Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Pdflib Plop: PDF Linearization, Optimization, Protection Page Inserted by Evaluation Version

Enviado por

Lastry WardaniTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Pdflib Plop: PDF Linearization, Optimization, Protection Page Inserted by Evaluation Version

Enviado por

Lastry WardaniDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

PDFlib PLOP: PDF Linearization, Optimization, Protection

Page inserted by evaluation version

www.pdflib.com – sales@pdflib.com

CLINICAL PRACTICE

A Review of Ludwig’s Angina for Nurse Practitioners

Sandra Winters, MSN, APRN, CNA, BC

INTRODUCTION

Purpose

To discuss the causative factors, clinical course, Although uncommon, Ludwig’s angina can be a potentially life-threaten-

and current treatment modalities for Ludwig’s ing infection of the submandibular, sublingual, and submental spaces.

angina, a submandibular cellulitis, and to raise Wilhelm von Ludwig first described this condition in 1836 as a gangrenous

nurse practitioners’ (NPs’) awareness of this induration of the soft tissues of the neck and floor of the mouth with

condition. “woody” cellulitis (Busch & Shah, 1997; Schreiner & Calhoun, 1999). A

significant decline in the mortality rate has occurred since the preantibiotic

Data Sources era, but Ludwig’s angina remains a clinical emergency as a result of its intrin-

Recent clinical articles, research, case studies, sic development of airway obstruction (Barakate, Hemli, Jensen, & Graham,

and medical texts. 2001). Improved outcomes result from airway protection and aggressive

antimicrobial therapy when instituted early in the course of infection.

Conclusions A primary care nurse practitioner (NP) may be the first health care

Ludwig’s angina may be fatal. Early diagnosis, provider a patient consults with complaints of fever, malaise, and painful

aggressive antibiotic therapy, and management neck swelling. Prompt recognition of these and more definitive characteris-

involving a multidisciplinary team approach tic signs and symptoms of Ludwig’s angina, combined with a good history

are imperative for the patient to progress with- and physical examination, will allow the patient a better chance for a suc-

out complications. cessful outcome. NPs must diagnose deep neck infections early and refer

promptly to emergency treatment. Patients are best treated by a team of

Implications for Practice providers, including an otolaryngologist, an infectious disease specialist, and

Education and awareness are crucial for suc- a dentist (Nicklaus & Kelley, 1996). This article discusses the causes and risk

cessful diagnosis of and management of treat- factors, clinical presentation, clinical course, and current treatment of

ment for Ludwig’s angina. Although NPs have Ludwig’s angina in order to enhance NPs’ knowledge base and ability to

a limited role in the treatment of Ludwig’s diagnose this life-threatening condition.

angina, their ability to recognize the signs and

symptoms will prompt emergency care and

treatment and facilitate better outcomes for CAUSES AND RISK FACTORS

their clients.

Patients affected by submandibular space infections are usually young,

Key Words previously healthy adults with oral or odontogenic infections, most com-

Ludwig’s angina, odontogenic infection, deep monly originating in an infected lower molar (Durand, Joseph, & Sullivan-

neck infection. Baker, 1998; Khanna & Ost, 2002; Schreiner & Calhoun, 1999). Moreland,

Corey, and McKenzie’s (1988) review of 141 cases of Ludwig’s angina

Author demonstrated that some form of dental disorder was the initiating event in

Sandra Winters, MSN, APRN, CNA, BC is a 85% of the cases. Five of the six patients described by Busch and Shah

Family Nurse Practitioner at Whites Crossing (1997) sought treatment for infected mandibular teeth. An additional review

Medical Center in Carbondale, PA. Contact Ms. of 41 Ludwig’s angina cases (Kurien, Mathew, Job, & Zachariah, 1997)

Winters by e-mail at kswinters@pikeonline.net. showed that 52% of the adult cases had associated dental caries; conversely,

the children in the study, ranging in age from 5 months to 12 years, had no

significant associated illness or complication.

Other, less common causes include epiglottitis, oral lacerations, sub-

mandibular sialadenitis, and peritonsillar or parapharyngeal abscesses

(Barakate et al., 2001; Busch & Shah, 1997; Lerner & Troost, 1991). A post-

traumatic infection resulting from a compound mandibular fracture, an

infiltrating injury to the floor of the mouth, or even traumatic intubation

546 VOLUME 15, ISSUE 12, DECEMBER 2003

have preceded Ludwig’s angina (Ferrera, Busino, & Snyder, of the infection. Khanna and Ost (2002) recommended blood

1996; Lerner & Troost; Moreland et al., 1988). Perkins, Meisner, cultures obtaining for both aerobic and anaerobic organisms.

and Harrison (1997) documented a case of Ludwig’s angina sec- Although plain radiographs of the neck are limited in diagnos-

ondary to a recent tongue piercing. In perhaps the most disturb- ing or defining deep neck abscesses, they may demonstrate the

ing scenario, no causative agent or factor could be identified extent of soft tissue swelling (Barakate et al., 2001; Nicklaus &

(Khanna & Ost, 2002). Kelley, 1996). Chest radiography can reveal extension of the

Although, the majority of Ludwig’s angina cases occur in pre- infective process into the mediastinum or lungs (Khanna & Ost;

viously healthy individuals, there are certain coexisting condi- Nicklaus & Kelley). Ultrasonography can distinguish location,

tions that may predispose patients to severe submandibular size, and collections of pus and may reveal metastatic abscess for-

infection. These include, but are not limited to, diabetes melli- mation (Barakate et al., 2001; Nicklaus & Kelley).

tus, neutropenia, aplastic anemia, glomerulonephritis, dermato- Ultrasonography can be particularly helpful in children because

myositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and altered immunode- it is noninvasive and involves no radiation; it can also be useful

ficiency states (Busch & Shah, 1997; Khanna & Ost, 2002; in localization of abscesses for needle aspiration (Nicklaus &

Pizzo, 1999). Khanna and Ost conceded that because of the low Kelley). Computed tomography (CT) is probably the most

incidence of Ludwig’s angina, these associations lack convincing widely used imaging modality because it can provide the best

support and are more anecdotal. radiological evaluation of a deep neck abscess (Healy, 1989).

The causative organisms are varied and often mixed and Areas of fluid collection, spread of infection, and degree of air-

include aerobes and anaerobes. Busch and Shah (1997) report way restriction may be detected with CT (Khanna & Ost).

alpha-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci, and bacteroides as Miller, Furst, Sandor, and Keller (1999) conducted a study to

the most commonly reported organisms. Besides Bacteroides determine whether there is a scientific basis for the routine use

melaninogenicus and Bacteroides oralis, anaerobes such as of contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) in the evaluation of suspect-

Peptostreptococcus, Peptococcus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, ed deep neck infection. They concluded that CT used alone in

Veillonella, and spirochetes are additionally reported (Busch & determination of deep neck infections has a high sensitivity and

Shah; Moreland et al., 1988). Hartmann (1999) documents that low specificity; thus, its use may lead to unnecessary surgery for

a foul breath odor usually indicates the presence of an anaerobe. some patients. Therefore, clinical examination combined with

There are also documented cases of gram-negative organisms such CECT is the most accurate method to determine the extent of

as Neisseria catarrhalis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, deep neck infections. Magnetic resonance imaging may provide

and Haemophilus influenzae (Busch & Shah; Moreland et al.). superior resolution of soft tissues compared to CECT, but mag-

netic resonance imaging has the disadvantage of lengthy imaging

times, which can be extremely dangerous to a patient with a pos-

CLINICAL PRESENTATION sible airway compromise (Nicklaus & Kelley).

Subjective characteristics of Ludwig’s angina include a com-

plaint of mouth and/or tooth pain with a possible history of CLINICAL COURSE

recent dental extraction or poor dental hygiene (Moreland et al.,

1988). Constitutional symptoms of fever and malaise are com- Ludwig’s angina is a bilateral cellulitis of the submandibular

mon. Dysphagia and drooling are also common, and some space that attacks the connective tissue, fascia, and muscles but

patients may experience severely painful swallowing (Schreiner not the glandular structures (Nicklaus & Kelley, 1996). The sub-

& Calhoun, 1999). Essentially all patients experience severe mandibular space extends from the hyoid bone to the floor of

neck pain, stiffness, and swelling (Sethi & Stanley, 1994). Some the mouth and is composed of two spaces, the sublingual space

individuals display dysphonia and/or dysarthria, which and the submaxillary space. Clinically, these two spaces function

Schreiner and Calhoun describe as a “hot potato” voice. as one because of their free intercommunication and their com-

Physical examination may reveal fever and tachycardia with a mon clinical signs and symptoms (Linder, 1986). The buc-

characteristic firm, woody, hard mouth floor (Barakate et al., copharyngeal gap, which is created by the styloglossus muscle

2001; Kurien et al., 1997). Carious molar teeth may also be pre- passing between the middle and superior constrictors, is a poten-

sent (Hartmann, 1999). An induration and swelling of the sub- tially dangerous connection between the submandibular and lat-

mandibular space combined with an elevated, protruding tongue eral pharyngeal spaces (Schreiner & Calhoun, 1999). Ludwig’s

is generally observed. Trismus can also occur and indicates direct angina infection spreads directly via the buccopharyngeal gap to

irritation of the masticatory muscles (Barakate et al., 2001; the lateral pharyngeal space, where the cellulitis is increasingly

Schulman & Owens, 1996). Any indication of dyspnea, tachyp- dangerous (Schreiner & Calhoun) and can cause a life-threaten-

nea, inspiratory stridor, and cyanosis are signs of impending air- ing airway obstruction.

way obstruction and indicate a medical emergency (Marple, Because the anatomic barriers are relatively unrestricted, the

1999). infection can spread easily to other tissues in the neck, to the

Although the diagnosis of Ludwig’s angina is usually clear-cut retropharyngeal fascial space, and, infrequently, to mediastinum or

based on the history and physical examination, a number of subphrenic space (Barakate et al., 2001). In addition to airway

imaging methods are nonetheless useful in defining the severity compromise, which can occur at any time and without warning,

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF NURSE PRACTITIONERS 547

complications of Ludwig’s angina can include cavernous sinus considered (Khanna & Ost, 2002; Sandor, Low, Judd, &

thrombosis from the infection in the facial venous system, aspira- Davidson, 1998). Blood culture and fluid culture results will

tion of infected secretions, and subphrenic abscess formation. help to optimize treatment regimens (Khanna & Ost).

Further reported complications include mediastinitis, pericardial Decompression of the submandibular, sublingual, and sub-

and/or pleural effusion, empyema, infection of the carotid sheath mental spaces can be accomplished with through-and-through

with possible rupture of the carotid artery, and suppurative throm- drains by using a single submental incision (Busch & Shah,

bophlebitis of the internal jugular vein (Barakate et al.; Ferrera et 1997) in the setting of suppurative infection (Barakate et al.,

al., 1996; Furst, Ersil, & Caminiti, 2001; Stewart, 2000). 2001). Indications for surgical drainage include fluctuance,

crepitus, and the presence of soft tissue air (Ferrera et al., 1996;

Lerner & Troost, 1991; Patterson, Kelly, & Strome, 1982).

MANAGEMENT Generally, the incision is made parallel and 3 cm inferior to the

angle of the mandible. Size and location of the initial incision

Management of Ludwig’s angina requires three areas of con- depend on the specific anatomic spaces involved, and extension

centration. First and foremost is the maintenance of a patent air- to the midline below the chin may be needed in severe cases

way. Second, aggressive antibiotic therapy is required to treat and (Barakate et al.). In addition to decompression of all closed fas-

limit the spread of infection. And third, decompression of the cial spaces of the neck, another goal of surgical drainage is evac-

submandibular, sublingual, and submental spaces should be per- uation of pus (Barakate et al.). If an infected tooth is the culprit

formed in some cases (Busch & Shah, 1997). of the initiating event, it must be extracted to promote complete

Tracheostomy was once thought to be necessary in most drainage (Barakate et al.).

patients, but with the advent of better intubation techniques and

fiber-optic endotracheal tube placement, the necessity of tra-

cheostomy has decreased (Khanna & Ost, 2002). Intubation SUMMARY

may require nasal intubation using a flexible telescope with the

patient awake and in an upright position (Busch & Shah, 1997). Ludwig’s angina is a potentially fatal infection. Although seen

If this is not possible, cricothyroidotomy or tracheotomy under with less frequency because of improved dental care and antibi-

local anesthesia may be necessary (Busch & Shah). Since the otic therapy, it remains a significant threat to those with limited

aggressive use of antibiotics, airway observation has become a access or opportunity for dental care (Busch & Shah, 1997). NPs

more popular option, particularly if the patient is in an optimal need to be able to recognize the clinical features of Ludwig’s

facility with skilled and experienced staff available to perform angina in order to provide the prompt emergency care required

emergency surgical airway patency (Marple, 1999; Neff, Merry, for these clients. Early diagnosis, airway management, and

& Anderson, 1999). appropriate referral are the crucial first actions for NPs; collabo-

Khanna and Ost (2002) discussed the use of a trial of heliox rative management by a specialist team with antibiotic therapy,

in patients who had early upper airway compromise. Heliox, a and surgical drainage if required, is essential for Ludwig’s angina

low-density helium-oxygen mixture, reduces the work of breath- to resolve without complications.

ing by reducing the large pressure drop associated with turbulent

flow across the obstruction. This mixture has been useful in the REFERENCES

treatment of other conditions affiliated with airway compromise, Barakate, M. S., Hemli, J. M., Jensen, M. J., & Graham, A. R. (2001). Ludwig’s

although no controlled trials exist with the condition of Ludwig’s angina: Report of a case and review of management issues. Annals of

angina. Heliox may be a useful temporizing measure in border- Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology, 110, 453–456.

line patients, as long as appropriate intervention is available in Busch, R. F., & Shah, D. (1997). Ludwig’s angina: Improved treatment.

the event of further airway compromise (Khanna & Ost). Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, 117, S172–S175.

The six patients discussed by Busch and Shah (1997) were Durand, M., Joseph, M., & Sullivan-Baker, A. (1998). Infections of the oral cavi-

initially treated with intravenous dexamethasone for 48 hr, in ty and pharynx. In A. S. Fauci, E. Braunwald, K. J. Isselbacher, J. D. Wilson,

addition to receiving antibiotic therapy and surgical decompres- J. B. Martin, D. L. Kasper, S. L. Hauser, & D. L. Longo (Eds.), Harrison’s prin-

sion. Dexamethasone use allows intubation to be carried out ciples of internal medicine (pp.182–183). New York: McGraw-Hill.

under more controlled conditions, often avoiding the need for Ferrera, P. C., Busino, L. J., & Snyder, H. S. (1996). Uncommon complications of

tracheotomy or cricothyroidotomy. Additionally, they found odontogenic infections. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 14,

that length of hospital stay was reduced with the use of dexam- 317–22.

ethasone. They initially administered 10 mg, followed by 4 mg Furst, I. M., Ersil, P., & Caminiti, M. (2001). A rare complication of tooth abscess:

every 6 hr for 48 hr. Ludwig’s angina and mediastinitis. Journal of the Canadian Dental

After airway patency is secured, intravenous (IV) antibiotic Association, 67(6), 324–327.

should be administered. Historically, high doses of penicillin (2 Hartmann, R. W. (1999). Ludwig’s angina in children. American Family

million to 4 million units IV q4h have been used as the first-line Physician, 60, 109–112.

agent for Ludwig’s angina. With the increasing prevalence of Healy, G. B. (1989). Inflammatory neck masses in children: A comparison of

beta-lactamase production, particularly among Bacteroides computed tomography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging.

species, the addition of metronidazole or clindamycin should be Archives of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, 115, 1027–1028.

548 VOLUME 15, ISSUE 12, DECEMBER 2003

Khanna, D., & Ost, D. (2002). How to identify and manage life-threatening infec- Nicklaus, P. J., & Kelley, P. E. (1996). Management of deep neck infection.

tions of the upper airway: Part 2. The Journal of Critical Illness, 17(4), Pediatric Otolaryngology, 43(6), 1277–1296.

134–140. Patterson, H. C., Kelly, J. H., & Strome, M. (1982). Ludwig’s angina: An update.

Kurien, M., Mathew, J., Job, A., & Zachariah, N. (1997). Ludwig’s angina. Clinical Laryngoscope, 92, 370–378.

Otolaryngology, 22, 263–265. Perkins, C. S., Meisner, J., & Harrison, J. M. (1997). A complication of tongue

Lerner, D. N., & Troost, T. (1991). Submandibular sialadenitis presenting as piercing. British Dental Journal, 182(4), 147–148.

Ludwig’s angina. Ear, Nose, and Throat Journal, 70, 807–809. Pizzo, P. A. (1999). Fever in immunocompromised patients. The New England

Linder, H. H. (1986). The anatomy of the fasciae of the face and neck with par- Journal of Medicine, 341(12), 893–899.

ticular reference to the spread and treatment of intraoral infections Sandor, G. K. B., Low, D. E., Judd, P. I., & Davidson, R. J. (1998). Antimicrobial

(Ludwig’s) that have progressed into adjacent fascial spaces. Annals of treatment options in the management of odontogenic infections. Canadian

Surgery, 204(6), 705–714. Dental Association, 64(7), 508–514.

Marple, B. F. (1999). Ludwig’s angina: A review of current airway management. Schreiner, C., & Calhoun, K. H. (1999). Life-threatening infections of the head

Archives of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, 125, 596–600. and neck: Part 1—Early clues to oral and otogenic involvement. Consultant,

Miller, W. D., Furst, I. M., Sandor, G. K. B., & Keller, A. (1999). A prospective, 39(3), 627–640.

blinded comparison of clinical examination and computed tomography in Schulman, N. J., & Owens, B. (1996). Medical complications following success-

deep neck infections. Laryngoscope, 109, 1873–1879. ful pediatric dental treatment. Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry, 20,

Moreland, L. W., Corey, J., & McKenzie, R. (1988). Ludwig’s angina: Report of a 273–275.

case and review of the literature. Archives of Internal Medicine, 148, Sethi, D. S., & Stanley, R. E. (1994). Deep neck abscesses: Changing trends.

461–466. Journal of Laryngology and Otology, 108, 138–143.

Neff, S. P. W., Merry, A. F., & Anderson, B. (1999). Airway management in Stewart, C. E. (2000). Not just a sore throat. Emergency Medical Services, 29(7),

Ludwig’s angina. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, 27(6), 659–661. 56–66.

NURSE PRACTITIONER VIDEO

on VHS VIDEOTAPE & CD-ROM

Now available for order is a high quality videotape and/or CD-ROM with the special report

about nurse practitioners produced in 2001 by the Academy. This NP special report has

been aired on CNBC, BRAVO and the Health Network. The videotape also includes the video

news release (VNR) that was distributed to over 750 TV stations.

• VHS videotape with both the special report and VNR is $12 *

• CD-ROM with the special report is $10 *

• Together the videotape & CD-ROM are $20 *

* Prices include shipping and handling

ORDER NOW!

For information call: 512-442-4262

E-mail: npvideo@aanp.org

Visit www.aanp.org to download order form

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF NURSE PRACTITIONERS 549

Você também pode gostar

- Polat, G., & Sade, R - 2018. - Radiologic Radiologic Imaging Imaging of Ludwig Angina in A Pediatric Patient. Journal of Craniofacial SurgeryDocumento1 páginaPolat, G., & Sade, R - 2018. - Radiologic Radiologic Imaging Imaging of Ludwig Angina in A Pediatric Patient. Journal of Craniofacial SurgeryFitna TaulanAinda não há avaliações

- Infeccion Focal Newman1996Documento8 páginasInfeccion Focal Newman1996Lucía LGAinda não há avaliações

- 1.focal InfectionsDocumento9 páginas1.focal InfectionsEstherAinda não há avaliações

- Deep Neck Infection: Analysis of 185 Cases: Correspondence To: Y.-S. Chen B 2004 Wiley Periodicals, IncDocumento7 páginasDeep Neck Infection: Analysis of 185 Cases: Correspondence To: Y.-S. Chen B 2004 Wiley Periodicals, IncHiramAinda não há avaliações

- Ludwig 2 PDFDocumento4 páginasLudwig 2 PDFWidyastuti RenaningsihAinda não há avaliações

- Mastoiditis in Childhood: Review of The LiteratureDocumento6 páginasMastoiditis in Childhood: Review of The LiteratureElysabeth MargarethaAinda não há avaliações

- 1 s2.0 S1879729615001064 MainDocumento4 páginas1 s2.0 S1879729615001064 MainMarcelo DiasAinda não há avaliações

- Bronchiolitis Obliterans PDFDocumento7 páginasBronchiolitis Obliterans PDFSatnam KaurAinda não há avaliações

- Infections of the Ears, Nose, Throat, and SinusesNo EverandInfections of the Ears, Nose, Throat, and SinusesMarlene L. DurandAinda não há avaliações

- Submandibular Space Infection: A Potentially Lethal InfectionDocumento7 páginasSubmandibular Space Infection: A Potentially Lethal InfectionAnonymous 9KcGpvAinda não há avaliações

- Fungi PDFDocumento6 páginasFungi PDFnilnaAinda não há avaliações

- Laryngeal Complications of COVID-19Documento8 páginasLaryngeal Complications of COVID-19Mariana BarrosAinda não há avaliações

- Unilateral Tuberculous Otitis Media: Case ReportDocumento4 páginasUnilateral Tuberculous Otitis Media: Case ReportLally RamliAinda não há avaliações

- A Case Report On Ludwig'S Angina: An Ent EmergencyDocumento2 páginasA Case Report On Ludwig'S Angina: An Ent EmergencyvaAinda não há avaliações

- International Journal of Infectious DiseasesDocumento5 páginasInternational Journal of Infectious Diseasesbe a doctor for you Medical studentAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Findings and Management of PertussisDocumento10 páginasClinical Findings and Management of PertussisAGUS DE COLSAAinda não há avaliações

- Vol24 3-3 PDFDocumento7 páginasVol24 3-3 PDFEliasAinda não há avaliações

- AANA Journal Course: Update For Nurse Anesthetists Ludwig Angina: Forewarned Is ForearmedDocumento7 páginasAANA Journal Course: Update For Nurse Anesthetists Ludwig Angina: Forewarned Is ForearmedTyo RizkyAinda não há avaliações

- ADJ-odontogenic InfectionDocumento9 páginasADJ-odontogenic Infectiondr.chidambra.kapoorAinda não há avaliações

- Cervical Necrotizing Fasciitis: Systematic Review and Analysis of 1235 Reported Cases From The LiteratureDocumento9 páginasCervical Necrotizing Fasciitis: Systematic Review and Analysis of 1235 Reported Cases From The Literaturejvw1974Ainda não há avaliações

- Seminar: Olli Ruuskanen, Elina Lahti, Lance C Jennings, David R MurdochDocumento12 páginasSeminar: Olli Ruuskanen, Elina Lahti, Lance C Jennings, David R MurdochChika AmeliaAinda não há avaliações

- BronchioitisDocumento24 páginasBronchioitismitiku aberaAinda não há avaliações

- 15 Submandibular Space Infection A Potentially Lethal Infection PDFDocumento8 páginas15 Submandibular Space Infection A Potentially Lethal Infection PDFAhmad Rifqi RizalAinda não há avaliações

- Murray A.d., Meyers A.D. Deep Neck Infections. Otolaryngology and Facial Plastic SurgeryDocumento17 páginasMurray A.d., Meyers A.D. Deep Neck Infections. Otolaryngology and Facial Plastic SurgeryAndi Karwana CiptaAinda não há avaliações

- Rhinosinusitis Complications: Orbital, Intracranial RisksDocumento10 páginasRhinosinusitis Complications: Orbital, Intracranial RisksdesakAinda não há avaliações

- Ludwig AnginaDocumento3 páginasLudwig AnginaWellyAnggaraniAinda não há avaliações

- A Study On Deep Neck Space InfectionsDocumento6 páginasA Study On Deep Neck Space InfectionsbebetteryesyoucanAinda não há avaliações

- Terapia de Voz en El Contexto de La Pandemia Covid-19 Recomendaciones para La PR Actica ClınicaDocumento12 páginasTerapia de Voz en El Contexto de La Pandemia Covid-19 Recomendaciones para La PR Actica ClınicaLaura Marcela Baldrich CorreaAinda não há avaliações

- THT - 12 Acute Otitis Media and Other Complication of Viral Respiratory InfectionDocumento12 páginasTHT - 12 Acute Otitis Media and Other Complication of Viral Respiratory InfectionWelly SuryaAinda não há avaliações

- Angina Ludwig 2011Documento3 páginasAngina Ludwig 2011Arini Dwi NastitiAinda não há avaliações

- Emergency Management of Ludwig's Angina: A Case Report: Nur H. Alimin, Endang SyamsuddinDocumento4 páginasEmergency Management of Ludwig's Angina: A Case Report: Nur H. Alimin, Endang Syamsuddin송란다Ainda não há avaliações

- 473 1255 1 PBDocumento13 páginas473 1255 1 PBPeter SalimAinda não há avaliações

- Correspondence: Smell and Taste Dysfunction in Patients With COVID-19Documento1 páginaCorrespondence: Smell and Taste Dysfunction in Patients With COVID-19Dhyo Asy-shidiq HasAinda não há avaliações

- Referensi Tesis Spesialis KhalidDocumento7 páginasReferensi Tesis Spesialis KhalidflorensiaAinda não há avaliações

- Inhalational, Gastrointestinal, and Cutaneous Anthrax in ChildrenDocumento12 páginasInhalational, Gastrointestinal, and Cutaneous Anthrax in ChildrenAgungwiraAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Mastoiditis With Temporomandibular Joint EffusionDocumento2 páginasAcute Mastoiditis With Temporomandibular Joint EffusionWidyan Putra AnantawikramaAinda não há avaliações

- Ijcmr 1368 April 23 PDFDocumento3 páginasIjcmr 1368 April 23 PDFIhsan aprijaAinda não há avaliações

- Ludwig's Angina in Children: Jun-Kai Kao, Shun-Cheng YangDocumento4 páginasLudwig's Angina in Children: Jun-Kai Kao, Shun-Cheng YangKarglem David Torres MartínezAinda não há avaliações

- Lipschitz 2017Documento16 páginasLipschitz 2017Yosephine Nina WidyariniAinda não há avaliações

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Ear, Nose, and Throat Description at Acute Stage and After RemissionDocumento6 páginasStevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis Ear, Nose, and Throat Description at Acute Stage and After RemissionElsa Giatri SiradjAinda não há avaliações

- Vega Heredia2011Documento11 páginasVega Heredia2011andiniAinda não há avaliações

- Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivity guide head and neck infection treatmentDocumento13 páginasMicrobiology and antibiotic sensitivity guide head and neck infection treatmentMuhamad SaifuddinAinda não há avaliações

- Otitis ExternaDocumento4 páginasOtitis ExternaCesar Mauricio Daza CajasAinda não há avaliações

- Article in Press: Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and PathologyDocumento7 páginasArticle in Press: Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Medicine, and PathologyNizajaulAinda não há avaliações

- Allergic Fungal Sinusitis - CT FindingsDocumento6 páginasAllergic Fungal Sinusitis - CT Findingssomeone that you used to knowAinda não há avaliações

- Tuberculous Meningitis Review 2010Documento16 páginasTuberculous Meningitis Review 2010SERGIO LOBATO FRANÇAAinda não há avaliações

- Pediatric Chronic Sinusitis Diagnosis and ManagementDocumento10 páginasPediatric Chronic Sinusitis Diagnosis and ManagementcaromoradAinda não há avaliações

- Epidemiology (Introduction)Documento17 páginasEpidemiology (Introduction)M7MD SHOWAinda não há avaliações

- Acute and Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Adults PSO-HNS 2016Documento12 páginasAcute and Chronic Rhinosinusitis in Adults PSO-HNS 2016Angela TakedaAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Isolated Sphenoid Sinusitis in Children - 2021 - International Journal ofDocumento8 páginasAcute Isolated Sphenoid Sinusitis in Children - 2021 - International Journal ofHung Son TaAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Features Diagnosis and ManagemeDocumento9 páginasClinical Features Diagnosis and ManagemeEniola JayeolaAinda não há avaliações

- Management of Paediatric Acute Mastoiditis: Systematic ReviewDocumento9 páginasManagement of Paediatric Acute Mastoiditis: Systematic ReviewAldy GeriAinda não há avaliações

- Deep Neck Space InfectionsDocumento7 páginasDeep Neck Space InfectionsNanda MeidaAinda não há avaliações

- Emergency Medicine:: Pediatric Deep Neck Space Abscesses: A Prospective Observational StudyDocumento6 páginasEmergency Medicine:: Pediatric Deep Neck Space Abscesses: A Prospective Observational StudyG Virucha Meivila IIAinda não há avaliações

- Rare Primary Tuberculosis in TonsilsDocumento3 páginasRare Primary Tuberculosis in Tonsilsmanish agrawalAinda não há avaliações

- Otitis 1Documento1 páginaOtitis 1Raja Friska YulandaAinda não há avaliações

- Parapharyngeal Abscess Is Frequently Associated With Concomitant Peritonsillar AbscessDocumento7 páginasParapharyngeal Abscess Is Frequently Associated With Concomitant Peritonsillar AbscessenrionickolasAinda não há avaliações

- Dentoalveolar InfectionsDocumento10 páginasDentoalveolar InfectionsCristopher Alexander Herrera QuevedoAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar: Diederik Van de Beek, Matthijs C Brouwer, Uwe Koedel, Emma C WallDocumento13 páginasSeminar: Diederik Van de Beek, Matthijs C Brouwer, Uwe Koedel, Emma C WallNestor AmaroAinda não há avaliações

- 142 01 PDFDocumento5 páginas142 01 PDFthonyyanmuAinda não há avaliações

- Microbiologicalcomparison PDFDocumento6 páginasMicrobiologicalcomparison PDFLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Microbiologicalcomparison PDFDocumento6 páginasMicrobiologicalcomparison PDFLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- IDSA Guidelines for DFI Diagnosis and TreatmentDocumento42 páginasIDSA Guidelines for DFI Diagnosis and TreatmentFadilLoveMamaAinda não há avaliações

- 145 266 1 SMDocumento5 páginas145 266 1 SMjemmysenseiAinda não há avaliações

- Tooth Mousse PlusDocumento12 páginasTooth Mousse PlusLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Manifestations in Patients With Gastro-Oesophageal Re Ux Disease A Single-Center Case-Control Study (Palate Erythema)Documento5 páginasOral Manifestations in Patients With Gastro-Oesophageal Re Ux Disease A Single-Center Case-Control Study (Palate Erythema)Lastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Prevalence and Risk Factors of Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy Among IndiansDocumento4 páginasPrevalence and Risk Factors of Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy Among IndiansLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- HipertiroidDocumento6 páginasHipertiroidcalondokterbroAinda não há avaliações

- Picture BiomolDocumento2 páginasPicture BiomolLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Change The Definition of BlindnessDocumento5 páginasChange The Definition of BlindnessDelfi AnggrainiAinda não há avaliações

- Wu Step 2 CK Study PlanDocumento6 páginasWu Step 2 CK Study PlanLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Ephaptic CouplingDocumento1 páginaEphaptic CouplingLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Demam Berdarah DengueDocumento44 páginasDemam Berdarah DengueLastry Wardani100% (2)

- 27 Confusion-ChiriacApdf PDFDocumento3 páginas27 Confusion-ChiriacApdf PDFLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Kualitas Pelayanan Health Care MalaysiaDocumento13 páginasKualitas Pelayanan Health Care MalaysiaLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Depression During Pregnancy Rates Risks and Consequences Motherisk Update 2008Documento8 páginasDepression During Pregnancy Rates Risks and Consequences Motherisk Update 2008Lastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- ServqualDocumento13 páginasServqualLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Diagnosis - of - Hep - C - Update - Aug - 09pdf PDFDocumento41 páginasDiagnosis - of - Hep - C - Update - Aug - 09pdf PDFLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- 0750200101Documento9 páginas0750200101maa_ablAinda não há avaliações

- Service Dimensions of Service Quality Impacting Customer SatisfacDocumento38 páginasService Dimensions of Service Quality Impacting Customer SatisfacLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Factsheet 2007 TBDocumento2 páginasFactsheet 2007 TBLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction to Evidence-Based MedicineDocumento18 páginasIntroduction to Evidence-Based MedicineLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Mna Mini English PDFDocumento1 páginaMna Mini English PDFLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- Evidence Based MedicineDocumento22 páginasEvidence Based MedicineLastry WardaniAinda não há avaliações

- CPR GuidelinesDocumento30 páginasCPR GuidelineswvhvetAinda não há avaliações

- Treatment of Acute BronchitisDocumento3 páginasTreatment of Acute Bronchitisrisma panjaitanAinda não há avaliações

- Current Issues in Spinal AnesthesiaDocumento19 páginasCurrent Issues in Spinal AnesthesiaNadhifah RahmawatiAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of Dispensers in The Rational Use of DrugsDocumento19 páginasThe Role of Dispensers in The Rational Use of DrugsAci LusianaAinda não há avaliações

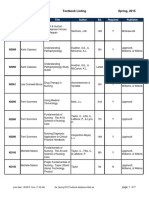

- BFLSON Course Textbook ListingDocumento7 páginasBFLSON Course Textbook ListingWina ViqaAinda não há avaliações

- Patricia DanzonDocumento4 páginasPatricia Danzonranjan tyagiAinda não há avaliações

- 38 The Use of Meta-Analysis in Pharmacoepidemiology: Jesse A. BerlinDocumento27 páginas38 The Use of Meta-Analysis in Pharmacoepidemiology: Jesse A. BerlinFranklin garryAinda não há avaliações

- B Braun Ra - CatalogueDocumento21 páginasB Braun Ra - CatalogueDina Friance ManihurukAinda não há avaliações

- Smith Medical - H-1200 Fast Fluid WarmerDocumento78 páginasSmith Medical - H-1200 Fast Fluid WarmerVictor ȘchiopuAinda não há avaliações

- Disc Bulge Recovery LikelyDocumento4 páginasDisc Bulge Recovery LikelyItai IzhakAinda não há avaliações

- Conventional Tic Failure and Re TreatmentDocumento25 páginasConventional Tic Failure and Re TreatmentBruno Miguel Teixeira QueridinhaAinda não há avaliações

- Weekly Reflective Journal on Gyne Ward and ICU Clinical AreasDocumento2 páginasWeekly Reflective Journal on Gyne Ward and ICU Clinical AreasRowena Marie Endoso BetonioAinda não há avaliações

- APLS Scenario OSCE PDFDocumento5 páginasAPLS Scenario OSCE PDFNikita JacobsAinda não há avaliações

- Module 11 Rational Cloze Drilling ExercisesDocumento9 páginasModule 11 Rational Cloze Drilling Exercisesperagas0% (1)

- SedativesDocumento3 páginasSedativesOana AndreiaAinda não há avaliações

- Fdar Psychiatric DutyDocumento2 páginasFdar Psychiatric DutyErica Maceo MartinezAinda não há avaliações

- Blink Reflex: AnatomyDocumento5 páginasBlink Reflex: AnatomyedelinAinda não há avaliações

- 2015 Sigmoid DiverticulitisDocumento11 páginas2015 Sigmoid DiverticulitisDinAinda não há avaliações

- Internship Self-ReflectionDocumento6 páginasInternship Self-Reflectionapi-485465821Ainda não há avaliações

- Ashley Jones RN ResumeDocumento1 páginaAshley Jones RN Resumeapi-299649525100% (1)

- Pelvic Floor StretchesDocumento4 páginasPelvic Floor StretchesABUBAKARAinda não há avaliações

- The Quest for Conservative and Predictable Esthetic Posterior RestorationsDocumento31 páginasThe Quest for Conservative and Predictable Esthetic Posterior RestorationsJitender Reddy50% (2)

- Medical Prioritization ProcessDocumento20 páginasMedical Prioritization ProcessIGDAinda não há avaliações

- 102 WHO Guidelines On CD4 and VL For ART Doherty PDFDocumento33 páginas102 WHO Guidelines On CD4 and VL For ART Doherty PDFDimar KenconoAinda não há avaliações

- Mad Wife Struck OffDocumento8 páginasMad Wife Struck OffDr John CrippenAinda não há avaliações

- Nonfarmakologi Behaviour ManagementDocumento23 páginasNonfarmakologi Behaviour ManagementSilviana AzhariAinda não há avaliações

- Essential Drugs at PHCDocumento21 páginasEssential Drugs at PHCapi-3823785Ainda não há avaliações

- Family and Pediatric Dentistry Business PlanDocumento27 páginasFamily and Pediatric Dentistry Business PlanSiti Latifah Maharani100% (1)

- Dorothy M. Adcock, MDDocumento4 páginasDorothy M. Adcock, MDพอ วิดAinda não há avaliações