Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

63 PDF

Enviado por

imeldafitriTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

63 PDF

Enviado por

imeldafitriDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

International Journal of Health Sciences and Research

www.ijhsr.org ISSN: 2249-9571

Review Article

Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

Ms. Sarika Tyagi1, Dr. Gurudayal Singh Toteja2, Dr. Neena Bhatia3

1

Ph.D Scholar, Department of Food and Nutrition, Lady Irwin College, University of Delhi,

2

Scientist „G‟ and Head, Division of Nutrition and CNRT, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi,

3

Associate Professor and Head, Department of Food and Nutrition, Lady Irwin College, University of Delhi,

Corresponding Author: Ms. SarikaTyagi

ABSTRACT

This study aimed at establishing a relation between maternal nutritional status and birth weight

through a literature search. For this review more than 200 research articles have been screened out on

the subject and 101 relevant studies have been identified and included in paper writing. Maternal

nutritional status could be considered as primary predictor factor for birth weight of infants. This

relationship is influenced by many factors. Dietary intake during pregnancy is the main determinant of

birth weight. Not only macronutrients but micronutrients also play important role in the growth and

development of fetus. Micronutrient status during pregnancy is correlated with the birth weight of

neonate. Prepregnancy maternal weight <45 kg, height <145 cm and low BMI <18.5kg/m2 are

associated with low birth weight and adverse birth outcomes. Low socio economic status is the

strongest predictor for low birth weight. Although it does not affect it directly but indirectly it affects

all the variables that can directly cause low birth weight. Educational level of mother also plays

important role. Hence maternal nutritional status is the major factor affecting the fetal growth and

birth weight and is influenced by many biological, social and demographic factors.

Key Words: Maternal nutritional status, adverse birth outcomes, Low birth weight

INTRODUCTION survival, future physical growth and mental

Maternal nutritional status could be development. Birth weight indicates the

considered as primary predictor for the quality of life, socio- economic status,

nutritional status of neonates, however the health awareness and nutritional status of

association between maternal nutrition and the community. [2] Researches from

birth outcome is complex and is influenced different part of the world from time to time

by many biological, socio economic and indicated a close relation between the

demographic factors. The state of maternal maternal nutritional status and the health of

nutrition is one of the important the pregnant woman and her offspring.

environmental factors which might be Maternal nutrition before and during

expected to influence the course of pregnancy may play an important role in

pregnancy. The growth of fetal tissues and maternal, neonatal, and child health

other products of conception and the outcomes [3] hence this study aimed at

metabolic alterations consequent on establishing a relation between the

pregnancy impose great stress and result in nutritional status of mother and birth weight

an increase in the expectant mother's of the new born.

nutritional requirements. [1] The birth weight

of an infant is a reliable index of intrauterine

growth and a major factor determining child

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 422

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

METHOD mothers with higher intakes of milk at 18

For this review we searched week and green leafy vegetables and fruits

PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar at 28 week had larger infants almost 200g

using terms related to nutritional status of heavier than those who never ate them. [8]

pregnant women and relation with birth Women who consumed less or no milk gave

weight (“maternal nutritional status” OR birth to infants who weighed less than those

“nutritional status during pregnancy” born to women who consumed more milk.

[9,10]

“Dietary intake in pregnancy and birth while the lengths and head

weight” OR “Micronutrient profile in circumferences were similar. [9] Dietary

pregnancy and birth weight” OR “Maternal diversity was positively correlated with

anthropometry and birth weight ” OR nutrient intake and nutritional status. [11]

“Socio- economic status and birth weight”). 1.2 Macro nutrient intake: Prevalence of

More than 200 research articles have been low birth weight (LBW) was higher

screened out on the subject and the significantly among pregnant women with

references of retrieved full-text articles were mean caloric intake of less than 70% of the

examined for additional articles. 99 relevant RDA [2,12-13] and protein intake of less than

studies showing correlation with birth 40 gm (60%), during the last trimester of

weight have been identified and included in pregnancy. [12] Calorie intake during

paper writing. pregnancy is positively associated with the

1. Dietary intake during pregnancy and birth weight of the newborn. [8,14-15] Energy

birth weight supplementation to chronically

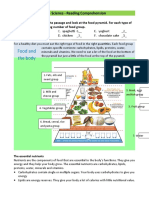

“Eat for two during pregnancy” is an old undernourished populations in sufficient

saying. To check the truthfulness of these quantity and duration lead to significant

words or impact of maternal dietary intake increase in birth weight as well as decreases

during pregnancy on the nutritional status of in rates of LBW and small for gestational

offspring researchers across the world age (SGA) birth. [16] Birth weight of

conducted numerous studies. Nutritional neonates was correlated significantly with

status of neonate is dependent upon macro Energy, protein and calcium intakes during

and micronutrient intake of mother and third trimester. [17-18] Observational studies

inadequate dietary intake during this rapid suggested that maternal fat intake might be

growth phase of gestation results in growth associated with gestational weight gain. [19]

failure. Recommended dietary allowances Higher fat intake at week 18 was associated

(RDA) for Indians, ICMR, 2010 with neonatal length (p<0.001), birth weight

recommended additional intake of energy (p<0.05) and triceps skin fold thickness

by 350 kcal/day and protein by 23 gm/day . (p<0.05). [8] Low concentrations of most n-3

Fat intake should increase to 30gm/day, fatty acids and 20:3 n-6 and high

calcium 1200 mg/day, iron 35 mg/day and concentrations of 20:4 n-6 remained

retinol 800 µg/day. [4] International associated with lower birth weight, higher

Organizations (FAO/ WHO/ UN) SGA risk, or both. [20-21] Consumption of

recommended that pregnant women should low saturated fatty acids was associated

increase their energy intake by 85 kcal/ day with decreased birth weight and an

during first trimester, 285 kcal/ day during increased risk of SGA. [21] Significantly

second trimester and 475 kcal/ day during higher risk of LBW was found among

third trimester. [5] pregnant women who did not eat fish or had

1.1 Intake of Different Food groups: Poor low EPA (Eicosapentaenoic acid) intake

women from rural as well as urban area during third trimester. [22]

have low intakes of a range of micronutrient 1.3 Micronutrient Intake: Majority of

dense foods such as green leafy vegetables, pregnant women are consuming <50 % of

fruits and dairy products. [6,7] The Pune the recommended calories moreover 99,

Maternal Nutrition study find out that 86.2, 75.4, 23.6 and 3.9 percent of the

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 423

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

pregnant women were consuming <50% of Pregnancy is a period of increased

the recommended folic acid, zinc, iron, metabolic demands, with changes in the

copper and magnesium respectively. [23-24] woman‟s physiology and the requirements

Some studies found no relation between of a growing foetus. [36] During this time

mean birth weight of infants and maternal inadequate stores or intake of vitamins and

energy and protein intake but instead minerals, collectively referred as

demonstrated a stronger relationship with micronutrients, can have adverse effects on

dietary intake of micronutrient rich foods [8] the mother, such as anemia, hypertension,

or low positive correlation between the complications of labor and even death. [37] In

mean dietary iron, folic acid, carotene and South East Asia, iron deficiency and anemia

[25]

vitamin B12 intake. Iron affect more than 40% of pregnant women

supplementation considering total iron and the prevalence of folic acid deficiency

intake from food and supplements, is may be upto 30-50%. [38-39]

significantly associated with increased birth 2.1 Anemia: The prevalence of low LBW,

weight [26-28,8] and the association was preterm birth, perinatal mortality, and

stronger in the high vitamin C intake group. neonatal mortality was significantly higher

[27]

Each mg increase in vitamin C was among anemic pregnant women. Overall, in

associated with a 50.8 g increase in birth low- and middle-income countries, 12% of

weight. [29] Neonatal measurements were LBW, 19% of preterm births, and 18% of

also related to maternal folate and vitamin C perinatal mortality were attributable to

status independent of food intake. [30] maternal anemia. [38] A significant relation

Appropriate birth weight and 1-min was found between maternal haemoglobin

Apgar score of newborns was significantly level and pregnancy outcome such as type

correlated with adequate maternal calcium of delivery and birth weight. [40] Maternal

and vitamin D intake and weight gain of anemia was an independent risk factor for

mothers during pregnancy. [31] Optimal preterm delivery, [41-43] LBW, [41,43-45] low

calcium intake and adequate maternal Apgar scores and intrauterine fetal death. [43]

vitamin D status are both needed to The cord serum iron, transferrin saturation

maximize fetal bone growth and and ferritin concentrations had significant

improvement in status of these nutrients correlation with maternal haemoglobin. The

may have a positive effect on fetal skeletal significant low levels of these parameters

development. [32] Birth weight was suggested that maternal anaemia adversely

positively associated with increasing affected the iron status including iron stores

pantothenic acid/ biotin ratios (P=0.011), of the newborns. [46] Perinatal mortality was

magnesium (P=0.000) and vitamin D increased with exposure to Hb < 7.0 g/dl. [47]

(P=0.015) intakes during pregnancy. [28] Iron supplementation was significantly

However, studies from developed associated with birth weight. Maternal

countries showed that high calorie and hemoglobin was significantly higher (+5.56

protein intake exceeding the RDA, do not g/L) for mothers who had iron

help but have adverse effect on birth weight, supplementation [48] and those not received

[33-34]

and a higher intake of protein iron supplementation during pregnancy

associated with a reduction in birth weight were more likely to have LBW infants. [49]

and a reduced ponderal index among large The risk of having smaller than average

birth weight infants but not LBW infants. birth size newborn was significantly reduced

[34]

There is need for proper, adequate and by 18% for mothers who used any IFA

balanced micronutrient during pregnancy to supplements compared with those who did

affect neonates as healthy outcome. [35] not. [50] Infants of iron-depleted mothers, as

2. Micronutrient Deficiency during indicated by maternal serum ferritin had

pregnancy and birth weight lower cord-blood serum ferritin than the

mothers who had adequate levels [51-52] and

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 424

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

between anemic and non anemic groups, increased pregnancy loss, mental

mean gestational age, weight, length and retardation, cretinism and preterm delivery

[59]

head circumference of the neonates differed but less is known for other outcomes

significantly (p<0.01). [53] Prevalence of iron especially in case of marginal iodine

deficiency was higher among infants born to deficiency. [37] Urinary iodine concentration

iron deficient mothers as compared to the (UIC) below 1.0 mg/L, was significantly

infants born to healthy mothers. [54-55] positively associated with birth weight and

2.2 Vitamin B-12 Deficiency: Vitamin B- length. Birth weight and length increased by

12 insufficiency was 21%, 19%, and 29% in 9.3 g and 0.042 cm, respectively for each

the first, second, and third trimesters, 0.1-mg/L increase in maternal urinary

respectively, with high rates for the Indian iodine concentration. No associations were

subcontinent and the Eastern Mediterranean. observed between maternal urinary iodine

[56]

There is a relationship between concentration and head or chest

increasing antenatal vitamin B12 circumference. [63]

concentrations and birth weight in Indian 2.5 Deficiency of Minerals and Trace

babies. The low maternal vitamin B12 status elements: Deficiency of minerals such as

translates into a low neonatal vitamin B12 magnesium, selenium, copper and calcium

status as evinced by cord serum vitamin have also been associated with

B12 concentrations. [57] Lower vitamin B12 complications of pregnancy, child birth or

[59]

concentrations during each of the three fetal development. Magnesium

trimesters of pregnancy had significantly restriction did not affect the birth weight but

higher risk of delivering an IUGR (Intra if continued postnatally through lactation

uterine growth retardation) [57] or LBW [58] and weaning, it decreased the body weight

baby, when compared to women with higher of the offsprings at weaning and thereafter.

[60]

concentrations. Except magnesium, the profile of other

2.3 Zinc deficiency: Zinc deficiency has biochemical variables, namely, calcium,

been associated in some but not all studies zinc and iron in the umbilical cord blood of

with complications of pregnancy and the neonates with normal birth weight

delivery, as well as with growth retardation, (NBW) were significantly higher than in the

congenital abnormalities and retarded umbilical cord blood of neonates with

neurobehavioural and immunological LBW. [35]

development in foetus. [59] Maternal zinc 2.6 Micronutrient Supplementation

restriction significantly decreased the birth during pregnancy: There is controversy on

weight and body weight of the offsprings at whether dietary micronutrient

later time point. [60] Birth weight of children supplementation in pregnancy can increase

of mothers in the zinc supplemented group birth weight. Dietary supplementation and

were significantly higher (300 to 800 g oral multiple-micronutrient (MMN)

difference) than the birth weight of children supplementation during pregnancy was

of mothers in the control group. [61] associated with increase in maternal weight

Goldenberg et al, 1995 revealed that all gain and mean birth weight and a significant

women, infants in the zinc supplemented decrease in the prevalence of LBW or SGA

group have a significantly greater birth infants and a reduced rate of still birth. [64-

65]

weight (126g, P= 0.3) and head No significant differences were shown

circumference (0.4 cm, p= 0.2) than infants for other maternal and pregnancy outcomes

in the placebo group. [62] Maternal serum such as preterm births, maternal anemia,

zinc, iron and calcium concentration miscarriage, maternal mortality, perinatal

influenced the birth weight of neonates as mortality, neonatal mortality or risk of

outcome of pregnancy. [35] delivery via a caesarean section. [65] Small

2.4 Iodine deficiency: Severe iodine benefits from early food and multiple

deficiency during pregnancy results in micronutrient supplementations were found

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 425

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

in infants of low-BMI but not of high-BMI second trimester (< 5.7 Kg) was associated

mothers. [66] Multiple micronutrient with decreased birth weights ranging from

supplementations resulted in a 27% 48 to 248 gm, depending on the pattern of

reduction in the rate of stunting. An effect weight gain in the other trimesters. [78] The

of the MMN supplementation on weight- WHO collaborative study reported that

for-length and head circumference-for-age mothers in the lowest quartile of

became apparent by the end of the first year prepregnancy weight carried an elevated

of life. By the age of 30 months, children risk of IUGR and LBW of 2.55 and 2.38

from the supplementation group had a respectively compared to the upper quartile.

higher weight-for-height. [67] The findings, [79

consistently observed in several systematic 3.2: Maternal Height: Children whose

evaluations of evidence, provide a strong mother‟s height was <145 cm, had two-fold

basis to guide the replacement of iron and higher odds of being stunted. [75]

folic acid with MMN supplements 3.3 Mid upper arm circumference

containing iron and folic acid for pregnant (MUAC): The MUAC values below which

women in developing countries where most adverse effects were identified were

MMN deficiencies are common among <22 and <23 cm and hence a conservative

women of reproductive age. Efforts should cut-off of <23 cm is recommended to

be focused on the integration of this include most pregnant women at risk of

intervention in maternal nutrition and LBW for their infants in the African and

antenatal care programs in developing Asian contexts. [80]

countries. [65] Low weight and height of mothers were

3. Maternal anthropometry and birth associated with increased risk of perinatal

weight death, prematurity and SGA [80] and child‟s

Maternal stature is a composite nutritional status as indicated by weight for

indicator that represents the genetic and age, was associated with BMI of the mother

environmental effects on the growing period (P<0.001). [81]

of childhood. Poor nutrition of mother, both 3.4 Body Mass Index (BMI): Women with

before and during pregnancy, contributes to low BMI were found to have a higher

impairment of fetal development and probability of delivering a LBW baby2,

contributes to LBW and in turn to high rates 35.4% of very low BMI and 33.7% of low

of stunting. [68] Pregnancy outcomes can be BMI group delivered LBW babies as

better predicted by anthropometric compared to 24% women in normal BMI

measurements than dietary intake [69] and group. [82] NNMB data reported that mean

maternal measurements such as height, birth weights showed definite differences

weight, BMI and fundal height were between BMI classes. The odds ratio for

correlated significantly with birth weight. LBW was found to be three times more in

[70-73]

Pre pregnancy maternal weight (<45 severe chronic energy deficiency groups

kgs) and maternal height (<145 cms) are compared to normal BMI groups of

significant risk factor for LBW. [74-76] mothers. [83] Prevalence of low BMI

Maternal height, weight and skinfold (<18.5kg/ m2) in adult women has decreased

thickness at 6 and 9 month of pregnancy in Africa and Asia since 1980, but remains

were positively associated with mean birth higher than 10% in these two large

weight. developing regions.

3.1 Maternal weight: Mean maternal During the same period, prevalence

weight at the first prenatal visit and at 6 and of overweight (BMI >25 kg/ m2) and

9 month of pregnancy were positively obesity (BMI >30 kg/ m2) has been rising in

associated with birth length and with linear all regions. Maternal obesity leads to several

growth between birth and 4,3 and 6 months adverse maternal and fetal complications

of age. [77] Low maternal weight gain in the during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum.

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 426

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

There are four times more chances to were on average 290 and 260 gm higher

develop gestational diabetes and two times respectively than of uneducated and lower

more chances to develop pre-eclampsia income groups. [92] Most of the LBW (50%)

among obese women compared to women infants came from the group of mothers

with normal BMI. Low maternal BMI in without education but in NBW group 37%

early pregnancy also put infants at higher came from the mother completed primary

risk of SGA. BMI of 25 or greater was education and 53% (238/448) from mother

somewhat protective against term and who completed secondary level or above.

preterm SGA. [84] These data showed significant relationship

More studies are needed before BMI between LBW and poor educational status.

and weight gain can be used as a robust Majority of the mother (79.2%) in LBW

measure to determine when intervention is came from poor economical class in

needed, but it is clear that low BMI (<18.5 comparison to mother of NBW (67.4%)

kg/m2) during pregnancy and low maternal showing association between LBW and

weight is associated with smaller infant size. poor socioeconomic status. [93]

[85]

Determinants for non-utilization of

4. Socio- economic status and birth ANC were poverty, literacy, migration,

weight duration of stay in the slum area and high

Socio-economic status (SES) is a parity. [94] Risk of malnutrition was more

complex construct that has been used to than twofold higher in pregnant women with

define social inequality and usually includes low and medium autonomy of household

measures of income, occupation and/ or decision-making than those who had high

educational attainment. [86] SES do not affect level of autonomy in household decision-

the fetal growth directly but rather affects making. [95]

the variables which are directly affecting the Improved long-term nutritional

adverse outcomes such as quality of diet, situation and living conditions seems to be

antenatal care, maternal anthropometry, the most important prerequisites to

physical work and psychological factors counteract LBW in developing countries. [96]

such as stress, anxiety and depression. The overall prevalence of anemia was found

Women of low SES are at increased risk of to be high among illiterate (98.2%), Hindu

delivering LBW babies, [87-90] whether SES (92.31%) and moderately working woman

is defined by income, occupation or (83.34%). [97]

education. Studies of maternal dietary intake

Educational level has been the have also confirmed the importance of socio

strongest and most consistent predictor of economic status. Among rural Indian

health among social variables. A low women, intake of dairy products was

educational level limits access to jobs and strongly associated with SES and was also

other social resources especially in associated with birth size. [8] Mother with no

industrialized countries and thus increases education and from low income family was

the risk of poverty. [86] Education may also more likely to have LBW infant compared

have independent effects, above and beyond with mother with higher education and from

income, because more highly educated higher income family. [98] Chronic

mothers may know more about family malnutrition was associated with mother‟s

planning and healthy behaviours during age and educational level, type of residence,

pregnancy. [87] Mother‟s level of education number of rooms, flooring, water supply,

may be considered as the most important and LBW (< 2,500 g) in children aged ≤ 24

determinant of birth weight. Low level of months. [99]

mother‟s education was predictor for LBW. Kramer et al observed that the

[91]

Mean birth weights of neonates of the countries which had achieved the lowest

higher educated and high income group rates of adverse birth outcomes had done so

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 427

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

not through health care interventions but REFERENCES

rather by reducing the prevalence of socio- 1. Venkatachalam PS. Maternal nutritional

economic disadvantage. It may not be status and its effect on the

possible to eliminate the higher risks of newborn. Bulletin of the World Health

Organization. 1962;26(2):193-201.

IUGR and preterm birth among the poor

2. Metgud CS, Niak V A and Mallapur

without eliminating poverty itself. [86] M.D.; Effect of maternal nutrition on

birth weight of newborn- A community

CONCLUSION based study, The Journal of Family

Nutrition has profound effect on welfare 2012; 58(2); 35-39.

health throughout life but it plays very 3. Ramakrishnan U, Manjrekar R, Rivera

crucial role in influencing fetal growth and J, Gonzáles-Cossío T, Micronutrients

birth outcomes. It is a modifiable risk factor and pregnancy outcome: A review of

of public health importance. Macronutrient the literature. Nutrition Research 1999;

supplementation showed a positive effect in 19 (1) , 103-159,

developing countries. Micronutrient profile 4. Nutrient requirement & recommended

dietary allowances for Indians. A report

during pregnancy plays a major role by

of the Expert Group of the Indian

affecting birth weight and other birth Council of Medical Research, Indian

outcomes and is influenced by dietary intake council of Medical rsearch, New Delhi,

before and during pregnancy. Maternal 2010.

height, weight and skinfold thickness were 5. Food and Agricultural Organization /

positively associated with mean birth weight World Health Organization/ United

and mothers with low BMI were found to Nations University. Energy and protein

have a higher probability of delivering a requirements. Report of a joint FAO/

LBW baby. Socio economic status is one WHO/ UNU consultation. (WHO

such factor that may underpins many other technical report series no. 724) Geneva,

aetiological factors. Education plays a major Switzerland: World Health

role and affects all the aetiological factors Organization, 1985.

6. Bam ji, MS; Less recognized

for LBW and unexpected birth outcomes. micronutrient deficiencies in India. NFI

Although supplementary nutrition Bull.1998, 19: 5-8.

programme has been initiated by Govt. of 7. Murthy KVS, Reddy K.J.; Dietary

India to improve the nutritional status of patterns and selected anthropometric

vulnerable group but undernutrition still indices in reproductive age women of a

continues to be a major health problem in slum in urban Kurnool. Indian J of

India, the most vulnerable groups being Public Health. 1994; 38(3): 99-102.

women of reproductive age group and 8. Durrani AM and Rani A; Effect of

young children. Lack of awareness about Maternal dietary intake on the weight of

the nutritional programmes and importance newborn in Aligarh city India. Niger

of adequate nutrition during pregnancy is Med J. 2011 52(3): 177–181.

9. Mannion CA, Gray-Donald K, Koski

the major factor for unutilization of health KG; Association of low intake of milk

services. All these factors are interrelated so and vitamin D during pregnancy with

influencing each other. Hence it is necessary decreased birth weight; Canadian

that educational interventions must be Medical Association Journal. 2006;

provided along with the supplementary 25;174(9):1273-7.

nutrition programmes so that the services 10. Olsen SF, Halldorsson TI, Willett W C,

provided can be fully utilized by the target Knudsen VK, Gillman MW, Mikkelsen

groups. TB, Olsen J, and The NUTRIX

Consortium; Milk consumption during

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT(S) pregnancy is associated with increased

This research was financially supported by infant size at birth: prospective cohort

Indian Council of medical Research, New Delhi, study ; Am J Clin Nutr ;2007 ; 86 ( 4);

by providing Senior Research Fellowship. 1104-1110.

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 428

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

11. Willy K, Judith K, Peter C. Dietary 21. Mani I, Dwarkanath P, Thomas T, et al;

diversity, nutrient intake and nutritional Maternal fat and fatty acid intake and

status among pregnant women in birth outcomes in a South Indian

Laikipia county, Kenya. Int J Health Sci population; International Journal of

Res. 2016; 6(4):378-385. Epidemiology, 2016; 45(2); 523–531

12. Rao B T, Aggarwa A K, Kumar R; 22. Muthayya S, Dwarkanath P, Thomas T,

Dietary intake in third trimester of et al. The effect of fish and ω-3

pregnancy and prevalence of LBW: A LCPUFA intake on low birth weight in

community-based study in a rural area indian pregnant women. Eur J Clin

of Haryana, Indian Journal of Nutr. 2009; 63: 340–6.

community Medicine :2007; 32(4);272- 23. Pathak P, Kapil U, Dwivedi SN, et al;

276. Serum zinc levels amongst pregnant

13. Choudhary AK, Choudhary A, Tiwari women in a rural block of Haryana

SC, Dwivedi R; Factors associated with state, India. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;

low birth weight among newborns in an 17 (2); 276-9.

urban slum community in Bhopal; 24. Pathak P, Kapil U, Kapoor SK, et al;

Indian Journal of Public health; 2013; Prevalence of multiple micronutrient

57(1): 20-23 deficiencies amongst pregnant women

14. Lechtig A, Habicht JP, Delgado H et al; in a rural area of Haryana. Indian J

Effect of food supplementation during Pediatr. 2004; 71(11): 1007-14.

pregnancy on birthweight. Pediatrics. 25. Kolte D, Sharma R, Vali S. Correlates

1975; 56(4); 508 -520 between micronutrient intake of

15. Moore VM, Davies M J, Willson K J, pregnant women and birth weight of

Worsley A, and Robinson J S: Dietary infants from Central India. The Internet

Composition of Pregnant Women Is Journal of Nutrition and Wellness.

Related to Size of the Baby at Birth. J. 2009;8(2). DOI: 10.5580/1979

Nutr., 2004 ; 134 ( 7); 1820-1826 26. Grieger JA and Clifton VL; A Review

16. Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, et of the Impact of Dietary Intakes in

al. Community based interventions for Human Pregnancy on Infant

improving perinatal and neonatal health Birthweight; Nutrients 2015, 7, 153-

outcomes in developing countries: a 178.

review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 27. Alwan NA, Greenwood DC, Simpson

2005; 115 (2 suppl): 1295s-1303s. NA, et al. Dietary iron intake during

17. Khoushabi F and Saraswathi G ; Impact early pregnancy and birth outcomes in a

of nutritional status on birth weight of cohort of British women. Hum

neonates in Zahedan City, Iran. Reprod. 2011 Apr; 26(4):911-9.

Nutrition Research and Practice 28. Watson PE, Skeletal growth in utero in

2010;4(4): 339-344 pregnant adolescent; Am J Clin

18. Moghaddam Tabrizi F, Saraswathi G. Nutr. 2012 May; 95(5): 1103–1112.

Maternal anthropometric measurements 29. Mathews F, Yudkin P, Neil A. Influence

and other factors: relation with birth of maternal nutrition on outcome of

weight of neonates. Nutrition Research pregnancy: prospective cohort study.

and Practice. 2012;6(2):132-137. BMJ. 1999;319(7206):339–343.

19. Tielemans MJ, Garcia AH, Peralta 30. Rao S, Yajnik CS, Kanade A, Fall

Santos A, et al. Macronutrient CHD, Margetts BM, Jackson AA, Shier

composition and gestational weight R, Joshi S, Rege S, Lubree H, Desai B.

gain: a systematic review. Am J Clin Intake of micronutrient-rich foods in

Nutr. 2016; 103(1):83-99. rural Indian mothers is associated with

20. Van Eijsden M, Hornstra G, van der the size of their babies at birth: Pune

Wal MF, et al. Maternal n-3, n-6, and Maternal Nutrition Study. J. Nutr.

trans fatty acid profile early in 2001;131:1217–24.

pregnancy and term birth weight: a 31. Sabour H, Hossein-Nezhad A,

prospective cohort study. Am J Clin Maghbooli Z, Madani F, Mir E, Larijani

Nutr. 2008;87(4):887–895 B. Relationship between pregnancy

outcomes and maternal vitamin D and

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 429

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

calcium intake: A crosssectional study. hospital in Pakistan. East Mediterr

Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:585-9. Health J. 2004 Nov;10(6):801-7.

32. Young B E, McNanley T J,Cooper EM 42. Kumar A, Maternal indicators and

et al; Maternal Vitamin D status and obstetric outcomes in the north indian

calcium intake interact to affect fetal population; a hospital based study. J

skeletal growth in utero in pregnant Postgrad Med. 2010 Jul- Sep; 56(3):

adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 192-5

;95(5):1103-12. 43. Levy A, Fraser D, Katz M, Mazor

33. Sloan et al., "The effect of prenatal M, Sheiner E.Maternal anemia during

dietary protein intake on birth pregnancy is an independent risk factor

weight", NUTR RES, 21(1-2), 2001, pp. for low birthweight and preterm

129-139; delivery; Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod

34. Andreasyan K and Ponsonby AL and Biol. 2005 Oct 1;122(2):182-6.

Dwyer T et al; Higher maternal dietary 44. Agrawal S, Agarwal A, Bansal AK;

protein intake in late pregnancy is Birth weight pattern in rural

associated with a lower infant ponderal undernourished pregnant women;Indian

index at birth, European Journal of Pediatr.2002; 39 (3): 244- 53

Clinical Nutrition, 61, (4) pp. 498-508. 45. Ganesh Kumar S, Harsha Kumar

ISSN 0954-3007 (2007) HN, Jayaram S, Kotian MS.

35. Khoushabi F, Shadan MR, Miri A et al; Determinants of low birth weight: a

Determination of maternal serum zinc, case control study in a district hospital

iron, calcium and magnesium during in Karnataka. Indian J Pediatr. 2010

pregnancy in pregnant women and Jan;77(1):87-9. doi: 10.1007/s12098-

umbilical cord blood and their 009-0269-9.

association with outcome of pregnancy. 46. Agrawal RM, Tripathi AM, Agarwal

Mater Sociomed. 2016 Apr; 28(2): 104- KN; Cord blood haemoglobin, iron and

107 ferritin status in maternal anaemia. Acta

36. King JC (2000) Physiology of Paediatr Scand. 1983 Jul;72(4):545-8.

pregnancy and nutrient metabolism. 47. Geelhoed D, Agadzi F, Visser

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition L, Ablordeppey E, Asare K, O'Rourke

71 (Suppl.), 1218- 1225. P, Van Leeuwen JS, Van Roosmalen J.

37. Ramakrishna U, Manjrekar R, Rivera J, Maternal and fetal outcome after severe

Gonzales Cossio T and Mortorell R anemia in pregnancy in rural Ghana.

(1999) Micronutrients and pregnancy Acta Obstet Gynecol

outcome: a review of literature. Scand. 2006;85(1):49-55.

Nutrition Research 19, 103-159. 48. Zhao G, Xu G, Zhou M, Jiang Y,

38. Rahman MM, Abe SK et al; Maternal Richards B, Clark KM, Kaciroti N,

anemia and risk of adverse birth and Georgieff MK, Zhang Z, Tardif T, Li

health outcomes in low- and middle- M, Lozoff B; Prenatal Iron

income countries: systematic review Supplementation Reduces Maternal

and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr Anemia, Iron Deficiency, and Iron

2016; 103:495–504 Deficiency Anemia in a Randomized

39. Seshadri S.; Prevalence of micronutrient Clinical Trial in Rural China, but Iron

deficiency particularly of iron, zinc and Deficiency Remains Widespread in

folic acid in pregnant women in South Mothers and Neonates. J Nutr. 2015

East Asia. Br. J Nutr. 2001 May; 85 Aug;145(8):1916-23.

Suppl 2:s87-92. 49. Khanal V, Zhao Y and Sauer K; Role of

40. Francis S & Nayak S; Maternal antenatal care and iron supplementation

haemoglobin level and its association during pregnancy in preventing low

with pregnancy outcome among birth weight in Nepal: comparison of

mothers.NUJHS Vol. 3, No.3, national surveys 2006 and 2011;

September 2013, ISSN 2249-7110 Archives of Public Health 2014, 72:4

41. Lone FW, Qureshi RN, Emmanuel F; 50. Nisar YB and Dibley MJ; Antenatal

Maternal anaemia and its impact on iron–folic acid supplementation reduces

perinatal outcome in a tertiary care risk of low birthweight in Pakistan:

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 430

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

secondary analysis of Demographic and 59. Black RE; Micronutrients in pregnancy.

Health Survey 2006–2007; Maternal British Journal of Nutrition (2001), 85,

and Child Nutrition (2016) 12, pp. 85– Suppl. 2, S193- S197.

98 60. Raghunath M, Venu L, Padmavati IJN,

51. Shao J, Lou J, Rao R, Georgieff Kishore YD et al, Modulation of

MK,Kaciroti N, Felt BT, Zhao macronutrient metabolism in the

ZY, and Lozoff B; Maternal serum offspring by maternal micronutrient

Ferritin concentration Is positively deficiency in experimental animals

associated with newborn iron stores in Indian J Med Res 130, November 2009,

women with low ferritin status in late pp 655- 665.

pregnancy; J Nutr. 2012 November; 61. Garg HK, Singhal KC and Arshad Z; A

142(11): 2004–2009. study of the effects of oral zinc

52. Alwan NA, Greenwood DC, Simpson supplementation during pregnancy on

NA, McArdle HJ, Godfrey KM, Cade pregnancy outcome. Indian J. Physiol.

JE. Dietary iron intake during early Pharmacol. 1993; 37; 276-284.

pregnancy and birth outcomes in a 62. Goldenberg RL, Tamura T, Cilver SP,

cohort of British women. Hum Cutter GR, Hoffman HJ, Copper RL;

Reprod. 2011 Apr;26(4):911-9. Serum folate and fetal growth

53. Kaur M, Chauhan A, Manzar MD, retardation: a matter of compliance.

Rajput MM; Maternal Anaemia and Obstet Gynecol. 1992: 79: 719-722.

Neonatal Outcome: A Prospective 63. Rydbeck F; Rahman A, Grand´er, M et

Study on Urban Pregnant Women; al; Maternal Urinary Iodine

Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Concentration up to 1.0 mg/L Is

Research. 2015 Dec, Vol-9(12): QC04- Positively Associated with Birth

QC08. Weight, Length, and Head

54. Hou XQ, Li HQ; Effect of maternal iron Circumference of Male Offspring. J.

status on infant‟s iron level: a Nutr. 144: 1438–1444, 2014.

prospective study; Zhonghua Er Ke Za 64. Cessey SM, Prentice AM, Cole TJ, et al.

Zhi. 2009 Apr; 47 (4): 291-5 Effects on birth weight and perinatal

55. Poyrazoğlu HG, Aygün AD, Üstündağ mortality dietary supplements in rural

B, Akarsu S, Yıldırma S; Iron status of Gambia: 5 year randomized controlled

pregnant women and their newborns trial. BMJ 1997; 315: 786-90.

and the necessity of iron 65. Haider BA, Bhutta ZA. Multiple-

supplementation in infants in Eastern micronutrient supplementation for

Turkey; Turk Arch Ped 2011; 46: 238- women during pregnancy. Cochrane

43. Database of Systematic Reviews 2015,

56. Sukumar N, Rafnsson SB, Kandala NB, Issue 11. Art. No.: CD004905. DOI:

Bhopal R, Yajnik CS, and Saravanan 10.1002/14651858.CD004905.pub4.

P:Prevalence of vitamin B-12 66. Tofail F, Persson LA, Arifeen SE,

insufficiency during pregnancy and its Hamadani JD, et al; Effects of prenatal

effect on offspring birth weight: a food and micronutrient supplementation

systematic review and meta-analysis, on infant development: a randomized

Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103:1232–51. trial from the Maternal and Infant

57. Muthayya S, Kurpad AV, Duggan C et Nutrition Interventions, Matlab

al. Maternal vitamin B12 status is a (MINIMat) study ; Am J Clin Nutr

determinant of intrauterine growth 2008;87:704 –11.

retardation in South Indians. Eur. J 67. Roberfroid D1, Huybregts L, Lanou

ClinNutr 2006; 60: 791- 801. H, Ouedraogo L, Henry MC, Meda

58. Sukumar N, Rafnsson SB, Kandala NB, N, Kolsteren P; MISAME study group.

Bhopal R, Yajnik CS, and Saravanan Impact of prenatal multiple

P:Prevalence of vitamin B-12 micronutrients on survival and growth

insufficiency during pregnancy and its during infancy: a randomized controlled

effect on offspring birth weight: a trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012 Apr;95(4):

systematic review and meta-analysis, 916-24.

Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103:1232–51.

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 431

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

68. Vir S.C; Improving women‟s nutrition Maharashtra, India; National Journal of

imperative for rapid reduction of Community Medicine Vol 2 Issue 3

childhood stunting in South Asia: Oct-Dec 2011;

coupling of nutrition specific 77. Fawzi WW; Maternal anthropometry

interventions with nutrition sensitive and infant feeding practices in Israel In

measures essential; Maternal & Child relation to growth in infancy. Am J Clin

Nutrition published by John Wiley & Nut; 1997 jun.

Sons Ltd Maternal & Child 78. Abrams, Barbara drph, rd; Selvin, steve

Nutrition(2016),12(Suppl.1),pp.72–90 PhD; Maternal Weight Gain Pattern and

69. Johnson AA, Knight EM, Edwards CH, Birth Weight; Obstetrics &

Oyemade UJ, Cole OJ, Westney OE, Gynecology: August 1995; volume 86,

Westney LS, Laryea H, Jones S;Dietary Issue 2.

intakes, anthropometric measurements 79. World health Organization. Maternal

and pregnancy outcomes. J Nutr. 1994 anthropometry and pregnancy

Jun;124(6 Suppl):936S-942S outcomes: a WHO collaborative study.

70. Khoushabi F and Saraswathi G ; Impact Bull World Health Organ 1995; 73

of nutritional status on birth weight of (Suppl) : 1-98.

neonates in Zahedan City, Iran. 80. Mavalankar DV, Trivedi CC and Gray

Nutrition Research and Practice RH; Maternal weight, height and risk of

2010;4(4): 339-344 poor pregnancy outcome in

71. Sen J, Roy A, Mondal N. Association of Ahmedabad, India. Indian Pediatrics,

maternal nutritional status, body volume 31- October 1994.

composition and socio-economic 81. Rahman M., S.K. Roy, M Ali, A.K.

variables with low birth weight in India. Mitra, A.N. Alam and M.S. Akbar;

J Trop Pediatr. 2010 Aug;56(4):254-9. Maternal nutritional status as a

doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmp102. determinant of child health; J Trop

72. Kumar A, Maternal indicators and Pediatrics (1993) 39 (2); 86-88.

obstetric outcomes in the north indian 82. Kumar A, Maternal indicators and

population; a hospital based study. J obstetric outcomes in the north indian

Postgrad Med. 2010 Jul- Sep; 56(3): population; a hospital based study. J

192-5. Postgrad Med. 2010 Jul- Sep; 56(3):

73. Sachar RK; Soni RK; Singh H; Kaur N; 192-5

Singh B; Kumar V; Sofat R; Correlation 83. Naidu AN, Rao NP, Body mass index :

of some maternal variables with birth a measure of the nutritional status in

weight. Indian Journal of Meternal and Indian populations. Eur J ClinNutr

Child Health. 1994 Apr-Jun; 5(2): 43-5 1994; 48 (Suppl 3) : S131- 40.

74. Ganesh Kumar S, Harsha Kumar 84. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP et al,

HN, Jayaram S, Kotian MS. Maternal and child undernutrition and

Determinants of low birth weight: a overweight in low income and middle

case control study in a district hospital income countries. The Lancet, volume:

in Karnataka. Indian J Pediatr. 2010 382, Issue: 9890.

Jan;77(1):87-9. doi: 10.1007/s12098- 85. Papathakis, P.C., et al., How maternal

009-0269-9. malnutrition affects linear growth and

75. Aguayo VM, Nair R, Badgaiyan N and development in the offspring, Molecular

Krishna V; Determinants of stunting and Cellular Endocrinology (2016),

and poor linear growth in children under http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2016.01.

2 years of age in India: an in-depth 024

analysis of Maharashtra‟s 86. Kramer MS, Seguin L, Lydon J, et al.

comprehensive nutrition survey; Socio economic disparities in pregnancy

Maternal & Child Nutrition (2016), 12 outcome: Why do the poor fare so

(Suppl. 1), pp. 121–140. poorly? Paediatr PerinatEpidemiol,

76. Deshpande J D, Phalke DB, Bangal V 2000; (14) 194 -210.

B;Maternal risk factors for low birth 87. Reichman NE; Low Birth Weight and

weight neonates; a hospital based case School Readiness; Journal Issue: School

control studying rural area of Western

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 432

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Sarika Tyagi et al. Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation with Birth Weight

Readiness: Closing Racial and Ethnic Determinants of Low Birth Weight, J

Gaps Volume 15 Number 1 Spring 2005 Dhaka Med Coll. 2008; 17(2) : 83-87.

88. Hirve SS, Ganatra BR.Determinants of 94. Ghosh-Jerath et al; Ante natal care

low birth weight: a community based (ANC) utilization, dietary practices and

prospective cohort study. Indian nutritional outcomes in pregnant and

Pediatr. 1994 Oct;31(10):1221-5. recently delivered women in urban

89. Deshmukh JS, Motghare DD, Zodpey slums of Delhi, India: an exploratory

SP and Wadhva SK;Low birth weight cross-sectional study. Reproductive

and associated maternal factors in an Health (2015) 12:20

urban area, Indian Pediatrics, Volume 95. Kedir H, Berhane Y and Worku A;

35-January 1998 Magnitude and determinants of

90. Thomre PS, Borle AL , Naik JD, malnutrition among pregnant women in

Rajderkar SS, Maternal Risk Factors eastern Ethiopia: evidence from rural,

Determining Birth Weight of community-based setting. Maternal and

Newborns: A Tertiary Care Hospital Child Nutrition 12 (2016), pp. 51- 63.

Based Study, International Journal of 96. Andersson R, Bergström S; Maternal

Recent Trends in Science And nutrition and socio-economic status as

Technology, ISSN 2277-2812 E-ISSN determinants of birthweight in

2249-8109, Volume 5, Issue 1, 2012 pp chronically malnourished African

03-08 women. Tropical Medicine and

91. Maddah M, Karandish M, International Health ,volume 2 no 11 pp

Mohammadpour-Ahranjani 1080–1087 november 1997.

B, Neyestani TR, Vafa R, Rashidi A. 97. Madhavi LH, Singh H.K.G; Nutritional

Social factors and pregnancy weight status of rural pregnant women;

gain in relation to infant birth weight: a People‟s Journal of Scientific Research;

study in public health centers in Rasht, vol. 4(2), July 2011

Iran. Eur J ClinNutr. 2005 Oct;59(10): 98. Islam M, Rahman S, et al; Effect of

1208-12. maternal status and breastfeeding

92. Karim E, Mascie-Taylor CG. The practices on infant nutritional status - a

association between birthweight, cross sectional study in the south-west

sociodemographic variables and region of Bangladesh; Pan Afr Med J.

maternal anthropometry in an urban 2013; 16: 139.

sample from Dhaka, Bangladesh. Ann 99. Silveira KBR, Alves JFR et al;

Hum Biol. 1997 Sep-Oct;24(5):387- Association between malnutrition in

401. children living in favelas, maternal

93. MatinA, Azimul SK, Maternal nutritional status, and environmental

Socioeconomic and Nutritional factors. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2010;86(3):

215-220

How to cite this article: Tyagi S, Toteja GS, Bhatia N. Maternal nutritional status and its relation

with birth weight. Int J Health Sci Res. 2017; 7(8):422-433.

***********

International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org) 433

Vol.7; Issue: 8; August 2017

Você também pode gostar

- Knowledge and attitude of primigravida mothers regarding antenatal dietDocumento6 páginasKnowledge and attitude of primigravida mothers regarding antenatal dietNeha RanaAinda não há avaliações

- Maternal and Early-Life Nutrition and HealthDocumento4 páginasMaternal and Early-Life Nutrition and HealthTiffani_Vanessa01Ainda não há avaliações

- Maternal Anthropometry and Low Birth Weight: A Review: G. Devaki and R. ShobhaDocumento6 páginasMaternal Anthropometry and Low Birth Weight: A Review: G. Devaki and R. ShobhaJihan PolpokeAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal PDFDocumento5 páginasJurnal PDFWaica PratiwiAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrients: Macronutrient and Micronutrient Intake During Pregnancy: An Overview of Recent EvidenceDocumento20 páginasNutrients: Macronutrient and Micronutrient Intake During Pregnancy: An Overview of Recent EvidenceAdib FraAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrients 08 00342 With CoverDocumento6 páginasNutrients 08 00342 With Coverredactor 1Ainda não há avaliações

- Background of The Study: Sleep, Nausea and Vomiting Were Shown To Have Contribution To Antenatal Life QualityDocumento12 páginasBackground of The Study: Sleep, Nausea and Vomiting Were Shown To Have Contribution To Antenatal Life QualityLizette Leah ChingAinda não há avaliações

- IntroductionDocumento3 páginasIntroductionZahra 9oAinda não há avaliações

- Faktor Sosio EkonomiDocumento9 páginasFaktor Sosio EkonomiGracemAinda não há avaliações

- (2023) - Relationship Between Diet Quality and Maternal Stool Microbiota in The MUMS Australian Pregnancy CohortDocumento12 páginas(2023) - Relationship Between Diet Quality and Maternal Stool Microbiota in The MUMS Australian Pregnancy CohortVisa LaserAinda não há avaliações

- Effectiveness of Nutritional Supplementation During The - 2022 - The Lancet RegDocumento11 páginasEffectiveness of Nutritional Supplementation During The - 2022 - The Lancet RegCawee CawAinda não há avaliações

- Kajian Kebijakan Dan Penanggulangan MasaDocumento7 páginasKajian Kebijakan Dan Penanggulangan MasaDodi DamaraAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition and Maternal Neonatal and Child Heal - 2015 - Seminars in PerinatoloDocumento14 páginasNutrition and Maternal Neonatal and Child Heal - 2015 - Seminars in PerinatoloVahlufi Eka putriAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition in Pregnancy: Basic Principles and RecommendationsDocumento7 páginasNutrition in Pregnancy: Basic Principles and Recommendationssuci triana putriAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrients 04 01958Documento19 páginasNutrients 04 01958Wahyu Arief MahatmaAinda não há avaliações

- Health and Nutritional Status of Certain Lactating Mothers of Bahawalpur, PakistanDocumento7 páginasHealth and Nutritional Status of Certain Lactating Mothers of Bahawalpur, PakistanDr Sharique AliAinda não há avaliações

- The Importance of Therapeutic Nutrition in Pregnancy: A Comprehensive ReviewDocumento4 páginasThe Importance of Therapeutic Nutrition in Pregnancy: A Comprehensive ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- Asistenciaeditorial,+3825 Eng EditorialDocumento3 páginasAsistenciaeditorial,+3825 Eng EditorialElizabeth GualeAinda não há avaliações

- 184-Article Text - 797-1-10-20151013Documento5 páginas184-Article Text - 797-1-10-20151013Bushra KainaatAinda não há avaliações

- retrospective cohrt7-bestDocumento21 páginasretrospective cohrt7-bestDegefa HelamoAinda não há avaliações

- Referencia 7. Santander 2021Documento30 páginasReferencia 7. Santander 2021Erie RegaladoAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Pregnant Women's Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Pregnancy Nutrition at A Tertiary Care HospitalDocumento6 páginasAssessment of Pregnant Women's Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Pregnancy Nutrition at A Tertiary Care HospitalInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyAinda não há avaliações

- The Relationship Between Dietary Patterns and Nutritional Knowledge With The Nutritional Status of Bajo Tribe Pregnant Women in Duruka District, Muna RegencyDocumento5 páginasThe Relationship Between Dietary Patterns and Nutritional Knowledge With The Nutritional Status of Bajo Tribe Pregnant Women in Duruka District, Muna RegencytreesAinda não há avaliações

- Bernatal Saragih Hidayat Syarief Hadi Riyadi Dan Amini NasoetionDocumento13 páginasBernatal Saragih Hidayat Syarief Hadi Riyadi Dan Amini NasoetionErniRukmanaAinda não há avaliações

- Bernatal Saragih Hidayat Syarief Hadi Riyadi Dan Amini NasoetionDocumento13 páginasBernatal Saragih Hidayat Syarief Hadi Riyadi Dan Amini NasoetionRachmad Emmen Ayahnya YasinAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition Counseling During Pregnancy On Maternal Weight GainDocumento4 páginasNutrition Counseling During Pregnancy On Maternal Weight GainAbha AyushreeAinda não há avaliações

- 1617-Article Text-9900-1-10-20170816Documento7 páginas1617-Article Text-9900-1-10-20170816hannaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Terbaru GiziDocumento11 páginasJurnal Terbaru GiziTasarane AngelAinda não há avaliações

- 37 72 1 SM PDFDocumento13 páginas37 72 1 SM PDFDesyAinda não há avaliações

- 2022 - The Importance of Nutrition in Pregnancy and Lactation - Lifelong ConsequencesDocumento26 páginas2022 - The Importance of Nutrition in Pregnancy and Lactation - Lifelong ConsequencesjacquelineAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal Gizi Indonesia (The Indonesian Journal of Nutrition)Documento10 páginasJurnal Gizi Indonesia (The Indonesian Journal of Nutrition)Maria NeleAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition in Pregnancy: Ensuring Health for Mother and BabyDocumento2 páginasNutrition in Pregnancy: Ensuring Health for Mother and BabyMegaAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal PICO 1 PDFDocumento5 páginasJurnal PICO 1 PDFrikaAinda não há avaliações

- 3003065usharanil PDFDocumento137 páginas3003065usharanil PDFArchana SahuAinda não há avaliações

- OK - EJMED KakfitDocumento5 páginasOK - EJMED Kakfitl_bajakanAinda não há avaliações

- Midwives and Nutrition During Preganncy - Contoh Literatuyr ReviewDocumento7 páginasMidwives and Nutrition During Preganncy - Contoh Literatuyr ReviewNansa PuspaAinda não há avaliações

- Abed,+1114 Impacts+of+Dietary+Supplements+and+Nutrient Rich+Food+for+Pregnant+Women+on+Birth+Weight+in+Sugh+El Chmis Alkhoms+–+LiDocumento8 páginasAbed,+1114 Impacts+of+Dietary+Supplements+and+Nutrient Rich+Food+for+Pregnant+Women+on+Birth+Weight+in+Sugh+El Chmis Alkhoms+–+LiLydia LuciusAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition in Pregnancy Basic Principles and RecommendationsDocumento6 páginasNutrition in Pregnancy Basic Principles and RecommendationsAndrea Hinostroza PinedoAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrients 15 03395Documento4 páginasNutrients 15 03395tomniucAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrients 12 00531Documento16 páginasNutrients 12 00531Zerry Reza SyahrulAinda não há avaliações

- Midwives and Nutrition Education During Pregnancy - A Literature RDocumento23 páginasMidwives and Nutrition Education During Pregnancy - A Literature RSuredaAinda não há avaliações

- Goodnight W. Optimal Nutrition For Improved....Documento14 páginasGoodnight W. Optimal Nutrition For Improved....cvillafane1483Ainda não há avaliações

- Effect of Balanced Protein Energy Supplementation During Pregnancy On Birth OutcomesDocumento9 páginasEffect of Balanced Protein Energy Supplementation During Pregnancy On Birth OutcomesAnonymous NQMP1x04t2Ainda não há avaliações

- Cagayan State University College of Allied Health SciencesDocumento16 páginasCagayan State University College of Allied Health SciencesAbby PangsiwAinda não há avaliações

- Dietary Guidelines For The Breast-Feeding WomanDocumento7 páginasDietary Guidelines For The Breast-Feeding Womanvicky vigneshAinda não há avaliações

- Maternal and Fetal Well BeingDocumento9 páginasMaternal and Fetal Well BeingRita ChatrinAinda não há avaliações

- Main (4Documento5 páginasMain (4Kevin KevinAinda não há avaliações

- Macronutrient and Micronutrient Intake During Pregnancy: An Overview of Recent EvidenceDocumento21 páginasMacronutrient and Micronutrient Intake During Pregnancy: An Overview of Recent EvidenceRENITAFEBRIANAAinda não há avaliações

- JURNAL 1dr - RaufDocumento6 páginasJURNAL 1dr - RaufCamelia Farahdila MusaadAinda não há avaliações

- Energy Requeriments During Pregnancy and LactationDocumento18 páginasEnergy Requeriments During Pregnancy and LactationManuela BesomiAinda não há avaliações

- Effect of Antenatal Dietary Interventions in Maternal Obesity On Pregnancy Weight Gain and Birthweight Healthy Mums and Babies (HUMBA) Randomized TrialDocumento13 páginasEffect of Antenatal Dietary Interventions in Maternal Obesity On Pregnancy Weight Gain and Birthweight Healthy Mums and Babies (HUMBA) Randomized TrialAripin Ari AripinAinda não há avaliações

- Nutritional Requirements OverviewDocumento6 páginasNutritional Requirements OverviewKoriaAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment of Nutrition Profile of Pregnant Women in Rural Area (Mymensingh District) of BangladeshDocumento6 páginasAssessment of Nutrition Profile of Pregnant Women in Rural Area (Mymensingh District) of BangladeshKanhiya MahourAinda não há avaliações

- Relationship Between Calcium Supplementation Dose and Vegetable Intake With PreeclampsiaDocumento7 páginasRelationship Between Calcium Supplementation Dose and Vegetable Intake With PreeclampsiaBrevi Istu PambudiAinda não há avaliações

- Reshmi DebnathDocumento27 páginasReshmi DebnathmahaAinda não há avaliações

- A Hospital Based Study On Knowledge in Women Regarding Food and Nutrients Intake During PregnancyDocumento5 páginasA Hospital Based Study On Knowledge in Women Regarding Food and Nutrients Intake During PregnancyiajpsAinda não há avaliações

- Nutrition Education and Counselling: An Essential Consideration To Optimise Maternal Nutrition and Pregnancy Outcomes in KenyaDocumento9 páginasNutrition Education and Counselling: An Essential Consideration To Optimise Maternal Nutrition and Pregnancy Outcomes in KenyaajmrdAinda não há avaliações

- Cme Reviewarticle: Current Concepts of Maternal NutritionDocumento14 páginasCme Reviewarticle: Current Concepts of Maternal NutritionAllan V. MouraAinda não há avaliações

- 10 1093@jn@nxy249Documento8 páginas10 1093@jn@nxy249Natali PamilanganAinda não há avaliações

- 383 Leiyla Elvizahro G2C007043Documento46 páginas383 Leiyla Elvizahro G2C007043Herlambang Cahyo NAinda não há avaliações

- Journal of Neonatal Nursing: ReviewDocumento6 páginasJournal of Neonatal Nursing: ReviewimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- CPNS Kemenkes 2019Documento38 páginasCPNS Kemenkes 2019imeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- 698 2956 1 PBDocumento4 páginas698 2956 1 PBimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Parasitologi Kebidanan: Edition Lea & Febiger Philadelphia 1984Documento3 páginasParasitologi Kebidanan: Edition Lea & Febiger Philadelphia 1984imeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Ikan Patin PDFDocumento9 páginasIkan Patin PDFimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- 79-Article Text-330-1-10-20181022Documento13 páginas79-Article Text-330-1-10-20181022imeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- 383 Leiyla Elvizahro G2C007043Documento46 páginas383 Leiyla Elvizahro G2C007043Herlambang Cahyo NAinda não há avaliações

- Crackers Enhanced with Striped Catfish and Carrot FlourDocumento8 páginasCrackers Enhanced with Striped Catfish and Carrot FlourimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- 78 Djoko Kartono - Sosialisasi AKGDocumento22 páginas78 Djoko Kartono - Sosialisasi AKGimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Implementasi Program Keluarga Sadar Gizi (Kadarzi) Di Kabupaten SemarangDocumento10 páginasImplementasi Program Keluarga Sadar Gizi (Kadarzi) Di Kabupaten SemarangimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Lampiran 3 Form Semi Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (SQ-FFQ)Documento5 páginasLampiran 3 Form Semi Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (SQ-FFQ)imeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- 78 Djoko Kartono - Sosialisasi AKGDocumento22 páginas78 Djoko Kartono - Sosialisasi AKGimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Article1385135472 - Rezaie Et AlDocumento5 páginasArticle1385135472 - Rezaie Et AlimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Pregnancy Weight Gain and Birth OutcomesDocumento10 páginasPregnancy Weight Gain and Birth OutcomesimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Article1385135472 - Rezaie Et AlDocumento5 páginasArticle1385135472 - Rezaie Et AlimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Energy and Protein Intake in Pregnancy (Review) : Kramer MS, Kakuma RDocumento84 páginasEnergy and Protein Intake in Pregnancy (Review) : Kramer MS, Kakuma RimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Midwifery Care Process FinalDocumento3 páginasMidwifery Care Process FinalNico Pieter100% (6)

- PDFDocumento5 páginasPDFimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- 10 5530ijopp 10 1 5 PDFDocumento6 páginas10 5530ijopp 10 1 5 PDFimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- 10 5530ijopp 10 1 5 PDFDocumento6 páginas10 5530ijopp 10 1 5 PDFimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Health Sciences and Research: Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation With Birth WeightDocumento12 páginasInternational Journal of Health Sciences and Research: Maternal Nutritional Status and Its Relation With Birth WeightimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- The SOAP Note FormatDocumento8 páginasThe SOAP Note Formatimeldafitri100% (1)

- 10 5530ijopp 10 1 5 PDFDocumento6 páginas10 5530ijopp 10 1 5 PDFimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Dok SydneyDocumento8 páginasDok SydneyimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Carbs - Good, Bad and WholegrainDocumento4 páginasCarbs - Good, Bad and WholegrainimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- PDFDocumento8 páginasPDFimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Perbandingan Kadar Protein Dan Lemak Dalam ASI "X", Susu Sapi Formula "Y" Dan Susu Kedelai Formula "Z"Documento13 páginasPerbandingan Kadar Protein Dan Lemak Dalam ASI "X", Susu Sapi Formula "Y" Dan Susu Kedelai Formula "Z"Karne AprillianyAinda não há avaliações

- The Effects of Oral Contraceptives On Detection and Pain Thresholds As Well As Headache Intensity During Menstrual Cycle in MigraineDocumento13 páginasThe Effects of Oral Contraceptives On Detection and Pain Thresholds As Well As Headache Intensity During Menstrual Cycle in MigraineimeldafitriAinda não há avaliações

- Top Notch 2 UNIT 4 - 5 - 6 VocabularyDocumento18 páginasTop Notch 2 UNIT 4 - 5 - 6 VocabularyRikardoAinda não há avaliações

- Neuro QuestionsDocumento19 páginasNeuro Questionssarasmith1988100% (6)

- Food Desert ArticleDocumento5 páginasFood Desert Articleapi-311434856Ainda não há avaliações

- Examination Content Guideline CDocumento5 páginasExamination Content Guideline CNHAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper - Body ImageDocumento13 páginasResearch Paper - Body Imageapi-495036140Ainda não há avaliações

- Nutrition and Health Tips for AdolescentsDocumento37 páginasNutrition and Health Tips for Adolescentseducare academyAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction of Mushroom: Presented By: Aadarsh Biswakarma Roll No: 62 BSC - Ag 5 SemDocumento14 páginasIntroduction of Mushroom: Presented By: Aadarsh Biswakarma Roll No: 62 BSC - Ag 5 SemArpan ChakrabortyAinda não há avaliações

- Brand Image Study of HorlicksDocumento23 páginasBrand Image Study of HorlicksM.E. Prakash100% (1)

- 1) Essay On Endangered AnimalsDocumento3 páginas1) Essay On Endangered AnimalsMindrilaAinda não há avaliações

- Food Pyramid Word WorksheetDocumento2 páginasFood Pyramid Word WorksheetAnabelAinda não há avaliações

- Literature ReviewDocumento5 páginasLiterature Reviewapi-534395189Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesson 9 WorksheetDocumento4 páginasLesson 9 WorksheetMashaal FasihAinda não há avaliações

- Why Is The Keto Diet Good For YouDocumento6 páginasWhy Is The Keto Diet Good For YouNema cringAinda não há avaliações

- PLR - Me Niche Attack Weight LossDocumento21 páginasPLR - Me Niche Attack Weight LossPieter du PlessisAinda não há avaliações

- Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi's Views On Food World Vegetarian Congress 1957Documento2 páginasBhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi's Views On Food World Vegetarian Congress 1957balasukAinda não há avaliações

- Kdigo 2013. CKDDocumento110 páginasKdigo 2013. CKDcvsmed100% (1)

- Junk Food's Harmful Effects and Healthy SolutionsDocumento18 páginasJunk Food's Harmful Effects and Healthy SolutionsMarcela CoroleaAinda não há avaliações

- The Matrix Is Real. Hack It! A Practical Guidebook PDFDocumento235 páginasThe Matrix Is Real. Hack It! A Practical Guidebook PDF2dlmediaAinda não há avaliações

- Heal Your Eye Problems With Herbs, Minerals and VitaminsDocumento117 páginasHeal Your Eye Problems With Herbs, Minerals and VitaminsAadilAinda não há avaliações

- NCP Post CSDocumento5 páginasNCP Post CSPeachy Marie AncaAinda não há avaliações

- Taller de InglesDocumento2 páginasTaller de InglesAndresAinda não há avaliações

- Lab Report For MonossacharideDocumento15 páginasLab Report For MonossacharideSay Cheez100% (1)

- PNG Native Chicken Production ProposalDocumento5 páginasPNG Native Chicken Production ProposalNathan RukuAinda não há avaliações

- Collagen Types 1Documento24 páginasCollagen Types 1hayiwadaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study 66 ReportDocumento16 páginasCase Study 66 ReportKalyan BarmanAinda não há avaliações

- Post Activity Log SheetDocumento3 páginasPost Activity Log SheetCarlyn Kerie SiguaAinda não há avaliações

- Estudio CalcioDocumento12 páginasEstudio CalciomarolinacinucheAinda não há avaliações

- 1.2 Growth and Production: 1.2.1 Tree SpacingDocumento9 páginas1.2 Growth and Production: 1.2.1 Tree SpacingGiza FirisaAinda não há avaliações

- Weekly Meal Planning and Selection and For Special OccasionDocumento6 páginasWeekly Meal Planning and Selection and For Special OccasionNhet Nhet Mercado100% (2)

- Mitchell, John, Educ 240, Health and Wellness Lesson PlansDocumento16 páginasMitchell, John, Educ 240, Health and Wellness Lesson Plansapi-277927821Ainda não há avaliações

- Keto Friendly Recipes: Easy Keto For Busy PeopleNo EverandKeto Friendly Recipes: Easy Keto For Busy PeopleNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2)

- Summary: Fast Like a Girl: A Woman’s Guide to Using the Healing Power of Fasting to Burn Fat, Boost Energy, and Balance Hormones: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNo EverandSummary: Fast Like a Girl: A Woman’s Guide to Using the Healing Power of Fasting to Burn Fat, Boost Energy, and Balance Hormones: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (2)

- Body Love Every Day: Choose Your Life-Changing 21-Day Path to Food FreedomNo EverandBody Love Every Day: Choose Your Life-Changing 21-Day Path to Food FreedomNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- The Diabetes Code: Prevent and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes NaturallyNo EverandThe Diabetes Code: Prevent and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes NaturallyNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Forever Strong: A New, Science-Based Strategy for Aging WellNo EverandForever Strong: A New, Science-Based Strategy for Aging WellAinda não há avaliações

- The Arm: Inside the Billion-Dollar Mystery of the Most Valuable Commodity in SportsNo EverandThe Arm: Inside the Billion-Dollar Mystery of the Most Valuable Commodity in SportsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (49)

- The Fast800 Diet: Discover the Ideal Fasting Formula to Shed Pounds, Fight Disease, and Boost Your Overall HealthNo EverandThe Fast800 Diet: Discover the Ideal Fasting Formula to Shed Pounds, Fight Disease, and Boost Your Overall HealthNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (37)

- Allen Carr's Easy Way for Women to Lose Weight: The original Easyway methodNo EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way for Women to Lose Weight: The original Easyway methodNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (18)

- Proteinaholic: How Our Obsession with Meat Is Killing Us and What We Can Do About ItNo EverandProteinaholic: How Our Obsession with Meat Is Killing Us and What We Can Do About ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (19)

- Glucose Goddess Method: A 4-Week Guide to Cutting Cravings, Getting Your Energy Back, and Feeling AmazingNo EverandGlucose Goddess Method: A 4-Week Guide to Cutting Cravings, Getting Your Energy Back, and Feeling AmazingNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (59)

- Happy Gut: The Cleansing Program to Help You Lose Weight, Gain Energy, and Eliminate PainNo EverandHappy Gut: The Cleansing Program to Help You Lose Weight, Gain Energy, and Eliminate PainNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (6)

- Hungry for Change: Ditch the Diets, Conquer the Cravings, and Eat Your Way to Lifelong HealthNo EverandHungry for Change: Ditch the Diets, Conquer the Cravings, and Eat Your Way to Lifelong HealthNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (7)

- Metabolism Revolution: Lose 14 Pounds in 14 Days and Keep It Off for LifeNo EverandMetabolism Revolution: Lose 14 Pounds in 14 Days and Keep It Off for LifeAinda não há avaliações

- Eat to Lose, Eat to Win: Your Grab-n-Go Action Plan for a Slimmer, Healthier YouNo EverandEat to Lose, Eat to Win: Your Grab-n-Go Action Plan for a Slimmer, Healthier YouAinda não há avaliações

- Instant Loss On a Budget: Super-Affordable Recipes for the Health-Conscious CookNo EverandInstant Loss On a Budget: Super-Affordable Recipes for the Health-Conscious CookNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2)

- Summary of Mary Claire Haver's The Galveston DietNo EverandSummary of Mary Claire Haver's The Galveston DietNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Rapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreNo EverandRapid Weight Loss Hypnosis: How to Lose Weight with Self-Hypnosis, Positive Affirmations, Guided Meditations, and Hypnotherapy to Stop Emotional Eating, Food Addiction, Binge Eating and MoreNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (17)

- How to Be Well: The 6 Keys to a Happy and Healthy LifeNo EverandHow to Be Well: The 6 Keys to a Happy and Healthy LifeNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- The Intuitive Eating Workbook: 10 Principles for Nourishing a Healthy Relationship with FoodNo EverandThe Intuitive Eating Workbook: 10 Principles for Nourishing a Healthy Relationship with FoodNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (20)

- Grit & Grace: Train the Mind, Train the Body, Own Your LifeNo EverandGrit & Grace: Train the Mind, Train the Body, Own Your LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (3)

- The Candida Cure: The 90-Day Program to Balance Your Gut, Beat Candida, and Restore Vibrant HealthNo EverandThe Candida Cure: The 90-Day Program to Balance Your Gut, Beat Candida, and Restore Vibrant HealthAinda não há avaliações

- Lose Weight by Eating: 130 Amazing Clean-Eating Makeovers for Guilt-Free Comfort FoodNo EverandLose Weight by Eating: 130 Amazing Clean-Eating Makeovers for Guilt-Free Comfort FoodNota: 2 de 5 estrelas2/5 (1)

- The Whole Body Reset: Your Weight-Loss Plan for a Flat Belly, Optimum Health & a Body You'll Love at Midlife and BeyondNo EverandThe Whole Body Reset: Your Weight-Loss Plan for a Flat Belly, Optimum Health & a Body You'll Love at Midlife and BeyondNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (28)

- The Raw Food Detox Diet: The Five-Step Plan for Vibrant Health and Maximum Weight LossNo EverandThe Raw Food Detox Diet: The Five-Step Plan for Vibrant Health and Maximum Weight LossNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (22)

- Power Souping: 3-Day Detox, 3-Week Weight-Loss PlanNo EverandPower Souping: 3-Day Detox, 3-Week Weight-Loss PlanNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)

- The Toxin Solution: How Hidden Poisons in the Air, Water, Food, and Products We Use Are Destroying Our Health—AND WHAT WE CAN DO TO FIX ITNo EverandThe Toxin Solution: How Hidden Poisons in the Air, Water, Food, and Products We Use Are Destroying Our Health—AND WHAT WE CAN DO TO FIX ITNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Kintsugi Wellness: The Japanese Art of Nourishing Mind, Body, and SpiritNo EverandKintsugi Wellness: The Japanese Art of Nourishing Mind, Body, and SpiritNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)

- Think Yourself Thin: A 30-Day Guide to Permanent Weight LossNo EverandThink Yourself Thin: A 30-Day Guide to Permanent Weight LossNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (22)