Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Effect of Protruding Ears On Visual Fixation Time and Perception of Personality

Enviado por

rahulprabhakaranTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Effect of Protruding Ears On Visual Fixation Time and Perception of Personality

Enviado por

rahulprabhakaranDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Research

Original Investigation

Effect of Protruding Ears on Visual Fixation Time

and Perception of Personality

Ralph Litschel, MD; Juleke Majoor, MD; Abel-Jan Tasman, MD

Invited Commentary page 189

IMPORTANCE Protruding ears are often thought to be a stigma, supposedly drawing attention Journal Club Slides at

and negatively influencing the perception of personality. These purported negative effects jamafacialplasticsurgery.com

that may indicate corrective aesthetic otoplasty in patients too young to provide informed

CME Quiz at

consent have not been quantified.

jamanetworkcme.com and

CME Questions page 232

OBJECTIVE To quantify attention directed toward protruding ears and its effect on the

perception of selected personality traits.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS In this observational study conducted from August 1,

2013, to October 31, 2013, visual scan paths were recorded of 20 lay observers looking at

photographs of faces of 20 children (age range, 5-19 years) with either protruding ears or ears

morphed via computer software to appear nonprotruding. Subsequently, the observers rated

10 perceived personality traits based on the same photographs.

MAIN OUTCOMES MEASURES Visual fixation time on protruding vs nonprotruding ears was

compared and correlated with observers’ scores for personality traits.

RESULTS Fixation time on protruding ears was significantly longer compared with that for

morphed nonprotruding ears (mean [SD], 9.6% [5.6%] vs 5.8% [3.2%] of total fixation time,

P = .04). The difference between the overall personality questionnaire scores and between

individual scores for assiduousness, intelligence, and likeability was not significant for

protruding and nonprotruding ears. Faces in which the protruding auricles received the

highest percentage of visual attention scored higher than average for the overall personality

scores (mean [SD], 66.09 [4.50] vs. 55.81 [13.36]) and for assiduousness (6.64 [0.74] vs. 5.59

[1.41]), intelligence (6.78 [0.74] vs. 5.83 [1.31]), and likeability (7.29 [0.47] vs. 6.28 [1.40]).

Author Affiliations: Department of

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE Protruding ears had the potential to draw viewers’ attention

Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck

but did not cause a negative perception of personality traits. This study therefore does not Surgery, Cantonal Hospital, St Gallen,

provide confirmatory evidence for the stigmatizing nature of protruding ears. Switzerland.

Corresponding Author: Abel-Jan

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE 3. Tasman, MD, Department of

Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck

Surgery, Cantonal Hospital,

JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2015;17(3):183-189. doi:10.1001/jamafacial.2015.0078 Rorschacher Str 95, 9007 St Gallen,

Published online March 19, 2015. Switzerland

(abel-jan.tasman@kssg.ch).

P

rotruding ears continue to be perceived as a negative defined as “an attribute or characteristic that conveys a social

physical attribute in many cultural settings, with af- identity that is devalued in a particular social context,” which

fected children frequently being ridiculed and adoles- includes “being the target of negative stereotypes, being re-

cents experiencing reduced self-esteem.1 Protruding ears have jected socially, being discriminated against, and being eco-

been associated with inferior cognitive performance at school, nomically disadvantaged.”5(p505) Facial stigmata, such as scars,

immaturity, less favorable personality traits, diminished self- acne, strabismus, nasal deformities, and protruding ears are

confidence, and social avoidance.2,3 Media often select a per- the most common reasons for a request for surgical revision.

son with large, prominent, or oddly shaped ears when wish- Persons with these facial stigmata provoke a negative reac-

ing to depict an odd character or a less-intelligent individual. tion in the observer, with facial deformities having a negative

Few, if any, features are believed to elicit such negative re- effect on the perception of honesty, trustworthiness, and em-

sponses as prominent or overly large ears. Prominent ears have ployability and, thereby, social functionality.6 The relation-

been found to be significantly larger than normal ears.4 From ship between visual deformities and high psychological dis-

this perspective, protruding ears may be perceived as a stigma, tress was demonstrated to be close.7 Several studies have

jamafacialplasticsurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery May/June 2015 Volume 17, Number 3 183

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 09/02/2018

Research Original Investigation Protruding Ears

analyzed the psychological effect of microtia in children.8,9 Pa- reflecting the variability found in the consecutive sample.

tients with larger deformities were found to cope better with Outcome simulations were created as part of the routine ini-

the negative feelings of others (mostly pity and aversion) prob- tial consultation using Adobe Photoshop Elements (Adobe

ably owing to adaptation, unlike those with less-pronounced Systems) as described elsewhere. 17 Simulations of the

cosmetic deformities, who may be continuously uncertain intended outcome of otoplasty were used instead of the

about their ears potentially becoming subject to ridicule.10 Chil- actual postoperative outcome to eliminate inevitable con-

dren pay more attention than do adults to small differences founders in postoperative photographs, such as facial

in appearance between themselves and others.1 Measuring the expression or changed hair color, hairstyle, or clothing

effect of corrective otoplasty using tests, such as the Child Be- (Figure 1). The 20 preoperative photographs and the 20

havior Checklist, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Chil- simulated outcome photographs were divided into 2 series

dren, and the Children’s Depression Inventory, revealed im- of 20 photographs each, containing either the preoperative

provements in almost all the assessed items after the or the simulated outcome photograph. These sets were pro-

procedure.10,11 Happiness and self-confidence increased, so- cessed for eye tracking by cropping, centering, and correct-

cial experience improved, and bullying was reduced. Oto- ing scales (resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels) of the patient

plasty was also found to potentially significantly increase pa- images and by adding calibration images and relaxing photo-

tients’ health-related quality of life and lead to a high rate of graphs of pleasant landscapes between the patient photo-

patient satisfaction.12,13 It is estimated that roughly 10% of the graphs in a file (PowerPoint, Microsoft Office Professional

population bears some type of facial deformity, with protrud- 2010) for presentation. Presentation times of the faces and

ing ears having an incidence of 5%.14 Surprisingly, given the landscapes were 10 and 3 seconds, respectively.

high prevalence and psychological effect of facial deformi- Twenty participants were recruited from the outpatient

ties, data on the visual perception of faces with deformities are clinic at the Department of Otorhinolaryngology–Head and

sparse.15,16 Neck Surgery of Cantonal Hospital. Participants were pa-

To our knowledge, no attempt at quantifying the tients in good health presenting for a routine follow-up, as well

attention-drawing potential of protruding ears has been pub- as persons who were accompanying patients. All participants

lished. Also, the effect of auricular deformities on the per- (18 male and 2 female; mean age, 44.7 years [range, 21-75 years])

ception of personality traits has not been reported. The aim had normal, symmetric eye movements as a prerequisite for

of this study was therefore to quantify the visual attention of eye tracking. The participants were informed that they would

naive observers directed to protruding ears and to measure be asked questions about the personality of the persons whose

the effect of protruding ears on the perception of personality faces they were about to see on a screen after the having seen

traits. Our first hypothesis was that protruding ears unknow- the photographs. Participants provided written informed con-

ingly cause the observer to give them more visual attention sent that their eye movements would be recorded but they were

compared with nonprotruding ears; our second hypothesis not informed of the purpose of the study.

was that personality traits of faces with protruding ears are An eye tracker is a device used, especially in psychologi-

judged less favorably. cal research, to record eye movements (visual scan path) of a

study participant and measures the duration of the fixation in

specific regions of interest. This technique enables investiga-

tion of the spontaneous, initial visual assessment of a face. A

Methods visual scan path is composed of a sequence of fixations and

This observational study was conducted at the Department of saccades.12,18 Fixations contain a continuous series of gaze

Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery of Cantonal Hos- points on a segment of the visual field with a predefined du-

pital, St Gallen, Switzerland. Written informed consent for the ration that is set at 200 milliseconds.18

use of patients’ photographs was obtained from patients or The visual scan paths (Figure 2) were recorded using a To-

their legal guardians and ethical approval was granted by the bii X120 eye tracker (Tobii Technology AB) linked to a host com-

local Ethics Committee of the Canton St Gallen. The study con- puter and a second monitor with a 19-inch diagonal display fac-

sisted of 2 parts, reflecting both hypotheses. ing the seated participant. For the calibration of the eye tracker

and presentation of the photographs, Tobii Studio Software,

Visual Attention for Protruding and Nonprotruding Ears version 2.0.6 (Tobii Technology AB), was used, in which par-

In the first part, visual attention to the auricles was quanti- ticipants had to follow a red dot on the screen.

fied with an eye-tracking device. A sample of 20 preopera- In each group, there were 200 eye-tracker measurements

tive photographs of patients (14 male and 6 female; age and a total of 400 measurements. The power analysis was based

range, 5-19 years) who had requested an otoplasty and 20 on the data published by Ishii et al14 (mean [SD] fixation time

photographs of the simulated desired outcome of the proce- of the defect region of 1630 [1177] milliseconds). A total of 137

dure was selected from the database of the Department of viewed photographs per group or 247 photographs in total were

Otorhinolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery of Cantonal required to detect a difference of 400 milliseconds with 80%

Hospital. All en face patient photographs were taken under power and a significance level of P < .05. These calculated num-

standardized conditions (distance, lighting, background, and bers of photographs were increased from 137 and 247 to 200

resolution). The degree of overall ear protrusion and sym- and 400, respectively, to improve power of the study and be-

metry of protrusion was heterogeneous among the patients, cause of anticipated withdrawals.

184 JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery May/June 2015 Volume 17, Number 3 (Reprinted) jamafacialplasticsurgery.com

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 09/02/2018

Protruding Ears Original Investigation Research

Figure 1. Preoperative and Simulated Postoperative Photographs of Patients With Protruding Ears

A B

C D

E F

A-F, Selection of the photographs of

6 of 20 patients who were included

in the study. The preoperative images

are on the left, the simulated

intended outcome of an otoplasty on

the right. These are the patients who

are referred to in Figure 5,

representing the orange, green, and

blue squares.

Personality Ratings for Faces With Protruding fixation time of both pinnae was also correlated with the sum

and Nonprotruding Ears score of the questionnaire, as well as with the scores for indi-

For the assessment of perceived personality traits, a question- vidual questions regarding likeability, intelligence, and as-

naire was delivered that included pairs of antipodes on 10 per- siduousness.

sonality traits (sociable–withdrawn, content–discontent, as-

siduous–lazy, intelligent–unintelligent, creative–uninspired,

friendly–unfriendly, successful–unsuccessful, exciting–

boring, accessible–inaccessible, and honest–dishonest). These

Results

items were extracted from the Neuroticism-Extraversion- Visual Attention for Protruding

Openness Personality Inventory and are said to represent the and Nonprotruding Ears

5 broad dimensions of traits that are used to describe human Data of all 20 observers on 20 patient photographs were ame-

personality: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeable- nable for analysis of 400 eye-tracking data sets. Four ques-

ness, and conscientiousness.19 We added 4 more traits in ac- tionnaires had to be excluded owing to missing data.

cordance with previously published research: successful- Mean (SD) fixation time of both auricles was 9.6% (5.6%)

ness, boringness, accessibility, and honesty.20 Each trait was of total fixation time for protruding ears and 5.8% (3.2%) for

displayed on a visual analog scale from 0 to 10, with 0 indi- nonprotruding ears (Figure 4). This difference was signifi-

cating the lowest and 10 the highest positive score. These per- cant (P = .04).

sonality traits were rated by all participants immediately af-

ter they had completed the eye-tracking part of the study with Personality Ratings for Faces With Protruding

the image they had seen on the screen printed on the ques- and Nonprotruding Ears

tionnaire for recognition. Eye tracking and rating of person- Sixteen of the 20 observers returned the questionnaire fully

ality traits required between 25 and 35 minutes and was moni- completed, including 10 visual analog score personality trait

tored by one of us (J.M.). ratings for each patient image, totaling 200 individual rat-

ings by each of the 16 observers, for a sum of 3200 individual

Statistical Analysis ratings.

The auricles were selected as the area of interest in Tobii Stu- A significant correlation between the sum of the person-

dio and the fixation time of both pinnae was calculated as the ality questionnaire scores for faces with protruding and non-

percentage of total fixation time (Figure 3). The difference be- protruding ears was found (Pearson correlation; R, 0.73,

tween relative fixation times for protruding and nonprotrud- P < .001). The difference between the sum of the personality

ing ears was analyzed by the average fixation time for each questionnaire scores for faces with protruding and nonpro-

patient with protruding and nonprotruding ears with a non- truding ears was not significant (mean [SD], 55.8 [1.37] vs 53.6

parametric paired sample test (Wilcoxon signed rank test). The [1.25], P = .31).

jamafacialplasticsurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery May/June 2015 Volume 17, Number 3 185

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 09/02/2018

Research Original Investigation Protruding Ears

Figure 2. Eye-Tracker Recordings

A B

C D

A and B, The upper row shows

preoperative photographs. C and D,

The lower row shows simulated

postoperative photographs. Each dot

represents a fixation time of more

than 200 milliseconds; dot size

corresponds to visual fixation time.

Connecting lines represent the visual

scan path. Fixation times are

represented as heat maps (red

represents maximum cumulative

fixation time).

As for the sum of all personality traits, the difference be-

tween the mean (SD) scores for assiduousness, intelligence, and Discussion

likeability did not differ significantly depending on protru-

sion or deformity of the ears (5.59 [14.5] vs 5.24 [1.43], P = .22; Facial stigmata catch the eye because a negative stimulus re-

5.83 [1.34] vs 5.53 [1.42], P = .41; and 6.28 [1.44] vs 6.20 [1.26], ceives more visual attention than does a positive stimulus. Spi-

P = .83, respectively). A significant positive correlation be- ders or unhappy faces, for example, are fixated on longer than

tween the scores for faces with protruding and nonprotrud- butterflies or happy faces.21-23 One contributing factor to this

ing ears was found for likeability (R, 0.75, P < .001). phenomenon may be that an abnormality in the face is per-

Both the quartile of the 5 faces for which the protruding ceived as new and represents a novel stimulus. According to

auricles received most visual attention (patients 2, 3, 4, 5, and the novel stimulus theory, to become familiar with it, people

6, respectively; orange and green squares in Figure 5) and the stare at a stigma.24 Also, unexpected facial features, such as a

quartile of the 5 faces with the largest difference in fixation time crooked nose or floppy ears, may be helpful in the face recog-

between protruding and nonprotruding auricles (patients 1, 3, nition process and therefore receive more attention.7,25

4, 5, and 6, respectively; orange and blue squares in Figure 5) Research has shown a negative correlation between at-

scored higher than the average for overall personality scores tractiveness and the lesion size of a facial disfigurement but

(mean [SD], 66.09 [4.50] vs 55.81 [13.36]) and for individual not between attractiveness and the location of a facial

scores on assiduousness (6.64 [0.74] vs 5.59 [1.41]), likeability disfigurement.26 A person’s attractiveness is known to strongly

(7.29 [0.47] vs 6.28 [1.40]), and intelligence (6.78 [0.74] vs 5.83 influence the perception of personality by the viewer. This phe-

[1.31]). In the quartile of faces for which the protruding au- nomenon is often referred to as the attractiveness halo. Indi-

ricles received most visual attention, the sum of personality viduals who are considered attractive will more likely be seen

scores and the likeability score was lower for the modified pho- as nice, friendly, and intelligent. As a consequence of a nega-

tograph without protrusion of the auricle in 4 of 5 patients (pa- tive first impression, people with facial deformities will more

tients 3, 4, 5, and 6). The scores for assiduousness and intel- likely be treated harshly.27 Such a first impression can have a

ligence were lower for the modified images in 3 of 5 patients distressing effect and dramatic psychosocial influence on

(patients 3, 4, and 5). people with facial disfigurements. Dating agents ranked pro-

186 JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery May/June 2015 Volume 17, Number 3 (Reprinted) jamafacialplasticsurgery.com

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 09/02/2018

Protruding Ears Original Investigation Research

Figure 3. Marking the Area of Interest (AOI) for Both Ears Figure 4. Visual Fixation Time for Both Ears for Protruding

vs Nonprotruding Ears

30

Nonprotruding Ears, %

20

10

AQI-R-EAR 0

AQI-L-EAR

0 10 20 30

Protruding Ears, %

Visual fixation time is reported as a percentage of total fixation time.

Figure 5. Visual Fixation Time of Both Ears vs Personality Trait Total Score

A B

The right and left ear were individually marked on the patient photographs 80 80

using the eye tracker’s Tobii Studio Software. Personality Sum Score

Personality Sum Score

60 60

truding ears as having a large negative effect more in men than

in women.28 Of all visible disfigurements, those of the face

40 40

seem to be least tolerated and most likely to provoke anxiety

and aversion. Children with protruding ears had more prob-

20 20

lems regarding self-esteem compared with children with nor-

mal ears or even facial port-wine stains.29

Experience shows that the eyes of the viewer typically fol- 0 0

0 10 20 30 0 10 20 30

low a particular scan path in a face with no obvious facial de- Protruding Ears, % Nonprotruding Ears, %

formities, focusing on a central triangle, which includes the

mouth, nose, and eyes.14,30-32 Attention had been found to be A, Protruding ears. B, Nonprotruding ears. Visual fixation time is reported as a

redirected to obvious facial defects at the expense of time spent percentage of total fixation time. Four orange squares and 1 green square

represent the patient quartile with the longest fixation time on both ears. Orange

analyzing the central triangle.

squares and the blue square represent the patient quartile with the largest

Therefore, it was expected that the average visual fixa- differences between the fixation times of protruding and nonprotruding ears.

tion time on protruding ears would be longer than the atten-

tion directed to nonprotruding ears. Still, the difference that

was quantified in this study appeared smaller than the per-

ception of the clinical problem from the patient’s and physi- most attention scoring higher than the 3 quartiles with less no-

cian’s perspective might suggest. The experimental setup and ticeable ears. These faces also yielded higher scores than their

the cutoff setting for registration of visual fixation of 200 mil- counterpart with corrected auricles in 4 of 5 cases for the total

liseconds may have reduced an effect that could be more pro- personality sum score and likeability score and in 3 of 5 cases

nounced in personal encounters. The spectrum of auricular de- for assiduousness and intelligence scores. In light of these find-

formities included in this study was representative of the ings, the relevance of protruding ears as a negative stigma re-

patients requesting an otoplasty at a Swiss tertiary care cen- garding perceived personality traits may be considered less pro-

ter. Obviously, the degree of deformity varied considerably, ex- nounced than purported in the literature.

plaining part of the variation in attention directed toward the This study has several strengths. Use of preoperative origi-

ears. Only ears that protruded markedly or were conspicu- nal and morphed postoperative images in which the degree of

ously deformed caught the eye, as documented for patients protrusion and deformity was the only variable in otherwise

2, 3, 4, 5, and 6. identical images excluded potentially attention-drawing dif-

If noticeable protruding ears were to be perceived by the ferences between preoperative and real postoperative photo-

population at large as heralding less-favorable personality traits, graphs. In addition, lay individuals acting as observers in this

the experimental setup in this study should be expected to have study were naive to the objective of the study and were shown

reflected this phenomenon, at least in part, through lower either the original or the morphed image, excluding a poten-

scores given by the observers. Surprisingly, the opposite was tial recognition of faces or noticing of a difference between 2

found, with the quartile of faces with the ears attracting the versions of the same face as a confounder. Finally, the degree

jamafacialplasticsurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery May/June 2015 Volume 17, Number 3 187

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 09/02/2018

Research Original Investigation Protruding Ears

of protrusion was variable, further reducing the clues the ob- sibility, respecting the expected attention span of partici-

servers may have noticed regarding the end point of the study pants. The definition of 10 seconds’ projection time for each

while scanning the faces. face was arbitrary and an effect of this projection time cannot

Several limitations of this study require discussion. First, be ruled out. Finally, answering 20 sets of 10 questions each

observers who were initially naive regarding the end point of on personality was thought to be tedious by some partici-

the study may have noticed the high prevalence of protrud- pants and fatigue cannot be ruled out as a potential con-

ing ears (50%) while viewing the faces, which may explain founder. Still, with the sequence of the original or modified

relative fixation times that may exceed those reported in the patient image being identical in both sets, the effect of

literature. Reducing the likelihood of this confounder would fatigue should be expected to have been minor and evenly

have required a substantially larger sample of faces with distributed. Finally, the group of lay observers may be con-

inconspicuous ears. A preliminary study had revealed that a sidered to be representative of the Swiss adult population.

substantially larger sample would have strained the visual Still, the effect of a cultural bias on the perception of protrud-

attention span of observers to the point of acquiring invalid ing ears cannot be ruled out.

data. It also remains unclear to what extent looking at photo-

graphs of faces on a monitor relates to visual analysis of a

face during encounters in person. The faces included dis-

played a variable degree of protrusion or deformation of the

Conclusions

auricle, reflecting the deformities found in a consecutive To our knowledge, this is the first study quantifying the at-

sample of patients who requested an otoplasty in a Swiss ter- tention-drawing potential of protruding ears using an eye-

tiary care center. The simulated degree of correction was tracking device and the first report correlating this effect with

variable, mirroring the preoperatively agreed-upon objective perceived personality. The confirmation of the hypothesis that

of a planned otoplasty. The shape of the modified auricle was protruding ears catch the attention of observers was ex-

realistic as to the desired projection but less so for the antici- pected. Not finding support for the second hypothesis, that pro-

pated relative position of the antihelical fold and helix in truding ears negatively affect the perception of personality

some patients. This shortcoming being inherent to the traits, was surprising. It remains unclear to what extent local

imaging method used in this study may have had an effect on cultural factors may have influenced this outcome. These data

the fixation times of virtually corrected pinnae. Also, the eye- may be helpful for future reference and for comparison with

tracking segment of the study was designed for optimum fea- studies addressing other facial regions of interest.

ARTICLE INFORMATION 4. Driessen JP, Borgstein JA, Vuyk HD. Defining the 13. Hao W, Chorney JM, Bezuhly M, Wilson K,

Accepted for Publication: December 9, 2014. protruding ear. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22(6): Hong P. Analysis of health-related quality-of-life

2102-2108. outcomes and their predictive factors in pediatric

Published Online: March 19, 2015. patients who undergo otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg.

doi:10.1001/jamafacial.2015.0078. 5. Crocker JMB, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert

DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, eds. The Handbook of Social 2013;132(5):811e-817e.

Author Contributions: Dr Tasman had full access Psychology. Vol 2. 4th ed. Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill; 14. Ishii L, Carey J, Byrne P, Zee DS, Ishii M.

to all the data in the study and takes responsibility 1998. Measuring attentional bias to peripheral facial

for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the deformities. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(3):459-465.

data analysis. 6. Rankin M, Borah GL. Perceived functional

Study concept and design: Litschel, Tasman. impact of abnormal facial appearance. Plast 15. Valente SM. Visual disfigurement and

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(7):2140-2146. depression. Plast Surg Nurs. 2009;29(1):10-18.

authors. 7. Madera JM, Hebl MR. Discrimination against 16. McNeil ML, Aiken SJ, Bance M, Leadbetter JR,

Drafting of the manuscript: Litschel, Tasman. facially stigmatized applicants in interviews: an Hong P. Can otoplasty impact hearing? a

Critical revision of the manuscript for important eye-tracking and face-to-face investigation. J Appl prospective randomized controlled study

intellectual content: All authors. Psychol. 2012;97(2):317-330. examining the effects of pinna position on speech

Statistical analysis: Litschel, Tasman. 8. Okajima H, Suzuki K, Takeichi Y, Umeda K, reception and intelligibility. J Otolaryngol Head

Administrative, technical, or material support: All Baba S. Long-term results of otoplasty for microtia. Neck Surg. 2013;42:10.

authors. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1996;525:25-29. 17. Palma P, Khodaei I, Tasman AJ. A guide to the

Study supervision: Litschel, Tasman. assessment and analysis of the rhinoplasty patient.

9. Steffen A, Meyer Zu Natrup C, König IR,

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. Frenzel H, Rotter N. Analysis of psychosocial Facial Plast Surg. 2011;27(2):146-159.

changes following ear reconstruction with rib 18. Toh WL, Rossell SL, Castle DJ. Current visual

REFERENCES cartilage—development of a short test [in German]. scanpath research: a review of investigations into

1. Ju DM. The psychological effect of protruding Laryngorhinootologie. 2009;88(4):247-252. the psychotic, anxiety, and mood disorders. Compr

ears. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1963;31:424-427. 10. Cooper-Hobson G, Jaffe W. The benefits of Psychiatry. 2011;52(6):567-579.

2. Braun T, Hainzinger T, Stelter K, Krause E, otoplasty for children: further evidence to satisfy 19. McCrae RR, John OP. An introduction to the

Berghaus A, Hempel JM. Health-related quality of the modern NHS. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. five-factor model and its applications. J Pers. 1992;

life, patient benefit, and clinical outcome after 2009;62(2):190-194. 60(2):175-215.

otoplasty using suture techniques in 62 children 11. Gasques JA, Pereira de Godoy JM, Cruz EM. 20. Gruendl M. Beautycheck: causes and

and adults. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(6): Psychosocial effects of otoplasty in children with consequences of human facial attractiveness.

2115-2124. prominent ears. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32(6): http://www.uni-regensburg.de/Fakultaeten/phil

3. Arnulf W. Personalauswahl: Anforderungsprofil, 910-914. _Fak_II/Psychologie/Psy_II/beautycheck/english

Bewerbersuche, Vorauswahl und 12. Noton D, Stark L. Eye movements and visual /zusammen/zusammen1.htm. Updated July 2011.

Vorstellungsgespräch. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer perception. Sci Am. 1971;224(6):35-43. Accessed August 1, 2014.

Gabler; 2008.

188 JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery May/June 2015 Volume 17, Number 3 (Reprinted) jamafacialplasticsurgery.com

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 09/02/2018

Protruding Ears Original Investigation Research

21. Fox E, Russo R, Bowles R, Dutton K. Do 25. Tsao DY, Schweers N, Moeller S, Freiwald WA. stains and prominent ears. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

threatening stimuli draw or hold visual attention in Patches of face-selective cortex in the macaque Psychiatry. 1995;34(12):1637-1647.

subclinical anxiety? J Exp Psychol Gen. 2001;130(4): frontal lobe. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11(8):877-879. 30. Walker-Smith GJ, Gale AG, Findlay JM. Eye

681-700. 26. Godoy A, Ishii M, Byrne PJ, Boahene KD, movement strategies involved in face perception.

22. Rinck M, Becker ES. Spider fearful individuals Encarnacion CO, Ishii LE. The straight truth: Perception. 1977;6(3):313-326.

attend to threat, then quickly avoid it: evidence measuring observer attention to the crooked nose. 31. Phillips ML, David AS. Visual scan paths are

from eye movements. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115 Laryngoscope. 2011;121(5):937-941. abnormal in deluded schizophrenics.

(2):231-238. 27. Pertschuk MJ, Whitaker LA. Social and Neuropsychologia. 1997;35(1):99-105.

23. Mogg K, Millar N, Bradley BP. Biases in eye psychological effects of craniofacial deformity and 32. Groner R, Groner MT. Attention and eye

movements to threatening facial expressions in surgical reconstruction. Clin Plast Surg. 1982;9(3): movement control: an overview. Eur Arch

generalized anxiety disorder and depressive 297-306. Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 1989;239(1):9-16.

disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109(4):695-704. 28. Mojon-Azzi SM, Potnik W, Mojon DS. Opinions

24. Langer EL, Fiske S, Taylor SE, Chanowitz B. of dating agents about strabismic subjects’ ability to

Stigma, staring, and discomfort: a novel-stimulus find a partner. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(6):765-769.

hypothesis. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1976;12(5):451-463. 29. Sheerin D, MacLeod M, Kusumakar V.

doi:10.1016/0022-1031(76)90077-9. Psychosocial adjustment in children with port-wine

Invited Commentary

Moving Toward Objective Measurement of Facial Deformities

Exploring a Third Domain of Social Perception

Lisa E. Ishii, MD, MHS

In this issue, Litschel et al1 present novel data on the visual dis- Significant progress has been made in recent years in sub-

traction caused by protruding ears. They used an eye- jectively and/or objectively measuring the perception of the

tracking device for objective evaluation and correlated the eye- casual observer of facial deformities or abnormalities, includ-

tracking test findings with personality survey assessments. ing the “abnormality” of the aging face. In a 2013 survey study

These data represent an im- by Zimm et al,3 patients who had undergone surgical proce-

portant addition to a burgeon- dures for aging faces were perceived to be younger than their

Related article page 183 ing body of evidence on the actual age. An objective line of investigation using eye track-

effect of facial deformities. ing has developed based on the foundation of normal face view-

Until now, in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery, we have ing, first described by Walker-Smith et al4 in the 1970s. Eye

had a relatively limited understanding of the effect of facial movements are a surrogate for attention, so, by measuring eye

deformities and abnormalities on visual distraction and fa- movements, one has insight into where an observer is direct-

cial perception. Previously, we had accepted the general te- ing attention. In their seminal work, Walker-Smith et al dem-

net that faces with abnormalities are less attractive and less onstrated that casual observers gazing on novel faces do so in

“normal,” and that our surgical procedures restore attractive- a highly conserved manner, directing the majority of atten-

ness and normality; however, these ideas have been based on tion to the central triangle region in a manner measurable using

limited objective evidence. Furthermore, we have relied pri- objective eye tracking. Recent research has taken advantage

marily on the subjective perceptions of experts and the pa- of this foundation, using eye tracking to objectively measure

tients themselves to inform our ideas on these paradigms of how distracting facial deformities are by measuring how fa-

attractiveness and normalcy, inadequately assessing the per- cial gaze patterns deviate from the normal, highly conserved

ceptions of casual observers. pattern in the presence of deformities. This method has been

Only recently have we begun to formally attempt to measure used to quantify the visual distraction caused by crooked

the effect of facial deformities from the perspective of casual ob- noses,5 skin lesions, and facial paralysis.6 After objectively

servers. The importance of measuring this effect lies in part in showing the extent to which the gaze of naive observers is

the fact that, for many people, one of their greatest concerns is drawn to facial deformities, survey studies have demon-

how they think others, particularly strangers, are viewing them. strated how observers then perceive attractiveness,7 affect

In a survey of patients with head and neck cancer, patients noted display,8 and willingness to engage in conversation, based on

that of greatest concern to them was how they would be per- the distraction of the deformity. Furthermore, these findings

ceived by others once they had a deformity.2 Patients with new have been extended to show the effect of surgical reconstruc-

facial deformities or abnormalities report changing their social tion on these visual distractions and changes in perception.6

habits to avoid encountering strangers or even family and friends. In their novel application, Litschel et al1 first measure how

Furthermore, we facial plastic and reconstructive surgeons per- casual observers gaze on faces of children with protruding ears,

form cosmetic and reconstructive procedures intrinsically be- and then measure gaze patterns after a surgical simulation,

lieving, along with the patients, that our procedure will restore using software to morph protruding ears into normal-

a more attractive and normal appearance to our patients so they appearing ears. They correlate the changes in eye gaze by an

can engage more effectively in society. observer with changes in perception of the faces before and

jamafacialplasticsurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery May/June 2015 Volume 17, Number 3 189

Copyright 2015 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 09/02/2018

Você também pode gostar

- GD&T WikipediaDocumento4 páginasGD&T WikipediaJayesh PatilAinda não há avaliações

- 082606-349Documento7 páginas082606-349Maria Lozano Figueroa 5to secAinda não há avaliações

- Ceklis Manajemen LukaDocumento5 páginasCeklis Manajemen LukaGladys OliviaAinda não há avaliações

- Radboud Repository PDF on Smile Attractiveness and PersonalityDocumento8 páginasRadboud Repository PDF on Smile Attractiveness and PersonalityRaul GhiurcaAinda não há avaliações

- Kim 2017Documento7 páginasKim 2017Erik BrooksAinda não há avaliações

- Whispered Voice Test For Screening For Hearing ImpDocumento6 páginasWhispered Voice Test For Screening For Hearing ImpNi Nengah BagiastriniAinda não há avaliações

- Treatment of Prominent Ears and Otoplasty 2015 DBDocumento6 páginasTreatment of Prominent Ears and Otoplasty 2015 DBcirugia plastica uisAinda não há avaliações

- Pone 0245557Documento17 páginasPone 0245557Juan Jose Perico GomezAinda não há avaliações

- Analise Dinamica Sorriso - Mudanças Com A IdadeDocumento2 páginasAnalise Dinamica Sorriso - Mudanças Com A IdadeCatia Sofia A PAinda não há avaliações

- Surface-Specific Correlation Between Extrinsic Stains and Early Childhood CariesDocumento46 páginasSurface-Specific Correlation Between Extrinsic Stains and Early Childhood Cariessumit kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Gates2005 PDFDocumento10 páginasGates2005 PDFsiti afifahAinda não há avaliações

- Cheloscopy-A Unique Forensic Tool PDFDocumento4 páginasCheloscopy-A Unique Forensic Tool PDFJose Li ToAinda não há avaliações

- Self-Perception of The Facial Profile An Aid in TRDocumento7 páginasSelf-Perception of The Facial Profile An Aid in TRmehdi chahrourAinda não há avaliações

- Earlier Identification of Children With Autism SpeDocumento6 páginasEarlier Identification of Children With Autism SpeIva AleksandrovaAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Measurement of Maximum Mouth Opening in Children of Kolkata and Its Relation With Different Facial TypesDocumento5 páginasClinical Measurement of Maximum Mouth Opening in Children of Kolkata and Its Relation With Different Facial TypesMarco CarranzaAinda não há avaliações

- J Ijom 2020 06 020-2Documento6 páginasJ Ijom 2020 06 020-2quajeutterugrau-6658Ainda não há avaliações

- Ali, Saad, Kamel - 2019 - Childhood-Onset Fluency Disorder (Stuttering) An Interruption in The Flow of SpeakingDocumento3 páginasAli, Saad, Kamel - 2019 - Childhood-Onset Fluency Disorder (Stuttering) An Interruption in The Flow of Speakingallson 25Ainda não há avaliações

- Surgical OrthodonticsDocumento301 páginasSurgical Orthodonticsdr_nilofervevai2360100% (4)

- Analysis of Select Facial and Dental Esthetic ParametersDocumento7 páginasAnalysis of Select Facial and Dental Esthetic ParametersJhon CarlosAinda não há avaliações

- Signs and Symptoms of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders Related To The Degree of Mouth Opening and Hearing LossDocumento9 páginasSigns and Symptoms of Temporomandibular Joint Disorders Related To The Degree of Mouth Opening and Hearing LossFelipeSanzAinda não há avaliações

- Gordon 2015Documento15 páginasGordon 2015María Victoria Hernández de la FuenteAinda não há avaliações

- Hearing Impairment and Cognitive Energy: The Framework For Understanding Effortful Listening (FUEL)Documento24 páginasHearing Impairment and Cognitive Energy: The Framework For Understanding Effortful Listening (FUEL)itskendall jAinda não há avaliações

- Volume 138, Number 4 - LettersDocumento2 páginasVolume 138, Number 4 - LettersMaybelineAinda não há avaliações

- Systematic Review of Tracking Studies in Children With Autism PDFDocumento24 páginasSystematic Review of Tracking Studies in Children With Autism PDFMH AmoueiAinda não há avaliações

- Psychological IntrusionDocumento19 páginasPsychological IntrusionMaría Daniela Rivera ElorzaAinda não há avaliações

- Feeling Normal? Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients With A Cleft Lip - Palate After Rhinoplasty With The Derriford Appearance Scale (DAS-59)Documento6 páginasFeeling Normal? Long-Term Follow-Up of Patients With A Cleft Lip - Palate After Rhinoplasty With The Derriford Appearance Scale (DAS-59)Claudia TacuriAinda não há avaliações

- Assessing Facial Asymmetry in ChildrenDocumento6 páginasAssessing Facial Asymmetry in ChildrenCatherine NocuaAinda não há avaliações

- Vallittu PK - J Dent - 1996Documento4 páginasVallittu PK - J Dent - 1996Alfredo PortocarreroAinda não há avaliações

- Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2006 Tager Flusberg 175 82Documento8 páginasSoc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2006 Tager Flusberg 175 82Victória NamurAinda não há avaliações

- Lectura Previa1-U1-M3-T1-Examining The Head and NeckDocumento12 páginasLectura Previa1-U1-M3-T1-Examining The Head and NeckCami AguilarAinda não há avaliações

- Frequently Asked Questions On DMITDocumento1 páginaFrequently Asked Questions On DMITnitinmisra77Ainda não há avaliações

- The contributions of craniofacial growth to clinical orthodonticsDocumento3 páginasThe contributions of craniofacial growth to clinical orthodonticsLibia Adriana Montero HincapieAinda não há avaliações

- Spontaneous SmileDocumento8 páginasSpontaneous SmileValery V JaureguiAinda não há avaliações

- Analisis Faciales PDFDocumento8 páginasAnalisis Faciales PDFJhon CarlosAinda não há avaliações

- Developmental Psychobiology - 2009 - Domellöf - Atypical Functional Lateralization in Children With Fetal Alcohol SyndromeDocumento10 páginasDevelopmental Psychobiology - 2009 - Domellöf - Atypical Functional Lateralization in Children With Fetal Alcohol SyndromenereaalbangilAinda não há avaliações

- Face Perception Research PaperDocumento5 páginasFace Perception Research Paperfvgh9ept100% (1)

- Negative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss reviewDocumento5 páginasNegative consequences of uncorrected hearing loss reviewGOLD WMXVAinda não há avaliações

- Hartmann 2004Documento7 páginasHartmann 2004ramiro alejandro torres velezAinda não há avaliações

- Goldenhar Syndrome: Current Perspectives: Katarzyna Bogusiak, Aleksandra Puch, Piotr ArkuszewskiDocumento11 páginasGoldenhar Syndrome: Current Perspectives: Katarzyna Bogusiak, Aleksandra Puch, Piotr ArkuszewskiDIANA PAOLA FONTECHA GONZÁLEZAinda não há avaliações

- Ear PrintDocumento33 páginasEar PrintSeema Kotalwar100% (11)

- Digital Smile Design Concept PDFDocumento18 páginasDigital Smile Design Concept PDFAndyRamosLopezAinda não há avaliações

- TMD Pediatric DentClinN Am JAH 2012Documento31 páginasTMD Pediatric DentClinN Am JAH 2012Chaithra ShreeAinda não há avaliações

- Conginitive and Dental Fear and AnxietyDocumento4 páginasConginitive and Dental Fear and Anxietyaishwarya agarwalAinda não há avaliações

- Double Dissociations in Developmental DiDocumento4 páginasDouble Dissociations in Developmental DiSahira Rivera DroguettAinda não há avaliações

- krouse-et-al-2017-plain-language-summary-earwax-(cerumen-impaction)Documento8 páginaskrouse-et-al-2017-plain-language-summary-earwax-(cerumen-impaction)sainath.vidya0309Ainda não há avaliações

- Dental Fear/anxiety Among Children and Adolescents. A Systematic ReviewDocumento10 páginasDental Fear/anxiety Among Children and Adolescents. A Systematic ReviewfghdhmdkhAinda não há avaliações

- San Ma&no,: John Frush, and Roland FisherDocumento11 páginasSan Ma&no,: John Frush, and Roland FisherAbhishek SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- The Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI) : A Practical Test For Cross-Cultural Epidemiological Studies of DementiaDocumento15 páginasThe Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI) : A Practical Test For Cross-Cultural Epidemiological Studies of DementiaZaira TejadaAinda não há avaliações

- AJODO-2013 Lin 143 6 819Documento9 páginasAJODO-2013 Lin 143 6 819player osamaAinda não há avaliações

- Forensic Odontology in Pediatric Dentistry: A. Dental IdentificationDocumento4 páginasForensic Odontology in Pediatric Dentistry: A. Dental IdentificationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- Single_dissociations_are_the_bread_and_bDocumento3 páginasSingle_dissociations_are_the_bread_and_bSahira RiveraAinda não há avaliações

- Face Blindness - ProsopagnosiaDocumento3 páginasFace Blindness - ProsopagnosiaHonoratus Irpan SinuratAinda não há avaliações

- JCDP 20 309Documento7 páginasJCDP 20 309SUMEET SODHIAinda não há avaliações

- Ventromedial frontal lobe damage affects interpretation, not exploration, of emotional facial expressionsDocumento17 páginasVentromedial frontal lobe damage affects interpretation, not exploration, of emotional facial expressionsÁLVARO RUIZ GARCÍAAinda não há avaliações

- ASSADDocumento11 páginasASSADvane dzAinda não há avaliações

- This Content Downloaded From 94.21.23.103 On Fri, 19 Mar 2021 08:12:52 UTCDocumento5 páginasThis Content Downloaded From 94.21.23.103 On Fri, 19 Mar 2021 08:12:52 UTCBorostyánLéhnerAinda não há avaliações

- Complexity: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of The Experiences of Mothers of Deaf Children With Cochlear Implants and AutismDocumento12 páginasComplexity: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of The Experiences of Mothers of Deaf Children With Cochlear Implants and AutismPablo VasquezAinda não há avaliações

- Mds Oral Pathology Thesis TopicsDocumento7 páginasMds Oral Pathology Thesis Topicsafkodkedr100% (2)

- Internacional Dentistry 2009Documento8 páginasInternacional Dentistry 2009Sung Soon ChangAinda não há avaliações

- Comparing The Perception of Dentists and Lay People To Altered Dental EstheticsDocumento14 páginasComparing The Perception of Dentists and Lay People To Altered Dental EstheticsDaniel AtiehAinda não há avaliações

- Staying in The Netherlands After Your Studies 20110624Documento5 páginasStaying in The Netherlands After Your Studies 20110624Akshay VaidhyAinda não há avaliações

- Track 4 Aerospace Structures and Materials enDocumento72 páginasTrack 4 Aerospace Structures and Materials enrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Master Mot 2015 enDocumento70 páginasMaster Mot 2015 enrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Sim1 Ap3 2Documento1 páginaSim1 Ap3 2rahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- AES-RE Specialisation Geotechnical and Environmental Engineering (RE-EGEC) enDocumento17 páginasAES-RE Specialisation Geotechnical and Environmental Engineering (RE-EGEC) enrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Academic Calender 2015-2016Documento1 páginaAcademic Calender 2015-2016Gerry AnastasatosAinda não há avaliações

- AES-GE Track Geo-Engineering (GE) enDocumento38 páginasAES-GE Track Geo-Engineering (GE) enrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- AES-AG Track Applied Geophysics (AG) enDocumento30 páginasAES-AG Track Applied Geophysics (AG) enrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- FracPaQ2D roseangleEqAreaDocumento1 páginaFracPaQ2D roseangleEqArearahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- AES-RE Specialisation Mining Engineering (RE-EMC) enDocumento14 páginasAES-RE Specialisation Mining Engineering (RE-EMC) enrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- TU DELFT Academic Calendar 2014/2015Documento1 páginaTU DELFT Academic Calendar 2014/2015rahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Aes Master 2014 enDocumento192 páginasAes Master 2014 enrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

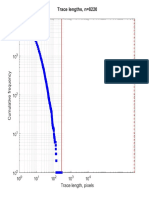

- FracPaQ2D LoglogplottracelengthDocumento1 páginaFracPaQ2D LoglogplottracelengthrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

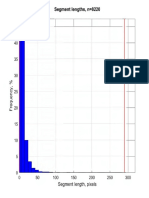

- FracPaQ2D HistosegmentlengthDocumento1 páginaFracPaQ2D HistosegmentlengthrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- FracPaQ2D HistotracelengthDocumento1 páginaFracPaQ2D HistotracelengthrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- FracPaQ2D LoglogplotsegmentlengthDocumento1 páginaFracPaQ2D LoglogplotsegmentlengthrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Admision Research Proposal TemplateDocumento4 páginasAdmision Research Proposal TemplaterahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- FracPaQ2D CracktensorDocumento1 páginaFracPaQ2D CracktensorrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Symbol Codes - ALT Codes For WindowsDocumento7 páginasSymbol Codes - ALT Codes For WindowsrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- InterPore2018 New Orleans (14-17 May 2018)Documento202 páginasInterPore2018 New Orleans (14-17 May 2018)rahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Ace18 Call For Abstracts BrochureDocumento4 páginasAce18 Call For Abstracts BrochurerahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- ONGC RecruitmentDocumento3 páginasONGC RecruitmentSreedhar Rakesh VellankiAinda não há avaliações

- AES Track Petroleum Engineering & Geosciences (PE&G) enDocumento41 páginasAES Track Petroleum Engineering & Geosciences (PE&G) enrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Jaarindeling TU Delft 2017-2018 ENGDocumento1 páginaJaarindeling TU Delft 2017-2018 ENGAdrian LokeAinda não há avaliações

- TU Delft Academic Calendar 2014/2015Documento1 páginaTU Delft Academic Calendar 2014/2015rahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Application Form: International Master Fluids Engineering For Industrial ProcessesDocumento2 páginasApplication Form: International Master Fluids Engineering For Industrial ProcessesrahulprabhakaranAinda não há avaliações

- Offshore Duty LeaveDocumento2 páginasOffshore Duty Leaverahulprabhakaran100% (1)

- Hamiltonian GraphsDocumento22 páginasHamiltonian GraphsRahul MauryaAinda não há avaliações

- Uml 3 PGDocumento114 páginasUml 3 PGGurwinder SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Oa-Kdp-Module 1Documento4 páginasOa-Kdp-Module 1Ryan AmaroAinda não há avaliações

- Asja Boys College, Charlieville: Use Electrical/Electronic Measuring DevicesDocumento2 páginasAsja Boys College, Charlieville: Use Electrical/Electronic Measuring DevicesZaid AliAinda não há avaliações

- TeamForge 620 User GuideDocumento336 páginasTeamForge 620 User GuidegiorgioviAinda não há avaliações

- STM32F103R6Documento90 páginasSTM32F103R6王米特Ainda não há avaliações

- Filezilla FTP Server Installation For Windows™ OsDocumento11 páginasFilezilla FTP Server Installation For Windows™ OsSatish ChaudharyAinda não há avaliações

- Governance model for Project XXXXDocumento7 páginasGovernance model for Project XXXXpiero_zidaneAinda não há avaliações

- Ujian SPSS TatiDocumento21 páginasUjian SPSS TatiLina NaiwaAinda não há avaliações

- SAT Math Notes: by Steve Baba, PH.DDocumento6 páginasSAT Math Notes: by Steve Baba, PH.DAnas EhabAinda não há avaliações

- Lesson 6.1 - Managing ICT Content Using Online PlatformsDocumento9 páginasLesson 6.1 - Managing ICT Content Using Online PlatformsMATTHEW LOUIZ DAIROAinda não há avaliações

- Feetwood Battery Control CenterDocumento9 páginasFeetwood Battery Control Centerfrank rojasAinda não há avaliações

- Rev.8 RBMviewDocumento216 páginasRev.8 RBMviewdford8583Ainda não há avaliações

- WindowsDocumento52 páginasWindowskkzainulAinda não há avaliações

- Building Boats - A Kanban GameDocumento9 páginasBuilding Boats - A Kanban GameTim WiseAinda não há avaliações

- Revision Notes - HardwareDocumento18 páginasRevision Notes - HardwaremuhammadAinda não há avaliações

- Authorization LetterDocumento4 páginasAuthorization LetterCherry Mae CarredoAinda não há avaliações

- IoT Security in Higher EdDocumento16 páginasIoT Security in Higher EdBE YOUAinda não há avaliações

- OMEN by HP 17 Laptop PC: Maintenance and Service GuideDocumento99 páginasOMEN by HP 17 Laptop PC: Maintenance and Service GuideGustavo TorresAinda não há avaliações

- Business Level Strategy of GrameenphoneDocumento11 páginasBusiness Level Strategy of GrameenphoneummahshafiAinda não há avaliações

- VideoXpert OpsCenter V 2.5 User GuideDocumento55 páginasVideoXpert OpsCenter V 2.5 User GuideMichael QuesadaAinda não há avaliações

- Arrangement Description ManualDocumento22 páginasArrangement Description ManualheriAinda não há avaliações

- Summer Jobs 2020Documento6 páginasSummer Jobs 2020Mohammed AshrafAinda não há avaliações

- Create Table PlayerDocumento8 páginasCreate Table PlayerMr MittalAinda não há avaliações

- DDDDocumento3 páginasDDDNeelakanta YAinda não há avaliações

- ANNEX4Documento15 páginasANNEX4Nino JimenezAinda não há avaliações

- Jeannette Tsuei ResumeDocumento1 páginaJeannette Tsuei Resumeapi-282614171Ainda não há avaliações

- Remote SensingDocumento31 páginasRemote SensingKousik BiswasAinda não há avaliações

- Zimbra Collaboration Product OverviewDocumento4 páginasZimbra Collaboration Product OverviewStefanus E PrasstAinda não há avaliações