Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia, 105 Phil. 875, No. L-11860 May 29, 1959 PDF

Enviado por

Alexiss Mace JuradoTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia, 105 Phil. 875, No. L-11860 May 29, 1959 PDF

Enviado por

Alexiss Mace JuradoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

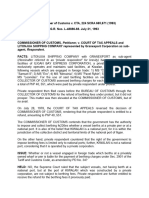

[No. L-11860.

May 29, 1959]

COMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS, petitioner, vs. LT. COL.

LEOPOLDO RELUNIA, respondent.

1. STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION; TITLE OF STATUTE

TO BE RESORTED TO IF THERE is DOUBT AS TO

LEGISLATIVE INTENT.Resort to the title of a statute

as an aid in interpretation thereof is an unsafe criterion,

and is not entitled to much weight. (50 Am. Jur. 301). The

title can be resorted to as aid where there is doubt as to

the meaning of the law or the intention of the legislature

in enacting it. Not otherwise.

2. CUSTOMS; VESSELS INCLUDING PHILIPPINE NAVY

SHIP REQUIRED TO PREPARE AND PRESENT

MANIFESTS.All vessels, whether private or

government-owned, including ships of the Philippine navy,

coming from a foreign port, with the possible exception of

war vessels or vessels employed by any foreign

government, not engaged in the transportation of

merchandise in the way of trade, as provided for in the

second paragraph of Section 1221 of the Revised

Administrative Code, are required to prepare and present

a manifest to the customs authorities upon arrival at any

Philippine Port.

PETITION for review by certiorari of a decision of the

Court of Tax Appeals.

The facts are stated in the opinion of the Court.

Assistant Solicitor General Jose P. Alejandro and

Solicitor Frine C. Zaballero for petitioner.

Ricardo C. Arcilla for respondent.

MONTEMAYOR, J.:

This is an appeal by the Commissioner of Customs from the

decision of the Court of Tax Appeals, the dispositive portion

of which reads:

"FOR THE FOREGOING CONSIDERATION, we are of the

opinion that the forfeiture of the electric range in question under

Section 1363 (g.) is illegal. Accordingly, it is hereby ordered that

the said article be released to the herein petitioner upon payment

of the corresponding customs duties, taxes or charges. Without

pronouncement as to costs."

876

876 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

On December 10, 1953, the RPS "MISAMIS ORIENTAL", a

unit of the Philippine Navy was dispatched to Japan to

transport contingents of the 14th BCT bound for Pusan,

Korea, and carry Christmas gifts for our soldiers there. It

seems that thereafter, it was used for transportation

purposes in connection with the needs of our soldiers there

and made trips between Korea and Japan, so that it did not

return to the Philippines until September 2, 1954. While in

Japan, it loaded 180 cases containing various ,articles

subject to customs duties. These articles have been

classified into three groups, to wit: "(1) those supposed to

be for the Philippine Army Post Exchange, with an

appraised value of $24,197.53, (2) those pertaining to the

Philippine Navy Officers Base Commissary, Cavite, with

an appraised value of $1,590.04, and (3) those belonging to

individuals, consisting of nine Philippine Army and Navy

officers and crew and two private persons, with an

appraised value of $1,772.00."

The rest of the facts which are not in dispute, as well as

the issues involved, particularly the legal ones, are well

stated in the decision of the Court of Tax Appeals now

before us on appeal. We are reproducing pertinent portions

of said decision:

"* * *. All these articles were declared forfeited by the Collector of

Customs of: Manila for violations of the Customs Law in a

decision rendered on March 18, 1955.

"One of the cases containing an electric range 'GE' with four

burners, brought by the RPS 'MISAMIS ORIENTAL' is consigned

to petitioner herein. The said article was forfeited pursuant to

Section 1363 (g) of the Administrative Code as an unmanifested

cargo. On appeal to the Commissioner of Customs, the dispositive

portion of the decision of the Collector of Customs of Manila was

affirmed in toto; hence this appeal.

"Section 1363 (g) of the Administrative Code, upon which the

decree of forfeiture is based, reads as follows:

'SEC. 1363. Property subject to forfeiture under customs laws.

Vessels, cargo, merchandise, and other objects and things shall,

under the conditions hereinbelow specified, be subject to

forfeiture:

*******

877

VOL. 105, MAY 29, 1959 877

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

'(g) Unmanifested merchandise found on any vessel, a manifest

therefor being required.'

"The only question to be decided is whether or not a manifest is

required of the RPS 'MISAMIS ORIENTAL' and, if so, whether or

not the aforesaid electric range is an unmanifested merchandise

within the meaning of Section 1363 (g) of the Administrative

Code.

"The law provides that an 'unmanifested merchandise found on

any vessel, a manifest therefor being required' is subject to

forfeiture. This means that where a vessel is required by law, or

by regulations promulgated pursuant to law, to make and submit

a manifest of its cargo to the customs authorities and it fails to do

so, merchandise not manifested shall be forfeited. Is the RPS

'MISAMIS OSIENTAL' required under the Customs Law to make

and submit to the customs authorities a manifest of its cargo? The

Collector of Customs of Manila says it is, and he has been

sustained by respondent Commissioner of Customs.

"It is argued that Sections 1221, 1225 and 1228 of the

Administrative Code require masters of Government vessels to

submit cargo manifests. Section 1221 provides:

'SEC. 1221. Ports open to vessels engaged in foreign trade

Duty of vessel to make entry.Vessels engaged in the foreign

carrying trade shall touch at ports of entry only, except as

otherwise specially allowed; and every such vessel arriving within

a customs collection district of the Philippines from a foreign port

shall make entry at the port of entry for such district and shall be

subject to the authority of the collector of customs of the port

while within his jurisdiction.

'The master of any war vessel or vessel employed by any

foreign government shall not be required to report and enter on

arrival in the Philippines, unless engaged in the transportation of

merchandise in the way of trade.'

"The term 'report and enter' appearing in the last paragraph of

Section 1221 means, according to the Collector of Customs, 'the

entrance of a vessel from a foreign port into a Philippine port of

entry as contemplated in Section 1225' which reads in part:

'SEC. 1225. Documents to be produced by master upon entry of

vessel.For the purpose of making entry of a vessel engaged in

foreign trade, the master thereof shall present the following

documents, duly certified by him, to the boarding officer of

customs.

'(a) The original manifest of all cargo destined for the port, to

be returned with boarding officer's indorsement.

*******

878

878 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

"And Section 1228 provides:

'SEC. 1228. Manifest required of vessel from foreign port.Every

vessel from a foreign port or place must have on board complete

written or typewritten manifests of all her cargo.

'All of the cargo intended to be landed at a port in the

Philippines must be described in separate manifests for each port

of call therein. Each manifest shall include the port of departure

and the port of delivery with the marks, numbers, quantity, and

description of the packages and the names of the consignees

thereof. Every vessel from a foreign port or place must have on

board complete manifests of passengers, immigrants, and their

baggage, in the prescribed form, setting forth their destination

and all particulars required by the immigration laws; and every

such vessel shall have prepared for presentation to the proper

customs official upon arrival in ports of the Philippines a complete

list of all ship's stores then on board. If the vessel does not carry

cargo, passengers, or immigrants, there must still be a manifest

showing that no cargo is carried from the port of departure to the

port of destination in the Philippines.

'A cargo manifest shall in no case be changed or altered, except

after entry of the vessel, by means of an amendment by the

master, consignee, or agent thereof, under oath, and attached to

the original manifest.' "

One, if not the main, reason given by the Court of Tax

Appeals in holding that the RPS "MISAMIS ORIENTAL"

was not required to present any manifest to the customs

authorities upon its arrival in Manila was that Sections

1221, 1225 and 1228 of the Administrative Code

aforequoted are found under Article VI of the Customs

Law, the title of which reads: "Entrance of vessels in

foreign trade"; that the said article lays down rules

governing entry of vessels engaged in foreign trade; and

that inasmuch as the navy vessel in question was not

engaged in f oreign trade it was not required to submit the

manifest provided for in section 1225. The Tax Court took

the view that under said Article VI of the Customs Law

including the different sections of the Administrative Code

under it, only vessels engaged in foreign trade are required

to submit manifests upon entering any Philippine port. The

Tax Court apparently

879

VOL. 105, MAY 29, 1959 879

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

overlooked the reason behind the requirement of

presenting a manifest and allowed itself to be swayed by

the title of the law. Resort to the title of a statute as an aid

in interpretation thereof is an unsafe criterion, and is not

entitled to much weight. (50 Am. Jur. 301). The title can be

resorted to as an aid where there is doubt as to the

meaning of the law or the intention of the legislature in

enacting it, not otherwise.

The Tax Court also overlooked or failed to give due

consideration to the provisions of Section 1228 which

requires that every vessel from a foreign port or place must

have on board complete written or typewritten manifests of

all her cargoes. Said provision is quite comprehensive, if

not all inclusive, with the exception perhaps of vessels

mentioned in the second paragraph of Section 1221,

namely, war vassels or vessels employed by any foreign

government. This is presumably out of international

practice. In our opinion all other vessels coming from

foreign ports, whether or not engaged in foreign trade,

arriving or touching upon any port in the Philippines

should be provided with a manifest which must be

presented to the customs authorities. The reason for

requiring a manifest is well stated in the brief for the

Commissioner of Customs which we quote with favor:

"Whether the vessel be engaged in foreign trade (Sections 1221

and 1225, Revised Administrative Code) or not (Section 1228),

and even when the vessel belongs to the army or the navy

(Section 1234), the universal requirement from a reading of all

the foregoing provisions is that they be provided with a manifest.

The reason is obvious, and must stem from marine experience. As

the name of the document suggests, a manifest is obviously meant

to place beyond doubt the nature of the load or of the cargo that a

vessel carries. The manifest is therefore intended to be an

indication, if not an open declaration, that the vessel is not

engaged in smuggling or in surreptitious practices and activities

If the making of a manifest were to be a monopoly of vessels

engaged in foreign trade, it is plain that other vessels would be

understood as licensed to engage in undesirable marine activities,

a consequence so absurd as to need no further explanation."

880

880 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

The reason for requiring a manifest in the United States is

also stated in the case of U.S. vs. Sischo, 262 U.S. 165:

"The collection of duties is not the only purpose of a manifest, as

is shown by the requirement of one for outward-bound cargoes

and from vessels in the coasting trade bound for a port in another

collection * * * A government wants to know, without being put to

a search, what articles are brought into the country, and to make

up its own mind not only what duties it will demand, but whether

it will allow the goods to enter at all. It would seem strange if it

should except from the manifest demanded those things about

which it has the greatest need to be informed,if in that one case

it should take a chance of being able to find what it forbids to

come in, without requiring the master to tell what he knows. It

would seem doubly strange when, at the same time, it required

any other person who had knowledge that the forbidden article

was on the vessel to report the fact to the master." 19 USCA. p.

821.

Were we to confine the requirement about the preparation

and presentation of a manifest to vessels engaged in

foreign trade, what about private vessels, yachts, pleasure

boats or cruisers or steamships on a world cruise for

tourists, and ships chartered for a special mission or

purpose, all of which though not engaged in foreign trade,

nevertheless could bring into the country not only dutiable

goods, but also articles of prohibited importation ? The

customs laws could not have intended to exempt all these

vessels from the requirement to present a manifest. Then

we have Section 1234 of the Revised Administrative Code

which we quote below:

"SEC. 1234. Entry of transport or supply ships of the United States

Army or Navy.The master or other officer in charge of a

transport or supply ship of the United States Army or Navy,

arriving from a foreign port at any port in the Philippines, shall,

for the purpose of making entry of his vessel, present a manifest

in duplicate, containing the following information, duly certified

by him to the boarding officer or collector of customs:

"(a) A list of all supplies of the United States Government, for

use of the Army, Navy, or Public Health Service, or of the

Government of the Republic of the Philippines.

"(b) A list of all property of officers and enlisted men aboard,,

or of civilians carried as passengers.

881

VOL. 105, MAY 29, 1959 881

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

"(c) A list of all other goods, wares, merchandise, or effects on

board.

"(d) A list of all passengers on board, other than enlisted men

of the Army, Navy, or other department of service, giving

the name, sex, age, occupation, status, or rank, last

permanent residence, port of embarkation, and

destination, of each such passenger. The number of

enlisted men on board should be stated, giving their

designation, regiment, or department."

In connection with this legal provision above quoted, the

Commissioner of Customs in his decision appealed to the

Court of Tax Appeals said the following:

"* * *. Even before our country attained its independence, and

while the United States sovereignty was supreme over the

Philippines, the master or other officers in charge of a transport

or supply ship of the United States Army and Navy was required

by law (Sec. 1234 of the Revised Administrative Code) to present

to the boarding officer or the Collector of Customs, a duly certified

manifest in duplicate, containing, among others, a list of all

properties of officers and enlisted men, or of civilians carried as

passengers, and a list of all other goods, wares, merchandise, or

effects on board. To sustain the proposition that vessels owned by

the government are not within the pale of the customs laws and

regulations is not only absurd but also fraught with serious

implications, for the irony thereof is that such vessels may bring,

unhampered, into this country dutiable and/or prohibited

merchandise and goods, or, to state it bluntly, they may engage in

the very activity which they are called upon to prevent and

suppress."

But the Court of Tax Appeals equally held that Section

1234 is not applicable to vessels of the Philippine Navy . for

the reason that said section applies only to ships of the

United States Army or Navy, and that if our legislature

had really wanted or intended to make its provisions

applicable to our navy ships, it should have made the

corresponding change or amendment of the section. We

agree that it should have been done. But we believe that

there was no necessity where as in the present case the

application of said section to our navy ships is so clear and

manifest, considering that the reasons for requiring a

manifest from transport and supply ships of the army and

navy of the United States are and with more reason

applicable to our navy ships to carry out

882

882 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

the policy of the government, and because we have

complete control over them.

We therefore believe and hold that the RPS "MISAMIS

ORIENTAL" was required to present a manifest upon its

arrival in Manila on September 2, 1954.

The Court of Tax Appeals, however, believed and found

that even if a manifest were required of the RPS

"MISAMIS ORIENTAL", still, one was actually presented

by one of its officers to customs authorities through one Mr.

Casimiro de la Ysla on September 3, 1954. This, Ysla

denied. And after carefully studying the evidence on record

and considering the circumstances attending the case, we

are inclined to agree with the Collector of Customs and the

Commissioner of Customs who upheld him that no such

manifest required by law was submitted to the customs

authorities upon the arrival of the RPS "MISAMIS

ORIENTAL".

If a manifest had really been delivered to the customs

authorities upon the arrival of the RPS "MISAMIS

ORIENTAL" there was no reason whatsoever for Ysla to

deny receipt thereof; and there would have been no

occasion or reason for the Acting Collector of Customs on

September 17, 1954 to write to the Chief of Staff of the

Armed Forces of the Philippines stating that according to

his information "a copy of the ship's manifest covering said

cargo had been secured by that office from the

Commanding Officer of the vessel" and request that two

copies thereof be furnished the Bureau of Customs. Why

should the Bureau of Customs ask for copies of the

manifest if as claimed by the navy authorities such

manifest had already been delivered to them?

Again, it had always been the contention and the belief

of the navy authorities that Philippine navy vessels were

not required to prepare and deliver this manifest upon

their arrival in the Philippines from foreign ports. In fact

there is evidence to the effect that on two different

occasions prior to the arrival of RPS "MISAMIS ORI-

883

VOL. 105, MAY 29, 1959 883

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

ENTAL" on September 2, 1954, Philippine navy vessels

had arrived from abroad with merchandise presumably for

personal use of officers and men of the Philippine navy and

that no manifest had been presented covering said goods,

which goods never went through customs. This belief and

attitude of the Philippine navy authorities is reflected in

the letter of Commodore Francisco, dated October 9, 1954,

answering the letter of inquiry and request of the Acting

Collector of Customs, dated September 17, 1954 wherein he

said:

"In this connection, this Command feels that the pertinent

provisions of the Revised Administrative Code. relative to vessels

coming from foreign ports are not applicable to vessels of the

Philippine Navy as the same are war vessels, exempted under

Section 1221 of said code. If your office holds a contrary opinion, a

clarification of this matter is requested."

With this belief and attitude of the Philippine navy

authorities, it was not likely that a manifest of the goods

carried by the RPS "MISAMIS ORIENTAL" was prepared

on board while the boat was still in Japan, much less was a

copy of the manifest if made, was delivered to customs

authorities.

Furthermore, according to the Commissioner of

Customs, we quote from his decision:

"* * * The record shows that the officers of the RPS 'MISAMIS

ORIENTAL' insistently pleaded for the exemption of their vessel

from customs requirements regarding the presentation of cargo

manifest, perhaps not realizing that laws must be equally

enforcedamong public officers and private citizens alike.

Besides, to accord the vessel with such exceptional privilege may

result in government vessels comprising public trust and duty

and serving two incompatible mastersthe government 011 one

hand, and the taxevader on the other. Thus the Government is

rendered helpless in such cases to prevent its being defrauded of

lawful duties and taxes."

If a manifest had already been prepared by the officers of

the ship, and that a copy thereof had been presented to the

customs, why all this insistence and plea, that they be

excused from and relieved of the duty of pre-

884

884 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

senting a manifest when they were found to be without

one?

Moreover, if said manifest had actually been delivered to

customs authorities upon the arrival of the RPS "MISAMIS

ORIENTAL" in Manila, then in the regular course of things

the customs authorities would have inspected the same,

assessed customs duties on them if found dutiable, or

released them if otherwise. And yet the only time when the

customs authorities learned of the existence of the goods

and merchandise on board the RPS "MISAMIS

ORIENTAL" was when according to the decision of the

Collector of Customs a confidential information was

received in the office of the Port Patrol Division of the

Bureau regarding the presence of commercial goods on

board the RPS "MISAMIS ORIENTAL" and after

interception by the Port Patrol Policeman Consorcio Javier

of a truckload of cases leaving the customs zone from the

navy boat. We further quote from the decision of the

Collector of Customs:

"* * * To verify the truth of this information, Col. Manuel

Turingan, then General Supervisor of the Security Division of the

Bureau of Customs, and Atty. Salvador Mascardo, Chief of the

Investigation Section of the Port Patrol Division, went to Pier 5 on

September 6, 1954 where the Philippine Navy boat mentioned

above was then docked. Upon arrival thereat, they were met by

the Commanding Officer of the above-named vessel, who, when

asked, informed them that there were really commercial goods on

board his ship. When the merchandise were brought to and

examined at the customhouse, they were found to be not covered

by the required cargo manifest, bills of lading, consular invoices,

and Central Bank licenses and release certificates. Hence, the

seizure."

Besides, according to the regulations of the Bureau of

Customs, as well as the practice of that office, when a

vessel arrives from a foreign port, a customs boarding

officer boards the ship and a copy or copies of the cargo

manifests are delivered to him by the master of the vessel,

and he makes a proper indorsement thereof including the

date of delivery to him (boarding officer).

885

VOL. 105, MAY 29, 1959 885

Commissioner of Customs vs. Lt. Col. Relunia

And according to Section 1229 of the Revised

Administrative Code, the master of the vessel shall

immediately mail to the Auditor General a copy of the

cargo manifest properly indorsed by the boarding officer. If

as claimed by the navy authorities, the law about cargo

manifests had been fully complied with and that a copy of

said manifest was delivered to an officer of the Bureau of

Customs who had the duty of indorsing and dating the

same and that a copy thereof had been mailed to the

Auditor General, it was not explained why said navy

authorities failed to produce at the hearing their copy of

said manifest duly indorsed by the boarding officer; neither

did they try to subpoena the Auditor General to produce

the copy which should have been mailed to him. All these

point to the conclusion that no such cargo manifest was

ever delivered to the customs authorities upon the arrival

of the RPS "MISAMIS ORIENTAL".

In conclusion, we hold that all vessels whether private

or government owned, including ships of the Philippine

navy, coming from a foreign port, with the possible

exception of war vessels or vessels employed by any foreign

government, not engaged in the transportation of

merchandise in the way of trade, as provided for in the

second paragraph of Section 1221 of the Revised

Administrative Code, are required to prepare and present a

manifest to the customs authorities upon arrival at any

Philippine port.

In view of the foregoing, the appealed decision of the

Court of Tax Appeals as regards the forfeiture of the

electric range in question is set aside, and the decision of

the Commissioner of Customs affirming that of the

Collector of Customs, as regards the same article is hereby

affirmed. No costs.

Pars, C.J., Bengzon, Reyes, A., Bautista Angelo,

Labrador, Concepcin, and Endencia, JJ., concur.

Decision of the Court of Tax Appeals set aside and the

decision of the Collector of Customs affirmed.

886

886 PHILIPPINE REPORTS ANNOTATED

Movido vs. RFC and the Provincial Sheriff of Samar

Copyright 2017 Central Book Supply, Inc. All rights reserved.

Você também pode gostar

- Commissioner of Customs vs. ReluniaDocumento5 páginasCommissioner of Customs vs. Reluniaelna ocampoAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner of Customs v. ReluniaDocumento5 páginasCommissioner of Customs v. ReluniaCarissa CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner of Customs vs. ReluniaDocumento11 páginasCommissioner of Customs vs. ReluniaMark Stephen ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner of Customs v. ReluniaDocumento5 páginasCommissioner of Customs v. ReluniaAngelica AbalosAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner of Customs Vs Relunia, 105 Phil 875, G.R. No. L-11860, May 29, 1959Documento2 páginasCommissioner of Customs Vs Relunia, 105 Phil 875, G.R. No. L-11860, May 29, 1959Gi NoAinda não há avaliações

- Transpo Chapter 4 - Full TextDocumento76 páginasTranspo Chapter 4 - Full TextNaika Ramos LofrancoAinda não há avaliações

- Study Guide #3Documento6 páginasStudy Guide #3Shinji NishikawaAinda não há avaliações

- En Banc: Petitioners vs. vs. RespondentDocumento6 páginasEn Banc: Petitioners vs. vs. RespondentShairaCamilleGarciaAinda não há avaliações

- 30-GD Commissioner of Customs v. CTA, 224 SCRA 665,671 (1993)Documento2 páginas30-GD Commissioner of Customs v. CTA, 224 SCRA 665,671 (1993)kenedy saetAinda não há avaliações

- Vessel Approaching The Former. - Upon The Arrival in Port of Any Vessel Engaged in Foreign Trade, It Shall BeDocumento7 páginasVessel Approaching The Former. - Upon The Arrival in Port of Any Vessel Engaged in Foreign Trade, It Shall BeALAJID, KIM EMMANUELAinda não há avaliações

- En Banc: Petitioners vs. vs. RespondentDocumento6 páginasEn Banc: Petitioners vs. vs. RespondentShairaCamilleGarciaAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner of Customs vs. Court of Tax AppealsDocumento7 páginasCommissioner of Customs vs. Court of Tax AppealsJay-r Tumamak50% (2)

- Commissioner of Customs vs. Manila Star Ferry Inc.Documento2 páginasCommissioner of Customs vs. Manila Star Ferry Inc.Imelda Lozada100% (2)

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondent Hausermann, Cohn & Fisher Acting Attorney-General HarveyDocumento14 páginasPetitioner Vs Vs Respondent Hausermann, Cohn & Fisher Acting Attorney-General HarveyHans Henly GomezAinda não há avaliações

- Transpo Case Digest Part 2Documento4 páginasTranspo Case Digest Part 2Pipoy AmyAinda não há avaliações

- Transpo CasesDocumento31 páginasTranspo CasescmdelrioAinda não há avaliações

- Asaali vs. Commissioner of Customs December 16 1968Documento12 páginasAsaali vs. Commissioner of Customs December 16 1968Tammy Yah100% (1)

- 90 - NDC v. CADocumento2 páginas90 - NDC v. CAperlitainocencioAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner of Customs Vs CTA DigestDocumento3 páginasCommissioner of Customs Vs CTA DigestRomarie AbrazaldoAinda não há avaliações

- TRANSPO - Macondray and Company Inc. v. Acting Commissioner of CustomsDocumento2 páginasTRANSPO - Macondray and Company Inc. v. Acting Commissioner of CustomsJulius Geoffrey TangonanAinda não há avaliações

- TCC CasesDocumento36 páginasTCC CasesLeaneSacaresAinda não há avaliações

- United States Lines vs. Comm. of CustomsDocumento2 páginasUnited States Lines vs. Comm. of CustomsRhea CalabinesAinda não há avaliações

- Stare DecisisDocumento6 páginasStare DecisisJackRio009Ainda não há avaliações

- Asaali V CommissionerDocumento2 páginasAsaali V CommissionerCarlyn Belle de GuzmanAinda não há avaliações

- Transpo Chapter 4 DigestDocumento13 páginasTranspo Chapter 4 DigestNaika Ramos LofrancoAinda não há avaliações

- Comm. of Customs V Hon. Court of Tax AppealsDocumento3 páginasComm. of Customs V Hon. Court of Tax AppealsMae ThiamAinda não há avaliações

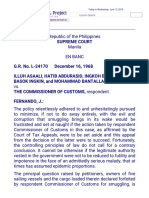

- G.R. No. L-24170 December 16, 1968Documento4 páginasG.R. No. L-24170 December 16, 1968nikoAinda não há avaliações

- Taxation TariffDocumento41 páginasTaxation TariffJp CoquiaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 digestCOMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS V COURT OF TAX APPEALS GR 48886 88Documento3 páginas1 digestCOMMISSIONER OF CUSTOMS V COURT OF TAX APPEALS GR 48886 88Bayombong FireStation Nueva VizcayaAinda não há avaliações

- Schooner Paulina's Cargo v. United States, 11 U.S. 52 (1812)Documento14 páginasSchooner Paulina's Cargo v. United States, 11 U.S. 52 (1812)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Shipping Lines Inc. v. IAC Where It Was Held Under Similar Circumstance "ThatDocumento2 páginasShipping Lines Inc. v. IAC Where It Was Held Under Similar Circumstance "ThatAnn Julienne AristozaAinda não há avaliações

- NDC v. CaDocumento10 páginasNDC v. CaJanicaAinda não há avaliações

- Associated Sugar Inc Et Al Vs Commissioner of Customs Et AlDocumento3 páginasAssociated Sugar Inc Et Al Vs Commissioner of Customs Et AlRyan Jhay YangAinda não há avaliações

- PM1 Week 2Documento4 páginasPM1 Week 2Cb Carl RoscoAinda não há avaliações

- TCC Cases Digests 2014-2015Documento16 páginasTCC Cases Digests 2014-2015praning125Ainda não há avaliações

- Transportation Laws (Maritime Commerce)Documento64 páginasTransportation Laws (Maritime Commerce)Angel Deiparine100% (1)

- National Development Company vs. Court of Appeals and Development Insurance - Surety CorporationDocumento5 páginasNational Development Company vs. Court of Appeals and Development Insurance - Surety CorporationZachary Philipp LimAinda não há avaliações

- Ship MortgageDocumento6 páginasShip MortgageSSAinda não há avaliações

- Stat Con Case Digest XiiDocumento6 páginasStat Con Case Digest XiiDjøn AmocAinda não há avaliações

- Asaali vs. CommissionDocumento3 páginasAsaali vs. CommissionMargeAinda não há avaliações

- TranspoDocumento15 páginasTranspoJDR JDRAinda não há avaliações

- 85 Us Lines V Comm of CustomsDocumento5 páginas85 Us Lines V Comm of CustomsGracia SullanoAinda não há avaliações

- RA 10668 - Cabotage LawDocumento6 páginasRA 10668 - Cabotage LawSa KiAinda não há avaliações

- A Compilation of Digested Cases For Maritime LawDocumento30 páginasA Compilation of Digested Cases For Maritime LawMerGonzagaAinda não há avaliações

- Maritime CommerceDocumento20 páginasMaritime CommercePatrick TanAinda não há avaliações

- ASAALI Vs CUSTOMSDocumento5 páginasASAALI Vs CUSTOMSAnsai CaluganAinda não há avaliações

- Customs Modernization and Tariff Act - Presentation by Atty Randy NagueDocumento44 páginasCustoms Modernization and Tariff Act - Presentation by Atty Randy NaguePortCalls100% (9)

- Tan Chiong Sian Vs InchaustiDocumento5 páginasTan Chiong Sian Vs Inchaustithornapple25100% (1)

- 7107 Islands Shipping Corporation VS Department of FinanceDocumento3 páginas7107 Islands Shipping Corporation VS Department of FinancePaul EsparagozaAinda não há avaliações

- Republic Act No. 10668Documento1 páginaRepublic Act No. 10668Emrico CabahugAinda não há avaliações

- Petitioner-Appellant vs. vs. Respondents Appellees: Second DivisionDocumento9 páginasPetitioner-Appellant vs. vs. Respondents Appellees: Second DivisionNicole HinanayAinda não há avaliações

- Transpo Assigned CasesDocumento60 páginasTranspo Assigned CasesalfieAinda não há avaliações

- CopyrightDocumento2 páginasCopyrightAnonymous B0aR9GdNAinda não há avaliações

- Macondray vs. Commissioner of CustomsDocumento3 páginasMacondray vs. Commissioner of CustomsMaria Jela MoranAinda não há avaliações

- Customs and TariffDocumento54 páginasCustoms and TariffAbegail Protacio GuardianAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. L-24170Documento10 páginasG.R. No. L-24170Amil P. Tan IIAinda não há avaliações

- Commissioner vs. KMK Gani, 182 SCRA 591Documento12 páginasCommissioner vs. KMK Gani, 182 SCRA 591gryffindorkAinda não há avaliações

- PIL 16 - Illuh Asaali Vs CustomsDocumento5 páginasPIL 16 - Illuh Asaali Vs CustomsApril YangAinda não há avaliações

- The immigration offices and statistics from 1857 to 1903: Information for the Universal Exhibition of St. Louis (U.S.A.)No EverandThe immigration offices and statistics from 1857 to 1903: Information for the Universal Exhibition of St. Louis (U.S.A.)Ainda não há avaliações

- (C. Insurable Interest) Tai Tong Chuache & Co. vs. Insurance Commission, 158 SCRA 366, No. L-55397 February 29, 1988Documento8 páginas(C. Insurable Interest) Tai Tong Chuache & Co. vs. Insurance Commission, 158 SCRA 366, No. L-55397 February 29, 1988Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (A. Subject Matter) Blue Cross Health Care, Inc. vs. Olivares, 544 SCRA 580, G.R. No. 169737 February 12, 2008Documento7 páginas(A. Subject Matter) Blue Cross Health Care, Inc. vs. Olivares, 544 SCRA 580, G.R. No. 169737 February 12, 2008Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- Eternal Gardens Memorial Park Corporation, Petitioner, vs. The Philippine American Life Insurance Company, RespondentDocumento10 páginasEternal Gardens Memorial Park Corporation, Petitioner, vs. The Philippine American Life Insurance Company, RespondentAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (B. Parties To The Contract) Valenzuela vs. Court of Appeals, 191 SCRA 1, G.R. No. 83122 October 19, 1990Documento13 páginas(B. Parties To The Contract) Valenzuela vs. Court of Appeals, 191 SCRA 1, G.R. No. 83122 October 19, 1990Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 690 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: Cha vs. Court of AppealsDocumento7 páginas690 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: Cha vs. Court of AppealsQuennie Jane SaplagioAinda não há avaliações

- (A. Subject Matter) United Merchants Corporation vs. Country Bankers Insurance Corporation, 676 SCRA 382, G.R. No. 198588 July 11, 2012Documento16 páginas(A. Subject Matter) United Merchants Corporation vs. Country Bankers Insurance Corporation, 676 SCRA 382, G.R. No. 198588 July 11, 2012Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (A. Subject Matter) Guingon vs. Del Monte, 20 SCRA 1043, No. L-22042 August 17, 1967Documento4 páginas(A. Subject Matter) Guingon vs. Del Monte, 20 SCRA 1043, No. L-22042 August 17, 1967Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (B. Parties To The Contract) Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. vs. Court of Appeals, 316 SCRA 677, G.R. No. 113899 October 13, 1999Documento9 páginas(B. Parties To The Contract) Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. vs. Court of Appeals, 316 SCRA 677, G.R. No. 113899 October 13, 1999Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- Pioneer Insurance & Surety Corporation vs. Court of Appeals: 668 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedDocumento12 páginasPioneer Insurance & Surety Corporation vs. Court of Appeals: 668 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- Delsan Transport Lines, Inc. vs. Court of Appeals: 24 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedDocumento9 páginasDelsan Transport Lines, Inc. vs. Court of Appeals: 24 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (A. Subject Matter) Paramount Insurance Corporation vs. Remondeulaz, 686 SCRA 567, G.R. No. 173773 November 28, 2012Documento6 páginas(A. Subject Matter) Paramount Insurance Corporation vs. Remondeulaz, 686 SCRA 567, G.R. No. 173773 November 28, 2012Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- Rizal Commercial Banking Corporation vs. Court of Appeals: 292 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedDocumento18 páginasRizal Commercial Banking Corporation vs. Court of Appeals: 292 Supreme Court Reports AnnotatedAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (C. Insurable Interest) Gaisano Cagayan, Inc. vs. Insurance Company of North America, 490 SCRA 286, G.R. No. 147839 June 8, 2006Documento11 páginas(C. Insurable Interest) Gaisano Cagayan, Inc. vs. Insurance Company of North America, 490 SCRA 286, G.R. No. 147839 June 8, 2006Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (A. Subject Matter) Malayan Insurance Co., Inc. vs. Regis Brokerage Corp., 538 SCRA 681, G.R. No. 172156 November 23, 2007Documento10 páginas(A. Subject Matter) Malayan Insurance Co., Inc. vs. Regis Brokerage Corp., 538 SCRA 681, G.R. No. 172156 November 23, 2007Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (A. Subject Matter) Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. vs. Prudential Guarantee and Assurance, Inc., 599 SCRA 565, G.R. No. 174116 September 11, 2009Documento13 páginas(A. Subject Matter) Eastern Shipping Lines, Inc. vs. Prudential Guarantee and Assurance, Inc., 599 SCRA 565, G.R. No. 174116 September 11, 2009Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 416 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: Philippine Life Insurance Company vs. PinedaDocumento6 páginas416 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: Philippine Life Insurance Company vs. PinedaJust a researcherAinda não há avaliações

- Palileo vs. Cosio: 920 Philippine Reports AnnotatedDocumento5 páginasPalileo vs. Cosio: 920 Philippine Reports AnnotatedAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 148 Philippine Reports Annotated: El Oriente, Fabrica de Tabacos, Inc., vs. PosadasDocumento4 páginas148 Philippine Reports Annotated: El Oriente, Fabrica de Tabacos, Inc., vs. PosadasAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (C. Insurable Interest) Heirs of Loreto C. Maramag vs. Maramag, 588 SCRA 774, G.R. No. 181132 June 5, 2009Documento9 páginas(C. Insurable Interest) Heirs of Loreto C. Maramag vs. Maramag, 588 SCRA 774, G.R. No. 181132 June 5, 2009Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 10) Rizal Surety & Insurance Co. vs. Manila Railroad Company, 23 SCRA 205, No. L-24043 April 25, 1968Documento4 páginas10) Rizal Surety & Insurance Co. vs. Manila Railroad Company, 23 SCRA 205, No. L-24043 April 25, 1968Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 538 Philippine Reports Annotated: Lampano vs. JoseDocumento4 páginas538 Philippine Reports Annotated: Lampano vs. JoseAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- (C. Insurable Interest) The Insular Life Assurance Company, Ltd. vs. Ebrado, 80 SCRA 181, No. L-44059 October 28, 1977Documento7 páginas(C. Insurable Interest) The Insular Life Assurance Company, Ltd. vs. Ebrado, 80 SCRA 181, No. L-44059 October 28, 1977Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- Federal Express Corporation vs. American Home Assurance CompanyDocumento9 páginasFederal Express Corporation vs. American Home Assurance CompanyAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 8) Fireman's Fund Insurance Company vs. Jamila & Company, Inc., 70 SCRA 323, No. L-27427 April 7, 1976Documento5 páginas8) Fireman's Fund Insurance Company vs. Jamila & Company, Inc., 70 SCRA 323, No. L-27427 April 7, 1976Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 9) F.F. Cruz and Co., Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, 164 SCRA 731, No. L-52732 August 29, 1988Documento6 páginas9) F.F. Cruz and Co., Inc. vs. Court of Appeals, 164 SCRA 731, No. L-52732 August 29, 1988Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 148 Philippine Reports Annotated: El Oriente, Fabrica de Tabacos, Inc., vs. PosadasDocumento4 páginas148 Philippine Reports Annotated: El Oriente, Fabrica de Tabacos, Inc., vs. PosadasAlexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 3) Perez vs. Court of Appeals, 323 SCRA 613, G.R. No. 112329 January 28, 2000Documento7 páginas3) Perez vs. Court of Appeals, 323 SCRA 613, G.R. No. 112329 January 28, 2000Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 12) Oriental Assurance Corporation vs. Ong, 842 SCRA 337, G.R. No. 189524 October 11, 2017Documento19 páginas12) Oriental Assurance Corporation vs. Ong, 842 SCRA 337, G.R. No. 189524 October 11, 2017Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- 5) Zenith Insurance Corporation vs. Court of Appeals, 185 SCRA 398, G.R. No. 85296 May 14, 1990Documento6 páginas5) Zenith Insurance Corporation vs. Court of Appeals, 185 SCRA 398, G.R. No. 85296 May 14, 1990Alexiss Mace JuradoAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 81026. April 3, 1990. Pan Malayan Insurance Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals, Erlinda Fabie and Her Unknown DRIVER, RespondentsDocumento10 páginasG.R. No. 81026. April 3, 1990. Pan Malayan Insurance Corporation, Petitioner, vs. Court of Appeals, Erlinda Fabie and Her Unknown DRIVER, RespondentsJulius AnthonyAinda não há avaliações

- Petitioner Memo Final NUJSDocumento29 páginasPetitioner Memo Final NUJSGurjinder SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Code of Professional ResponsibilityDocumento21 páginasCode of Professional ResponsibilitypoloylocoAinda não há avaliações

- Canon 15 Fajardo Vs BugaringDocumento10 páginasCanon 15 Fajardo Vs BugaringLeomar Despi LadongaAinda não há avaliações

- Empanelment Advocate Uttarakhand 11102022Documento32 páginasEmpanelment Advocate Uttarakhand 11102022Sayantan chakrabortAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial AffidavitDocumento7 páginasJudicial AffidavitDutchsMoin MohammadAinda não há avaliações

- Trans Lifeline Release For TalentDocumento2 páginasTrans Lifeline Release For TalentLogan ToddAinda não há avaliações

- Sign of The Horns Trademark SuitDocumento11 páginasSign of The Horns Trademark SuitPeter PerkowskiAinda não há avaliações

- J. Tiosejo vs. AngDocumento2 páginasJ. Tiosejo vs. AngTrisha VAAinda não há avaliações

- Shidan Gouran Global Blockchain Technologies Global Gaming Defaults in LA CourtDocumento3 páginasShidan Gouran Global Blockchain Technologies Global Gaming Defaults in LA Courtcoindesk2Ainda não há avaliações

- Pinky Anand Arvind Datar Njac CollegiumDocumento12 páginasPinky Anand Arvind Datar Njac CollegiumAnonymous GKlktBAinda não há avaliações

- Purchase of LandDocumento55 páginasPurchase of Landsrinath1234Ainda não há avaliações

- Essay On Indian Judiciary SystemDocumento4 páginasEssay On Indian Judiciary SystemSoniya Omir Vijan67% (3)

- Coronel vs. CapatiDocumento3 páginasCoronel vs. CapatiJustineAinda não há avaliações

- Shashi v. Thirty Three Threads - ComplaintDocumento40 páginasShashi v. Thirty Three Threads - ComplaintSarah BursteinAinda não há avaliações

- Antsand Grasshopper Ex 2012Documento7 páginasAntsand Grasshopper Ex 2012Emily LingAinda não há avaliações

- Outline of A Moot Court ArgumentDocumento2 páginasOutline of A Moot Court Argumentmanuvjohn1989Ainda não há avaliações

- 189 Stronghold V CA (Pintor)Documento2 páginas189 Stronghold V CA (Pintor)Julius ManaloAinda não há avaliações

- LTD 3Documento84 páginasLTD 3JowelYabotAinda não há avaliações

- Heather Jensen Release and Arrest Affidavit PDFDocumento14 páginasHeather Jensen Release and Arrest Affidavit PDFMichael RobertsAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Labor: FECA-PT2Documento719 páginasDepartment of Labor: FECA-PT2USA_DepartmentOfLabor100% (2)

- Calina vs. DBP 1-6Documento13 páginasCalina vs. DBP 1-6MaanAinda não há avaliações

- Judicial Affidavit - Criminal CaseDocumento4 páginasJudicial Affidavit - Criminal CaseRDTuguegaraoAinda não há avaliações

- Agenda Training 18 19 Iunie 2020Documento2 páginasAgenda Training 18 19 Iunie 2020Cristi CîșlaruAinda não há avaliações

- Manila Standard Today - August 25, 2012 IssueDocumento12 páginasManila Standard Today - August 25, 2012 IssueManila Standard TodayAinda não há avaliações

- Bethesda Softworks LLC v. Behaviour Interactive, Inc. and Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.Documento34 páginasBethesda Softworks LLC v. Behaviour Interactive, Inc. and Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.Polygondotcom100% (1)

- Rep Vs GimenezDocumento4 páginasRep Vs Gimenezlou017100% (2)

- De 8-8 Affidavit of J. Noah HageyDocumento14 páginasDe 8-8 Affidavit of J. Noah HageyDaniel FisherAinda não há avaliações

- Microsoft Corp. v. United States, 162 F.3d 708, 1st Cir. (1998)Documento14 páginasMicrosoft Corp. v. United States, 162 F.3d 708, 1st Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Decision: Division (GR NO. 141994, Jan 17, 2005) Filipinas Broadcasting Network V. Ago MedicalDocumento34 páginasDecision: Division (GR NO. 141994, Jan 17, 2005) Filipinas Broadcasting Network V. Ago MedicalJezen Esther PatiAinda não há avaliações

- UTA LawsuitDocumento20 páginasUTA LawsuitTHRAinda não há avaliações