Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Analysing and Presenting Qualitative Data

Enviado por

AishaDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Analysing and Presenting Qualitative Data

Enviado por

AishaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Analysing and presenting IN BRIEF

• Analysing and presenting qualitative data

qualitative data is one of the most confusing aspects of

PRACTICE

qualitative research.

• This paper provides a pragmatic approach

using a form of thematic content

P. Burnard,1 P. Gill,2 K. Stewart,3 E. Treasure4 and B. Chadwick5 analysis. Approaches to presenting

qualitative data are also discussed.

• The process of qualitative data analysis

is labour intensive and time consuming.

Those who are unsure about this

approach should seek appropriate advice.

This paper provides a pragmatic approach to analysing qualitative data, using actual data from a qualitative dental public

health study for demonstration purposes. The paper also critically explores how computers can be used to facilitate this

process, the debate about the verification (validation) of qualitative analyses and how to write up and present qualitative

research studies.

INTRODUCTION

APPROACHES TO ANALYSING framework and uses the actual data

QUALITATIVE DATA

Previous papers in this series have intro itself to derive the structure of analy

duced readers to qualitative research There are two fundamental approaches sis. This approach is comprehensive and

and identified approaches to collecting to analysing qualitative data (although therefore time-consuming and is most

qualitative data. However, for those new each can be handled in a variety of dif suitable where little or nothing is known

to this approach, one of the most bewil ferent ways): the deductive approach about the study phenomenon. Inductive

dering aspects of qualitative research and the inductive approach.1,2 Deductive analysis is the most common approach

is, perhaps, how to analyse and present approaches involve using a structure or used to analyse qualitative data2 and is,

the data once it has been collected. This predetermined framework to analyse therefore, the focus of this paper.

final paper therefore considers a method data. Essentially, the researcher imposes Whilst a variety of inductive

of analysing and presenting textual data their own structure or theories on the approaches to analysing qualitative data

gathered during qualitative work. data and then uses these to analyse the are available, the method of analysis

interview transcripts.3 described in this paper is that of thematic

This approach is useful in studies content analysis, and is, perhaps, the

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH where researchers are already aware most common method of data analysis

IN DENTISTRY of probable participant responses. For used in qualitative work.4,5 This method

example, if a study explored patients’ arose out of the approach known as

1. Qualitative research in dentistry

reasons for complaining about their grounded theory,6 although the method

2. Methods of data collection in qualitative

research: interviews and focus groups dentist, the interview may explore com can be used in a range of other types of

3. Conducting qualitative interviews with mon reasons for patients’ complaints, qualitative work, including ethnography

school children in dental research such as trauma following treatment and phenomenology (see the fi rst paper

4. Analysing and presenting qualitative data and communication problems. The data in this series7 for defi nitions). Indeed,

analysis would then consist of exam the process of thematic content analy

ining each interview to determine how sis is often very similar in all types of

many patients had complaints of each qualitative research, in that the process

1

Professor of Nursing, Cardiff School of Nursing type and the extent to which complaints involves analysing transcripts, identify

and Midwifery Studies, Ty Dewi Sant, Heath Park,

Cardiff, CF14 4XY; 2* Senior Research Fellow, Faculty of

of each type co-occur.3 However, while ing themes within those data and gath

Health, Sport and Science, University of Glamorgan, this approach is relatively quick and ering together examples of those themes

Pontypridd, CF37 1DL; 3Research Fellow, Academic Unit

of Primary Care, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 2AA

easy, it is inflexible and can potentially from the text.

4

Dean, School of Dentistry/Professor of Dental Public bias the whole analysis process as the

Health, 5Professor of Paediatric Dentistry, Dental Health

coding framework has been decided in DATA COLLECTION

and Biological Sciences, School of Dentistry, Cardiff

University, Heath Park, Cardiff, CF14 4XY advance, which can severely limit theme

AND DATA ANALYSIS

*Correspondence to: Dr Paul Gill

Email: PWGill@glam.ac.uk

and theory development. Interview transcripts, field notes and

Conversely, the inductive approach observations provide a descriptive

Refereed Paper

DOI: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

involves analysing data with little or account of the study, but they do not pro

© British Dental Journal 2008; 204: 429-432 no predetermined theory, structure or vide explanations.4 It is the researcher

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 204 NO. 8 APR 26 2008 429

© 2008 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

who has to make sense of the data that

have been collected by exploring and Table 1 An example of an initial coding framework

interpreting them.

Interview transcript Initial coding framework

Quantitative and qualitative research

differ somewhat in their approach to Interviewer: ‘Can you tell me about what you like to eat?’

data analysis. In quantitative research,

Child: ‘I like crisps, chips, sweets. I like sweets and chocolate

data analysis often only occurs after the most. I like apples, grapes and oranges. Oh and pizza, Food preferences

all or much of data have been collected. I really like pizza.’

However, in qualitative research, data

Interviewer: ‘What do you like about those things?’

analysis often begins during, or imme

diately after, the first data are collected, Child: ‘…Well the apples and the other fruit I just really like Food preferences

although this process continues and is the taste and they are healthy I suppose. We eat those in Healthy foods

modified throughout the study. Initial school now and my friends like them, so I eat them with Food choices in school

my friends. Peer influence

analysis of the data may also further ‘I really like sweets and chocolates though, they are my

inform subsequent data collection. For favourites but I know they aren’t really good for you. If you Effects of sweets and chocolate

example, interview schedules may be eat too many they can be bad for your teeth. They can make

them go brown or drop out.’

slightly modified in light of emerging

findings, where additional clarification

may be required. Table 2 An example of a final coding framework after reduction of the categories

in the initial coding framework

Computer software for Final coding framework Initial coding framework

data analysis

• Perceptions of food

The method of analysis described in this • Positive notions of food and consequences

1. Contrasts and contradictions

paper involves managing the data ‘by • Negative notions of food and consequences

hand’. However, there are several com • Healthy/unhealthy foods

puter-assisted qualitative data analysis • Peer influence

software (CAQDAS) packages available 2. Copying friends • Copying

that can be used to manage and help in • Food choices in school

• Food choices and preferences of friendship groups

the analysis of qualitative data. Com

mon programmes include ATLAS. ti and • Diet in childhood

NVivo. It should be noted, however, that

• Food preferences

3. Diet in adulthood and childhood • Expected diet as a ‘grown up’

such programs do not ‘analyse’ the data • Perceptions of adult/child diets

– that is the task of the researcher – they • The need to be ‘healthy’ as an adult

simply manage the data and make han • Effects of sweets and chocolates

dling of them easier. 4. Single item consequences • Effects of ‘junk food’

For example, computer packages can

• Effects of fizzy drinks

help to manage, sort and organise large

volumes of qualitative data, store, anno discovering themes in the interview are deviations) can simply be uncoded.

tate and retrieve text, locate words, transcripts and attempting to verify, Such ‘off the topic’ material is sometimes

phrases and segments of data, prepare confirm and qualify them by search known as ‘dross’.9

diagrams and extract quotes.8 However, ing through the data and repeating the Table 1 is an example of the initial

whilst computer programmes can facili process to identify further themes and coding framework used in the data gen

tate data analysis, making the proc categories.4 erated from an actual interview with

ess easier and, arguably, more flexible, In order to do this, once the inter a child in a qualitative dental public

accurate and comprehensive, they do not views have been transcribed verbatim, health study, exploring primary school

confirm or deny the scientific value or the researcher reads each transcript and children’s understanding of food.10

quality of qualitative research, as they makes notes in the margins of words, In the second stage, the researcher

are merely instruments, as good or as theories or short phrases that sum up collects together all of the words and

bad as the researcher using them. what is being said in the text. This is phrases from all of the interviews onto

usually known as open coding. The aim, a clean set of pages. These can then be

Stages in the process however, is to offer a summary state worked through and all duplications

Regardless of whether data are analysed ment or word for each element that is crossed out. This will have the effect

by hand or using computer software, the discussed in the transcript. The excep of reducing the numbers of ‘categories’

process of thematic content analysis is tion to this is when the respondent has quite considerably.11,12 Using a section of

essentially the same, in that it involves clearly gone off track and begun to move the initial coding framework from the

identifying themes and categories that away from the topic under discussion. above study,10 such a list of categories

‘emerge from the data’. This involves Such deviations (as long as they really might read as follows:

430 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 204 NO. 8 APR 26 2008

© 2008 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

• Children’s perception of food However, researchers wishing to use such health, and perhaps even as a result of

• Positive notions of food and their software should first undertake appro- participation in the study.15

consequences priate training and should be aware that Some respondents may also want to

• Negative notions of food and their most programmes often do not abide by modify their opinions on re-presenta

consequences normal MS Windows conventions (eg, tion of the data if they now feel that, on

• Peer influence most interview transcripts have to be reflection, their original comments are

• Copying converted from MS Word into rich text not ‘socially desirable’. There is also the

• Healthy/unhealthy foods format before they can be imported into problem of how to present such informa

• Effects of sweets and chocolates the programme for analysis). tion to people who are likely to be non

• Effects of ‘junk food’ academics. Furthermore, it is possible

• Food choices in school Verification that some participants will not recognise

• Diet in childhood The analysis of qualitative data does, of some of the emerging theories, as each

• Food preferences course, involve interpreting the study of them will probably have contributed

• Expected diet as a ‘grown up’ findings. However, this process is argu only a portion of the data.16

• Food choices and preferences of ably more subjective than the process The process of peer review involves

friendship groups normally associated with quantitative at least one other suitably experienced

• Effects of fi zzy drinks data analysis, since a common belief researcher independently reviewing

• Perceptions of adult/child diets amongst social scientists is that a defi ni and exploring interview transcripts,

• The need to be ‘healthy’ as an adult. tive, objective view of social reality does data analysis and emerging themes. It

not exist. For example, some quantita has been argued that this process may

Once this second, shorter list of cate tive researchers claim that qualitative help to guard against the potential for

gories has been compiled, the researcher accounts cannot be held straightfor lone researcher bias and help to provide

goes a stage further and looks for over wardly to represent the social world, additional insights into theme and the

lapping or similar categories. Informed thus different researchers may interpret ory development.14,16,17 However, many

by the analytical and theoretical ideas the same data somewhat differently.4 researchers also feel that the value of

developed during the research, these cat Consequently, this leads to the issue of this approach is questionable, since it is

egories are further refined and reduced the verifiability of qualitative data anal possible that each researcher may inter

in number by grouping them together.4 ysis. pret the data, or parts of it, differently.8

A list of several categories (perhaps up to There is, therefore, a debate as to Also, if both perspectives are grounded

a maximum of twelve) can then be com whether qualitative researchers should in and supported by the data, is one

piled. If we consider the above example, have their analyses verified or validated interpretation necessarily stronger or

we might eventually come up with the by a third party.13,14 It has been argued more valid than the other?

reduced list shown in Table 2. that this process can make the analysis Unfortunately, despite perpetual

This reduced list forms the fi nal cat more rigorous and reduce the element debate, there is no definitive answer to

egory system that can be used to divide bias. There are two key ways of hav the issue of validity in qualitative analy

up all of the interviews.12 The next stage ing data analyses validated by others: sis. However, to ensure that the analysis

is to allocate each of the categories its respondent validation (or member check) process is systematic and rigorous, the

own coloured marking pen and then – returning to the study participants and whole corpus of collected data must be

each transcript is worked through and asking them to validate analyses – and thoroughly analysed. Therefore, where

data that fit under a particular category peer review (or peer debrief, also referred appropriate, this should also include the

are marked with the according col to as inter-rater reliability) – whereby search for and identification of relevant

our. Finally, all of the sections of data, another qualitative researcher analyses ‘deviant or contrary cases’ – ie, fi nd

under each of the categories (and thus the data independently.13-15 ings that are different or contrary to the

assigned a particular colour) are cut out Participant validation involves return main findings, or are simply unique to

and pasted onto the A4 sheets. Subject ing to respondents and asking them to some or even just one respondent. Quali

dividers can then be labelled with each carefully read through their interview tative researchers should also utilise a

category label and the corresponding transcripts and/or data analysis for process of ‘constant comparison’ when

coloured snippets, on each of the pages, them to validate, or refute, the research analysing data. This essentially involves

are filed in a lever arch file. What the er’s interpretation of the data. Whilst reading and re-reading data to search

researcher has achieved is an organised this can arguably help to refi ne theme for and identify emerging themes in

dataset, filed in one folder. It is from this and theory development, the process is the constant search for understanding

folder that the report of the fi ndings can hugely time consuming and, if it does and the meaning of the data.18,19 Where

be written. not occur relatively soon after data col appropriate, researchers should also pro

As discussed earlier, computer pro lection and analysis, participants may vide a detailed explication in published

grammes can be used to manage this have also changed their perceptions reports of how data was collected and

process and may be particularly useful in and views because of temporal effects analysed, as this helps the reader to crit

qualitative studies with larger datasets. and potential changes in their situation, ically assess the value of the study.

BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 204 NO. 8 APR 26 2008 431

© 2008 Nature Publishing Group

PRACTICE

It should also be noted that qualitative these supporting chapters would also undertaking this process for the fi rst

data cannot be usefully quantified given be used to develop theories or hypoth- time, we recommend seeking advice from

the nature, composition and size of the esise about the data and, if appropri experienced qualitative researchers.

sample group, and ultimately the episte ate, to make realistic conclusions and

1. Spencer L, Ritchie J, O’Connor W. Analysis: prac

mological aim of the methodology. recommendations for practice and tices, principles and processes. In Ritchie J, Lewis

further research. J (eds) Qualitative research practice. pp 199-218.

WRITING AND PRESENTING London: Sage Publications, 2004.

2. Lathlean J. Qualitative analysis. In Gerrish K, Lacy

QUALITATIVE RESEARCH Example b (combined findings A (eds) The research process in nursing. pp 417

There are two main approaches to

and discussion chapter): 433. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2006.

3. Williams C, Bower E J, Newton J T. Research in

writing up the fi ndings of qualitative Copying friends primary dental care part 6: data analysis. Br Dent J

2004; 197: 67-73.

research.20 The first is to simply report In this study, as with others (eg Lud 4. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Analysing qualitative

key findings under each main theme or vigsen & Sharma21 and Watt & Shei data. In Pope C, Mays N (eds) Qualitative research

in health care. 2nd ed. pp 75-88. London: BMJ

category, using appropriate verbatim ham22), peer influence is a strong factor, Books, 1999.

quotes to illustrate those fi ndings. This is with children copying each other’s food 5. Ritchie J, Spencer L, O’Connor W. Carrying out

qualitative analysis. In Ritchie J, Lewis J (eds)

then accompanied by a linking, separate choices at school meal times: Qualitative research practice. pp 219-262. London:

discussion chapter in which the fi nd Girl: ‘They say “copy me and what I Sage Publications, 2004.

6. Glaser B G, Strauss A L. The discovery of grounded

ings are discussed in relation to existing have.”’ theory: strategies for qualitative research. Chicago:

research (as in quantitative studies). The Interviewer: ‘And do you copy them if Aldine Publishing Company, 1967.

7. Stewart K, Gill P, Chadwick B, Treasure E. Qualita

second is to do the same but to incor they say that?’ tive research in dentistry. Br Dent J 2008; 204:

porate the discussion into the fi ndings Girl: ‘Yes.’ 235-239.

8. Seale C. Analysing your data. In Silverman D (ed)

chapter. Below are brief examples of the Interviewer: ‘Why do you copy them if Doing qualitative research. pp 154-174. London:

two approaches, using actual data from they say that?’ Sage Publications, 2000.

9. Morse J M, Field P. Nursing research: the applica

a qualitative dental public health study Girl: ‘Because they are my friends.’ tion of qualitative approaches. Cheltenham:

that explored primary school children’s (Girl, school 1, age 7). Stanley Thornes, 1996.

10. Stewart K, Gill P, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Under

understanding of food.10 Children also identified friendship standing about food among 6-11 year olds in

groups according to the school meal type South Wales. Food Cult Soc 2006; 9: 317-333.

Example a (the they have. Children have been known to

11. Burnard P. A method of analysing interview tran

scripts in qualitative research. Nurse Educ Today

traditional approach): have school dinners, or packed lunches 1991; 11: 461-466.

12. Burnard P. A pragmatic approach to qualita

FINDINGS if their friends also have the same.21 tive data analysis. In Newell R, Burnard P (eds).

Contrasts and contradictions Research for evidence based practice. pp 97-107.

Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

The interviews demonstrated that chil If this approach was used, the com 13. Mays N, Pope C. Rigour and qualitative research.

dren are able to operate contrasts and bined findings and discussion section BMJ 1995; 311: 109-112.

14. Barbour R S. Checklists for improving rigour in

contradictions about food effortlessly. would simply be followed by a conclud qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the

These contradictions are both sophisti ing chapter. Further guidance on writ dog? BMJ 2001; 322: 1115-1117.

15. Long T, Johnson M. Rigour, reliability and validity

cated and complex, incorporating posi ing up qualitative reports can be found in qualitative research. Clin Eff Nurs 2000;

tive and negative notions relating to in the literature.20 4: 30-37.

16. Cutcliffe J R, McKenna H P. Establishing the cred

food and its health and social conse ibility of qualitative research findings: the plot

quences, which they are able to fluently CONCLUSION thickens. J Adv Nurs 1999; 30: 374-380.

17. Andrews M, Lyne P, Riley E. Validity in qualitative

adopt when talking about food: This paper has described a pragmatic health care research: an exploration of the impact

‘My mother says drink juice because it’s process of thematic content analysis as of individual researcher perspectives within col

laborative enquiry. J Adv Nurs 1996; 23: 441-447.

healthy and she says if you don’t drink it a method of analysing qualitative data 18. Silverman D. Doing qualitative research. London:

you won’t get healthy and you won’t have generated by interviews or focus groups. Sage Publications, 2000.

19. Polit D F, Beck C T. Essentials of nursing research:

any sweets and you’ll end up having to go Other approaches to analysis are avail methods, appraisal, and utilization. 6th ed. Phila

to hospital if you don’t eat anything like able and are discussed in the literature.23 delphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

25 20. Burnard P. Writing a qualitative research report.

vegetables because you’ll get weak’. (Girl, The method described here offers a Nurse Educ Today 2004; 24: 174-179.

school 3, age 11 years). method of generating categories under 21. Ludvigsen A, Sharma N. Burger boy and sporty girl;

children and young people’s attitudes towards food

which similar themes or categories can be in school. Barkingside: Barnardo’s, 2004.

If this approach was used, the fi ndings collated. The paper also briefly illustrates 22. Watt R G, Sheiham A. Towards an understanding

of young people’s conceptualisation of food and

chapter would subsequently be followed two different ways of presenting qualita eating. Health Educ J 1997; 56: 340-349.

by a separate supporting discussion and tive reports, having analysed the data. 23. Bryman A, Burgess R (eds). Analysing qualitative

data. London: Routledge, 1993.

conclusion section in which the fi nd This analysis process, when done 24. Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis.

ings would be critically discussed and properly, is systematic and rigorous 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1994.

25. Silverman D. Interpreting qualitative data: methods

compared to the appropriate existing and therefore labour-intensive and time for analysing talk, text and interaction. 3rd ed.

research. As in quantitative research, consuming.4 Consequently, for those Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 2006.

432 BRITISH DENTAL JOURNAL VOLUME 204 NO. 8 APR 26 2008

© 2008 Nature Publishing Group

Você também pode gostar

- Methods of Data Collection in Qualitative Research - Interviews and Focus Group PDFDocumento5 páginasMethods of Data Collection in Qualitative Research - Interviews and Focus Group PDFRianaDyahPrameswariAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 15 - Analyzing Qualitative DataDocumento8 páginasChapter 15 - Analyzing Qualitative Datajucar fernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Development of Questionnaires for Quantitative Medical ResearchNo EverandDevelopment of Questionnaires for Quantitative Medical ResearchAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Research for Beginners: From Theory to PracticeNo EverandQualitative Research for Beginners: From Theory to PracticeNota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (2)

- Modern Research Design: The Best Approach To Qualitative And Quantitative DataNo EverandModern Research Design: The Best Approach To Qualitative And Quantitative DataAinda não há avaliações

- A Step-By-Step Guide to Questionnaire Validation ResearchNo EverandA Step-By-Step Guide to Questionnaire Validation ResearchAinda não há avaliações

- Analyzing Qualitative DataDocumento8 páginasAnalyzing Qualitative DataLilianaAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Research DesignsDocumento82 páginasQualitative Research DesignsKmerylEAinda não há avaliações

- Learning Differences and Pedagogy Assessment 1Documento4 páginasLearning Differences and Pedagogy Assessment 1api-286010396Ainda não há avaliações

- DMS & DPCS Research MethodsDocumento35 páginasDMS & DPCS Research MethodsMr DamphaAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 5: Qualitative ResearchDocumento17 páginasAssignment 5: Qualitative Researchbrunooliveira_tkd2694Ainda não há avaliações

- Research Methodology ChapterDocumento5 páginasResearch Methodology ChapterBinayKPAinda não há avaliações

- Conducting Thematic Analysis With Qualitative DataDocumento18 páginasConducting Thematic Analysis With Qualitative DataChiagozie EneAinda não há avaliações

- Research ApproachesDocumento13 páginasResearch ApproachesBernard WashingtonAinda não há avaliações

- Ethics, Qualitative And Quantitative Methods In Public Health ResearchNo EverandEthics, Qualitative And Quantitative Methods In Public Health ResearchAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Methods Workshop - MurrayDocumento33 páginasQualitative Methods Workshop - MurrayRyaandavisAinda não há avaliações

- A3 Research Proposal Example 1Documento20 páginasA3 Research Proposal Example 1Nishu JainAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Research: Company LogoDocumento7 páginasQualitative Research: Company Logosordy mahusay mingasca100% (4)

- Triangulation Research MethodDocumento11 páginasTriangulation Research MethodWati LkrAinda não há avaliações

- Chittagong University Social Science Research Institute (SSRI) Training Workshop On Research Methodology 5-7 October 2015Documento21 páginasChittagong University Social Science Research Institute (SSRI) Training Workshop On Research Methodology 5-7 October 2015Badsha MiaAinda não há avaliações

- A Guide To Writing Policy Briefs For Research UptakeDocumento17 páginasA Guide To Writing Policy Briefs For Research UptakeRebecca WolfeAinda não há avaliações

- Community Health WorkersDocumento42 páginasCommunity Health WorkersSathya PalanisamyAinda não há avaliações

- Week4 Qualitative Methods Data Collection TechniquesDocumento22 páginasWeek4 Qualitative Methods Data Collection TechniquesYamith J. FandiñoAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Research MethodsDocumento21 páginasQualitative Research MethodsDianneGarcia100% (2)

- SyllabusDocumento4 páginasSyllabus陈杰Ainda não há avaliações

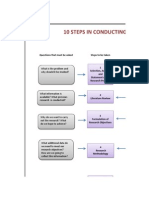

- 10 Steps in Conducting Research: Questions That Must Be Asked Steps To Be TakenDocumento6 páginas10 Steps in Conducting Research: Questions That Must Be Asked Steps To Be TakenNarendra VaidyaAinda não há avaliações

- Criteria For Evaluation Qual ResearchDocumento6 páginasCriteria For Evaluation Qual ResearchElsiechAinda não há avaliações

- Data Coding and Screening: Jessica True Mike Cendejas Krystal Appiah Amy Guy Rachel PacasDocumento43 páginasData Coding and Screening: Jessica True Mike Cendejas Krystal Appiah Amy Guy Rachel PacassrirammaliAinda não há avaliações

- Kpolovie and Obilor PDFDocumento26 páginasKpolovie and Obilor PDFMandalikaAinda não há avaliações

- MAPP Field Guide Focus Group StepsDocumento1 páginaMAPP Field Guide Focus Group StepsJamie ZimmermanAinda não há avaliações

- ResumeDocumento2 páginasResumeapi-283008119Ainda não há avaliações

- Guidebook For Social Work Literature Reviews and Research Questions 1612823100. - PrintDocumento138 páginasGuidebook For Social Work Literature Reviews and Research Questions 1612823100. - PrintSunshine CupoAinda não há avaliações

- Getting Qualitative Research PublishedDocumento9 páginasGetting Qualitative Research PublishedNadji ChiAinda não há avaliações

- The Steps of Qualitative Data AnalysisDocumento92 páginasThe Steps of Qualitative Data AnalysisEmmanuel MichaelAinda não há avaliações

- Research ProposalDocumento12 páginasResearch Proposalumar2040Ainda não há avaliações

- Characteristics of Qualitative ResearchDocumento7 páginasCharacteristics of Qualitative ResearchDodong PantinopleAinda não há avaliações

- Data Collection Is An Important Aspect of Any Type of Research StudyDocumento20 páginasData Collection Is An Important Aspect of Any Type of Research Studykartikeya10Ainda não há avaliações

- Pivot Data Design-Jennifer NultyDocumento11 páginasPivot Data Design-Jennifer Nultyapi-314439984Ainda não há avaliações

- The Pragmatic Research Approach - A Framework For Sustainable Management of Public Housing Estates in NigeriaDocumento12 páginasThe Pragmatic Research Approach - A Framework For Sustainable Management of Public Housing Estates in NigeriaAdministrationdavid100% (1)

- UNICEF Childhood Disability in MalaysiaDocumento140 páginasUNICEF Childhood Disability in Malaysiaying reenAinda não há avaliações

- Research Proposal SummaryDocumento24 páginasResearch Proposal SummaryFitri Siburian0% (1)

- S 529 Bibliography 1Documento18 páginasS 529 Bibliography 1Gabriel AnriquezAinda não há avaliações

- The Qualitative Research ProposalDocumento11 páginasThe Qualitative Research Proposalanisatun nikmah0% (1)

- NJC - Toolkit - Critiquing A Quantitative Research ArticleDocumento12 páginasNJC - Toolkit - Critiquing A Quantitative Research ArticleHeather Carter-Templeton100% (1)

- Focus Group GuideDocumento12 páginasFocus Group GuideKamlesh SoniwalAinda não há avaliações

- Research Methods Information BookletDocumento18 páginasResearch Methods Information Bookletapi-280673736Ainda não há avaliações

- Participatory Micro-PlanningDocumento39 páginasParticipatory Micro-PlanningSheikh Areeba100% (1)

- Review of Case Study Research BookDocumento19 páginasReview of Case Study Research BookDEWI WAHYU HANDAYANI (023865)Ainda não há avaliações

- Predispositions of Quantitative and Qualitative Modes of InquiryDocumento4 páginasPredispositions of Quantitative and Qualitative Modes of Inquirykinhai_see100% (1)

- @final Dissertation PDFDocumento69 páginas@final Dissertation PDFT.Wai NgAinda não há avaliações

- Topic 2 DQ 1 2Documento3 páginasTopic 2 DQ 1 2BettAinda não há avaliações

- Methods of ResearchDocumento5 páginasMethods of Researchanon_794869624Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4: Analyzing Qualitative DataDocumento16 páginasChapter 4: Analyzing Qualitative DataKirui Bore PaulAinda não há avaliações

- Research MethodologyDocumento20 páginasResearch Methodologytumusiime isaacAinda não há avaliações

- Research on English Language Teaching: Collecting Qualitative DataDocumento38 páginasResearch on English Language Teaching: Collecting Qualitative DataAyu Wsr100% (1)

- Inclusive Education Assessemnt 2Documento12 páginasInclusive Education Assessemnt 2api-435774579Ainda não há avaliações

- Choosing A Research MethodDocumento26 páginasChoosing A Research MethodmckohimaAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Versus Quantitative ResearchDocumento18 páginasQualitative Versus Quantitative ResearchShreyansh PriyamAinda não há avaliações

- FiguresDocumento43 páginasFiguresAishaAinda não há avaliações

- Strategic Planning:-: 1. It Allows Organizations To Be Proactive Rather Than ReactiveDocumento6 páginasStrategic Planning:-: 1. It Allows Organizations To Be Proactive Rather Than ReactiveAishaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1Documento28 páginasChapter 1AishaAinda não há avaliações

- High Performance Work SystemsDocumento4 páginasHigh Performance Work SystemsAishaAinda não há avaliações

- What Is EEO?: Enforcing The LawDocumento5 páginasWhat Is EEO?: Enforcing The LawAishaAinda não há avaliações

- HRRMMMDocumento40 páginasHRRMMMAishaAinda não há avaliações

- What Is EEO?: Enforcing The LawDocumento5 páginasWhat Is EEO?: Enforcing The LawAishaAinda não há avaliações

- Ipa 23Documento62 páginasIpa 23AishaAinda não há avaliações

- 10 - Chapter 1 PDFDocumento33 páginas10 - Chapter 1 PDFHarbrinder GurmAinda não há avaliações

- Qualitative Research: Sampling & Sample Size Considerations: Study NotesDocumento6 páginasQualitative Research: Sampling & Sample Size Considerations: Study NotesAishaAinda não há avaliações

- Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocumento4 páginasCorporate Social ResponsibilityAishaAinda não há avaliações

- 30 Day Ketogenic Diet Plan v2Documento13 páginas30 Day Ketogenic Diet Plan v2AishaAinda não há avaliações

- A Practical Guide To Using Interpretativ PDFDocumento8 páginasA Practical Guide To Using Interpretativ PDFgatoitoAinda não há avaliações

- David Evans, Paul Gruba, Justin Zobel (Auth.) - How To Write A Better Thesis-Springer International Publishing (2014)Documento63 páginasDavid Evans, Paul Gruba, Justin Zobel (Auth.) - How To Write A Better Thesis-Springer International Publishing (2014)AishaAinda não há avaliações

- 30 Day Ketogenic Diet Plan v2 PDFDocumento93 páginas30 Day Ketogenic Diet Plan v2 PDFdevilcaeser2010100% (2)

- Small Business GuideDocumento53 páginasSmall Business GuideadnanAinda não há avaliações

- 2011 Q 3 Business ModelingDocumento12 páginas2011 Q 3 Business ModelingAishaAinda não há avaliações

- Matlab Cheat Sheet PDFDocumento3 páginasMatlab Cheat Sheet PDFKarishmaAinda não há avaliações

- Group 5 Road To Success!Documento19 páginasGroup 5 Road To Success!Nicole EspinoAinda não há avaliações

- Malhotra MR6e 01Documento28 páginasMalhotra MR6e 01Tabish BhatAinda não há avaliações

- Logistic Regression Using SASDocumento22 páginasLogistic Regression Using SASSubhashish SarkarAinda não há avaliações

- 100 years of tailings dam failure data insightsDocumento7 páginas100 years of tailings dam failure data insightsGonzalo Villouta StenglAinda não há avaliações

- Ubc 2020 May Robertson RebeccaDocumento189 páginasUbc 2020 May Robertson RebeccaThato KeteloAinda não há avaliações

- Sample-Chapter-3-METHODOLOGYDocumento20 páginasSample-Chapter-3-METHODOLOGYlukezedryll15Ainda não há avaliações

- 3 CPA QUANTITATIVE TECHNIQUES Paper 3Documento8 páginas3 CPA QUANTITATIVE TECHNIQUES Paper 3Nanteza SharonAinda não há avaliações

- Defining Research Problem and Research DesignDocumento16 páginasDefining Research Problem and Research Designjerry elizagaAinda não há avaliações

- JP 2-0 Joint IntelligenceDocumento150 páginasJP 2-0 Joint Intelligenceshakes21778Ainda não há avaliações

- Research Title: Development-Induced Displacement: A Case Study of Sardar Sarovar Project and Tribal Rehabilitation of Nandurbar District of MaharashtraDocumento6 páginasResearch Title: Development-Induced Displacement: A Case Study of Sardar Sarovar Project and Tribal Rehabilitation of Nandurbar District of MaharashtraShaki KopareAinda não há avaliações

- HND Level 5 Business (Management) - Unit 17 Assignment Brief Sept 2018Documento7 páginasHND Level 5 Business (Management) - Unit 17 Assignment Brief Sept 2018Shaji Viswanathan. Mcom, MBA (U.K)100% (1)

- GMP Quality Assurance ProceduresDocumento22 páginasGMP Quality Assurance ProceduresLen Surban100% (1)

- An Empirical Study of Employee Loyalty, Service Quality and Firm Performance in The Service IndustryDocumento12 páginasAn Empirical Study of Employee Loyalty, Service Quality and Firm Performance in The Service IndustryKazim NaqviAinda não há avaliações

- Morales 2019Documento6 páginasMorales 2019signif newsAinda não há avaliações

- She's Yours For The TakingDocumento281 páginasShe's Yours For The TakingMichel Aus Lönneberga75% (8)

- Forensic Science International: ReportsDocumento10 páginasForensic Science International: ReportsSekarSukomasajiAinda não há avaliações

- English Kannada DictionaryDocumento89 páginasEnglish Kannada DictionaryBhujabali BogarAinda não há avaliações

- 10 1108 - Ijppm 02 2017 0037 PDFDocumento22 páginas10 1108 - Ijppm 02 2017 0037 PDFJennyfer ValenzuelaAinda não há avaliações

- Data-Informed Community-Focused Policing: in The Los Angeles Police DepartmentDocumento27 páginasData-Informed Community-Focused Policing: in The Los Angeles Police DepartmentJake LanceAinda não há avaliações

- Assessment 1 SyllabusDocumento10 páginasAssessment 1 SyllabusSheila Posas100% (1)

- ARTICLE, 2002 - Causes-of-Construction-DelayDocumento7 páginasARTICLE, 2002 - Causes-of-Construction-Delayb165Ainda não há avaliações

- LINIEARITYDocumento14 páginasLINIEARITYazadsingh1Ainda não há avaliações

- 5 APQP 1 of 3Documento3 páginas5 APQP 1 of 3P G SumanAinda não há avaliações

- Amazon's Success Through InnovationDocumento17 páginasAmazon's Success Through InnovationMmc Mix100% (1)

- Adherence QuestionnaireDocumento8 páginasAdherence QuestionnaireDhila FayaAinda não há avaliações

- DSWD Research Request FormDocumento4 páginasDSWD Research Request Formmichael tampusAinda não há avaliações

- Mediation and Multi-Group ModerationDocumento41 páginasMediation and Multi-Group ModerationdongAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Consumer Preferences for Wristwatch AttributesDocumento44 páginasUnderstanding Consumer Preferences for Wristwatch AttributesKarthikeyan NAinda não há avaliações

- The Influence of Electronic Tax Filing SDocumento24 páginasThe Influence of Electronic Tax Filing SAberaAinda não há avaliações