Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Infected Closed Fracture: A Rare Case Report

Enviado por

Rizaldy DanupoyoDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Infected Closed Fracture: A Rare Case Report

Enviado por

Rizaldy DanupoyoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

1

C OPYRIGHT Ó 2012 BY T HE J OURNAL OF B ONE AND J OINT S URGERY, I NCORPORATED

Infection in Closed Fractures

A Case Report and Literature Review

Christopher Kim, MD, and Ted V. Tufescu, MD, FRCSC

Investigation performed at the Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

I

nfection after a closed fracture is rare. Whereas open frac- the anesthesiologist noted that the patient had a fever of 39°C.

tures are considered contaminated, closed fractures are as- Intraoperatively, a small amount of purulent liquid was discovered

sumed to be uncontaminated and have an extremely low risk in the medial suprapatellar area. The surrounding soft tissue also

of infection. We report on a previously healthy adult patient who

presented acutely with an infected, closed patellar fracture. The

patient was informed that data concerning her case would be

submitted for publication, and she provided consent.

Our review of the literature has identified several reports

of osteomyelitis in closed fractures1-12. These were generally pe-

diatric cases1,3,5,8,9-11 or cases in immunocompromised adults2,11,12.

Our patient was an immunocompetent adult. We found only five

cases of osteomyelitis after closed fractures in immunocompetent

adults4,6,7,9. In two of the cases, the patients presented with mul-

tiple severe injuries and associated complications that could have

served as a source for hematogenous spread of bacteria4,7. In all

five cases, it took several weeks to months for an infection to

present at the closed fracture site4,6,7,9. Our patient presented

acutely with an isolated closed injury with no apparent source

for infection.

The pathogenesis of an infection after a closed fracture is

an area of interest and research. First, it appears that healthy

tissue and body fluids are not bacteria-free, and that an open

wound is not the only source for a bacterial infection13-17. Second,

mechanisms have been described that allow such indwelling

bacteria to ‘‘home’’ to sites of closed injury16-18. Third, it has been

suggested that local changes after a closed injury can increase

susceptibility to infection13,19. The purpose of this report is to

briefly review these issues and increase awareness of this rare

event.

Case Report

A previously healthy thirty-one-year-old woman sustained an

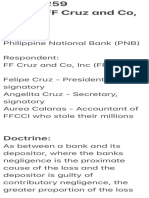

isolated left patellar fracture (Fig. 1) after falling down a

flight of stairs. The patient was afebrile without symptoms of

infection. Physical examination revealed moderate swelling with-

out open wounds or abrasions. Two days after injury, the patient Fig. 1

was taken to the operating room for fracture fixation. At this time, Lateral knee radiograph of the closed transverse patellar fracture.

Disclosure: None of the authors received payments or services, either directly or indirectly (i.e., via his or her institution), from a third party in support of

any aspect of this work. None of the authors, or their institution(s), have had any financial relationship, in the thirty-six months prior to submission of this

work, with any entity in the biomedical arena that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what is written in this work. Also, no

author has had any other relationships, or has engaged in any other activities, that could be perceived to influence or have the potential to influence what

is written in this work. The complete Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest submitted by authors are always provided with the online version of the

article.

JBJS Case Connect 2012;2:e44 d http://dx.doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.CC.L.00008

2

J BJ S C A S E C O N N E C T O R INFECTION IN CLO S E D FR AC T U R E S

V O LU M E 2 N U M B E R 3 A U G U S T 22, 2 012

d d

tissues, including the soft tissues, tissue fluids, lymphatics, and

lymph nodes13-17. Skin microorganisms can penetrate the epi-

dermis to translocate and eventually reside in deeper tissues18.

For example, foot microorganisms may penetrate the skin

through microinjuries or skin fissuring. They may use the

lymphatics and blood circulation to eventually settle within the

perivascular spaces and lymph nodes18. The propensity of pre-

patellar bursitis to become infected is also well recognized. Ap-

proximately 80% of cases are caused by Staphylococcus aureus20.

It is believed that such factors as minor trauma, humidity, and

skin fissuring all contribute to the direct inoculation of normal

skin bacteria into the superficial bursa20. The fluid collection or

hematoma from a patellar fracture is in close proximity to the

skin, and it is reasonable to consider a similar mechanism of

infection in the setting of local trauma. In any case, healthy,

noninjured tissue and body fluids are not bacteria-free. These

bacteria do not evoke a host response, perhaps because the

bacterial load remains below the threshold of an inflammatory

response.

It has been suggested that the effects of closed trauma

allow such indwelling bacteria to ‘‘home’’ to the site of injury.

Szczesny et al. hypothesized that bacteria residing in local lymph

and lymph nodes may translocate to an acute closed fracture

site16,17. They suggested that a fracture results in the activation of

the local lymphoid tissue, resulting in dilated lymphatics, en-

larged lymph nodes, and mobilization of cells within the nodes17.

Although the nature of this response is unknown, it provides a

possible mechanism for the movement of bacteria to the fracture

site. It has also been suggested that bacteria that survive and

reside within host phagocytic cells may be transported to dam-

Fig. 2 aged tissue during the inflammatory phase18. It is also possible

Lateral knee radiograph following fixation of the patellar fracture with the that damage to local soft tissue contributes to the direct inocu-

tension band wiring technique. lation of indwelling bacteria to the fracture site.

Posttraumatic infection is related to the local changes

appeared to be infected on visual inspection. Wound swabs, tissue that occur to increase susceptibility to infection; local soft-

samples, and blood were collected for Gram stain and cultures. tissue trauma is a risk factor for posttraumatic infection13,19.

Thorough irrigation and debridement were performed. After It is believed that soft-tissue damage and its pathophysio-

internal fixation of the patella (Fig. 2), a Hemovac drain was logical consequences result in decreased resistance to bacte-

placed in the medial suprapatellar region, and the incision was rial load. Observations have shown that surgical treatment of

closed surrounding the drain. The patient was placed on in- closed fractures with severe soft-tissue injuries is associated

travenous (IV) cefazolin therapy postoperatively. with a higher risk of infection compared with closed fractures

On postoperative day three, the patient developed con- without severe soft-tissue injury21,22.

siderable cellulitis over the left knee. She was afebrile and the Our review of the literature revealed two main groups of

pain was controlled. Intraoperative cultures revealed b-hemolytic patients who developed infections after closed fractures. These

group-A streptococci from both the wound swab and tissue were either pediatric patients or immunocompromised adults.

samples. Blood culture specimens remained negative. The pa- The pediatric cases involved children who sustained a closed

tient was placed on IV ceftriaxone therapy for a total of six fracture and subsequently developed osteomyelitis after a short

weeks, followed by oral cefalexin therapy for another six weeks. period of nonoperative management1,3,5,8,9-11. These children

The infection subsided with this treatment, and the patient re- usually developed a remote infection shortly after their fracture,

gained full knee function. Implant removal was planned after full such as an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) or urinary

fracture consolidation. tract infection (UTI). These types of infections are described as

the possible source for spread of infection to the fracture site.

Discussion They were treated with antibiotics and had excellent outcomes.

W hen identifying infection in closed fractures with unper-

forated skin, we must consider the origin of the invading

bacteria. It has been reported that bacteria dwell in normal healthy

This was not the case with immunocompromised adults2,11,12 who

had reduced resistance to infection because of chronic con-

ditions, including diabetes, prolonged steroid use, or cancer.

3

J BJ S C A S E C O N N E C T O R INFECTION IN CLO S E D FR AC T U R E S

V O LU M E 2 N U M B E R 3 A U G U S T 22, 2 012

d d

Nonunion was not uncommon, and the outcome was generally flammatory response and cause an infection. It appears that

poor in these patients. properties of the invading bacteria and local host factors both

The diagnosis of infection at a closed fracture site is often play an important role. n

delayed. It is not unreasonable to suspect infection in patients

who continue to have symptoms of pain and swelling to the

fracture site after several weeks of immobilization. This is es-

pecially true in the pediatric patient with a history of a recent

remote infection, such as a URTI or UTI. In many cases, pa- Christopher Kim, MD

University of Manitoba, AD 420 – 720 McDermot Avenue,

tients are febrile and present with a warm, tender, and fluctuant Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3E 0T3 Canada.

fracture site. The belief that infection does not occur with E-mail address: umkim88@cc.umanitoba.ca

closed fractures may prove too simplified, as perforated skin

may not be the only source for bacterial invasion. Bacteria re- Ted V. Tufescu, MD, FRCSC

side in normal healthy tissue and fluids, including within the Health Sciences Centre, AD4 – 820 Sherbrook Street,

callus of a healing fracture16. We must question what the risk Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3A 1R9 Canada.

factors and mechanisms are for such bacteria to evoke an in- E-mail address: ttufescu@exchange.hsc.mb.ca

References

1. Aalami-Harandi B. Acute osteomyelitis following a closed fracture. Injury. 1978 13. Kälicke T, Schlegel U, Printzen G, Schneider E, Muhr G, Arens S. Influence of a

Feb;9(3):207-8. standardized closed soft tissue trauma on resistance to local infection. An experi-

2. Aluisio FV, Scully SP. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis of a closed frac- mental study in rats. J Orthop Res. 2003 Mar;21(2):373-8.

ture with chronic superinfection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996 Apr;(325): 14. Raasch W, Regunathan S, Li G, Reis DJ. Agmatine, the bacterial amine, is widely

239-44. distributed in mammalian tissues. Life Sci. 1995;56(26):2319-30.

3. Baharuddin M, Sharaf I. Acute haematogenous osteomyelitis: an unusual com- 15. Olszewski WL, Jamal S, Manokaran G, Pani S, Kumaraswami V, Kubicka U,

plication following a closed fracture of the femur in a child. Med J Malaysia. 2001 Lukomska B, Dworczynski A, Swoboda E, Meisel-Mikolajczyk F. Bacteriologic studies

Dec;56 Suppl D:54-6. of skin, tissue fluid, lymph, and lymph nodes in patients with filarial lymphedema.

4. Baskaran S, Nahulan T, Kumar AS. Close fracture complicated by acute Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997 Jul;57(1):7-15.

haematogenous osteomyelitis. Med J Malaysia. 2004 Dec;59 Suppl F:72-4. 16. Szczêsny G, Interewicz B, Swoboda-Kopeć E, Olszewski WL, G órecki A,

5. Canale ST, Puhl J, Watson FM, Gillespie R. Acute osteomyelitis following Wasilewski P. Bacteriology of callus of closed fractures of tibia and femur.

closed fractures. Report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975 Apr;57(3): J Trauma. 2008 Oct;65(4):837-42.

415-8. 17. Szczesny G, Olszewski WL, Gewartowska M, Zaleska M, Górecki A. The healing

6. Cozen L. Four unusual cases of osteomyelitis in adults. West J Surg Obstet of tibial fracture and response of the local lymphatic system. J Trauma. 2007

Gynecol. 1958 Jan-Feb;66(1):36-9. Oct;63(4):849-54.

7. Folberg C, Hardy AE, Isaacs RD, Ellis-Pegler RB. Osteomyelitis complicating a 18. Medina E, Goldmann O, Toppel AW, Chhatwal GS. Survival of Streptococcus

closed fracture. N Z Med J. 1987 Jun 24;100(826):392-3. pyogenes within host phagocytic cells: a pathogenic mechanism for persistence and

8. Hardy AE, Nicol RO. Closed fractures complicated by acute hematogenous os- systemic invasion. J Infect Dis. 2003 Feb 15;187(4):597-603. Epub 2003 Feb 7.

teomyelitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985 Dec;(201):190-5. 19. Nuwayhid ZB, Aronoff DM, Mulla ZD. Blunt trauma as a risk factor for group A

9. Stuart D. Local osteo-articular tuberculosis complicating closed fractures: report streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis. Ann Epidemiol. 2007 Nov;17(11):878-81. Epub

of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976 May;58(2):248-9. 2007 Aug 13.

10. Veranis N, Laliotis N, Vlachos E. Acute osteomyelitis complicating a closed 20. Cea-Pereiro JC, Garcia-Meijide J, Mera-Varela A, Gomez-Reino JJ. A comparison

radial fracture in a child. A case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992 Jun;63(3): between septic bursitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus and those caused by

341-2. other organisms. Clin Rheumatol. 2001;20(1):10-4.

11. Watson FM, Whitesides TE Jr. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis complicating 21. Gustilo RB, Anderson JT. Prevention of infection in the treatment of one thou-

closed fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976 Jun;(117):296-302. sand and twenty-five open fractures of long bones: retrospective and prospective

12. Weidle PA, Brankamp J, Dedy N, Haenisch C, Windolf J, Jonas M. Compli- analyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976 Jun;58(4):453-8.

cation of a closed Colles-fracture: necrotising fasciitis with lethal outcome. 22. Siebert CH, Arens S, Hansis M. The role of surgical trauma in the aetiology of

A case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009 Jan;129(1):75-8. Epub 2008 postoperative wound infection-quantification of surgery induced trauma. Hyg Med

Oct 18. 1995; 20:474-80.

Você também pode gostar

- Ce Sunt InfectiileDocumento5 páginasCe Sunt Infectiilegeorgi.annaAinda não há avaliações

- Moluskulum ContangiosumDocumento9 páginasMoluskulum ContangiosumDennisSujayaAinda não há avaliações

- Pathogenesis of InfectionDocumento8 páginasPathogenesis of InfectionCardion Rayon Bali UIN MalangAinda não há avaliações

- Fig. 1 Fig. 2: E. Linton Et AlDocumento2 páginasFig. 1 Fig. 2: E. Linton Et AlFitriAndiniAinda não há avaliações

- Cshperspectmed BAC A012393Documento14 páginasCshperspectmed BAC A012393RaffaharianggaraAinda não há avaliações

- Pathophysiology of Meningococcal Meningitis and SepticaemiaDocumento8 páginasPathophysiology of Meningococcal Meningitis and SepticaemiaEugen TarnovschiAinda não há avaliações

- 3 s2.0 B9780323188241000140 PDFDocumento7 páginas3 s2.0 B9780323188241000140 PDFKaren AfianAinda não há avaliações

- 16 - Trauma MedicineDocumento17 páginas16 - Trauma MedicinePeterAinda não há avaliações

- Ryder 2001Documento12 páginasRyder 2001Febria Valentine AritonangAinda não há avaliações

- Inflammation and wound healing overviewDocumento2 páginasInflammation and wound healing overviewJulia Rae Delos SantosAinda não há avaliações

- Ghid Oftalmologic Preview PlusDocumento6 páginasGhid Oftalmologic Preview PlusIoana ElenaAinda não há avaliações

- Gas GangreneDocumento3 páginasGas Gangrenecareyale12Ainda não há avaliações

- COVID-19 Is, in The End, An Endothelial Disease: Peter Libby and Thomas Lu ScherDocumento7 páginasCOVID-19 Is, in The End, An Endothelial Disease: Peter Libby and Thomas Lu ScherJose Antonio RamosAinda não há avaliações

- Periodic Synopsis: Bacterial Infections of The SkinDocumento7 páginasPeriodic Synopsis: Bacterial Infections of The SkinMDAinda não há avaliações

- Tissue Response To Injury: Ubiquity of Cell Injury Makes Inflammation-Mediated Disorders UbiquitousDocumento2 páginasTissue Response To Injury: Ubiquity of Cell Injury Makes Inflammation-Mediated Disorders UbiquitousDayanna TorresAinda não há avaliações

- Toxoplasma Gondii: and The Blood-Brain BarrierDocumento12 páginasToxoplasma Gondii: and The Blood-Brain BarrierValentina TjandraAinda não há avaliações

- (ANDREWS) Folliculitis, Furuncle, CarbuncleDocumento8 páginas(ANDREWS) Folliculitis, Furuncle, CarbunclempsoletaAinda não há avaliações

- INCOMPLETE Miscellaneous - ProtozoaDocumento11 páginasINCOMPLETE Miscellaneous - ProtozoaNOR-FATIMAH BARATAinda não há avaliações

- Cumitech 23 - Infections of The Skin and Subcutaneous Tissues PDFDocumento16 páginasCumitech 23 - Infections of The Skin and Subcutaneous Tissues PDFAnjali MohanAinda não há avaliações

- How Do Extracellular Pathogens Cross The Blood-Brain Barrier?Documento6 páginasHow Do Extracellular Pathogens Cross The Blood-Brain Barrier?Jade LoberianoAinda não há avaliações

- Dental Boards3Documento6 páginasDental Boards3Isabelle TanAinda não há avaliações

- MOLLUSCUMDocumento5 páginasMOLLUSCUMafeefaAinda não há avaliações

- Rare Case Report STSG Approach in Necrotizing Fasciitis Fix 1Documento7 páginasRare Case Report STSG Approach in Necrotizing Fasciitis Fix 1Wahyu Kartiko TomoAinda não há avaliações

- Mau Di TranslateDocumento4 páginasMau Di TranslateErmanW'theRachingMuhamadAinda não há avaliações

- ImunologyDocumento28 páginasImunologyLediraAinda não há avaliações

- Covid Is An Endothelial Disease 2020 SeptDocumento7 páginasCovid Is An Endothelial Disease 2020 SeptDaniela Mădălina GhețuAinda não há avaliações

- Skin MicrobiotaDocumento4 páginasSkin MicrobiotaDianaAinda não há avaliações

- Autosensitisation Autoeczematisation Reactions in A Case of Diaper Dermatitis Candidiasis NMJ-55-274Documento2 páginasAutosensitisation Autoeczematisation Reactions in A Case of Diaper Dermatitis Candidiasis NMJ-55-274cgs08Ainda não há avaliações

- A Study of Clinical Profile and Outcome of Patients Suffering From Necrotizing Soft Tissue InfectionDocumento19 páginasA Study of Clinical Profile and Outcome of Patients Suffering From Necrotizing Soft Tissue InfectionIJAR JOURNALAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnosing Foot Infection in Diabetes: SupplementarticleDocumento4 páginasDiagnosing Foot Infection in Diabetes: SupplementarticleTutorial D3Ainda não há avaliações

- Nihms371504 PDFDocumento37 páginasNihms371504 PDFYuniarAinda não há avaliações

- 1w72mlbDocumento5 páginas1w72mlbnandaaa aprilAinda não há avaliações

- Rspa 1927 0118Documento22 páginasRspa 1927 0118Debabrata NagAinda não há avaliações

- Streptococcal Skin InfectionsssDocumento6 páginasStreptococcal Skin InfectionsssteenaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 PATHO 2a - Inflammation - Dr. BailonDocumento12 páginas1 PATHO 2a - Inflammation - Dr. BailontonAinda não há avaliações

- Helmintos NematodosDocumento12 páginasHelmintos NematodosHANNIAAinda não há avaliações

- Treatment of Chronic InfectionDocumento6 páginasTreatment of Chronic InfectionJonathan Munoz EscobedoAinda não há avaliações

- Mechanism of Meningeal Invasion by Neisseria MeningitidisDocumento10 páginasMechanism of Meningeal Invasion by Neisseria MeningitidisRaffaharianggaraAinda não há avaliações

- MolluscumDocumento3 páginasMolluscumSatria Jaya PerkasaAinda não há avaliações

- In Ammation, Immunity and Allergy: Learning ObjectivesDocumento6 páginasIn Ammation, Immunity and Allergy: Learning ObjectivesJavier VeraAinda não há avaliações

- 2020 Cutaneous Protothecosis As An Unusual Complication Following Dermal Filler Injection A Case Report.Documento4 páginas2020 Cutaneous Protothecosis As An Unusual Complication Following Dermal Filler Injection A Case Report.Dimitris RodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- The Internal Treatment of Traumatic InjuryDocumento24 páginasThe Internal Treatment of Traumatic Injuryyevgenfomin7Ainda não há avaliações

- A Contribution To The Mathematical Theory o F EpidemicsDocumento22 páginasA Contribution To The Mathematical Theory o F Epidemicssamson jinaduAinda não há avaliações

- Venkatraman K PDFDocumento3 páginasVenkatraman K PDFRana Zara AthayaAinda não há avaliações

- GFCH Internal Treatment of TraumaDocumento24 páginasGFCH Internal Treatment of TraumaAndré LourivalAinda não há avaliações

- HAPP-PICO Tissue Pathology Journal ResearchDocumento4 páginasHAPP-PICO Tissue Pathology Journal ResearchArlynn MartinezAinda não há avaliações

- Chronic Peritoneal Dialysis Access Exit Site InfectionsDocumento11 páginasChronic Peritoneal Dialysis Access Exit Site InfectionsMimi MuhammidaAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomical Barriers Against SARS-CoV-2 Neuroinvasion at Vulnerable Interfaces Visualized in Deceased COVID-19 PatientsDocumento24 páginasAnatomical Barriers Against SARS-CoV-2 Neuroinvasion at Vulnerable Interfaces Visualized in Deceased COVID-19 PatientsRick ZHUAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture Notes: August 02, 2011 Topic: Surgical Infection: ST NDDocumento6 páginasLecture Notes: August 02, 2011 Topic: Surgical Infection: ST NDLiezel Dejumo BartolataAinda não há avaliações

- From Inflammation To Sickness Historical PerspectiveDocumento5 páginasFrom Inflammation To Sickness Historical PerspectiveВладимир ДружининAinda não há avaliações

- CME 301-Cutaneous MucormycosisDocumento4 páginasCME 301-Cutaneous MucormycosisTri Hasan BasriAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Bacterial Infection and PathogenesisDocumento31 páginas5 Bacterial Infection and PathogenesisjakeyAinda não há avaliações

- Rationale of Endodontic TreatmentDocumento30 páginasRationale of Endodontic Treatmentaakriti100% (1)

- Joint InfectionsDocumento10 páginasJoint InfectionsJPAinda não há avaliações

- Case Report: An Unusual Unilateral Pterygium - A Secondary Pterygium Caused by Parasitosis in The Scleral FistulaDocumento3 páginasCase Report: An Unusual Unilateral Pterygium - A Secondary Pterygium Caused by Parasitosis in The Scleral FistulaGrnitrv 22Ainda não há avaliações

- Lecture 10 Wound HealingDocumento10 páginasLecture 10 Wound HealingRose Ann RaquizaAinda não há avaliações

- Konjungtivitis GonoreDocumento2 páginasKonjungtivitis Gonorefk unswagatiAinda não há avaliações

- CUTANEOUS Tuberculosis - AjmDocumento3 páginasCUTANEOUS Tuberculosis - Ajmfredrick damianAinda não há avaliações

- Angina Ludwig 2011Documento3 páginasAngina Ludwig 2011Arini Dwi NastitiAinda não há avaliações

- Special Topics and General Characteristics: Diseases Caused by ProtistaNo EverandSpecial Topics and General Characteristics: Diseases Caused by ProtistaDavid WeinmanAinda não há avaliações

- Mastery of Surgery VolumeII 5thed 2006Documento2.626 páginasMastery of Surgery VolumeII 5thed 2006bigdocAinda não há avaliações

- Yoga SadhguruDocumento6 páginasYoga Sadhgurucosti.sorescuAinda não há avaliações

- Set1 - Final FRCA Viva Qs - June 2009 PDFDocumento25 páginasSet1 - Final FRCA Viva Qs - June 2009 PDFAdham SalemAinda não há avaliações

- SirsDocumento33 páginasSirsBinod Bade ShresthaAinda não há avaliações

- ACTION Personal Trainer Certification Textbook v2Documento334 páginasACTION Personal Trainer Certification Textbook v2dreamsheikh100% (12)

- CAPE Communication Studies 2009 P3BDocumento4 páginasCAPE Communication Studies 2009 P3BRiaz JokanAinda não há avaliações

- Metabolic Adaptation of the Human Body During StarvationDocumento8 páginasMetabolic Adaptation of the Human Body During StarvationYousef Al-AmeenAinda não há avaliações

- Adding An "R" in The "DOPE" Mnemonic For Ventilator TroubleshootingDocumento1 páginaAdding An "R" in The "DOPE" Mnemonic For Ventilator TroubleshootingkelvinaAinda não há avaliações

- Curriculum Vitae: Penata Muda Tk-1 / III BDocumento6 páginasCurriculum Vitae: Penata Muda Tk-1 / III BLuciano NawaAinda não há avaliações

- Embryology: Odontogenesis Odontogenesis - Origin and Tissue Formation of TeethDocumento2 páginasEmbryology: Odontogenesis Odontogenesis - Origin and Tissue Formation of TeethRosette GoAinda não há avaliações

- Physio Gastrointestinal Motility PDFDocumento11 páginasPhysio Gastrointestinal Motility PDFKim RamosAinda não há avaliações

- Photosynthesis and RespirationDocumento46 páginasPhotosynthesis and RespirationCarmsAinda não há avaliações

- Neurotransmitters and Intellectual Function AssessmentDocumento3 páginasNeurotransmitters and Intellectual Function AssessmentMarissa AsimAinda não há avaliações

- Chemistry and Fundamental BiotechnologyDocumento3 páginasChemistry and Fundamental BiotechnologyRaweeha SaifAinda não há avaliações

- Cell Death Via ApoptosisDocumento17 páginasCell Death Via ApoptosisFilip MilošićAinda não há avaliações

- Muscle and Nerve McqsDocumento6 páginasMuscle and Nerve McqsShan ShaniAinda não há avaliações

- NPO GuidelinesDocumento2 páginasNPO GuidelinesDan HoAinda não há avaliações

- Free Online Mock Test For MHT-CET BIOLOGY PDFDocumento28 páginasFree Online Mock Test For MHT-CET BIOLOGY PDFBiologyForMHTCET75% (8)

- (VCE Biology) 2005 Chemology Unit 2 Exam and Solutions PDFDocumento22 páginas(VCE Biology) 2005 Chemology Unit 2 Exam and Solutions PDFJustine LyAinda não há avaliações

- ATPL 040.human Factor NotesDocumento22 páginasATPL 040.human Factor NotesAbu BrahimAinda não há avaliações

- 87Documento130 páginas87Sasa Svikovic100% (2)

- Inflammation and Mental HealthDocumento41 páginasInflammation and Mental HealthanindyaguptaAinda não há avaliações

- GR 173259Documento11 páginasGR 173259Anonymous wDganZAinda não há avaliações

- Life ProcessesDocumento52 páginasLife ProcessesSimran Josan100% (2)

- IPPA Procedures Guide for Nursing StudentsDocumento5 páginasIPPA Procedures Guide for Nursing StudentsJulieeAinda não há avaliações

- 0038 Foldrajz Palaeontologyda PDFDocumento54 páginas0038 Foldrajz Palaeontologyda PDFRamón F. Zapata Sánchez100% (1)

- How To Analyze EkgsDocumento40 páginasHow To Analyze EkgsJosh WeisAinda não há avaliações

- Therapeutic Exedrcises & TechniquesDocumento4 páginasTherapeutic Exedrcises & Techniquesrabia khalidAinda não há avaliações

- BehaviorismDocumento22 páginasBehaviorismOlcay Sanem SipahioğluAinda não há avaliações

- 11.1 Antibody Production and VaccinationDocumento28 páginas11.1 Antibody Production and VaccinationFRENCHONLYAinda não há avaliações