Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Nej MSR 1707974

Enviado por

anggiTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Nej MSR 1707974

Enviado por

anggiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

Spe ci a l R e p or t

Investing in Global Health for Our Future

Victor Dzau, M.D., Valentin Fuster, M.D., Ph.D., Jendayi Frazer, Ph.D., and Megan Snair, M.P.H.

With connectedness among countries increasing, In this context, the National Academies of Sci-

the United States exists in a highly interdepen- ences, Engineering, and Medicine was charged

dent world. All countries are now vulnerable to with conducting a consensus study to provide

the ever-present threats of infectious disease out- recommendations to the U.S. government and

breaks and epidemics, as well as the continuous other stakeholders to increase responsiveness,

challenges of malaria, tuberculosis, and human coordination, and efficiency by establishing global

immunodeficiency virusacquired immunode- health priorities and mobilizing resources. With

ficiency syndrome (HIVAIDS). Furthermore, the support from a broad array of federal agencies,

increasing prevalence of chronic noncommuni- foundations, and private partners, an ad hoc

cable diseases (NCDs) has negatively affected 14-member committee was appointed to carry

global health and economies, compromising out this task over the course of 8 months. On

societal gains in life expectancy, productivity, the basis of a rigorous and evidence-based con-

and overall quality of life.1 In addition to resulting sensus process, the committee formulated a set

in the loss of lives, these disease burdens can of 14 recommendations; we believe that the im-

stall the progress of a countrys development plementation of these recommendations would

and significantly affect its ability to become a result in a strong global health strategy and allow

strong trading partner or a business or travel the United States to maintain its role as a global

destination. Human capital clearly contributes health leader.2

substantially to economic growth, and it follows

that having a healthy population is critical for Over vie w of Commit tee Rep or t

economic prosperity. For all these reasons, the Prioritie s

health of other countries has a great influence

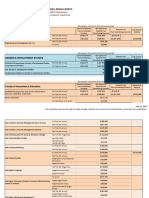

on the health, security, economy, and well-being The report recommends setting four main priori-

of the United States. At the same time, interdepen- ties: pursuing global health security, addressing

dency brings opportunities for shared innovation continuous communicable threats, saving and

and universal purpose in response to similar improving the lives of women and children, and

disease burdens across countries. promoting cardiovascular health and preventing

The United States has long been a world cancer (Fig.1).

leader in global health, and its investment has

led to considerable success through programs Ensuring Global Health Security

such as the Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS The U.S. Army recently estimated that if a severe

Relief (PEPFAR); the Presidents Malaria Initia- infectious disease pandemic were to occur today,

tive (PMI); the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuber- the number of U.S. fatalities might well be nearly

culosis, and Malaria; and more recently, the double the total number of battlefield fatalities

Global Health Security Agenda. As a result of sustained in all U.S. wars since the American

such successes, there has been strong bipartisan Revolution.3 Regardless of whether epidemics or

support and relatively stable funding for global biosecurity threats originate naturally or through

health for the past 15 years. However, with the human engineering, it is critical for the United

change in presidential administration, and with States to recognize their severity and take pro-

many new and recurring crises crowding the active measures to build capacities and establish

policy agenda, the future direction of U.S. global sustainable and cost-effective infrastructure to

health is unclear. combat them.

1292 n engl j med 377;13nejm.org September 28, 2017

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 30, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Special Report

Although multiple agencies can bring unique

expertise to a U.S.-governmentled response to

Securing against Enhancing Productivity

an international health emergency, it is difficult Global Threats and Economic Growth

to execute an emergency plan in the midst of

a crisis without a clear chain of command, a Global Continuous Saving and Promoting

dedicated budget, and designated leadership. Health Security Communicable Improving the Cardiovascular

Threats Lives of Women Health and

The committee called for a coordinating body to and Children Preventing Cancer

oversee this type of response, guided by a newly

created international response framework. To

Maximizing Returns

rapidly mobilize assets and implement interven-

tions when necessary, the committee also sup- Catalyzing

Smart Financing

Global Health

Innovation Leadership

ports the creation of a public health emergency

response fund, to be used only in declared health

emergencies. This fund should be complement-

ed by parallel dedicated funding streams for the

development of needed vaccines, diagnostics, and Figure 1. Issues Addressed by the National Academies of Sciences,

therapeutics for global health threats, as well as Engineering, and Medicine Report on Global Health and the Future

of the United States.

supporting preparedness actions such as build-

ing public health infrastructure. A dual focus on

health preparedness through capacity building

at home and abroad is essential to reduce the than treating it. Cost-effective investments made

risk of outbreaks and the transmission of infec- during a childs early years can mitigate deleteri-

tious disease globally. ous effects of poverty and social inequality. In

fact, interventions carried out during the very

Addressing Continuous Communicable early years of life can translate into lifelong bene-

Threats fits in terms of labor-market participation, earn-

Although potential emerging or recurring pan- ings, and economic growth generating finan-

demics often captivate the media and dominate cial returns of up to 25%.7 Given the robust

the dialogue regarding global health threats, the evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of inter-

global community must not forget the persistent ventions for preventing maternal and child deaths,

health priorities the world has been addressing the committee agreed that accelerating invest-

for several decades: HIVAIDS, tuberculosis, and ments in this area will be vital. To avoid further

malaria. Each year, 2 million people around the preventable deaths, the committee recommended

world acquire HIV infection,4 and more people increased funding so that the U.S. Agency for

now die from tuberculosis than from AIDS.5,6 International Development (USAID) can augment

Complacency toward these diseases can lead to its investments. Ensuring that women and chil-

severe risk for the global community, since all dren thrive, however, is also critical: 250 million

three pathogens are capable of evolving into children under 5 years of age in low- and middle-

strains that are resistant to currently available income countries (LMICs) are failing to reach

treatments. The committee called for sustained their development potential owing to extreme

commitment to the PEPFAR and PMI programs, poverty and stunting.8 Building empowering, nur-

but also for broadening PEPFAR to make it more turing, and cognitively enriching environments

flexible and to incorporate chronic health condi- to prevent such stunting and promote healthy

tions. Finally, the committee recommended a and productive lives requires programs that span

thorough assessment of the tuberculosis threat the health, education, and social service sectors.

so that the world can plan for the true danger it

presents. Promoting Cardiovascular Health

and Preventing Cancer

Investing in Womens and Childrens Health Premature death and disability stemming from

Ideally, prevention efforts should begin at birth NCDs contribute to decreased productivity, de-

and continue throughout the course of each per- creased gross domestic product, and higher over-

sons life, since preventing disease is less costly all costs of health care because established health

n engl j med 377;13 nejm.org September 28, 2017 1293

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 30, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e

systems are not designed to care for people with multilateral partnerships such as the Global Fund

chronic disease in an integrated and holistic and Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance. LMICs may also

fashion.9 As more people survive infectious dis- benefit from allocation of increased funds to

eases and age into adulthood, many develop multilateral institutions, which can provide global

cardiovascular disease or cancer, conditions to public services that many countries cannot man-

which global health programs are not devoting age independently, such as research and develop-

adequate attention. The committee recommends ment, knowledge sharing, shaping of the health

that national and donor governments and non- care market,12 and management of cross-border

governmental organizations address these priori- challenges.13

ties through policy changes and community- Overall, the committee recommends contin-

based programs that are integrated into existing ued U.S. government investment in global health

health services. The committee calls for USAID, to maintain the success of recent decades, but

the Department of State, and the Centers for also calls for a reevaluation of the way global

Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to provide health business is conducted, in order to improve

seed funding at the country level to facilitate outcomes and cost-effectiveness. In doing so,

mobilization and involvement of the private sector the committee recognizes that business as

in addressing these issues. High-priority strate- usual will not be sufficient. The majority of

gies include the targeting and management of foreign aid, especially when directed toward

risk factors, detection and treatment of early health, is an investment and should be treated as

hypertension and early cervical cancer, and im- such. The benefits for the United States are two-

munization for vaccine-preventable infections, fold: securing protection against global health

such as human papillomavirus and hepatitis B threats and promoting productivity and eco-

virus, that can lead to cancer. nomic growth in other countries. These benefits

can be increased through strategies that maxi-

mize returns on investment (Fig.2). To have the

Changing the Appr oach

and Ma ximizing Re t urns greatest effect in the four described priority

areas, the committee identified three cross-cutting

The committee envisions its recommendations as strategies that can both maximize returns and

part of a more proactive, systematic, and cross- achieve better health outcomes: catalyzing inno-

cutting approach to global health; the core con- vation through accelerated development of med-

cepts underlying its analysis are integration, capac- ical products and building of integrated digital

ity building, and partnership. Though integration health infrastructure; employing more nimble

can be difficult, and often must be considered and flexible financing mechanisms to leverage

even before a program is developed, changes in new partners and funders in global health; and

health system design can permit more holistic maintaining the status and influence of the

care and result in greater effectiveness in improv- United States as a world leader in global health

ing health outcomes. Given that patients often while adhering to evidence-based science, eco-

have both communicable and noncommunicable nomics, measurement, and accountability.

diseases, integrating services by sharing loca-

tions, staff, systems, tools, and strategies can Catalyzing Innovation

increase effectiveness.10 For example, researchers In terms of medical product development, the

in Zambia noted that using the existing HIVAIDS market for global health products suffers from

care infrastructure for cervical cancer screening numerous failures including inadequate manu-

has positive effects on costs, reliance on avail- facturing capacity, a costly approval process, un-

able expertise, and sustainability.11 certain commercial potential, and poor workforce

Similarly, building capacity throughout a coun- and laboratory capacities in LMICs. Because of

trys health system can foster greater resilience the dearth of available medical products, many

and an ability to respond to a range of chal- patients with tuberculosis, malaria, or other

lenges, whether an infectious disease outbreak potential pandemic diseases lack access to es-

or an aging population with complex needs. sential medicines. Developing safe and effica-

Successfully integrating a countrys programs cious products requires not only a secure mar-

and building its capacity will require strong ket, but also local research and development

1294 n engl j med 377;13nejm.org September 28, 2017

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 30, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Special Report

capacity in countries where outbreaks begin and

Report Themes Recommendations

disease burdens are high.14 The U.S. government

can enable innovative approaches for trial de- Securing Improve coordination during international public health

emergency preparedness and response efforts.

sign, streamline regulation, and ensure produc- against

Global Reduce antimicrobial resistance through enhanced

tion capacity and market incentives in order to Threats surveillance, quality-controlled supply chains, and improved

accelerate the development of medical products. stewardship.

Equally critical in this process, and an ongoing Build public health capacity in other countries for better

response to infectious disease outbreaks and disasters.

priority, is creating sustainable international

Broaden PEPFAR to provide chronic care emphasizing

capacity for research and development, as the country ownership and partnership with the Global Fund.

Fogarty International Center of the National In- Conduct a global threat assessment of tuberculosis; maintain

stitutes of Health has been working to do. commitment to the Presidents Malaria Initiative.

In terms of technology, the proliferation of

digital health applications and platforms in coun-

Enhancing Accelerate investments in survival of women and children;

tries around the world has resulted in increasing Productivity improve developmental potential and well-being.

fragmentation across sectors and organizations, and Promote cardiovascular health and prevent cancer by

even as it has created opportunities for health Economic targeting risk factors and implementing best practices.

system innovation. Cross-cutting digital health Growth

platforms should be interoperable and yet adapt-

able to local requirements and sovereignty. New Maximizing Catalyze innovation to accelerate medical product

development and streamline digital health tools.

and existing U.S. investments can employ a vision Returns

of building once, and U.S. and international Use financing that envisions long-term goals and optimizes

resources using innovative methods and diverse sources of

stakeholders can come together to create a com- capital.

mon framework that could be used and adapted Commit to U.S. global health leadership through multilateral

worldwide in a manner that is scalable for future- partnerships and creation of a U.S. global health workforce.

minded solutions.

Optimizing Financing Figure 2. Recommendations of the National Academies of Sciences,

As many LMICs graduate from receiving devel- Engineering, and Medicine Ad Hoc Committee on Global Health

and the Future of the United States.

opment assistance, their governments can crowd

in other funding sources, such as the private

sector, by both increasing demand for goods

through public funds and sharing risk to cata- issues and active engagement in the interna-

lyze private investments that would not otherwise tional global health arena. The United States has

be made.15 Such efforts could include seeding an opportunity to solidify its leadership and take

investment funds, offering incentives to local a more deliberate approach to foreign policy. In

financial institutions through credit guarantees, addition to a continued commitment to interna-

or providing technical assistance to strengthen tional partnerships, the committee calls for the

business management in companies. In particu- establishment of a sustainable U.S. workforce in

lar, the committee recommends that the U.S. global health. In the absence of a health career

government should diversify its methods of track in the Foreign Service, the demand for U.S.

global health funding to be more targeted and global health expertise in host countries cannot

catalytic, thereby increasing the impact and cost- be sustainably filled, and the U.S. personnel who

effectiveness of its investments. Moreover, the are deployed often lack appropriate health or

U.S. government can conduct more strategic and diplomacy skills, which weakens U.S. global

systematic assessments and use them to make awareness and readiness.

long-term investments in global health that con-

tribute to global public good rather than short- Conclusions

term expenditures.

The United States cannot ignore the reality that

Committing to U.S. Global Health Leadership the health and well-being of other countries af-

Finally, protecting U.S. citizens at home and fect the health, safety, and economic security of

abroad necessitates continued awareness of global Americans. For many years, there has been strong

n engl j med 377;13 nejm.org September 28, 2017 1295

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 30, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Special Report

bipartisan backing of U.S. engagement in global 2. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Global health and the future role of the United States. May 15, 2017

health, with active support from the faith com- (http://nationalacademies.org/hmd/reports/2017/g lobal-health

munity, private industry, foundations, and civil -and-the-future-role-of-the-united-states.aspx).

society. The committee believes that implement- 3. Defense civil support:DoD, HHS, and DHS should use exist-

ing coordination mechanisms to improve their pandemic pre-

ing evidence-based interventions, modifying coun- paredness. Washington, DC:Government Accountability Office,

try engagement strategies, exploring new invest- 2017.

ment mechanisms, and taking a more proactive 4. PEPFAR (U.S. Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief).

PEPFAR 2016 annual report to congress. Washington, DC:Office

and systematic approach to global health priori- of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and Health Diplomacy, 2017.

ties will make the U.S. governments efforts in 5. UNAIDS. Fact sheet:latest statistics on the status of the

global health more effective and efficient. The AIDS epidemic. November 2016 (http://www .unaids

.org/

en/

resources/fact-sheet).

United States can preserve and extend its legacy 6. Global tuberculosis report 2016. Geneva:World Health Orga-

as a global leader, partner, and innovator in nization, 2016.

global health through forward-looking policies, 7. Gertler P, Heckman J, Pinto R, et al. Labor market returns to

an early childhood stimulation intervention in Jamaica. Science

a long-term vision, country and international 2014;344:998-1001.

partnerships, and most important, continued in- 8. Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LCH, et al. Early childhood

vestment. Doing so will not only lead to improved development coming of age: science through the life course.

Lancet 2017;389:77-90.

health and security for all U.S. citizens but also

9. Health reform:meeting the challenge of ageing and multiple

ensure the sustainable thriving of the global morbidities. Washington, DC:Organization of Economic Co-

population. operation and Development, 2011.

10. Rabkin M, Kruk ME, El-Sadr WM. HIV, aging and continuity

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with

care: strengthening health systems to support services for non-

the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

communicable diseases in low-income countries. AIDS 2012;26:

The members of the Committee on Global Health and the

Suppl 1:S77-S83.

Future of the United States are Jendayi Frazer (cochair), Council

11. Parham GP, Mwanahamuntu MH, Kapambwe S, et al. Popu-

on Foreign Relations; Valentin Fuster (cochair), Mount Sinai

lation-level scale-up of cervical cancer prevention services in a

Medical Center, New York; Gisela Abbam, General Electric

low-resource setting: development, implementation, and evalua-

Healthcare; Amie Batson, PATH; Frederick Burkle, Jr., Harvard

tion of the cervical cancer prevention program in Zambia. PLoS

University; Lynda Chin, University of Texas System; Lia Haskin

One 2015;10(4):e0122169.

Fernald, University of California, Berkeley; Stephanie Ferguson,

12. USAID Center for Accelerating Innovation and Impact.

Lynchburg College and Stanford University; Peter Lamptey, FHI

Healthy markets for global health:a market shaping primer. Fall

360; Ramanan Laxminarayan, Centers for Disease Dynamics,

2014 (https://w ww.usaid.gov/sites/default/f iles/documents/1864/

Economics, and Policy; Michael Merson, Duke University; Vasant

healthymarkets_primer_0.pdf).

Narasimhan, Novartis; Michael Osterholm, Center for Infectious

13. Schferhoff M, Fewer S, Kraus J, et al. How much donor fi-

Disease Research and Policy; and Juan Carlos Puyana, University

nancing for health is channelled to global versus country-specific

of Pittsburgh.

aid functions? Lancet 2015;386:2436-41.

14. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

From the Office of the President, National Academy of Medi-

Integrating clinical research into epidemic response:the Ebola

cine (V.D.), the Committee on Global Health and the Future of

experience. Washington, DC:National Academies Press, 2017.

the United States (V.F., J.F.), and the Health and Medicine Divi-

15. Powers C, Butterfield WM. Crowding in private investment.

sion (M.S.), National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and

In:Shah R, Unger N, eds. Frontiers in development: ending ex-

Medicine, Washington, DC; Centro Nacional de Investigaciones

treme poverty. Washington, DC:U.S. Agency for International

Cardiovasculares, Madrid (V.F.); and Mount Sinai Hospital (V.F.)

Development, 2014.

and the Council on Foreign Relations (J.F.) both in New York.

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsr1707974

1. The global risks report 2017. Geneva:World Economic Fo- Copyright 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society.

rum, 2017.

1296 n engl j med 377;13nejm.org September 28, 2017

The New England Journal of Medicine

Downloaded from nejm.org on September 30, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Você também pode gostar

- Staples Worklife Magazine - Winter 2019Documento68 páginasStaples Worklife Magazine - Winter 2019Anonymous fq268KsS100% (1)

- MediterraneanDocumento39 páginasMediterraneanJeff Lester PiodosAinda não há avaliações

- ASHRAE Std 62.1 Ventilation StandardDocumento38 páginasASHRAE Std 62.1 Ventilation Standardcoolth2Ainda não há avaliações

- Dr. LakshmayyaDocumento5 páginasDr. LakshmayyanikhilbAinda não há avaliações

- Global Health Issues PPDocumento91 páginasGlobal Health Issues PPRitaAinda não há avaliações

- Global Health Is Public HealthDocumento3 páginasGlobal Health Is Public HealthDr Vijay Kumar Chattu MD, MPHAinda não há avaliações

- Dementia Rating ScaleDocumento2 páginasDementia Rating ScaleIqbal BaryarAinda não há avaliações

- Project Name: Proposed Icomc & BMC Building Complex Phe Design ReportDocumento19 páginasProject Name: Proposed Icomc & BMC Building Complex Phe Design ReportAmit Kumar MishraAinda não há avaliações

- VaccinesDocumento4 páginasVaccinesInterActionAinda não há avaliações

- Governance For Health - The HIV Response and General Global HealthDocumento2 páginasGovernance For Health - The HIV Response and General Global HealthRainer A.Ainda não há avaliações

- Form 1bDocumento7 páginasForm 1bYudi FeriandiAinda não há avaliações

- Role(s) of Vaccines and Immunization Programs in Global Disease ControlDocumento18 páginasRole(s) of Vaccines and Immunization Programs in Global Disease ControlMarelign Demeke AssayeAinda não há avaliações

- Activity 3Documento3 páginasActivity 3Tristan Jerald BechaydaAinda não há avaliações

- Terapi KankerDocumento7 páginasTerapi KankerRasyidAinda não há avaliações

- OverviewDocumento4 páginasOverviewInterActionAinda não há avaliações

- Emergency Preparedness and Public Health Systems: Lessons For Developing CountriesDocumento6 páginasEmergency Preparedness and Public Health Systems: Lessons For Developing CountriesPatricia TungpalanAinda não há avaliações

- Editorial: Health and The World Conference On Sustainable DevelopmentDocumento1 páginaEditorial: Health and The World Conference On Sustainable DevelopmentdaniAinda não há avaliações

- At The End of The Lesson, The Students Will:: Overview of Public Health Nursing in The Philippines Learning OutcomesDocumento18 páginasAt The End of The Lesson, The Students Will:: Overview of Public Health Nursing in The Philippines Learning OutcomesPABLO, JACKSON P.100% (1)

- H. RES. LL: ResolutionDocumento4 páginasH. RES. LL: ResolutionPeter SullivanAinda não há avaliações

- Acp Statement On Global Covid-19 Vaccine Distribution and Allocation On Being Ethical and Practical 2021Documento3 páginasAcp Statement On Global Covid-19 Vaccine Distribution and Allocation On Being Ethical and Practical 2021Suleymen Abdureman OmerAinda não há avaliações

- CHN 1 FullDocumento88 páginasCHN 1 FullKristine Joy CamusAinda não há avaliações

- World Health OrganizationDocumento4 páginasWorld Health OrganizationLoreth Aurea OjastroAinda não há avaliações

- 1.1 Primary Health Care and NutritionDocumento5 páginas1.1 Primary Health Care and NutritionEmilyBaqueAinda não há avaliações

- Global Health Initiatives: G14 Keisha Rianne T. Perez X-ST - AugustineDocumento2 páginasGlobal Health Initiatives: G14 Keisha Rianne T. Perez X-ST - Augustineyixz 5dmAinda não há avaliações

- Policy Considerations While Transitioning To RecoveryDocumento7 páginasPolicy Considerations While Transitioning To Recoverymutalechanda0509Ainda não há avaliações

- Global Health GoalsDocumento6 páginasGlobal Health Goalsujangketul62Ainda não há avaliações

- Proposal For Long Term COVID 19 Control - v1.0Documento16 páginasProposal For Long Term COVID 19 Control - v1.0bathmayentoopagenAinda não há avaliações

- Global Preparedness Monitoring Board: Executive SummaryDocumento10 páginasGlobal Preparedness Monitoring Board: Executive SummarysofiabloemAinda não há avaliações

- The One Health Approach-Why Is It So Important?: Tropical Medicine and Infectious DiseaseDocumento4 páginasThe One Health Approach-Why Is It So Important?: Tropical Medicine and Infectious DiseaseListyana Aulia FatwaAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 3 Lecture in HEALTH PDFDocumento2 páginasUnit 3 Lecture in HEALTH PDFFebee keith DimapilisAinda não há avaliações

- Blueprint For Global Heatlh ResilienceDocumento27 páginasBlueprint For Global Heatlh ResiliencejuanAinda não há avaliações

- GlobalHealthBriefingBook FINAL Web PDFDocumento66 páginasGlobalHealthBriefingBook FINAL Web PDFAyoade opeyemiAinda não há avaliações

- Global Health and Nursing Group 2Documento16 páginasGlobal Health and Nursing Group 2Kathleen Camile CenaAinda não há avaliações

- Vaccine Conclusion Pbi1102Documento1 páginaVaccine Conclusion Pbi1102IzzulAinda não há avaliações

- Who Ier PSP 2010.3 EngDocumento16 páginasWho Ier PSP 2010.3 EngAdebisiAinda não há avaliações

- Comment: For Lancet On Universal Universal-Health-CoverageDocumento2 páginasComment: For Lancet On Universal Universal-Health-Coverageapi-112905159Ainda não há avaliações

- Infections ControlDocumento6 páginasInfections ControlChris NdirituAinda não há avaliações

- Enfermedades OlvidadasDocumento6 páginasEnfermedades OlvidadasMiriam SolacheAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Vaccines Health, Economic and Social PerspectivesDocumento15 páginasImpact of Vaccines Health, Economic and Social PerspectivesJV BernAinda não há avaliações

- Pitt Et 2008Documento8 páginasPitt Et 2008GrevaldoAinda não há avaliações

- 2015 - Schmidt Et Al Health Coverage and The SDGsDocumento4 páginas2015 - Schmidt Et Al Health Coverage and The SDGsGhostatt CaAinda não há avaliações

- Global Health Role of CDCDocumento4 páginasGlobal Health Role of CDCmysteryperson9569210Ainda não há avaliações

- Towards A Common Defi Nition of Global HealthDocumento4 páginasTowards A Common Defi Nition of Global HealthmjrazaziAinda não há avaliações

- Health Impact Framework 1Documento11 páginasHealth Impact Framework 1api-458055311Ainda não há avaliações

- Hsci 6330 Final ExamDocumento7 páginasHsci 6330 Final Examapi-579553971Ainda não há avaliações

- The Value of Vaccination A Global PerspeDocumento13 páginasThe Value of Vaccination A Global Perspethedevilsoul981Ainda não há avaliações

- Strengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable developmentDocumento3 páginasStrengthening health systems for universal health coverage and sustainable developmentghoudzAinda não há avaliações

- Global Health GIT - Sir ReyDocumento6 páginasGlobal Health GIT - Sir ReyKiel Martin IIAinda não há avaliações

- Koplan2009 - Defincion de Salud GlobalDocumento3 páginasKoplan2009 - Defincion de Salud GlobalIsa SuMe01Ainda não há avaliações

- HEALTH Q3 PPT MAPEH10 Lesson 1 Significance of Global Health Initiatives 1Documento20 páginasHEALTH Q3 PPT MAPEH10 Lesson 1 Significance of Global Health Initiatives 1Alexa Jean MercurioAinda não há avaliações

- Study Guide - Who - Mun Simulation 1.0Documento6 páginasStudy Guide - Who - Mun Simulation 1.019O2OO513 Dava PebrianAinda não há avaliações

- Streefland - Patterns of Vaccination Acceptance-1999Documento12 páginasStreefland - Patterns of Vaccination Acceptance-1999BrenAinda não há avaliações

- Triple Burden - Frenk 2011Documento1 páginaTriple Burden - Frenk 2011Jose RamirezAinda não há avaliações

- Age of PandemicDocumento12 páginasAge of PandemicDavide FalcioniAinda não há avaliações

- Programmes and Activites of Public Nutrition and HealthDocumento24 páginasProgrammes and Activites of Public Nutrition and HealthPrasastha UndruAinda não há avaliações

- Health Impact Framework PaperDocumento6 páginasHealth Impact Framework Paperapi-681892221Ainda não há avaliações

- Understanding the Complex Factors Driving Vaccine Hesitancy in 40 CharactersDocumento6 páginasUnderstanding the Complex Factors Driving Vaccine Hesitancy in 40 CharactersAlexandra Mae D. MiguelAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Diabetes Mellitus, December 2010 (Ala Alwan)Documento60 páginasInternational Journal of Diabetes Mellitus, December 2010 (Ala Alwan)agnes holwardAinda não há avaliações

- Salud GlobalDocumento5 páginasSalud GlobalGabriel Andrés Pérez BallenaAinda não há avaliações

- Final Regional Fact Sheet #6 - MENADocumento5 páginasFinal Regional Fact Sheet #6 - MENAAmjedAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Global Health-2035 PDFDocumento58 páginasJurnal Global Health-2035 PDFYuli RamadaniAinda não há avaliações

- Global Health 2035 Read Pages 1 2 Exec SummaryDocumento58 páginasGlobal Health 2035 Read Pages 1 2 Exec SummaryTony NgAinda não há avaliações

- Vaccines - The Week in Review - 1 February 2010Documento10 páginasVaccines - The Week in Review - 1 February 2010davidrcurryAinda não há avaliações

- World Health Organization (WHO)Documento4 páginasWorld Health Organization (WHO)Krista P. AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- World Health Organization (WHO)Documento4 páginasWorld Health Organization (WHO)Krista P. AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocumento10 páginasNew England Journal Medicine: The ofMari NiculaeAinda não há avaliações

- Remdesivir - BeigelDocumento14 páginasRemdesivir - BeigelMaureen KoesnadiAinda não há avaliações

- New England Journal Medicine: The ofDocumento10 páginasNew England Journal Medicine: The ofMari NiculaeAinda não há avaliações

- Nejmoa 2208822Documento12 páginasNejmoa 2208822Gaspar PonceAinda não há avaliações

- Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans Across 16 Countries - April-June 2022Documento14 páginasMonkeypox Virus Infection in Humans Across 16 Countries - April-June 2022Raphael Chalbaud Biscaia HartmannAinda não há avaliações

- Nej MC 2200133Documento3 páginasNej MC 2200133anggiAinda não há avaliações

- Achieving The Triple Aim For Sexual and Gender Minorities: PerspectiveDocumento4 páginasAchieving The Triple Aim For Sexual and Gender Minorities: PerspectiveanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Nej MP 2210125Documento3 páginasNej MP 2210125anggiAinda não há avaliações

- Many Authors in Business Management Research Papers Wrongly Calculate Central Tendency Just Like Wang Et Al. (2019) - This Leads To A Disaster.Documento6 páginasMany Authors in Business Management Research Papers Wrongly Calculate Central Tendency Just Like Wang Et Al. (2019) - This Leads To A Disaster.Scholarly CriticismAinda não há avaliações

- Monkeypox Virus Infection in Humans Across 16 Countries - April-June 2022Documento14 páginasMonkeypox Virus Infection in Humans Across 16 Countries - April-June 2022Raphael Chalbaud Biscaia HartmannAinda não há avaliações

- Nej Me 2207596Documento1 páginaNej Me 2207596anggiAinda não há avaliações

- Audio Interview: Responding To Monkeypox: EditorialDocumento1 páginaAudio Interview: Responding To Monkeypox: EditorialanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Transcriptional Response To Interferon Beta-1a Treatment in Patients With Secondary Progressive Multiple SclerosisDocumento8 páginasTranscriptional Response To Interferon Beta-1a Treatment in Patients With Secondary Progressive Multiple SclerosisanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Superficial Radial Nerve Compression Due To Fibrom 2019 Acta Orthopaedica EtDocumento3 páginasSuperficial Radial Nerve Compression Due To Fibrom 2019 Acta Orthopaedica EtanggiAinda não há avaliações

- In Search of A Better Equation - Performance and Equity in Estimates of Kidney FunctionDocumento4 páginasIn Search of A Better Equation - Performance and Equity in Estimates of Kidney FunctionanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Psychometrical Properties of The Turkish Transla 2019 Acta Orthopaedica Et TDocumento5 páginasPsychometrical Properties of The Turkish Transla 2019 Acta Orthopaedica Et TanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Nej MP 1705348Documento3 páginasNej MP 1705348anggiAinda não há avaliações

- Perspective: New England Journal MedicineDocumento4 páginasPerspective: New England Journal MedicineanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Acta Orthopaedica Et Traumatologica Turcica: H. Utkan Ayd In, Omer Berk OzDocumento3 páginasActa Orthopaedica Et Traumatologica Turcica: H. Utkan Ayd In, Omer Berk OzanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Middle Term Results of Tantalum Acetabular Cups in 2019 Acta Orthopaedica EtDocumento5 páginasMiddle Term Results of Tantalum Acetabular Cups in 2019 Acta Orthopaedica EtanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Mid Term Results With An Anatomic Stemless Shoulde 2019 Acta Orthopaedica EtDocumento5 páginasMid Term Results With An Anatomic Stemless Shoulde 2019 Acta Orthopaedica EtanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Nej Mic M 1701787Documento1 páginaNej Mic M 1701787anggiAinda não há avaliações

- Nej Mic M 1703542Documento1 páginaNej Mic M 1703542anggiAinda não há avaliações

- Mechanical Properties and Morphologic Features of Int 2019 Acta OrthopaedicaDocumento5 páginasMechanical Properties and Morphologic Features of Int 2019 Acta OrthopaedicaanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Acta Orthopaedica Et Traumatologica Turcica: H. Utkan Ayd In, Omer Berk OzDocumento3 páginasActa Orthopaedica Et Traumatologica Turcica: H. Utkan Ayd In, Omer Berk OzanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Gastrointestinal Nursing Volume 7 Issue 1 2009 (Doi 10.12968/gasn.2009.7.1.39369) Cox, Carol Steggall, Martin - A Step By-Step Guide To Performing A Complete Abdominal ExaminationDocumento7 páginasGastrointestinal Nursing Volume 7 Issue 1 2009 (Doi 10.12968/gasn.2009.7.1.39369) Cox, Carol Steggall, Martin - A Step By-Step Guide To Performing A Complete Abdominal ExaminationanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Acta Orthopaedica Et Traumatologica Turcica: Cemil Ozal, Gonca Ari, Mintaze Kerem GunelDocumento4 páginasActa Orthopaedica Et Traumatologica Turcica: Cemil Ozal, Gonca Ari, Mintaze Kerem GunelanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Nej MC 1710384Documento3 páginasNej MC 1710384anggiAinda não há avaliações

- A Woman Considering Contralateral Prophylactic MastectomyDocumento4 páginasA Woman Considering Contralateral Prophylactic MastectomyanggiAinda não há avaliações

- Nematode EggsDocumento5 páginasNematode EggsEmilia Antonia Salinas TapiaAinda não há avaliações

- X. Pronosis and ComplicationDocumento2 páginasX. Pronosis and ComplicationnawayrusAinda não há avaliações

- State Act ListDocumento3 páginasState Act Listalkca_lawyer100% (1)

- Research Paper 4Documento26 páginasResearch Paper 4Amit RajputAinda não há avaliações

- Challenges of Caring for Adult CF PatientsDocumento4 páginasChallenges of Caring for Adult CF PatientsjuniorebindaAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 7 World Population Part B SpeakingDocumento22 páginasUnit 7 World Population Part B SpeakingTâm NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Advances and Limitations of in Vitro Embryo Production in Sheep and Goats, Menchaca Et Al., 2016Documento7 páginasAdvances and Limitations of in Vitro Embryo Production in Sheep and Goats, Menchaca Et Al., 2016González Mendoza DamielAinda não há avaliações

- HAV IgG/IgM Test InstructionsDocumento2 páginasHAV IgG/IgM Test InstructionsRuben DuranAinda não há avaliações

- Anand - 1994 - Fluorouracil CardiotoxicityDocumento5 páginasAnand - 1994 - Fluorouracil Cardiotoxicityaly alyAinda não há avaliações

- Ayurveda Medical Officer 7.10.13Documento3 páginasAyurveda Medical Officer 7.10.13Kirankumar MutnaliAinda não há avaliações

- Theoretical Models of Nursing Practice AssignmentDocumento6 páginasTheoretical Models of Nursing Practice Assignmentmunabibenard2Ainda não há avaliações

- eBR PharmaDocumento5 páginaseBR PharmaDiana OldaniAinda não há avaliações

- EpididymitisDocumento8 páginasEpididymitisShafira WidiaAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Audit ScheduleDocumento2 páginasNursing Audit ScheduleArvinjohn Gacutan0% (1)

- Herbal Toothpaste FactsDocumento26 páginasHerbal Toothpaste Factsmahek_dhootAinda não há avaliações

- Turn Around Time of Lab: Consultant Hospital ManagementDocumento22 páginasTurn Around Time of Lab: Consultant Hospital ManagementAshok KhandelwalAinda não há avaliações

- UWI-Mona 2021-2022 Graduate Fee Schedule (July 2021)Documento15 páginasUWI-Mona 2021-2022 Graduate Fee Schedule (July 2021)Akinlabi HendricksAinda não há avaliações

- Addressing The Impact of Foster Care On Biological Children and Their FamiliesDocumento21 páginasAddressing The Impact of Foster Care On Biological Children and Their Familiesapi-274766448Ainda não há avaliações

- Guide To Referencing and Developing A BibliographyDocumento26 páginasGuide To Referencing and Developing A BibliographyAHSAN JAVEDAinda não há avaliações

- 2017EffectofConsumptionKemuningsLeafMurrayaPaniculataL JackInfusetoReduceBodyMassIndexWaistCircumferenceandPelvisCircumferenceonObesePatientsDocumento5 páginas2017EffectofConsumptionKemuningsLeafMurrayaPaniculataL JackInfusetoReduceBodyMassIndexWaistCircumferenceandPelvisCircumferenceonObesePatientsvidianka rembulanAinda não há avaliações

- Lobal: Food Safety Around The WorldDocumento95 páginasLobal: Food Safety Around The WorldCarol KozlowskiAinda não há avaliações

- Low Back Pain Dr. Hardhi PRanataDocumento57 páginasLow Back Pain Dr. Hardhi PRanataPerwita ArumingtyasAinda não há avaliações

- hw410 Unit 9 Assignment Final ProjectDocumento9 páginashw410 Unit 9 Assignment Final Projectapi-649875164Ainda não há avaliações