Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Ethiopia's Health Extension

Enviado por

Mulugeta AbebawTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Ethiopia's Health Extension

Enviado por

Mulugeta AbebawDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Perspective

Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program:

Improving Health through Community Involvement

Hailom Banteyerga PhD

This paper is based primarily on three major studies conducted at

Miz-Hasab Research Center (MHRC): The Last Ten Kilometers—

ABSTRACT L10K (2008);[7] System Wide Effect of the Fund (SWEF, 2010),[8]

The Health Extension Program is one of the most innovative

community-based health programs in Ethiopia. It is based on the and Good Health at Low Cost (GHLC).[9] These found that HEP

assumption that access to and quality of primary health care in accelerated access to primary health care and had an impact in

rural communities can be improved through transfer of health reducing communicable diseases and maternal and childhood

knowledge and skills to households. Since it became operational in mortality. We share this experience for the benefit of other coun-

2004–2005, the Program has had a tangible effect on the thinking tries in the same economic stratum.

and practices of rural people regarding disease prevention, family

health, hygiene and environmental sanitation. It has enabled

What is the Health Extension Program (HEP)? HEP is a com-

Ethiopia to increase primary health care coverage from 76.9% in

2005 to 90% in 2010.

munity-based health service delivery program whose educational

approach is based on the diffusion model, which holds that com-

KEYWORDS Family health, health education, health program, munity behavior is changed step by step: training early adopters

disease prevention, health policy, health priorities, environmental first, then moving to the next group that is ready to change. Those

hygiene, sanitation, Millennium Development Goals, Ethiopia resistant to change would gradually be conditioned to change be-

cause of changes in their environment.[10] HEP assumes that

health behavior can be enhanced in communities by creating

model families that others will admire and emulate.[5,10]

INTRODUCTION

Ethiopia is one of the poorest countries in the world with a US$330 HEP has four health subprograms: disease prevention, family

per capita Gross National Income in 2009. The health system re- health, environmental hygiene and sanitation, and health educa-

mained weak until the country introduced a 20-year health sec- tion and communication;[5] these correspond to the elements of

tor development program in 1977, which is being implemented in primary health care coverage as defined in the Alma Ata Declara-

four phases.[1] The civil war waged during the 17 years of military tion.[11] Every village with 5000 residents builds a health post.

rule from 1974 to 1991 destroyed the health delivery system, and Two female HEWs who have completed tenth grade are recruited

the country faced serious economic problems leading to short- from the same community and trained in HEP modules for one

ages of skilled health human resources, pharmaceuticals, and year, after which they return home as salaried frontline health

health service delivery facilities. care staff. According to the FMOH:

These conditions, coupled with harmful traditional practices HEWs are the first point of contact of the community with the

such as female genital mutilation, meant that Ethiopia continued health system, delivering integrated preventive, promotive and

to suffer from a high disease burden, of which 60% was pre- curative health services, with a special focus on maternal and

ventable.[2] Maternal and childhood mortality are still among the child health. The aim is to ensure continuity of care throughout

highest in Africa: under-five mortality was 210 per 1000 children the lifecycle (adolescence, pregnancy, childbirth, postnatal pe-

in 1990, falling to 104 per 1000 in 2009.[3] Maternal mortality riod, and adulthood) and also between places of care giving

was 673 per 100,000 live births in 2005, dropping to 470 per services, and clinical-care settings—having wide implications

100,000 in 2008.[4] Most of the causes of child and maternal for the achievement of MDGs in Ethiopia.[12]

mortality are preventable. Lack of information and knowledge

on prevention, shortage of health facilities within accessible dis- HEWs’ major task is increasing knowledge and skills of commu-

tance, and insufficient skilled health personnel to deliver ser- nities and households to deal with preventable diseases and be

vices have been contributing factors to high rates. Malaria, HIV/ able to access services available at clinics and hospitals. Since

AIDS, TB, waterborne diseases, and respiratory infections re- HEP considers maternal and child health tracer indicators of good

main among the top ten killer diseases.[2] health, HEWs give special attention to family health. In addition

to conducting preventive family health education and sanitation,

The Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) of Ethiopia launched the they can supervise intake of community Directly Observable

Health Extension Program (HEP) in 2003 and it became opera- Treatment-Short Course (DOTS) for TB and antiretroviral treat-

tional with the 2004–2005 graduation of 7136 Health Extension ment for HIV/AIDS; conduct rapid diagnostic tests for malaria

Workers (HEW), trained to work mainly in disease prevention and administer malaria drugs; attend uncomplicated childbirth;

and health promotion in rural villages.[5] The program was ex- refer patients to nearby health centers; and collect vital statistics.

pected to help accelerate the country’s progress in meeting Mil- HEWs are not allowed to administer antibiotics.[5]

lennium Development Goals (MDG) 4, 5 and 6 (reduce child

mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria One of an HEW’s first tasks is to recruit Voluntary Community

and other diseases).[6] Now it is the country’s major health Health Workers (vCHWs) to help implement HEP. These are in-

program: by 2010, there were 30,578 HEWs serving almost all dividuals who have had experience in community-based health

villages in rural areas where sedentary farming rather than no- services, such as those trained as community-based health work-

madism is the norm.[2] ers prior to HEP.

46 Peer Reviewed MEDICC Review, July 2011, Vol 13, No 3

Perspective

The first families to be trained are selected by the local govern- tion campaigns; and construction of sanitary facilities. Schools,

ment (kebele) administration, HEWs, vCHWs and community agriculture extension agents, community associations, as well

leaders based on criteria related to their earlier participation in as other social structures are involved in disseminating HEP

community health activities and readiness to enroll in the training. messages and promoting good health practices. Development

Women in the selected families take the lead role in the training, partners are encouraged to strengthen HEP implementation ac-

recognizing that women take more responsibility in family care. tivities, by providing health materials and supplies, training, and

Other families are selected for training when the first batch gradu- monitoring.

ates. Each group receives 96 hours of training, involving face-to-

face teaching and household visits in four modules correspond- HEP assumes that communities are owners, producers and mul-

ing to the four HEP subprograms: prevention of communicable tipliers of health. The roles of the health provider and other stake-

diseases, family health, environmental and household sanitation, holders are to enable households and communities to lead a

and health education. Formal training continues until all house- healthy life by (i) building their capacities and skills in disease pre-

holds graduate. HEWs and vCHWs follow up with households vention and health management; (ii) providing basic health tools

regularly. and commodities such as family planning methods, vaccines, oral

rehydration salts, community DOTS, and malaria drugs and nets;

(iii) attending childbirth; and (iv) providing timely referral to spe-

cialized care for those who need it.

Key Resources for Assessing HEP Impact

The Rapid Appraisal of Health Extension study was spon- WHAT HAS HEP DONE SO FAR?

sored by the L10K Project of John Snow International (JSI). Attribution of results to specific programs is always difficult be-

The study is based on qualitative data collected from four cause of the multiplicity of factors and actors in the social en-

vironment, but tangible improvements in key health indicators

major regions: Oromia, Tigray, Amhara and Southern Na-

have been observed since HEP’s implementation began,[2,13]

tions, Nationalities and Peoples Region.[7]

supporting our conclusion that HEP is an effective approach to

promoting good health in rural communities. It is now present in

The System Wide Effect of the Fund (SWEF) is a study

all rural agrarian areas and is being expanded to include pastoral-

sponsored by United States Agency for International De-

ist and urban areas.

velopment (USAID) to assess the effect of global health

initiatives, particularly of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS,

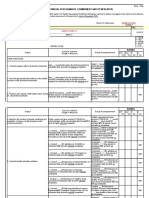

Credit for these improvements (Table 1) must be shared with

Tuberculosis and Malaria on national health systems and

global health initiatives that are major players in the implementa-

policy. Three rounds of SWEF studies have been con- tion of the health sector development program. The Global Fund

ducted between 2004 and 2010 by Abt Associates and to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; the President’s

MHRC.[8] Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief; and the World Bank have been

major players in health for the last ten years. This has helped the

The Good Health at Low Cost study is a five-country study work of the FMOH in HEP implementation.

coordinated by the London School of Hygiene and Tropical

Medicine and sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation. It

Table 1: Progress in key health indicators in Ethiopia, 2005–2010

selected five low-income countries, including Ethiopia, and

aimed to see how they have achieved good outcomes in Year

health.[9] 2005 (%) 2010 (%)

Primary health care coverage 76.9 90.0

Expanded Program of Immunization (EPI) 76.8 81.6

Contraceptive acceptance rate 37.9 56.2

The diffusion model assumes that change happens gradually. Antenatal coverage 50.4 67.7

As model families change their health practices, they influence

HIV prevalence 3.2 2.1

their neighbors and friends formally in venues such as commu-

nity meetings, and informally when they get together for social Source: Federal Ministry of Health, Ethiopia

activities such as coffee ceremonies and in idir and mahber,

community associations formed for mutual practical support Analyzing qualitative data collected from the L10K study, HEP’s

(the former for funeral services, the latter for activities such as main achievements (as expressed by those benefited) can be

harvesting and home-building). The social context gets modi- summarized as follows:[7]

fied by facilitating discussion of the content of the four HEP

modules. As HEP is implemented, household arrangement of HEP has created greater awareness of how to prevent com-

rooms and utensils and the availability of pit latrines change municable diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS

the physical structure of the household. One vCHW supervises and waterborne disease. Community members interviewed dur-

10 to 20 households and 70% of HEWs’ time is allocated to ing the L10K study reported that malaria is no longer epidemic.

household visits. They say that diarrhea and other waterborne diseases and eye

infections are decreasing:

HEP is an expression of the government’s political will regard-

ing health. All government sectors, local leaders, and com- Our children are no longer suffering from diarrhea, eye infec-

munities are required to collaborate in implementation of HEP tions and malnutrition. We keep them clean and feed them as

programs: health post construction; selection of vCHWs and per the advice given to us by the HEWs. (L10K: focus group

model families; mobilization of communities during immuniza- discussion, Tigray)

MEDICC Review, July 2011, Vol 13, No 3 Peer Reviewed 47

Perspective

Community and household attitudes toward HIV/AIDS and The diffusion model as an approach to health behavioral

those living with HIV/AIDS are changing, as have practices change is working. HEP’s impact is visible in the way people

related to prevention of infectious diseases in general. For live in their communities and from what local stakeholders

example, the L10K appraisal reported that communities and say:

households openly discussed HIV/AIDS and cared for those

living with the virus. Knowledge and behavioral practices to- They [HEWs] are influencing the community...teaching the

ward prevention of sexually transmitted infections have im- community. We used to suffer from different diseases. Now we

proved. Informants said that that their lifestyles have changed are learning to take preventive measures and we are not ex-

because of HEP: periencing any epidemics. (L10K: community leader, Oromia)

We learnt from HEWs that by doing simple things at home HEP has created synergy among public sector, community,

we can protect ourselves from diseases. Keeping our houses, and development partners. Local leaders, religious leaders, and

children and environment clean protects us from deadly dis- associations of youth, women and farmers actively participate

eases. These are simple things that anybody can do. Since during construction of pit latrines, vaccination, and community

we started keeping our homes clean, our children and family meetings. Development partners are assisting in the training of

members have become healthy. (L10K: focus group discus- HEWs and by supplying health posts with essential drugs and

sion participant, Southern Region) supplies. A development partner informant interviewed for the

L10K appraisal says:

Beneficiaries reported changed attitudes and behavioral

practices in preventive aspects of maternal and child health. HEP has created good ground for collaboration with partners.

Community informants and district and regional program coordi- During the implementation of health activities at the kebele

nators say that mothers and children are regularly monitored by [the smallest unit of government structure] level, development

HEWs. Access to family planning, antenatal and postnatal care partners participate in HEP in terms of finance, supply of com-

services has improved,[2] and maternal and childhood disease modities and materials, construction of health posts, and sup-

incidences have decreased as a result. plies of drugs and vaccines.

Disease incidence is minimized enormously, childhood and The government is encouraging partners in health to work at the

maternal deaths are reduced and the community has start- village level with the motto: All roads lead to the Health Extension

ed to use family planning programs efficiently; the number of Program!

women using contraceptives and accessing pre- and postna-

tal care services is increasing. (L10K: HEW, Amhara) CHALLENGES

Nevertheless, HEP has experienced some challenges. Gradua-

Community informants in the L10K study all agreed that infant tion of model families did not happen as planned. It was expected

feeding habits such as breast feeding and use of supplements

that within three years of implementation, all households would

have improved; the number of children and mothers immu-

have graduated;[15] however, due to travel time between house-

nized has increased, and practices in reporting sick children

holds and competing demands for family members’ time for farm-

to HEWs have shown improvement. The study team observed

ing activities, model family training is taking longer than antici-

such trends in the charts of the visited health posts. A commu-

pated.

nity informant says:

Also, use of voluntary community health workers appears hard

I really have benefited from HEP. I used to give birth every

to sustain without some material compensation for extra services

year. Now I breast feed, take contraceptives and avoid getting

rendered to communities. With the government’s policy of align-

pregnant [so often]. (L10K: community informant, Oromia)

ment of health activities, HEP is becoming the focal point of health

FMOH statistics on health and health-related indicators show that programming, so increasingly, development partners are also ex-

antenatal coverage increased from 67.7% in 2008–2009 to 71.4% ecuting their programs through HEP, creating heavier workloads

in 2009–2010 and postnatal coverage from 34.3% to 36.2% in the for HEWs. Although the increased integration is positive, HEW

same period.[14] burnout has been observed as a result.

HEP has improved sanitation and increased access to safe Career advancement is also a critical issue for HEWs and efforts

and clean drinking water from 35.9% in 2004–2005 to 66.2% are being made to address it.

in 2009–2010 nationally,[2] when access to safe excreta disposal

reached 60%. The research team of the L10K appraisal observed CONCLUSIONS

that households visited had pit latrines; separated animal sheds; Ethiopia’s HEP has shown tangible positive impacts on commu-

improved kitchens, bedrooms and living rooms; and cleanly man- nity health, in disease prevention, family health, and environmen-

aged drinking water and household goods. A community infor- tal hygiene and sanitation. The government has made HEP the

mant says: foundation of the country’s emerging new health system. Local

government and community participation is gaining momentum,

We have started drinking clean and safe water, keeping our and the roles and interests of development partners are crystalliz-

houses and environment clean, using pit latrines, separating ing. In order to strengthen HEP, FMOH has embarked on training

animal sheds from our homes, [and] using a separate kitchen. health officers and midwives. Cold storage for vaccines is also

(L10K: community informant, Tigray) being addressed through making refrigerators available.

48 Peer Reviewed MEDICC Review, July 2011, Vol 13, No 3

Perspective

HEP demonstrates that instead of sticking to traditional health villages and districts in Ethiopia. Ethiopian health officials expect

provider and medication-oriented models, context-sensitive and to meet MDGs 4 and 6 and to have made progress toward MDG

affordable functional models and approaches could be developed 5 by 2015.

to expand primary health care services. Development partners in

health were skeptical of HEP at first, but it has now proved to be a What is more important is that HEP has shown that population

more effective approach to preventing disease and instilling skills behavior patterns can be changed to be more favorable to good

and knowledge than the village clinic-based approach, which fo- health. With strong political will and a sense of purpose, low-

cused more on curative services with less attention to prevention. income countries can use innovative approaches to achieve

HEP is now at the center of global health initiatives directed to universal coverage of primary health care.

REFERENCES

1. Bachrach P. Revision and Finalization of the Affairs; 2008 [cited 2011 Apr 19]. 52 p. Available [G.C.2008/9]. Policy and Practice: information for

Program Action Plan of Ethiopia’s Health Sector from: http://www.undp.org.af/publications/Key action. Quarterly Health Bulletin. Addis Ababa:

Development Program [Internet]. Addis Ababa: Documents/MDG_Report_2008_En.pdf Federal Ministry of Health (ET); 2010.

Federal Ministry of Health (ET); 1998 Jul [cited 7. Banteyerga H, Kidanu A. Rapid Appraisal of 13. Health Sector Development Program III: Annual

2011 May 24]. 17 p. Available from: http://pdf. Health Extension program: Ethiopia Country Re- Performance Report [Internet]. Addis Ababa:

usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PDABR020.pdf port. Addis Ababa: The L10K project and MHRC; Federal Ministry of Health (ET); 2011 [cited 2011

2. Federal Ministry of Health (ET), Planning and 2008. May 24]. Available from: www.moh.gov.et/index.

Programming Department. Health and Health 8. Banteyerga H, Kidanu A, Hochkiss D, De S, php?option=com_remository&Itemid=59&func=

related indicators [Internet]. Addis Ababa: Fed- Tharaney M, Callaham K. The System Wide fileinfo&id=11

eral Ministry of Health (ET). 2004 Dec [cited Effects of the Scale Up of HIV/AIDs, Tuberculosis, 14. Federal Ministry of Health (ET). Office of Public

2011 May 24]. 59 p. Available from: http://cnhde. and Malaria Services in Ethiopia [Internet]. Relations. The Health Service Before and After

ei.columbia.edu/indicators/Health_Indicators96. Bethesda: Health systems 20/20 Project; 2010 1983 Ec (1991 GC): A summary of achievements

pdf Oct [cited 2011 May 24]. 89 p. Available from: from 1991 to 2010. Addis Ababa: Federal Minis-

3. UNICEF. Ethiopia Statistics. Basic Indicators 2009 www.ghinet.org/downloads/Ethiopia_SWEF_ try of Health (ET); 2010.

[Internet]. New York: UNICEF; 2010 [updated ReportOct_2010_FIN.pdf 15. Federal Ministry of Health (ET). Health Extension

2010 Mar 2; cited 2011 May 24]. Available from: 9. Banteyerga H, Kidanu A, Conteh L, McKee M. Implementation: Guide. Addis Ababa: Health Ex-

http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/ethiopia Ethiopia Chapter on Good health at Low Cost. tension Education Center; 2007.

_statistics.html A study conducted by LSHTM and Miz-Hasab

4. Abdela A. Maternal mortality trend in Ethiopia. Research Center, along with other four countries,

Ethiop J Health Dev [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2011 commissioned by the Rockefeller Foundation. THE AUTHOR

May 24];24(Special Issue 1):115–22. Available Forthcoming; 2011.

from: http://ejhd.uib.no/ejhd-v24-sn1/115%20 10. Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolly EE. Qualitative Meth- Hailom Banteyerga (hailombante@

Maternal%20Mortality%20Trend%20in%20 ods in Health: A field Guide for Applied research.

Ethiopia.pdf San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2005. yahoo.com), specialist in health policy

5. Federal Ministry of Health (ET). Health Exten- 11. World Health Organization. Declaration of and systems analysis with a doctorate in

sion Program in Ethiopia: Profile [Internet]. Addis Alma-Ata: International Conference on Primary education. Lead health researcher, Miz-

Ababa: Health extension and Education Cen- Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, Sept 6–12, 1978

ter; 2007 [cited 2011 May 24]. 27 p. Available [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization;

Hasab Research Center, Addis Ababa,

from: http://www.ethiopia.gov.et/English/MOH/ 1978 [cited 2011 May 24]. 3 p. Available from: Ethiopia.

Resources/Documents/HEW%20profile%20 http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_

Final%2008%2007.pdf almaata.pdf Submitted: April 5, 2011

6. United Nations. The Millennium Development 12. Roman T, Accorsi S, Akalu T, Vella V, Mamo D. Approved for publication: June 28, 2011

Goals Report 2008 [Internet]. New York: United Assessing the performance of the health sec-

Disclosures: None

Nations Department of Economic and Social tor: achievements and challenges in EFY 2001

MEDICC Review, July 2011, Vol 13, No 3 Peer Reviewed 49

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocumento15 páginas6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- HNSWDocumento13 páginasHNSWMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- System V Application Binary Interface: AMD64 Architecture Processor Supplement Draft Version 0.99.7Documento128 páginasSystem V Application Binary Interface: AMD64 Architecture Processor Supplement Draft Version 0.99.7Mulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Study On The Diversity..... The Fauna of The Ethiopian RegionDocumento246 páginasStudy On The Diversity..... The Fauna of The Ethiopian RegionMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Multivariate Morphometric Analysis of Honeybees (Apis Mellifera) in The Ethiopian RegionDocumento11 páginasMultivariate Morphometric Analysis of Honeybees (Apis Mellifera) in The Ethiopian RegionMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- 3Documento42 páginas3Mulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Intro To Linked ListDocumento9 páginasIntro To Linked ListMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Multivariate Morphometric Analysis of Honeybees (Apis Mellifera) in The Ethiopian RegionDocumento11 páginasMultivariate Morphometric Analysis of Honeybees (Apis Mellifera) in The Ethiopian RegionMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- EthiopiaDocumento47 páginasEthiopialebor sawihseyAinda não há avaliações

- AmharicDocumento11 páginasAmharicMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Lab 1Documento8 páginasLab 1Mulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- 973ethiopia PDFDocumento73 páginas973ethiopia PDFMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- 7.2 Memory Coherency and Protocol: 24593-Rev. 3.12-September 2006 AMD64 TechnologyDocumento4 páginas7.2 Memory Coherency and Protocol: 24593-Rev. 3.12-September 2006 AMD64 TechnologyMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- ES3N: A Semantic Approach To Data Management in Sensor NetworksDocumento13 páginasES3N: A Semantic Approach To Data Management in Sensor NetworksMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Sonuma Asplos14Documento15 páginasSonuma Asplos14Mulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Albert Einstein. 1879-1955. A Biographical Memoir by John Archibald WheelerDocumento23 páginasAlbert Einstein. 1879-1955. A Biographical Memoir by John Archibald Wheelergbabeuf100% (1)

- CACTI 3.0: An Integrated Cache Timing, Power, and Area ModelDocumento40 páginasCACTI 3.0: An Integrated Cache Timing, Power, and Area ModelMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Keyboard Layouts WindowsDocumento6 páginasKeyboard Layouts WindowsMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- NUMADocumento4 páginasNUMADaiyan ArifAinda não há avaliações

- A Novel Image Median Filtering Algorithm Based On Incomplete Quick Sort AlgorithmDocumento6 páginasA Novel Image Median Filtering Algorithm Based On Incomplete Quick Sort AlgorithmMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- Unicode StandardDocumento79 páginasUnicode StandardMulugeta AbebawAinda não há avaliações

- B+ TreesDocumento8 páginasB+ Treesbyrusber100% (3)

- ERF IMC3 IMC4 Evaluation ENGDocumento4 páginasERF IMC3 IMC4 Evaluation ENGNsabimana PatrickAinda não há avaliações

- Exercise12 PDFDocumento17 páginasExercise12 PDFHayna RoseAinda não há avaliações

- Make Every Step Count.: Easy Health Individual Health Insurance PlanDocumento8 páginasMake Every Step Count.: Easy Health Individual Health Insurance PlanAakash MiraniAinda não há avaliações

- Family Law AidsDocumento16 páginasFamily Law AidsThe Motivated GeekAinda não há avaliações

- Substance Abuse Treatment and Care For WomenDocumento107 páginasSubstance Abuse Treatment and Care For WomenLjilja Taneva100% (1)

- Global Fund Report On The Country Coordinating Mechanism ModelDocumento60 páginasGlobal Fund Report On The Country Coordinating Mechanism ModelKataisee RichardsonAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 11 SummaryDocumento6 páginasChapter 11 SummarydimputhomasAinda não há avaliações

- BMC Public HealthDocumento21 páginasBMC Public HealthDaniel JhonsonAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines For PMDT in India - May 2012Documento199 páginasGuidelines For PMDT in India - May 2012smbawasainiAinda não há avaliações

- Standards of Care in Child Care InstitutionsDocumento36 páginasStandards of Care in Child Care InstitutionsVaishnavi JayakumarAinda não há avaliações

- On MCH and Maternal Health in BangladeshDocumento46 páginasOn MCH and Maternal Health in BangladeshTanni ChowdhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledDocumento12 páginasIndividual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledTiffanny Diane Agbayani RuedasAinda não há avaliações

- Guidelines On Food Fortifcation With Micronutrients9241594012 - EngDocumento376 páginasGuidelines On Food Fortifcation With Micronutrients9241594012 - EngjolyaberryAinda não há avaliações

- Curriculum Vitae Alvin SaputraDocumento5 páginasCurriculum Vitae Alvin SaputraAlvin SaputraAinda não há avaliações

- 4th BMBLDocumento270 páginas4th BMBLpmholiveiraAinda não há avaliações

- CDC - Malaria - About Malaria - HistoryDocumento5 páginasCDC - Malaria - About Malaria - Historyapi-286232916Ainda não há avaliações

- The Study BeginsDocumento4 páginasThe Study BeginsBimby Ali LimpaoAinda não há avaliações

- Dengue Fever and Other Hemorrhagic Viruses (Deadly Diseases and Epidemics) - T. Chakraborty (Chelsea House, 2008) WW PDFDocumento103 páginasDengue Fever and Other Hemorrhagic Viruses (Deadly Diseases and Epidemics) - T. Chakraborty (Chelsea House, 2008) WW PDFLavinia GeorgianaAinda não há avaliações

- Katzenberg, LovellDocumento9 páginasKatzenberg, Lovellmartu_kAinda não há avaliações

- Epidemiology Prevention & Control of Malaria: Dr. Neha Tyagi Assistant Professor Department of Community MedicineDocumento29 páginasEpidemiology Prevention & Control of Malaria: Dr. Neha Tyagi Assistant Professor Department of Community MedicineShashi TyagiAinda não há avaliações

- Profile and CV of SbabaDocumento8 páginasProfile and CV of SbabaOlukayode SoremekunAinda não há avaliações

- Employment Application FormDocumento3 páginasEmployment Application FormLenny PangAinda não há avaliações

- TR - Male CircumcisionDocumento82 páginasTR - Male Circumcisionzulharman79Ainda não há avaliações

- Malaria: Priti Thakur Leena PestonjiDocumento32 páginasMalaria: Priti Thakur Leena PestonjiPriti ThakurAinda não há avaliações

- Saint Louis University National Service Training ProgramDocumento83 páginasSaint Louis University National Service Training ProgramChristine Mae VeaAinda não há avaliações

- Mapeh 10 ExamDocumento4 páginasMapeh 10 ExamNepthali Agudos Cantomayor67% (3)

- Retrograde Autologous Priming of Cardiopulmonary Bypass CircuitDocumento18 páginasRetrograde Autologous Priming of Cardiopulmonary Bypass CircuitMuhammad Badrushshalih100% (2)

- Ntcp-Mop TB CPG 2015Documento192 páginasNtcp-Mop TB CPG 2015Val Constantine Say CuaAinda não há avaliações

- Tackling HIV/AIDS and Malaria in PregnancyDocumento8 páginasTackling HIV/AIDS and Malaria in PregnancyCecilia McCallumAinda não há avaliações

- PHC ChecklistDocumento15 páginasPHC ChecklistNarendra KardileAinda não há avaliações