Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: An Illustrative Case Example

Enviado por

Anonymous fPQaCe8Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: An Illustrative Case Example

Enviado por

Anonymous fPQaCe8Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

CLINICAL CASE REPORT

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder:

An Illustrative Case Example

ABSTRACT pated that the inclusion of specific crite-

Rachel Bryant-Waugh, BSc, MSc, Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder ria for ARFID as a category within Feed-

DPhil* (ARFID) is a new diagnostic category in ing and Eating Disorders in DSM-5 will

DSM-5. Although replacing Feeding Disor- stimulate research into its typology, prev-

der of Infancy or Early Childhood, it is alence, and incidence in different popu-

not restricted to childhood presentations. lations and facilitate the development of

In keeping with the broader aim of revi- effective, evidence-based interventions

sing and updating criteria and text to for this patient group. V C 2013 by Wiley

better reflect lifespan issues and clinical Periodicals, Inc.

expression across the age range, ARFID is

a diagnosis relevant to children, adoles- Keywords: ARFID; eating disorder;

cents, and adults. This case example of a feeding disorder; avoidant restrictive

13-year old boy with ARFID illustrates key food intake disorder; diagnosis; case

issues in diagnosis and treatment plan- example; DSM-5

ning. The issues discussed are not ex-

haustive, but serve as a guide for central (Int J Eat Disord 2013; 46:420–423)

diagnostic and treatment issues to be

considered by the clinician. It is antici-

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is bances seen in clinical practice in three main

a new diagnostic category in DSM-5,1 also likely to respects. Firstly, the residual category eating disor-

be included in ICD-11.2 A number of factors form der not otherwise specified (EDNOS) is a place-

the impetus behind its inclusion and inform the holder for a heterogeneous patient population

development of criteria for diagnosis. An overarch- forming the majority of treatment seeking individu-

ing theme for DSM-5 has been the adoption of a als.5 Secondly, Feeding Disorder of Infancy or Early

lifespan approach, the intention being to ensure Childhood has been criticized for being too broad

that due consideration is given to how symptoms and non-specific, and therefore of limited clinical

of mental disorder vary according to age and stage utility.6 Thirdly, a number of presentations which

of development.3 The aim of improving clinical do not fit any of the existing categories have been

utility across the lifespan is also a key feature of the described in middle childhood (e.g., ‘‘food avoid-

ICD-10 revision process.2 This principle has been ance emotional disorder," ‘‘selective eating").4

particularly relevant to the revision of criteria for Together, these factors have contributed to the

feeding and eating disorders as it has been recog- change to a combined section of ‘‘Feeding and Eat-

nized that some types of feeding disturbance seen ing Disorders" in DSM-5, with ARFID as a new cat-

in young children persist into later childhood, ado- egory within this section. ARFID replaces and

lescence, and even adulthood, or bear a strong sim- extends Feeding Disorder of Infancy or Early Child-

ilarity to eating disturbances that might have a later hood, with the aim of improving clinical utility by

onset.4 It is also well known that the existing DSM- adding more detail about the nature of the eating

IV-TR feeding and eating disorder categories do not disturbance as well as widening the criteria to be

adequately capture the full range of eating distur- appropriate across the age range. All clinicians will

therefore need to ensure they are fully informed

and up to date with these changes given the life-

Accepted 3 December 2012

*Correspondence to: Rachel Bryant-Waugh, BSc, MSc, DPhil,

span approach adopted in both the DSM and ICD

Consultant Clinical Psychologist and Honorary Senior Lecturer, revision process. This article provides a case

Department of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Great example of ARFID to give a clinical illustration and

Ormond Street Hospital, London, United Kingdom WC1N 3J, UK.

E-mail: rachel.bryant-waugh@gosh.nhs.uk

preliminary general guidance for assessment and

Published online in Wiley Online Library treatment planning.

(wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/eat.22093

C 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

V

420 International Journal of Eating Disorders 46:5 420–423 2013

ARFID CASE EXAMPLE

Case illustration: Presentation he would prefer to be taller and to fill out a bit. He

reported sometimes feeling hungry, but equally could

B, aged 13 years 4 months, was brought for assess- forget about eating when busy, especially when play-

ment by his mother. Ms. T. expressed her concern ing on his computer. He described recent dizzy spells

that B did not have a healthy diet and did not seem on standing from sitting or lying which had worried

to have grown much recently. She described him as him. B also described some teasing from peers about

a ‘‘lazy eater.’’ B and Ms. T. gave an account of a typ- his eating which had made him angry as ‘‘it was none

ical day’s intake consisting of a limited range of of their business.’’ B described his mood generally as

snack type foods, with little variation from one day ‘‘OK’’ and said he got on fine at school as long as peo-

to the next. B had breakfast before school but then ple did not annoy him. He had received some anger

tended to graze rather than sit down for meals. His management counseling at school, having been in a

staple daily intake included dry breakfast cereal, few fights. Academically he was functioning at a low

breadsticks, a large amount of potato chips, and bis- average level. He reported having a couple of friends

cuits. B also had one small raspberry flavored probi- who he saw in school but not outside. B agreed that

otic drink each day at his mother’s insistence, and his eating was different to his peers and described

occasionally soft ice cream from MacDonald’s or something stopping him from trying unfamiliar

some chocolate. He mostly drank cola, lemonade, or foods. He said he did not like the feeling of making

blackcurrant cordial, refusing sugar free varieties himself try things so generally didn’t.

saying they tasted horrible. He also refused all fruit,

vegetables, meat, and fish. When younger his

mother had been able to get him to take a multi-

vitamin and mineral supplement but he no longer

took this. Ms. T. described B as always having been a

fussy eater and never having been very interested in Discussion of ARFID Presentation and

food. He had slowly dropped foods from his range. Guidance for Diagnosis

At assessment, B looked pale and tired but other- In order to diagnose ARFID, the clinician needs to

wise well. He had no significant medical history, gather specific information. Table 1 includes exam-

other than a proneness to coughs and colds. He ple questions using B’s case as illustration. A num-

was 35.7 kg and 147 cm, placing him on the 9th ber of additional questions should be asked in rela-

weight centile, 10th height centile, and the 17th tion to exclusion criteria, to include establishing

BMI centile (BMI of 16.5; 90% median BMI). Ms. T. whether the avoidance or restriction might be better

had not kept good records of his weight and growth accounted for by a lack of available food or by a

but thought that he was average height as a toddler, socially sanctioned practice, in which case an ARFID

but was now one of the smaller boys in his class. diagnosis is not appropriate. Ms. T. had become

He had always been quite slight. She wondered if used to B’s restricted eating and as she had limited

he might be a late developer. Ms. T. reported that income, she had stopped spending money on food

she was 165 cm (50 5@ or 65 inches) and that B’s fa-

she knew he would not eat. She had also stopped

ther, Mr. S. was 188 cm (60 2@ or 74 inches).

offering him alternatives. However, there was other

B’s parents separated when he was 5 years old. food available in the house, and B had access to a

His father moved out of the family home and lived wider range of food at school. The avoidance or

close by with his own parents. B saw his father fre-

restriction of food intake in ARFID is not accompa-

quently but always slept at home. His eating was

nied by a disturbance in the experience of weight or

no different when with his father or his mother. Ms.

shape, which can be an important point of distinc-

T. reported that she had been the one who had of-

ten tried to encourage B to try different foods but tion from presentations of anorexia nervosa or buli-

he almost always refused. She felt that Mr. S. could mia nervosa, and should also be checked. B was re-

do more. This was becoming an increasing source alistic in his appraisal of his own body size and

of friction and Ms. T. described having given up a shape, and did not like being relatively small and

bit now that B was a teenager. B agreed his father slight. There was no other medical condition or

did not seem as concerned. B had one older and mental disorder that could account for B’s presenta-

one younger sister, neither of whom had any prob- tion. B therefore meets diagnostic criteria for ARFID;

lems of note, and neither parent had any current general requirements for Criterion A are met and

physical problems or current or past history of none of the exclusion criteria apply.

diagnosed mental disorder. At present there is insufficient evidence to sup-

When seen individually, B initially stated that he port the identification of discrete subtypes within

did not consider his eating to be a problem but said ARFID; however, in DSM-5 examples are given of

International Journal of Eating Disorders 46:5 420–423 2013 421

BRYANT-WAUGH

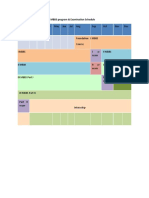

TABLE 1. Diagnostic checklist for Criterion A of ARFID with case example

Question Purpose Case of B

1. What is current food intake (range)? To establish whether intake fails to meet the Met: B’s diet is missing major food groups and is

individual’s nutritional needs particularly low in calcium, iron, and vitamins. It is

high in saturated fat, sugar, and salt. His

nutritional needs as an adolescent boy going

through puberty are not being met.

2. What is current food intake (amount)? To establish whether intake fails to meet the Unsure: B does not eat meals, but grazes

individual’s energy needs inconsistently and experiences lethargy and

episodes of dizziness. This might in part be due to

insufficient calorie intake at certain times of the

day but high intake of sugary drinks and low iron

intake might also contribute.

3. How long has the avoidance of certain To establish whether there is a persistent Met: B has been a fussy eater since early childhood,

foods or the restriction in intake been failure to meet the individual’s nutritional/ with a worsening picture.

occurring? energy needs

4. What is current weight and height and has To clarify BMI or BMI centile status and to Met: B’s BMI centile is at the lower end of the normal

there been a drop in weight and growth establish whether there is weight loss, range, however he has growth faltering with

centiles? (A1) failure to gain as expected for age, faltering growth centile having dropped significantly since

growth, etc. early childhood; height not in line with mid-

parental estimation.

5. Are there signs and symptoms of To establish whether there is clinical or lab Met: Tiredness associated with low iron intake and

nutritional deficiency or malnutrition? (A2) evidence of nutritional deficiency resulting anemia; low bone mineral density for

age on DXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry)

scan

6. Is intake supplemented in any way to To establish whether there is a dependency on Not met: B does not take any nutritional

ensure adequate intake? (A3) nutritional supplements or tube feeding supplements and is not enterally fed

7. Is there any distress or interference with To establish whether there is interference to Met: B is getting teased about his eating at school

day to day functioning related to the the individual’s social and emotional which angers him and leads to aggressive outbursts,

current eating pattern? (A4) functioning related to the eating also affecting peer relationships. It is possible that

disturbance. his academic functioning is also being impaired due

to significant nutritional compromise.

different types of avoidance or restriction of eating. to widen his diet per se, he was able to recognize

These include restriction related to an apparent that it was causing difficulty for him at school as his

lack of interest in eating or food; sensory based peers noticed and made fun of him. He was keen to

avoidance of food (e.g., the individual rejects food develop physically as he did not like being small and

on the basis of smell, color, texture, etc.), and skinny. He also appeared to be worried about his

avoidance related to feared consequences of eating, spells of light-headedness, and clearly found this an

often based on an aversive experience. Clinical ex- aversive experience. He was able to engage in think-

perience suggests that these features are not neces- ing about his eating and its consequences and will-

sarily mutually exclusive. B described forgetting to ing to see if some sessions might have benefit.

eat if he was otherwise occupied, and Ms. T. Treatment proceeded with a risk assessment and

described him as a ‘‘lazy eater’’ with a longstanding joint setting of goals, including information and edu-

lack of interest in food. However, he was also highly cation about a healthy diet, pubertal development,

selective on the basis of the color and taste of food, and consequences of nutritional compromise. A

only eating a narrow range of foods all of a cream/ broad cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approach

beige/brown color. He refused very similar alterna- was used combined with some parental involvement.

tives of his preferred foods on the basis of appear- Core strategies including self-monitoring, behavioral

ance or taste if he got as far as trying them. In treat- experiments, cognitive restructuring, and anxiety

ment his anxiety and fear of trying unfamiliar foods

management techniques were employed to address

became more apparent; although at assessment he

three overarching goals: to address nutritional risk; to

had indicated that he avoided challenging himself

work on introducing one or two foods useful for

by saying he did not like the feeling of ‘‘making

social situations with peers; to increase B’s exercise of

myself do something.’’

personal responsibility for his own health and well-

being. These broad goals were broken down into

smaller clearly defined targets.

Case illustration: Management It became clear that anxiety and low self-esteem

were major maintaining factors in B’s presentation.

B demonstrated some motivation to address his eat- Family factors also played a role and were

ing. Although he did not have any particular desire addressed as needed to facilitate progress in rela-

422 International Journal of Eating Disorders 46:5 420–423 2013

ARFID CASE EXAMPLE

tion to treatment goals. By discharge, B’s diet was Conclusion

far from extensive. Although remaining extremely

cautious around food, he had been able to improve ARFID is a new diagnosis, envisaged as encompass-

the nutritional adequacy of his intake by agreeing ing a number of commonly described clinically sig-

to take a multi-vitamin and iron supplement and nificant feeding and eating disturbances across the

adding yoghurt and smoothies. The latter were age range. As a Feeding and Eating Disorder diagno-

selected on the basis of their color, texture, and sis in DSM-5, it is reserved for presentations that

similarity in taste to the probiotic drink he was al- fulfill the accompanying definition of ‘‘mental disor-

ready having as well as in relation to deficits in his der,’’ which requires ‘‘significant dysfunction in the

diet, in particular calcium and vitamins. He was individual’s cognitions, emotions, or behaviors."7 As

also able to eat French fries, which he had selected a new diagnosis, there is much room for testing

empirically supported treatments specifically with

as useful socially. His growth velocity had improved

this population. B’s presentation has been used to

with height increasing from the 10th to the 35th

illustrate an example of an ARFID presentation, yet

centile, and he had learned to manage his anxiety

cannot be regarded as ‘‘typical" in the absence of a

better when faced with unfamiliar foods, through more robust body of evidence about the disorder.

using breathing and progressive muscle relaxation The clinical utility of the criteria, in particular their

techniques. B’s motivation and focus fluctuated ability to inform clinicians about likely prognosis,

during treatment, as did that of his parents. appropriate treatment interventions and possible

outcomes now requires comprehensive evaluation.

The author was a member of the DSM-5 Eating Disor-

Discussion of ARFID Treatment and ders Work Group. No disclosures or conflict of interests

Intervention to declare.

It is impossible to give a ‘‘typical" description of

ARFID as this diagnosis covers a range of different

clinical presentations. Treatment needs are likely to

References

vary across individuals and, as a rule of thumb, are

1. American Psychiatric Association. Proposed Criteria for Feeding

generally informed by the main areas of impact of and Eating Disorders, 2012. Available from http://

the avoidance or restriction of food intake. These www.dsm5.org/proposedrevision/Pages/Feedingandeatingdisor-

include the extent of nutritional compromise, the ders.aspx. Last accessed on October 31, 2012.

impact on weight (and growth in children), and in- 2. Uher R, Rutter M, Uher R, Rutter M. Classification of feeding and

eating disorders: Review of evidence and proposals for ICD-10.

terference with social and emotional development

World Psychiatry 2012;11:80–92.

or function, with associated distress or impairment. 3. Pine DS, Costello EJ, Dahl R, James R, Leckman JF, Leibenluft E,

Treatment will commonly include psychological et al. Increasing the developmental focus in DSM-5: Broad

interventions, nutritional advice or intervention, issues and specific potential applications in anxiety. In: Regier

and medical monitoring or intervention. Some DA, Narrow WE, Kuhl EA, Kupfer DJ, editors. The Conceptual

Evolution of DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub-

individuals with ARFID may present with extreme lishing, Inc, 2011, p. 305–321.

low weight, resulting in similar complications to 4. Bryant-Waugh R, Markham L, Kreipe R, Walsh BT. Feeding and

people with anorexia nervosa. Others, like B, may eating disorders in childhood. Int J Eat Dis 2010;43:98–111.

present with longstanding serious nutritional com- 5. Thomas JJ, Vartanian LR, Brownell KD. The relationship between

promise, impairing physical development and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) and officially

recognized eating disorders: Meta-analysis and implications for

functioning. In many cases it will be neither realis-

DSM. Psychol Bull 2009;135:407–433.

tic nor necessarily desirable to achieve an eating 6. Chatoor I, Hirsch R, Wonderlich S, Crosby R. Validation of a diag-

pattern without any avoidance or restriction. A nostic classification of feeding disorders in infants and young

more appropriate aim may be to minimize physical children. In: Striegel-Moore R, Wonderlich S, Walsh BT, Mitchell

or nutritional risk through behavioral change and/ J, editors. Developing an Evidence Based Classification of Eating

Disorders: Scientific Findings for DSM-5. Washington, DC: Ameri-

or to help the individual learn to manage their own

can Psychiatric Association, 2011, p. 185–202.

anxiety about trying new foods or extending their 7. American Psychiatric Association. Definition of a Mental Disorder,

dietary intake. 2012. Available from http://www.dsm5.org/proposedrevisions/pages/

proposedrevision.aspx?rid5465. Last accessed on October 31, 2012.

International Journal of Eating Disorders 46:5 420–423 2013 423

Você também pode gostar

- The Clinician's Guide to Oppositional Defiant Disorder: Symptoms, Assessment, and TreatmentNo EverandThe Clinician's Guide to Oppositional Defiant Disorder: Symptoms, Assessment, and TreatmentNota: 2.5 de 5 estrelas2.5/5 (2)

- Arfid, 2017Documento9 páginasArfid, 2017Camilla ValeAinda não há avaliações

- Characteristics of Avoidant-Restrictive Food Intake Disorder in A General Pediatric Inpatient SampleDocumento49 páginasCharacteristics of Avoidant-Restrictive Food Intake Disorder in A General Pediatric Inpatient SampleAmiLia CandrasariAinda não há avaliações

- Teenage Health Concerns: How Parents Can Manage Eating Disorders In Teenage ChildrenNo EverandTeenage Health Concerns: How Parents Can Manage Eating Disorders In Teenage ChildrenAinda não há avaliações

- ARFIDDocumento11 páginasARFIDPirandello100% (1)

- School Refusal: Children Who Can't or Won't Go to SchoolNo EverandSchool Refusal: Children Who Can't or Won't Go to SchoolAinda não há avaliações

- Handouts ARFID PDFDocumento4 páginasHandouts ARFID PDFBM100% (1)

- National Eating Disorders Association's Parent ToolkitDocumento76 páginasNational Eating Disorders Association's Parent ToolkitKOLD News 13100% (1)

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo EverandOppositional Defiant Disorder, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Ross Green - Advanced Explosive Child - Options For Handing ProblemsDocumento9 páginasRoss Green - Advanced Explosive Child - Options For Handing ProblemsTed IndykAinda não há avaliações

- Pda Teachers GuideDocumento2 páginasPda Teachers Guidepeasyeasy100% (2)

- A.D.D., Irritability and Oppositional Disorders: Cutting-Edge SolutionsNo EverandA.D.D., Irritability and Oppositional Disorders: Cutting-Edge SolutionsAinda não há avaliações

- ADHD Symptoms and Personality Relationships With The Five-Factor ModelDocumento11 páginasADHD Symptoms and Personality Relationships With The Five-Factor ModelfabiotheotoAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Lifespan PerspectiveNo EverandDiagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Lifespan PerspectiveAinda não há avaliações

- Common Questions About Oppositional Defiant Disorder - American Family PhysicianDocumento12 páginasCommon Questions About Oppositional Defiant Disorder - American Family Physiciando lee100% (1)

- Developmental Pathways to Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct DisordersNo EverandDevelopmental Pathways to Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct DisordersAinda não há avaliações

- Adhd ChildDocumento72 páginasAdhd Childamdsam100% (1)

- ADHD Not Just Naughty: One mum's roadmap through the early challenges of ADHDNo EverandADHD Not Just Naughty: One mum's roadmap through the early challenges of ADHDAinda não há avaliações

- Case 18-2017 - An 11-Year-Old Girl With Difficulty Eating After A Choking Incident-2017Documento10 páginasCase 18-2017 - An 11-Year-Old Girl With Difficulty Eating After A Choking Incident-2017Juan ParedesAinda não há avaliações

- Collaborative Problem Solving: An Evidence-Based Approach to Implementation and PracticeNo EverandCollaborative Problem Solving: An Evidence-Based Approach to Implementation and PracticeAlisha R. PollastriAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Adhd 2001 (Revised Edition) - PsychiatryDocumento5 páginasUnderstanding Adhd 2001 (Revised Edition) - Psychiatryzaferyha0% (2)

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersNo EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Understanding Oppositional-Defiant Disorder: What Is It?Documento8 páginasUnderstanding Oppositional-Defiant Disorder: What Is It?Abhilash PaulAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Autism?: Understanding Life with Autism or Asperger'sNo EverandWhat Is Autism?: Understanding Life with Autism or Asperger'sAinda não há avaliações

- Kazdin - Parent Management Training Treatment For Oppositional Aggressive and AntisocialDocumento559 páginasKazdin - Parent Management Training Treatment For Oppositional Aggressive and AntisocialANDREA HENAO100% (1)

- Alan L. Berman, David A. Jobes, Morton M. Silverman-Adolescent Suicide - Assessment and Intervention 2nd Edition (2006)Documento453 páginasAlan L. Berman, David A. Jobes, Morton M. Silverman-Adolescent Suicide - Assessment and Intervention 2nd Edition (2006)Mati Mali100% (2)

- The Family ADHD Solution: A Scientific Approach to Maximizing Your Child's Attention and Minimizing Parental StressNo EverandThe Family ADHD Solution: A Scientific Approach to Maximizing Your Child's Attention and Minimizing Parental StressAinda não há avaliações

- The Attwood's System: Asperger's and Emotion ManagementDocumento18 páginasThe Attwood's System: Asperger's and Emotion ManagementEduard CBAinda não há avaliações

- Navigating the Spectrum: A Parent's Guide to Autism in ChildrenNo EverandNavigating the Spectrum: A Parent's Guide to Autism in ChildrenAinda não há avaliações

- FasdDocumento23 páginasFasdapi-351480846Ainda não há avaliações

- The Clinician's Guide to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Childhood Obsessive-Compulsive DisorderNo EverandThe Clinician's Guide to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Childhood Obsessive-Compulsive DisorderEric A. StorchAinda não há avaliações

- The Diagnosis and Treatment of AdhdDocumento116 páginasThe Diagnosis and Treatment of AdhdrajvolgaAinda não há avaliações

- The ADD and ADHD Cure: The Natural Way to Treat Hyperactivity and Refocus Your ChildNo EverandThe ADD and ADHD Cure: The Natural Way to Treat Hyperactivity and Refocus Your ChildAinda não há avaliações

- ADHD Booklet PDF May 2020Documento22 páginasADHD Booklet PDF May 2020Madewo Benjamin100% (1)

- The Identification of Autistic Adults’ Perception of Their Own Diagnostic Pathway: A Research Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of Master of Autism at Sheffield Hallam UniversityNo EverandThe Identification of Autistic Adults’ Perception of Their Own Diagnostic Pathway: A Research Dissertation Submitted for the Degree of Master of Autism at Sheffield Hallam UniversityAinda não há avaliações

- Self Regulation BookletDocumento2 páginasSelf Regulation Bookletapi-273800431Ainda não há avaliações

- Adhd Workshop Gpa 2016 041016c2Documento128 páginasAdhd Workshop Gpa 2016 041016c2meiraimAinda não há avaliações

- ADHD Treatment: Subtypes and ComorbidityDocumento22 páginasADHD Treatment: Subtypes and ComorbiditydionysiaAinda não há avaliações

- Developing Images: Mind Development, Hallucinations and All Mind Disorders Including AutismNo EverandDeveloping Images: Mind Development, Hallucinations and All Mind Disorders Including AutismAinda não há avaliações

- Guidance For Autism-What Should You KnowDocumento7 páginasGuidance For Autism-What Should You KnowPatrickAinda não há avaliações

- CBT For Eating Disorders and Body Dysphoric Disorder: A Clinical Psychology Introduction For Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Eating Disorders And Body Dysphoria: An Introductory SeriesNo EverandCBT For Eating Disorders and Body Dysphoric Disorder: A Clinical Psychology Introduction For Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Eating Disorders And Body Dysphoria: An Introductory SeriesAinda não há avaliações

- Oppositional Defiant DisorderDocumento23 páginasOppositional Defiant DisorderEmily Eresuma100% (2)

- ADHD For Children-AdolescentsDocumento28 páginasADHD For Children-AdolescentsEdgar Prieto AmaralAinda não há avaliações

- PDA Manual PDFDocumento40 páginasPDA Manual PDFSue Griffiths100% (2)

- Living With Autism: Establishing Positive Sleep PatternsDocumento4 páginasLiving With Autism: Establishing Positive Sleep PatternsanacrisnuAinda não há avaliações

- Ahdh DSM5Documento53 páginasAhdh DSM5Sara Araujo100% (1)

- A NEATS Analysis of Childhood ADHDDocumento9 páginasA NEATS Analysis of Childhood ADHDJane GilgunAinda não há avaliações

- Fasd Information HandbookDocumento22 páginasFasd Information Handbookapi-238091952Ainda não há avaliações

- Adhd Rating ScaleDocumento1 páginaAdhd Rating Scaleabu ubaidahAinda não há avaliações

- Clinicians Guide To AutismDocumento20 páginasClinicians Guide To AutismNadia Desanti RachmatikaAinda não há avaliações

- Overcoming Medical Phobias1Documento175 páginasOvercoming Medical Phobias1Hd Laura100% (1)

- Pda Awareness Matters Booklet 2016 Revised Edition Web VersionDocumento36 páginasPda Awareness Matters Booklet 2016 Revised Edition Web VersionCristina100% (2)

- Understanding POTS - The Invisible IllnessDocumento10 páginasUnderstanding POTS - The Invisible IllnessSpencer100% (1)

- A Cool Kids Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Group For Youth With Anxiety Disorders - Part 1, The Case of ErikDocumento57 páginasA Cool Kids Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Group For Youth With Anxiety Disorders - Part 1, The Case of Erikferreira.pipe3240Ainda não há avaliações

- WFBP Guidelines PDFDocumento66 páginasWFBP Guidelines PDFAnonymous fPQaCe8Ainda não há avaliações

- Eating Ones Words III PDFDocumento17 páginasEating Ones Words III PDFAnonymous fPQaCe8Ainda não há avaliações

- Eating Ones Words III PDFDocumento17 páginasEating Ones Words III PDFAnonymous fPQaCe8Ainda não há avaliações

- MBT Training Theory PDFDocumento52 páginasMBT Training Theory PDFAnonymous fPQaCe8Ainda não há avaliações

- Attachment and BPD PDFDocumento19 páginasAttachment and BPD PDFAnonymous fPQaCe8100% (1)

- Bridging The Transmission GapDocumento12 páginasBridging The Transmission GapEsteli189Ainda não há avaliações

- Important Numbers For SMLEDocumento3 páginasImportant Numbers For SMLEAkpevwe EmefeAinda não há avaliações

- PhysioEx Exercise 7 Activity 1Documento6 páginasPhysioEx Exercise 7 Activity 1Jorge CuevaAinda não há avaliações

- Complications of MalariaDocumento12 páginasComplications of MalariaAneesh MyneniAinda não há avaliações

- Disability Mangt PDFDocumento137 páginasDisability Mangt PDFSankitAinda não há avaliações

- Bangladesh Doctors ListDocumento325 páginasBangladesh Doctors ListSadika Jofin75% (12)

- ORAL CANCER - Edited by Kalu U. E. OgburekeDocumento400 páginasORAL CANCER - Edited by Kalu U. E. Ogburekeعبد المنعم مصباحيAinda não há avaliações

- Test Bank For Basic Pharmacology For Nursing 17th EditionDocumento10 páginasTest Bank For Basic Pharmacology For Nursing 17th EditionUsman HaiderAinda não há avaliações

- GMR 2019Documento6 páginasGMR 2019arvindat14Ainda não há avaliações

- Wheezing, Bronchiolitis, and BronchitisDocumento12 páginasWheezing, Bronchiolitis, and BronchitisMuhd AzamAinda não há avaliações

- Health Talk TopicsDocumento3 páginasHealth Talk Topicsvarshasharma0562% (13)

- Chorionic Bump in First-Trimester Sonography: SciencedirectDocumento6 páginasChorionic Bump in First-Trimester Sonography: SciencedirectEdward EdwardAinda não há avaliações

- Question Bank - IinjuriesnjuriesDocumento7 páginasQuestion Bank - IinjuriesnjuriesSapna JainAinda não há avaliações

- Moving Organizational Theory in Health Care.11Documento12 páginasMoving Organizational Theory in Health Care.11Madhan KraceeAinda não há avaliações

- Staffing Power Point Final EditionDocumento36 páginasStaffing Power Point Final EditionAnusha VergheseAinda não há avaliações

- F 16 CLINNeurologicalObservationChartDocumento2 páginasF 16 CLINNeurologicalObservationChartRani100% (1)

- The Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance in BacteriaDocumento2 páginasThe Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance in Bacteriazz0% (1)

- The Andrew Wakefield CaseDocumento3 páginasThe Andrew Wakefield Caseapi-202268486Ainda não há avaliações

- Thesis Topics in Pediatrics in RguhsDocumento8 páginasThesis Topics in Pediatrics in Rguhssarahgriffinbatonrouge100% (2)

- Periodontal and Prosthetic Aspect of Biological WidthDocumento3 páginasPeriodontal and Prosthetic Aspect of Biological WidthFlorence LauAinda não há avaliações

- Ijarbs 14Documento12 páginasIjarbs 14amanmalako50Ainda não há avaliações

- Proforma For Students Credit Card Medical CollegeDocumento8 páginasProforma For Students Credit Card Medical CollegeKriti SinhaAinda não há avaliações

- Rheumatic FeverDocumento61 páginasRheumatic FeverCostea CosteaAinda não há avaliações

- Volume 05 No.1Documento28 páginasVolume 05 No.1Rebin AliAinda não há avaliações

- Sustained and Controlled Release Drug Delivery SystemsDocumento28 páginasSustained and Controlled Release Drug Delivery SystemsManisha Rajmane100% (2)

- Sourav Das, Roll No 23, Hospital PharmacyDocumento17 páginasSourav Das, Roll No 23, Hospital PharmacySourav DasAinda não há avaliações

- Gabriel D. Vasilescu 68 Dorchester Road Ronkonkoma, Ny 11779Documento3 páginasGabriel D. Vasilescu 68 Dorchester Road Ronkonkoma, Ny 11779Meg Ali AgapiAinda não há avaliações

- FwprogrammeDocumento38 páginasFwprogrammeSujatha J Jayabal87% (15)

- 05092016ybct 2ND EdDocumento42 páginas05092016ybct 2ND Edpwilkers36100% (4)

- Inclisiran ProspectoDocumento12 páginasInclisiran ProspectoGuillermo CenturionAinda não há avaliações

- Repertory of Miasms H 36011Documento32 páginasRepertory of Miasms H 36011Fazal Akhtar100% (3)

- Breaking Addiction: A 7-Step Handbook for Ending Any AddictionNo EverandBreaking Addiction: A 7-Step Handbook for Ending Any AddictionNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (2)

- Alcoholics Anonymous, Fourth Edition: The official "Big Book" from Alcoholic AnonymousNo EverandAlcoholics Anonymous, Fourth Edition: The official "Big Book" from Alcoholic AnonymousNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (22)

- Allen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductNo EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Vaping: Get Free from JUUL, IQOS, Disposables, Tanks or any other Nicotine ProductNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (31)

- Self-Love Affirmations For Deep Sleep: Raise self-worth Build confidence, Heal your wounded heart, Reprogram your subconscious mind, 8-hour sleep cycle, know your value, effortless healingsNo EverandSelf-Love Affirmations For Deep Sleep: Raise self-worth Build confidence, Heal your wounded heart, Reprogram your subconscious mind, 8-hour sleep cycle, know your value, effortless healingsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (6)

- Save Me from Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, and Lived to Tell My StoryNo EverandSave Me from Myself: How I Found God, Quit Korn, Kicked Drugs, and Lived to Tell My StoryAinda não há avaliações

- 12 Step Spirituality: Every Person’s Guide to Taking the Twelve StepsNo Everand12 Step Spirituality: Every Person’s Guide to Taking the Twelve StepsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (17)

- Healing Your Aloneness: Finding Love and Wholeness Through Your Inner ChildNo EverandHealing Your Aloneness: Finding Love and Wholeness Through Your Inner ChildNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (9)

- Allen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Smoking Without Willpower: The best-selling quit smoking method updated for the 21st centuryNo EverandAllen Carr's Easy Way to Quit Smoking Without Willpower: The best-selling quit smoking method updated for the 21st centuryNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (47)

- The Heart of Addiction: A New Approach to Understanding and Managing Alcoholism and Other Addictive BehaviorsNo EverandThe Heart of Addiction: A New Approach to Understanding and Managing Alcoholism and Other Addictive BehaviorsAinda não há avaliações

- Twelve Steps and Twelve Traditions: The “Twelve and Twelve” — Essential Alcoholics Anonymous readingNo EverandTwelve Steps and Twelve Traditions: The “Twelve and Twelve” — Essential Alcoholics Anonymous readingNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (11)

- Living Sober: Practical methods alcoholics have used for living without drinkingNo EverandLiving Sober: Practical methods alcoholics have used for living without drinkingNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (50)

- Easyway Express: Stop Smoking and Quit E-CigarettesNo EverandEasyway Express: Stop Smoking and Quit E-CigarettesNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (15)

- Intoxicating Lies: One Woman’s Journey to Freedom from Gray Area DrinkingNo EverandIntoxicating Lies: One Woman’s Journey to Freedom from Gray Area DrinkingNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Allen Carr's Quit Drinking Without Willpower: Be a happy nondrinkerNo EverandAllen Carr's Quit Drinking Without Willpower: Be a happy nondrinkerNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (8)

- The Stop Drinking Expert: Alcohol Lied to Me Updated And Extended EditionNo EverandThe Stop Drinking Expert: Alcohol Lied to Me Updated And Extended EditionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (63)

- Addiction and Grace: Love and Spirituality in the Healing of AddictionsNo EverandAddiction and Grace: Love and Spirituality in the Healing of AddictionsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (11)

- THE FRUIT YOU’LL NEVER SEE: A memoir about overcoming shame.No EverandTHE FRUIT YOU’LL NEVER SEE: A memoir about overcoming shame.Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (7)