Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Temasek Holdings and Its Governance of Government-Linked Companies (NTU078-PDF-ENG)

Enviado por

rizkielimbongTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Temasek Holdings and Its Governance of Government-Linked Companies (NTU078-PDF-ENG)

Enviado por

rizkielimbongDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

TEMASEK HOLDINGS AND ITS GOVERNANCE OF HBSP No.: NTU078

GOVERNMENT-LINKED COMPANIES Ref No.: ABCC-2016-001

Date: 16 February 2016

Shirley Koh and Boon-Siong Neo

In 1974, Temasek Holdings (“Temasek”) was formed to own and manage the Singapore

government’s shares in business assets on a commercial basis. Temasek’s mandate was to

maximize the value of these assets and investments in the long term. Temasek had a sole

shareholder – the Singapore government through the Minister for Finance (Incorporated),

which was the recipient of its declared dividends, as well as corporate taxes.

Since inception, Temasek had taken on various roles – passive custodian, proactive steward,

engaged shareholder, private equity investor, and active investor, all with the ultimate goal

of creating value in its portfolio to ultimately benefit Singapore as the country went through

structural changes. Between 1974 and 2015, Temasek’s portfolio value had grown from

S$354 million to S$266 billion; while its investments had proliferated from 35 formerly

Singapore government-owned companies to a global portfolio that comprised scores of

companies across diverse geographies and industries. Temasek’s portfolio companies were

guided and managed by their respective boards and management. Temasek’s philosophy was

to promote sound corporate governance in its portfolio companies, but to do so through

active shareholder engagement, not management intervention. One way it did so was in

helping its portfolio companies to form high-quality boards with a majority of independent

directors.

In July 2015, the Singapore Parliament approved adding Temasek as a contributor to the Net

Investment Returns (NIR) framework. This would permit the Singapore government to include

in its annual budget, a maximum of 50% of long-term expected real returns generated from

Temasek’s net assets. One important question that arose from this development was: what

would Temasek’s inclusion into the NIR framework mean for the company and its future?

Research Fellow Shirley Koh and Professor Boon-Siong Neo wrote this case from public sources. This case is

intended for class discussion and learning, and not intended as source research material or as illustration of

effective or ineffective management.

COPYRIGHT © 2016 Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. All rights reserved. No part of this

publication may be copied, stored, transmitted, altered, reproduced or distributed in any form or medium

whatsoever without the written consent of Nanyang Technological University.

The Asian Business Case Centre, Nanyang Business School, Nanyang Technological University, Nanyang

Avenue, Singapore 639798. Phone: +65-6790-4864/6552, E-mail: asiacasecentre@ntu.edu.sg

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 2

ABCC-2016-001

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF SINGAPORE’S ECONOMIC GOVERNANCE

In 1965, Singapore became independent and given its lack of natural resources, economic development

was of utmost priority for the young nation. As the private sector was underdeveloped, the Singapore

government had to assume the role of state entrepreneur in order to “develop economically viable

businesses, retain and create jobs, and contribute to Singapore’s economic survival, progress and

prosperity.” 1 Hence, government-linked companies (GLCs) and government agencies were set up to

provide the infrastructure and services that would support the nation’s primary goals of economic growth

and employment.

In the 1970s, Dr Goh Keng Swee, then Deputy Prime Minister and architect behind Singapore’s economic

development, stressed that “the government as policy-maker should distance itself from its role as

shareholder in these companies [GLCs]”.2 Thus, Temasek was established in 1974 to hold investments in

companies previously held directly by the Minister for Finance (Incorporated), which became its sole

shareholder. With Temasek owning these GLCs, the government could focus on its core economic roles

of policy-making and market regulation.

In Singapore’s public administration, government ministries are supported by statutory boards that are

“public institutions created through legislation” and given “relatively more freedom to employ the

necessary human expertise and use financial resources to implement projects and programmes than their

parent ministries.”3 For example, the Ministry of Transport oversees the “development and regulation of

civil aviation and air transport, maritime transport and ports, and land transport”. 4 One of its statutory

boards, the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore (CAAS) is tasked with regulatory functions in civil

aviation safety and security, air services, airports and aerospace industries; as well as licensing in the

provision of air services, the operation of airports and the provision of airport services and facilities in

Singapore. Singapore’s Changi Airport is managed by Changi Airport Group (Singapore) Pte Ltd, which

undertakes functions in airport operations and management, air hub development, commercial activities

and airport emergency services. Changi Airport Group is a wholly-owned private company of the Ministry

of Finance (GLC), while the national airline Singapore Airlines is a GLC majority-owned by Temasek

Holdings. So, in Singapore’s air transport arena, the ministry takes on the role of policy-maker, the

statutory board is the regulator and licence-granting agency, one GLC takes on airport operations and

management, and a Temasek portfolio company provides air transport to civilians, albeit in competition

with more than 80 other airlines serving Singapore.

TEMASEK’S BACKGROUND AND BOARD

“As with any private enterprise, if you do a major move, you will speak to your major

shareholders – it happens in the private sector. Obviously, we don't keep secrets from the

Government on major moves we want to make, we keep them informed. But basically at the end

of the day, the board and management of Temasek are responsible for the performance of

Temasek.”5

S. Dhanabalan, Chairman of Temasek, 2013

Temasek is an exempt private company and is not legally required to publicly disclose its financial results.

As a commercial investment company, Temasek is under the purview of the Singapore Companies Act

1

Temasek Holdings. (2002). Background and context of Temasek Charter 2002.

2

The architect of Singapore's prosperity. (2010, May 15). Straits Times Singapore.

3

Neo, B. S., & Chen, G. (2007). Dynamic governance: Embedding culture, capabilities and change in Singapore.

Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, p. 411.

4

Ministry of Transportation website http://www.mot.gov.sg/

5

Transcript: Remarks by Chairman of Temasek, Mr S Dhanabalan, to Singapore media, 23 July 2013.

Retrieved November 16, 2015 from http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/newsreleases?detailid=19992

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 3

ABCC-2016-001

and other laws and regulations, with its business and policies guided by a board of directors, majority of

whom are non-executive independent business leaders from the private sector.

The Temasek board is responsible for decision-making on matters pertaining to overall long-term

strategic objectives, annual budget, annual audited statutory accounts, major investment and divestment

proposals, major funding proposals, CEO appointment and succession planning, and changes to the

board. In addition, the board and CEO have the constitutional responsibility of protecting Temasek’s past

reserves6, and approval from the President of Singapore has to be obtained before Temasek could draw

on its reserves.

Between 1974 and 1986, Temasek’s board chairman was J. Y. Pillay, who was then Permanent

Secretary (Revenue Division) for Ministry of Finance. During this period, Pillay also held a number of

concurrent appointments including Chairman of Development Bank of Singapore Ltd 7 (1979-1985),

Chairman of Singapore Airlines Ltd (1972-1996), and Managing Director of Monetary Authority of

Singapore and Government of Singapore Investment Corporation 8 (1985-1989). In fact, Pillay is best

remembered as the aviation veteran who built Singapore Airlines (SIA) into a world-class airline.

In January 1987, Pillay was succeeded as Chairman of Temasek by Lee Ek Tieng, who was then

Permanent Secretary (Revenue Division) for Ministry of Finance (1986-1989). During the years when Lee

was Chairman of Temasek (1987-1996), he was also the Permanent Secretary (Special Duties) in the

Prime Minister’s Office (1994-1999), Managing Director of Monetary Authority of Singapore (1989-1997)

and Managing Director of Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (1989-2007).

In 1996, S. Dhanabalan was appointed as Chairman of Temasek. Unlike his two predecessors who were

high-ranking civil servants at Ministry of Finance at the time of their appointments, Dhanabalan was a

retired politician and former Cabinet Minister. From 1981 to 2005, he was also a Director of Government

of Singapore Investment Corporation. During his 17-year tenure at Temasek, Dhanabalan also held

concurrent appointments as Chairman of SIA (1996-1998) and Chairman of DBS Group Holdings (1999-

2005). As Chairman of Temasek, he was credited for the company undertaking a “proactive shareholder

role in driving the governance of its companies” 9 and the Temasek portfolio expanding from S$70 billion

to S$215 billion over a 16-year period. 10 Dhanabalan appointed Ho Ching as Temasek’s Executive

Director in 2002 and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) in 2004. Ho, the spouse of Lee Hsien Loong,

Singapore’s Prime Minister since 2004, is the former CEO of Singapore Technologies, a Temasek

portfolio company prior to joining the Temasek board.

In 2013, following Dhanabalan’s retirement from Temasek days before his 76 th birthday, 65-year-old Lim

Boon Heng became the fourth Chairman. Lim is a retired politician, former Cabinet Minister

(Dhanabalan’s ex-colleague) and ex-union leader. While Lim did not have a background in banking and

finance, he had amassed business experience from his time as a senior executive of Neptune Orient Line,

and from overseeing cooperatives that were under the umbrella of Singapore’s National Trades Union

Congress.

“Because of the early years of history, the first 15 years or so of being very closely connected

with the Government, the key decisions were made in close consultation with the Government,

6

Temasek’s past reserves are defined as its total assets minus liabilities (reserves) accumulated during previous

terms of Government.

7

Development Bank of Singapore and Singapore Airlines were two of the 35 companies in Temasek’s portfolio in

1974. The former later became part of DBS Group Holdings Ltd.

8

Government of Singapore Investment Corporation was renamed GIC Private Limited. It was formed in 1981 to

manage Singapore’s foreign reserves.

9

Keynote speech by S. Dhanabalan, Chairman, at the Asian Business Dialogue on Corporate Governance 2002.

31 October 2002. Retrieved November 16, 2015 from

http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/speeches?detailid=8629

10

Statement on Temasek Holdings Chairman succession. (2013, July 22). Today (Singapore).

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 4

ABCC-2016-001

including the appointment of the chairman, the appointment of directors, the appointment of the

CEO. In fact before Ho Ching, all the CEOs were civil servants.”11

S. Dhanabalan, Chairman of Temasek, 2013

“[Afternote to quote: the Temasek CEO before Ho Ching was another senior executive from the

Singapore Technologies group, not a civil servant; the General Managers or Presidents before that were

civil servants seconded to Temasek.]”12

TEMASEK CHARTER

In 2002, after Ho Ching was appointed Executive Director, one of her immediate tasks was to draw up the

Temasek Charter, in consultation with the Ministry of Finance. The Charter described Temasek’s mission,

role and responsibilities, as well as outlined its long-term investment approach given that portfolio

diversification was in the pipeline. As Temasek began to set its sights on Asia and beyond, the Charter

summed up “how Temasek would work with its portfolio companies to ensure financial discipline and

sound governance in building significant international or regional businesses.” 13

In July 2002, the first version of the Charter was released (see Exhibit 1A). The key points of the

Charter’s background and context (see Exhibit 1B) were as follows:

Temasek would focus on developing internationally competitive companies.

The government would continue to own and control companies for strategic reasons revolving around

national security, economic development and social policies. Temasek would uphold its stewardship

of these GLCs.

The GLCs could partner other companies or shareholders in their overseas ventures. Temasek could

provide support to these GLCs “through the issuance of new shares, or mergers or acquisitions”.

Temasek might make selective investments in “new businesses with regional or international potential

in order to nurture new industry clusters” that could involve “high risk, large investments or long

gestation periods”.

Temasek would “continue to rationalise and consolidate its shareholdings” in order to enhance the

shareholder returns. Temasek would “continue to divest companies that no longer required

government control” or companies with little potential in regionalization or globalization.

In 2009, the Temasek Charter was updated and released in conjunction with Temasek’s 35 th anniversary

(see Exhibits 2A and 2B). The 2009 Charter highlighted Temasek’s commitment towards corporate

social responsibility and the wider community, but it contained no reference to Singapore or the

government. Two years earlier, Temasek had set up Temasek Trust, its philanthropic arm, to “oversee the

financial management and disbursement of Temasek’s philanthropic endowments and gifts.” 14 Since then,

Temasek began to place more emphasis on its community stewardship role, as demonstrated by its

Charter.

11

Transcript: Remarks by Chairman of Temasek, Mr S Dhanabalan, to Singapore media, 23 July 2013. Retrieved

November 16, 2015 from http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/newsreleases?detailid=19992

12

ibid.

13

Temasek Charter reiterates Temasek’s focus on long-term value: Temasek updates Charter on its 35th

anniversary. (2009, August 25). Temasek news release.

14

Temasek Holdings. (2015). Temasek Review 2015.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 5

ABCC-2016-001

Since 2012, the Charter had emphasized Temasek’s three key roles of “active investor and shareholder”,

“forward-looking institution” and “trusted steward” (see Exhibits 3 and 4). As a ‘work-in-progress’, the

Charter would be revised again in the future to keep up with the times.

PRIVATIZATION OF STATUTORY BOARDS

In 1985, Singapore was facing an economic recession and its government decided to embark on a

privatization strategy as a means of restructuring the economy. Three objectives for the privatization were

given: “to withdraw from commercial activities that no longer need to be undertaken by the public sector;

to add breadth and depth to the Singapore stock market by the floatation of GLCs and the statutory

boards and through the secondary distribution of government-owned shares; and to avoid or reduce

competition with the private sector.”15

In February 1986, the newly-formed Public Sector Divestment Committee headed by Michael Fam, then

chairman of Fraser and Neave, was appointed to identify GLCs that should be privatized. A year later, the

Public Sector Divestment Committee released a report that listed 41 GLCs that should be privatized over

the next decade. The Committee also recommended that further research on the privatization of four

statutory boards be carried out. These four statutory boards were Singapore Telecom, Public Utilities

Board, Port of Singapore Authority, and Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore. Out of the 41 GLCs, 27

were owned by Temasek while statutory boards and ministries owned the remaining. The types of

privatization put forth included public listing, complete divestment and reduced government shareholding.

In June 1989, Coopers and Lybrand, which had been commissioned to conduct a feasibility study on the

privatization of Singapore Telecom, submitted a report to the Ministry of Communications and Information.

The findings of the report recommended that Singapore Telecom, the statutory board housing the

telecommunications and postal departments, be privatized. Between 1986 and 1989, Singapore Telecom

had registered double-digit growth in its annual net revenue, which strengthened its candidacy as the first

statutory board to undergo privatization.

In 1992, the Telecommunication Authority of Singapore, a statutory board under the Ministry of

Communications was formed and became the new regulator of Singapore’s telecommunications and

postal industries. The old Singapore Telecom was corporatized 16 and became a wholly-owned subsidiary

of MinCom Holdings Private Limited (MinCom), a newly-formed holding company under Ministry of

Communications.

In the first half of 1993, ownership of Singapore Telecommunications Private Limited (“SingTel”) was

transferred from MinCom to Temasek. In October 1993, 11% of total shareholding of SingTel was publicly

listed on the Stock Exchange of Singapore while 89% was held by Temasek. 17 In later years, Temasek’s

stake in SingTel was progressively reduced through share placements.

On 1 October 1995, the corporatization of Public Utilities Board (PUB) spun off two new companies,

Singapore Power Pte Ltd and Tuas Power Pte Ltd, while PUB remained as the regulatory body for

electricity and gas provision, and the statutory board responsible for the nation’s water supply. Both

Singapore Power and Tuas Power were wholly-owned subsidiaries of Temasek. Singapore Power

became the holding company of five independent subsidiaries: two electricity (power) generation

companies, PowerGen (Senoko) Pte Ltd (“Senoko”) and PowerGen (Seraya) Pte Ltd (“Seraya”), one

15

It pays to keep GLC shares: Study. (1993, March 26). Straits Times Singapore.

16

When an organization is corporatised, it remains government-owned but it has the flexibility to implement private

sector practices such as offering more competitive remuneration and better career advancement to its employees.

17

SingTel share history. Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://info.singtel.com/about-us/investor-

relations/singtel-share-history

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 6

ABCC-2016-001

electricity transmission and distribution company, an electricity supply company and a gas company.

Tuas Power took charge of the construction and operations of the upcoming Tuas power plant.

Initially, Singapore Power was scheduled to be publicly listed in mid-1996; but the plan was later

indefinitely shelved. Instead, the government announced in 1999 that the three electricity (power)

generation companies (gencos), Tuas Power, Senoko and Seraya would be divested at an opportune

time. In 2001, ahead of the divestment, the ownership of Senoko and Seraya was transferred from

Singapore Power to Temasek, with Singapore Power retaining its power grid and power supply business.

In 2008, all three gencos were successfully divested by Temasek (details in a later section).

On 1 October 1997, two years after the corporatization of PUB, the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA)

became the third statutory board to be corporatized and was renamed PSA Corporation Limited. A year

earlier, a new statutory board, the Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA) had been formed to

take over the regulatory functions of the PSA. PSA Corporation continued to be the operator of container

terminals in Singapore. In 2002, Temasek announced that the shares of PSA Corporation would not be

publicly listed in the immediate future. In December 2003, PSA International Private Limited, a wholly-

owned subsidiary of Temasek, was incorporated as the main holding company for the PSA Group, to

reflect PSA’s internationalization focus. In 2015, PSA International was still wholly owned by Temasek.

On 1 July 2009, nearly 12 years after the corporatization of PSA, Singapore Changi Airport was

corporatized. The timing had been delayed by market uncertainties that arose from unforeseen events

such as the Asian financial crisis, 9/11 terrorist attacks and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

outbreak. Changi Airport Group (Singapore) Pte Ltd (CAG), which was incorporated on 16 June 2009,

became the new operator of Changi Airport and also took charge of the government’s investments in

overseas airports. The restructured Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore would continue with its regulatory

functions in air traffic services, air services negotiations, safety and customer service. The corporatization

would provide the new company with “more flexibility to innovate, to be responsive and to be nimble to

changing industry conditions and new competitive challenges”. 18 While it was announced as early as

2009 that CAG’s ownership would be transferred from Ministry of Finance to Temasek, this had yet to

take place at the time of writing. One given explanation was that the construction of Changi Airport’s

Terminal Four and Jewel (a new retail and entertainment extension), and the expansion of Terminal One

required huge financial outlays and hence, the transfer was postponed.

THE “CUSTODIAN” YEARS (1974-2002)

Since its inception in 1974, Temasek has been wholly owned by the Minister for Finance (Incorporated).

Temasek’s initial portfolio comprised 35 GLCs that had a combined valuation of S$354 million (see

Exhibit 5). These GLCs were in industries that were critical to Singapore’s economic growth – banking,

aviation, shipping, shipbuilding and defence technology.

“For many years Temasek continued in that mode [of owning the companies], making some

small investments, basically looking after the companies it had inherited.”19

S. Dhanabalan, Chairman of Temasek, 2013

In the 1980s, Temasek had started to reduce its stakes in GLCs that “could stand on their own and were

no longer of national or strategic importance”.20 Companies such as Ethylene Glycols, a manufacturer of

18

Corporatised airport still soaring high. (2015, July 1). Straits Times Singapore.

19

Transcript: Remarks by Chairman of Temasek, Mr S Dhanabalan, to Singapore media, 23 July 2013. Retrieved

November 16, 2015, from http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/newsreleases?detailid=19992

20

Temasek cannot divest stakes in GLCs overnight. (2000, May 4). Retrieved November 16, 2015, from

http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/medialetters?detailid=10656

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 7

ABCC-2016-001

chemicals, Cerebos Singapore, a manufacturer of chicken essence, and Mitsubishi Singapore Heavy

Industries were fully divested. For Temasek, investment and divestment decisions were exercised based

on value tests and long-term returns. Like any investment holding company, Temasek acquired stakes in

companies that it expected to generate positive returns on investment, be they GLCs, private companies

operating in or outside Singapore, or start-ups. Temasek had exited from companies that were

underperforming or could not be turned around, such as Construction Technology (sold at a loss in 1996)

and Micropolis (liquidated in 1997).

Over a period of 28 years, Temasek had divested approximately 70 or so companies, either completely or

partially.21 Then, there were companies in Temasek’s portfolio that had increased exponentially in their

market capitalization. For example, DBS was valued at S$49 million in 1975; in 2002, Temasek’s

shareholding in DBS was valued at S$2.3 billion. Another example was SIA. In 1975, SIA was valued at

S$91 million; in 2002, Temasek’s shareholding in SIA was valued at S$8.2 billion. 22

In 1990, Temasek established an in-house fund management unit and began to invest in private equity

funds. In the 1990s, two former statutory boards, Singapore Telecom and PUB were corporatized and

transferred to Temasek.

For the financial year ended 31 March 2002, Temasek’s portfolio was S$77 billion compared with S$354

million in 1974. Its consolidated group revenue was S$42.6 billion and net profit was S$4.9 billion. Its

return on average assets was 5.1% while its return on average equity was 9.2%.

From 1974 to 2004, Temasek’s total shareholder’s return (TSR) by market value averaged 18% per

annum. However, over the 10-year period from 1994 to 2004, which was marked by the Asian financial

crisis, global economic downturn, 9/11 terrorist attacks and the SARS outbreak, Temasek’s TSR only

averaged 3% per annum.

“There were some attempts to invest, especially during the Asian financial crisis, but not in a

great concerted way. It was only from 2002 onwards that Temasek began to really seek to

invest outside Singapore. First of all we decided to focus on an emerging Asia because we

could see that rapid growth in Asia – China, India, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and so on. And

then we began to look at other emerging markets like those in Latin America.”23

S. Dhanabalan, Chairman of Temasek, 2013

THE “ACTIVE INVESTOR” YEARS (2002-2015)

“We want [Temasek-linked] companies to focus on their core competencies. If they cannot grow,

they will be the lunch themselves”24

Ho Ching, Executive Director, 2002

For years, there had been grouses from local small and medium-sized companies about GLCs competing

with them in the small, overcrowded domestic market. GLCs were also diversifying into unrelated but

profitable local businesses such as property development and food retail. Thus, an imperative task for

Temasek was to steer its GLCs into developing core competencies or new technologies that enabled

them to expand into new overseas markets.

21

Temasek Holdings. (2004). Temasek Review 2004, p. 11.

22

It's S'pore Inc against the world. (2002, August 29). Business Times Singapore.

23

Transcript: Remarks by Chairman of Temasek, Mr S Dhanabalan, to Singapore media, 23 July 2013. Retrieved

November 16, 2015 from http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/newsreleases?detailid=19992

24

Temasek Charter. (2002, July 4). Business Times Singapore.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 8

ABCC-2016-001

Between 2002 and 2004, Temasek divested its shareholding in 36 companies including Natsteel, CPG

Corporation Pte Ltd, Changi International Airport Services Pte Ltd and Singapore Pools. In the same

period, Temasek invested S$3.3 billion in 35 companies including Hyflux, Cosco Corporation, Olam

International and YHI International in Singapore; US-based Quintiles; banks in Indonesia, India and Korea;

and Matrix Laboratories, Tata Consultancy Services and ICICI OneSource in India. Temasek’s long-term

investment goal was to reshape its “portfolio with one-third of [its] asset exposure in Singapore, one-third

in the developed economies (including US, Canada, Europe, Japan and Australia), and the remaining

one-third in the rest of Asia”. 25 Tasked with managing Temasek’s capital resources, a wholly-owned

subsidiary, Fullerton Fund Management Company was set up.

In 2004, Temasek began to publicly disclose its financial results in its annual Temasek Review so as to

provide more transparency in its investment activities. It also received a corporate credit rating of

AAA/Aaa by Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s, respectively. In 2005, Temasek issued its first bond, which

was denominated in US dollars and targeted at investors worldwide.

In 2006, a Temasek-led consortium acquired a 49.6% controlling stake in Thailand's Shin Corp from the

family of then Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra. The acquisition created a backlash in Thailand.

For starters, the sale had given the Shinawatra family a 73-billion-baht (S$3.03 billion) “tax-free windfall”26.

Then, the amendment of Thailand’s Telecommunication Operation Act, which raised the cap of foreign

ownership in Thai telecoms companies from 25% to 49%, had become effective on the same day as the

Shin Corp sale. Finally, one Thai senator had criticized the sale as “tantamount to selling off radio

frequencies that were the national assets to foreigners”.27

In November 2007, Temasek was mired in another controversy. Temasek was fined by Indonesia’s

Business Competition Supervisory Commission (KPPU) for violating anti-monopoly law because of its

cross-ownership in Indonesia’s two largest telecommunications companies, PT Telekomunikasi Selular

(Telkomsel) and PT Indosat. Temasek then had a 56-percent shareholding in SingTel, which in turn, had

a 35-percent stake in Telkomsel. ST Telemedia, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Temasek, owned 39.96

percent of Indosat. Temasek had a deemed 20-percent stake in Telkomsel and a deemed 31-percent

stake in Indosat.28 Temasek, which denied violating the law, filed appeals against KPPU’s ruling but was

rejected by the Indonesian courts. In June 2008, ST Telemedia sold its stake in Indosat to Qatar Telecom.

In 2008, Temasek was adversely impacted by the global economic crisis. Its portfolio market value shrank

from S$185 billion to S$130 billion as one-third of its portfolio was invested in the financial services sector.

A year later, Temasek’s portfolio market value recovered to S$186 billion following a recalibration of its

investment and divestment strategies.

In March 2015, Temasek's portfolio was valued at S$266 billion, up from S$103 billion a decade ago (see

Exhibit 6). The portfolio had 28% asset exposure in Singapore, 42% exposure in Asia (excluding

Singapore) and 30% exposure in the rest of the world. Temasek’s investments were diversified across

varied industry sectors (including financial services, telecommunications, technologies, transportation,

real estate, energy, and life sciences). Exhibits 7 and 8 show how Temasek’s portfolio had changed in its

industrial and geographical exposure at five-year marks from 2004 until 2014.

“Temasek is a long-term investor. As I had outlined five years ago, this means we will act to

enhance long-term value, and will not divest for divestment’s sake. We don’t intend to raid the

larder, nor sell the family jewels, for short-term gains. We will jealously guard our interests, and

25

Temasek Holdings. (2005). Temasek Review 2005, p. 10.

26

Thai premier calls new election but refuses to step down. (2006, February 25). New York Times.

27

PM: Shin sale my kids' idea; Says he'll avoid conflict of interest charges in 73-billion-baht, tax-free sell-off to

Singapore's Temasek. (2006, January 24). Bangkok Post.

28

Temasek’s anti-trust appeal nixed. (2008, September 12). Today (Singapore).

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 9

ABCC-2016-001

will invest, rationalise, consolidate or divest where it makes sense, and where we can achieve

clear sustainable value.”29

Ho Ching, Executive Director and CEO, 2009

TEMASEK’S APPROACH TO CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

“A sound framework of governance founded on integrity, professional management and

commercial discipline has been and will continue to be the cornerstone for the growth and

success of Temasek and its portfolio companies.”

Background and Context of Temasek Charter 2009

The following figure highlights Temasek’s approach to governance and value creation.

Source: Temasek Review 2009

In Temasek’s view, a corporate governance framework would encompass “principles of appropriate

transparency, checks-and-balances, sensible reward systems and a professional and objective

management” in order to attain “a pragmatic balance between accountability, empowerment and

organizational agility”. 30 The philosophy of Temasek was that its portfolio companies’ decision-making

process had to demonstrate transparency and accountability, which were brought about by

institutionalizing good corporate governance practices, and not through its own participation in the

management of the entities.

In his speech about corporate governance, Dhanabalan, Chairman of Temasek (1996-2013) underscored

the “paramount emphasis” that Temasek placed on the “character, values and competence of the people

who lead the company at Board and management level” as “the most important requirements for the

29

Speech by Ho Ching, Executive Director & CEO, at the Institute of Policy Studies, Singapore, 29 July 2009.

Retrieved November 16, 2015, from http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/speeches?detailid=8600

30

Temasek Holdings. (2004). Temasek Review 2004, p. 34.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 10

ABCC-2016-001

success of a company”.31 Temasek believed that a high-quality board and management team were sine

qua non in supporting sound corporate governance; hence, a formal succession planning process for

their boards and management had to be in place.

“Where GLCs are not doing well, the management has to sort out the problems. If necessary,

the board may need to make management changes, or the shareholders including Temasek

may need to make board changes.”32

Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Lee Hsien Loong, 2002

Over the years, Temasek had reiterated publicly that it was not involved in its portfolio companies’

commercial or operational decision-making, except where shareholder approval was required. The

portfolio companies had their individual management teams and boards of directors to run their business

on a commercial basis.

“We cannot forbid a listed company from doing certain activities, just because the government

happens to own shares in it. It is wrong both legally, and also from a policy point of view. GLCs,

especially listed GLCs, must operate commercially. That doesn't mean DBS should go into

manufacturing chips, or PSA should start an airline business. The decisions must make

business sense, and fit the companies' business strategy.”33

Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Lee Hsien Loong, 2002

Temasek was known to hold stakes in rival companies operating in the same industries (e.g., Keppel

Corporation vs. SembCorp Industries; DBS Group Holdings Ltd. vs. Standard Chartered PLC). Hence, it

was keen to steer clear of any controversy of unfair competition. However, this never deterred Temasek

from creating opportunities for the sharing of non-sensitive and non-privileged knowledge and information

(e.g., risk management issues, internal audit issues, board directors’ remuneration) among its investee

companies.

As an institutional shareholder, Temasek sought to add value to its portfolio companies by undertaking a

“proactive stewardship role” in the following areas:

nomination of capable and high-quality Board candidates;

performance-based compensation schemes for employees including stock options;

approval of material transactions such as mergers and acquisitions; and

institutionalizing of corporate governance practices.34

Temasek’s management staff rarely appeared on the boards of its portfolio companies and when they did,

they were appointed in their own individual capacity. (In 2004, the former made up 7% of the directorships

on the boards of 34 major Temasek-linked companies. In 2005 and 2006, this figure stood at 4%. This

figure was absent in subsequent Temasek Review publications.) Instead, the company expended

considerable effort into developing a good network of “people who are successful, who have interests in

31

Keynote speech by S. Dhanabalan, Chairman, at the Asian Business Dialogue on Corporate Governance 2002.

31 October 2002. Retrieved November 16, 2015, from

http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/speeches?detailid=8629

32

It's S'pore Inc against the world. (2002, August 29). Business Times Singapore.

33

ibid.

34

Keynote speech by S. Dhanabalan, Chairman, at the Asian Business Dialogue on Corporate Governance 2002.

31 October 2002. Retrieved November 16, 2015, from

http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/speeches?detailid=8629

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 11

ABCC-2016-001

this part of the world [Asia], who are friendly to Singapore, who can form the pool from which we can draw

directors for Temasek as well as for Temasek[-linked] companies”.35

Starting in 1999, two years after the Asian financial crisis, Temasek had advocated a number of changes

aimed at improving the governance of Temasek-linked companies (defined as companies where it held at

least a 20-percent stake). These changes were:

separating the roles and responsibilities of Chairman and CEO;36

limiting the tenure of the Chairman and Board of directors to two terms (or six years) or in exceptional

circumstances, a maximum of three terms (or nine years);

limiting each Board director to hold a maximum of six principal directorship; and

implementing new performance benchmarks such as economic value added (EVA).37

In later years, the company also advocated that “the Chairman and CEO roles be held by separate

persons, independent of each other, to ensure an appropriate balance of power and greater capacity of

the board for independent decision making”38 and that “boards be independent of management in order to

provide effective oversight and supervision of management”. 39 The company was also against “excessive

numbers of executive members on company boards”.40

As Temasek diversified its investments outside of Singapore, it was guided by the Temasek Charter. To

demystify its businesses and operations, Temasek began to release its annual report (Temasek Review)

to the public from 2004 onwards. The company’s rationale was that with the globalization of its

investments and growth in partnerships with international co-investors, demonstrating greater disclosure

and transparency in its financials, goals and activities would be beneficial.

HOW TEMASEK CREATED VALUE – EXAMPLE OF POWER GENERATION COMPANIES

(1999-2008)

Besides being an investor and a shareholder, Temasek had also contributed to Singapore’s economic

growth as an asset owner whereby it nurtured the growth of newly privatized GLCs before taking them

public or divesting them for profits. One notable example was the power generation companies (gencos).

In 1999, Temasek was mulling over the divestment of Tuas, which was formed in March 1995. The plan

was later shelved because market sentiment was weak and the government had decided to restructure

the power generation market. Temasek worked closely with the Singapore regulators and government

authorities “to ensure an orderly transition to a stable and competitive power generation market in

Singapore.”41 In 2001, Singapore Power’s two gencos, Seraya and Senoko were sold to Temasek for

S$2.818 billion42 and Temasek became the direct owner of all three gencos – Seraya, Senoko and Tuas.

35

Transcript: Remarks by Chairman of Temasek, Mr S Dhanabalan, to Singapore media, 23 July 2013. Retrieved

November 16, 2015, from http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/newsreleases?detailid=19992

36

In 1999, Keppel Corporation, PSA Corporation, and their subsidiaries were the only Temasek-linked companies

that had yet to separate the Chairman and CEO functions.

37

Temasek fine-tunes stewardship of its companies. (1999, June 25). Business Times Singapore.

38

Temasek Holdings. (2012). Temasek Review 2012, p. 46.

39

Temasek Holdings. (2013). Temasek Review 2013, p. 54.

40

Temasek Holdings. (2012). Temasek Review 2012, p. 46.

41

Temasek successfully completes divestment of Tuas Power; Power genco sold to China Huaneng Group for

S$4.235 billion. (2008, March 14). ENP Newswire.

42

Interview: Singapore SembCorp seeks 12% ROE in power company bid. (2002, February 20). Dow Jones Energy

Service.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 12

ABCC-2016-001

Singapore Power remained in the business of electricity distribution and supply, but not in the electricity

(power) generation business.

In April 2001, the Energy Market Authority (EMA), a statutory board under the Ministry of Trade and

Industry, was formed with the regulatory function of Singapore’s electricity and gas markets including

overseeing their liberalization. In January 2003, the National Electricity Market of Singapore (NEMS), a

competitive wholesale electricity market, became operational. The NEMS ran a trading platform for the

purchase and sale of electricity, which heated up competition among the gencos. In January 2004,

vesting contracts were introduced as a replacement of price caps for the three Temasek-owned gencos;

although new licensees were exempted from the vesting. A vesting contract requires a genco to sell a

given quantity of electricity at a given price, which in turn, helps to guard prices against fluctuations.

One key phase of the electricity market liberalization concerned the sale of the three Temasek gencos,

which were the dominant players in power generation.43 In 2002, Temasek had announced that 2004 was

the earliest that the gencos would be put up for sale because of challenging market conditions following

the Enron collapse. However, three months after vesting contracts had been introduced, electricity prices

decreased from S$92.64 per megawatt-hour to S$83.74 per megawatt-hour. The gencos were also hit by

challenges posed by market overcapacity and stagnant market demand (the three gencos produced a

total of more than 9,000 megawatts of electricity while peak demand was about 5,100 megawatts).

Before the year 2003 drew to an end, press announcements about the impending retirement of Shum

Siew Keong, Managing Director of Seraya, and Lau Khoon Choy, President and Chief Executive Officer

of Senoko, were made. Shum was succeeded by 48-year-old Neil McGregor who “had more than twenty

years of management experience in the international power, gas and deregulated electricity industry

environment”.44 Lau’s successor was Roy Adair who had “the requisite experience of operating in the

competitive electricity environment” in both the U.K. and Australia.45

In February 2004, Seraya retrenched 110 (25 percent) of its employees, who received the severance

package in accordance to the collective agreement between the Union of Power and Gas Employees

(UPAGE) and the company. Seraya also entrusted UPAGE with the disbursement of S$300,000 in

‘Economic Assistance Payments’ to the company’s retrenched union members, with each individual

collecting between S$2,600 and S$5,000.46 Six months later, a downsizing exercise also took place at

Senoko and led to the departure of 126 employees (28 percent of staff). The retrenched employees

received the severance package agreed between UPAGE and Senoko.47

In 2005, the media reported that Temasek had been conducting a review of the electricity market to

assess the interest of investors in its gencos.48 In early 2006, Temasek announced that it would divest its

three gencos after the government’s implementation of the gas code. While Senoko depended on

Malaysian and Indonesian piped gas as its main fuel, both Seraya and Tuas relied on Indonesia-imported

gas. Hence, having an open-access, integrated gas system where gas from different sources would be

mixed in one grid, would help improve supply security and level the playing field of gencos and gas

suppliers.

In mid-2007, Temasek confirmed that the sale of its three gencos was underway and was expected to be

completed by mid-2009. According to Wong Kim Yin, Temasek's managing director of investments, the

gencos had attracted much interest from potential investors since 2006; although he did not reveal the

identities of the interested parties.49 Wong also pointed out that “conditions are conducive for divestment”

43

More power to liberalisation. (2003, January 4). Business Times Singapore.

44

Our Page: A newsletter of the Union of Power and Gas Employees. January 2004, p. 5.

45

Our Page: A newsletter of the Union of Power and Gas Employees. January 2004, p. 6.

46

Our Page: A newsletter of the Union of Power and Gas Employees. June 2004, p. 8-9.

47

Our Page: A newsletter of the Union of Power and Gas Employees. November 2004, p. 8.

48

Temasek seen reviewing power market. (2005, January 13). Business Times Singapore.

49

Long-awaited genco sale finally takes off. (2007, June 20). Business Times Singapore.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 13

ABCC-2016-001

given the strong economic growth forecasts of Singapore and that “the regulatory framework governing

the competitive wholesale supply of gas and power is also complete.” 50 The gencos would be divested

one at a time, with no limit placed on foreign ownership. The Ministry of Trade and Industry had

rationalized that foreign ownership of gencos would not pose a problem to energy security as “foreign

owners will not be able to walk away with their power plants”.51

In October 2007, Tuas was the first Temasek genco to be put for sale as it had attracted “the strongest

investor interest”.52 Among the three gencos, Tuas was the smallest but the most profitable. Its revenue

and earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) for the year ended March 2007

was S$2.267 billion and S$331 million, respectively. Tuas also had the newest power plant in Singapore.

With an installed capacity of 2,670 megawatts, Tuas had a 26% share of the local electricity market. By

contrast, in 1999, Tuas was just a new genco starting out and running at a loss. If it had been sold then, it

was unlikely to have fetched more than S$2 billion, which was its market-estimated price tag in 2007.

Preparation for the Tuas divestment had taken Wong Kim Yin, Temasek's managing director of

investments and his team 18 months of hard work. The Tuas sale was important as it would set a price

benchmark for the subsequent sales of the two remaining gencos. The divestment process comprised

two stages and lasted around five months. In the first stage, information packs or Memoranda of

Information were given to potential investors who then submitted their indicative proposals to Temasek.

From these proposals, Temasek shortlisted a number of bidders for the second stage, which saw these

bidders making site visits, going through Tuas’ financials and management presentations, and conducting

their own due diligence. These bidders then submitted their binding offers and Temasek selected the

winning bid based on “integrity, transparency and price.”53

According to the media, six bidders were shortlisted for the second stage of the Tuas sale. On 14 March

2008, Temasek signed an agreement to sell 100 percent of Tuas to SinoSing Power Pte Ltd, a wholly-

owned subsidiary of China Huaneng Group for the cash consideration of S$4.235 billion. The sale was

completed on 24 March 2008.

According to Wong Kim Yin, “China Huaneng is an established player with a strong track record in the

power business. Its proposal through SinoSing was the most attractive. It emerged as the winner based

on clear considerations of price and acceptable commercial terms. We have no doubt that the future

growth and development of Tuas Power as an anchor power provider in Singapore will benefit from the

experience and resources that China Huaneng brings.” 54 China Huaneng was China’s largest power

generation company and had an installed generation capacity of over 71,000 megawatts. It also had a 50-

percent stake in OzGen, a genco in Australia. China Huaneng’s S$4.235-billion purchase was a

testament of the company’s confidence in Tuas’s growth potential.55

In July 2008, Senoko, the biggest among the three gencos, was put up for sale. With an installed capacity

of 3,300 megawatts, Senoko had a 30-percent share of the local electricity market. Its revenue and

EBITDA for the year ended March 2008 was S$2.495 billion and S$245 million, respectively.

After the first stage of the divestment process, Temasek had shortlisted five bidders. Concerned that the

shortlisted bidders could encounter difficulty in arranging for bank financing due to the global credit

crunch, Temasek offered them the option of ‘staple financing’ or a pre-arranged financing package

through its two sale advisers, Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse. On 5 September 2008, Temasek sold

Senoko to the five-member Lion Power consortium formed by France’s GDF Suez and Japan’s Marubeni,

50

Long-awaited genco sale finally takes off. (2007, June 20). Business Times Singapore.

51

ibid.

52

Tuas Power is first Temasek genco to go on sale. (2007, October 19). Business Times Singapore.

53

ibid.

54

Temasek successfully completes divestment of Tuas Power; Power genco sold to China Huaneng Group for

S$4.235 billion. (2008, March 14). ENP Newswire.

55

China Huaneng snaps up Tuas Power for $4.2b. (2008, March 15). Business Times Singapore.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 14

ABCC-2016-001

Kansai Electric Power Company, Kyushu Electric and Japan Bank for International Cooperation. Besides

the cash consideration of S$3.65 billion, Lion Power also assumed Senoko’s net debt of S$323 million.

According to Gwendel Tung, Temasek's director of investment, “The Lion Power consortium partners are

all established industry players with strong track records in power investments globally. Lion Power's

proposal was the most attractive in terms of price and commercial terms among a field of highly reputable

investors.”56

In October 2008, Seraya, the last of the three gencos was put up for divestment. With an installed

capacity of 3,100 megawatts, Seraya had a 30-percent market share in power generation. Its revenue

and net profit after tax for the year ended March 2008 was S$2.79 billion and S$218 million, respectively.

Seraya was promoted as a “quality asset” by Temasek with references to its “strong cash flow”, “strategic

location in Singapore” and “able management.”57

The timing of the Seraya sale was an attempt to leverage on the strong investor sentiment from the

earlier two genco sales; before market conditions worsened from the global financial crisis. Temasek

again offered ‘staple financing’ to the three shortlisted bidders. However, on 25 November 2008,

Temasek stopped the Seraya tender process, which was originally scheduled to close on 2 December

2008 because of adverse market conditions.58 The market believed that investor interest in the Seraya

sale was weak and that indicative bids from the first stage were lower than what Temasek had expected.

On 3 December 2008, Temasek announced that Seraya had been sold to YTL for a cash consideration of

S$3.6 billion after Temasek accepted YTL’s unsolicited proposal. YTL also assumed Seraya’s net debt of

S$201 million. According to media reports, the managing director of YTL and his team had met up with

Temasek’s senior management over two days to negotiate and seal the Seraya deal. To help YTL finance

the acquisition, DBS Bank provided the company with S$2.25 billion in loan facilities. As the divestment of

Seraya drew to an end, Temasek’s Wong Kim Yin gave his concluding statement, “Temasek had fulfilled

its commitment to help develop a competitive power generation market in Singapore.”59

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

“The corporate governance crisis in Corporate America shows us that although its corporate

governance system generally functions well, it is not foolproof. In fact, no amount of legislation

or imposition of rules can prevent willful fraud or impropriety.”60

S. Dhanabalan, Chairman of Temasek, 2002

A 2014 study reported that in general, Singapore Exchange-listed Temasek-linked companies had better

corporate governance practices than their non-Temasek counterparts.61 This finding appeared to suggest

that Temasek’s efforts in the championing of corporate governance had paid off. However, Temasek’s

long-drawn quest was not without its challenges, as illustrated by the following cases.

56

Temasek sells Senoko Power to Japanese consortium; Power genco sold to Marubeni-led Lion Power consortium

for an enterprise value of about S$4.0 billion. (2008, September 9). ENP Newswire.

57

Temasek goes ahead with sale of PowerSeraya. (2008, October 8). Business Times Singapore.

58

Lights go out on PowerSeraya sale. (2008, November 26). Business Times Singapore.

59

YTL ups the ante to clinch PowerSeraya. (2008, December 3). Business Times Singapore.

60

Keynote Speech by S Dhanabalan, Chairman, at the Asian Business Dialogue on Corporate Governance 2002.

The Oriental, Singapore. 31 October 2002. Retrieved November 16, 2015, from

http://www.temasek.com.sg/mediacentre/speeches?detailid=8629

61

Sim, I., Thomsen, S., & Yeong, G. (2014). The state as shareholder: The case of Singapore. Singapore: Chartered

Institute of Management Accountants; Centre for Governance, Institutions and Organisations, NUS.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 15

ABCC-2016-001

SembCorp Logistics62

In 2003, accounting fraud was uncovered at the Indian subsidiary of SembCorp Logistics by the newly-

appointed deputy managing director, an accountant by training. The subsidiary’s revenues were

overstated by S$15.5 million for the financial period from 2000 to 2002 and by S$1.3 million for 2003.63 In

addition, S$3 million in expenses was wrongly classified under fixed assets. The subsidiary terminated

the errant employees and also considered taking legal action against them.

ST Marine, a division of Singapore Technologies (ST) Engineering 64

In the Standard & Poor’s inaugural Transparency and Disclosure Survey published in November 2001,

Singapore Technologies (ST) Engineering was rated as one of Singapore’s companies with the highest

level of corporate transparency and disclosure in Asia Pacific. ST Marine was a division of ST

Engineering. In 2011, a number of former and current high-ranking employees of ST Marine (including the

former group financial controller and two former presidents) were arrested on suspicions of graft and

accounting fraud. Investigations by Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) revealed

that between 2004 and 2008, these employees had paid a total of more than S$500,000 in bribes to ST

Marine’s customers in exchange for company contracts. Another employee was found to have made

fraudulent petty-cash claims of more than S$500,000.

Olam International Ltd.

Olam International Ltd. (Olam) was a Singapore Exchange-listed global supply chain manager and

processor of agricultural products and food ingredients. Temasek’s investment in Olam began with a

13.76% stake in 2009. In November 2012, Muddy Waters, a short-seller that made financial gains from

betting that a company’s share price would fall, had published a 133-page report that discredited Olam’s

accounting practices and acquisitions, business model and solvency. Muddy Waters had taken a short-

selling bet against Olam. Despite Olam’s rebuttal that it was not at risk of insolvency and it filing a

defamation suit against Muddy Waters and its founder in retaliation, the share prices of the embattled firm

plunged by 14% in a week.

In early December 2012, Olam announced that it would be selling US$750 million in bonds and US$500

million in warrants to shareholders in a deal backed by Temasek. Olam had also formed a subcommittee

comprising its non-executive Chairman, lead independent director and chairman of Olam’s audit and

compliance committee, as well as governance and nomination committee, and two independent directors

to conduct an internal review. In January 2013, Olam issued a public statement that its subcommittee had

found Muddy Waters’ accusations to "have no basis in fact and provide no reason for concern".65

The Olam-Muddy Waters’ fallout saw Temasek raising its stake from 16.3% to 23% over a period of four

months and becoming Olam’s biggest shareholder. In April 2013, Olam revealed its new strategy aimed

to “generate free cash flow more quickly, reduce its gearing and capital expenditure and make its

business less complex.”66 In May 2014, Temasek raised its stake in Olam to 58.5%. The substantial

financial injection by Temasek was expected to shield Olam from market volatility, boost market

confidence, as well as provide long-term support for its strategy and business model.

On 1 October 2014, Kwa Chong Seng, a former deputy chairman of Temasek Holdings (1997-2012) was

appointed as an independent non-executive director at Olam and on 31 October 2015, became Olam’s

non-executive chairman. Kwa was concurrently the chairman of the Boards of Neptune Orient Lines

(another Temasek-linked company), Singapore Technologies Engineering (another Temasek-linked

62

SembCorp Logistics was 31% owned by Temasek and held through SembCorp Industries in FY2004.

63

SembCorp set to sue auditors. (2003, October 2). Lloyd's List.

64

ST Engineering was 55% owned by Temasek in FY2004, the year the graft started.

65

Olam acts to clarify doubts. (2013, January 3). Business Times Singapore.

66

Temasek offer lifts Olam clear of Muddy Waters. (2014, March 17). Business Times Singapore.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 16

ABCC-2016-001

company) and Fullerton Fund Management Co. (a wholly-owned Temasek subsidiary). With Kwa’s

appointment, Olam’s stakeholders could expect higher standards of company corporate governance.

Standard Chartered PLC

In July 2006, Temasek purchased an 11.5% stake in Standard Chartered PLC (StanChart) from the

estate of the late Singapore tycoon Khoo Teck Puat. Temasek’s stake in the London-listed bank rose to

19% in less than two years and maintained at about 18% in the years thereafter. Since 2013, StanChart

had been mired in a difficult business downturn that had led to decreasing profits (see Table 1). As at

January 2015, the StanChart shares were trading at prices that were 25% lower than what Temasek paid

for in 2007.67

In the third quarter of 2012, StanChart was hit by a legal scandal that cost the bank US$340 million in

settlement. The U.S. regulators accused StanChart of flouting U.S. trade sanctions laws by concealing

transactions of Iranian customers – transactions that added up to US$250 billion. The scandal raised

concerns that StanChart’s corporate governance might not be as sound as what had been projected to

the shareholders.

In May 2012, Temasek, the largest StanChart shareholder had abstained from voting for the re-election of

some of the bank’s executive directors. According to sources that were familiar with the company,

Temasek had been pushing for more non-executive directors and fewer executive directors to be

appointed on StanChart’s board, and its abstention was meant to convey its displeasure with the bank. 68

In response, StanChart had publicly attributed Temasek’s abstention to “a misinterpretation of UK

corporate-governance requirements”.69 In May 2013, Temasek again abstained from voting for the re-

election of four executives to StanChart’s board, which left little doubt about its stand pertaining to

“excessive numbers of executive members on company boards”. 70 By December 2014, the number of

executive directors on the StanChart board had decreased to three (see Table 2), which demonstrated

some degree of success on the part of Temasek.

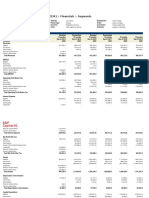

Table 1: StanChart’s Profit before Taxation (FY2006-2014)

Financial Year 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Profit before tax

3,178 4,035 4,568 5,151 6,122 6,753 6,851 6,064 4,235

(US$ mil)

Source: StanChart’s annual reports

Table 2: StanChart’s Board Composition (2008-2015)

Executive Directors Non-Executive Directors Chairman Total

Dec 2014 3 13 1 17

Jan 2013 6 14 1 21

Dec 2011 6 10 1 17

Dec 2010 5 10 1 16

Dec 2009 6 9 1 16

Dec 2008 4 8 1 13

Source: StanChart’s annual reports

67

Temasek should sit tight on troublesome stake in StanChart. (2015, January 1). Financial Times.

68

Singapore slings arrow at bank. (2012, October 3). The Wall Street Journal.

69

Global finance: Bank says Temasek misread U.K. Rules. (2012, October 5). The Wall Street Journal.

70

Temasek Holdings. (2012). Temasek Review 2012.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 17

ABCC-2016-001

In the cases of SembCorp Logistics and ST Marine, Temasek had chosen not to intervene and had given

the companies leeway to fulfil their responsibilities. Temasek had gone to the rescue of Olam plausibly

because Olam’s business fundamentals were sound and its balance sheet as at 30 June 2012 was its

“strongest” since the company’s IPO in 2005. 71 In the case of StanChart, Temasek had exercised its

shareholder rights through the AGM vehicle to improve governance. In the aforementioned examples, it

was noteworthy that Temasek had not interfered in the companies’ business operations in addressing the

governance issues.

CONCLUSION – THE UNIQUENESS OF TEMASEK

In a span of four decades, Temasek had seen its role evolve from custodian to active shareholder and

private equity investor, as the national economy underwent restructuring and transformation, and

globalization became the new reality. From the 1970s to the early 2000s, Temasek had contributed to

Singapore’s industrialization through its ownership and management of GLCs, as well as the

development of local enterprises through its financial investments. Beginning from the mid-1990s,

Temasek had worked with the government regulators to liberalize the telecommunication and power

generation markets, and privatize port operations, waste management and public housing development,

to name a few. In 2002, Temasek had turned to regionalization and internationalization as the main

strategy for enhancing the value of its assets including its GLCs. Since then, its stakeholder base had

widened beyond its sole shareholder (the government), to include investors of its bonds, partners,

investees and the wider community.

Temasek’s investments were financed using dividends and other cash distributions received from its

portfolio companies and other investments, divestment proceeds from sale of its investments, and the

occasional use of debt instruments such as Temasek-issued bonds. Temasek paid out dividends to its

sole shareholder, as well as contributed corporate taxes to the government’s revenue. So one relevant

issue was: how had Temasek’s sole shareholder, the Minister for Finance (Incorporated) evaluated its

past performance?

“The only reasonable way of evaluating Temasek's performance therefore, like that of any large

investor, is to look at how the losses and gains add up, and how its overall portfolio performs

over time. The facts are that Temasek has produced strong returns on its overall portfolio over

time – taking the investments that have done well with those that have turned bad; and taking

the boom years with the subsequent years when markets went bust. Temasek has in fact made

large investment gains over the course of the market cycle that began in 2003, including the

boom that lasted till 2007 as well as the subsequent bust.

Compared to any relevant market indices, or to other reputable institutional investors, Temasek

has performed respectably. Temasek has achieved total shareholder returns by market value of

slightly over 15% per year on average (in US dollar terms) over the cycle. This compares with a

6% annualised gain in the global equity market indices (MSCI World). A weighted index of

global, Asian and Singapore equity market indices would have delivered more than 6% but still

significantly less than Temasek’s gains of 15% per year. Temasek’s annualised returns are also

higher than what several other well-regarded investors have earned over the cycle. But while

Temasek has performed better than many other large investors over this six-year market cycle,

it is not realistic to expect it to outperform in every cycle. It is also not realistic to expect it to

avoid losses on every individual investment, or losses on its overall portfolio when the markets

go through sharp corrections.”72

Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Minister For Finance, 2009

71

Olam acts to clarify doubts. (2013, January 3). Business Times Singapore.

72

Speech by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Minister for Finance, 28 May 2009, 1:30 pm at Parliament.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 18

ABCC-2016-001

Temasek had stated publicly that “neither the President of the Republic of Singapore nor the Singapore

government, our shareholder, is involved in our investment, divestment or other business decisions,

except in relation to the protection of Temasek’s own past reserves.” 73 In fact, Temasek’s government

shareholder took a long-term view of Temasek’s investments and performance, which helped to cushion

the company against losses incurred in the short term or during market correction.

Temasek had been held up as the exemplar of a successful state-owned enterprise (SOE) in the mass

media as well as in scholarly literature. One research report lauded Temasek for “operating with a clear

business mandate and at arm’s length from the government.”74 One often-asked question was whether

the Temasek model could be replicated elsewhere, for example, in China, Vietnam or South Africa. After

all, the factors behind the Temasek success story were no secret (the Temasek Charter served as a good

reference guide). Among the factors cited were proper demarcation of the state’s role as

owner/shareholder and as policymaker/ regulator; compliance of laws and regulations in foreign markets

by both Temasek and its GLCs; adherence to high standards of corporate governance; and focus on

long-term sustainable value.75 In October 2015, Bloomberg News reported that the Beijing-based State-

owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission was studying Temasek as a model for China’s

SOE reform and had established formal communication with Temasek.76

Unlike Temasek and its single broad-based goal of delivering sustainable value over the long term, SOEs

in other geographic regions could be tasked with multiple goals, some of which might be conflicting such

as promoting technological productivity vs. reducing unemployment. Also, some governments might find

difficulty in taking a hands-off approach in the operations of their SOEs or might intervene out of political

reasons. Essentially, the Temasek model had been developed in a small country with strong rule of law,

an uncomplicated governing framework and a reputation for low corruption and high efficiency. Would the

Temasek model be valid in a different context and setting?

On 13 July 2015, the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Bill was passed. Through

this legislation, Temasek was added as a contributor to the Net Investment Returns (NIR) framework,

which permits government spending of a maximum of 50 percent of long-term expected real returns

generated from net assets managed by GIC 77, the Monetary Authority of Singapore and Temasek

Holdings. As the long-term expected real return rates are averaged out over a 20-year period and

reviewed annually, they would be less vulnerable to cyclical volatility and short-term fluctuations and

economic pressure. With Temasek’s inclusion into the NIR framework and the subsequently bigger

revenue pool, the NIR contribution to the national budget would rise from 2 percent to 3 percent over the

next five years with higher fiscal spending projected in anticipation of greater healthcare costs, transport

investments and human capital investments.78 What implications would Temasek’s inclusion into the NIR

framework present for the company, its governance, the protection of its past reserves and its future?

As Temasek entered upon a new phase in its history where new challenges and responsibilities awaited

the company, one constant remained. Corporate governance would continue to be the cornerstone for the

growth and success of Temasek and its portfolio companies, and its importance would likely grow.

73

Temasek Holdings. (2015). Temasek Review 2015, p. 62.

74

Sim, I., Thomsen, S., & Yeong, G. (2014). The State as shareholder: The case of Singapore. Singapore:

Chartered Institute of Management Accountants; Centre for Governance, Institutions and Organisations, NUS

75

Soko, M. (2015). Lessons from SOE governance reforms in Singapore. Retrieved October 19, 2015, from

http://www.gsb.uct.ac.za/Newsrunner/Story.asp?intContentID=2503

76

China state company research head eyes Temasek model, not Russia. (2015, October 2). Bloomberg news.

77

GIC is wholly owned by the Government of Singapore and manages Singapore’s foreign reserves.

78

Second Reading Speech by Mr Tharman Shanmugaratnam, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Finance, for

the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore (Amendment) Bill. Retrieved January 28, 2016 from

http://www.mof.gov.sg/news-reader/articleid/1513

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 19

ABCC-2016-001

EXHIBIT 1A

TEMASEK CHARTER 2002

Temasek Holdings holds and manages the Singapore Government’s investments in companies, for the

long term benefit of Singapore.

By nurturing successful and vibrant international businesses from its stable of companies, Temasek will

help to broaden and deepen Singapore’s economic base.

Temasek will work with its companies to:

▶ ▶ Values

Promote and maintain a strong culture of integrity, meritocracy, excellence and innovation;

▶ ▶ Focus

Foster a strong focus on core competence, value creation, customer fulfilment and shareholder returns;

and divest non-core businesses, so as to maximise long-term shareholder benefit;

▶ ▶ Human Capital

Nurture and cultivate a strong and internationally competitive cadre of board and management leadership,

as well as outstanding employees to build successful businesses;

▶ ▶ Sustainable Growth

Support and institutionalise high standards of business leadership, financial discipline, operational

excellence and corporate governance to achieve scaleable and sustainable growth; and

▶ ▶ Strategic Development

Shape strategic developments, including consolidations, mergers, acquisitions, rationalisation or

collaborations as appropriate, to build significant international or regional businesses.

Temasek will divest businesses which are no longer relevant or have no international growth potential.

Temasek may also, from time to time, invest in new businesses, in order to nurture new industry clusters

in Singapore.

This document is authorized for use only by Yos Sunitiyoso in 2018.

For the exclusive use of Y. Sunitiyoso, 2018.

Page 20

ABCC-2016-001

EXHIBIT 1B

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT OF TEMASEK CHARTER 2002

Background

1. Temasek Holdings was formed in 1974 as a focal point to hold and manage the Singapore

government’s investments in companies for the long-term benefit of Singapore.

2. Many of its businesses have their roots in the history of Singapore’s economic development. For

instance, Singapore Airlines was formed through the demerger of Malaysia-Singapore Airlines after

Singapore’s separation from Malaysia, and SembCorp Marine evolved from the commercialisation of

the naval dockyard facilities when British military forces withdrew from the Far East. In each case, the

goals were to develop economically viable businesses, retain and create jobs, and contribute to

Singapore’s economic survival, progress and prosperity.

Relationship with Temasek Companies

1. In the next phase of Singapore’s economic development, Temasek aims to build and nurture

internationally competitive businesses. These can leverage on Singapore’s competitive strengths, and

in turn, enhance Singapore’s economic resilience.

2. Temasek expects all its companies to continually innovate, explore new technologies or markets,

operate on sound commercial principles, and deliver commercial returns in a globally competitive

environment.

3. Temasek will exercise its shareholder rights to influence the strategic directions of its companies. But it

does not involve itself in their day-to-day commercial decisions.

4. Temasek will continually review its stable of companies, and rationalise or consolidate them where it

makes commercial and strategic business sense, so as to enhance long-term shareholder returns.

Group A Businesses – Government Ownership and Control

1. Government needs to own and control companies for various reasons. These include:

Critical resources – where ownership of a resource is critical to Singapore’s security or economic

well-being, or where the business is a natural domestic monopoly for which a market-based

regulatory framework has not yet been established. These include water, power and gas grids,