Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Vertebrobasiler Disease NEJM

Enviado por

Dex RayDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Vertebrobasiler Disease NEJM

Enviado por

Dex RayDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The new england journal of medicine

review article

current concepts

Vertebrobasilar Disease

Sean I. Savitz, M.D., and Louis R. Caplan, M.D.

From the Department of Neurology, Beth

Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard

Medical School, Boston. Address reprint

requests to Dr. Savitz at the Division of

Cerebrovascular Disease, Department of

Neurology, Palmer 127, Beth Israel Dea-

e ighty percent of strokes are ischemic. twenty percent of is-

chemic events involve tissue supplied by the posterior (vertebrobasilar) circula-

tion (Fig. 1). The paralysis of vertebrobasilar stroke can be devastating, and some

forms have high rates of death.1 Many cases of vertebrobasilar disease remain undiag-

nosed or are incorrectly diagnosed.2 Some common symptoms, such as dizziness or

coness Medical Center, 330 Brookline Ave.,

Boston, MA 02215, or at ssavitz@bidmc. transient loss of consciousness, are misattributed to posterior-circulation ischemia.

harvard.edu. Formerly, clinicians used the catchall term “vertebrobasilar insufficiency” to indicate a

hemodynamic cause of all cases of posterior-circulation ischemia.1,3,4 During the past

N Engl J Med 2005;352:2618-26.

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society.

15 years, information provided by detailed clinical studies and brain imaging has revo-

lutionized our understanding of the clinical aspects, causes, mechanisms, treatments,

and prognosis of posterior-circulation ischemia.1,3

causes and vascular lesions

The most common causes of vertebrobasilar ischemia are embolism, large-artery ath-

erosclerosis, penetrating small-artery disease, and arterial dissection.5-8 Migraine, fibro-

muscular dysplasia, coagulopathies, and drug abuse are much less frequent causes.

Emboli arise from the heart, aorta, and proximal vertebral and basilar arteries.1,3,5 The

distribution of large-artery atherosclerosis differs according to race and sex.9,10 White

men often have atherosclerosis at the origin of the vertebral arteries from the subclavian

arteries. Patients with atherosclerosis at this site often have carotid, coronary, and periph-

eral vascular disease.9-13 Intracranial large-artery atherosclerosis is most common

among blacks, Asians, and women.1,9,10,12

The small arteries that supply the brain stem and thalamus arise from the intracra-

nial vertebral, basilar, and posterior cerebral arteries (Fig. 1). Hypertension increases

the likelihood of lipohyalinotic thickening of these arteries, which, in turn, causes small

infarcts.14 Atherosclerosis of parent arteries can block or extend into the origins of these

penetrating arteries or form microatheromas within these branches, leading to block-

age (intracranial atheromatous branch disease).15,16

Dissections occur in the portions of the extracranial vertebral arteries that are most

freely movable. These are the third portion of the vertebral artery that extends around

the upper cervical vertebrae and the first portion of the vertebral artery between its origin

and its entrance into the intervertebral foramina.1,17,18

symptoms and signs

Dizziness, vertigo, headache, vomiting, double vision, loss of vision, ataxia, numbness,

and weakness involving structures on both sides of the body are frequent symptoms in

patients with vertebrobasilar-artery occlusive disease. The most common signs are limb

weakness, gait and limb ataxia, oculomotor palsies, and oropharyngeal dysfunction.

Posterior-circulation ischemia rarely causes only one symptom but rather produces a

2618 n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23, 2005

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

collection of symptoms and signs depending on

Frontal lobe

which area is ischemic. Fewer than 1 percent of

patients with vertebrobasilar ischemia in the New

England Medical Center Posterior Circulation Reg-

istry (NEMC-PCR) had only a single presenting Temporal

Anterior

lobe

symptom or sign.1,3,5 cerebral

artery

Internal

Middle carotid artery

common patterns cerebral Pituitary

artery Posterior

of presentation communicating

artery

embolism

The most frequent arterial sites of emboli are the Posterior

cerebral artery

intracranial vertebral arteries, which usually lead to

Anterior inferior

cerebellar infarction, and the distal basilar artery, cerebellar artery

Basilar

artery

which leads to infarcts in the upper cerebellum,

midbrain, thalamus, and territories of the posterior Vertebral

artery

cerebral artery — so-called top-of-the-basilar in-

farcts.1,3,5,19-22 Patients with cerebellar infarcts

often report dizziness, occasionally in conjunction

with frank vertigo, blurred vision, difficulty walking, Branches of

Cerebellum

and vomiting. They often veer to one side and can- posterior

cerebral artery

not sit upright or maintain an erect posture with-

Posterior inferior

out support. Patients may have hypotonia of the arm cerebellar artery Anterior Occipital lobe

on the side of the infarct, a sign best elicited by hav- spinal artery

ing them hold their arms straight ahead and then

Figure 1. Arterial Supply of the Brain Stem, Cerebellum, Occipital Lobes,

rapidly lower them, quickly braking the movement. Posterior Temporal Lobes, and Thalamus.

The hypotonic arm overshoots on both descent and The vertebrobasilar arterial supply feeds the brain stem (medulla, pons, and

rapid ascent. Nystagmus is common. Patients with midbrain), cerebellum, occipital lobes, posterior temporal lobes, and thala-

pure cerebellar infarcts do not have hemiparesis or mus (not visible in this view). The arterial supply consists of the extracranial

hemisensory loss. and intracranial vertebral arteries, which unite to form the basilar artery,

Embolic infarcts can involve one posterior cere- which runs midline along the ventral surface of the brain stem, feeding it with

small, deep perforators until it merges with the circle of Willis to give off the

bral artery, which most often leads to a hemianopia posterior cerebral arteries.

of the contralateral visual field,1,3,20,23 as in the pa-

tient described in Figure 2. The patient described

in Figure 2 had occlusion of a vertebral artery caus- by somnolence and sometimes, stupor; inability to

ing transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) related to the make new memories; small, poorly reactive pupils;

lower brain stem and followed by an intraarterial and defective vertical gaze.1,3,21,22

embolus to the right posterior cerebral artery, caus-

ing an occipital-lobe infarct and a left hemianopia. atherosclerotic stenosis and occlusion

Sometimes, hemisensory symptoms are present on Atherostenosis at or near the origin of a vertebral

the same side of the body and face as the hemiano- artery in the neck is often manifested as brief TIAs,

pia. Difficulty reading and naming colors often ac- consisting of dizziness, difficulty focusing visually,

companies large infarcts of the left posterior cere- and loss of balance.13 Attacks occur after a patient

bral artery, whereas neglect of the left visual field has been standing or in situations that reduce blood

and disorientation to place may accompany infarcts pressure or blood flow. These symptoms are relat-

of the right posterior cerebral artery. Bilateral in- ed to ischemia of vestibulocerebellar structures in

farcts of the posterior cerebral arteries cause bilat- the medulla and cerebellum.13 In some patients,

eral visual-field defects and, sometimes, cortical posterior cerebral, cerebellar, or top-of-the-basilar

blindness. Inability to make new memories as well symptoms and signs occur suddenly, owing to em-

as an agitated state can also occur.1,3,21,22 Embolic bolism from the vertebral-artery occlusive lesion.

infarction of the rostral midbrain and thalamus Atherostenosis or occlusion of an intracranial

leads to a top-of-the-basilar syndrome characterized vertebral artery most often causes symptoms and

n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23, 2005 2619

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The new england journal of medicine

Figure 2. Patient with an Embolic Infarct.

A 57-year-old man with hypertension, high cholesterol

A

levels, and angina pectoris awoke one morning and could

not see to his left. During the preceding weeks, he had

had several brief attacks of dizziness accompanied by

difficulty focusing his eyes. During one spell, his body

veered to the right. Examination showed a left homony-

mous hemianopia. A long, high-pitched bruit was heard

in the right supraclavicular region. The angiogram showed

extracranial vertebral-artery occlusion (Panel A). An em-

bolus from the vertebral artery had migrated through the

basilar artery to occlude the right posterior cerebral artery.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed an occipital-lobe

infarct (Panel B).

signs related to ischemia in the lateral medullary

tegmentum, which are referred to as the Wallen-

berg, or lateral medullary, syndrome (Table 1 and

Fig. 3A). Occlusion of an intracranial vertebral ar-

tery can also then become a source of emboli to the

rostral basilar artery and its branches. When both

intracranial vertebral arteries are compromised, the

most frequent clinical pattern is spells of decreased

vision and ataxia, often precipitated by standing or

a reduction in blood pressure. In the NEMC-PCR,

13 of 407 patients had hemodynamically sensitive B

ischemia, most commonly caused by bilateral intra-

cranial vertebral-artery occlusive disease, and they

had multiple brief episodes of dizziness, veering,

perioral paresthesias, and diplopia.5,24

Atherostenosis and occlusion of the basilar ar-

tery usually cause bilateral symptoms and signs or

crossed findings (involving one side of the face and

the contralateral side of the trunk and limbs).1,3,25,26

Motor and oculomotor signs and symptoms pre-

dominate (Table 2) and, when severe, can cause the

locked-in syndrome (Fig. 3B).

penetrating artery disease

Infarcts in the paramedian pons cause pure motor

strokes characterized by weakness of the face, arm,

and leg or arm and leg on one side without visual,

sensory, cognitive, or behavioral abnormalities. At

times, the weak limbs also show a cerebellar type

of incoordination — an ataxic hemiparesis.1,3,14-16

Thalamic lacunes present as pure sensory strokes

with numbness or paresthesias involving the face,

arm, and leg on one side without motor, visual, of the neck or occiput, spreading into the shoul-

cognitive, or behavioral abnormalities.1,3,14,16 der.1,17,18 Diffuse, mostly occipital, headache also

occurs. Dizziness, diplopia, and signs of lateral

arterial dissection medullary or cerebellar infarction can ensue from

The cardinal symptom in patients with vertebral embolism or extension of the dissection to the in-

dissections is pain, most often in the posterior part tracranial vertebral artery. Intracranial vertebral-

2620 n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23 , 2005

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

artery dissections cause medullary, cerebellar, and

Table 1. Signs and Symptoms of Lateral Medullary Infarct.

pontine ischemia and can cause subarachnoid hem-

orrhage.27 General Symptoms Ipsilateral Signs Contralateral Signs

Dizziness, vertigo

symptoms not usually caused by Facial pain Decreased pain and tem- Decreased pain and

posterior-circulation disease perature sensations temperature sensa-

in face tions in trunk, limbs,

or both

Symptoms referable to systemic, circulatory, vestib-

ular, and aural origins are often falsely attributed to Horner’s syndrome

posterior-circulation ischemia. Difficulty sitting without Limb ataxia

support, veering to

one side

isolated attacks of dizziness,

Hoarseness Laryngeal paralysis

light-headedness, or vertigo

Dysphagia Pharyngeal paralysis

“Dizziness” may be used to refer to light-headed-

ness, a lack of mental clarity, or frank vertigo. Verti-

go indicates dysfunction of the peripheral vestibu-

lar or central vestibulocerebellar system. Vertigo in ways causes other accompanying findings, such as

patients with peripheral vestibulopathies is often oculomotor and motor signs.

triggered by sudden movements and positional

changes and is commonly associated with aural drop attacks

symptoms. Vertebral-artery disease can cause tran- A drop attack is defined as a sudden loss of postural

sient attacks of vertigo that are usually accompanied tone and falling without warning. Associated loss

by other brain-stem or cerebellar symptoms. In our of consciousness implicates syncope or seizures as

experience, isolated episodes of vertigo continuing the cause. Drop attacks have inappropriately been

for more than three weeks are almost never caused attributed to transient ischemia of the posterior

by vertebrobasilar disease. Rarely, and almost ex- circulation. Brain-stem ischemia can affect cortico-

clusively in patients with diabetes, occlusion of the spinal tracts subserving motor control of the limbs,

branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery of but when it does so, it usually causes persistent

the basilar artery supplying the inner ear can cause weakness. Not a single patient in the NEMC-PCR

vertigo, unilateral hearing loss, or both before caus- had a drop attack as the only symptom.1,3,5 In the

ing brain-stem infarction.28 absence of symptoms or findings that suggest

Light-headedness usually reflects presyncope brain-stem or cerebellar dysfunction, posterior-

related to circulatory, systemic, or cardiac disease. circulation ischemia is rarely the cause of drop

In the absence of neurologic symptoms or signs, attacks.

light-headedness is rarely a manifestation of verte-

brobasilar ischemia. The diagnostic yield of neuro-

vascular testing (neuroimaging and ultrasonogra- evaluation of patients

with suspected posterior-

phy) in patients with isolated syncope is very low.29 circulation ischemia

Isolated syncope poses no increased risk of stroke.30

Only 7 percent of the 407 patients in our series de- Thorough evaluation of a patient’s history and

scribed light-headedness, and none presented with findings on physical and neurologic examinations

light-headedness as an isolated symptom.1,3,5 should provide guidance regarding which inves-

tigations to perform. All patients in whom verte-

transient decrease in consciousness brobasilar-territory strokes or TIAs are suspected

Seizures and syncope are much more common should undergo neuroimaging, preferably magnet-

causes of temporary loss of consciousness than is ic resonance imaging (MRI), because computed to-

cerebrovascular disease. The reticular activating sys- mography (CT) provides less complete visualization

tem, which promotes wakefulness, is located in the of the brain stem, owing to artifacts related to the

paramedian tegmentum of the upper brain stem. skull. MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging is the

Basilar-artery occlusions can interrupt the function most sensitive test available to detect acute infarcts.

of these fibers and impair consciousness. Coma Most patients with posterior-circulation strokes and

may occur. However, basilar occlusive disease al- some patients with TIAs related to the posterior-

n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23, 2005 2621

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The new england journal of medicine

Patients with pacemakers or other circumstanc-

A Solitary-tract es that do not permit the use of MRI should under-

nucleus Hypoglossal go CT and CT angiography unless such approaches

Medial nucleus

vestibular nucleus Dorsal are contraindicated. High-quality CT angiography

vagal Medial longitudinal can be used to delineate the extracranial and intra-

Inferior vestibular nucleus fasciculus

nucleus cranial posterior circulation and is very helpful for

Trigeminal-nerve

Restiform tract

evaluating patients with suspected basilar-artery oc-

body

Trigeminal-nerve clusion.36 Duplex ultrasonography can also be used

Spinothalamic nucleus to show the proximal vertebral arteries,37 and Dop-

tract

pler studies of the vertebral arteries in the neck can

Sympathetic

Nucleus

tract

reveal whether blood flow is antegrade or reversed.

ambiguus

Transcranial Doppler studies can be used to show

occlusive lesions in the intracranial vertebral and

Inferior proximal basilar arteries. Ultrasonography of the

olivary nucleus

Pyramidal tract carotid arteries is seldom useful in the evaluation

Medial lemniscus

of patients with posterior-circulation ischemia. In

rare cases of embolism, the posterior cerebral artery

B arises anomalously directly from the intracranial

carotid artery.

Cardiac investigations including electrocardiog-

raphy, echocardiography, and rhythm monitoring

are important parts of the evaluation to search for

cardiac and aortic sources of the embolism, espe-

cially in patients with no cervicocranial occlusive

lesions that explain the symptoms and signs and in

patients with multiple brain infarcts in different

vascular territories.

Screening blood and coagulation tests should

include a complete blood count and coagulation

studies. Other tests for genetic and acquired coag-

Figure 3. Two Types of Vertebrobasilar Infarcts. ulopathies and measurement of antiphospholipid

Panel A shows the portions of the brain affected by the Wallenberg syndrome, antibodies may be appropriate in patients who have

which is an infarction of the lateral portion of the medullary tegmentum. The a history suggesting prior venous or arterial occlu-

most common cause is occlusion of the intracranial vertebral artery. Symp- sions or in those in whom no cardiac, aortic, or cer-

toms and signs are described in Table 1. Panel B shows the histopathological vicocranial lesions are found.

findings at autopsy in a patient who had extensive bilateral infarction of the

Accurate diagnosis of the specific type of stroke

pons as a result of a basilar-artery embolism (Luxol fast blue). The extracranial

vertebral artery was dissected in a skiing accident, and a thrombus subse- and vascular and brain lesions requires the follow-

quently developed, which migrated to the basilar artery, causing severe limb ing: a demographic assessment (age, race, and sex)

and facial paralysis and leaving the patient able only to move her eyes up and and an evaluation of risk factors for stroke; knowl-

down in order to communicate (referred to as the locked-in syndrome). edge of the course of symptoms (for example,

whether the stroke was preceded by a single or

multiple varied or stereotypical TIAs, whether the

circulation territory that last more than an hour onset was sudden and not preceded by TIAs, and

show acute lesions on diffusion-weighted imag- whether the ischemia is progressive); matching of

ing.31-33 Rarely, diffusion-weighted imaging may the patient’s symptoms and signs to known pattern

be normal in patients with an acute vertebrobasilar of ischemia; and brain and vascular imaging.

stroke, but such a result does not exclude infarction.

Follow-up studies often reveal infarcts matching the prognosis

clinical presentation.34 Magnetic resonance angi-

ography can be used to identify the location and se- The outcome of vertebrobasilar stroke depends on

verity of occlusions in the large arteries of the neck the severity of the neurologic signs, the presence or

and intracranial lesions.31,35 absence of arterial lesions, the location and extent

2622 n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23 , 2005

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

stroke when administered within three hours af-

Table 2. Signs and Symptoms of Basilar-Artery Occlusion.

ter the onset of stroke, after brain hemorrhage has

Corticospinal been excluded on the basis of CT.40 Three studies

Limb weakness (often bilateral) of the intravenous administration of thrombolytic

Limb hyperreflexia

Extensor plantar response agents for vertebrobasilar disease reported mixed

Corticobulbar results.41-43 Following the NINDS guidelines,

Facial weakness Grond et al. treated 12 patients with t-PA within

Dysarthria

Dysphagia

three hours after the onset of stroke. Ten of the 12

Increased gag reflex patients had favorable outcomes, 1 had a poor out-

Oculomotor come, and 1 died.41 In another study of five pa-

Diplopia tients who received t-PA within six hours after the

Gaze palsies

Nystagmus onset of symptoms,42 two patients had minor par-

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia tial reperfusion and one had complete reperfu-

Reticular activating system sion. Three of the patients died, and one remained

Reduced consciousness “locked-in.” Montavont et al. treated 18 patients

within seven hours after the onset of stroke.43 Three

months after treatment, 10 of the 18 patients were

of infarction, and the mechanism of ischemia.1,38 independent (i.e., they were able to look after them-

The rate of death immediately after posterior-circu- selves with no or only slight disability), but 2 had

lation stroke is approximately 3 to 4 percent.38,39 died and the condition of 6 was poor.43

In the NEMC-PCR, 3.6 percent of patients died, Thrombolytic agents are also administered intra-

and 18 percent of patients had a major disability.38 arterially through a catheter directed to the throm-

Cardiac embolism, basilar-artery involvement, and bus. In a retrospective study of 65 patients with

the involvement of multiple intracranial territories vertebrobasilar occlusions, the 43 patients given

increase the risk of a poor outcome irrespective of urokinase or streptokinase — two thirds of whom

the patient’s age and underlying risk factors.38 were treated within 24 hours after the onset of

Basilar-artery occlusive disease carries a high risk stroke — had better survival rates and more favor-

of disability and death, and efforts should be di- able outcomes than the 22 patients who were treat-

rected at identifying this lesion as quickly as possi- ed with antithrombotic agents. Among the patients

ble.1,26,38 who were given thrombolytic agents, only those in

whom the occlusive artery recanalized survived.44

In nine additional reports, among 285 patients who

immediate and

preventive therapy were mostly given t-PA more than eight hours after

the onset of stroke,45 62 percent had good recanal-

Various medical, interventional, and surgical ap- ization and 28 percent of the overall population sub-

proaches are available to treat ischemia of the pos- sequently did well. Brandt et al. found that among

terior circulation of the brain, but none have been 51 patients who underwent thrombolysis for acute

thoroughly tested in randomized trials. The poten- vertebrobasilar lesions, those with embolic occlu-

tial treatments are the same as those used for ische- sions that were short and involved the proximal

mia of the anterior circulation of the brain. Howev- basilar artery with good collateral arteries were most

er, few trials have classified patients with ischemic likely to have recanalization and a good outcome.

stroke according to whether they have anterior- Patients who were comatose or tetraplegic or who

circulation or posterior-circulation disease. Among had chronic white-matter abnormalities had poor

the trials that have done so, only a handful have outcomes.46

evaluated and reported the cardiac, arterial, and Clinicians have insufficient data to guide the

hematologic causes of the strokes. choice between intravenous and intraarterial throm-

bolytic therapy for vertebrobasilar ischemia. If pa-

short-term medical management tients present within three hours after the onset of

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders symptoms, some neurologists follow NINDS guide-

and Stroke (NINDS) trial showed that intravenous lines and administer t-PA intravenously after CT has

administration of tissue plasminogen activator excluded hemorrhage. We favor brain and vascular

(t-PA) enhances neurologic recovery from ischemic imaging (CT with CT angiography or diffusion-

n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23, 2005 2623

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

The new england journal of medicine

weighted MRI with magnetic resonance angiogra- circulation disease.51 In the European Stroke Pre-

phy) before deciding whether to use thrombolysis, vention Study, among patients with clinically doc-

especially if more than three hours has passed since umented vertebrobasilar-territory TIAs or strokes,

the onset of symptoms or the diagnosis is uncertain. strokes occurred in 5.7 percent of 255 patients treat-

If a vertebral-artery occlusion is found, we give in- ed with the combination of aspirin and modified-

travenous t-PA. When imaging studies suggest release dipyridamole, as compared with 10.8 per-

basilar-artery occlusion, we recommend cerebral cent of patients who received placebo (P=0.005).52

angiography and intraarterial thrombolysis, be- We treat patients with large-artery stenosis and

cause basilar-artery occlusions carry an increased small-artery disease with antiplatelet agents. For

risk of death and disability and there is extensive patients with severe, large-artery, flow-limiting ste-

experience with intraarterial thrombolysis, even if it nosis and vertebral-artery dissection,18 we consider

is given 12 to 24 hours after the onset of stroke in treatment with anticoagulants in order to prevent

this condition.44,45 distal embolization and progression of infarcts.

Some patients with intracranial vertebrobasilar When imaging shows atherosclerotic plaques, we

occlusive disease are very sensitive to changes in also prescribe statins unless the patient has a low-

brain perfusion from decreases in blood pressure density lipoprotein cholesterol level of less than

or blood volume, and even from sitting up or stand- 70 mg per deciliter (1.8 mmol per liter).53 Patients

ing.24,47 In these patients, maximizing blood flow with large-artery atherostenosis who continue to

and blood volume by using fluids and pressors is have ischemic events while receiving medical thera-

important. py are referred for surgery, angioplasty, or stenting,

depending on the nature and location of the arterial

prevention lesions (see below). Randomized trials should be

Strong evidence from randomized, controlled trials designed to address which therapeutic options are

provides support for the efficacy of anticoagulation most appropriate for specific stroke mechanisms

with warfarin to prevent subsequent cerebrovascu- and arterial occlusive lesions.

lar events in patients with embolic stroke of cardiac

origin. In a retrospective comparison of the effec- future directions

tiveness of warfarin and aspirin among 68 patients

with symptomatic intracranial-artery stenosis that endovascular procedures

was arteriographically documented, warfarin was Evidence provided by scattered case series suggests

superior in patients with vertebrobasilar occlusive that vertebrobasilar angioplasty and stenting may

disease.48 However, a prospective, double-blind become important therapeutic strategies for large-

study involving patients with symptomatic intra- artery vertebrobasilar disease. Preliminary results of

cranial stenosis of 50 to 99 percent, which was pre- angioplasty or stenting of occlusive vertebral-artery

maturely terminated after the randomization of 569 lesions in the neck show that restenosis is more

patients to warfarin or aspirin (1300 mg), showed common than with carotid-artery stenting.54 The

that both agents were equally effective but that war- small diameter and angulation of the vertebral-

farin caused significantly more serious hemorrhag- artery origin complicate endovascular treatment.

es.49 The Warfarin–Aspirin Recurrent Stroke Study Intracranial vertebral- and basilar-artery angioplas-

of secondary prevention also showed that aspirin ty and stenting have produced mixed results, with a

and warfarin were equally efficacious in patients relatively high rate of complications.55 Although

with noncardioembolic stroke.50 the results are preliminary, mechanical removal of

The results of prospective trials showed that anti- thromboemboli may become potentially useful in

platelet agents (aspirin, ticlopidine, clopidogrel, di- patients who cannot receive thrombolytic drugs

pyridamole, and the combination of aspirin and and as an adjunct to thrombolysis.56 We await large,

dipyridamole) were beneficial in series of patients controlled trials comparing endovascular revas-

with TIAs and strokes. However, only two studies cularization with various medical therapies.

analyzed the findings in relationship to arterial ter-

ritories, and none reported the nature of the vascu- surgery

lar occlusive lesions. Ticlopidine was superior to Endarterectomy for severe extracranial vertebral-

aspirin for secondary cerebrovascular protection, artery disease has low rates of complications and

especially in patients with symptomatic posterior- mortality when performed by surgeons with ex-

2624 n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23 , 2005

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

tensive experience.57 The indications for vertebral- success, but no trials were undertaken to prove

artery surgery are still uncertain. Before the advent their effectiveness.1

of intracranial angioplasty, bypass shunts were Supported by a grant (0475008N) from the American Heart Asso-

surgically created between extracranial arteries and ciation (to Dr. Savitz).

Dr. Caplan reports having served on advisory boards of Glaxo-

the intracranial posterior circulation, with some SmithKline, Wyeth, Boehringer Ingelheim, and AstraZeneca.

references

1. Caplan LR. Posterior circulation disease: 17. Mokri B, Houser OW, Sandok BA, Piep- Diffusion MRI in patients with transient is-

clinical findings, diagnosis, and manage- gras DG. Spontaneous dissections of the chemic attacks. Stroke 1999;30:1174-80.

ment. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell Science, vertebral arteries. Neurology 1988;38:880- 33. Marx JJ, Mika-Gruettner A, Thoemke F,

1996. 5. et al. Diffusion weighted magnetic reso-

2. Ferro JM, Pinto AN, Falcao I, et al. Diag- 18. Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection nance imaging in the diagnosis of reversible

nosis of stroke by the nonneurologist: a val- of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J ischaemic deficits of the brainstem. J Neurol

idation study. Stroke 1998;29:1106-9. Med 2001;344:898-906. Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;72:572-5.

3. Caplan LR. Posterior circulation ische- 19. Caplan LR, Amarenco P, Rosengart A, et 34. Oppenheim C, Stanescu R, Dormont D,

mia: then, now, and tomorrow — the Thom- al. Embolism from vertebral artery origin oc- et al. False-negative diffusion-weighted MR

as Willis Lecture-2000. Stroke 2000;31:2011- clusive disease. Neurology 1992;42:1505-12. findings in acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am

23. 20. Yamamoto Y, Georgiadis AI, Chang J Neuroradiol 2000;21:1434-40.

4. Millikan CH, Siekert RG. Studies in H-M, Caplan LR. Posterior cerebral artery 35. Wentz KU, Rother J, Schwartz A, Mattle

cerebrovascular disease: the syndrome of territory infarcts in the New England Medi- HP, Suchalla R, Edelman RR. Intracranial

intermittent insufficiency of the basilar arte- cal Center Posterior Circulation Registry. vertebrobasilar system: MR angiography.

rial system. Mayo Clin Proc 1955;30:61-8. Arch Neurol 1999;56:824-32. Radiology 1994;190:105-10.

5. Caplan LR, Wityk RJ, Glass TA, et al. New 21. Caplan LR. “Top of the basilar” syn- 36. Brandt T, Knauth M, Wildermuth S, et

England Medical Center Posterior Circula- drome: selected clinical aspects. Neurology al. CT angiography and Doppler sonogra-

tion Registry. Ann Neurol 2004;56:389-98. 1980;30:72-9. phy for emergency assessment in acute basi-

6. Bogousslavsky J, Van Melle G, Regli F. 22. Mehler MF. The rostral basilar artery lar artery ischemia. Stroke 1999;30:606-12.

The Lausanne Stroke Registry: analysis of syndrome: diagnosis, etiology, prognosis. 37. Ackerstaff RGA. Duplex scanning of

1,000 consecutive patients with first stroke. Neurology 1989;39:9-16. the aortic arch and vertebral arteries. In:

Stroke 1988;19:1083-92. 23. Pessin MS, Lathi ES, Cohen MB, Kwan Bernstein EF, ed. Vascular diagnosis. 4th ed.

7. Moulin T, Tatu L, Vuillier F, Berger E, ES, Hedges TR III, Caplan LR. Clinical fea- St. Louis: Mosby, 1993:315-21.

Chavot D, Rumbach L. Role of a stroke data tures and mechanism of occipital infarction. 38. Glass TA, Hennessey PM, Pazdera L, et

bank in evaluating cerebral infarction sub- Ann Neurol 1987;21:290-9. al. Outcome at 30 days in the New England

types: patterns and outcome of 1,776 con- 24. Shin H-K, Yoo K-M, Chang H-M, Caplan Medical Center Posterior Circulation Regis-

secutive patients from the Besancon Stroke LR. Bilateral intracranial vertebral artery dis- try. Arch Neurol 2002;59:369-76.

Registry. Cerebrovasc Dis 2000;10:261-71. ease in the New England Medical Center 39. Bogousslavsky J, Regli F, Maeder P,

8. Vemmos K, Takis C, Georgilis K, et al. Posterior Circulation Registry. Arch Neurol Meuli R, Nader J. The etiology of posterior

The Athens Stroke Registry: results of a five- 1999;56:1353-8. circulation infarcts: a prospective study us-

year hospital-based study. Cerebrovasc Dis 25. Kubik CS, Adams RD. Occlusion of the ing magnetic resonance imaging and mag-

2000;10:133-41. basilar artery: a clinical and pathologic study. netic resonance angiography. Neurology

9. Caplan LR, Gorelick PB, Hier DB. Race, Brain 1946;69:73-121. 1993;43:1528-33.

sex, and occlusive cerebrovascular disease: 26. Voetsch B, Dewitt LD, Pessin MS, Caplan 40. The National Institute of Neurological

a review. Stroke 1986;17:648-55. LR. Basilar artery occlusive disease in the Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Study Group. Tis-

10. Gorelick PB, Caplan LR, Hier DB, et al. New England Medical Center Posterior Cir- sue plasminogen activator for acute ische-

Racial differences in the distribution of pos- culation Registry. Arch Neurol 2004;61:496- mic stroke. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1581-7.

terior circulation occlusive disease. Stroke 504. 41. Grond M, Rudolf J, Schmulling S, Sten-

1985;16:785-90. 27. Caplan LR, Baquis GD, Pessin MS, et al. zel C, Neveling M, Heiss WD. Early intrave-

11. Hutchinson EC, Yates PO. Carotico- Dissection of the intracranial vertebral ar- nous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue-

vertebral stenosis. Lancet 1957;272:2-8. tery. Neurology 1988;38:868-77. type plasminogen activator in vertebrobasilar

12. Feldmann E, Daneault N, Kwan E, et al. 28. Lee H, Cho Y-W. Auditory disturbance as ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol 1998;55:466-9.

Chinese-white differences in the distribution a prodrome of anterior inferior cerebellar 42. von Kummer R, Forsting M, Sartor K,

of occlusive cerebrovascular disease. Neurol- artery infarction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psy- Hacke W. Intravenous recombinant tissue

ogy 1990;40:1541-5. chiatry 2003;74:1644-8. plasminogen activator in acute stroke. In:

13. Wityk RJ, Chang H-M, Rosengart A, et 29. Linzer M, Yang EH, Estes NA III, Wang Hacke W, Del Zoppo GJ, Hirschberg M, eds.

al. Proximal extracranial vertebral artery dis- P, Vorperian VR, Kapoor WN. Diagnosing Thrombolytic therapy in acute ischemic

ease in the New England Medical Center syncope. Part 1: value of history, physical stroke. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1991:

Posterior Circulation Registry. Arch Neurol examination, and electrocardiography. Ann 161-7.

1998;55:470-8. Intern Med 1997;126:989-96. 43. Montavont A, Nighoghossian N, Derex

14. Fisher CM. The arterial lesions underly- 30. Savage DD, Corwin L, McGee DL, Kan- L, et al. Intravenous r-tPA in vertebrobasilar

ing lacunes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1968; nel WB, Wolf PA. Epidemiologic features of acute infarcts. Neurology 2004;62:1854-6.

12:1-15. isolated syncope: the Framingham Study. 44. Hacke W, Zeumer H, Ferbert A, Bruck-

15. Fisher CM, Caplan LR. Basilar artery Stroke 1985;16:626-9. mann H, del Zoppo GJ. Intra-arterial throm-

branch occlusion: a cause of pontine infarc- 31. Linfante I, Llinas RH, Schlaug G, Chaves bolytic therapy improves outcome in pa-

tion. Neurology 1971;21:900-5. C, Warach S, Caplan LR. Diffusion-weight- tients with acute vertebrobasilar occlusive

16. Caplan LR. Intracranial branch athero- ed imaging and National Institutes of Health disease. Stroke 1988;19:1216-22.

matous disease: a neglected, understudied, Stroke Scale in the acute phase of posterior- 45. Caplan LR. Thrombolysis in vertebro-

and underused concept. Neurology 1989; circulation stroke. Arch Neurol 2001;58: basilar occlusive disease. In: Lyden P, ed.

39:1246-50. [Erratum, Neurology 1990;40: 621-8. Thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke. 2nd

725.] 32. Kidwell CS, Alger JR, Di Salle F, et al. ed. Totowa, N.J.: Humana Press, 2005:203-9.

n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23, 2005 2625

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

current concepts

46. Brandt T, von Kummer R, Muller-Kup- A comparison of warfarin and aspirin for Lesions in the Vertebral or Intracranial Ar-

pers M, Hacke W. Thrombolytic therapy of the prevention of recurrent ischemic stroke. teries (SSYLVIA): study results. Stroke 2003;

acute basilar artery occlusion: variables af- N Engl J Med 2001;345:1444-51. 34:253. abstract.

fecting recanalization and outcome. Stroke 51. Grotta JC, Norris JW, Kamm B. Preven- 55. Gupta R, Schumacher HC, Mangla S, et

1996;27:875-81. tion of stroke with ticlopidine: who benefits al. Urgent endovascular revascularization

47. Caplan LR, Sergay S. Positional cerebral most? Neurology 1992;42:111-5. for symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic

ischemia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 52. Sivenius J, Riekkinen PJ, Smets P, Laak- stenosis. Neurology 2003;61:1729-35.

1976;39:385-91. so M, Lowenthal A. The European Stroke 56. Gobin YP, Starkman S, Duckwiler GR, et

48. Chimowitz MI, Kokkinos J, Strong J, et Prevention Study (ESPS): results by arterial al. MERCI I: a phase I study of mechanical

al. The Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intra- distribution. Ann Neurol 1991;29:596-600. embolus removal in cerebral ischemia.

cranial Disease Study. Neurology 1995;45: 53. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, et al. Stroke 2004;35:2848-54.

1488-93. Implications of recent clinical trials for the 57. Berguer R, Flynn LM, Kline RA, Caplan

49. Chimowitz MI, Lynn M-J, Howlett- National Cholesterol Education Program L. Surgical reconstruction of the extracrani-

Smith H, et al. Comparison of warfarin and Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circu- al vertebral artery: management and out-

aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial lation 2004;110:227-39. come. J Vasc Surg 2000;31:9-18.

stenosis. N Engl J Med 2005;352:1305-16. 54. Lutsep HL, Barnwell SL, Mawad M, et al. Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society.

50. Mohr JP, Thompson JL, Lazar RM, et al. Stenting of Symptomatic Atherosclerotic

2626 n engl j med 352;25 www.nejm.org june 23, 2005

Downloaded from www.nejm.org at VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY on September 21, 2005 .

Copyright © 2005 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Comprehensive Guide to Migraine: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentDocumento29 páginasComprehensive Guide to Migraine: Causes, Symptoms and TreatmentNatalie MbonjaniAinda não há avaliações

- 0199605602Documento318 páginas0199605602Eudon MuliawanAinda não há avaliações

- Neurology Clerkship Study GuideDocumento84 páginasNeurology Clerkship Study GuideHilary Steele100% (1)

- Yyyyy Y YDocumento49 páginasYyyyy Y YSiva Nantham100% (1)

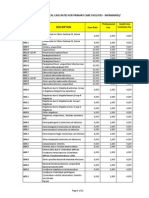

- PhilHealth Circular No. 0035, s.2013 Annex 5 List of Medical Case Rates For Primary Care FacilitiesDocumento22 páginasPhilHealth Circular No. 0035, s.2013 Annex 5 List of Medical Case Rates For Primary Care FacilitiesChrysanthus HerreraAinda não há avaliações

- Ménière's Disease: Vertigo - Hearing Loss - Tinnitus: A Psychosomatically Oriented Presentation Helmut SchaafDocumento304 páginasMénière's Disease: Vertigo - Hearing Loss - Tinnitus: A Psychosomatically Oriented Presentation Helmut SchaafG PalaAinda não há avaliações

- Final Written ENT With CoverDocumento231 páginasFinal Written ENT With CoverAlyAl-MakhzangyAinda não há avaliações

- Ent MCQ 20000 PDFDocumento19 páginasEnt MCQ 20000 PDFIvana Supit60% (5)

- GI AND ENO QUESTIONERDocumento26 páginasGI AND ENO QUESTIONERRymmus Asuncion100% (1)

- Managing ENT DisordersDocumento26 páginasManaging ENT DisordersShreyas Walvekar100% (3)

- Edoskopi FleksibelDocumento4 páginasEdoskopi FleksibelDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- Disfagia Pasca RadioterapiDocumento8 páginasDisfagia Pasca RadioterapiDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- Brain Abscess Management: Presenter: Pankaj Ailawadhi Moderators: PROF. BS SHARMA Dr. Sumit SinhaDocumento86 páginasBrain Abscess Management: Presenter: Pankaj Ailawadhi Moderators: PROF. BS SHARMA Dr. Sumit SinhaDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- Sensory Examination DefinitionsDocumento13 páginasSensory Examination DefinitionsDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- Guideline Prevention Venous ThromboembolismDocumento157 páginasGuideline Prevention Venous ThromboembolismDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- The Management of DVT - The Autar PDFDocumento11 páginasThe Management of DVT - The Autar PDFFayza Rihastara100% (1)

- Deep-Vein Thrombosis PDFDocumento25 páginasDeep-Vein Thrombosis PDFDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- Deep Vein ThrombisisDocumento13 páginasDeep Vein ThrombisisDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- Dengue Guideline DengueDocumento33 páginasDengue Guideline DenguedrkkdbAinda não há avaliações

- Gagal GinjalDocumento34 páginasGagal GinjalDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines On Clinical Management DFDHF2009Documento44 páginasGuidelines On Clinical Management DFDHF2009Desti PasmawatiAinda não há avaliações

- Denguide LabDocumento10 páginasDenguide LabHeide Danica A. BaltazarAinda não há avaliações

- Vocab U LarryDocumento3 páginasVocab U LarryDex RayAinda não há avaliações

- Subjective Visual Vertical in Vestibular Disorders Measured With The Bucket TestDocumento9 páginasSubjective Visual Vertical in Vestibular Disorders Measured With The Bucket Testcamila hernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Advances in Vestibular Rehabilitation: Shaleen Sulway Susan L. WhitneyDocumento6 páginasAdvances in Vestibular Rehabilitation: Shaleen Sulway Susan L. WhitneymykedindealAinda não há avaliações

- Approach To AtaxiaDocumento6 páginasApproach To AtaxiaVivek KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Vertigo and ImbalanceDocumento19 páginasVertigo and ImbalanceDiena HarisahAinda não há avaliações

- Motion Sickness Its Pathophysiology and TreatmentDocumento7 páginasMotion Sickness Its Pathophysiology and TreatmentimmanueldioAinda não há avaliações

- Main ICM Shelf Exam (2012 Nov MUA)Documento8 páginasMain ICM Shelf Exam (2012 Nov MUA)mentawistAinda não há avaliações

- DizzinessDocumento6 páginasDizzinessRebecca WongAinda não há avaliações

- Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)Documento91 páginasBenign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV)UjjawalShriwastavAinda não há avaliações

- NeuroMisc NotesDocumento17 páginasNeuroMisc Notessmian08Ainda não há avaliações

- Dizziness and Balance ProblemsDocumento20 páginasDizziness and Balance ProblemsSeldon GoAinda não há avaliações

- NeurologiaDocumento216 páginasNeurologiaPietro BracagliaAinda não há avaliações

- Vertigo BPPV Benign VertigoDocumento6 páginasVertigo BPPV Benign Vertigoaokan@hotmail.comAinda não há avaliações

- Central VertigoDocumento9 páginasCentral VertigoDiayanti TentiAinda não há avaliações

- Overview of The Anatomy and Physiology: AuditionDocumento16 páginasOverview of The Anatomy and Physiology: AuditionEm Hernandez AranaAinda não há avaliações

- Una CoalesDocumento394 páginasUna Coalesabuzeid5100% (1)

- ENT CourseDocumento29 páginasENT Coursetaliya. shvetzAinda não há avaliações

- #Complications of Suppurative Otitis MediaDocumento8 páginas#Complications of Suppurative Otitis MediaameerabestAinda não há avaliações

- ENT Vertigo FINAL v0.41Documento1 páginaENT Vertigo FINAL v0.41Farmasi BhamadaAinda não há avaliações

- Dr. Chitale ENT Hospital - Vertigo Center in PuneDocumento5 páginasDr. Chitale ENT Hospital - Vertigo Center in PuneDr. Vinaya ChitaleAinda não há avaliações

- Scott III OtologyDocumento604 páginasScott III OtologyDr-Firas Nayf Al-ThawabiaAinda não há avaliações