Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Law Reading

Enviado por

Donna Jane SimeonDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Law Reading

Enviado por

Donna Jane SimeonDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Today is Saturday, February 09, 2019

Custom Search

ances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL Exclusive

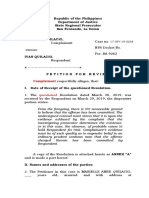

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

G.R. Nos. 80315-16 November 16, 1994

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

JOEL QUINTERO Y YBASCO, accused-appellant.

The Solicitor General for plaintiff-appellee.

Public Attorney's Office for accused-appellant.

BELLOSILLO, J.:

JOEL QUINTERO Y YBASCO is languishing in the Maximum Security

Compound at the New Bilibid Prisons in Muntinlupa, Metro Manila,

because the prosecution witnesses, according to the court a quo, were

more credible than the accused. Since a criminal prosecution involves not

only the question of credibility but the more important issue of whether the

guilt of the accused has been established beyond reasonable doubt, we

are inevitably drawn to a verdict of acquittal.

The version of the prosecution is that on 19 March 1986 Pfc. Emeterio

Malanyaon of the Anti-Narcotics Section, Makati Police Station, received

a telephone call from an unidentified woman informer that a man dressed

in white T-shirt, khaki shorts and tennis shoes was selling shabu at

P10.00 per foil along Pateros St., Makati. To check the veracity of the call,

the woman was requested to call again in the afternoon, which she did,

and affirmed her earlier report. Thereafter, a team composed of Pfc.

Henry de la Cruz, Det. Emeterio Malanyaon, Det. Marlon Almoguerra,

Det. Antonio Manalastas, and Dets. Del Prado and Dionida (their first

names not given in the record) proceeded to Pateros St. on a buy-bust

operation. The informant was not with the team. While Det. Almoguerra

posed as buyer, Dets. Malanyaon and Dionida acted as peanut and corn

vendors, respectively. The rest of them posted themselves some fifteen

(15) meters away from where the accused sat in front of a sari-sari store.

The prosecution further narrates that the accused approached Det.

Almoguerra and asked, "P're, score ka ba?" Thereafter, an exchange of

one foil of marijuana and a marked P10.00-bill ensued. The accused was

then arrested and frisked as a result of which nine (9) more foils of dried

marijuana leaves and eleven (11) sticks of marijuana cigarettes were

recovered from his waistline. He was brought to the Makati Police Station

where he executed a written statement (Exh. "A") admitting possession of

more prohibited drugs in his house at Pateros St. and requesting the buy-

bust team to accompany him there in order to get the drugs. On the basis

of the confession, six (6) more plastic bags containing dried marijuana

flowering tops and another bag of crushed dried marijuana leaves and

seeds were recovered from his house.

Accordingly, the accused was charged with illegal sale of a foil of

marijuana dried leaves, in violation of Sec. 4, Art. II, of The Dangerous

Drugs Act,1 and illegal possession of nine (9) rolls of dried marijuana

flowering tops, eleven (11) handrolled marijuana cigarette sticks, six (6)

plastic bags containing cut stems of dried marijuana flowering tops, and

one (1) plastic bag of crushed dried marijuana leaves and seeds wrapped

in a piece of paper, in violation of Sec. 8, Art. II, of the same Act.2

Accused-appellant denied selling marijuana to Det. Almoguerra as he

knew the latter to be a policeman. He claimed that he was only buying

corn for his wife when Det. Dionida, pretending to be a corn vendor,

suddenly poked a gun at him and led him to the corner of Osmeña St.

where two tricycles with five persons on board were waiting. After being

forced to board one of the tricycles, he was brought to a warehouse near

the Makati Police Precinct where he was tortured into signing Exh. "A"

wherein he admitted possession of more prohibited drugs in his

residence.

On 9 September 1987, in a joint decision, the accused was exonerated

from the charge of unlawful possession of marijuana, but declared guilty

of illegal sale of the prohibited merchandise.3 Hence, his appeal

concerns only his conviction for illegal sale of one (1) foil of

marijuana.

Aside from proof of the actual sale, a conviction for drug-pushing requires

that the drug subject of the sale be positively and categorically identified

in open court as the very drug sold by the accused. 4

In the case at bench, only three of the six-men buy-bust team, namely,

Pfc. de la Cruz, Det. Malanyaon and Det. Almoguerra, testified for the

prosecution, and none of them was able to positively identify the foil of

marijuana supposedly sold by the accused. Pfc. de la Cruz attempted to

do so but failed since he was not even sure that what was sold was really

a foil of marijuana. In open court, he testified:

Q And you are not sure that the accused handed one

stick of marijuana?

A It was a cigarette.

Q You are not sure, why did you arrest him?

A We are (sic) not sure but we are (sic) waiting for a pre-

arranged signal by the poseur-buyer.5

Det. Malanyaon, on the other hand, when asked to make the

identification, passed the burden to Det. Almoguerra, the poseur-buyer, in

this wise:

Q And can you identify the marijuana allegedly sold by

accused to

Pat. Almoguerra during the buy-bust operation?

A During the buy-bust operation, I could no longer

identify, sir.

Q Is it not a fact that you were one of the members of the

buy-bust operation?

A Yes, sir, but it was Almoguerra who had in possession

at that time as I am (sic) telling them to have reasonable

care with the confiscated stuff (emphasis ours).6

Det. Almoguerra, the most competent person to make the proper

identification according to Pfc. Malanyaon, obviously failed likewise as he

merely relied on the letter "M" found on the foil but could not identify,

much less name, the person who actually made the mark. When asked

whether he himself marked the foil of marijuana purportedly sold to him to

distinguish it from the nine (9) other foils allegedly recovered from the

accused, and for which the latter was separately charged for illegal

possession, Det. Almoguerra categorically admitted his failure thus —

Q Now, did you make any marking on that one foil of

marijuana which was sold to you by the accused?

A I did not put any marking but I can recognize the

marking found there.

Q In other words, you did not make any marking during

that operation?

A I did not (emphasis ours).

Considering that accused-appellant was being entrapped on a buy-bust

mission, the police operatives should have carefully and meticulously

marked the evidence so that it could be presented and properly identified

in court. The drug sold by the accused constitutes the very corpus delicti

of the offense the presentation and positive identification of which are an

indispensable requirement for his conviction. The fact that the buy-bust

team led by Pfc. de la Cruz failed in this important task cannot but inure to

the detriment of the cause for the prosecution.7

The foregoing discussion would otherwise sufficiently dispose of the

instant appeal. But there are several points which appear to have been

overlooked which further render the version of the prosecution not as

credible and reliable as it was considered to be by the court a quo.

First. The alleged buy-bust operation was conducted without prior

surveillance. 8 Although not always necessary, the absence of a prior

surveillance nevertheless renders quite suspect the genuineness of

the alleged buy-bust mission where the police operatives

proceeded to the suspect's reported area of operation within hours

from being tipped off, unaccompanied by the informant, and relying

solely on the description of their quarry. In this case, the buy-bust

team led by Pfc. de la Cruz proceeded to Pateros St. with only the

description that the suspect was someone "wearing white t-shirt,

khaki pants and tennis shoes" 9 to guide them in the arrest of the

accused. Such description was so general and vague that it could

very well have applied to a number of "John Does" lurking in the

area. Besides, we find it quite incredible that accused-appellant

should single out Det. Almoguerra, the poseur-buyer, as his

prospective buyer of all the people milling in the busy street of

Pateros.

Second. Pfc. Pablo R. Singayon, the police investigator assigned to the

case, testified that Det. Malanyaon marked a P10.00-bill with the letters

"A.N. U." (acronym for Anti-Narcotics Unit) the day before the alleged

buy-bust operation on 19 March 1986 following the standard operating

procedure of preparing for a buy-bust the day before it was to be

conducted. 10 However,

Det. Malanyaon claimed to have been informed about the illegal

activities of accused-appellant in the morning of 19 March 1986

only. If this were so, then how was it that he was able to prepare the

marked money the day before as testified by Pfc. Singayon?

Third. Dets. Almoguerra and Malanyaon both claimed that they

immediately saw accused-appellant seated on a bench in front of a sari-

sari store upon arriving at Pateros Street. 11 However, Pfc. Henry de la

Cruz, likewise a member of the buy-bust team, testified that they

had to wait for forty-five minutes before their target showed up. 12

Fourth. Accused-appellant denied selling marijuana to Det. Almoguerra

as he knew the latter to be a member of the Makati Police Force. This

claim was not refuted but was even admitted by the prosecution. 13

Hence, it becomes quite easy to sustain accused-appellant for we

cannot believe that the latter would risk going to jail for life for the

measly sum of P10.00 which was what the transaction with Det.

Almoguerra would have brought him. In fact, we have already said

that in the very nature of buy-bust operations, the designated

poseur-buyer should be a perfect stranger to the suspected drug-

pusher, for normally a suspect would not transact business with

known police operatives 14 in view of the obvious risk involved. Our

pronouncement to the effect that knowledge by the accused that

the poseur-buyer is a policeman is not a sound argument enough to

support the theory that the accused could not have sold drugs to

the police cannot be applied to the instant case. In the cases where

we have so ruled, it was established that the policeman had already

bought shabu from the accused on two previous occasions 15 and

that the claim that the accused knew the poseur-buyer to be a

policeman was a mere allegation which was not proved. 16 To

repeat, that herein appellant knew Det. Almoguerra to be a

policeman was even admitted by the prosecution. 17

As is true in all criminal cases, unraveling the truth is quite difficult. More

often than not, the resolution of a case is reduced to the tedious exercise

of figuring out who of the parties is narrating the true version of the

antecedents. Thus, the reason for the various rules of evidence

formulated to guide the bench in this quest. However, foremost and

overriding such rules is the principle that innocence, not guilt, is the

presumption. Courts do not exist to declare guilty and, thus convict, every

and all persons brought and charged before them. For this reason, any

circumstance indicating possible innocence on the part of the accused is

to be carefully weighed and considered. This is what we are doing in the

instant case. In pronouncing an acquittal, we are moved by the

circumstances already mentioned which, though not enough to convince

us of accused-appellant's innocence, nonetheless effectively preclude us

from making a pronouncement that his guilt has been established beyond

all reasonable doubt which is, as it ought to be, to justify his conviction.

WHEREFORE, the judgment appealed from is REVERSED and accused-

appellant JOEL QUINTERO Y YBASCO is ACQUITTED on reasonable

doubt of illegal sale of marijuana under Sec. 4, Art. II, of "The Dangerous

Drugs Act."

SO ORDERED.

Padilla, Davide, Jr., Quiason and Kapunan.

#Footnotes

1 Crim. Case No. 22944.

2 Crim. Case No. 22945.

3 Penned by Judge Buenaventura J. Guerrero, Regional Trial

Court of Makati,

Br. 133, Original Records, pp. 242-250; Rollo, pp. 23-31.

4 People v. Martinez, G.R. Nos. 105376-77, 5 August 1994;

People v. Mendiola, G.R. No. 110778, 4 August 1994; People v.

Labarias, G.R. No. 87165,

25 January 1993, 217 SCRA 483, 488; People v. Pacleb, G.R.

No. 90602,

18 January 1993, 217 SCRA 92, 98; People v. Mariano, G.R. No.

86656,

31 October 1990, 191 SCRA 136, 148; People v. Macuto, G.R.

No. 80112,

25 August 1989, 176 SCRA 762, 767.

5 TSN, 22 September 1986, p. 9; Original Records, p. 151.

6 Id., p. 8; Id., p. 150.

7 People v. Mendiola, G.R. No. 110778, 4 August 1994 citing

People v. Macuto, 176 SCRA 762 [1989], People v. Vocente, 188

SCRA 100 [1990], People v. Mariano 191 SCRA 136 [1990];

People v. Rodrigueza, G.R. No. 95902,

4 February 1992, 205 SCRA 791, 799-800.

8 TSN, 26 November 1986, p. 14; Original Records, p. 167.

9 TSN, 10 September 1986, p. 10; Id., p. 137.

10 TSN, 26 November 1986, pp. 3-4; Id., pp. 156-157.

11 TSN, 10 September 1986, p. 4; Id., p. 131.

12 TSN, 25 August 1986, p. 6; Id., p. 123.

13 TSN, 22 September 1986, p. 10; Id., p. 152.

14 People v. Tuboro, G.R. No. 97306, 3 August 1992, 212 SCRA

33, 37.

15 People v. Salamat, G.R. No. 103295, 20 August 1993, 225

SCRA 499, 507.

16 People v. Manzano, G.R. No. 103393, 24 August 1993, 225

SCRA 590, 593.

17 TSN, 22 September 1986, p. 10; Original Records, p. 152.

The Lawphil Project - Arellano Law Foundation

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- G.R. No. 148821 July 18, 2003 The People of The Philippines, Appellee, JERRY FERRER, Appellant. Brief SummaryDocumento15 páginasG.R. No. 148821 July 18, 2003 The People of The Philippines, Appellee, JERRY FERRER, Appellant. Brief SummaryDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 213847 August 18, 2015 Juan Ponce Enrile, Petitioner, vs. Sandiganbayan (3 Division) and People of The Philippines, Respondents. FactsDocumento5 páginasG.R. No. 213847 August 18, 2015 Juan Ponce Enrile, Petitioner, vs. Sandiganbayan (3 Division) and People of The Philippines, Respondents. FactsDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- CT 200820 FTDocumento24 páginasCT 200820 FTDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- Rule 118-119 CrimPro Case DigestDocumento14 páginasRule 118-119 CrimPro Case DigestDonna Jane Simeon100% (1)

- Cruz V Yaneza Rule 114 Sec 17 Ver2.0Documento7 páginasCruz V Yaneza Rule 114 Sec 17 Ver2.0Donna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- Purganan and Tuising Cases CDDocumento4 páginasPurganan and Tuising Cases CDDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- Crim Pro - Cortes vs. Catral Vertrudes Vs BuenaflorDocumento17 páginasCrim Pro - Cortes vs. Catral Vertrudes Vs BuenaflorDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- My Chael SpeechDocumento2 páginasMy Chael SpeechDonna Jane Simeon100% (2)

- January 10Documento1 páginaJanuary 10Donna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- ApplicationDocumento1 páginaApplicationDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- March Is Fire Prevention Month SpeechDocumento2 páginasMarch Is Fire Prevention Month SpeechDonna Jane Simeon50% (4)

- Speech For The Oath Taking Ceremony of YAM CCOP 362020Documento1 páginaSpeech For The Oath Taking Ceremony of YAM CCOP 362020Donna Jane Simeon0% (1)

- Tutor Agreement v3.1 Endorsement Letter Training Log Privacy Policy ExamDocumento2 páginasTutor Agreement v3.1 Endorsement Letter Training Log Privacy Policy ExamDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- Distance Learning Program On The Rules of Conduct and Ethical Behavior in The Civil ServiceDocumento10 páginasDistance Learning Program On The Rules of Conduct and Ethical Behavior in The Civil ServiceDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- August 7 Letter For BaliteDocumento1 páginaAugust 7 Letter For BaliteDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- (Please Mention VIP's and Guests), To All Women, and Others Who Are Present Here, We Have AllDocumento1 página(Please Mention VIP's and Guests), To All Women, and Others Who Are Present Here, We Have AllDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- Malik Ibn AnasDocumento9 páginasMalik Ibn AnasDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- Illegal RecruitmentDocumento5 páginasIllegal RecruitmentDonna Jane SimeonAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- 4 People vs. Valdez - G.R. Nos. 216007-09 - Case DigestDocumento2 páginas4 People vs. Valdez - G.R. Nos. 216007-09 - Case DigestAbigail Tolabing100% (3)

- People Vs MarcosDocumento6 páginasPeople Vs MarcosPaolo CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Evid Part IIIDocumento16 páginasEvid Part IIIJenAinda não há avaliações

- Power Homes Unlimited CorporationDocumento20 páginasPower Homes Unlimited CorporationRaiya AngelaAinda não há avaliações

- Cantoria CrimProDigestDocumento6 páginasCantoria CrimProDigestqweqeqweqweAinda não há avaliações

- GR No 221981Documento7 páginasGR No 221981Ged VenturaAinda não há avaliações

- Gender and CDocumento8 páginasGender and CCrestu JinAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4Documento19 páginasChapter 4aldehspicableAinda não há avaliações

- Pio Sepulveda and Providencio P. Abragan For Appellants. Office of The Solicitor General For AppelleeDocumento12 páginasPio Sepulveda and Providencio P. Abragan For Appellants. Office of The Solicitor General For AppelleeJoannMarieBrenda delaGenteAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. 180677 February 18, 2013 VICTORIO P. DIAZ, Petitioner, People of The Philippines and Levi Strauss (Phils.), Inc., Respondents. Bersamin, J.Documento6 páginasG.R. No. 180677 February 18, 2013 VICTORIO P. DIAZ, Petitioner, People of The Philippines and Levi Strauss (Phils.), Inc., Respondents. Bersamin, J.Jasielle Leigh UlangkayaAinda não há avaliações

- People v. TorreDocumento5 páginasPeople v. TorreDarla EnriquezAinda não há avaliações

- Yadao Vs PeopleDocumento5 páginasYadao Vs PeopleAndrew Marz100% (1)

- Demurrer To Evidence With Leave of CourtDocumento8 páginasDemurrer To Evidence With Leave of CourtVincentRaymondFuellas100% (3)

- Legal Tech - Violation of Sec.5 of RA 9165Documento6 páginasLegal Tech - Violation of Sec.5 of RA 9165Neil PilosopoAinda não há avaliações

- People v. Givera 25Documento6 páginasPeople v. Givera 25Jp CoquiaAinda não há avaliações

- Summary TrialDocumento10 páginasSummary TrialSITI NURAISYAH ZULKIPLIAinda não há avaliações

- People v. GersamioDocumento1 páginaPeople v. GersamioCesyl Patricia BallesterosAinda não há avaliações

- John Durham - Jury QuestionnaireDocumento39 páginasJohn Durham - Jury QuestionnaireWashington ExaminerAinda não há avaliações

- People v. Villahermosa G.R. No. 186465Documento11 páginasPeople v. Villahermosa G.R. No. 186465XuagramellebasiAinda não há avaliações

- Criminal LawDocumento58 páginasCriminal LawDanilo Pinto dela BajanAinda não há avaliações

- People Vs TolentinoDocumento13 páginasPeople Vs TolentinoJomar TenezaAinda não há avaliações

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Justice State Regional Prosecutor San Fernando, La Union Marielle QuilacioDocumento20 páginasRepublic of The Philippines Department of Justice State Regional Prosecutor San Fernando, La Union Marielle QuilaciocaicaiiAinda não há avaliações

- People V BelgarDocumento2 páginasPeople V BelgarWilver BacugAinda não há avaliações

- People v. CastilloDocumento9 páginasPeople v. CastilloVonn GuintoAinda não há avaliações

- 6 People Vs PorioDocumento21 páginas6 People Vs PorioKirsten Denise B. Habawel-VegaAinda não há avaliações

- PIGOTT-Texas Court of Criminal Appeals BriefDocumento36 páginasPIGOTT-Texas Court of Criminal Appeals BriefShirley Pigott MDAinda não há avaliações

- Gelloano, Mary Rose R. - Midterm-Exam-BACC3Documento3 páginasGelloano, Mary Rose R. - Midterm-Exam-BACC3Mary Rose GelloanoAinda não há avaliações

- Offence of Unlawful Assembly Under PPCDocumento2 páginasOffence of Unlawful Assembly Under PPCZeesahnAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence NotesDocumento72 páginasEvidence NotesDebasmita BhattacharjeeAinda não há avaliações

- Marquez Vs PeopleDocumento2 páginasMarquez Vs PeopleNiña Grace AguimodAinda não há avaliações