Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

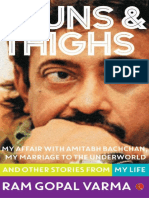

Presenting The Buddha Images Conventions PDF

Enviado por

Anonymous udbkKpS38Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Presenting The Buddha Images Conventions PDF

Enviado por

Anonymous udbkKpS38Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Presenting the Buddha: images,

conventions, and significance in early

Indian Buddhism

Juhyung Rhi

After the creation of the Buddha image around the begin- around the fifth to sixth century CE displaying the preaching

ning of the Common Era, the most critical juncture in the gesture (dharmacakra-mudrā) and the earth-touching gesture

history of Buddhist icons, at least within India, is probably (bhūmisparśa-mudrā) (Figures 1 and 2).1 These two image types

the emergence of Buddha images in the middle Gangetic valley present the Buddha2 clearly engaged in two important events

from his life: the First Sermon and the Enlightenment. This

is in stark contrast to earlier forms of the Buddha in iconic

images, which feature little in the way of narrative. From this

point on, these two types, especially the bhūmisparśa, were the

most common iconic images3 of the Buddha throughout later

Buddhist art from India; they also simultaneously impacted

other parts of the Buddhist world, such as Burma and later

Thailand.4 This phenomenon is presumably related, at least

in part, to the rise of Sārnāth and Bodhgayā, the holy places

of the two great events, as important artistic and religious

centres of Indian Buddhism. But their rise was possibly linked

to the emerging of doctrinal meanings that contemporary

Buddhists attached to these two events. It has been suggested

that the bhūmisparśa type was perhaps equated with the idea

of pratītya-samutpāda, or dependent origination, which the

Buddha supposedly attained at the time of enlightenment

and which was expressed in an immensely popular verse,

commonly carved as a votive formula on stone images or clay

tablets (which were installed inside small stupas).5 Although I

wonder whether this link to pratītya-samutpāda convincingly

explains the phenomenon, I nonetheless believe that the rise

of these two types reflects a contemporary concern among

Indian Buddhists about which moment in the Buddha’s life is

the most crucial in qualifying him as such.6

In this paper, I return to the period before this important

change took place in Indian Buddhism – that is, the centuries

after the creation of the Buddha image (around the beginning

of the Common Era) – exploring the ways in which the Buddha

was presented in iconic images and what significance we may

be able to infer from their iconographic configurations.7 I

touch on all three major centres of Buddhist art in this period

– Gandhāra, Mathurā, and Āndhra, the last one comprising

Amarāvatī and Nāgārjunakoṇḍa – but focus inevitably on

Figure 1 Buddha from Sārnāth, late fifth century, H. 160 cm. Sārnāth Museum. Gandhāra, where a greater variety was shown in a significantly

Photograph: J. Rhi et al. larger body of productions. Such an exploration is certainly

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 1 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

and the bodhi tree is open to numerous possibilities.9 Several

standing images of the kapardin type carry an inscription

noting that the image had been placed at a spot where the

Buddha used to practise caṅkrama, or walking meditation,10

giving the impression that the image is linked to the Buddha’s

practice. Again, though, the meaning of such a remark in

the inscription on the image itself is not easy to determine,

as it could simply indicate the location of the image. Among

Gandhāran Buddhas, there are straightforward depictions

of the Buddha engaged in specific narrative moments, such

as images of the fasting Buddha,11 an image of the Buddha

holding a bowl, which clearly represents the offering of dust by

a previous incarnation of Aśoka to the Buddha,12 images of the

Buddha performing the twin miracle (emitting fire and water),

which most likely portrays an occurrence in the Miracle at

Śrāvastī,13 and images of the Buddha showing a snake bowl

to Uruvilvā-Kāśyapa.14 However, these are extremely limited

exceptions and, beyond these, most other images lack clear

signs that would connect them to narrative moments from the

life of the Buddha. Buddha images from Āndhra are even more

monotonous and are almost wholly devoid of any narrative

indications.15

Iconographic configurations of Buddha images during

this early period were largely conventions not necessarily

linked to particular narrative themes from the Buddha’s

life. This is most symptomatic in the prevalent use of the

so-called abhaya-mudrā16 for images from this period. This

Figure 2 Buddha from Sārnāth, sixth century, H. 52 cm. Sārnāth Museum mudrā, characterised by a raised right hand with the palm

Photograph: American Institute of Indian Studies (AIIS).

facing outward, was widely employed for Buddha images in

all three of these regions. Especially in standing Buddhas, its

too broad and too complex to be fully addressed in a short use was universal and consistent despite minor differences

paper, but I hope to take this opportunity to discuss some of in positioning (Figures 3–5). Similar hand gestures are also

my preliminary observations. used in divine or royal figures outside of India, including

As mentioned earlier, in independent images of the Buddha Iran and sometimes the Mediterranean, conveying a range

created in any of these three regions during the first few of implications such as benediction, protection or salvation;

centuries of the Common Era, we find little of the narrative the Indian abhaya-mudrā was perhaps adopted from Parthian

intent that would clearly connect the images to particular Iran and thereby evoked parallel meanings.17 It is clear that

incidents in the Buddha’s life. This is striking in light of our the mudrā was used generically for standing Buddhas with

general assumption that early Buddhist art, as seen in aniconic neither particular narrative associations nor a restrictive tie

representations at early monuments, such as stupas at Bhārhut to a specific Buddha.18 A handful of standing Buddhas with

and Sāñchī, was heavily concerned with the life – and the abhaya-mudrā from Gandhāra have narrative scenes, such as

previous lives – of the Buddha (Śākyamuni). However, nar- the Buddha’s mahāparinirvāṇa, carved on pedestals,19 but it

rative depictions on these early monuments were designed is clear that such scenes have nothing to do with the figural

primarily to embellish the monuments and, strictly speaking, forms of the Buddha standing on the pedestal.

their significance either in relation to the central monument Abhaya-mudrā was also commonly used for seated Buddha

itself or within the overall context of the monastery is not clear. images in Gandhāra and Mathurā (Figures 6 and 7).20 In

This was also true of Buddhist art in Gandhāra. Although we Gandhāra, the Buddha displaying abhaya-mudrā frequently

have numerous narrative reliefs that once decorated Buddhist appears in narrative reliefs depicting any theme of the Buddha’s

stupas, there is significant discontinuity between these nar- life that requires a seated Buddha (Figure 8). This is less con-

rative reliefs and the iconic images. This is clearly revealed spicuous in Mathurā, where there are fewer extant narrative

by the complete absence of any images that directly relate to depictions and represented themes. But it is clear that abhaya-

the Defeat of Māra (usually equated with the Enlightenment) mudrā was most commonly used and was not restricted to the

and the First Sermon, which are extensively represented in representations of specific themes. A prominent exception is the

narrative reliefs. Defeat of Māra, in which the Buddha in the pose of touching the

In Mathurā, images of the so-called kapardin type are earth was invariably used in both regions (Figure 9).21 In Āndhra,

usually seated against a bodhi tree,8 and this perhaps suggests it is difficult to locate seated abhaya-mudrā Buddhas among

that the scenes are in some way connected to the Buddha’s the extant independent images, since most of the remaining

enlightenment. But their specific narrative implications are ones appear in a standing pose. However, seated Buddhas

difficult to identify, as the relationship between the image carved as part of the relief decorations of stupas invariably

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 2 04/10/2013 15:43

P R e s e n t i n g t h e B u d d h a : i m a g e s , c o n v e n t i o n s , a n d s i g n i f i c a n c e i n e a R ly i n d i a n B u d d h i s m

Figure 3 Buddha from Sahrī-Bahlol, Gandhāra, second century, H. 264 cm. Peshawar Museum. Photograph: J. Rhi.

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 3 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

Figure 4 Buddha from Govindnagar, Mathurā, mid-third century, H. 101 cm. Figure 5 Buddha from Amarāvatī, third century, H. 197 cm. Amrāvatī Museum.

Mathurā Museum. Photograph: J. Rhi. Photograph: J. Rhi et al.

show abhaya-mudrā; the seated abhaya-mudrā Buddha, as if it gesture) (Figures 11 and 12). Chronologically, the two seem

were a handy device which served all purposes, is commonly to have appeared later than seated abhaya-mudrā Buddhas.24

used in narrative scenes (Figure 10).22 Evidently, independent In Mathurā, the earliest securely datable specimen of the

images of the seated abhaya-mudrā Buddha were not associated dhyāna-mudrā Buddha shows up during the later first half

exclusively with any narrative themes, regardless of region. It of the second century of the Kaniṣka era (starting in 127/8

could be conjectured, for instance, that in Gandhāra a scene CE), the third quarter of the third century CE (Figure 13).25

carved on the frontal face of a pedestal provides a seated Buddha Its appearance in Gandhāran Buddhas must be earlier,

with a specific narrative association, whereas in images from presumably during the second century CE. The precedence

Mathurā such scenes are totally absent. But this would then between dhyāna-mudrā and dharamcakra-mudrā in seated

mean having to face the troubling reality that pedestals of seated Gandhāran Buddhas is difficult to discern, but it is clear that

abhaya-mudrā Buddhas from Gandhāra represent few notable the two flourished side by side throughout a very late period in

scenes, let alone any narrative depictions.23 Gandhāran art, though we seem to see more late specimens in

Two other major types of seated Buddhas existed in dharmacakra-mudrā Buddhas.26 From Mathurā, we have only

Gandhāra and Mathurā: those showing dhyāna-mudrā (the two examples of the dharmacakra-mudrā Buddha, which date

meditating gesture) and dharmacakra-mudrā (the preaching as late as the fourth to the fifth century.27

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 4 04/10/2013 15:43

P R e s e n t i n g t h e B u d d h a : i m a g e s , c o n v e n t i o n s , a n d s i g n i f i c a n c e i n e a R ly i n d i a n B u d d h i s m

The depiction of the Buddha displaying dhyāna-mudrā has

a longer history in relief carvings that appear to represent a

narrative theme. It was used distinctively in a series of narra-

tive reliefs from Swāt (north of the Peshawar valley) in which a

meditating Buddha is flanked by Brahmā and Indra (Figure 14),

which are usually dated to the beginning of the Common Era

and thus considered to be the oldest Buddhist stone carvings

with anthropomorphic depictions of the Buddha created in

the northwest of the subcontinent.28 The scene is commonly

regarded as the Entreaty for the Buddha to preach by Brahmā

and Indra.29 Yet it was only in the second century that the pose

was adopted for independent images of seated Buddhas in the

Peshawar valley, which we may call Gandhāra proper.

A notable feature of dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas is that many are

seated on grass spread across the top of the pedestal (Figure 11).

The pedestal itself is invariably decorated on each side with a

pair of Indo-Corinthian pillars. This design seems to have

changed with the adoption of the pedestal imitating a wooden

dais topped with a cushion (Figure 15). The stylistic features of

dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas suggest that those seated on a cushion

generally date later than those on grass. This suggests, perhaps,

that meditation in images of the dhyāna-mudrā Buddha was at

first thought of as taking place in a less domesticated setting

or even in the wilderness. We might wonder whether the grass

motif on the image pedestal functioned as a marker for a

particular narrative theme. It might be suspected that, unlike

seated abhaya-mudrā Buddhas, narrative consideration of some

sort was reflected in the creation of this type for independent

images. In narrative reliefs, dhyāna-mudrā was used exclusively Figure 6 Buddha from Gandhāra, second–third century, H. 46 cm. National

Museum, New Delhi. Photograph: J. Rhi et al.

for the Buddha in the scenes of the Entreaty to Preach and the

Indraśailaguhā (more commonly known as the Indra’s visit)

(Figure 16).30 Depictions of the Entreaty to Preach in Gandhāra

proper, rather than those from early Swāt, were equally divided

in terms of hand gestures of the Buddha between abhaya-mudrā

and dhyāna-mudrā, although the former seems to have outnum-

bered the latter.31 On the other hand, in the Indraśailaguhā,

the Buddha invariably shows dhyāna-mudrā. Were some

independent images of the dhyāna-mudrā Buddha meant as

another type of icon that portrays the Buddha meditating in the

Indraśailaguhā? The theme was fairly important in Gandhāra

and Mathurā, and there are several examples from Gandhāra in

which the scene was expanded in compositions in stele format, a

rare moment of privilege for narrative themes.32 I have elsewhere

noted the prominence of the theme in Gandhāra and Mathurā

during the first several centuries of the Common Era.33 Drawing

attention to a textual passage in which the Indraśailaguhā was

presented as part of the Entreaty to Preach, I suggested that the

theme was given such prominence in the two regions because

it represents the anticipation of the Buddha’s first sermon.

This reflected in turn the notion that for an enlightened one to

preach dharma without simply passing into mahāparinirvāṇa

right after enlightenment was a more important prerequisite

for becoming a Buddha than enlightenment itself. Nonetheless I

am hesitant to link independent dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas to this Figure 7 Buddha from Govindnagar, Mathurā, mid-third century, H. 115 cm.

particular narrative theme because no other specific details – Mathurā Museum. Photograph: J. Rhi.

such as a cave setting, Indra or the lyre-player Pañcaśikha – are

present; the presentation of the Buddha in this configuration Buddhas took place outdoors seems to have gradually been

is simply too abstract. In any case, the notion that the Buddha’s forgotten with the adoption of a pedestal styled in the form of

meditation presented in such independent dhyāna-mudrā a wooden dais furnished with a cushion.

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 5 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

Figure 8 Entreaty to Preach on a stupa from Sikri, Gandhāra, first–second century, H. 33 cm (relief). Lahore Museum. Photograph: J. Rhi.

Figure 9 Defeat of Māra, from Gandhāra, first–second century, H. 39 cm. Peshawar Museum. Photograph: J. Rhi.

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 6 04/10/2013 15:43

P R e s e n t i n g t h e B u d d h a : i m a g e s , c o n v e n t i o n s , a n d s i g n i f i c a n c e i n e a R ly i n d i a n B u d d h i s m

Figure 10 Buddha and worshippers from Amarāvatī stupa, third century.

Chennai Museum. Photograph: J. Rhi et al.

Figure 12 Buddha from Gandhāra, second century, H. 75 cm. Peshawar Museum.

After Rhi 1999: pl. 55.

In an intriguing contrast to dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas,

Buddhas holding hands in dharmacakra-mudrā never sit

on grass spread on a pedestal decorated with a pair of Indo-

Corinthian pillars (Figure 12). The dharmacakra-mudrā

Buddha invariably sits either on a cushion placed on a

wooden dais-style pedestal decorated with a pair of lions or

legs composed of stylised lion paws sometimes with lion heads

on each side, or on a full lotus blossom (see Figure 17). When

sitting on a cushioned wooden dais, the Buddha’s preaching

evidently takes place in a more domesticated setting. In what

appears to be an interesting coincidence, the dharmacakra-

mudrā Buddha is shown with the right shoulder bare in most

instances. This is somewhat peculiar: in the textual tradition,

revealing a shoulder (ekāṃsam uttarāsaṅgaṃ kṛtvā, etc.),

invariably the right shoulder, is prescribed for saluting either

the Buddha or a teacher, and is thus performed by monastics

or lay disciples of the Buddha, not by the Buddha himself.34

Although we have few clues to this puzzle, this manner of

dressing is probably tied to the domesticated setting suggested

by the cushioned pedestal.

Interestingly, dharmacakra-mudrā is relatively rare in

narrative depictions of the Buddha’s life. It appears only in a

small number of depictions of the First Sermon, despite our

common designation of it as ‘the (turning) the dharma wheel’.

Figure 11 Buddha from Gandhāra, second–third century, H. 61 cm. Chandigarh It also appears in other themes, such as the presentation of

Museum. Photograph: J. Rhi. the first Buddha image created by King Udayana, in which the

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 7 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

gesture, also known by the same name by art historians, was

eventually established for the depiction of the Buddha engag-

ing in the First Sermon in Sārnāth and Ajaṇṭā beginning in

the late fifth century (see Figure 1).39 The designation of the

Gandhāran dharmacakra-mudrā may not be too far off the

mark, but I suspect that the mudrā probably conveyed broader

or more profound implications than a mere symbol to signify

preaching.

In the mid-to-late phase of Gandhāran art, the dhyāna-

mudrā Buddha and the dharmacakra-mudrā Buddha emerged

as two dominant types of seated Buddhas. These were not

simply, however, two concurrent types; instead, the two might

have been related, or even used in contradistinction. The

contrast between the two types is tantalising, and Gandhāran

Buddhists possibly perceived their diverging significances,

or even sometimes constructed it, through their mutual

relationship, by the time the dharmacakra-mudrā Buddha

was established as another popular type. In dhyāna-mudrā,

the Buddha is apparently deeply absorbed in meditation and is

cut off from the outside world. In such depictions, the Buddha

is static, withdrawn in the bliss of impenetrable enlightenment

or solitary mental concentration (samādhi). Most images of

the dhyāna-mudrā Buddha are shown in an abstract form, but

the Buddha sometimes appears in the extraordinary narrative

setting of the Indraśailaguhā framed in a magnificent stele

(Figure 16). On the other hand, in dharmacakra-mudrā, the

Buddha is active – whether the action is preaching, reception

or approval, if it can be glimpsed in examples, though limited

in numbers, of its use in narrative depictions. He is no longer

in a state of self-absorption, but conspicuously engages with

the imaginary audience or viewers. In its advanced form, in

Figure 13 Buddha from Mathurā, dated year (1)36 (ca. 163 CE), H. 24.4 cm.

complex steles, for instance, such as one from Mohammed-

National Museum, New Delhi. After GSRB 1988: pl. 7. Nari, the dharmacakra-mudrā is coupled with a grandiose

lotus seat with which the Buddha overlaps (Figure 17). In

this act of the Buddha, its original significance – whatever it

Buddha is apparently in the act of approving the first Buddha was – was further exalted, or perhaps even another layer of

image rather than preaching.35 All of these are in a distinctly meaning was added. The rolling water from which the lotus

late style, much more so than a number of independent emerges suggests fluidity, as if violently moving toward crea-

images of this type. I suspect that dharmacakra-mudrā was tion. It reminds one of an ocean, highlighted in a number of

first devised for independent images and later adopted, in rare Buddhist scriptures, rather than a tranquil pond of Sukhāvatī,

instances, in narrative relief depictions. The dharmacakra- as the Amitābha theorist would have us believe. The Buddha

mudrā Buddha is also frequently seated on a lotus blossom seems to emerge from the rolling water along with or like the

in triads accompanied by two bodhisattvas, or at the centre lotus. Or, viewed in contrast with dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas –

of complex steles (Figure 17). The same combination of the particularly one that appears in a magnificent depiction of

mudrā and the lotus throne also appears in independent the Indraśailaguhā (Figure 16) – this Buddha looks as if he has

Buddha images, which date somewhat later than the earliest been roused out of meditative quiescence (even if the Buddha

examples in triads. The Buddha in such triads and steles was in the Mohammed-Nari stele appeared decades, if not at least

once commonly thought to be Śākyamuni Buddha perform- a century, later).

ing the Great Miracle at Śrāvastī in an incident from his life, In the Indian Buddhist tradition, the lotus is a symbol of

but some have also alternatively identified it as Amitābha purity and sacredness, while the lotus seat is often thought

Buddha preaching in his paradise, Sukhāvatī.36 Although the to be a symbol of the Buddha’s supernatural power.40 It

Great Miracle theory is dubious, the Amitābha theory, which was also used in Buddha images commonly dedicated by

has been rigorously promoted in recent years, is backed by Mahāyānists.41 In Indian mythology, the lotus is a symbol

neither substantial evidence nor a convincing argument.37 In of creation, a meaning eloquently illustrated in the crea-

any case, I wonder whether our conventional understanding of tion of the world by Brahmā seated on a lotus.42 A similar

this mudrā as the ‘preaching’ gesture fully reflects its original metaphorical usage is found in the Buddhist tradition as well.

significance as conceived by Gandhāran Buddhists.38 The The Tathāgatotpattisambhavanirdeśa (the Rising Emergence

Gandhāran dharamcakra-mudrā was sometimes used for the of the Tathāgata) preserved in a Chinese translation by

First Sermon in the late phase of Gandhāran art, and another Dharmarakṣa in 291 – which dates closely to the Gandhāran

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 8 04/10/2013 15:43

P R e s e n t i n g t h e B u d d h a : i m a g e s , c o n v e n t i o n s , a n d s i g n i f i c a n c e i n e a R ly i n d i a n B u d d h i s m

Figure 14 Entreaty to Preach probably from Swāt, first century, H. 30 cm. Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Berlin. Photograph: J. Rhi.

dharmacakra-mudrā Buddhas seated on a lotus – recounts the

following passage in an elucidation of one of the 10 causes and

conditions for the emergence of the Buddha:

When the destruction by water [apsaṃvarta] takes

place, it ubiquitously pervades the space in the three

thousand/great thousand worlds. A number of lotuses

called the ‘Virtue-Fulfilled Treasure’ are naturally born.

All of them cover the places where the destruction by

water took place. If lotuses are naturally born, Mahādeva

and Śuddhavāsadeva immediately know that as many

Buddhas must emerge in the eon. [Then, winds by

various names blow and create diverse realms, heavenly

palaces, mountains, oceans, treasures, trees, etc.]

Bodhisattvas think, ‘Now the Tathāgata emerges to edify

all bodhisattvas. For this reason, he appears himself in

the world.’ [Then, by emitting light the Buddha teaches

living beings in various ways. This is recapitulated in a

verse.]

As the lotus is born, the Buddha emerges.

All the rejoicing devas saw Buddhas of the past.

...

The best of men (narottama) likewise attains the

kingship of dharma,

And becomes the adoration and recourse of all living

beings.43

Figure 15 Buddha from Loriyān-Tangai, Gandhāra, third–fourth century, H.

65 cm. Indian Museum, Kolkata. Photograph: J. Rhi et al.

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 9 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

Figure 16 Buddha meditating in Indra’s cave (Indraśailaguhā) from Mamane-Ḑherī, Gandhāra, dated year 89 (ca. 216 CE), H. 96 cm. Peshawar Museum. After

PGC: pl. 1.

This scene apparently takes place at a cosmogonic moment could be presumed on the basis of its conventional definition

after everything has been destroyed and submerged by water. as ‘preaching’.

Two later translations of this text, dated to 420 and 712, specify In considering this problem, we cannot fail to notice the

the time as ‘when the world is about to be created’. They also apparent similarity between the Gandhāran dharmacakra-

name the lotus(es) the ‘Emergence of the Tathāgata (Adorned mudrā and the distinctive mudrā of Vairocana or

with Various Virtuous Treasures)’.44 As the identification of the Mahāvairocana, the Buddha of ultimate reality formulated in

emergence of the Buddha with the birth of the lotus becomes the Avataṃsaka or the esoteric Vajradhātu tradition, which

clearer, so too does the contextual significance of the Buddha becomes standardised in later esoteric iconography (the

in the cosmogonic tale.45 Although this passage is only a textual mudrā is often identified with the Sanskrit term bodhyagrī-,

parallel, rather than a source, it nonetheless evokes a spirit that bodhyaṅgī-, or bodhaśrī-mudrā but is better known by the

underlies the imagery of the dharmacakra-mudrā Buddha on Japanese chikenin, the Wisdom Fist mudrā; bodhyagrī-mudrā

the lotus. We cannot of course simply equate the dharmacakra- is used here despite some confusing problems46) (Figure 18). In

mudrā Buddha with the one on the lotus. But this passage does the Gandhāran dharmacakra-mudrā, the right fingers, often

suggest that the so-called dharmacakra-mudrā was used to rep- the little and ring fingers, loosely embrace or cover the upper

resent the active aspect of seated Gandhāran Buddhas with portion of the left fingers (the thumb and the index finger

broader, and potentially more profound, implications than usually touch each other, though not as distinctly as the fingers

10

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 10 04/10/2013 15:43

P R e s e n t i n g t h e B u d d h a : i m a g e s , c o n v e n t i o n s , a n d s i g n i f i c a n c e i n e a R ly i n d i a n B u d d h i s m

Figure 17 Buddha on a lotus from Mohammed-Nari, Gandhāra, third–fourth century, H. 105 cm. Lahore Museum. Photograph:

J. Rhi.

in the so-called vitarka-mudrā or vyākhyāna-mudrā, and not This means neither that the Gandhāran dharmacakra-mudrā

consistently in all examples); in the bodhyagrī-mudrā, the left has an exclusive tie to Vairocana (or Mahāvairocana) nor

index finger is raised straight and held by the right fist. Despite that any of the Gandhāran dharmacakra-mudrā Buddhas

this difference, the configuration of fingers shows a resem- portray such Buddhas from the advanced esoteric Buddhist

blance between the two, as some scholars have observed.47 The system, which would be obviously too early for the period of

Gandhāran dharmacakra-mudrā is extremely rare in other Gandhāran Buddhas. Yet this does suggest that the Gandhāran

parts of India: I can cite only two examples: a depiction of the dhamacakra-mudrā possessed greater semantic potential,

First Sermon from Mathurā (fourth century)48 and a seated which eventually helped to bring forth a distinctive gesture

image of what appears to be Mahāvairocana from Udayagiri in for the esoteric cosmic Buddha.

Orissa (tenth century).49 On the other hand, bodhyagrī-mudrā, We should also note the scenes carved on the frontal face

probably devised in eastern India by the seventh century, is of the pedestal in dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas and dharmacakra-

known mostly in Java, East Asia (particularly Korea and Japan) mudrā Buddhas from Gandhāra. In seated abhaya-mudrā

and Tibet.50 It is possible that bodhyagrī-mudrā was created in Buddhas, the most common motif is two–five-petalled rosettes

reference to, if it is not a derivation of, the earlier Gandhāran or lotuses (rather than a lotus throne).51 I suspect that they were

dharmacakra-mudrā, or that the two developed out of the same not simply auspicious or decorative motifs but also potentially

prototype that existed in the non-Buddhist Indian tradition. carried symbolic meaning related to the enlightenment of

11

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 11 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

pedestal started relatively late in Gandhāran Buddhist imagery

when abhaya-mudrā Buddhas were no longer popular. The

choice of the theme for pedestals, then, may merely reflect its

growing importance during this late phase. Prince Siddhārtha’s

first meditation is given considerable importance in textual

accounts of the Buddha’s life. When the Buddha gives up

austerities to look for an alternative path to enlightenment, he

recalls his first meditation under the Jambu tree and decides to

switch methods.57 The so-called Four Encounters – that is, the

prince’s encounters with four major aspects of life outside the

four gates of Kapilavastu: old age, illness, death and mendicant

practice – may have exposed the vanity of earthly life; but it

was the First Meditation under the Jambu tree when he first

engaged seriously in a meditative practice through which to

reflect on life.58 Yet we have relatively few depictions of the

theme in narrative reliefs. A fair number of independent

images depict the bodhisattva in meditation, but the number

is not as large as that of the bodhisattva holding a water vase,

which is conventionally identified as Maitreya.59 However, the

prominence of the theme on pedestals with Buddha images,

and its predominance in the case of dharmacakra-mudrā

Buddhas, is quite remarkable, whereas the bodhisattva

holding a water vase has a much more limited presence as far

as seated Buddha images are concerned. The theme of the First

Meditation was presumably added to the pedestals of Buddha

images to mark the very first moment of the Buddha’s awaken-

ing as a religious practitioner, even before the Great Departure.

Figure 18 Mahāvairocana Buddha by Unkei, Japan, 1176, wood, H. 99 cm. Enjōji, Gregory Schopen has drawn our attention to multiple pas-

Nara. After GNB 1970: pl. 50.

sages from the Mūlasarvāstivāda-vinaya concerning the image

under the shade of the Jambu tree. One such passage reads:

the Buddha, although this awaits further corroboration.52

Rosettes or lotuses are virtually non-existent among Buddhas When the Householder Anathapiṇḍada went to the

of the dhyāna and dharmacakra types. Ordinary narrative Blessed One, he, arriving there, paid deference to the

scenes from the Buddha’s life are also utterly absent from feet of the Blessed One with his head and sat down at

these groups. Instead, in dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas, the most the one end of the assembly. So seated the householder

prominent is a series of meditating Buddhas (Figure 19);53 Anathapiṇḍada said these words to the Blessed One: ‘… if

in dharmacakra-mudrā Buddhas, we see most frequently the Blessed One were to order it, I will make an image of

a bodhisattva in meditation (Figure 20).54 The motif of a the Sitting in the Shade of the Jambu Tree.’ The Blessed

bodhisattva in meditation is also found in the pedestals of One said: ‘By my order you must have one made!’60

a number of dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas, though not as often as

a series of meditating Buddhas. It is difficult to make sense A number of other passages in this vinaya and the related

of the significance of a series of meditating Buddhas on the texts speak of ‘an image of the Sitting in the Shade of the Jambu

pedestal of a dhyāna-mudrā Buddha. A possible explanation is Tree’.61 These passages were apparently developed out of the

that they highlight the universality of the Buddha’s meditation: following, well-known passage from the Sarvāstivāda-vinaya,

the Buddha of the present meditates in the main image above, which I once cited as evidence for the period when only

just as Buddhas from the past or those residing in various other images of the bodhisattva (in the pre-enlightenment stage of

buddhafields in the pedestal meditate. The Buddha does not Śākyamuni) – like those of the kapardin type from Mathurā –

meditate alone; all other Buddhas from other times and other were present in Buddhist art prior to the emergence of images

worlds join him. of the Buddha. The passage reads:

Both in Gandhāra and Mathurā, the bodhisattva in medi-

tation is usually identified as Prince Siddhārtha practising The householder Anathapiṇḍada said, ‘The Blessed

the first meditation under the shadow of a Jambu tree.55 If One, since it is not permitted to make an image of the

we accept this identification, we are then faced with a new Buddha’s body, I pray that the Buddha will grant that

question: how does this scene function on the pedestal of a I make an image of the time [when the Buddha was] a

Buddha? Although it is just as common among the scenes bodhisattva. Is that acceptable?’ The Buddha answered,

carved on the pedestals of dharmacakra-mudrā Buddhas, it ‘You may make an image of the bodhisattva.’62

also appears in those of dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas and those of

standing Buddhas.56 It is not found in abhaya-mudrā Buddhas, It seems apparent that the ‘bodhisattva image’ in the

but this is probably due to the fact that carving the theme on a Sarvāstivāda-vinaya was changed to or equated with the ‘image

12

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 12 04/10/2013 15:43

P R e s e n t i n g t h e B u d d h a : i m a g e s , c o n v e n t i o n s , a n d s i g n i f i c a n c e i n e a R ly i n d i a n B u d d h i s m

Figure 19 Detail of a seated Buddha (Figure 11): a series of meditating Buddhas on the pedestal. Photograph: J. Rhi.

sitting in the Shade of the Jambu Tree’ in the Mūlasarvāstivāda- indication of, or even an allusion to, the Enlightenment or the

vinaya. I suspect that the change or reinterpretation coincides First Sermon in independent images can perhaps be attributed

with the prominence of the First Meditation on the pedestals to the general lack of narrative concern in the conception of

of Buddha images. Either the popularity of the convention in Buddha images, though such a concern was prominent in

images influenced the creation or modification of the textual narrative reliefs. Or perhaps for Buddhists in Gandhāra, if

passages or vice versa. not for those in Mathurā, where fewer specimens exist, the

We have examined thus far diverse aspects of Buddha Enlightenment and the First Sermon did not enjoy prestigious

images prior to the emergence of icons of the Buddha that positions as they did for later Buddhists in the middle Gangetic

highlight major events of the Buddha’s life. What appears to be valley. Whatever the case, we need to admit that the concep-

an anomaly in this phase is the total absence of Buddha images tion of the Buddha’s sacred history and his sacred icons differ

displaying bhūmisparśa-mudrā in the localities (Gandhāra and markedly from the newer, more prominent changes that took

Mathurā) where the Defeat of Māra was invariably depicted place in the centuries that followed and with which we are

with the distinctive hand gesture.63 One possibility is that more familiar today.

the Defeat of Māra was not equated with the Enlightenment We know little about the circumstances surrounding the

and thus the bhūmisparśa-mudrā Buddha was not considered invention of another dharmacakra-mudrā at Sārnāth. But the

important enough to be deployed in independent images. Gandhāran dharmacakra-mudrā had been adopted in narrative

However, in Gandhāra there is at least one example in which representation of the First Sermon in Mathurā by the fourth

the Defeat of Māra was apparently used for representing the century.66 It was about a century later that another gesture,

Enlightenment as one of the four major events in the Buddha’s which we also call dharmacakra-mudrā, began to be used in

life.64 The Gandhāran mode of representing the Enlightenment Buddha images in Sārnāth and Ajaṇṭā (see Figure 1). Combined

with the Defeat of Māra was also adopted in a Mathurā relief with the motif of the dharma wheel and the antelopes, it

panel of the four major events along with the Descent from clearly declares its connection to the First Sermon – though

the Trāyastriṃśa heaven.65 Among independent Gandhāran what the ‘First Sermon’ means precisely in this case is poten-

Buddha images, the First Sermon is also not identifiable, as tially problematic. The efflorescence of this type has given rise

we do not find any dharma wheel or antelopes on pedestals to our practice of calling a similar Gandhāran gesture by the

of seated Buddhas; with the Buddha alone, detecting the same name. The bhūmisparśa-mudrā had also been adopted

theme would be difficult, given the lack of a distinctive sign from Gandhāra in narrative representations in Mathurā by

like bhūmisparśa-mudrā for enlightenment. In fact, I doubt the third century and developed into a separate icon possibly

whether any dharmacakra-mudrā Buddhas were meant in Sārnāth by the end of the sixth century (see Figure 2).67

to represent the First Sermon. The absence of an explicit The bhūmisparśa type was used as the central icon at the very

13

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 13 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

Figure 20 Detail of a seated Buddha (Figure 12): a bodhisattva in meditation. Photograph: J. Rhi.

more than one Buddha is known in textual and epigraphical

spot of the Enlightenment, Bodhgayā, and the icon produced sources relevant to the period. Nonetheless, Śākyamuni was no

numerous replications in vast areas of the Buddhist world in doubt predominant in the visual imagery of Buddhas and, as I

the East. The emergence of these two types parallels a growing have argued elsewhere (Rhi 2010), other Buddhas were often

predilection for iconographic specificity, which was increas- presented with virtually no iconographical distinction from

ingly prominent with the rise of esoteric Buddhism during Śākyamuni, especially during the early period of Buddhist art.

this period. The prominence of the two types perhaps reflects a 3. In this paper, I use the word ‘image’ in the sense of independent

images verging on three-dimensional statues. I do not use the

belief in the inherent mystic power involved in these two great

word ‘statue’ because, strictly speaking, many images are carved

acts of the Buddha. Buddhist art was thus entering a new era. as reliefs rather than as truly three-dimensional statues, and some

images, such as those of the seated kapardin type from Mathurā,

have subsidiary attendant figures carved on the same relief.

4. Luce 1969: 130–35; Boisselier 1975.

5. Leoshko 2000/2001: 70–75; for the verse, Boucher 1991.

6. A parallel concern about a historical moment of the Buddha’s life,

Notes probably also generated on doctrinal grounds, may be seen in

the predominance of another type from outside India, the image

1. By the ‘dharmacakra-mudrā’ in the above sentence, I mean the

of the Buddha’s mahāparinirvāṇa in Central Asia; Miyaji 1992:

mudrā that first appeared in Buddha images from the middle

482–524.

Gangetic valley around Sārnāth and may be more properly called

7. This paper is written in close connection with my two other

as such, rather than a similar gesture used earlier for Buddha

works, Rhi 2010 and forthcoming. The former argues that

images from Gandhāra, though I also use it for the latter in my

Buddha images in Gandhāra were made with little concern for

discussions below. The date of the emergence of this dharmacakra-

the iconographic specification of different Buddhas, and the

mudrā and bhūmisparśa-mudrā in independent Buddha images

current paper is part of a preliminary answer as to how, then,

is difficult to pinpoint; but at least according to extant material

they should be read. The latter concerns the peculiar prominence

evidence, the former was established by the late fifth century in

of a narrative theme in Gandhāran art, Indraśailaguhā, and the

Sārnāth, and the latter seems to have been employed for images,

current paper is conscious of the role that the theme may have

again at Sārnāth, during the sixth century. For the emergence of

played in Gandhāran Buddhist imagery. I would also like to note

bhūmisparśa-mudrā Buddhas in the middle Gangetic valley, see

that my analysis of Buddha images is restricted to stone images

Leoshko 2000/2001.

because I believe that stone images were the dominant form of

2. I use the word ‘Buddha’ here with the definite article in the

image-making and dedication in Gandhāran monasteries.

conventional way, which designates the founder of Buddhism or

8. Sharma 1995: figs 60, 65, 74, 88.

the historical Buddha, Śākyamuni, as in the common phrase ‘the

9. Noting the fact that most images of the kapardin type are called

life of the Buddha’, or represents Buddhas in the collective sense,

‘bodhisattva’ in the inscriptions, I have suggested that the type –

although I admit that this may be somewhat awkward. Obviously

14

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 14 04/10/2013 15:43

P R e s e n t i n g t h e B u d d h a : i m a g e s , c o n v e n t i o n s , a n d s i g n i f i c a n c e i n e a R ly i n d i a n B u d d h i s m

strictly speaking, of bodhisattva images, not Buddha images – was absence of fear). Since no Indic or Tibetan version is extant, it

a representation of Śākyamuni as a bodhisattva, that is, in the is not possible to determine what was used as the original word

pre-enlightenment stage (Rhi 1994). In this case, the bodhi tree for anwei. Considering that anwei was often a translation of

could have simply signified the ultimate goal of the bodhisattva’s āśvāsa or related words (Hirakawa 1997: 374b), the original Indic

pursuit; or, if one is tempted to read the scene in terms of greater may not have been abhaya. This means that by the time of the

narrative spirit, it could have marked the bodhisattva being at the Sūtrālaṃkāra there was a similar conception but the designation

moment just prior to enlightenment. abhaya-mudrā did not yet exist. In the Chinese textual tradition,

10. For example, the relevant part on a famous image dedicated by which is easy to look up through the Taishō canon, the word is

the monk Bala at Sārnāth in the third year of Kaniṣka (129/130 not found in any text translated before the mid-seventh century,

CE) reads: ‘bodhisatvo chatrayaṣṭi ca pratiṣṭāpito bārāṇasiye when it first appears in a text translated in 653, the Guanzizai

bhagavato caṃkame’ ([namely, an image of] the bodhisattva pusa suixinzhou jing (T1103, 18: 460a, 465c; trans. Zhitong, 653).

and an umbrella with a post, erected at Vārāṇasī, at the place The creation of the term or its regular usage in the Buddhist

where the Blessed One used to walk) (reading and translation context would not have appeared earlier than then.

based on Vogel 1908: 176–7 but with slight modification, cf. 17. For the western parallels, L’Orange 1953: 139–97, cf. Saunders

Tsukamoto 1996: Sārnāth 4; for the image, Sharma 1995: fig. 84). 1960: 55–6. For the examples from Parthian Iran, Ghirshman

For other examples, one from Kauśāmbī, Chandra 1970: no. 85 1962: figs 36, 100, 104–106, 110. Royal portraits from Parthia

and Tsukamoto 1996: Kosam 2; one from Śrāvastī, Sharma 1995: show remarkable similarities to Buddha images from Gandhāra,

fig. 130 and Tsukamoto 1996: Saheṭh-Maheṭh 2. not only in the positioning of the hand but also in the strict

11. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: nos. 52, 53. frontality of the statues. In terms of its establishment, the

12. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: no. 222. This Buddha is identified as distinctive Parthian hand gesture could have slightly preceded

the Buddha receiving the offering of the previous incarnation the abhaya-mudrā of Gandhāran Buddhas, or alternatively it was

of Aśoka in comparison with narrative depictions of the theme a parallel development in Iran and northern India. A slightly

(Ingholt and Lyons 1957: nos. 110, 111). different gesture with the right had stretched with the palm

13. Rhi 1999: pl. 52. Besides this sole example probably from the facing outward is also found in Āndhra as early as the second

Peshawar valley, several examples are known from the Kapiśi century BCE (Coomaraswamy 1929).

valley in Afghanistan. 18. According to Dale Saunders, providing Toganoo Shōun as a

14. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: nos. 87, 88, 89; Kurita 2003: I, fig. 312. reference, ‘Traditionally, the position of the hand in the semui-in

Buddha images that portray this theme are relatively small in [abhaya-mudrā] derives from the legend of the malevolent

size. Besides these, images of Dīpaṅkara Buddha – thus, not Devadatta, who, wishing to hurt the Buddha, caused an elephant

Śākyamuni – giving a prediction to a previous incarnation of to become drunk’ (Saunders 1960: 58). However, Toganoo simply

Śākyamuni, identifiable by a small prostrating figure at the right mentions, citing three textual sources of the theme, that the

foot of the Buddha, are known from the Kapiśi valley (Auboyer Buddha raised the right hand and stretched his five fingers (a

1968: pl. 42). In this paper, I provide – in addition to Ingholt and gesture corresponding to abhaya-mudrā) in subduing the drunken

Lyons 1957 – Kurita 2003 (2 vols) as references for Gandhāran elephant, as a natural act in such incidents (Toganoo Shōun 1932:

works that cannot be illustrated because Kurita’s book is easily 483), and neither Toganoo’s remark nor the textual descriptions

available and also includes objects from outside Pakistan. he has in mind (T211, 4: 596a; T1545, 27: 322b; T1546, 27: 429a)

Nonetheless, my citations are restricted to pieces dependable in have anything to do with the ‘derivation’ of the gesture from a

authenticity since, as many experts agree, the book contains a narrative, which clearly has no historical basis. Alfred Foucher

number of dubious pieces, especially among those from private notes that in Gandhāran representations of the Buddha’s life,

collections, unlike Ingholt and Lyons 1957, which consists mainly abhaya-mudrā was used for various purposes in multiple themes

of works from Pakistan, long before the forgery became such a (Foucher 1918: 326), a fact that Saunders also admits (Saunders

serious problem in the Gandhāran art market and scholarship. 1960: 15, 43). Saunders also suggests that ‘in Gandhāran art, one

15. Buddha images in Āndhra are usually in the standing pose, may already notice the habit of assigning certain mudrā to certain

showing abhaya-mudrā, with little variation in detail. SBDT 2000: personages, doubtless in order to differentiate among the various

pl. 121, figs 112, 123. There must have been seated images such as Buddhas and bodhisattvas’; ‘already in Gandhāra gestures had

those carved in large relief panels featuring a stupa, although few begun to designate specifically certain Buddha’ (Saunders 1960:

examples are known in actual images, and they invariably show 15, 44). These observations of course are not acceptable based on

abhaya-mudrā. For those carved as part of larger reliefs, Knox the evidence we have, and Saunders also admits this, calling it the

1992: nos. 69, 72 (standing Buddhas), 52, 53, 70, 71, 83, 85, 86, 131 ‘uncertainty of Gandhāran usage’ (Saunders 1960: 15–16).

(seated Buddhas). 19. Bhattacharyya 2002: no. 263; Foucher 1905: fig. 280.

16. It is not clear when the term abhaya-mudrā (shiwuweiyin in 20. It may be noted that in Gandhāran Buddhist imagery, abhaya-

Chinese) was first used in the Buddhist textual tradition. In the mudrā Buddhas are relatively small in number, and few of them

Sūtrālaṅkāra attributed to Aśvaghoṣa and preserved only in were made during the most productive period (cf. Rhi 2008). On

Chinese translation by Kumārajīva, a thief who was saved from the other hand, in Mathurā, Buddhas of this type are relatively

punishment through the generosity of the deeply devout Buddhist more common, although the overall number of independent

king says: ‘Why do the artisans of the world, with exquisite skills images from this region is much smaller than that from

and sacred heart, represent an image [of the Buddha] as raising Gandhāra.

the right hand and showing the form of consolation? This is for 21. For other examples from Gandhāra: Foucher 1905: fig. 201;

one who has fear to remove the fear when seeing the image. How Ingholt and Lyons 1957: no. 63; Kurita 2003: I, figs 226, 229, 235.

numerous would those saved by the Buddha have been, when he For examples from Mathurā: Sharma 1995: figs 106, 168, 170.

was in this world? I just met great suffering and misfortune, but 22. See Foucher’s remark in note 18 above.

the image saved me from it’ (T201, 4: 263b; Huber 1908: 34–5; 23. See for example Ingholt and Lyons 1957: figs XI.4, XII.1, XII.3, XII.4;

cf. Foucher 1918: 327–8; Saunders 1960: 59). This passage clearly Kurita 2003: II, figs 229, 260, 264. There is only one example in

shows the understanding of the Buddha image with the raised which a narrative theme, the Buddha’s meditation in Indra’s cave,

right hand as an iconographic type. In characterising the raised is carved on the pedestal (Ingholt and Lyons 1957: fig. XII.2).

right hand, the text uses the phrase anweixiang (the form of 24. For the relationship of the three seated Buddha types to five visual

consolation or appeasement) instead of shiwuwei (granting the types, see Rhi 2008: 49, 53, 61, 64, 71.

15

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 15 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

25. The Buddha is inscribed with the year 36. The year must belong rather than zhuanfalunyin with the character yin (mudrā), it

to the Kaniṣka era, but the 36th year of the era is obviously too seems likely that the name for the mudrā was established by that

early for the image, which shows a much more developed stage time.

in Mathurā than examples from the first half of the first century 40. Lamotte 1981; Tsukamoto 1979; Rhi 1991: 110–22.

of the era, which was dominated by the kapardin type. It seems 41. Rhi 2003: 168–71.

more reasonable to think that it dates from a century later, the 42. Zimmer 1946: 17, 61, 90; Bailey 1983: 90–92.

136th year of the Kaniṣka era (with the application of the so-called 43. T291, 10: 596c–597b.

‘omitted-hundred’ theory) or the 36th year of the second Kaniṣka 44. The two later Chinese translations appear as part of the

era, which started around the 98th year of the original Kaniṣka Avataṃsaka-sūtra: Buddhabhadra’s translation (420), T278, 9:

era (following John Rosenfield’s suggestion). Cf. Sharma 1995: 613b–614a; Śikṣānanda’s translation (712), T279, 10: 264a–c (cf.

198–9. Cleary 1993: 976–8); see also a Tibetan translation, P.761 Śi 84a4-5

26. Whereas there is no precisely datable piece among dhyāna-mudrā (I am grateful to Kim Seongcheol for helping me check this part

Buddhas from Gandhāra, the dharmacakra-mudrā Buddha in the Tibetan translation).

appears at the centre of a triad inscribed with the year 5 (Czuma 45. In the Tathāgatotpattisambhavanirdeśa passage cited above, the

1985: no. 109; Kurita 2003: I, pl. P3-VIII). Whether it should be comparison to Brahmā is not clearly stated, though I believe that

dated to the fifth year of the Kaniṣka era or a century later, as with there is an allusion to the cosmogonic myth of Brahmā on a lotus.

some Mathurā Buddhas, has been debated. The former date seems However, a passage in a text called Samyuktāvadāna (Zapiyujing)

too early. in Chinese translation (by Daolüe, early fifth century) speaks

27. One (datable to the fourth century) is in the Lucknow State explicitly of the myth by mentioning both Brahmā and Viṣṇu,

Museum (Sharma 1995: 201 and fig. 123), and the other (early fifth from whose navel the lotus sprouts. It says at the end: ‘Because

century) in the Cleveland Museum of Art (acc. no. 1973.214). In this Brahmā king has removed covetousness, anger, and delusion

the earlier example in Lucknow, the hands are lost, with only their without remainder, it is said that if a person practices meditation

traces visible on the chest. Sharma questions the identification and pure conduct and cuts and removes sensuous desire, the

of the hand gesture as dharmacakra-mudrā, instead suggesting conduct is called the brahmā path. The Buddha’s turning of the

the possibility of abhaya-mudrā: ‘The left hand was raised up to dharma wheel is called [the turning of] the brahmā wheel. Because

support the hem of the drapery in the parallel position to the this Brahmā king sits on a lotus, all the Buddhas, following the

right hand in the protection pose.’ However, it seems impossible custom of the world, also sit cross-legged on a lotus and preach

that the traces were of the hands of abhaya-mudrā. on the six pāramitās’ (T207, 4: 529b).

28. Lohuizen-de Leeuw 1981. 46. For the Indic equivalent for chikenin, or the mudrā that appears for

29. Carter 1988: 23–4. Vairocana or Mahāvairocana in the esoteric Buddhist iconography,

30. For the Entreaty to Preach (featuring the dhyāna-mudrā Buddha), M.-Th. de Mallmann refers to bodhyagrī (‘la “fine pointe” de Éveil’

Foucher 1905: fig. 213; Ingholt and Lyons 1957: no. 73; Kurita or the pinnacle of enlightenment), while considering bodhyaṅgī

2003: I, fig. 266. For the Indraśailaguhā, Ingholt and Lyons 1957: (the member of enlightenment) as incorrect (Mallmann

nos. 128–35; Kurita 2003: I, figs 333–5, 337, 340. 1975: 33, 393). Susan and John Huntington call it bodhyaṅgī

31. For depictions of the Entreaty to Preach (featuring the abhaya- (Huntington 1985: 402–3). Saunders gives, with hesitation,

mudrā Buddha), Ingholt and Lyons 1957: nos. 70–72. vajra-mudrā, jñāna-mudrā and bodhaśrī-mudrā (Saunders

32. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: nos. 130, 131; Kurita 2003: I, fig. 334. 1960: 102). Frederick Bunce presents the same terms cited by

33. Rhi forthcoming. Saunders as corresponding to chikenin, but his description and

34. Śāriputraparipṛcchā (Sherifuwenjing), T1465, 24: 901a; BD: 4969b; illustration actually show that he means by them what is known

MBD: 4535b–4536a. as vitarka-mudrā or vyākhyāna-mudrā (Bunce 1997: 132 and fig.

35. Cf. Foucher 1918: 328. I can recall four examples of the First 342). In the textual tradition, bodhyagrī seems best documented

Sermon depicted with the dharmacakra-mudrā Buddha (ruling in numerous texts such as the Sarvadurgatipariśodhanatantra

out dubious pieces): two in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, and the Mañjuśrīmulakalpa, while bodhyaṅgī is also found in

Berlin (I577, I588), one in the National Museum, Karachi, and one the Sādhanamālā and Niṣpannayogāvalī (both in Benoytosh

formerly in the Islamabad Museum. For the sole extant depiction Bhattacharya’s editions). What these terms actually meant in

of the presentation of the first Buddha image, see Ingholt and relation to visual images is of course debatable. I thank Alexander

Lyons 1957: no. 125. Other examples of the dharmacakra-mudrā von Rospatt for the information about the textual tradition.

Buddha used in different or unknown themes include a depiction 47. Getty 1914: 168; Huntington 1984: 155–7. Citing Getty’s idea,

of the conversion of the nāga Elapatra (Museum Volkenkunde, Saunders admits that the two are ‘sculpturally very close’, but

Leiden), two reliefs in the Peshawar Museum (Ingholt and Lyons he expresses scepticism about the derivation of the Japanese

1957: no 165A; Kurita 2003: I, fig. 559), and a relief in the Lahore chikenin from the Gandhāran dharmacakra-mudrā (Saunders

Museum (unpublished). 1960: 103).

36. For an overview of the issue, Rhi 1991; for the Great Miracle 48. Williams 1975: fig. 13c.

theory, Foucher 1909; for the Amitābha theory, Higuchi 1950 49. Donaldson 2001: I, 106; II, fig. 144. Donaldson calls this hand

and Huntington 1980. gesture bodhyaṅgī-mudrā, without pointing out its resemblance

37. For the most recent attempt on the Amitābha theory, Harrison to the Gandhāran dharmacakra-mudrā or its difference from the

and Luczanits 2011. proper mudrā by the same name of Mahāvairocana.

38. The term dharmacakra-mudrā was probably first used for 50. Actual examples from India are extremely rare. Bak Hyeongguk

Gandhāran Buddhas by Foucher in its French translation ‘la cites a relief figure carved in Cave 12 at Ellora (eighth century)

mudrā qui fait tourner la roué de loi’ (Foucher 1918: 328, cf. (Bak 2001: 144 and fig. 62). Another example is a small metal

Foucher 1900: 68, which explains the dharmacakra-mudrā of image from Nālandā (eleventh century), which actually holds

the middle Gangetic type). a vajra as well (Huntington 1985: fig. 18.18). For lesser-known

39. The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, who reached Mṛgadāva (Deer examples from Java and Korea compared with those from Japan

Garden) at Sārnāth in the early 630s, describes a Buddha image and Tibet, Fontein 1990: pl. 68; Kim 2007: 91–9.

in the main shrine as ‘taking the posture of turning the dharma 51. The following discussions of the scenes carved on the pedestals

wheel’ (T2087, 51: 905b, cf. Beal 1884: 46). Although Xuanzang of Buddha images are based on my own database of works

uses the phrase zhuanfalunshi with the character shi (posture) dependable in authenticity. I will cite only representative

16

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 16 04/10/2013 15:43

P R e s e n t i n g t h e B u d d h a : i m a g e s , c o n v e n t i o n s , a n d s i g n i f i c a n c e i n e a R ly i n d i a n B u d d h i s m

examples or readily consultable examples. For seated abhaya- Beal, S. (tr). 1884. Si-yu-ki: Buddhist Records of the Western World, vol.

mudrā Buddhas carved with rosettes or lotuses on the pedestals, 2. London: Trübner & Co.

see Ingholt and Lyons 1957: fig. XII.3; Zwalf 1996: II, pl. 20; Bhattacharyya, D.C. (ed). 2002. Gandhāra Sculpture in the Government

Kurita 2003: II, fig. 264. These motifs also appear commonly in Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh. Chandigarh: Chandigarh

the pedestals of standing Buddhas. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: fig. Museum and Art Gallery.

XVII.4, nos. 195, 209, 215, 225; Kurita 2003: II, fig. 222. Boisselier, J. 1975. The Heritage of Thai Sculpture. New York and Tokyo:

52. The motif of three rosettes appears distinctively with the seated Weatherhill.

abhaya-mudrā Buddha in the two scenes immediately following Boucher, D. 1991. ‘The pratītyasamutpādagāthā and its role in the

the Enlightenment among 13 reliefs decorating the Sikri stupa, medieval cult of the relics’, Journal of the International Association

while the Enlightenment itself is not represented in this stupa. of Buddhist Studies 14(1): 1–27.

Ingholt and Lyons 1957: nos. 68 (Offering of Four Bowls), 70 Bunce, F.W. 1997. A Dictionary of Buddhist and Hindu Iconography. New

(Entreaty to Preach). Delhi: D.K. Printworld.

53. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: fig. XIII.3, no. 234; Zwalf 1996: II, pl. 32; Carter, M. 1988. ‘A Gandharan bronze Buddha statuette: its place in the

Bhattacharyya 2002: figs 615, 616. evolution of the Buddha image in Gandhara’, Mārg 39(4): 21–38.

54. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: figs XVI.1, XVI.2, nos. 248–249, 251; Zwalf Chandra, P. 1970. Stone Sculpture in the Allahabad Museum: A

1996: II, pls 24, 26; Kurita 2003: II, figs 223, 240. Descriptive Catalogue. Poona: American Institute of Indian Studies.

55. The identification of this type as Prince Siddhārtha’s first Cleary, T. (tr). 1993. The Flower Ornament Scripture: A Translation of the

meditation is based on a ploughing scene carved on the pedestal Avatamsaka Sutra. Boston and London: Shambala.

of an image in the Peshawar Museum (Ingholt and Lyons 1957: no. Coomaraswamy, A.K. 1929. ‘A royal gesture; and some other motifs’, in

284). For other examples, Ingholt and Lyons 1957: no. 318; Kurita Feestbundel uitgegeven door het Koninklijk Bataviaasch Genootschap

2003: II, fig. 124. For narrative depictions of the First Meditation, van Kunsten en Wetenschappen bij gelegenheid van zijn 150 jarig

Ingholt and Lyons 1957: no. 36. For similar seated bodhisattvas bestaan, 1778–1928, vol. 1. Weltevreden: G. Kolff, 57–61.

from Mathurā, Sharma 1995: figs 70, 115. Czuma, S.J. 1985. Kushan Sculpture: Images from Early India. Cleveland,

56. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: nos. 233, 236 (dhyāna-mudrā Buddhas), OH: Cleveland Museum of Art.

206 (standing Buddha); Kurita 2003: II, fig. 199 (standing Donaldson, T.E. 2001. Iconography of the Buddhist Sculpture of Orissa, 2

Buddha). vols. New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts.

57. Mahāvastu, Jones 1952: 195; Buddhacarita, Johnston 1936: 184; Fontein, J. 1990. The Sculpture of Indonesia. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Lalitavistara, Goswami 2001: 246. Foucher, A. 1900. Étude de l’iconographie bouddhique de l’Inde d’après

58. For the Four Encounters, there is only one extant depiction from des documents nouveaux. Paris: Ernest Leroux.

Gandhāra: Kurita 2003: I, fig. 135. Foucher, A. 1905. L’Art gréco-bouddhique du Gandhâra, vol. 1. Paris:

59. For seated bodhisattvas in the meditation pose, Ingholt and Lyons Imprimerie nationale.

1957: no. 318; Kurita 2003: II, fig. 124. Foucher, A. 1909. ‘Le grand miracle du Bouddha à Çrâvastî’, Journal

60. Schopen 2005: 128. asiatique 13 (Jan–Feb): 5–78.

61. Schopen 2005: 129–34. Foucher, A. 1918. L’Art gréco-bouddhique du Gandhâra, vol. 2, pt. 1. Paris:

62. T1435, 23: 352a, 355a; this translation is based on Soper 1950: 140a, Imprimerie nationale.

with significant modification. In the original text, the phrase I Getty, A. 1914. The Gods of Northern Buddhism. Oxford: Clarendon

translate here as ‘an image of the time [when the Buddha was] Press.

a bodhisattva’ (pusashixiang) literally reads ‘an image of the Ghirshman, R. 1962. Persian Art: The Parthian and Sassanian Dynasties,

attendant bodhisattva’ as Soper translates it. The difference in 249 BC–AD 651, S. Gilbert and J. Emmons (trs). New York: Golden

understanding this phrase depends on the character shi. The shi Press.

(with the radical ‘human’) in the original has the meaning of GNB 1970. Genshoku nihon no bijutsu (Japanese art in colour), vol. 9:

‘attendant’, but, following Lin Li-kouang’s suggestion (Lin 1949: chūsei jiin to kamakura chōkoku (Medieval temples and Kamakura

97 and n. 2), I believe that it was a scribal error for the shi (with sculptures). Tokyo: Shogakukan.

the radical ‘sun’) meaning ‘time’, which makes better sense; Rhi Goswami, B. (trs) 2001. Lalitavistara. Kolkata: The Asiatic Society.

1994: 221. GSRB 1988. The Grand Exhibition of Silk Road Civilizations: The Route

63. Ingholt and Lyons 1957: nos. 63, 66; Kurita 2003: I, figs 226, 227, of Buddhist Art. Nara: Nara National Museum.

229, 235; Sharma 1995: figs 168, 170, 175. Harrison, P. and Luczanits, C. 2011. ‘New light on (and from) the

64. Four reliefs in the Freer-Sackler Gallery in Washington, DC: Kurita Mohammed-Nari stele’, unpublished paper presented at the

2003: I, figs 31, 226, 280, 483. Conference on Pure Land Buddhism at Otani University, Kyoto,

65. Sharma 1995: fig. 168. November 2011.

66. See note 48 above. Higuchi, T. 1950. ‘Amida sanzonbutsu no genryū’ (‘The origin of the

67. Leoshko 2000/2001. Amitābha triad’), Bukkyō geijutsu 7: 108–13.

Hirakawa, A. 1997. Bukkyō kanbon daijiten (Buddhist Chinese-Sanskrit

dictionary). Tokyo: Reiyukai.

Huber, É. (tr.) 1908. Sûtrâlaṃkâra. Paris: Ernest Reloux.

Huntington, J.C. 1980. ‘A Gandhāran image of Amitāyus’ Sukhāvatī’,

Annali dell’Istituto Orientale di Napoli 40 (n.s. 30): 652–72.

References Huntington, J.C. 1984. ‘The iconography and iconology of Maitreya

images in Gandhāra’, Journal of Central Asia 7(1): 133–78.

Auboyer, J. 1968. The Art of Afghanistan, P. Keebone (tr.). Feltham: Paul Huntington, S.L. 1985. The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu and

Hamlyn. Jain. Tokyo: Weatherhill.

Bailey, G. 1983. The Mythology of Brahmā. Delhi: Oxford University Ingholt, H. and Lyons, I. 1957. Gandhāran Art in Pakistan. New York:

Press. Pantheon Books.

Bak, H. 2001. Vairochanabutsu no zuzōgakuteki kenkyū (Iconographical Johnston, E.H. 1936. The Buddhacarita, or, Acts of the Buddha, part 2

study of Vairocana Buddha). Tokyo: Hōzōkan. (translation). Lahore: University of the Punjab.

BD -- Bukkyō daijii (Dictionary of Buddhist vocabulary), Ryūkoku Jones, J.J. (tr.) 1952. The Mahāvastu, vol. 2. London: Luzac & Co.

University (ed), 2nd edn. Tokyo: Fuzanbō, 1936.

17

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 17 04/10/2013 15:43

Juhyung Rhi

Kim, L. 2007. Buddhist Sculpture of Korea. Elizabeth, NJ, and Seoul: Rhi, J. 2010. ‘Does iconography really matter?: the iconographic

Hollym. specification of Buddha images in pre-Esoteric Buddhist art’,

Knox, R. 1992. Amarāvatī: Buddhist Sculpture from the Great Stūpa. unpublished paper presented at the conference New Research in

London: British Museum Press. Buddhist Sculpture, Victoria and Albert Museum, November 2010.

Kurita, I. 2003. Gandhāran Art, rev. edn, 2 vols. Tokyo: Nigensha. Rhi, J. forthcoming. ‘Vision in the cave, cave in the vision: the

Lamotte, É. 1981. ‘Lotus et Buddha supramondain’, Bulletin de l’École Indraśailaguhā in textual and visual traditions of Indian

Française d’Extrême-Orient 69: 31–44. Buddhism’, in Buddhism across Asia, T. Sen (ed). Singapore: Institute

Leoshko, J. 2000/2001. ‘About looking at Buddha images in eastern of Southeast Asian Studies.

India’, Archives of Asian Art 52: 63–82. Saunders, E.D. 1960. Mudrā: A Study of Symbolic Gestures in Japanese

Lin, Li-kouang 1949. L’Aide-mémoire de la vraie loi (Saddharma- Buddhist Sculpture. New York: Pantheon Books.

smṛtyupasthāna-sūtra). Paris: Adrien Maisonneuve. SBDT 2000. Sekai bijutsu daizenshū tōyōhen (New History of World

Lohuizen-de Leeuw, J.E. van. 1981. ‘New evidence with regard to the Art: Asia), vol. 13: India (1). Tokyo: Shogakukan.

origin of the Buddha image’, in South Asian Archaeology 1979, H. Schopen, G. 2005. ‘On sending the monks back to their books: cult

Härtel (ed.). Berlin: Museum für Indische Kunst, 377–400. and conservatism in early Mahāyāna Buddhism’, in Figments and

L’Orange, H.P. 1953. Studies on the Iconography of Cosmic Kingship in Fragments of Mahāyāna Buddhism in India, G. Schopen. Honolulu,

the Ancient World. Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co. HI: University of Hawai’i Press, 108–53.

Luce, G.H. 1969. Old Burma, Early Pagan, vol. 1. Locust Valley, NY: Sharma, R.C. 1995. Buddhist Art: Mathura school. New Delhi: Wiley

Artibus Asiae and the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University. Eastern and New Age International.

Mallmann, M.-T. de 1975. L’Introduction à l’iconographie du tântrisme Soper, A.C. 1950. ‘Early Buddhist attitudes toward the art of painting’,

bouddique. Paris: Adrien Maisonneuve. Art Bulletin 35(2): 147–51.

Miyaji, A. 1992. Nehan to miroku no zuzōgaku (The iconography of T – Taishō Buddhist canon (Taishō shinshū daizōkyō, Tokyo: Taishō

the mahāparinirvāṇa and Maitreya). Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan. issaikyō kankōkai, 1924–1934), number, volume, page.

MBD – Mochizuki bukkyō daijiten (Mochizuki Buddhist dictionary), Toganoo, S. 1932. Mandara no kenkyū (Study of maṇḍalas). Koyasan:

Mochizuki Shinkō (ed.), 2nd edn (rev. Tsukamoto Zenryū). Kyoto: Koyasan University Press.

Sekai seiten kankō kyōkai, 1954–63. Tsukamoto, K. 1979. ‘Rengejō to rengenza’ (‘The birth on the lotus and

P – Tibetan Buddhist canon Peking edition (reprint, Tokyo, Seizō the lotus seat’), Indogaku bukkyōgaku kenkyū 28(1): 1–9.

daizōkyō kenkyūkai, 1955–1961), number, box, page. Tsukamoto, K. 1996. Indo bukkyō himei mokuroku I: Text, note, wayaku

PGC 2002. Pakisutan gandāra chōkokuten (Exhibition of Gandhāran (A comprehensive study of the Indian Buddhist inscriptions, part

sculpture). Tokyo: NHK Promotion. 1: text, notes, and Japanese translation). Kyoto: Heirakuji shoten.

Rhi, J. 1991. Gandhāran Images of the Śrāvastī Miracle: An Iconographical Vogel, J.Ph. 1908. ‘Epigraphical discoveries at Sarnath’, Epigraphia

Assessment, PhD dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. Indica 8: 166–79.

Rhi, J. 1994. ‘From bodhisattva to Buddha: the beginning of iconic Williams, J.G. 1975. ‘Sārnāth Gupta steles of the Buddha’s life’, Ars

representation in Buddhist art’, Artibus Asiae 54(3/4): 207–25. Orientalis 10: 171–92.

Rhi, J. (ed.) 1999. Kandara misul (Gandhāran art) (exhibition Zimmer, H. 1946. Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization.

catalogue). Seoul: Seoul Arts Centre. New York: Pantheon Books.

Rhi, J. 2003. ‘Early Mahāyāna and Gandhāran Buddhism: an assessment Zwalf, W. 1996. A Catalogue of Gandhāra Sculpture in the British

of visual evidence’, The Eastern Buddhist 35(1&2): 152–89. Museum, 2 vols. London: British Museum.

Rhi, J. 2008. ‘Identifying several visual types in Gandhāran Buddha

images’, Archives of Asian Art 54: 43–85.

18

BAF-01-Rhi.indd 18 04/10/2013 15:43

Você também pode gostar

- Śrī Si Ha's Ultimate Upadeśa - HalkiasDocumento14 páginasŚrī Si Ha's Ultimate Upadeśa - HalkiasAnonymous udbkKpS38100% (1)

- The Mahayana Deconstruction of TimeDocumento12 páginasThe Mahayana Deconstruction of TimeAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- A Richness of Detail Sangs Rgyas Gling PDocumento29 páginasA Richness of Detail Sangs Rgyas Gling PAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Introduction Trans-Himalayas As Multista PDFDocumento42 páginasIntroduction Trans-Himalayas As Multista PDFAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Sacred Economies of Kalimpong - The Eastern Himalayas in The Global Production and Circulation of Buddhist Material CultureDocumento19 páginasSacred Economies of Kalimpong - The Eastern Himalayas in The Global Production and Circulation of Buddhist Material CultureAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Frictions in Trans Himalayan StudiesDocumento15 páginasFrictions in Trans Himalayan StudiesAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Adjusting LivelihoodDocumento23 páginasAdjusting LivelihoodAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Garland of ViewsDocumento7 páginasGarland of Viewsmauricio_salinas_2Ainda não há avaliações

- Towards A Comparative History of BorderlandsDocumento32 páginasTowards A Comparative History of BorderlandsAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Trans-Himalayan Buddhist Secularities Si PDFDocumento19 páginasTrans-Himalayan Buddhist Secularities Si PDFAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö's Prophecy of Things To ComeDocumento24 páginasJamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö's Prophecy of Things To ComeAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- He VajraDocumento2 páginasHe VajraAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Buddhist Books On Trans-HimalayanDocumento21 páginasBuddhist Books On Trans-HimalayanAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Tibetan Wine ProductionDocumento23 páginasTibetan Wine ProductionAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Contested Modernities PlaceDocumento23 páginasContested Modernities PlaceAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Miller Gsas - Harvard 0084L 10880Documento357 páginasMiller Gsas - Harvard 0084L 10880Ilya Ivanov100% (1)

- Great Journeys in Little Spaces: Buddhist Matters in Khyentse Norbu's Travellers and MagiciansDocumento19 páginasGreat Journeys in Little Spaces: Buddhist Matters in Khyentse Norbu's Travellers and MagiciansAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Dependent Origination in the CaṇḍamahāroṣaṇatantraDocumento9 páginasDependent Origination in the CaṇḍamahāroṣaṇatantraAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Ai Khanum Reconstructed Lecuyot 2007Documento12 páginasAi Khanum Reconstructed Lecuyot 2007Anonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Sri SimhaDocumento5 páginasSri SimhaAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- On Personal Protective Deities Go Bai LH PDFDocumento21 páginasOn Personal Protective Deities Go Bai LH PDFAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Halkias - One Hundred Peaceful and Wrathful DeitiesDocumento30 páginasHalkias - One Hundred Peaceful and Wrathful DeitiesAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- AbarisDocumento6 páginasAbarisAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- John Stanley, David R. Loy, Gyurme Dorje A Buddhist Response To The Climate Emergency PDFDocumento314 páginasJohn Stanley, David R. Loy, Gyurme Dorje A Buddhist Response To The Climate Emergency PDFAnonymous udbkKpS38100% (1)

- Phun-Tshog Wangdan A Catalogue of Tibeta PDFDocumento23 páginasPhun-Tshog Wangdan A Catalogue of Tibeta PDFAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Self Mumified Buddhas in JapanDocumento24 páginasSelf Mumified Buddhas in JapanAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Hippocrates / With An English Translation by W. H. S. Jones - Vol.1Documento452 páginasHippocrates / With An English Translation by W. H. S. Jones - Vol.1kuszabaAinda não há avaliações

- Dialnet EpimenidesOfCrete PDFDocumento17 páginasDialnet EpimenidesOfCrete PDFAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- The Highland Vinaya Lineage A Study of A PDFDocumento38 páginasThe Highland Vinaya Lineage A Study of A PDFAnonymous udbkKpS38Ainda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)