms in termsof the structure watchmanover the collective agreement.

of relationsbetween managementand union in Not only do differentBritishunionscompete

the two countries. At Allied (and more gener- for the allegiance of the same workers, but a

ally in the organizedsectors of U.S. industry)a geographicalregionratherthanthe plantforms

single union (in this case the United Steelwor- the basic organizationalunit. Such interunion

kers of America)had exclusive rightsof repre- rivalryand the separationof the organization

sentation at the level of the plant. It was a base from the shop floor lead to shop steward

union shop, so that after fifty days' probation militancy. This is further encouraged by the

all employees covered by the contract had to limited financial ability of the branch to pay

join the union. Collectivebargainingtook place union officials and by the union's need to col-

at the plant level, although the issues were lect its own dues. Finally, unionrivalryand the

usuallyborrowedfromnegotiationswhichtook legacy of a powerful craft unionism in Britain

place between the union and the largestcorpo- continue to lead to demarcationdisputes and

rations, such as the United States Steel strugglesto protect wage differentials,thereby

Corporation-a system known as patternbar- threatening collective agreements. In the

gaining. Rank and file had the opportunityto United States the struggles for union repre-

ratify the agreement struck between manage- sentation in a given plant-jurisdictional

mentand unionbut, once signed, the collective disputes-are no longer as importantas they

bargainwas legally bindingon both sides of the were when industrialunionism was in its ex-

industry. pansionaryphase.

At Jay's, and more generally in England, a A second set of reasons for the contrasting

differentsituationpertained.Formalcollective status of "collective bargains" in the two

bargainingtook place at the national or re- countries revolves around the relationship

gional level of industry,not at the level of the between apparatusesof productionand appa-

plant. It established minimalconditionsof em- ratuses of the state. Thus, in Englandthe col-

ployment. Shop-floorbargainingwas therefore lective bargainis not legally binding. It is a

the adjustmentof the industry-wideagreement voluntary agreement of no fixed duration

to the local situation,which also explains why which can be broken by either side. Strikes

the wage system was much more complicated may be "unconstitutional"-in violation of the

at Jay's thanat Allied, despite the latter'sgrad- collective agreement-or "unofficial"-in op-

uated job hierarchy (Lupton, 1963:137-38). position to union leadership-but only under

The adjustmentto the conditions of the par- exceptional circumstances are they illegal. In

ticular firm or workshop explains why it is the United States, on the otherhand, collective

necessary to amend national and regional bargains are legally binding and no-strike

agreements,but why are "collective bargains" clauses can lead to legal action against the

not struck first at the plant level? union. Unlike its Britishcounterpart,the U.S.

One set of explanationsfor this concerns the trade union is a legal entity subject to legal

differences in union organization and repre- provisions:it is legally responsiblefor the ac-

sentationin the two countries. Until recently, tions of its members. The law is one mode

only a few British industries, such as coal throughwhich the state can shape factory poli-

mining, have had exclusive representationat tics: it is one expression of state regulationof

the plant level. At Jay's, for example, two factory regimes.

unions, the electrical Trades Union and the

National Union of General and Municipal

workers, competed for the allegiance of the PRODUCTIONAPPARATUSESAND

workers in the transformersection (Lupton, STATE APPARATUSES

1963:115). In the United States not only is We have now dealt with our first target by

there exclusive representation,guaranteedby showing that factory regimes both vary inde-

a union shop, but disaffiliationof a local from pendently of the labor process and effect

its internationalis notoriouslydifficult (Herd- shop-floor struggles. But how do we explain

ing, 1972:267-70). Attempts by some Allied the differencesbetween the hegemonicregime

workers hostile to the United Steelworkersto at Jay's based on fractionalbargainingand the

change affiliationto the United Auto Workers one at Allied based on bureaucraticrules? As

were effectively smotheredby union and man- we have controlled for labor process and

agement. Furthermore,the exclusive rights of market competition, these cannot be the

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

596 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

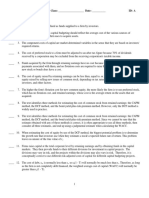

source of the differences. A more promising production apparatuses. The following table

variableis the form and content of state inter- sums up the different patterns. These, of

vention. Confirmationthat some such national

variable is at work comes from the industrial State Supportfor

relationsliteraturedealingwith the postwarpe- the Reproduction

riod which suggests that fractionalbargaining of Labor Power

has been typical of the manufacturingindustry HIGH LOW

in England(Hyman, 1975;Kahn-Freund,1977; HIGH Sweden United

Clegg, 1979; Maitland, 1983),just as bureau- Direct State States

cratic procedureshave been typical of the cor- Regulationof

porate sector of the United States (Strauss, Factory Regime

1962; Derber et al., 1965; Herding, 1972; LOW England Japan

Brody, 1979:chapter 5).

What is it about state interventions that course, representonly broadnationalpatterns.

creates distinctive apparatuses?The same two Withineach country, there may be wide varia-

interventionsthat served to distinguish early tions in the relationshipof productionappara-

capitalismfrom advancedcapitalismalso serve tuses to the state. State interventionsgive rise

to distinguish among advanced capitalist to only the generic form of factory regime: its

societies. The first type of state intervention specific forms are also determinedby the labor

separatesthe reproductionof laborpowerfrom process and marketforces.

the process of production by establishing But what determinesthe form of state inter-

minimallevels of welfare irrespectiveof work vention? We must now withdraw our arrow

performance.In the United States workersare fromthe first targetand point it in the opposite

more dependenton the firmfor social benefits, direction, at the second target:theories of the

althoughthese may be negligiblein the unorga- state that explain its interventionsin terms of

nized sectors, than they are in England,where its own structure,divorcedfrom the economic

state social insurance is more extensive. The context in which it operates. Nor is it sufficient

second type of state interventiondirectly reg- to recognize the importance of external eco-

ulates production apparatuses. As we inti- nomic forces by examiningtheir "presence"in

matedat the end of the last section, in England the state, as in corporatist bargaining

the state abstains from the regulationof pro- structures or the struggles of parties, trade

duction apparatuses whereas in the United unions, employers' associations, etc., at the

States the state sets limits on the form of pro- national level. As Panitch (1981) has argued,

duction apparatuses,at least in the corporate the effects of class forces cannot be reducedto

sector. their mode of "internalization"in state appa-

Our two case studies demonstratethe exis- ratuses. State politics do not hang from the

tence of differenthegemonicregimesand point clouds; they rise from the ground, and when

to the state as a key explanatoryvariable, but the ground trembles, so do they. In short,

they present a static view and, moreover, one while productionpolitics may not have a di-

in which the relevantcontexts appearonly in- rectly observable presence in the state, they

directly. We must now move away from Allied neverthelessset limits on and precipitateinter-

and Jay's themselves and examine state inter- ventions of the state. Thus, for example, the

ventions in their own right-both their form strike waves in the United States during the

and their origins. We must develop a dynamic 1930s and in Sweden, France, Italy, and En-

perspective, situatingthe two factories in their glandin the late 1960sand early 1970sall led to

respective political and economic contexts attempts by the state to reconstruct factory

througha broader historical and comparative apparatuses.

analysis. To do this we must first complete the Accordingly,just as the state sets limits on

picture of state interventions by adding two factory apparatuses,so the latter set limits on

morenationalconfigurationsof state regulation

of factory regimes and state support for the 2 Although the focus of this paper is on differences

reproductionof labor power. Ourthirdcombi- between societies, the existence of variations within

nation is representedhere by Sweden, where societies cannot be overemphasized. Thus, in the

extensive safeguards against unemploy- United States the marked difference in factory re-

ment-an active manpower policy and a gimes between sectors is a product not merely of

market factors but of different relations to the state

well-developed welfare system-coexist with defined by Taft-Hartley provisions, exclusion of up

substantial regulation of factory regimes. to half the labor force from the NLRB, state right-

In Japan(ourfourthcombination),on the other to-work rules which outlaw union shops, free speech

hand, the state offers little by way of social amendments favoring employer interference in or-

insurance, this being left to the firm, and is ganizing campaigns, disenfranchisement of strikers

only weakly involved in the directregulationof in union elections, etc.

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FACTORYREGIMES UNDER ADVANCED CAPITALISM 597

the form of state interventions. Examined kers, as evidenced in the prevalenceof systems

staticallythere is no way of giving primacyto of subcontracting (Littler, 1982: chapter 6).

one directionof determinationover the other. Competition among firms weakened capital

Considered dynamically, however, as I will and increased its dependence on labor. Thus,

suggest below, the direction of determination relative to other countries, English workers

springs from the substratum of relations of were often better organized to resist capital.

production.The combined and uneven devel- We can see this in the early development of

opment of capitalism-that is, the timing and craft unions, although as Turner has persua-

character of the juxtaposition of advanced sively argued(1962: part IV), the sectionalism

forms of capitalism and pre-capitalist of craft unions would eventually retardthe de-

societies-shapes the balanceof class forces in velopment of a cohesive labor movement,

production,setting limits on subsequentforms postponingthe developmentof general unions

of the factory regimeand its relationshipto the until late in the nineteenth century.

state. In the manufacturingsector, in particular

engineering industries, the strength of craft

unions retarded mechanization and provided

England

the basis of continuing shop-floor control, as

We can begin with Englandand its distinctive we saw at Jay's (Clegg, 1979:chapter2). Only

pattern of proletarianization. In the early in the last decade has there been a shift from

stages of industrialization,workerswere either informal,fragmentedworkplace bargainingto

expelled from the ruralareas or they migrated plant-wide agreements (Brown, 1981). Par-

to town of their own accord. By the end of the ticularlyin the new industrieswith automated

nineteenth century all new reserves of labor production, factory regimes more closely ap-

had been exhausted. Although being cut off proximatethe United States pattern(although

fromaccess to means of subsistence weakened comparisons with France suggest that this

workersas individuals,it also impelledthem to change shouldnot be exaggerated[Nichols and

develop collective organization. In countries Beynon, 1977; Gallie, 1978]).

which industrializedlater, wage laborersoften In England the transition from despotic to

had access to alternativemodes of existence, hegemonic regimes has been gradual. Craft

in particularsubsistence productionand petty traditionsled the labor movement to advance

commodity production, undermining its position throughthe control of production

working-classorganization. and labor market rather than through state-

Britain's second phase of industrialization imposed regulations. Trade unions and the

(1840-1895) was dominatedby the search for Labour Party aimed to keep the state out of

outlets for its accumulated capital, which production (Currie, 1979). Employers, con-

turnedto exports based on the developmentof cerned to protect their autonomy to bargain

heavy industryat home. In addition, Britain's directly with labor, were equally mistrustfulof

imperialexpansion laid the basis of class com- state intervention. As the postwar consensus

promise between labor and capital unraveledin the 1960s, Labourand Conserva-

(Hobsbawm, 1969:chapters 6-8). As the ero- tive governments tried to impose incomes

sion of the BritishEmpirewas gradual,so was policies, but with little success. As the Dono-

the changingbalance of class forces. As a re- van Commission of 1968 underlined, work-

sult, British labor history offers no parallelto place bargainingoutside the control of trade

the powerful wave of strikes that swept the union leadership underminedany centralized

United States in the 1930s. Even the General wages policy. Therefore, beginningin the late

Strike of 1926 soon fizzled out and markeda 1960sgovernmentssought to regulateproduc-

definite weakening of labor through the con- tion politics throughlegislativemeasures.Most

tainment of factory politics (Currie, 1979: famous of these was the IndustrialRelations

chapter 4). Act of 1971,which attempteda comprehensive

If the patternsof proletarianizationand col- restructuring of production politics by re-

onialism provided the impetus and the condi- stricting the autonomy of trade unions. For

tions for labor to erect defenses against the three years the trade unions mounteda unified

encroachmentof capital, it was the develop- assault on the act, until the Conservativegov-

ment of capitalistproductionthat providedthe ernment was forced out of office. The new

means. As a pioneer industrialnation, English Labour government repealed the law in 1974

capitaltraversedall the stages of development, and, as part of the "social contract,"a spate of

from handicraftsthroughmanufactureto mod- new laws was introduced. The Trade Union

em industry.From the earliestbeginningscap- and LabourRelationsAct of 1974(amendedin

ital and laboradvancedtogether, strengthening 1976),the EmploymentProtectionAct of 1975,

each other through struggle. Capital was de- the Healthand Safety at WorkAct of 1974,and

pendenton the skills of preindustrialcraftwor- the Sex DiscriminationAct and Race Relations

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

598 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICALREVIEW

Act of 1976 all protected the rights of em- enthusiasm. Denounced by industry, ignored

ployees and trade unions, but within narrower by the Roosevelt administrationand the courts

limits. However, these statutory reforms did but supportedby the AF of L, RobertWagner,

not of themselves have much impact on pro- aided by a series of fortuitous circumstances,

duction politics (Clegg, 1979:chapter 10). The maneuveredthe National Labor RelationsAct

real forces behind changes in productionpoli- throughCongressin 1935(Skocpol, 1980).The

tics must be sought in the changingrelationsof National Labor Relations Board set about re-

capital and labor as part of broadereconomic placing despotic productionpolitics with new

changes, as we shall see in the last section. forms of "industrial government" based on

collective bargaining, due process, com-

promise and independentunions.

In the immediate aftermath, unions devel-

The United Stctes

oped through the momentum of self-

Comparedto England,capital moved through organization,but in the face of a renewed em-

its stages of development more rapidly in the ployer offensive in 1937-1939, the NLRB

United States while proletarianizationpro- helped to defend workers' gains. In 1939 the

ceeded more slowly. The development of en- Boarditself came underheavy attackfor being

claves of Bla~kand immigrantlaborcombined too partisan, forcing a moderation of its

with mobile white workers to balkanize and policies. Subsequently, the National War

atomize the labor force, militating against Labor Board (1942-1946) guided the develop-

strong unions. With the notable exception of ment of unions-establishing their security but

the IWW,those unions that did form were usu- curtailingtheir autonomy. Collective bargain-

ally craft unions. During World War One ing was confinedto wages, hours, and a narrow

unions enjoyed a short reprievefrom the open conception of working conditions; grievance

shop drive. Arbitrary employment practices machinery defined the role of unions as re-

such as blacklisting, imposition of "yellow active; and an army of labor experts was

dog" contracts, and discrimination against created to interpret and administer the law

unionmemberswere prohibited,and laborwas (Harris, 1982). Taft-Hartleyonly represented

protected from arbitrary layoff through the the culmination of a decade-long process in

enforcementof the seniority principle(Harris, which the pressure of class forces constrained

1982). Employers renewed their offensive factory politics within ever narrower limits.

against independent unions in the 1920s, and Over time the NLRB was molded to the needs

company unions were created in their stead. of capital: industrialpeace and stability.

This was the era of welfare capitalism when Nevertheless, the emergentlabor legislation

despotic factory regimes were combined with that governed the postwarperiod still bore the

materialconcessions in the form of social ben- marksof the period in which it was created, in

efits. Companypaternalismcollapsed with the particularthe response to despotic factory re-

Depression as unemployment increased and gimes and the dependenceof workerson capri-

wages and benefits were cut (Brody, 1979: cious market forces. On the one hand, social

chapter 2). Massive strike waves assaulted and laborlegislationoffered, albeit in a limited

productionapparatusesas the source of eco- way, the one thingworkersstrove for above all

nomic insecurity. Despite rising unemploy- else: security. Welfarelegislation, particularly

ment, workers were able to exploit the inter- unemploymentcompensation, although slight

connectedness of the labor process and the compared with that in other countries, meant

interdependence of branches to bring mass that labordid not have to put up with arbitrary

production industries to a standstill. At the employment practices. As we saw at Allied,

same time the exhaustion of new supplies of rightsattached to seniority and union recogni-

nonproletarianized labor limited capital's tion did offer certain protections within the

ability to counter the strikes (Arrighi and plant. On the other hand, dismayed with the

Silver, 1983). initial legislation, capital has managed to re-

Only an independentinitiativefromthe state shape it in its own image, containingconflict

in opposition to capital could pacify labor, an within narrowlimits throughrestrictivecollec-

eventualitymadepossible by the fragmentation tive bargaining and grievance machinery.

of the dominant classes in this period. The Internal labor markets may have offered se-

Norris-LaGuardiaAct of 1932,followed by the curity to labor but, by the same token, they

National IndustrialRecovery Act of 1933, in- introduceda predictabilityto the labor market

spired union organizing efforts, even though that corporatecapital had already achieved in

both had uncertainconstitutionalvalidity and supply and product markets. Even the social

ineffective enforcement mechanisms. Never- legislation which boosted the purchasing

theless, the newly created National Labor power of the workingclass, reconstitutingthe

Board pursued its mission with bureaucratic consumption norm around the house and the

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FACTORYREGIMES UNDER ADVANCED CAPITALISM 599

automobile, steered capital out of its crisis of World War Two, Japan adopted labor laws

overproduction(Aglietta, 1979). similarto those of the United States, but these

If, in the course of time, corporate capital have not led to the same extensive state regu-

would stamp its interests on the new labor lation of productionapparatuses.In the early

legislation, small-scale competitive capital years of the United States occupation, trade

could not afford concessions to labor, and unions expandedtheir membershipfrom under

unionizationin this sector faced greaterobsta- a million in 1946 to over 6.5 million in 1949.

cles. A distinctive dualismdeveloped in which However, the consequences of the top-down

the gains of the corporate sector came at the formation of unions through legislative acts

expense of the competitive sector. In England, were very different from the plant-by-plant

where unionizationhad developed before the conquests that shaped production politics in

consolidationof large corporationsand across the basic industries of the United States.

most sectors of industry, dualism has been Where militantenterprise unions did develop,

weaker. In summary, the very success of they were often replaced by management-

United States capital in maintainingits domi- sponsored "second unions" (Halliday, 1975:

nation over labor through factory despotism chapter 6; Kishimoto, 1968; Levine,

simultaneouslycreated crises of overproduc- 1965:651-60; Cole, 1971: chapter 7). Labor

tion and unleashed massive resistance from legislation has not held back the development

labor, demandingstate interventionand the in- of an authoritarianpolitical order within the

stallationof a new politicalorderin the factory. Japanese enterprise.

The hegemonic regimes which established The basic organizationalunit of the trade

themselves after World War Two, such as the union is the enterprise. Its leadershipis often

one at Allied, underminedlabor's strengthon dominated by managerialpersonnel and pro-

the shop floor, leading to its present vulnera- vides little resistanceto the unilateraldirection

bility. of work. At best, it is a bargainingagency for

wage and benefit increases, and even then it is

usually a matterof average increases, internal

Japan distributionbeing left largelyto management's

discretion(Evans, 1971:132).In the bargaining

It is difficult to penetrate the mythologies of itself unions generally accept the parameters

harmony and integration associated with the defined by managementwithout reference to

Japanese hegemonic regime, but for that rea- rankand file (Dore, 1973:chapters 4, 6; Cole,

son the task is all the morenecessary. It is easy 1971: chapter 7). Moreover, the few conces-

to miss the coercive face of paternalism.3Of sions unionized (permanent)employees may

our four cases, the Japanese most closely ap- obtainwithinlargeenterprisescome, at least in

proximates the despotic order of early part, at the expense of the temporary em-

capitalismin which the state offers little or no ployees (up to 50 percentof the total), of which

social insuranceand abstains from the regula- a large proportionare women. There are few

tion of factory apparatuses.In the aftermathof avenues for workers to process grievances.

They must rely on personal appeals to their

I Because few ethnographic studies of work in immediatesupervisor, who often is also their

Japanese factories have been available in English, union representative (Cole, 1971:230).

the translation of Satoshi Kamata's account (1983) of Moreover, in the absence of regularizedproce-

his experiences as a seasonal worker at Toyota is dures for moving betweenjobs, such as a bid-

particularly welcome. He presents a rich and de- ding system, workers can exercise little au-

tailed description of the factory regime: the company tonomy in relation to their supervisors (Cole,

union is inaccessible and unresponsive to the mem-

bership; outside work, life in the dormitories is sub-

1979:111, 114). The result is intense rivalry

ject to police-type surveillance; on the shop floor among workers (Cole, 1971: chapter 6). Un-

workers face the arbitrary domination of manage- doubtedlyJapanese "paternalism"has its des-

ment, whether this concerns compulsory transfers potic side.

between jobs, speed-up, overtime or the company's The unusually low level of state-provided

carefree attitude toward industrial accidents. Reg- social insurance compounds employees' sub-

ular employees face equally oppressive conditions ordination,makingthem dependenton the en-

but have more to lose (in terms of fringe benefits) by terprisewelfare system for housing, pensions,

quitting than do the seasonal workers. As one of sickness benefits and so on. Dore (1973:323),

Kamata's co-workers put it, life-time employment

becomes a life-time prison sentence. In his introduc-

for example, has calculated that receipts other

tion, Ronald Dore tries to explain away the coercive

than direct payment for labor were divided in

features at Toyota in the early 1970s as atypical, but the ratioof four-to-onein favor of enterpriseas

the fact that they exist at all in such a large corpora- opposed to state benefits in Japan, whereas in

tion says a great deal about hegemonic regimes in Britainthe division was roughly equal. In the

Japan. corporate sector of the Japanese economy,

This content downloaded from 130.60.206.43 on Thu, 18 Jul 2013 10:35:30 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

600 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

where the nenko system of "lifetime employ- Sweden

ment" has been most fully developed, the im-

portance of enterprise benefits is corre- Ourfourthcase, Sweden, is the polar opposite

spondinglygreater. Since benefits and wages of Japan. Here we find state regulationof pro-

are linked to length of service, the longer ductionpolitics combinedwith one of the most

workers remain with a company the more highly developed welfare systems. Underpin-

costly it is to move to anotherfirm, the more ning this pattern is the "Swedish model" of

they identify with the firm's interests, and the class compromise, developed during the 44

greater their stake in company profits. This years of socialdemocraticrule (1932-1976)and

dependence on the enterprise, without the revolving around the centrally negotiated

countervailing feature of the United States "frame agreement" between the employers'

system of internallabormarketsand grievance federation (SAF), the federation of industrial

machinery,leaves labor with fewer opportuni- unions (LO) and the largest white-collarfeder-

ties to carve out arenas of resistance. ation (TCO). Sweden is unique among the ad-

One can begin to explain the Japanese sys- vanced capitalist countries in that 87% of its

tem of productionpolitics in terms of the tim- paid labor force is unionized. LO represents

ing of industrializationand the availabilityof 95%of blue-collarworkers, while TCO repre-

reserves of cheap labor. Late development sents 75%of salaried employees. SAF covers

meant that the early stages of industry- the entire private sector. Both LO and SAF

handicrafts and manufacture-were skipped, exercise power, includingsignificanteconomic

with direct entry into modern industry with sanctions, over their member organizations

large-scale enterprises. The recruitmentfrom (Korpi, 1978: chapter 8; Fulcher, 1973:50).

the ruralreserves of laborcompoundedlabor's The central frame agreement provides the

defenselessness againstcapital.Japaneselabor basis for both industry bargainingand collec-

never developedjob rights andjob conscious- tive bargainingat the plant level. Two princi-

ness, so central in the United States, because ples informthe central bargaining.The first is

industry never passed through an intensive an incomes policy which attempts to keep

phase of scientific managementand detailed wage increases withinlimits so as to guarantee

division of labor which rests on careful job the internationalcompetitiveness of Swedish

specification. The very concept of job is industry. The second is a "solidaristic wages

amorphous and job boundaries are more policy" which attempts to equalize wage dif-

permeablethan in the early industrializingna- ferentials across sectors. Apart from the goal

tions. Insteadof a system of rightsand obliga- of social equity, the principleof equal pay for

tions there developed a moreflexible system of equal work irrespective of the employer's

work-grouprelations and job rotation which abilityto pay is designed to encouragetechno-

permits a limited collective initiative that is logical change and to force uncompetitiveen-

carefully monitored from above (Cole, 1979: terprisesout of business. At the same time, the

chapter7). As in the United States, the corpo- Swedish welfare system offers compensation

rate sector with its welfare regimes has ad- for those laid off, and an active manpower

vanced at the expense of the subordinatecom- policy redistributes workers in accordance

petitive sector. Dualism is, if anything, more with the needs of capital. In short, whilecapital

markedin Japanthan in the United States by accepts the centralized wages policy, trade

virtueof the weakness of both laborand capital unionsare expected to cooperate in the pursuit

in sectors dependent on large corporations. of efficiency.

Just as welfare capitalism in the United Swedish central wage agreements are not

States broke down with the Depression, so the determinateat the level of the firm, although

Japanese "permanentemployment system" is they are more closely adhered to than in En-