Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Predictors of Quality of Life Among Chinese People With Schizophrenia

Enviado por

windaRQ96Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Predictors of Quality of Life Among Chinese People With Schizophrenia

Enviado por

windaRQ96Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

bs_bs_banner

Nursing and Health Sciences (2016) ,

Research Article

Predictors of quality of life among Chinese people with

schizophrenia

Xiao Qin Wang,1 Marcia A. Petrini1 and Donald E. Morisky2

1

HOPE School of Nursing, Wuhan University, Wuhan, China and 2Department of Community Health Sciences, UCLA Fielding

School of Public Health, Los Angeles, California, USA

Abstract This study was designed to investigate the association of quality of life, perceived stigma, and medication adher-

ence among Chinese patients with schizophrenia, and to ascertain the predictors of quality of life. A cross-

sectional correlation study was conducted with 146 participants. All participants completed self-report scales:

the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale, Links Stigma Scale, and the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale.

Pearson parametric correlations and stepwise multiple regressions were performed. The total quality of life score

and psychosocial subscale was signicantly positively correlated with perceived stigma, coping orientation of

withdrawal, and feelings of stigma, and negatively correlated with age and medication adherence. The means of

all subscale scores except perceived devaluation-discrimination and different/guilty feelings were signicantly

higher than the midpoint of 2.5. The best predictors of quality of life and psychosocial domains were stigma-

related feelings: feeling misunderstood, feeling different/shame, and age. Our ndings suggest that an individuals

negative emotional response may strengthen internalized stigma and decrease quality of life. As the best predictor,

age indicated that adaptation to mental illness may relieve perceived stigma and achieve favorable quality of life.

Key words China, medication adherence, quality of life, schizophrenia, stigma.

INTRODUCTION For 20 years, the effect of mental health on QOL has been

recognized in Mainland China. A community-based program

Schizophrenia is a prevalent and severe mental disorder and was developed to improve mental health, with mental health

may severely impact an individuals quality of life (QOL) hospitals remaining the main provider of care and treatment

(Kao et al. 2011). QOL is the most important measurement (Phillips 2013; Wang et al. 2016). Patients who are clinically sta-

for evaluating outcomes and treatment of people with schizo- ble and scheduled for discharge may face new challenges, such

phrenia, a life-long mental condition, although QOL is a as discrimination and stigma from the public and their family,

multi-dimension concept and has no agreed denition (Awad self-perceived stigma, responsibility for self-medication, and re-

& Voruganti 2012; Boyer et al. 2013). QOL is based on the sidual symptoms and adverse side effects of the medication,

individuals perception of their position in life in the context resulting in relapse or re-hospitalization. Despite these chal-

of culture and value systems (World Health Organization lenges, no current relevant research exists in Mainland China

Quality of Life Group 1998 p551). related to the correlation of QOL, perceived stigma, and med-

Previous studies have revealed multiple contributing factors, ication adherence. The objective of this study was to investigate

such as unemployment and decient nancial resources (Chan (i) the relationship between QOL, perceived stigma, coping

& Yu 2004; Chan et al. 2007); residual symptoms of illness strategies, demographic characteristics, and medication adher-

(Wetherell et al. 2003); public stigma (Lee et al. 2005); internal- ence in people diagnosed with schizophrenia before discharge

ized or perceived stigma (Livingston & Boyd 2010; Tang & Wu from hospital, and (ii) to determine the predictors of QOL.

2012); and side effects of medication and medication adherence

(McCann et al. 2008; Puschner et al. 2009). These interacting

factors affect QOL and may hinder recovery from illness. Cul- METHODS

tural context plays a critical part in evaluating its perception of

individuals life with schizophrenia. Predicting factors remain

understudied in Mainland China. Pioneering research has used DESIGN AND SAMPLE SIZE

global scales to assess patients, which may ignore particular char-

acteristics; therefore, this study used a disease-specic instrument. This study was a cross-sectional correlational design. The sam-

ple size was computed using G* power 3.0 software (Faul et al.

2007). A correlational model was used with a medium effect

size= 0.30, power = 0.80, and alpha = 0.05, in which a total sam-

Correspondence address: Xiao Qin Wang, Faculty of HOPE School of Nursing, Wuhan

University, 115 Donghu Rd, Wuhan, 430071, China. Email: xiaoqin_wang78@163.com ple of 82 participants was needed. The actual sample size was

Received 22 September 2015; revision 15 March 2016; accepted 19 March 2016 146 participants.

2016 John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12286

2 X. Q. Wang et al.

Participants and ethical consideration agree); higher scores indicate greater stigma perception. The

stigma-coping orientation scale included secrecy, withdrawal,

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Wuhan challenging, distancing, and educating (Link et al. 2002).

University and two psychiatric hospitals in central China. A to- Stigma-related feelings evaluate the individuals perception of

tal of 161 potential participants met the inclusion criteria: aged being misunderstood and different from others and ashamed

1865; clinically diagnosed with schizophrenia based on Diag- about illness ( = 0.62 and 0.70, respectively; Link et al. 2002,

nostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; 2004). In this study, Cronbachs alpha of PDD, stigma-related

American Psychiatric Association 1994) criteria; and clinically feeling, and stigma coping scales were 0.89, 0.73, and 0.88,

stable and ready to be discharged to their home or community. respectively.

Patients were excluded from the study if they were co-morbid The Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) is a

with dementia or substance abusers. The purpose of the study universal adherence scale, in which the medication name in

was explained to all participants, and they were informed of each item can be replaced (Morisky et al. 2008). The total

their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. After scores ranged from 0 to 8 and were ranked as low (< 6), me-

signing the consent forms, potential participants were provided dium (6 to < 8) and high adherence (=8). Cronbachs alpha

with self-report scales and questionnaires. Nine refused and six of MMAS is 0.71 in this study.

dropped out of the study, leaving a nal sample of 146; the re- The social-demographic questionnaire included gender, age,

sponse rate was 90.7%. From October 2011 to February 2013, educational level, marital status, employment status, household

the researcher collected data, providing questionnaires to be income per month, age of the initial onset, and duration of

answered independently. If a participant needed assistance, schizophrenia.

could not read, or had blurred vision, the researcher read out

the items to be answered.

Pilot study

Instruments A pilot study to test the reliability of the scale was conducted

before the main study. Thirty participants were eligible based

The Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale (SQLS) developed by on the same inclusion criteria. The internal consistency for

Wilkinson et al. (2000) is a disease-specic measurement for the 30-item SQLS was = 0.85. The subscales of SQLS had

people with schizophrenia to evaluate how their lives are im- the following values: psychosocial dysfunction = 0.89,

pacted. It contains 30 items in three subscales: psychosocial dys- symptom/side effect = 0.79, and dysfunction of

function (15 items), symptom/side effects (8 items), and motivation/energy = 0.69. The internal consistency for the

dysfunction of motivation and energy (7 items). Each item is 46-item Link Stigma Scale was = 0.90. The subscales had the

scored using a ve-point Likert format (0 = never to 4 = al- following values: PDD = 0.88, and stigma coping orientation

ways). Four items (Nos. 12, 13, 15 and 20) are reverse coded scale = 0.87. The MMAS-8 had an internal consistency of

(0 = always to 4 = never). Responses to scales range from 100 = 0.74. Data collected in the pilot study were not included in

reecting the worst QOL to 0 reecting the best. SQLS has the main study.

been reported as having acceptable reliability and validity (Wil-

kinson et al. 2000). The original scale was translated and back- Data analysis

translated by psychiatric professionals. The back-translated

version was sent to the editor of Oxford Outcomes Ltd, who SPSS version 17.0 (IBM Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA) was

suggested changes for some of the items. For example, in item used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated

1, I lack of energy while working was changed to I lack en- for the demographic information. Pearson parametric correla-

ergy while doing things; in item 9, I feel hopeless was tions were performed to explore the relationships between

changed to I feel desperate; in item 14, I am always doing QOL, perceived-stigma, coping orientations, medication ad-

things in the way that people think it is wrong was changed herence, and demographic characteristics. Stepwise multiple

to I misinterpret what people say; in item 20, I feel I can deal regressions were performed to identify the best predictors of

with some things was changed to I think I can cope; in item QOL. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically signicant.

25, I get muscle cramp was changed to I get muscle

twitches; and in item 29, I feel uneasy whenever thinking RESULTS

about the past was changed to I feel upset whenever thinking

about the past. These six items were translated and back- The MMAS socio-demographic information and means and

translated once more, at which time it was agreed that no mis- standard deviation (SD) are presented in Table 1; 47.3% of par-

interpretation remained. Oxford Outcomes Ltd. approved the ticipants were men, 52.7% women. Almost 70% of participants

Chinese version. Cronbachs alpha of the SQLS was 0.89 for were aged between 21 and 40 years; and 68.5% (n = 146) had

this study, and subscales were: psychosocial dysfunction no higher education. The age of initial onset ranged from 14

= 0.90, symptom/side effect = 0.80, and dysfunction of moti- to 25 years, accounting for 65%; 71.3% of the participants were

vation and energy = 0.73. single, divorced, and widowed.

Link et al. (2002) developed Links Stigma Scales, consisting Factors included in the PDD and coping orientation sub-

of three subscales: perceived devaluation-discrimination scales are presented in Table 2. According to Link et al.

(PDD), stigma-coping orientation, and stigma-related feeling. (2002), the mean of each subscale was compared with the 2.5

The scales range from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly midpoints to assess the level of perceived stigma. The means

2016 John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

Quality of life for people with schizophrenia 3

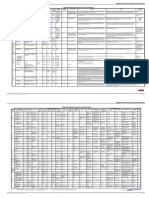

Table 1. Social-demographic characteristics of participants and Table 2. Means and standard deviations of stigma scores and t-test

MMAS (n = 146) compared with 2.5 midpoint (n = 146)

Frequency Percent (%) t-test comparing mean to

2.5 midpoint

Gender

Male 69 47.3 Variables Mean SD t P

Female 77 52.7

Age (years) PDD 2.53 0.43 0.81 0.42

1820 16 11.0 Stigma-coping orientation

2130 61 41.7 Secrecy 2.95 0.48 11.38 0.000**

3140 42 28.8 Withdrawal 2.63 0.37 4.11 0.000**

> 40 27 18.5 Educating 2.83 0.48 8.17 0.000**

Educational level Challenging 2.88 0.44 10.52 0.000**

None or Primary school 10 6.8 Distancing 2.72 0.44 5.96 0.000**

Junior high school 49 33.6 Stigma-related feeling

Senior high school 41 28.1 Misunderstood 2.81 0.44 8.51 0.000**

Technical school/bachelor degree 46 31.5 Different and ashamed 2.32 0.50 -4.48 0.000**

Marital status *

P < 0.05;

Single 82 56.2

**P < 0.01. PDD, perceived devaluation-discrimination; SD, standard

Married/remarried 42 28.7

deviation.

Divorced 19 13.0

Widowed 3 2.1

Employment status before hospitalization correlated with PDD (r = 0.189, P < 0.05; r = 0.193, P < 0.05);

Full-time employment/study 68 46.6

coping orientation of withdrawal (r = 0.197, P < 0.05; r = 0.179,

Part-time employment 14 9.6

Unemployment/ no study 55 37.7

P < 0.05); different and ashamed stigma-related feelings

Retired 9 6.2 (r = 0.243, P < 0.01; r = 0.219, P < 0.01); and misunderstood

Household income per month stigma-related feelings (r = 0.258, P < 0.01; r = 0.284, P < 0.05).

< 1000 Yuan 14 9.6 SQLS and the psychosocial domain were signicantly and neg-

10002000 Yuan 59 40.4 atively correlated with age (r = 0.192, P < 0.05; r = 0.183,

20003000 Yuan 41 28.1 P < 0.05, respectively), and medication adherence (r = 0.185,

> 3000 Yuan 32 21.9 P < 0.05; r = 0.196, P < 0.05, respectively).

Age of initial onset The best predictors of QOL among the variables are pre-

1419 years 37 25.3 sented in Table 4. For SQLS, stigma-related feelings of being

2025 years 58 39.7

misunderstood, difference/shame, and age entered the equa-

2635 years 33 22.6

3645 years 13 8.9

tion at the rst, second, and third steps, respectively, and

45 years and above 5 3.4 accounted for 14.1% (P = 0.000) of the variance. For the psy-

Duration of schizophrenia chosocial domain, misunderstood stigma-related feelings, age,

First episode 16 11.0 and difference/shame stigma-related feeling accounted for

< 1 year 22 15.1 16.1% (P = 0.000) of the variance. For the symptom/side effect

13 years 26 17.8 domain, difference and shame stigma-related feeling explained

35 years 19 13.0 4.2% (P = 0.014) of the variance.

510 years 33 22.6

1015 years 15 10.3

15 years and above 15 10.3 DISCUSSION

MMAS

According to Wilkinson et al. (2000) the means of total SQLS

Low adherence (< 6) 70 47.9

Medium adherence (6 to < 8) 46 31.5

and three subscales are below 40, which implies that patients

High adherence (= 8) 30 20.5 with schizophrenia have a comparatively good QOL before dis-

charge. A plausible explanation for this may be that partici-

MMAS, Morisky Medication Adherence Scale. pants have lower symptom levels and a stable mental status

prior to discharge, indicated by high SQLS scores: 92.5% of

of all subscale scores, except the PDD and different/shame feel- participants reported always or often able to carry out

ing scales, were signicantly higher than the 2.5 midpoint, sug- my day to day activities; over 54.1% feel that I can cope;

gesting that most individuals struggled to cope in various ways and 45.2% take part in enjoyable activities. A possible inter-

to relieve perceived stigma. The coping orientations most fre- pretation of these ndings is that individuals were provided

quently used in this study were secrecy (2.95 0.48) and chal- with opportunities to interact with others in the hospital envi-

lenging (2.88 0.44). ronment and received supportive and therapeutic care from

Correlations between QOL, perceived stigma, coping strate- psychiatric professionals; participation was encouraged in a va-

gies, demographic characteristics, and medication adherence riety of activities provided by nurses or therapists. All of these

are shown in Table 3. SQLS and the psychosocial domain, the factors could facilitate self-evaluation and consequently pro-

dependent variables, were signicantly and positively mote QOL. However, new challenges or difculties awaited

2016 John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

4 X. Q. Wang et al.

Table 3. Correlations among demographic characteristics, SQLS, PDD, coping orientations, and medication adherence (n = 146)

Variables X1 X2 X3 X4 X5 X6 X7 X8 X9 X10 X11 X12 X13 X14 X15

Age (X1) 1 0.597** -0.192* -0.183* -0.108 0.045 0.206* 0.033 0.112 -0.085 -0.209* 0.034 0.071 0.227** -0.051

Duration of 1 -0.076 -0.110 -0.028 0.020 0.280** 0.117 0.200* -0.081 -0.233** 0.047 0.007 0.120 -0.195*

schizophrenia (X2)

SQLS (X3) 1 0.939** 0.721** 0.765** 0.189* 0.081 0.197* -0.012 -0.011 0.036 0.258** 0.243** -0.185*

Psychosocial (X4) 1 0.637** 0.708** 0.193* 0.091 0.179* -0.002 -0.023 0.056 0.284** 0.219** -0.196*

Motivation/energy 1 0.576** 0.085 0.032 0.148 -0.078 -0.026 -0.060 0.082 0.156 -0.081

(X5)

Symptom/side effect 1 0.025 0.042 0.134 0.045 0.046 0.061 0.177* 0.204* -0.121

(X6)

PDD (X7) 1 0.338** 0.168* -0.111 -0.300** -0.066 0.151 0.373** -0.258**

Stigma-coping

orientation

Secrecy (X8) 1 0.395** 0.192* 0.044 0.108 0.297** 0.213* -0.166*

Withdrawal (X9) 1 0.186* 0.111 0.144 0.400** 0.414** -0.136

Educating (X10) 1 0.677** 0.070 0.096 -0.108 0.039

Challenging (X11) 1 0.020 0.075 -0.158 0.082

Distancing (X12) 1 0.389** 0.090 -0.062

Stigma-related

feelings

Misunderstood 1 0.263** -0.079

(X13)

Different and 1 -0.246**

ashamed (X14)

Medication 1

adherence (X15)

*P < 0.05;

**P < 0.01. PDD, perceived devaluation-discrimination; SQLS, Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale.

the participants after discharge. Participants (38.3%) reported Although the PDD subscale means are not signicantly

always, often, or sometimes worry about my future, above the 2.5 midpoints, and the different/shame feelings sub-

while 32.9% always, often, or sometimes nd it difcult scale is even lower than the midpoint, participants still predom-

to mix with people. All of these concerns would impact QOL. inantly report perceived stigma. Over two-thirds (76%)

Our ndings demonstrate that those with poorer QOL per- strongly agreed or agreed that Most people would not hire a

ceived a higher level of stigma and more frequently endorsed former mental patient to take care of their children, even if

withdrawal as a coping strategy. When diagnosed with schizo- he or she had been well for some time, and 60.9% strongly

phrenia, individuals have to face many frustrations, especially agreed, and agreed that Most young women would be reluc-

rejection and discrimination by the public, and withdraw as a tant to date a man who has been hospitalized for a severe men-

coping strategy to avoid rejection, which may result in isolation tal disorder.

from society, less opportunity for employment, and ultimately a Perceived devaluation-discrimination was found to be signif-

lower QOL. Previous ndings reported that high levels of inter- icantly and positively correlated with age and duration of

nalized stigma were correlated with decreased QOL (Switaj schizophrenia, which implies that individuals who are older,

et al. 2009; Livingston & Boyd 2010). with longer disease duration experience a higher level of

Table 4. Predictors of SQLS and subscale (n = 146)

2 2

Dependent Variable Step Predictors R R Adjusted R F P

a

SQLS 1 Misunderstood .258 .067 .060 10.283 .002**

b

2 Difference/ashamed .316 .100 .087 7.922 .001**

c

3 Age .376 .141 .123 7.772 .000**

a

Psychosocial domain 1 Misunderstood .284 .081 .074 12.609 .001**

b

2 Age .349 .122 .110 9.933 .000**

c

3 Difference/ashamed .401 .161 .143 9.095 .000**

a

Symptom/side effect domain 1 Difference/ashamed .204 .042 .035 6.252 .014*

*P < 0.05;

**P < 0.01. SQLS, Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale.

2016 John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

Quality of life for people with schizophrenia 5

stigma. With increasing age expectancies for those with schizo- symptoms and improve QOL on one hand, but its side effects

phrenia, people are more likely to encounter enacted or per- may destroy QOL (Pinikahana et al. 2002; Kuo et al. 2007).

ceived stigma when they are in contact with the community. Puschner et al. (2009) found that QOL was inuenced by adher-

According to modied labeling theory (MLT), they internalize ence at baseline, and affected by symptom severity and side ef-

the stigmatized reaction from others and label themselves as fects of medication at follow-up. No correlation between

mentally ill, leading to an increased expectation of stigma (Link adherence and the symptom/side effect domain of SQLS was

et al. 1989). found in this study. The means and SD of symptom/side effects

Higher levels of perceived stigma result in an increase in (13.09 11.75) were less than other domains, indicative that the

avoidance coping strategies, demonstrated by signicant posi- participants experienced fewer symptoms and side effects. A

tive correlations between PDD and the coping orientation of probable reason may be that psychiatric symptoms were con-

secrecy and withdrawal. Secrecy, to an extent, may be the best trolled by antipsychotic medications and participants were will-

choice to protect individuals against social rejection and com- ing to adhere to the medication because of a gradual recovery

bat stigma when seeking a job or interacting with acquain- of insight. Another suggestion is that the side effects could be

tances. However, concealment of a stigmatized attribute accepted and tolerated related to the choice of antipsychotic

might limit opportunities and social support, and arouse shame, atypical medication. Verication with participants medical re-

resulting in negative self-evaluation and recovery (Ow & Lee cords conrmed that most patients were prescribed atypical an-

2015). Secrecy is one of the most common coping orientations tipsychotics, such as quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone.

and positively correlated with PDD, and in the context of a Chi- Medication adherence was found to be signicantly and neg-

nese population, cultural difference needs to be taken into ac- atively associated with PDD, different/shame feelings, and cop-

count. Chinese traditional cultural values and beliefs are ing via secrecy, implying that a person with higher perceived

strongly inuenced by Confucianism, which deems that pa- stigma inclined toward poorer adherence. Self-stigma was con-

tients have schizophrenia as a result of their own moral failure; sidered a patient-related obstacle for adherence, and even the

therefore, it is understandable that Chinese people with schizo- best predictor of treatment adherence (Fung et al. 2008; Tsang

phrenia suffer from high levels of stigma, related to the idea of et al. 2009). Additionally, the unwanted side effects caused by

face (mianzi) in Chinese society (Lam et al. 2010; Lv et al. antipsychotic medication can make individuals with mental dis-

2013). Face is akin to the notion of reputation in Western orders more easily recognizable and, hence, lead to stigma and

values and is a symbol of social status and identity in Chinese feelings of shame (Lee et al. 2005). Consequently, individuals

social class (Lam et al. 2010; Lv et al. 2013). Unfortunately, a di- adopt secrecy as a strategy for self-protection, which may in-

agnosis of schizophrenia gives rise to a loss of face for the pa- crease non-adherence to medication.

tient, family or even the whole group ; in order to preserve Not only were high levels of different/shame and misunder-

face, a majority of individuals must conceal their mental dis- stood stigma-related feelings correlated with a decrease in the

orders (Yang 2007; Lv et al. 2013). Our ndings are supported total QOL score and the psychosocial and symptom/side effect

by the results of several pioneer studies (Chung & Wong domain, but they were also the best predictors of QOL. This

2004; Lv et al. 2013). nding suggests that feelings of shame might impact the level

Only 20.5% (n = 146) of the participants recorded scores of of perceived stigma. When people with schizophrenia felt mis-

high adherence. Overall, adherence behavior was in the satis- understood, separated, and different from others because of

ed level because 97.9% of the participants in the study re- mental illness, they were angry, embarrassed, ashamed, and

ported: There were no days when I did not take the afraid (Link et al. 2004). These negative emotional responses

prescribed antipsychotics medicine over the past two weeks, would signicantly inuence the internalization of stereotypes

and 100% said they took their medicine yesterday. It is likely into self-evaluation and, invariably, lead to the adoption of

that the participants were in a stable mental state, their aware- avoidant coping orientation (secrecy and withdrawal) to relieve

ness of their illness systematically recovered, and they realized shameful feelings, which may ultimately impact upon capacity

the medication was benecial for them, so were more willing to for social interaction and hinder every aspect of QOL.

adhere to medication. Another explanation may be that strict Age is one of the best predictors of the dependent variables,

management and monitoring in the psychiatric hospital ensures which implies that older age is linked with more favorable psy-

that patients take drugs under surveillance and cannot refuse chosocial QOL. In general, QOL declines when age increases;

prescribed treatment whether willing or not; however, 41.1% however, we found the opposite. A possible explanation may

of participants reported: Sometimes forget to take prescribed be an adaptation to the characteristics of the illness to achieve

pills, and 35.6% feel hassled about sticking to the prescribed relatively better QOL via response shift (Boyer et al. 2013).

antipsychotics treatment plan. This nding is a potential risk With increased age, patients may have had lower expectations

factor for non-adherence after discharge. and sought more efcient ways to attain higher satisfaction

Negative correlations between medication adherence and (Priebe et al. 2010). Another reason may be that the ages of

SQLS and psychosocial domain underlined that an individual the 119 participants (81.5%) in our study were between 18

with higher medication adherence had a better QOL. This nd- and 40; that is, they were in middle adulthood, and their phys-

ing is understandable in that medication can control psychotic ical health was better than that of elderly people. Our nding

symptoms and reduce the likelihood of relapse and re- is supported by the results of previous studies, in that individ-

hospitalization, ultimately improving QOL. Considering the uals with schizophrenia have a lower physical QOL and mild

correlation between medication adherence and SQLS, one cognitive impairment, but have improved psychosocial func-

must recognize that antipsychotic medication could reduce tion with age, because they strive to adapt to the illness,

2016 John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

6 X. Q. Wang et al.

develop effective coping strategies, and increased capacity for REFERENCES

self-management (Folsom et al. 2009; Jeste et al. 2011; Shep- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of

herd et al. 2012). mental disorders (DSM-IV) (4th edn). Washington, DC: American

Several limitations of the study should be considered. The re- Psychiatric Association, 1994.

spondents were recruited from a limited number of psychiatric Awad AG, Voruganti LN. Measuring quality of life in patients

hospitals via purposive sampling; the application of these re- with schizophrenia: An update. Pharmacoeconomics 2012; 30:

sults to people with schizophrenia in other areas of Mainland 183195.

China may be restricted. QOL, perceived stigma, and medica- Boyer L, Baumstarck K, Boucekine M et al. Measuring quality of life

tion adherence are complex concepts inuenced by multiple in patients with schizophrenia: An overview. Expert Rev.

factors, and these variables inuence each other. Thus, rela- Pharmacoecon. Outcomes Res. 2013; 13: 343349.

tionships between the variables may be explained in reverse; Chan SW, Hsiung PC, Thompson DR et al. Health-related quality of life

of Chinese people with schizophrenia in Hong Kong and Taipei: A

for example, an increase in age is associated with more favor-

cross-sectional analysis. Res. Nurs. Health 2007; 30: 61269.

able QOL and correlated with a higher level of perceiving

Chan S, Yu IW. Quality of life of clients with schizophrenia. J. Adv.

stigma; however, a higher level of perceived stigma is corre- Nurs. 2004; 45: 7283.

lated with poorer QOL. Therefore, future studies should be Chung KF, Wong MC. Experience of stigma among Chinese mental

conducted with a larger multi-center or multi-region sample, health patients in Hong Kong. Psychiatr. Bull. 2004; 28: 451454.

using random sampling to improve the accuracy and generaliz- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A et al. G*Power 3: A exible statistical

ability of the results. power analysis program for the social, behavioral and biomedical sci-

ences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007; 39: 175191.

Folsom DP, Depp C, Palmer BW et al. Physical and mental health-

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS related quality of life among older people with schizophrenia.

Schizophr. Res. 2009; 108: 207213.

Signicant evidence-based ndings of Chinese people with Fung KM, Tsang HW, Corrigan PW. Self-stigma of people with schizo-

schizophrenia were obtained: (i) the relationships that exist phrenia as predictor of their adherence to psychosocial treatment.

among the variables of QOL, perceived stigma, and medication Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2008; 32: 95104.

adherence; and (ii) the best predictors of QOL. Misunder- Jeste DV, Wolkowitz OM, Palmer BW. Divergent trajectories of physi-

cal, cognitive, and psychosocial aging in schizophrenia. Schizophr.

standing and difference/shame were predictors of QOL in the

Bull. 2011; 37: 451455.

psychosocial domain, which suggested that a patients negative Kao YC, Liu YP, Chou MK et al. Subjective quality of life in patients

emotional reaction may strengthen internalized stigma and de- with chronic schizophrenia: Relationships between psychosocial

crease QOL. Age was a predictor of QOL and the psychosocial and clinical characteristics. Compr. Psychiatry 2011; 52: 171180.

domain, which underlined that adaptation to illness could re- Kuo PJ, Chen-Sea MJ, Lu RB et al. Validation of the Chinese version of

lieve the perceived stigma and achieve positive QOL. the Schizophrenia Quality of Life Scale Revision 4 (SQLS-R4) in

The results of this study suggest implications for clinical Taiwanese patients with schizophrenia. Qual. Life Res. 2007; 16:

practice. Because community mental health services for people 15331538.

with psychiatric disorders are not well-developed in Mainland Lam CS, Tsang HWH, Corrigan PW et al. Chinese lay theory and

China, psychiatric professionals play a crucial role in assisting mental illness stigma: Implications for research and practices.

J. Rehabil. 2010; 76: 3540.

patients to establish positive self-evaluation and effective

Lee S, Lee MT, Chiu MYet al. Experience of social stigma by people with

coping strategies in order to weaken perceived stigma and feel- schizophrenia in Hong Kong. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005; 186: 153157.

ings of shame (Wang et al. 2016). Mental health professionals Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E et al. A modied labeling theory ap-

mentor patients to adapt gradually to their mental disorder proach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. Am. Sociol.

through a variety of interventions, such as health education, Rev. 1989; 54: 400423.

group activities, and recreation therapy. Knowledge of medica- Link BG, Struening E, Neese-Todd S et al. On describing and seeking

tion provided to patients and family members may improve to change the experience of stigma. Psychiatr. Rehabil. Skills 2002;

medication adherence after discharge. At the same time, 6: 201231.

community-based psychiatric services should be established, Link BG, Yang LH, Phelan JC et al. Measuring mental illness stigma.

and psychiatric professionals should be educated to help pa- Schizophr. Bull. 2004; 30: 511541.

Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized

tients adapt smoothly to society and achieve social

stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review

rehabilitation. and meta-analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010; 71: 21502161.

Lv Y, Wolf A, Wang X. Experienced stigma and self-stigma in Chi-

nese patients with schizophrenia. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2013;

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT 35: 8388.

McCann TV, Boardman G, Clark E et al. Risk proles for non-

We gratefully acknowledge all participants of the study. adherence to antipsychotic medications. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health

Nurs. 2008; 15: 622629.

Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M et al. Predictive validity of a

CONTRIBUTIONS medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J. Clin.

Hypertens. 2008; 10: 348354.

Study design: XQW, PM Ow CY, Lee BO. Relationships between perceived stigma, coping orien-

Data Collection and Analysis: XQW tation, self-esteem, and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia.

Manuscript Writing: XQW, PM, DEM Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2015; 27: 19321941.

2016 John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

Quality of life for people with schizophrenia 7

Phillips MR. Can Chinas new mental health law substantially reduce Tsang HW, Fung KM, Corrigan PW. Psychosocial and socio-

the burden of illness attributable to mental disorders? Lancet 2013; demographic correlates of medication compliance among peo-

381: 19641966. ple with schizophrenia. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 2009;

Pinikahana J, Happell B, Hope J et al. Quality of life in schizophrenia: 40: 314.

A review of the literature from 1995 to 2000. Int. J. Ment. Health Wang XQ, Petrini M, Morisky DE. Comparison of the quality of

Nurs. 2002; 11: 103111. life, perceived stigma and medication adherence of Chinese with

Priebe S, Reininghaus U, McCabe R et al. Factors inuencing subjec- schizophrenia: A follow-up study. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2016;

tive quality of life in patients with schizophrenia and other mental 30: 4146.

disorders: A pooled analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2010; 121: 251258. Wetherell JL, Palmer BW, Thorp SR et al. Anxiety symptoms and qual-

Puschner B, Angermeyer MC, Leese M et al. Course of adherence to ity of life in middle-aged and older outpatients with schizophrenia

medication and quality of life in people with schizophrenia. Psychia- and schizoaffective disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003; 64: 14761482.

try Res. 2009; 165: 224233. Wilkinson G, Hesdon B, Wild D et al. Self-report quality of life measure

Shepherd S, Depp CA, Harris G, Halpain M, Palinkas LA, Jeste DV. for people with schizophrenia: The SQLS. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000; 177:

Perspectives on schizophrenia over the lifespan: A qualitative study. 4246.

Schizophr. Bull. 2012; 38: 295303. World Health Organization Quality of Life Group. Development of the

Switaj P, Wcirka J, Smolarska-Switaj J et al. Extent and predictors of World Health Organiztion WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life As-

stigma experienced by patients with schizophrenia. Eur. Psychiatry sessment. Psychol. Med. 1998; 28: 551558.

2009; 24: 513520. Yang LH. Application of mental illness stigma theory to Chinese socie-

Tang IC, Wu HC. Quality of life and self-stigma in individuals with ties: Synthesis and new directions. Singapore Med. J. 2007; 48:

schizophrenia. Psychiatry Q. 2012; 83: 497507. 977985.

2016 John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

Você também pode gostar

- FNCP Hypertension 1Documento2 páginasFNCP Hypertension 1revita lestariAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal 6Documento13 páginasJurnal 6dewi pspta sriAinda não há avaliações

- ContentServer 3Documento8 páginasContentServer 3Riris KurnialatriAinda não há avaliações

- Stigma and Outcome of Treatment Among Patients With Psychological Disorders and Their AttendersDocumento5 páginasStigma and Outcome of Treatment Among Patients With Psychological Disorders and Their AttendersFathima ZoharaAinda não há avaliações

- Anti Stigma TaiwanDocumento8 páginasAnti Stigma TaiwanLeticia Raquel Pe�a Pe�aAinda não há avaliações

- Indian J Psychiatry Skizo Impact On QoLDocumento12 páginasIndian J Psychiatry Skizo Impact On QoLAnonymous hvOuCjAinda não há avaliações

- Efficacy of Psychological Intervention For Patients With Psoriasis Vulgaris: A Prospective StudyDocumento8 páginasEfficacy of Psychological Intervention For Patients With Psoriasis Vulgaris: A Prospective StudyTeuku FadhliAinda não há avaliações

- Author's Accepted Manuscript: Psychiatry ResearchDocumento24 páginasAuthor's Accepted Manuscript: Psychiatry ResearchbadrulAinda não há avaliações

- Mental HealthDocumento8 páginasMental HealthJohn TelekAinda não há avaliações

- Ser 9 3 240Documento8 páginasSer 9 3 240Catarina C.Ainda não há avaliações

- Quality of Life in Caregivers of Patients With Schizophrenia A Literature ReviewDocumento6 páginasQuality of Life in Caregivers of Patients With Schizophrenia A Literature Reviewgw0q12dxAinda não há avaliações

- Subjective and Objective Caregiver Burden in Parkinson's DiseaseDocumento7 páginasSubjective and Objective Caregiver Burden in Parkinson's Diseasearpit11111Ainda não há avaliações

- Effects of The Nursing Psychoeducation Program On The Acceptance of Medication and Condition-Specific Knowledge of PatientDocumento6 páginasEffects of The Nursing Psychoeducation Program On The Acceptance of Medication and Condition-Specific Knowledge of PatientEric KatškovskiAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S0883941722000905 MainDocumento11 páginas1 s2.0 S0883941722000905 MainReni Tri AstutiAinda não há avaliações

- Diff Erences in Cognitive Function and Daily Living Skills Between Early-And Late-Stage SchizophreniaDocumento8 páginasDiff Erences in Cognitive Function and Daily Living Skills Between Early-And Late-Stage SchizophreniaRenny TjahjaAinda não há avaliações

- Archives of Psychiatric Nursing: Lora Humphrey Beebe, Kathleen Smith, Chad PhillipsDocumento6 páginasArchives of Psychiatric Nursing: Lora Humphrey Beebe, Kathleen Smith, Chad PhillipsArif IrpanAinda não há avaliações

- Ijepr MarchDocumento6 páginasIjepr MarchnandhaAinda não há avaliações

- Journal Presentation: By, R.Angelin Thangam Bot Final YearDocumento50 páginasJournal Presentation: By, R.Angelin Thangam Bot Final YearAarthi ArumugamAinda não há avaliações

- Vassetal 2015Documento9 páginasVassetal 2015njevkoAinda não há avaliações

- Factor Structure Analysis, Validity and Reliability of The Health Anxiety Inventory-Short FormDocumento7 páginasFactor Structure Analysis, Validity and Reliability of The Health Anxiety Inventory-Short FormDenisa IonașcuAinda não há avaliações

- Hanza Wa 2013Documento6 páginasHanza Wa 2013MicciAinda não há avaliações

- Descriptive StatisticsDocumento16 páginasDescriptive StatisticsSaadia TalibAinda não há avaliações

- Vass 2015Documento9 páginasVass 2015Amina LabiadhAinda não há avaliações

- Take Charge Personality As Predictor of Recovery From Eating DisorderDocumento6 páginasTake Charge Personality As Predictor of Recovery From Eating DisorderRokas JonasAinda não há avaliações

- Bodily and Austin Final DraftDocumento29 páginasBodily and Austin Final Draftapi-582011343Ainda não há avaliações

- Occupational Therapy For Inpatients With Chronic Schizophrenia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled TrialDocumento6 páginasOccupational Therapy For Inpatients With Chronic Schizophrenia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled TrialAngela EnacheAinda não há avaliações

- Exploring Risk Factors For Depression Among Older Men Residing in MacauDocumento11 páginasExploring Risk Factors For Depression Among Older Men Residing in MacauaryaAinda não há avaliações

- QOL CopingDocumento10 páginasQOL CopingNisa PradityaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S0165178112006397 MainDocumento6 páginas1 s2.0 S0165178112006397 Mainirene de la cuestaAinda não há avaliações

- Insight, Self-Stigma and PsychosociaDocumento10 páginasInsight, Self-Stigma and PsychosociaJana AlvesAinda não há avaliações

- 08.06.09 - Psychosocial Impact of Dysthymia A Study Among Married PatientsDocumento6 páginas08.06.09 - Psychosocial Impact of Dysthymia A Study Among Married PatientsRiham AmmarAinda não há avaliações

- Epilepsy & Behavior: Shanna M. Guilfoyle, Sally Monahan, Cindy Wesolowski, Avani C. ModiDocumento6 páginasEpilepsy & Behavior: Shanna M. Guilfoyle, Sally Monahan, Cindy Wesolowski, Avani C. ModiJhonny BatongAinda não há avaliações

- Mond 2010klkoojljljlDocumento20 páginasMond 2010klkoojljljlverghese17Ainda não há avaliações

- Adverse Effects of Perceived Stigma On Social Adaptation of Persons Diagnosed With Bipolar Affective DisorderDocumento6 páginasAdverse Effects of Perceived Stigma On Social Adaptation of Persons Diagnosed With Bipolar Affective Disordershah khalidAinda não há avaliações

- Associations of Physical Activity, Screen Time With Depression, Anxiety and Sleep Quality Among Chinese College FreshmenDocumento5 páginasAssociations of Physical Activity, Screen Time With Depression, Anxiety and Sleep Quality Among Chinese College FreshmenReynaldy Anggara SaputraAinda não há avaliações

- KIneski Rad StigmaDocumento8 páginasKIneski Rad StigmanjevkoAinda não há avaliações

- Research Article: Stresses and Disability in Depression Across GenderDocumento9 páginasResearch Article: Stresses and Disability in Depression Across GenderWaleed RehmanAinda não há avaliações

- Correlates of General Quality of Life Are Different in Patients With Primary Insomnia As Compared To Patients With Insomnia and Psychiatric ComorbidityDocumento13 páginasCorrelates of General Quality of Life Are Different in Patients With Primary Insomnia As Compared To Patients With Insomnia and Psychiatric ComorbidityVictor CarrenoAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation On The Quality of Life of Hemodialysis Patients in IranDocumento7 páginasThe Impact of Multidisciplinary Rehabilitation On The Quality of Life of Hemodialysis Patients in IranDewi KusumastutiAinda não há avaliações

- NIH Public AccessDocumento15 páginasNIH Public AccessSofía SciglianoAinda não há avaliações

- Insight and Symptom Severity in An Inpatient Psychiatric SampleDocumento12 páginasInsight and Symptom Severity in An Inpatient Psychiatric SamplealejandraAinda não há avaliações

- Shukla-Rishi2018 Article HealthLocusOfControlPsychosociDocumento8 páginasShukla-Rishi2018 Article HealthLocusOfControlPsychosociMarie McFressieAinda não há avaliações

- Long-Term Follow-Up Ofthe Tips Early Detection in Psychosisstudy:Effectson 10-YearoutcomeDocumento7 páginasLong-Term Follow-Up Ofthe Tips Early Detection in Psychosisstudy:Effectson 10-YearoutcomeELvine GunawanAinda não há avaliações

- WilianDocumento8 páginasWilianĐỗ Văn ĐứcAinda não há avaliações

- LR EthicsDocumento3 páginasLR EthicsUsman DostAinda não há avaliações

- A Systematic Review and Psychometric Evaluation of Self-Report HoardingDocumento45 páginasA Systematic Review and Psychometric Evaluation of Self-Report HoardingAmita GoyalAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S0022395622000103 MainDocumento9 páginas1 s2.0 S0022395622000103 MainFachry RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Occupational Therapy and Mental Health 1Documento18 páginasOccupational Therapy and Mental Health 1Roman -Ainda não há avaliações

- Ijerph 18 04746Documento10 páginasIjerph 18 04746Arif IrpanAinda não há avaliações

- Multiple Outcome Parameters: A 10 Year Follow-Up Study of First-Episode SchizophreniaDocumento7 páginasMultiple Outcome Parameters: A 10 Year Follow-Up Study of First-Episode SchizophreniadianaAinda não há avaliações

- Manuscrip 2 PDFDocumento41 páginasManuscrip 2 PDFayu purnamaAinda não há avaliações

- Recurrent MiscarriageDocumento5 páginasRecurrent MiscarriagedindaAinda não há avaliações

- Guia EsquizoDocumento8 páginasGuia EsquizoSeleccion PersonalAinda não há avaliações

- Cambios de Personalidad y Personalidad Como Predictor Del Cambio en PsicoterapiaDocumento23 páginasCambios de Personalidad y Personalidad Como Predictor Del Cambio en PsicoterapiaLaboratorio CuantiAinda não há avaliações

- The Factors Associated With Depression in Schizophrenia Patients: The Role of Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, Hope and ResilienceDocumento14 páginasThe Factors Associated With Depression in Schizophrenia Patients: The Role of Self-Efficacy, Self-Esteem, Hope and ResilienceArif IrpanAinda não há avaliações

- Family Interventions For Bipolar DisorderDocumento3 páginasFamily Interventions For Bipolar DisorderRanda NurawiAinda não há avaliações

- The Impact of Infertility On The Psychological Well-Being, Marital Relationships, Sexual Relationships, and Quality of Life of Couples: A Systematic ReviewDocumento17 páginasThe Impact of Infertility On The Psychological Well-Being, Marital Relationships, Sexual Relationships, and Quality of Life of Couples: A Systematic ReviewAnaAinda não há avaliações

- 01 Taylor-Rodgers Evaluation of An Online 2014Documento7 páginas01 Taylor-Rodgers Evaluation of An Online 2014sushmita bhartiaAinda não há avaliações

- Cultivating Empathy For The Mentally Ill Using Simulated Auditory HallucinationsDocumento4 páginasCultivating Empathy For The Mentally Ill Using Simulated Auditory HallucinationsGloria Carbajal ZegarraAinda não há avaliações

- Asian Journal of Psychiatry: Vijeta Kushwaha, Koushik Sinha Deb, Rakesh K. Chadda, Manju MehtaDocumento3 páginasAsian Journal of Psychiatry: Vijeta Kushwaha, Koushik Sinha Deb, Rakesh K. Chadda, Manju MehtaLaumart HukomAinda não há avaliações

- Hearing Voices: Qualitative Inquiry in Early PsychosisNo EverandHearing Voices: Qualitative Inquiry in Early PsychosisAinda não há avaliações

- Nihms 463562Documento16 páginasNihms 463562windaRQ96Ainda não há avaliações

- Feeding of Infants and Young Children in Tsunami Affected Villages in PondicherryDocumento4 páginasFeeding of Infants and Young Children in Tsunami Affected Villages in PondicherrywindaRQ96Ainda não há avaliações

- Ijerph 09 03384Documento14 páginasIjerph 09 03384windaRQ96Ainda não há avaliações

- Adhesive Capsulitis of The Shoulder and Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of PrevalenceDocumento9 páginasAdhesive Capsulitis of The Shoulder and Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of PrevalencewindaRQ96Ainda não há avaliações

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocumento18 páginasNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptwindaRQ96Ainda não há avaliações

- Afhs0501 0004 PDFDocumento10 páginasAfhs0501 0004 PDFwindaRQ96Ainda não há avaliações

- Group Medical Visits (GMVS) in Primary Care: An RCT of Group-Based Versus Individual Appointments To Reduce Hba1C in Older PeopleDocumento10 páginasGroup Medical Visits (GMVS) in Primary Care: An RCT of Group-Based Versus Individual Appointments To Reduce Hba1C in Older PeoplewindaRQ96Ainda não há avaliações

- Dr. Lamia El Wakeel, PhD. Lecturer of Clinical Pharmacy Ain Shams UniversityDocumento19 páginasDr. Lamia El Wakeel, PhD. Lecturer of Clinical Pharmacy Ain Shams UniversitysamvetAinda não há avaliações

- Sickle-Cell AnemiaDocumento11 páginasSickle-Cell Anemiahalzen_joyAinda não há avaliações

- Care Plan - Chronic PainDocumento4 páginasCare Plan - Chronic Painapi-246639896Ainda não há avaliações

- Ethics Uworld NotesDocumento3 páginasEthics Uworld NotesActeen MyoseenAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Iron Poisoning - PharmacologyDocumento10 páginasAcute Iron Poisoning - PharmacologyAmmaarah IsaacsAinda não há avaliações

- Agent CharacteristicsDocumento2 páginasAgent Characteristicsyiaili1234100% (1)

- Reproductive Tract InfectionDocumento48 páginasReproductive Tract InfectionSampriti Roy100% (1)

- Cue and Clue Problem List and Initial Diagnosis PlanningDocumento3 páginasCue and Clue Problem List and Initial Diagnosis PlanningWilujeng AnggrainiAinda não há avaliações

- AWES Question Papers For Home ScienceDocumento5 páginasAWES Question Papers For Home ScienceAtul SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Index Case Presentation: TuberculosisDocumento14 páginasIndex Case Presentation: Tuberculosisnandini singhAinda não há avaliações

- ADA Cal en DT ADS001150 Rev01Documento1 páginaADA Cal en DT ADS001150 Rev01vijayramaswamyAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology of HypertensionDocumento54 páginasPathophysiology of HypertensionKaloy Kamao100% (3)

- Low Blood Pressure (Hypotension) Lifestyle Mayo ClinicDocumento8 páginasLow Blood Pressure (Hypotension) Lifestyle Mayo ClinicanupamrcAinda não há avaliações

- RPHC4004 Fashion Constructed Image: AgoraphobiaDocumento51 páginasRPHC4004 Fashion Constructed Image: Agoraphobiacstanhope01Ainda não há avaliações

- Evaluation and Management of Shock States: Hypovolemic, Distributive, and Cardiogenic ShockDocumento17 páginasEvaluation and Management of Shock States: Hypovolemic, Distributive, and Cardiogenic ShockMarest AskynaAinda não há avaliações

- Hypersensitivity ReactionsDocumento12 páginasHypersensitivity Reactionsella Sy100% (1)

- k.21 Dry PleurisyDocumento14 páginask.21 Dry PleurisyWinson ChitraAinda não há avaliações

- Using and Interpreting Stressscan: Envisia Learning 3435 Ocean Park BLVD, Suite 203Documento64 páginasUsing and Interpreting Stressscan: Envisia Learning 3435 Ocean Park BLVD, Suite 203Rajen DhariniAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study LTCSDocumento5 páginasCase Study LTCSKimAinda não há avaliações

- Acid-Base Made EasyDocumento14 páginasAcid-Base Made EasyMayer Rosenberg100% (10)

- Lecture. Physiotherapists. TumoursDocumento34 páginasLecture. Physiotherapists. TumoursdivinaAinda não há avaliações

- Pneumatic RetinopexyDocumento10 páginasPneumatic RetinopexySilpi HamidiyahAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar: DiagnosisDocumento14 páginasSeminar: DiagnosisyenyenAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Nursing RMDocumento11 páginasMedical Nursing RMSharon BaahAinda não há avaliações

- Breast Cancer PresentationDocumento52 páginasBreast Cancer Presentationapi-341607639100% (1)

- Vedic Astrology For Better HealthDocumento27 páginasVedic Astrology For Better HealthJason MintAinda não há avaliações

- Case Presentation: Infective EndocarditisDocumento13 páginasCase Presentation: Infective EndocarditisHillaryAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing CS Acute-Kidney-Injury 04Documento1 páginaNursing CS Acute-Kidney-Injury 04Mahdia akterAinda não há avaliações

- Advances in Detection of Fastidious Bacteria - From Microscopic Observation To Molecular BiosensorsDocumento54 páginasAdvances in Detection of Fastidious Bacteria - From Microscopic Observation To Molecular BiosensorsmotohumeresAinda não há avaliações