Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Jurnal SP

Enviado por

Leny LukitasariTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Jurnal SP

Enviado por

Leny LukitasariDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CONTINUING EDUCATION

Preoperative Care of Children:

Strategies From a Child Life

Perspective 1.7 www.aornjournal.org/content/cme

JUDY J. PANELLA, BS, CCLS

Continuing Education Contact Hours Accreditation

indicates that continuing education (CE) contact hours are AORN is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing

available for this activity. Earn the CE contact hours by reading education by the American Nurses Credentialing Center’s

this article, reviewing the purpose/goal and objectives, and Commission on Accreditation.

completing the online Examination and Learner Evaluation at

http://www.aornjournal.org/content/cme. A score of 70% correct Approvals

on the examination is required for credit. Participants receive

This program meets criteria for CNOR and CRNFA recerti-

feedback on incorrect answers. Each applicant who successfully fication, as well as other CE requirements.

completes this program can immediately print a certificate of

completion. AORN is provider-approved by the California Board of

Registered Nursing, Provider Number CEP 13019. Check

Event: #16524 with your state board of nursing for acceptance of this

Session: #0001 activity for relicensure.

Fee: For current pricing, please go to: http://www.aornjournal

.org/content/cme.

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures

The contact hours for this article expire July 31, 2019. Judy J. Panella, BS, CCLS, has no declared affiliation that

Pricing is subject to change. could be perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest

in the publication of this article.

The behavioral objectives for this program were created by

Purpose/Goal Kristi Van Anderson, BSN, RN, CNOR, clinical editor, with

To provide the learner with knowledge specific to develop- consultation from Susan Bakewell, MS, RN-BC, director,

mentally appropriate preoperative care of children. Perioperative Education. Ms Van Anderson and Ms Bakewell

have no declared affiliations that could be perceived as posing

potential conflicts of interest in the publication of this article.

Objectives

Sponsorship or Commercial Support

1. Explain the role of the child life specialist.

No sponsorship or commercial support was received for this article.

2. Discuss the role of the perioperative nurse in decreasing

preoperative parental and child anxiety.

3. Describe strategies for providing developmentally Disclaimer

appro-priate care to infants, children, and adolescents. AORN recognizes these activities as CE for RNs. This recognition

4. Describe strategies for providing care to children with does not imply that AORN or the American Nurses Credentialing

developmental delays. Center approves or endorses products mentioned in the activity.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2016.05.004

ª AORN, Inc, 2016

www.aornjournal.org AORN Journal j 11

Preoperative Care of Children:

Strategies From a Child Life

Perspective 1.7 www.aornjournal.org/content/cme

JUDY J. PANELLA, BS, CCLS

ABSTRACT

The experience of surgery can be extremely stressful for children and their family members. Many

children’s hospitals offer a formal surgical preparation program to patients and their families, usually

led by a child life specialist. However, smaller hospitals or ambulatory surgery centers may not be

able to use this approach to preparing children for surgery. In this scenario, the perioperative nurse

is in the ideal position to provide developmentally appropriate surgical preparation and education at

the bedside. Knowledge of normal child development and age-appropriate diversional activities are

necessary to implement an effective surgical preparation program. This age-appropriate prep-

aration can help facilitate a positive medical experience that can reduce anxiety and affect the

child’s and his or her family’s view of future medical encounters. AORN J 104 (July 2016) 12-19.

ª AORN, Inc, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2016.05.004

Key words: pediatric, preoperative, age-appropriate preparation, child life, coping.

T he experience of surgery, including its unfamiliar routines,

clothing, sights, sounds, and smells, can be extremely

parental anxiety may perpetuate high anxiety in the child,

so it is important to address the fears and concerns of the

stressful for children and their family child’s family members and involve them in the child’s

members. Nurses caring for children preoperatively must be 2,3,5

care. If a patient or family member is made to feel that

prepared to provide developmentally appropriate care to help his or her reactions are abnormal or that the surgical

relieve the anxiety of children and the children’s family experience should be “easy,” medical personnel can be

1 perceived as demeaning and unsupportive.

members. Allowing time for age-appropriate preoperative

preparation activities and involving the child’s parents or

Most major medical centers and children’s hospitals have child

caregivers in the process may benefit the child by reducing

2 3 life departments that provide formal surgical preparation

anxiety. Fortier et al found that preventing preoperative anxiety

programs, generally led by child life specialists. A child life

in children may help prevent negative outcomes after surgery,

specialist is a trained professional who has experience helping

such as negative behavioral changes and postoperative pain.

children and family members cope with health care experi-ences.

Because anxiety may have a substantial effect on a patient’s well-

Child life specialists often meet children and adolescents during

being, it is important to understand that a single experience can

preoperative testing appointments to help explain anesthesia and

drastically shape how a child views future medical visits and

encounters with health care professionals. surgery in developmentally appropriate terms. This may include

providing preoperative tours and facilitating medical play to

Perioperative anxiety in both children and their family mem- promote familiarization and mastery of unfa-miliar and often

4 scary equipment. Ideally, children should

bers is a normal aspect of the surgical experience. High

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aorn.2016.05.004 ª

AORN, Inc, 2016

12 j AORN Journal www.aornjournal.org

July 2016, Vol. 104, No. 1 Preoperative Care of Children

meet the child life specialist for age-appropriate alterations in their care to provide adequate preparation while

preparation anywhere from 24 hours to several days before performing preoperative assessments and tasks. However,

a planned surgical event. Although younger children may some planning is required to institute effective diversional and

benefit from preparation closer to the date of surgery to educational interventions that can improve the surgical expe-

avoid building anxiety, adolescents may benefit from rience for children and their family members. Gathering

preparation at least 7 to 10 days in advance.4 appropriate medical equipment such as an IV catheter with

extension tubing, blood pressure cuff, stethoscope, anesthesia

A small hospital or ambulatory surgery center may not employ a mask, or electrocardiogram (ECG) leads that are clearly

child life specialist, and children may arrive with little to no labeled for teaching purposes can serve as excellent show and

formal preparation for a surgical or anesthetic event. The surgical tell items for what children may see or experience during their

and anesthesia team explains the surgical process and anesthesia visit (Figure 1). Books, bubbles, handheld games or tablets,

sequence to children and family members in this situation. and light-up or musical toys can also be kept in a box on the

However, the perioperative nurse remains a consis-tent and unit and used as diversional activities for children of different

trusted presence throughout the preoperative period and should developmental ages. These materials must be thoroughly

understand how to help children and their family members cope cleaned according to the facility’s infection control policy

with preoperative anxiety. When preoperative preparation by a between uses. Suggested interventions that the perioperative

child life specialist cannot be provided, perioperative nurses are nurse can implement to support children and their family

in the best position to assist children and family members in members throughout their surgical experience are described

coping with the surgical environment and its routines. Depending by age group in the following sections.

on the information that has been provided by the surgeon at a

clinic visit and the independent research family members or

patients may have performed on their own, children can arrive

Preparing Infants and Toddlers

Preparing the parents of neonates (birth to 27 days old), in-

with varying levels of under-standing and misconceptions about

fants (28 days to one year old), and toddlers (one year to two

surgery. An in-depth knowledge of development can guide nurses 7

and other pro-viders to deliver age-appropriate care that can years old) for what to expect before a procedure and how

enhance chil-dren’s ability to cope effectively with a stressful they can help care for their children may lead to lower stress

8

situation and create an atmosphere that promotes positive coping levels for both the parents and the children. Validating a

for future medical experiences. A summary of the developmental parent’s fears and concerns and providing supportive listening

norms and implications to consider for the preparation of can be helpful in reducing parent stress, thus reducing patient

children and adolescents undergoing a surgical or anesthetic

stress. If the situation seems appropriate, using humor can

sometimes be a starting point to build rapport with parents.

event is provided in Table 1.

If there is communication with caregivers before the day of

surgery, the nurse should remind parents to bring comfort

When preparing the child for surgery, the role of the parent or items (eg, a blanket that smells like home, pacifier, favorite

caregiver cannot be overstated. Nurses must be aware that stuffed animal, familiar bottle and nipple for use in recovery)

preoperative preparation relies on developing a collaborative that can aid in coping and help address issues related to a

relationship with the caregiver. The presence and involvement 1

change in environment and routine. Because separation from

of a parent or caregiver can help normalize the hospital envi- caregivers is the primary source of stress for this age group,

6

ronment for the child, provide support, and reduce stress. parents should be encouraged to remain with their children

4

Nurses can use their knowledge of development to teach whenever feasible. Parents should be at their children’s

parents or caregivers coping strategies to use with the child bedside in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) as quickly as

during the preoperative and postoperative periods. This article 4

medically possible to decrease separation anxiety. Informing

provides developmentally appropriate interventions nurses parents of the anesthesia and surgical sequence, postoperative

can use to improve the surgical experience for children and dressings, and monitoring equipment may help decrease some

their family members. of their anxiety, thus creating a calmer environment for their

children.

DEVELOPMENTALLY APPROPRIATE

SURGICAL PREPARATION Infants and toddlers likely do not benefit from a direct

By taking into consideration the child’s developmental level explanation of a surgical procedure. Infants rely on their

and the associated parental concerns, nurses can make parents to meet their needs and may be soothed preoperatively

www.aornjournal.org AORN Journal j 13

Panella July 2016, Vol. 104, No. 1

1-5

Table 1. Developmental Considerations When Caring for Children Undergoing Surgery

Age Developmental Considerations Implications of Medical Experiences

Neonatal/infancy: birth to 1 year Learn through senses and motor Separation anxiety

movements Lack of stimulation

Reliant on caregivers for basic needs, Disruption of sleeping and feeding routine

building trust with caregivers

Toddlerhood: 1-2 years Interact with environment through senses Separation anxiety

Begin seeking autonomy Fear forced dependence

Developing free will Distractions during medical care may

reduce anxiety (songs, toys)

Early childhood (preschoolers): Language and social skills are Fear of mutilation and pain

2-5 years developing Developing symbolic thought Misconceptions regarding surgery

Seeking initiative; want to assert control Separation anxiety

over their world May view surgery as punishment for some

Primarily perceptive thinkers; wrongdoing

reasoning may be distorted Do not have an understanding of the

Feel remorse for inappropriate actions body’s organs

Middle childhood (school-aged Acquire capacity for rational, logical Fear the unknown, loss of control

children): 6-11 years thought and abstract thinking Fear of bodily injury and pain, especially

Gain the capacity for hypothetical and intrusive procedures in the genital area

deductive reasoning Fear of illness and disability

Gain the ability to understand rules, the Better tolerance for separation anxiety, but

concept of fairness, and cooperation with still present

others Misconceptions about surgery may still be

Gain mastery and sense of competence present, may still see surgery as

by demonstrating knowledge and skills punishment

(like to be involved in care)

Early adolescence: 12-18 years Rapidly maturing physically Fear of bodily injury, death, and pain

and emotionally Fear of loss of identity and control

Developing one’s own identity Concerned about body image, may worry

Progressing toward mature thinking and about cosmetic implications of surgery

abstract thought Concern about peer group status after

Better able to understand causation of surgery or hospitalization

disease

Value privacy, independence

Peer relationships are of

supreme importance

References

1. Difusco LA. Pediatric surgery. In: Rothrock JC, ed. Alexander’s Care of the Patient in Surgery. 15th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 2015:1008-1080.

2. McLeod S. Erik Erikson. Simply Psychology. http://www.simplypsychology.org/Erik-Erikson.html. Published 2008. Updated 2013. Accessed

April 7, 2016.

3. Harris TB, Sibley A, Rodriguez C, Brandt ML. Teaching the psychosocial aspects of pediatric surgery. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2013;22(3):161-166.

4. McLeod S. Jean Piaget. Simply Psychology. http://www.simplypsychology.org/piaget.html. Published 2009. Updated 2015. Accessed

April 7, 2016.

5. Leack KM. Perioperative preparation of the child and family. In: Tkacz Browne N, Flanigan LM, McComiskey CA, Pieper P, eds. Nursing

Care of the Pediatric Surgical Patient. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013:3-16.

with gentle rocking, pacifiers, and warm blankets. Infants and assessments can be helpful in gaining trust and cooperation.

toddlers interact with their environment through their senses For example, stating “I need to check your blood pressure;

1

and therefore may benefit from music or toys for distraction. this is the cuff,” and allowing the toddler to hold and play

Toddlers may also benefit from hands-on manipulation of with the cuff before placing it on the arm or leg may be

appropriate medical equipment (eg, blood pressure cuff, beneficial. Hearing the words and modeling can help gain

1,9

anesthesia mask). Using simple words and allowing the cooperation during an examination: “I need to listen to your

toddler to hold and explore equipment used during heart; how about I listen to Mom’s heart first?” Infants and

14 j AORN Journal www.aornjournal.org

July 2016, Vol. 104, No. 1 Preoperative Care of Children

comfortable sitting on his or her lap. The nurse should try to

elicit from the parent the understanding of the child regarding

the reason he or she is at the hospital. Determining the child’s

point of reference can be helpful in proceeding with

additional explanation. For example: “I understand you are

here today because you have been getting a lot of sore throats

and your tonsils are causing some trouble.” It is important to

use the correct anatomic term for body parts and medical

equipment in addition to child-friendly descriptors to help

provide extra explanation. For example: “This is the pulse

oximeter; it checks your oxygen and how your heart is

beating. It is a sticker that wraps around your finger or toe and

has a red light inside.”

Preschool children may be frightened by surgical attire and

4

experience distress related to separation from caregivers.

The nurse should encourage parents to be present and

involved in as much of the preoperative and postoperative

process as medically possible. It may be appropriate to

give the parent and the child a surgical hat and mask to

wear and play with to help normalize the environment.

Remind the child that when the doctor works on his or her

body, he or she will be asleep with anesthesia (ie, “hospital

sleeping medicine”) and will not feel anything the doctor is

doing until it is time to wake up.

Figure 1. A box of medical supplies clearly labeled for

teaching purposes only that is easily accessible in the Allowing preschoolers to explore and manipulate appropriate

preoperative space can hold “show and tell” items. medical equipment can lead to familiarization and may

1

toddlers may use their parents as barometers for how they decrease stress. Modeling by performing a blood pressure or

should feel about a situation.10 If a parent appears calm temperature check on a parent can be helpful in gaining

and compliant with a nurse, the child may demonstrate the cooperation from the child. If the child brings a stuffed

same behavior. animal, always ask permission first before listening to

“Fluffy’s” heart. Reminders about postoperative dressings and

the “surgery spot” (ie, incision) can be helpful. The

Preparing Preschoolers preschooler should be prepared for a sore spot but should be

Children in early childhood (ie, preschool children ages two reminded that it will get better. Reinforce the times and places

7 that parents or caregivers will be present with the child.

to five years) have verbal abilities, and it is important to

understand the tendency of the child to misinterpret words

4

and concepts that require abstract thinking. For example, Preparing Children in Middle Childhood

using terms such as “gas” anesthesia or saying “we are going Children in middle childhood (school-aged children between

to put you to sleep” can often be misunderstood. Instead try 7

language and explanation, such as “medicine air” or “hospital 6 and 11 years old) should have a greater capacity than

medicine sleep that is different from sleep you have at home.” toddlers or preschoolers to tolerate separation from caregivers

Preschoolers may believe they did something wrong to and are increasingly able to understand the concepts of

4

deserve what is happening to them. Explaining to children illness. A school-aged child should have some degree of

that they had no role in causing their illness will decrease understanding about the surgical procedure on arrival at the

4 hospital or surgical center. Children in this age group gain a

guilt and worry about punishment.

sense of competence by demonstrating their knowledge and

When assessing a patient in this age group, the nurse should skills. An effective way to elicit information is simply to ask.

preferably sit at the child’s eye level. Children may be more For example: “Tell me what you know about why you are here

cooperative when remaining close to a parent and may be most today” can be a great starting point. It is important to

www.aornjournal.org AORN Journal j 15

Panella July 2016, Vol. 104, No. 1

direct this question to the child rather than the parent.

Children in this age group have had more exposure to media

6

and peer influence, which can lead to misconceptions or

worries of not waking up from anesthesia or awakening

during surgery. Using clear language and explaining the

differences between sleep at home and “hospital sleeping

medicine” can be quite helpful.

Because children in this age group fear the unknown,

illness, and bodily harm,1,6 a concern that sometimes arises

with school-aged children related to anesthesia is what

they will or will not remember. When the patient hears

“you won’t remember anything,” particularly when

describing a preoper-ative medication, patients may fear

they will wake up not remembering their name, family

members, or fundamental traits about themselves.

Pictures and other visual aids are particularly effective in

explaining surgery to this age group. A simple children’s

anatomy book can be useful for visual learners and help

reinforce medical explanations. At this age, some children

may just be beginning to understand that organs and body

systems are complex entities, but unseen body functions

may need to be explained by the nurse. 1 Younger children

in this age range may still think their heart is similar to

what they see on Valentine’s Day cards and may generalize Figure 2. A doll with a cast or bandage may show

the term “stomach” to their entire abdomen (“tummy” or children how their “surgery spot” may appear after

“belly”). Using an anatomy book can help children gain a surgery.

more accurate understanding of their body, the size and

location of the surgical site, where to look for the incision asking school-aged children to help develop their own

after the surgery, or why they will not be able to see the coping strategies can be helpful in supporting their

surgical site after surgery. Creating a flip book of pictures independence. Help them choose from several options; for

containing common surgical sites, such as the tonsils, example: “Some kids like to watch me start the IV, others

adenoids, and ear canal, can be helpful for both children like to look away or listen to music on their phones, and

and parents. If a facility has a high rate of orthopedic others like to hold their mom’s or dad’s hand. Which do

procedures and casting, having a doll that is casted can be you think would help you most?”

a great visual for what to anticipate (Figure 2).

Allowing the child appropriate choices and opportunities to be Preparing Adolescents

involved in his or her care can often lead to better coopera- The nurse may encounter a wide range of emotions and be-

1 7

tion. Telling the child, “I have to check your temperature and haviors from early adolescents (12 to 18 years). Adolescents

blood pressure and listen to your heart and lungs” and then 11

fear a loss of self-control and autonomy and therefore may

asking, “Which would you like me to do first?” is an example react negatively to being told what to wear (ie, hospital gown),

of how to offer an appropriate limited choice. Asking “yes” or how to behave (ie, answering questions related to their medical

“no” questions such as “Can I check your temperature?” allows history, discussing uncomfortable or private topics), or to

the child to say “no,” placing the nurse in a difficult situation. maintain NPO status by withdrawing or not cooperating with the

The temperature must be obtained regardless, violating the health care team. Many of the strategies used for younger

trust the nurse is building with the child. Consider allowing children also work for adolescents, with a few modifications and

the child to perform simple tasks, such as removing his or her additions. Address the adolescent patient, rather than the parents,

own ECG leads in the PACU, to help the child feel more from the beginning of the check-in process to support their desire

involved in his or her care. Also, 4

for independence. Many adolescents

16 j AORN Journal www.aornjournal.org

July 2016, Vol. 104, No. 1 Preoperative Care of Children

should be able to answer most, if not all, of the interview challenging for those with developmental delays or a sensory

questions related to allergies, NPO status, and pain scores. processing disorder (eg, autism spectrum disorder). As with

It can be easy for a parent to take over the conversation, any disorder, the patient’s impairments may fall at different

which may cause the adolescent patient to withdraw. points on a spectrum. A child or teen could have minimal

impairment in only one or two domains of development, such

Peer relationships are of supreme importance to as social interactions and language, or have significant deficits

adolescents. Allowing the adolescent access to their phone across multiple domains that greatly affect their cognitive

to text friends can help them feel connected to their peer 12

under-standing. For this reason, the nurse should not make

group. Setting ground rules from the beginning, reminding

assumptions about the patient’s abilities based on the

the adolescent that he or she may keep the phone in the

diagnosis listed in the chart. Another factor to consider,

preoperative or postoperative area but must still attend to

especially in children with autism spectrum disorder, is that

the discussion and answer questions when asked by the

many are concrete thinkers and may not understand abstract

health care team, is essential. Playing a favorite game or

thoughts or common idioms such as “frog in your throat.” A

phone application can help distract adolescents and

child may literally picture themself swallowing a frog.

normalize the situation, which can lower anxiety and help

Sensory integration is also an important consideration.

11

reduce the need for preoperative anxiolytic medication. Sometimes, the noise level or brightness of the lights may be

a negative trigger. Emotional regulation can be extremely

The adolescent should have had a role in the surgical 13

decision-making process and have an understanding of the challenging for this group of patients.

need and indications for surgery. Even so, teens can still A hospitalization or surgical procedure may provoke chal-

benefit from more detailed explanations and visual aids. lenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder.

Many adolescents are interested in science and the human These behaviors can include aggression, tantrums, hitting,

body. Using anatomy books or diagrams can be useful in 13

helping the teen become more comfortable and provides an kicking, biting, and scratching. The challenge is delivering

opportunity to ask questions. Common concerns for this care in an effective, safe manner. Family-centered care

age group may include an altered body image, peer rejec- principles, such as acknowledging parents and caregivers as

the experts about their children and involving them in the

tion, disability, loss of control, and fear of death. 1 When

development of an optimal care plan, are crucial when

addressing these concerns, the nurse should not dismiss the

planning interventions for any child, but they are especially

teen’s worries because a question may be difficult to

important when caring for children with special needs or

answer. This does not allow the adolescent to feel as if his

developmental delays. It is advisable to try to speak privately

or her concerns are heard and validated. When answering

with a parent first to determine the most effective approach for

questions, an honest approach can be helpful in building

the child. Parents know their child’s likes and dislikes, trigger

rapport.

words and behaviors, and communication preferences and

Because of heightened concerns about body image, interventions that have helped redirect challenging behaviors

adolescents are often extremely worried about the resulting in the past and can lead to more compliance from the patient.

Some questions to consider when talking with parents include

cosmetic effects of an operation.4 They may seem more

the following:

concerned about what their scar will look like than the

actual surgical and anesthesia process. Validating these

concerns without judgment or minimizing them can lead to What is the child’s level of understanding regarding the

more effective cooperation and conversation. Adolescents procedure?

also value their privacy, and the nurse should be especially What interventions have worked well during past

mindful of this.1 For example, if the adolescent needs to medical encounters?

use the restroom, offer an additional gown to wear around How does the child communicate (verbally or

the back to help him or her feel more covered. Inform nonverbally)? Does he or she use any communication

teens about who will need to examine them and why. devices (eg, picture cards)?

Is the child sensitive to touch or noise?

Are there any items of fixation or self-stimulating

Children With Developmental Delays behaviors that the child uses?

Medical experiences can be stressful for many children who What strategies work best for transitions such as moving

fall within developmental norms, but can be much more 12

rooms or separation from a caregiver?

www.aornjournal.org AORN Journal j 17

Panella July 2016, Vol. 104, No. 1

13

alarms are still audible for the nurse. The best strategy to

Resources for Pediatric Surgical Patients and keep in mind is individualized care. Every child is

Their Family Members different, and strategies that worked for one patient with a

Bhatia S. The Surgery Book: For Kids. Bloomington, IN: developmental challenge may not work for the next.

AuthorHouse; 2010.

Colombo L. Uncover the Human Body: An Uncover It CONCLUSION

Book. San Diego, CA: Silver Dolphin Press; 2003. Understanding the interaction of development and the

potential psychosocial effect of surgery helps providers

Duncan D. When Molly Was in the Hospital: A Book address the common concerns and fears experienced by

for Brothers and Sisters of Hospitalized Children. children and their family members. Optimal care is provided

Windsor, CA: Rayve Productions, Inc; 1994. when the medical team understands and respects the child’s

develop-mental level, includes family members and

Kids worry too: a guide for adults helping children

caregivers in decision making, and works to create a positive

understand hospitalization. Nebraska Medicine. http://

medical experience. The strategies presented in this article are

www.nebraskamed.com/app_files/pdf/childlife/kids-

not intended to increase the nurses’ workload in an already

worry .pdf. Accessed April 7, 2016.

busy and fast-paced perioperative work environment. Rather,

Matt M, Ziemian J. Human Anatomy Coloring Book. they are meant to provide the reader with effective

Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, Inc; 1982. interventions that can be practically implemented by nurses

and positively affect children and their family members. In

the future, more research on outcomes associated with quality

preoperative preparation, such as improved pain management

When the child arrives, if more than one caregiver is present, it and decreased anxiety, is necessary to gain a better

may be possible to complete many of the admission questions understanding of the benefits associated with these strategies.

with one parent or caregiver while the child remains in a space

where he or she may be more comfortable, such as in the waiting

room, with another caregiver. For children who have had References

1. Difusco LA. Pediatric surgery. In: Rothrock JC, ed. Alexander’s

multiple medical encounters, being in a preoperative holding

Care of the Patient in Surgery. 15th ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby;

room may produce anxiety. Although there is clearly an

2015:1008-1080.

indication for the child to know or have some understanding of

2. Perry JN, Hooper VD, Masiongale J. Reduction of preoper-

what is happening during the surgical encounter, what is often

ative anxiety in pediatric surgery patients using age-

most helpful with this population is to simply manage the appropriate teaching interventions. J Perianesth

environment. Upon meeting the child, speak softly and slowly Nurs. 2012;27(2):69-81.

and allow time for the patient to process information and 3. Fortier MA, Del Rosario AM, Martin SR, Kain ZN. Perioperative

respond. Depending on a patient’s developmental level, it may anxiety in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20(4):318-322.

not be sensible to engage in a detailed preparation discussion, but 4. Harris TB, Sibley A, Rodriguez C, Brandt ML.

simple pictures of spaces or reminders about a “sore surgery spot” Teaching the psy-chosocial aspects of pediatric

13 surgery. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2013; 22(3):161-166.

or “place the doctor is going to fix” may be sufficient. For some 5. Chorney JM, Kain ZN. Family-centered pediatric

children, saying the word “no” can provoke a tantrum. Remove perioperative care. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(3):751-755.

unnecessary equipment from the patient’s room if possible and 6. Leack KM. Perioperative preparation of the child and family. In:

keep supplies and materials out of view until just before use to Tkacz Browne N, Flanigan LM, McComiskey CA, Pieper P,

13 eds. Nursing Care of the Pediatric Surgical Patient. 3rd

avoid triggering tantrums or other challenging behaviors. For

ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2013:3-16.

example, if the nurse is setting up supplies to start an IV, it may

7. Williams K, Thomson D, Seto I, et al; StaR Child

be helpful to collect the tourniquet, alcohol swabs, IV catheter, Health Group. Standard 6: age groups for pediatric

and tape on a treatment tray outside the room and roll it in just trials. Pediatrics. 2012; 129(suppl 3):S153-S160.

before the procedure. If noises or lights trigger difficult behaviors 8. Fincher W, Shaw J, Ramelet AS. The effectiveness of a stand-

in a patient, keep environmental stimuli to a minimum and offer ardised preoperative preparation in reducing child

to turn down lights or reduce volume on alarms, but ensure and parent anxiety: a single-blind randomised

controlled trial. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(7-8):946-955.

18 j AORN Journal www.aornjournal.org

July 2016, Vol. 104, No. 1 Preoperative Care of Children

9. Ahmed MI, Farrell MA, Parrish K, Karla A. Preoperative anxiety in 13. Johnson NL, Rodriguez D. Children with autism spectrum

children: risk factors and non-pharmacological management. disorder at a pediatric hospital: a systemic review of the

Middle East J Anaesthesiol. 2011;21(2):153-164. literature. Pediatr Nurs. 2013;39(3):131-141.

10. Lieberman AF, Van Horn P. Psychotherapy With Infants and

Young Children: Repairing the Effects of Stress and Trauma

on Early Attachment. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008.

11. Lee JH, Jung HK, Lee GG, Kim HY, Park SG, Woo SC. Effect of behavioral Judy J. Panella, BS, CCLS, is a child life specialist at

intervention using smartphone application for preoperative anxiety in Duke Children’s Hospital and Health Center, Durham, NC.

pediatric patients. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;65(6):508-518. Ms Panella has no declared affiliation that could be

perceived as posing a potential conflict of interest in the

12. Scarpinato N, Bradley J, Kurbjun K, Bateman X, Holtzer B, Ely B.

publication of this article.

Caring for the child with an autism spectrum disorder in the

acute care setting. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2010;15(3):244-254.

www.aornjournal.org AORN Journal j 19

EXAMINATION

Continuing Education:

Preoperative Care of Children:

Strategies from a Child Life

Perspective 1.7 www.aornjournal.org/content/cme

PURPOSE/GOAL

To provide the learner with knowledge specific to developmentally appropriate preoperative care of

children.

OBJECTIVES

1. Explain the role of the child life specialist.

2. Discuss the role of the perioperative nurse in decreasing preoperative parental and child anxiety.

3. Describe strategies for providing developmentally appropriate care to infants, children, and adolescents.

4. Describe strategies for providing care to children with developmental delays.

The Examination and Learner Evaluation are printed here for your convenience. To receive

continuing education credit, you must complete the online Examination and Learner Evaluation at

http://www.aornjournal.org/content/cme.

QUESTIONS position to assist children and family members in

1. A child life specialist is a trained professional who has coping with the surgical environment.

experience helping children and their family members a. true b. false

cope with health care experiences.

4. To institute effective educational and diversional in-

a. true b. false

terventions for children undergoing surgery,

perioperative nurses may consider gathering appropriate

2. Child life specialists often meet children and

medical sup-plies for “show and tell,” such as

adolescents during preoperative testing appointments,

1. medications.

which may involve

2. stethoscopes.

1. explaining anesthesia and surgery in

3. anesthesia masks.

developmentally appropriate terms.

4. glass ampules.

2. providing a preoperative tour.

5. blood pressure cuffs.

3. facilitating medical play.

6. electrocardiogram (ECG) leads.

4. admitting the child to the hospital.

a. 1, 3, and 5 b. 2, 4, and 6

a. 1 and 3 b. 2 and 4

c. 2, 3, 5, and 6 d. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6

c. 1, 2, and 3 d. 1, 2, 3, and 4

5. The primary source of stress for infants and toddlers is

3. When preoperative preparation by a child life specialist a. altered body image.

cannot be provided, anesthesiologists are in the best b. fear of death.

20 j AORN Journal www.aornjournal.org

July 2016, Vol. 104, No. 1 Preoperative Care of Children

c. loss of control. 4. caregiver separation.

d. separation from caregivers. 5. loss of control.

6. fear of death.

6. When interacting with preschoolers, it is important for a. 1, 3, and 5 b. 2, 4, and 6

the perioperative nurse to understand that children in c. 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 d. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6

this age group may

1. misinterpret words that require abstract thinking. 9. When caring for children with autism spectrum

2. believe they did something wrong to deserve what disorder, the perioperative nurse should use family-

is happening to them. centered care principles, including

3. be concerned about the cosmetic implications of 1. acknowledging parents and caregivers as experts

undergoing surgery. regarding their children.

4. be more cooperative when remaining close to a 2. involving parents and caregivers in the

parent. development of an optimal care plan.

a. 1 and 3 b. 1, 2, and 4 3. speaking privately with a parent first to determine the

c. 2, 3, and 4 d. 1, 2, 3, and 4 most effective approach for the child.

7. To help the school-aged child feel more involved in a. 1 and 2 b. 1 and 3

his or her care, the perioperative nurse should c. 2 and 3 d. 1, 2, and 3

consider allowing the child to perform simple tasks

when appro-priate, such as 10. When managing the environment for a child with autism

a. removing his or her own ECG leads. spectrum disorder, the perioperative nurse should

b. scheduling a postoperative appointment. 1. speak softly and slowly.

c. changing his or her own surgical dressing. 2. avoid using the word “no.”

d. choosing when to be discharged. 3. remove unnecessary equipment from the patient’s

room.

8. Common concerns of adolescent patients include 4. keep supplies out of view until just before use.

1. altered body image. 5. turn down lights and volume of alarms.

2. peer rejection. a. 4 and 5 b. 1, 2, and 3

3. disability. c. 1, 2, 3, and 4 d. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5

www.aornjournal.org AORN Journal j 21

LEARNER EVALUATION

Continuing Education:

Preoperative Care of Children:

Strategies From a Child Life

Perspective 1.7 www.aornjournal.org/content/cme

T his evaluation is used to determine the extent to

this continuing education program met your

learning needs. The evaluation is printed

which 7. Will you be able to use the information from this

article in your work setting?

1. Yes 2. No

here for your convenience. To receive continuing education

credit, you must complete the online Examination and Learner 8. Will you change your practice as a result of reading

Evaluation at http://www.aornjournal.org/content/cme. Rate the this article? (If yes, answer question #8A. If no,

items as described below.

answer question #8B.)

8A. How will you change your practice? (Select all that apply)

OBJECTIVES 1. I will provide education to my team regarding

why change is needed.

To what extent were the following objectives of this

2. I will work with management to

continuing education program achieved?

change/implement a policy and procedure.

1. Explain the role of the child life specialist.

3. I will plan an informational meeting with physi-

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

cians to seek their input and acceptance of the

2. Discuss the role of the perioperative nurse in need for change.

decreasing preoperative parental and child anxiety. 4. I will implement change and evaluate the effect

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High of the change at regular intervals until the

change is incorporated as best practice.

3. Describe strategies for providing developmentally 5. Other: __________________________________

appropriate care to infants, children, and adolescents.

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High 8B. If you will not change your practice as a result of

reading this article, why? (Select all that apply)

4. Describe strategies for providing care to children with 1. The content of the article is not relevant to my

developmental delays. practice.

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High 2. I do not have enough time to teach others about

the purpose of the needed change.

CONTENT 3. I do not have management support to make a

change.

5. To what extent did this article increase your

4. Other: __________________________________

knowledge of the subject matter?

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

9. Our accrediting body requires that we verify the time

6. To what extent were your individual objectives met? you needed to complete the 1.7 continuing education

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High contact hour (102-minute) program: _____________

22 j AORN Journal www.aornjournal.org

Você também pode gostar

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Hospital Management SystemDocumento9 páginasHospital Management Systemdarshana gulhaneAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 815 Article Challenges of Nursing StudentsDocumento12 páginasAssignment 815 Article Challenges of Nursing StudentsabdirahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Curriculum Vitae SampleDocumento5 páginasCurriculum Vitae SampleJohn RwegasiraAinda não há avaliações

- Medical Coder / BillerDocumento1 páginaMedical Coder / Billerapi-77384278Ainda não há avaliações

- SH0102Documento12 páginasSH0102Anonymous 9eadjPSJNgAinda não há avaliações

- Trinidad Guardian - 03.01.23Documento36 páginasTrinidad Guardian - 03.01.23Ashaleah LlamsAinda não há avaliações

- National Clinical Guidelines For Stroke Fourth EditionDocumento232 páginasNational Clinical Guidelines For Stroke Fourth EditionRosa Mabel Sanchez RoncalAinda não há avaliações

- Out-Patient Department: S.Mallikarjuna MHADocumento14 páginasOut-Patient Department: S.Mallikarjuna MHAsandhyakrishnanAinda não há avaliações

- Pet CT & CK Individual SplitDocumento38 páginasPet CT & CK Individual SplitManikantaAinda não há avaliações

- Ambulatory Care 2Documento5 páginasAmbulatory Care 2api-273330093Ainda não há avaliações

- Latihan Soal UtsDocumento8 páginasLatihan Soal UtsRobi DanuartaAinda não há avaliações

- Pretty Modern by Alexander EdmondsDocumento44 páginasPretty Modern by Alexander EdmondsDuke University Press80% (5)

- Comp Health 411 MGMT CHPT 2Documento39 páginasComp Health 411 MGMT CHPT 2Liza GeorgeAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation1 ATE ARLENEDocumento61 páginasPresentation1 ATE ARLENELorraine CayamandaAinda não há avaliações

- Running Head: CASE ANALYSIS #22 1Documento11 páginasRunning Head: CASE ANALYSIS #22 1Vikram KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Your Social Security Rights in GermanyDocumento51 páginasYour Social Security Rights in GermanyKatherine TasanAinda não há avaliações

- Test Bank For Personality 10th EditionDocumento24 páginasTest Bank For Personality 10th EditionAndrewHerreraqpgz100% (42)

- Mount Sinai Expert Guides Critical Care 1St Edition Stephan A Mayer Full ChapterDocumento67 páginasMount Sinai Expert Guides Critical Care 1St Edition Stephan A Mayer Full Chaptersandra.fiorini706100% (15)

- Leprosy in Nepal - 3Documento5 páginasLeprosy in Nepal - 3Prabesh LuitelAinda não há avaliações

- The Gemini Virtual ClinicDocumento19 páginasThe Gemini Virtual ClinicKritika SoniAinda não há avaliações

- National Course Dates 2024Documento2 páginasNational Course Dates 20245gr4wvbbg5Ainda não há avaliações

- DOH HFSRB QOP 01 Form 2 3212019 postedDOHDocumento2 páginasDOH HFSRB QOP 01 Form 2 3212019 postedDOHMarcy100% (1)

- HRM2605 - Assignment 07 - 2022 - S1 (AutoRecovered)Documento4 páginasHRM2605 - Assignment 07 - 2022 - S1 (AutoRecovered)Melashini PothrajuAinda não há avaliações

- 2019-11-21 Calvert County TimesDocumento24 páginas2019-11-21 Calvert County TimesSouthern Maryland OnlineAinda não há avaliações

- Quality Assurance ProgramDocumento16 páginasQuality Assurance ProgramMyca Omega Lacsamana100% (1)

- Questions 26 - 31 Are Based On The Following PassageDocumento21 páginasQuestions 26 - 31 Are Based On The Following Passagehoneym694576Ainda não há avaliações

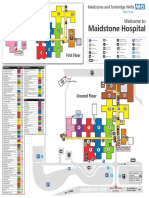

- Maidstone Hospital Internal MapDocumento1 páginaMaidstone Hospital Internal MapMwa0% (3)

- Stakeholder Engagement Plan Guide and TemplateDocumento3 páginasStakeholder Engagement Plan Guide and TemplateDan RadaAinda não há avaliações

- 000 Botswana - Landscape-Analysis - Resources-4Documento58 páginas000 Botswana - Landscape-Analysis - Resources-4Deddy DarmawanAinda não há avaliações

- Change Force Field AnalysisDocumento6 páginasChange Force Field AnalysisSolan ChalliAinda não há avaliações