Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

SSMJ Vol 6 1 Tuberculosis PDF

Enviado por

LiviliaMiftaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

SSMJ Vol 6 1 Tuberculosis PDF

Enviado por

LiviliaMiftaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

SSMJ Vol 6. No 1. February 2013 Downloaded from www.southsudanmedicaljournal.

com

Main Articles

Tuberculosis 2: Pathophysiology and

microbiology of pulmonary tuberculosis

Robert L. Serafino Wania MBBS, MRCP, MSc (Trop Med)

Pathophysiology mount an effective CMI response and tissue repair leads to

Inhalation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis leads to one of progressive destruction of the lung. Tumour necrosis factor

four possible outcomes: (TNF)-alpha, reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates

and the contents of cytotoxic cells (granzymes, perforin)

• Immediate clearance of the organism

may all contribute to the development of caseating

• Latent infection necrosis that characterize a tuberculous lesion.

• The onset of active disease (primary disease) Unchecked bacterial growth may lead to

• Active disease many years later (reactivation haematogenous spread of bacilli to produce disseminated

disease). TB. Disseminated disease with lesions resembling millet

Among individuals with latent infection, and no seeds is termed miliary TB. Bacilli can also spread by

underlying medical problems, reactivation disease occurs erosion of the caseating lesions into the lung airways -and

in 5 to 10 percent of cases [1]. The risk of reactivation the host becomes infectious to others. In the absence of

is markedly increased in patients with HIV [2]. These treatment, death ensues in 80 per cent of cases [3]. The

outcomes are determined by the interplay of factors remaining patients develop chronic disease or recover.

attributable to both the organism and the host. Chronic disease is characterized by repeated episodes of

healing by fibrotic changes around the lesions and tissue

Primary disease

breakdown. Complete spontaneous eradication of the

Among the approximately 10 per cent of infected bacilli is rare.

individuals who develop active disease, about half will do

so within the first two to three years and are described as Reactivation disease

developing rapidly progressive or primary disease. Reactivation TB results from proliferation of a

The tubercle bacilli establish infection in the lungs after previously dormant bacterium seeded at the time of the

they are carried in droplets small enough (5 to 10 microns) primary infection. Among individuals with latent infection

to reach the alveolar spaces. If the defense system of the and no underlying medical problems, reactivation disease

host fails to eliminate the infection, the bacilli proliferate occurs in 5 to 10 per cent [1]. Immunosuppression is

inside alveolar macrophages and eventually kill the associated with reactivation TB, although it is not clear

cells. The infected macrophages produce cytokines and what specific host factors maintain the infection in a latent

chemokines that attract other phagocytic cells, including state and what triggers the latent infection to become

monocytes, other alveolar macrophages and neutrophils, overt. See previous article [4] for immunosuppressive

which eventually form a nodular granulomatous structure conditions associated with reactivation TB. The disease

called the tubercle. If the bacterial replication is not process in reactivation TB tends to be localized (in

controlled, the tubercle enlarges and the bacilli enter local contrast to primary disease): there is little regional lymph

draining lymph nodes. This leads to lymphadenopathy, node involvement and less caseation. The lesion typically

a characteristic clinical manifestation of primary occurs at the lung apices, and disseminated disease is

tuberculosis (TB). The lesion produced by the expansion unusual unless the host is severely immunosuppressed. It

of the tubercle into the lung parenchyma and lymph node is generally believed that successfully contained latent TB

involvement is called the Ghon complex. Bacteremia may confers protection against subsequent TB exposure [5]

accompany initial infection. Microbiology

The bacilli continue to proliferate until an effective M.tuberculosis (MTB) belongs to the genus Mycobacterium

cell-mediated immune (CMI) response develops, usually that includes more than 80 other species. Tuberculosis

two to six weeks after infection. Failure by the host to (TB) is defined as a disease caused by members of the M.

tuberculosis complex, which includes the tubercle bacillus

a Specialist Trainee in Infectious Diseases & Medical Microbiology/ (M. tuberculosis), M. bovis, M. africanum, M. microti, M.

Virology, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK.

robertserafino@doctors.org.uk canetti, M. caprae and M. pinnipedi [6].

South Sudan Medical Journal 10 Vol 6. No 1. February 2013

SSMJ Vol 6. No 1. February 2013 Downloaded from www.southsudanmedicaljournal.com

MAIN ARTICLES

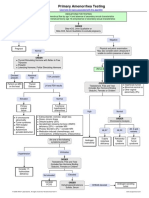

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of tuberculosis

Reproduced with permission from ‘Immune responses to tuberculosis in developing countries: implications for new vaccines’ by Graham A. W. Rook,

Keertan Dheda, Alimuddin Zumla in Nature Reviews Immunology published by Nature Publishing Group Aug 1, 2005

Cell envelope: The mycobacterial cell envelope is The generation time of TB is approximately 12-18 hours,

composed of a core of three macromolecules covalently so that cultures must be incubated for three to six weeks at

linked to each other (peptidoglycan, arabinogalactan, and 370C until proliferation becomes microscopically visible.

mycolic acids) and a lipopolysaccharide, lipoarabinomannan [9] Broth-based culture systems to improve the speed and

(LAM), which is thought to be anchored to the plasma sensitivity of detection have been developed [10]. In AFB

membrane [7]. smear-positive specimens, the BACTEC system can detect

Staining characteristics: The cell wall components M. tuberculosis in approximately eight days (compared to

give mycobacteria their characteristic staining properties. approximately 14 days for smear-negative specimens

The organism stains positive with Gram’s stain. The [11,12].

mycolic acid structure confers the ability to resist destaining Drug sensitivity testing: Drug sensitivity testing is

by acid alcohol after being stained by certain aniline dyes, increasingly important with the emergence of increasingly

leading to the term acid fast bacillus (AFB). Microscopy more resistant M. tuberculosis isolates. In addition to the

to detect AFB (using Ziehl-Neelsen or Kinyoun stain) conventional methods to test M. tuberculosis drug sensitivity,

is the most commonly used procedure to diagnose TB; methods that rely on automated systems and PCR-based

a specimen must contain at least 10 [5] colony forming tests have been developed [13,14]. The microscopic

units (CFU)/mL to yield a positive smear [8]. Microscopy observation drug sensitivity (MODS) test is another liquid

of specimens stained with a fluorochrome dye (such as culture drug-sensitivity test based on observation of M.

auramine O) provides an easier, more efficient and more tuberculosis growth in liquid broth medium containing a

sensitive alternative. However, microscopic detection of test drug. In an evaluation of 3,760 sputa samples using

mycobacteria does not distinguish M. tuberculosis from MODS, automated MB/BacT system, and Löwenstein-

non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Jensen culture, sensitivity was 98, 89, and 84 percent

Growth characteristics: MTB are aerobes. Their respectively and the median time to the test results was

reproduction is enhanced by the presence of 5-10% CO2 7, 22, and 68 days respectively [15]. The Xpert MTB/RIF

in the atmosphere. They are grown on culture media with is an integrated system that combines sample preparation

high lipid content, e.g. Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium. in a modular cartridge system and real-time PCR. In 2010

South Sudan Medical Journal 11 Vol 6. No 1. February 2013

SSMJ Vol 6. No 1. February 2013 Downloaded from www.southsudanmedicaljournal.com

MAIN ARTICLES

this technique was recommended by the WHO to be used 9. Kent, PT, Kubica, GP. Public health mycobacteriology:

in place of traditional smear microscopy for the diagnosis A guide for the level III laboratory. Centers for Disease

of drug-resistant TB or TB in HIV-infected patients [16]. Control, US PHS. 1985.

This test has been shown to have a sensitivity of greater 10. Hanna, BA. Diagnosis of tuberculosis by microbiologic

than 98 per cent in sputum smear-positive TB cases and 75 techniques. In: Tuberculosis, Rom, WN, Garay, S (Eds),

to 90 per cent in smear-negative TB cases. The sensitivity Little, Brown, Boston 1995

in the detection of rifampicin resistant MTB exceeded 11. Roberts GD, Goodman NL, Heifets L, et al. Evaluation

97 per cent, while specificity ranged 98 to 100 per cent. of the BACTEC radiometric method for recovery

The test can yield results in less than two hour [17-19]. of mycobacteria and drug susceptibility testing of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis from acid-fast smear-

Here rifampicin resistance is assessed as a surrogate for

positive specimens. J Clin Microbiol 1983; 18:689.

multidrug resistant MTB.

12. Morgan MA, Horstmeier CD, DeYoung DR, Roberts

Conclusion GD. Comparison of a radiometric method (BACTEC)

South Sudan faces huge challenges in controlling and conventional culture media for recovery of

tuberculosis. This is partly due to a limited laboratory mycobacteria from smear-negative specimens. J Clin

Microbiol 1983; 18:384.

network and lack of a tuberculosis reference laboratory

(author’s observation). 13. Canetti G, Rist N, Grosset J. Measurement of sensitivity

of the tuberculous bacillus to antibacillary drugs by

References the method of proportions. Methodology, resistance

1. Comstock GW. Epidemiology of tuberculosis. Am Rev criteria, results and interpretation. Rev Tuberc Pneumol

Respir Dis 1982; 125:8. (Paris) 1963; 27:217.

2. National action plan to combat multidrug-resistant 14. Canetti G, Froman S, Grosset J, Et Al. Mycobacteria:

tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep 1992; 41:5. Laboratory Methods For Testing Drug Sensitivity And

3. Barnes HL, Barnes, IR. The duration of life in Resistance. Bull World Health Organ 1963; 29:565.

pulmonary tuberculosis with cavity. Am Rev Tuberculosis 15. Moore DA, Evans CA, Gilman RH, et al. Microscopic-

1928; 18:412. observation drug-susceptibility assay for the diagnosis

4. Sarafino Wani RL. 2012. Tuberculosis 1. Epidemiology of TB. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:1539.

of mycobacterium tuberculosis. SSMJ; 5(2): 45-46 16. WHO. Tuberculosis diagnostics: Automated DNA test.

5. Heimbeck J. The infection of tuberculosis. Acta Med http://www.who.int/tb/features_archive/new_rapid_

Scand 1930; 74:143. test/en/ (Accessed on May 07, 2012).

6. van Soolingen D, Hoogenboezem T, de Haas PE, et 17. Helb D, Jones M, Story E, et al. Rapid detection of

al. A novel pathogenic taxon of the Mycobacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampin resistance

tuberculosis complex, Canetti: characterization of an by use of on-demand, near-patient technology. J Clin

exceptional isolate from Africa. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1997; Microbiol 2010; 48:229.

47:1236. 18. Boehme CC, Nabeta P, Hillemann D, et al. Rapid

7. McNeil MR, Brennan PJ. Structure, function and molecular detection of tuberculosis and rifampin

biogenesis of the cell envelope of mycobacteria in resistance. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:1005.

relation to bacterial physiology, pathogenesis and drug 19. Nicol MP, Workman L, Isaacs W, et al. Accuracy of the

resistance; some thoughts and possibilities arising Xpert MTB/RIF test for the diagnosis of pulmonary

from recent structural information. Res Microbiol 1991; tuberculosis in children admitted to hospital in Cape

142:451. Town, South Africa: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis

8. Allen BW, Mitchison DA. Counts of viable tubercle 2011; 11:819.

bacilli in sputum related to smear and culture gradings.

Med Lab Sci 1992; 49:94.

South Sudan Medical Journal 12 Vol 6. No 1. February 2013

Você também pode gostar

- Full Autopsy Released in Death of Kyler PresnellDocumento9 páginasFull Autopsy Released in Death of Kyler PresnellKrystyna May67% (3)

- The Little Book of Sexual HappinessDocumento40 páginasThe Little Book of Sexual Happinesswolf4853100% (2)

- Textbook of Physiotherapy For Obstetric and Gynecological Conditions MASUD PDFDocumento205 páginasTextbook of Physiotherapy For Obstetric and Gynecological Conditions MASUD PDFAlina Gherman-Haiduc75% (4)

- Urological EmergencyDocumento83 páginasUrological EmergencyAlfred LiAinda não há avaliações

- TuberculosisDocumento42 páginasTuberculosisGilbertoMpakaniyeAinda não há avaliações

- Practical Pediatric Hematology PDFDocumento350 páginasPractical Pediatric Hematology PDFHaris Qurashi100% (2)

- Rubella: Dr.T.V.Rao MDDocumento42 páginasRubella: Dr.T.V.Rao MDtummalapalli venkateswara raoAinda não há avaliações

- CPM7th TB in Infancy and ChildhoodDocumento41 páginasCPM7th TB in Infancy and ChildhoodJackyAinda não há avaliações

- Selectividad Abuseofantibiotics - June2001Documento3 páginasSelectividad Abuseofantibiotics - June2001Penny RivasAinda não há avaliações

- The Pathogenic Basis of Malaria: InsightDocumento7 páginasThe Pathogenic Basis of Malaria: InsightRaena SepryanaAinda não há avaliações

- Mycobacterium General Properties: Mycobacteria Cell Wall StructureDocumento12 páginasMycobacterium General Properties: Mycobacteria Cell Wall StructureAhmed ExaminationAinda não há avaliações

- MycobacteriumDocumento14 páginasMycobacteriumSnowie BalansagAinda não há avaliações

- Acid Fast Bacteria: M. Tuberculosis, M. LepraeDocumento22 páginasAcid Fast Bacteria: M. Tuberculosis, M. LepraeelaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter IX MycobacteriaDocumento40 páginasChapter IX Mycobacteriayosef awokeAinda não há avaliações

- Immunity Against MycobacteriaDocumento9 páginasImmunity Against MycobacteriadarmariantoAinda não há avaliações

- Tuberculosis Patogeno AdaptableDocumento15 páginasTuberculosis Patogeno AdaptableMisael VegaAinda não há avaliações

- MycobacteriumDocumento9 páginasMycobacteriumمحمد رائد رزاق إسماعيلAinda não há avaliações

- Fimmu 09 02219Documento13 páginasFimmu 09 02219skgs1970Ainda não há avaliações

- Mjhid 6 1 E2014027Documento11 páginasMjhid 6 1 E2014027Son DellAinda não há avaliações

- Tuberculosis: Mechanism and TherapyDocumento6 páginasTuberculosis: Mechanism and TherapyHyeong Ghil ShinAinda não há avaliações

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis:: 1. Pulmonary Disease 2. Extra-Pulmonary Disseminated DiseaseDocumento3 páginasMycobacterium Tuberculosis:: 1. Pulmonary Disease 2. Extra-Pulmonary Disseminated Diseasesmart_dudeAinda não há avaliações

- Cutaneous Tuberculosis: Epidemiologic, Etiopathogenic and Clinical Aspects - Part IDocumento10 páginasCutaneous Tuberculosis: Epidemiologic, Etiopathogenic and Clinical Aspects - Part IDellAinda não há avaliações

- How Can Immunology Contribute To The Control of Tuberculosis?Documento11 páginasHow Can Immunology Contribute To The Control of Tuberculosis?Parijat BanerjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Tmp2a66 TMPDocumento4 páginasTmp2a66 TMPFrontiersAinda não há avaliações

- 2611 7525 1 SMDocumento12 páginas2611 7525 1 SMAliza Dewi FortuaAinda não há avaliações

- Diaskintest. EnglDocumento3 páginasDiaskintest. Englmusicofmylife101Ainda não há avaliações

- Dwi-Tubercular - Uveitis-ThpIIIDocumento24 páginasDwi-Tubercular - Uveitis-ThpIIIAmelinda SdAinda não há avaliações

- Tuberculosis - Natural History, Microbiology, and Pathogenesis - UpToDateDocumento20 páginasTuberculosis - Natural History, Microbiology, and Pathogenesis - UpToDateandreaAinda não há avaliações

- Immunology of MycobacteriumDocumento37 páginasImmunology of MycobacteriumPhablo vinicius dos santos carneiroAinda não há avaliações

- Benito K. Lim Hong III, M.DDocumento55 páginasBenito K. Lim Hong III, M.DCoy NuñezAinda não há avaliações

- Virulence Factor in Tuberculosis: Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Hsp60 As A KeyDocumento16 páginasVirulence Factor in Tuberculosis: Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Hsp60 As A KeyJOSE VAZQUEZ MORALESAinda não há avaliações

- TB PathologyDocumento13 páginasTB PathologyBaqir BroAinda não há avaliações

- Problem Case Tuberculosis)Documento6 páginasProblem Case Tuberculosis)caltzxAinda não há avaliações

- Prepared By:-Kishor R. LalchetaDocumento56 páginasPrepared By:-Kishor R. Lalchetakishor.lalchetaAinda não há avaliações

- Student Project (Unedit)Documento32 páginasStudent Project (Unedit)vikaAinda não há avaliações

- TuberclosisDocumento3 páginasTuberclosisLaith Al ShdifatAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study Template InfluenzaDocumento5 páginasCase Study Template InfluenzaUjjwal MaharjanAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of Gut and Lung Microbiota in SusceptibilityDocumento20 páginasThe Role of Gut and Lung Microbiota in SusceptibilityannewidiatmoAinda não há avaliações

- Mycobacterium TuberculosisDocumento17 páginasMycobacterium TuberculosisKate Anya Buhat-DiesmaAinda não há avaliações

- Wa0006.Documento12 páginasWa0006.Jose VillasmilAinda não há avaliações

- Genoma TBDocumento14 páginasGenoma TBMARIO CASTROAinda não há avaliações

- Micro Chap 21Documento50 páginasMicro Chap 21Farah ZahidAinda não há avaliações

- Hepatic Tuberculosis (New)Documento23 páginasHepatic Tuberculosis (New)khunleangchhun0% (1)

- Mycobacterium TuberculosisDocumento8 páginasMycobacterium TuberculosisDoru RusuAinda não há avaliações

- My Co BacteriumDocumento5 páginasMy Co BacteriumMukiibi MosesAinda não há avaliações

- Host Defense Mechanisms Against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Qiyao Chai Zhe Lu Cui Hua LiuDocumento20 páginasHost Defense Mechanisms Against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Qiyao Chai Zhe Lu Cui Hua Liurizkarachma64Ainda não há avaliações

- Practical Review of Diagnosis and Management of Cutaneous Tuberculosis in IndonesiaDocumento6 páginasPractical Review of Diagnosis and Management of Cutaneous Tuberculosis in IndonesiaAde Afriza FeraniAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology of Intrathoracic Lymph Node TuberculosisDocumento14 páginasPathophysiology of Intrathoracic Lymph Node TuberculosisNamshaa qureshiAinda não há avaliações

- Description of The MicrobeDocumento3 páginasDescription of The MicrobeMamata GhoshAinda não há avaliações

- 8.TB (Childhood TB)Documento137 páginas8.TB (Childhood TB)auAinda não há avaliações

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis and Tuberculosis - TodarDocumento18 páginasMycobacterium Tuberculosis and Tuberculosis - TodarTanti Dewi WulantikaAinda não há avaliações

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Ecology and Evolution of A Human BacteriumDocumento9 páginasMycobacterium Tuberculosis: Ecology and Evolution of A Human Bacteriumsudipta KhilarAinda não há avaliações

- M.kansasii 2Documento22 páginasM.kansasii 2Ikeh ChisomAinda não há avaliações

- TB PaperDocumento11 páginasTB PapergwapingMDAinda não há avaliações

- Vervloet Et Al-2007-Brazilian Journal of Infectious DiseasesDocumento8 páginasVervloet Et Al-2007-Brazilian Journal of Infectious DiseasesCynthia GalloAinda não há avaliações

- NEJMcibr 0902539Documento3 páginasNEJMcibr 0902539Karen CatariAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S1198743X19300813 MainDocumento5 páginas1 s2.0 S1198743X19300813 MainNia KurniawanAinda não há avaliações

- Cytoquine Storm and SepsisDocumento12 páginasCytoquine Storm and SepsisEduardo ChanonaAinda não há avaliações

- S 46 Mladenka TuberculosisDocumento10 páginasS 46 Mladenka TuberculosisCarlo MaxiaAinda não há avaliações

- Mycobacterium: Dr. NG Woei KeanDocumento28 páginasMycobacterium: Dr. NG Woei KeanWong ShuanAinda não há avaliações

- History: Tuberculosis (TB)Documento24 páginasHistory: Tuberculosis (TB)Rashed ShatnawiAinda não há avaliações

- How Does Mycobacterium Tuberculosis EstablishDocumento3 páginasHow Does Mycobacterium Tuberculosis EstablishamiraAinda não há avaliações

- Review Mycobacterium TuberculosisDocumento9 páginasReview Mycobacterium TuberculosisKoyel Sreyashi BasuAinda não há avaliações

- Patogenesis TBDocumento46 páginasPatogenesis TBJaya Semara PutraAinda não há avaliações

- Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Is An Obligate Intracellular Pathogen That IsDocumento5 páginasMycobacterium Tuberculosis: Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Is An Obligate Intracellular Pathogen That IsArdian Zaka RAAinda não há avaliações

- Early Pregnancy Loss - ACOGDocumento23 páginasEarly Pregnancy Loss - ACOGLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta: William F. WalkenhorstDocumento10 páginasBiochimica Et Biophysica Acta: William F. WalkenhorstLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Identify Plasmodium Lactate/h+ SymportersDocumento8 páginasIdentify Plasmodium Lactate/h+ SymportersLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Ungulate Malaria ParasitesDocumento8 páginasUngulate Malaria ParasitesLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- New Medicine To Improve Medication of MalariaDocumento13 páginasNew Medicine To Improve Medication of MalariaLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Genomic Insight in The Other MalariaDocumento2 páginasGenomic Insight in The Other MalariaLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Fluids and Electrolytes PDFDocumento319 páginasFluids and Electrolytes PDFLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- PediDiabeticKetoacidosisManagementProtocol PDFDocumento34 páginasPediDiabeticKetoacidosisManagementProtocol PDFLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Engwerda2013 PDFDocumento3 páginasEngwerda2013 PDFLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Protective Immunity To Liver-Stage Malaria: ReviewDocumento10 páginasProtective Immunity To Liver-Stage Malaria: ReviewLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- A Newly Discovered Protein Export Machine in Malaria ParasitesDocumento6 páginasA Newly Discovered Protein Export Machine in Malaria ParasitesLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- PediDiabeticKetoacidosisManagementProtocol PDFDocumento34 páginasPediDiabeticKetoacidosisManagementProtocol PDFLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Corticosteeoids in The Treatment of Acute AsthmaDocumento7 páginasCorticosteeoids in The Treatment of Acute AsthmaLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Children With Atopic DermatitisDocumento11 páginasChildren With Atopic DermatitisLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Growth Chart CDC PDFDocumento203 páginasGrowth Chart CDC PDFIrfan FauziAinda não há avaliações

- 00012.pdf Jsessionid PDFDocumento6 páginas00012.pdf Jsessionid PDFLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- EBook Episclera and ScleraDocumento18 páginasEBook Episclera and ScleraLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Children With Atopic DermatitisDocumento11 páginasChildren With Atopic DermatitisLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Practice Guidelines For Obstetric Anesthesia PDFDocumento31 páginasPractice Guidelines For Obstetric Anesthesia PDFLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Children With Atopic DermatitisDocumento11 páginasChildren With Atopic DermatitisLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Unit Kajian Dan Maklumat Drug (Ukmd), Husm. Adr Case ReportDocumento56 páginasUnit Kajian Dan Maklumat Drug (Ukmd), Husm. Adr Case ReportRendry Dwitya WirawanAinda não há avaliações

- Cardiac Rehabilitation in Very Old AdultsDocumento6 páginasCardiac Rehabilitation in Very Old AdultsLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophisiology of ItchDocumento8 páginasPathophisiology of ItchLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- TB Nejm PDFDocumento25 páginasTB Nejm PDFrisanataliasiburianAinda não há avaliações

- 1 FullDocumento12 páginas1 FullMirona ElenaAinda não há avaliações

- Neurological Examination of Motor SystemDocumento7 páginasNeurological Examination of Motor SystemLiviliaMiftaAinda não há avaliações

- Minnesota State High School LeagueDocumento2 páginasMinnesota State High School Leagueapi-301794844Ainda não há avaliações

- Key Points in Obstetrics and Gynecologic Nursing A: Ssessment Formulas !Documento6 páginasKey Points in Obstetrics and Gynecologic Nursing A: Ssessment Formulas !June DumdumayaAinda não há avaliações

- AyurvedicDocumento8 páginasAyurvedicVijay VishwakarmaAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial Dr. SaugiDocumento33 páginasTutorial Dr. SaugifemmytaniaAinda não há avaliações

- Diseases, Ailments, and Disorders in Urinary System - PPTDocumento24 páginasDiseases, Ailments, and Disorders in Urinary System - PPTIsabella Alycia Lomibao100% (1)

- Problem in Complete Denture Treatment and Postinsertion DentureDocumento35 páginasProblem in Complete Denture Treatment and Postinsertion DentureSorabh JainAinda não há avaliações

- 2017ijmrcr PDFDocumento57 páginas2017ijmrcr PDFIvan InkovAinda não há avaliações

- Organ SpeechDocumento11 páginasOrgan SpeechFaa UlfaaAinda não há avaliações

- Vaccines CHNDocumento2 páginasVaccines CHNLyra LorcaAinda não há avaliações

- D 5 LRDocumento2 páginasD 5 LRDianelie BacenaAinda não há avaliações

- Ophtha LectureDocumento634 páginasOphtha LectureIb YasAinda não há avaliações

- Basic Principles of Animal Form and Function: For Campbell Biology, Ninth EditionDocumento66 páginasBasic Principles of Animal Form and Function: For Campbell Biology, Ninth EditionASEEL AHMADAinda não há avaliações

- Primary Amenorrhea Testing AlgorithmDocumento1 páginaPrimary Amenorrhea Testing AlgorithmGabriella AguirreAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomy of The Uvea: Ruth Antolin, MD Doh Eye CenterDocumento75 páginasAnatomy of The Uvea: Ruth Antolin, MD Doh Eye CenterRuth AntolinAinda não há avaliações

- Jaundice Natural RemediesDocumento12 páginasJaundice Natural RemediesprkshshrAinda não há avaliações

- Airway Management 1Documento17 páginasAirway Management 1kamel6Ainda não há avaliações

- Appendectomy Surgery: What Is An Appendix?Documento4 páginasAppendectomy Surgery: What Is An Appendix?Muhammad Ichfan NabiuAinda não há avaliações

- Pathognomonic Signs of Communicable Diseases: JJ8009 Health & NutritionDocumento2 páginasPathognomonic Signs of Communicable Diseases: JJ8009 Health & NutritionMauliza Resky NisaAinda não há avaliações

- Housing of Sheep and GoatsDocumento12 páginasHousing of Sheep and Goatsglennpuputi10Ainda não há avaliações

- Snake BitesDocumento21 páginasSnake BitesarifuadAinda não há avaliações

- Are You Kidding MeDocumento10 páginasAre You Kidding MeChelsea RoseAinda não há avaliações

- 9700 m16 Ms 42 PDFDocumento10 páginas9700 m16 Ms 42 PDFsamihaAinda não há avaliações

- Essay-Vegan Vs OmnivorousDocumento3 páginasEssay-Vegan Vs OmnivorousStiven Diaz Florez100% (1)

- Reproduction SystemDocumento38 páginasReproduction SystemNurfatin AdilaAinda não há avaliações

- Variability and Accuracy of Sahlis Method InEstimation of Haemoglobin ConcentrationDocumento8 páginasVariability and Accuracy of Sahlis Method InEstimation of Haemoglobin Concentrationastrii 08Ainda não há avaliações