Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Sarmila Bose, Dead Reckoning: Memories of The 1971 Bangladesh War Tawfique Al-Mubarak, IAIS Malaysia

Enviado por

TariqMahmood0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

55 visualizações3 páginasArticle 352

Título original

03

Direitos autorais

© © All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoArticle 352

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

55 visualizações3 páginasSarmila Bose, Dead Reckoning: Memories of The 1971 Bangladesh War Tawfique Al-Mubarak, IAIS Malaysia

Enviado por

TariqMahmoodArticle 352

Direitos autorais:

© All Rights Reserved

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 3

BOOK REVIEWS 472

Sarmila Bose, Dead Reckoning: Memories of the 1971 Bangladesh War

(NY: Columbia University Press, 2011), x + 239 pp., ISBN 978-0-231-70164-8, $33.75.

Tawfique al-Mubarak, IAIS Malaysia

In 1971, by a devastating war, Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) achieved

independence from (West) Pakistan. Since then, both parties have documented

and presented their research findings on the war. However, many of these findings

have lacked credibility. Perhaps the only objective account on the 1971 war has

been Richard Sisson and Leo Rose’s War and Secession: Pakistan, India and the

Creation of Bangladesh (1991). Sarmila Bose’s recent work, Dead Reckoning,

today constitutes a significant contribution to the research on Bangladesh’s war

of independence, all the more so for its unique methodology in using multiple

sources of original information and cross-checked eyewitness testimonies

from all parties involved. Pakistani army personnel as well as Bangladeshi

muktijoddhas (freedom fighters) and victims of the war were interviewed to

authenticate currently available materials, many of which appear to have been

exaggerated with the force of emotion. This distinguishes the work from many

other books authored by proponents of either party to the conflict. This book is

certainly an eye-opener for researchers on the 1971 war.

The book is divided into nine chapters, each referring to the approximate

chronology of events from December 1970 until the end of the war in December

1971. Chapter one (“Call to Arms”) describes the general election of 1970 and

the victory of the Awami League (AL) led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman with a

majority of seats in the parliament. Bhutto, despite losing the election, aspired to

be Prime Minister of all Pakistan, and hence refused to accept the negotiations

mediated by Yahya Khan, who was then the President and Chief Martial Law

Administrator of Pakistan. Sheikh Mujib, too, was adamant that he should

become Prime Minister. The negotiations ended without fruitful results; thus

Yahya announced the postponement of the national assembly. This immediately

set off violent revolts by the Bengalis. Sheikh Mujib’s speech on 7 March stopped

just short of declaring independence; he was still negotiating with the expectation

of becoming the Prime Minister.

The Bengalis’ revolts spread throughout the state immediately after the

announcement. The following chapter (“Military Inaction”) describes how the

control over East Pakistan weakened and shifted to a parallel government led by

Sheikh Mujib, with no mutually agreed resolution to the conflict. In the Joydevpur

incident of 19 March 1971, two Bengali citizens were killed in a shootout between

civilians and the Pakistan army, exacerbating the tense situation between the two

parts of Pakistan.

ICR 4.3 Produced and distributed by IAIS Malaysia

473 SARMILA BOSE

Chapter three (“Military Action”) describes “Operation Searchlight” conducted

on the Dhaka University campus by the Pakistani government on the night of 25

March 1971, “a military solution, which ultimately proved to be catastrophic

for Pakistan.” The Pakistani army crushed the resistance of the students in the

residential halls, and elsewhere in adjoining apartments of the faculty, innocent

unarmed civilians were massacred.

Chapters 4-8 detail the brutal atrocities committed by both of the warring sides.

“Uncivil War”, the fourth chapter, illustrates through ten cases the bitter feud that

festered during subsequent months, following the military action of 25 March. As

the Pakistani army had killed innocent civilians and Bengali Hindus, the Bengalis

also killed their Bihari brethren in East Pakistan. In Joydevpur and Gazipur, Bengali

soldiers revolted against the non-Bengali and West Pakistani army personnel,

killing West Pakistani officers and their families. In Khulna, at the People’s Jute

Mill, the Bengalis took up whatever weapons they found and attacked the Biharis,

“killing everyone they could find – men, women and children.” Similar incidents

took place at Mymengsingh, Santahar and at Chittagong’s Karnaphuli Mill. The

Pakistan government’s White Paper on the gruesome situation estimates that

about 15,000 Biharis were killed. Chaos and bloodshed spread widely throughout

the state during the earlier months after the military action.

Chapter 5 (“Village of Widows”) describes the mass killing at Thanapara

village in Rajshahi by the Pakistani army on 13 April 1971. Men were separated

from women and children and brutally shot, their bodies stacked in a pile and set

on fire. Bose writes with emotion that this was “one of the grisliest of stories I

heard in the course of my study of the 1971 war!”

The chapter “Hounding of Hindus” describes how Hindus were murdered by

the Pakistani army at Chuknagar, at the borders of Khulna and Jessore districts,

while they were fleeing their homes because of looting and harassment, mostly

by local Bengali Muslims. Questioning the popular Bengali narration that 10,000

people were murdered there, Bose considers it a figure “too large” that an army

contingent of just three truck loads of soldiers could murderously dispatch within

just a couple of hours that many people. The scepticism that Bose, a Hindu, here

evinces suggests a concern for strict objectivity of analysis in her research into

what was certainly a heinous crime.

The seventh chapter (“Hit and Run”) provides documentation of instances

in which underground Bengali guerrillas like Alvi and Rumi, having trained in

India, demonstrated their dedication to an independent Bangladesh. The bestial

killings of prominent Bengali scholars by the Al-Badr and Al-Shams groups at

the Rayerbazar brick-kiln and other places are described in the eighth chapter

(“Fratricide”). The muktijoddhas too, it must be said, similarly killed Bengali

supporters of a united Pakistan in the most brutal manner. Bengalis killing other

ISLAM AND CIVILISATIONAL RENEWAL

BOOK REVIEWS 474

Bengalis for either supporting or opposing a united Pakistan became a regular

occurrence during the last weeks of December 1971.

The last chapter (“Words and Numbers”) addresses the myth underlying ‘Sheikh

Mujib’s famous statement: “I discovered that they had killed three million of my

people.” Bose argues that so far no authentic references have substantiated the

claim. She concludes that between 50,000 to 100,000 people perished in the war

of 1971, including combatants and non-combatants, on both sides. Similarly, the

often-cited figure of 93,000 Pakistani soldiers taken as POWs is also unrealistic,

given a contingent which had a total of only 55,000 members in East Pakistan

during the war, civilian officials and army personnel combined.

The fundamental contribution of the book is that it reveals how the whole

discourse of liberation and separation has been sullied by fictions. Although the

popular Bengali versions of the 1971 war describe the atrocities committed by

the Pakistani army, rarely is mention made of Bengali attacks on Biharis and

non-Bengalis.

Bose does not directly address the current situation in which political leaders

are undergoing trials at the International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) in Bangladesh,

but her descriptions suggest that these trials are largely driven by concocted

discourses for political motives. The book is significant for employing a robust

methodology to uncover the myths and realities surrounding the 1971 war, which

Bose concludes left “a land of violence with a legacy of intolerance of difference

and a tendency to respond to political opposition with intimidation, brutalization

and extermination” for the next generation.

ICR 4.3 Produced and distributed by IAIS Malaysia

Você também pode gostar

- Anatomy of Violence - Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan N 1971Documento16 páginasAnatomy of Violence - Analysis of Civil War in East Pakistan N 1971Rage EzekielAinda não há avaliações

- A Critique of Sarmila Bose's Book Absolving Pakistan of Its War Crimes in The 1971 Genocide in BangladeshDocumento13 páginasA Critique of Sarmila Bose's Book Absolving Pakistan of Its War Crimes in The 1971 Genocide in BangladeshTarek FatahAinda não há avaliações

- The Great TragedyDocumento79 páginasThe Great TragedySani Panhwar100% (2)

- A Critical Evaluation of Icj Report On Bangladesh GenocideDocumento23 páginasA Critical Evaluation of Icj Report On Bangladesh GenocideAwami Brutality67% (3)

- UntitledDocumento37 páginasUntitledapi-224886503Ainda não há avaliações

- Uganda Railway From Communications in AfricaDocumento28 páginasUganda Railway From Communications in AfricaPickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- 12 Baluch in 1971 WarDocumento9 páginas12 Baluch in 1971 WarStrategicus Publications100% (1)

- Pak Bibliography PDFDocumento587 páginasPak Bibliography PDFZia Ur RehmanAinda não há avaliações

- The Nature of Insurgency in AfghanistanDocumento135 páginasThe Nature of Insurgency in Afghanistanzahid maanAinda não há avaliações

- Nur KhanDocumento11 páginasNur KhanTalha Waqas100% (1)

- 11 Baluch The Battalion Which Captured PanduDocumento39 páginas11 Baluch The Battalion Which Captured PanduStrategicus PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar Report 1971 War CLAWSDocumento15 páginasSeminar Report 1971 War CLAWSMalem NingthoujaAinda não há avaliações

- Nishan e HaiderDocumento14 páginasNishan e Haiderapi-27197991Ainda não há avaliações

- Major General Zia Ul Haq Nur, Punjab Regiment-ObituaryDocumento31 páginasMajor General Zia Ul Haq Nur, Punjab Regiment-ObituaryStrategicus PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper On Shah Ahmad NoraniDocumento253 páginasResearch Paper On Shah Ahmad NoraniAli RazaAinda não há avaliações

- The military and politics in Pakistan: A history of tensions and transitionsDocumento22 páginasThe military and politics in Pakistan: A history of tensions and transitionsahmedAinda não há avaliações

- 282 799 1 PBDocumento6 páginas282 799 1 PBAshok KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Book - Indo-Pak War - 1971Documento386 páginasBook - Indo-Pak War - 1971amitbhaiAinda não há avaliações

- Ed Mohit Roy Deshkal Nov2010 TranslationDocumento14 páginasEd Mohit Roy Deshkal Nov2010 Translationrathodharsh008Ainda não há avaliações

- Book ReviewDocumento4 páginasBook ReviewBismah Uzair100% (1)

- FinalDocumento22 páginasFinalRamakant YadavAinda não há avaliações

- The East Pakistan Tragedy by Tom StaceyDocumento148 páginasThe East Pakistan Tragedy by Tom StaceyAli Khan0% (1)

- Pakistan SindhregimentDocumento4 páginasPakistan SindhregimentSanjay BabuAinda não há avaliações

- Major A. M. Sloan Martyr in Kashmir 1948 WarDocumento4 páginasMajor A. M. Sloan Martyr in Kashmir 1948 WarAhmad Ali MalikAinda não há avaliações

- Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 - Wikipedia PDFDocumento197 páginasIndo-Pakistani War of 1965 - Wikipedia PDFAbdul QudoosAinda não há avaliações

- Report of Fall of DhakaDocumento14 páginasReport of Fall of DhakaNight BravoAinda não há avaliações

- Pavo 11 Cavalry-History and Battle HonoursDocumento69 páginasPavo 11 Cavalry-History and Battle HonoursStrategicus PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Express India China FINALDocumento46 páginasExpress India China FINALShyam RatanAinda não há avaliações

- IWM Book 11-06-2014Documento242 páginasIWM Book 11-06-2014pl-junkAinda não há avaliações

- An Analysis of Kargil: "The Purpose of Deterrence Is To Deter"Documento10 páginasAn Analysis of Kargil: "The Purpose of Deterrence Is To Deter"ikonoclast13456Ainda não há avaliações

- Pakistan Army in KashmirDocumento80 páginasPakistan Army in KashmirStrategicus PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Illegal Immigration From BangladeshDocumento120 páginasIllegal Immigration From BangladeshKarthik VMSAinda não há avaliações

- State Versus Nations in Pakistan by Ashok BehuriaDocumento129 páginasState Versus Nations in Pakistan by Ashok Behuriasanghamitrab100% (1)

- Race and Recrutiment in British India ArmyDocumento39 páginasRace and Recrutiment in British India Armyzeba abbasAinda não há avaliações

- Pak USSR RelationDocumento31 páginasPak USSR RelationMusharafmushammad100% (1)

- 3 War of Independence 1857Documento3 páginas3 War of Independence 1857Salman JoharAinda não há avaliações

- Behind The Scenes Major General JoginderDocumento43 páginasBehind The Scenes Major General JoginderMahmud AnsariAinda não há avaliações

- Battle of JamalpurDocumento24 páginasBattle of Jamalpurjuliusbd46100% (2)

- In The Name of Allah, The Beneficient and The MercifulDocumento39 páginasIn The Name of Allah, The Beneficient and The Mercifulumer shafiqueAinda não há avaliações

- Sri Lankan Civil WarDocumento13 páginasSri Lankan Civil WarJack PraveenAinda não há avaliações

- Bangladesh Liberation PDFDocumento3 páginasBangladesh Liberation PDFSanjay Babu100% (1)

- TimeLine of Pak AffairsDocumento2 páginasTimeLine of Pak Affairsﹺ ﹺ ﹺ ﹺAinda não há avaliações

- Flight of The Falcon - Demolishing Myths of Indo Pak Wars 1965-1971 - Sajad S. Haider PDFDocumento185 páginasFlight of The Falcon - Demolishing Myths of Indo Pak Wars 1965-1971 - Sajad S. Haider PDFOsman MustafaAinda não há avaliações

- In Search of Solutions - The Autobiography of Mir Ghaus Buksh Bizenjo PDFDocumento137 páginasIn Search of Solutions - The Autobiography of Mir Ghaus Buksh Bizenjo PDFamnllhgllAinda não há avaliações

- Book Review - The Monsoon War Young Officers Reminisce - 1965 India Pak WarDocumento11 páginasBook Review - The Monsoon War Young Officers Reminisce - 1965 India Pak War17czwAinda não há avaliações

- Afghan Report#5Documento83 páginasAfghan Report#5Noel Jameel Abdullah100% (1)

- Cordesman Pakistan WebDocumento218 páginasCordesman Pakistan WebnasserAinda não há avaliações

- The Rise of The Liberation Tigers: Conventional Operations in The Sri Lankan Civil War, 1990-2001Documento86 páginasThe Rise of The Liberation Tigers: Conventional Operations in The Sri Lankan Civil War, 1990-2001Ray ZxAinda não há avaliações

- Nagorno-Karabakh War - Timeline and GraphicsDocumento8 páginasNagorno-Karabakh War - Timeline and GraphicsSérgio SantanaAinda não há avaliações

- Afghan Guns Captured at Battle of Kandahar by PAVO 11 CavalryDocumento20 páginasAfghan Guns Captured at Battle of Kandahar by PAVO 11 CavalryStrategicus PublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Why India Lost The Sino Indian War of 1961Documento69 páginasWhy India Lost The Sino Indian War of 1961ram9261891Ainda não há avaliações

- Moonlight Marauders: Iaf Fighter Squadron Strikes by Night Indo-Pak War, Dec 1971No EverandMoonlight Marauders: Iaf Fighter Squadron Strikes by Night Indo-Pak War, Dec 1971Ainda não há avaliações

- The Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921No EverandThe Irish War of Independence: The Definitive Account of the Anglo Irish War of 1919 - 1921Nota: 3 de 5 estrelas3/5 (2)

- War, Coups and Terror: Pakistan's Army in Years of TurmoilNo EverandWar, Coups and Terror: Pakistan's Army in Years of TurmoilNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- India Marching: Reflections from a Nationalistic PerspectiveNo EverandIndia Marching: Reflections from a Nationalistic PerspectiveAinda não há avaliações

- Trials of 1971 Bangladesh Genocide: Through a Legal LensNo EverandTrials of 1971 Bangladesh Genocide: Through a Legal LensAinda não há avaliações

- Korean War—Chinese Invasion: People's Liberation Army Crosses the Yalu, October 1950–March 1951No EverandKorean War—Chinese Invasion: People's Liberation Army Crosses the Yalu, October 1950–March 1951Ainda não há avaliações

- Week 02 - Geology Earth's Interior & Branches of GeologyDocumento28 páginasWeek 02 - Geology Earth's Interior & Branches of GeologyTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Week 01 - Introduction & Importance of Geology in Civil EngineeringDocumento26 páginasWeek 01 - Introduction & Importance of Geology in Civil EngineeringTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Ashfaq C.VDocumento4 páginasAshfaq C.VTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Materials Specifications for PEB Structure ProjectDocumento1 páginaMaterials Specifications for PEB Structure ProjectTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

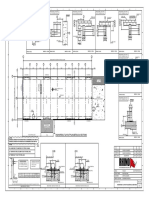

- SPLICE BOLT AND MEMBER TABLE DETAILSDocumento1 páginaSPLICE BOLT AND MEMBER TABLE DETAILSTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- PRTCL PrintDupBill1Documento1 páginaPRTCL PrintDupBill1TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Axpert VM IV - Ficha TécnicaDocumento1 páginaAxpert VM IV - Ficha TécnicaTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 2 2Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 2 2TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Special Stipulations NUTECH UniversityDocumento2 páginasSpecial Stipulations NUTECH UniversityTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Detailed Price ComparisonDocumento1 páginaDetailed Price ComparisonTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 1 1Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 1 1TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 4 4Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 4 4TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 12 12Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 12 12TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 8 8Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 8 8TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 5 5Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 5 5TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- ID WBS Task Mode Task Name Duration Start 1 2 3Documento8 páginasID WBS Task Mode Task Name Duration Start 1 2 3TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Member table and wall sheeting specsDocumento1 páginaMember table and wall sheeting specsTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 9 9Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 9 9TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Sulemani JahanianDocumento11 páginasSulemani JahanianTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 11 11Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 11 11TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 13 13Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 13 13TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 10 10Documento1 páginaRB A225 Approval Rev 1 - 10 10TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- RB A225 APPROVAL REV 1 - 14 EndDocumento1 páginaRB A225 APPROVAL REV 1 - 14 EndTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Kamram Project Nov 2017Documento2 páginasKamram Project Nov 2017TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Ashiq Sahib F F Model PDFDocumento1 páginaAshiq Sahib F F Model PDFTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Mind.: Lachesis Mutus Bushmaster or Surucucu (Lachesis)Documento2 páginasMind.: Lachesis Mutus Bushmaster or Surucucu (Lachesis)TariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Ashiq Sahib F F Model PDFDocumento1 páginaAshiq Sahib F F Model PDFTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Before The Registerar Cooperatives Punjab LahoreDocumento3 páginasBefore The Registerar Cooperatives Punjab LahoreTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Mall of Sargodha: RCC Pipe Design For Disposal From Site 3 To OutletDocumento5 páginasMall of Sargodha: RCC Pipe Design For Disposal From Site 3 To OutletTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Petition Seeks Protection of Leased LandDocumento8 páginasPetition Seeks Protection of Leased LandTariqMahmoodAinda não há avaliações

- Ulep vs. Legal Aid, Inc. Cease and Desist Order on Unethical AdvertisementsDocumento3 páginasUlep vs. Legal Aid, Inc. Cease and Desist Order on Unethical AdvertisementsRalph Jarvis Hermosilla AlindoganAinda não há avaliações

- How To Draft A MemorialDocumento21 páginasHow To Draft A MemorialSahil SalaarAinda não há avaliações

- KK SummaryDocumento3 páginasKK SummaryDa BadestAinda não há avaliações

- Module in Public Policy and Program AdministrationDocumento73 páginasModule in Public Policy and Program AdministrationRommel Rios Regala100% (20)

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 541, Docket 94-1219Documento8 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 541, Docket 94-1219Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- Samson v. AguirreDocumento2 páginasSamson v. AguirreNoreenesse SantosAinda não há avaliações

- Official Funeral - of Minister Jackson Mphikwa MthembuDocumento8 páginasOfficial Funeral - of Minister Jackson Mphikwa MthembueNCA.comAinda não há avaliações

- Awards ThisDocumento4 páginasAwards ThisRyan Carl IbarraAinda não há avaliações

- Osmeña vs. Pendatun (Digest)Documento1 páginaOsmeña vs. Pendatun (Digest)Precious100% (2)

- Cordora vs. ComelecDocumento2 páginasCordora vs. ComelecVanna Vefsie DiscayaAinda não há avaliações

- Addressing Adversities Through Gulayan sa Paaralan ProgramDocumento3 páginasAddressing Adversities Through Gulayan sa Paaralan ProgramCristoper BodionganAinda não há avaliações

- Mrs Mardini refugee status assessmentDocumento9 páginasMrs Mardini refugee status assessmentJeff SeaboardsAinda não há avaliações

- GROUP 2 - The Filipino Is Worth Dying ForDocumento2 páginasGROUP 2 - The Filipino Is Worth Dying ForGian DelcanoAinda não há avaliações

- Anne FrankDocumento13 páginasAnne FrankMaria IatanAinda não há avaliações

- Command Economy Systems and Growth ModelsDocumento118 páginasCommand Economy Systems and Growth Modelsmeenaroja100% (1)

- Central and Southwest Asia WebQuestDocumento4 páginasCentral and Southwest Asia WebQuestapi-17589331Ainda não há avaliações

- Pde 5201 AssignmentDocumento18 páginasPde 5201 Assignmentolayemi morakinyoAinda não há avaliações

- Metropolitan Bank and Trust Company, Inc v. NWPCDocumento2 páginasMetropolitan Bank and Trust Company, Inc v. NWPCCedricAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Political SociologyDocumento22 páginasIntroduction To Political SociologyNeisha Kavita Mahase100% (1)

- Schindler's List Viewing GuideDocumento5 páginasSchindler's List Viewing GuideFranklin CastilloAinda não há avaliações

- A2, Lesson 1-Meet A Famous PersonDocumento4 páginasA2, Lesson 1-Meet A Famous PersonAishes ChayilAinda não há avaliações

- CRP Roles of The PreisdentDocumento8 páginasCRP Roles of The PreisdentGladys DacutanAinda não há avaliações

- Debates On End of Ideology & End of History PDFDocumento12 páginasDebates On End of Ideology & End of History PDFAadyasha MohantyAinda não há avaliações

- Kantian and Utilitarian Theories Term PaperDocumento11 páginasKantian and Utilitarian Theories Term PaperabfilsonAinda não há avaliações

- Postal Id Application FormDocumento2 páginasPostal Id Application FormDewm Dewm100% (2)

- Final Assignment 5Documento2 páginasFinal Assignment 5Anonymous ZJ4pqa50% (4)

- War ListDocumento57 páginasWar ListRaymond LullyAinda não há avaliações

- Post-Competency Checklist (Formative Assessment) : Name: Romy R. Castañeda Bsed 2D MathDocumento4 páginasPost-Competency Checklist (Formative Assessment) : Name: Romy R. Castañeda Bsed 2D MathRomy R. Castañeda50% (2)

- Abdalla Amr (2009) Understanding C.R. SIPABIODocumento10 páginasAbdalla Amr (2009) Understanding C.R. SIPABIOMary KishimbaAinda não há avaliações

- University of Cambridge International Examinations International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocumento20 páginasUniversity of Cambridge International Examinations International General Certificate of Secondary EducationMNyasuluAinda não há avaliações