Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Hilado vs. David

Enviado por

Dagee LlamasDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Hilado vs. David

Enviado por

Dagee LlamasDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

G.R. No.

L-961 September 21, 1949 (a) That you were the equitable owner of

the property described in the complaint,

BLANDINA GAMBOA HILADO, petitioner, as the same was purchased and/or built

vs. with funds exclusively belonging to you,

JOSE GUTIERREZ DAVID, VICENTE J. that is to say, the houses and lot

FRANCISCO, JACOB ASSAD and SELIM pertained to your paraphernal estate;

JACOB ASSAD, respondents.

(b) That on May 3, 1943, the legal title to

Delgado, Dizon and Flores for petitioner. the property was with your husband, Mr.

Vicente J. Francisco for respondents. Serafin P. Hilado; and

TUASON, J.: (c) That the property was sold by Mr.

Hilado without your knowledge on the

aforesaid date of May 3, 1943.

It appears that on April 23, 1945, Blandina

Gamboa Hilado brought an action against Selim

Jacob Assad to annul the sale of several houses Upon the foregoing facts, I am of the

and lot executed during the Japanese opinion that your action against Mr.

occupation by Mrs. Hilado's now deceased Assad will not ordinarily prosper. Mr.

husband. Assad had the right to presume that

your husband had the legal right to

dispose of the property as the transfer

On May 14, Attorneys Ohnick, Velilla and

certificate of title was in his name.

Balonkita filed an answer on behalf of the

defendant; and on June 15, Attorneys Delgado, Moreover, the price of P110,000 in

Dizon, Flores and Rodrigo registered their Japanese military notes, as of May 3,

1943, does not quite strike me as so

appearance as counsel for the plaintiff. On

grossly inadequate as to warrant the

October 5, these attorneys filed an amended

annulment of the sale. I believe, lastly,

complaint by including Jacob Assad as party

defendant. that the transaction cannot be avoided

merely because it was made during the

Japanese occupation, nor on the simple

On January 28, 1946, Attorney Francisco allegation that the real purchaser was

entered his appearance as attorney of record for not a citizen of the Philippines. On his

the defendant in substitution for Attorney last point, furthermore, I expect that you

Ohnick, Velilla and Balonkita who had withdrawn will have great difficulty in proving that

from the case. the real purchaser was other than Mr.

Assad, considering that death has

On May 29, Attorney Dizon, in the name of his already sealed your husband's lips and

firm, wrote Attorney Francisco urging him to he cannot now testify as to the

discontinue representing the defendants on the circumstances of the sale.

ground that their client had consulted with him

about her case, on which occasion, it was For the foregoing reasons, I regret to

alleged, "she turned over the papers" to Attorney advise you that I cannot appear in the

Francisco, and the latter sent her a written proceedings in your behalf. The records

opinion. Not receiving any answer to this of the case you loaned to me are

suggestion, Attorney Delgado, Dizon, Flores and herewith returned.

Rodrigo on June 3, 1946, filed a formal motion

with the court, wherein the case was and is

pending, to disqualify Attorney Francisco. Yours very truly,

Attorney Francisco's letter to plaintiff, mentioned (Sgd.) VICENTE J. FRANCISCO

above and identified as Exhibit A, is in full as

follows:

VJF/Rag.

VICENTE J. FRANCISCO

Attorney-at-Law In his answer to plaintiff's attorneys' complaint,

1462 Estrada, Manila Attorney Francisco alleged that about May,

1945, a real estate broker came to his office in

connection with the legal separation of a woman

July 13, 1945. who had been deserted by her husband, and

also told him (Francisco) that there was a

pending suit brought by Mrs. Hilado against a

Mrs. Blandina Gamboa Hilado certain Syrian to annul the sale of a real estate

Manila, Philippines which the deceased Serafin Hilado had made to

the Syrian during the Japanese occupation; that

My dear Mrs. Hilado: this woman asked him if he was willing to accept

the case if the Syrian should give it to him; that

he told the woman that the sales of real property

From the papers you submitted to me in

during the Japanese regime were valid even

connection with civil case No. 70075 of

though it was paid for in Japanese military

the Court of First Instance of Manila,

notes; that this being his opinion, he told his

entitled "Blandina Gamboa Hilado vs. S.

visitor he would have no objection to defending

J. Assad," I find that the basic facts

the Syrian;

which brought about the controversy

between you and the defendant therein

are as follows:

That one month afterwards, Mrs. Hilado came to Stripped of disputed details and collateral

see him about a suit she had instituted against a matters, this much is undoubted: That Attorney

certain Syrian to annul the conveyance of a real Francisco's law firm mailed to the plaintiff a

estate which her husband had made; that written opinion over his signature on the merits

according to her the case was in the hands of of her case; that this opinion was reached on the

Attorneys Delgado and Dizon, but she wanted to basis of papers she had submitted at his office;

take it away from them; that as he had known that Mrs. Hilado's purpose in submitting those

the plaintiff's deceased husband he did not papers was to secure Attorney Francisco's

hesitate to tell her frankly that hers was a lost professional services. Granting the facts to be

case for the same reason he had told the broker; no more than these, we agree with petitioner's

that Mrs. Hilado retorted that the basis of her counsel that the relation of attorney and client

action was not that the money paid her husband between Attorney Francisco and Mrs. Hilado

was Japanese military notes, but that the ensued. The following rules accord with the

premises were her private and exclusive ethics of the legal profession and meet with our

property; that she requested him to read the approval:

complaint to be convinced that this was the

theory of her suit; that he then asked Mrs. Hilado In order to constitute the relation (of

if there was a Torrens title to the property and attorney and client) a professional one

she answered yes, in the name of her husband; and not merely one of principal and

that he told Mrs. Hilado that if the property was agent, the attorneys must be employed

registered in her husband's favor, her case either to give advice upon a legal point,

would not prosper either; to prosecute or defend an action in court

of justice, or to prepare and draft, in

That some days afterward, upon arrival at his legal form such papers as deeds, bills,

law office on Estrada street, he was informed by contracts and the like. (Atkinson vs.

Attorney Federico Agrava, his assistant, that Howlett, 11 Ky. Law Rep. (abstract),

Mrs. Hilado had dropped in looking for him and 364; cited in Vol. 88, A. L. R., p. 6.)

that when he, Agrava, learned that Mrs. Hilado's

visit concerned legal matters he attended to her To constitute professional employment it

and requested her to leave the "expediente" is not essential that the client should

which she was carrying, and she did; that he told have employed the attorney

Attorney Agrava that the firm should not handle professionally on any previous occasion.

Mrs. Hilado's case and he should return the . . . It is not necessary that any retainer

papers, calling Agrava's attention to what he should have been paid, promised, or

(Francisco) already had said to Mrs. Hilado; charged for; neither is it material that the

attorney consulted did not afterward

That several days later, the stenographer in his undertake the case about which the

law office, Teofilo Ragodon, showed him a letter consultation was had. If a person, in

which had been dictated in English by Mr. respect to his business affairs or

Agrava, returning the "expedients" to Mrs. troubles of any kind, consults with his

Hilado; that Ragodon told him (Attorney attorney in his professional capacity with

Francisco) upon Attorney Agrava's request that the view to obtaining professional advice

Agrava thought it more proper to explain to Mrs. or assistance, and the attorney

Hilado the reasons why her case was rejected; voluntarily permits or acquiesces in such

that he forthwith signed the letter without reading consultation, then the professional

it and without keeping it for a minute in his employment must be regarded as

possession; that he never saw Mrs. Hilado since established. . . . (5 Jones Commentaries

their last meeting until she talked to him at on Evidence, pp. 4118-4119.)

the MANILA HOTEL about a proposed

extrajudicial settlement of the case; An attorney is employed-that is, he is

engaged in his professional capacity as

That in January, 1946, Assad was in his office to a lawyer or counselor-when he is

request him to handle his case stating that his listening to his client's preliminary

American lawyer had gone to the States and left statement of his case, or when he is

the case in the hands of other attorneys; that he giving advice thereon, just as truly as

accepted the retainer and on January 28, 1946, when he is drawing his client's

entered his appearance. pleadings, or advocating his client's

cause in open court. (Denver Tramway

Attorney Francisco filed an affidavit of Co. vs. Owens, 20 Colo., 107; 36 P.,

stenographer Ragodon in corroboration of his 848.)

answer.

Formality is not an essential element of

The judge trying the case, Honorable Jose the employment of an attorney. The

Gutierrez David, later promoted to the Court of contract may be express or implied and

Appeals, dismissed the complaint. His Honor it is sufficient that the advice and

believed that no information other than that assistance of the attorney is sought and

already alleged in plaintiff's complaint in the received, in matters pertinent to his

main cause was conveyed to Attorney profession. An acceptance of the

Francisco, and concluded that the intercourse relation is implied on the part of the

between the plaintiff and the respondent did not attorney from his acting in behalf of his

attain the point of creating the relation of client in pursuance of a request by the

attorney and client. latter. (7 C. J. S., 848-849; see Hirach

Bros. and Co. vs. R. E. Kennington Co.,

88 A. L. R., 1.)

Section 26 (e), Rule 123 of the Rules of Court This rule has been so strictly that it has

provides that "an attorney cannot, without the been held an attorney, on terminating

consent of his client, be examined as to any his employment, cannot thereafter act

communication made by the client to him, or his as counsel against his client in the same

advice given thereon in the course of general matter, even though, while

professional employment;" and section 19 (e) of acting for his former client, he acquired

Rule 127 imposes upon an attorney the duty "to no knowledge which could operate to

maintain inviolate the confidence, and at every his client's disadvantage in the

peril to himself, to preserve the secrets of his subsequent adverse employment.

client." There is no law or provision in the Rules (Pierce vs. Palmer [1910], 31 R. I., 432;

of Court prohibiting attorneys in express terms 77 Atl., 201, Ann. Cas., 1912S, 181.)

from acting on behalf of both parties to a

controversy whose interests are opposed to Communications between attorney and client

each other, but such prohibition is necessarily are, in a great number of litigations, a

implied in the injunctions above quoted. (In complicated affair, consisting of entangled

re De la Rosa, 27 Phil., 258.) In fact the relevant and irrelevant, secret and well known

prohibition derives validity from sources higher facts. In the complexity of what is said in the

than written laws and rules. As has been aptly course of the dealings between an attorney and

said in In re Merron, 22 N. M., 252, L.R.A., a client, inquiry of the nature suggested would

1917B, 378, "information so received is sacred lead to the revelation, in advance of the trial, of

to the employment to which it pertains," and "to other matters that might only further prejudice

permit it to be used in the interest of another, or, the complainant's cause. And the theory would

worse still, in the interest of the adverse party, is be productive of other un salutary results. To

to strike at the element of confidence which lies make the passing of confidential communication

at the basis of, and affords the essential security a condition precedent; i.e., to make the

in, the relation of attorney and client." employment conditioned on the scope and

character of the knowledge acquired by an

That only copies of pleadings already filed in attorney in determining his right to change sides,

court were furnished to Attorney Agrava and would not enhance the freedom of litigants,

that, this being so, no secret communication was which is to be sedulously fostered, to consult

transmitted to him by the plaintiff, would not vary with lawyers upon what they believe are their

the situation even if we should discard Mrs. rights in litigation. The condition would of

Hilado's statement that other papers, personal necessity call for an investigation of what

and private in character, were turned in by her. information the attorney has received and in

Precedents are at hand to support the doctrine what way it is or it is not in conflict with his new

that the mere relation of attorney and client position. Litigants would in consequence be

ought to preclude the attorney from accepting wary in going to an attorney, lest by an

the opposite party's retainer in the same unfortunate turn of the proceedings, if an

litigation regardless of what information was investigation be held, the court should accept

received by him from his first client. the attorney's inaccurate version of the facts that

came to him. "Now the abstinence from seeking

The principle which forbids an attorney legal advice in a good cause is by hypothesis an

who has been engaged to represent a evil which is fatal to the administration of

client from thereafter appearing on justice." (John H. Wigmore's Evidence, 1923,

behalf of the client's opponent applies Section 2285, 2290, 2291.)

equally even though during the

continuance of the employment nothing Hence the necessity of setting down the

of a confidential nature was revealed to existence of the bare relationship of attorney

the attorney by the client. (Christian vs. and client as the yardstick for testing

Waialua Agricultural Co., 30 Hawaii, incompatibility of interests. This stern rule is

553, Footnote 7, C. J. S., 828.) designed not alone to prevent the dishonest

practitioner from fraudulent conduct, but as well

Where it appeared that an attorney, to protect the honest lawyer from unfounded

representing one party in litigation, had suspicion of unprofessional practice. (Strong vs.

formerly represented the adverse party Int. Bldg., etc.; Ass'n, 183 Ill., 97; 47 L.R.A.,

with respect to the same matter involved 792.) It is founded on principles of public policy,

in the litigation, the court need not on good taste. As has been said in another

inquire as to how much knowledge the case, the question is not necessarily one of the

attorney acquired from his former during rights of the parties, but as to whether the

that relationship, before refusing to attorney has adhered to proper professional

permit the attorney to represent the standard. With these thoughts in mind, it

adverse party. (Brown vs. Miller, 52 behooves attorneys, like Caesar's wife, not only

App. D. C. 330; 286, F. 994.) to keep inviolate the client's confidence, but also

to avoid the appearance of treachery and

double-dealing. Only thus can litigants be

In order that a court may prevent an

encouraged to entrust their secrets to their

attorney from appearing against a

attorneys which is of paramount importance in

former client, it is unnecessary that the

the administration of justice.

ascertain in detail the extent to which

the former client's affairs might have a

bearing on the matters involved in the So without impugning respondent's good faith,

subsequent litigation on the attorney's we nevertheless can not sanction his taking up

knowledge thereof. (Boyd vs. Second the cause of the adversary of the party who had

Judicial Dist. Court, 274 P., 7; 51 Nev., sought and obtained legal advice from his firm;

264.) this, not necessarily to prevent any injustice to

the plaintiff but to keep above reproach the appearance of an attorney was allowed even on

honor and integrity of the courts and of the bar. appeal as a ground for reversal of the judgment.

Without condemning the respondents conduct In that case, in which throughout the conduct of

as dishonest, corrupt, or fraudulent, we do the cause in the court below the attorney had

believe that upon the admitted facts it is highly in been suffered so to act without objection, the

expedient. It had the tendency to bring the court said: "We are all of the one mind, that the

profession, of which he is a distinguished right of the appellee to make his objection has

member, "into public disrepute and suspicion not lapsed by reason of failure to make it

and undermine the integrity of justice." sooner; that professional confidence once

reposed can never be divested by expiration of

There is in legal practice what called "retaining professional employment." (Nickels vs. Griffin, 1

fee," the purpose of which stems from the Wash. Terr., 374, 321 A. L. R. 1316.)

realization that the attorney is disabled from

acting as counsel for the other side after he has The complaint that petitioner's remedy is by

given professional advice to the opposite party, appeal and not by certiorari deserves scant

even if he should decline to perform the attention. The courts have summary jurisdiction

contemplated services on behalf of the latter. It to protect the rights of the parties and the public

is to prevent undue hardship on the attorney from any conduct of attorneys prejudicial to the

resulting from the rigid observance of the rule administration of the justice. The summary

that a separate and independent fee for jurisdiction of the courts over attorneys is not

consultation and advice was conceived and confined to requiring them to pay over money

authorized. "A retaining fee is a preliminary fee collected by them but embraces authority to

given to an attorney or counsel to insure and compel them to do whatever specific acts may

secure his future services, and induce him to act be incumbent upon them in their capacity of

for the client. It is intended to remunerate attorneys to perform. The courts from the

counsel for being deprived, by being retained by general principles of equity and policy, will

one party, of the opportunity of rendering always look into the dealings between attorneys

services to the other and of receiving pay from and clients and guard the latter from any undue

him, and the payment of such fee, in the consequences resulting from a situation in which

absence of an express understanding to the they may stand unequal. The courts acts on the

contrary, is neither made nor received in same principles whether the undertaking is to

payment of the services contemplated; its appear, or, for that matter, not to appear, to

payment has no relation to the obligation of the answer declaration, etc. (6 C.J., 718 C.J.S.,

client to pay his attorney for the services which 1005.) This summary remedy against attorneys

he has retained him to perform." (7 C.J.S., flows from the facts that they are officers of the

1019.) court where they practice, forming a part of the

machinery of the law for the administration of

The defense that Attorney Agrava wrote the justice and as such subject to the disciplinary

letter Exhibit A and that Attorney Francisco did authority of the courts and to its orders and

not take the trouble of reading it, would not take directions with respect to their relations to the

the case out of the interdiction. If this letter was court as well as to their clients. (Charest vs.

written under the circumstances explained by Bishop, 137 Minn., 102; 162, N.W., 1062, Note

Attorney Francisco and he was unaware of its 26, 7 C. J. S., 1007.) Attorney stand on the

contents, the fact remains that his firm did give same footing as sheriffs and other court officers

Mrs. Hilado a formal professional advice from in respect of matters just mentioned.

which, as heretofore demonstrated, emerged the

relation of attorney and client. This letter binds We conclude therefore that the motion for

and estop him in the same manner and to the disqualification should be allowed. It is so

same degree as if he personally had written it. ordered, without costs.

An information obtained from a client by a

member or assistant of a law firm is information

imparted to the firm. (6 C. J., 628; 7 C. J. S.,

986.) This is not a mere fiction or an arbitrary

rule; for such member or assistant, as in our

case, not only acts in the name and interest of

the firm, but his information, by the nature of his

connection with the firm is available to his

associates or employers. The rule is all the more

to be adhered to where, as in the present

instance, the opinion was actually signed by the

head of the firm and carries his initials intended

to convey the impression that it was dictated by

him personally. No progress could be hoped for

in "the public policy that the client in consulting

his legal adviser ought to be free from

apprehension of disclosure of his confidence," if

the prohibition were not extended to the

attorney's partners, employers or assistants.

The fact that petitioner did not object until after

four months had passed from the date Attorney

Francisco first appeared for the defendants does

not operate as a waiver of her right to ask for his

disqualification. In one case, objection to the

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- W-2 Wage and Tax Statement: Copy B-To Be Filed With Employee's FEDERAL Tax ReturnDocumento1 páginaW-2 Wage and Tax Statement: Copy B-To Be Filed With Employee's FEDERAL Tax ReturnjeminaAinda não há avaliações

- PCM10 LA6741 schematics documentDocumento37 páginasPCM10 LA6741 schematics documentrmartins_239474Ainda não há avaliações

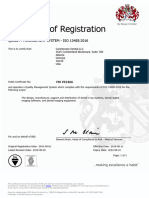

- ISO 13485 - Carestream Dental - Exp 2022Documento2 páginasISO 13485 - Carestream Dental - Exp 2022UyunnAinda não há avaliações

- Smart Mobs Blog Archive Habermas Blows Off Question About The Internet and The Public SphereDocumento3 páginasSmart Mobs Blog Archive Habermas Blows Off Question About The Internet and The Public SpheremaikonchaiderAinda não há avaliações

- LWPYA2 Slide Deck Week 1Documento38 páginasLWPYA2 Slide Deck Week 1Thowbaan LucasAinda não há avaliações

- Canons 17 19Documento22 páginasCanons 17 19Monique Allen Loria100% (1)

- Fdas Quotation SampleDocumento1 páginaFdas Quotation SampleOliver SabadoAinda não há avaliações

- Austerity Doesn't Work - Vote For A Real Alternative: YoungerDocumento1 páginaAusterity Doesn't Work - Vote For A Real Alternative: YoungerpastetableAinda não há avaliações

- 2.8 Commissioner of Lnternal Revenue vs. Algue, Inc., 158 SCRA 9 (1988)Documento10 páginas2.8 Commissioner of Lnternal Revenue vs. Algue, Inc., 158 SCRA 9 (1988)Joseph WallaceAinda não há avaliações

- Drug Free Workplace Act PolicyDocumento8 páginasDrug Free Workplace Act PolicyglitchygachapandaAinda não há avaliações

- Reinstating the Death PenaltyDocumento2 páginasReinstating the Death PenaltyBrayden SmithAinda não há avaliações

- Mutual Funds: A Complete Guide BookDocumento45 páginasMutual Funds: A Complete Guide BookShashi KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Punishment For Offences Against The StateDocumento3 páginasPunishment For Offences Against The StateMOUSOM ROYAinda não há avaliações

- Pop Art: Summer Flip FlopsDocumento12 páginasPop Art: Summer Flip FlopssgsoniasgAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Political System-SyllabusDocumento2 páginasIndian Political System-SyllabusJason DunlapAinda não há avaliações

- The Three Principles of The CovenantsDocumento3 páginasThe Three Principles of The CovenantsMarcos C. Thaler100% (1)

- QNet FAQDocumento2 páginasQNet FAQDeepak GoelAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Resignation LetterDocumento15 páginasSample Resignation LetterJohnson Mallibago71% (7)

- FIT EdoraDocumento8 páginasFIT EdoraKaung MyatToeAinda não há avaliações

- Abraham 01Documento29 páginasAbraham 01cornchadwickAinda não há avaliações

- No. 49 "Jehovah Will Treat His Loyal One in A Special Way"Documento5 páginasNo. 49 "Jehovah Will Treat His Loyal One in A Special Way"api-517901424Ainda não há avaliações

- Etm 2011 7 24 8Documento1 páginaEtm 2011 7 24 8Varun GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- 14th Finance CommissionDocumento4 páginas14th Finance CommissionMayuresh SrivastavaAinda não há avaliações

- Module 2 - Part III - UpdatedDocumento38 páginasModule 2 - Part III - UpdatedDhriti NayyarAinda não há avaliações

- Income Statement and Related Information: Intermediate AccountingDocumento64 páginasIncome Statement and Related Information: Intermediate AccountingAdnan AbirAinda não há avaliações

- Bestway Cement Limited: Please Carefully Read The Guidelines On The Last Page Before Filling This FormDocumento8 páginasBestway Cement Limited: Please Carefully Read The Guidelines On The Last Page Before Filling This FormMuzzamilAinda não há avaliações

- Newsweek v. IACDocumento2 páginasNewsweek v. IACKlerkxzAinda não há avaliações

- Lonzanida Vs ComelecDocumento2 páginasLonzanida Vs ComelectimothymarkmaderazoAinda não há avaliações

- Brief History of PhilippinesDocumento6 páginasBrief History of PhilippinesIts Me MGAinda não há avaliações

- NELSON MANDELA Worksheet Video BIsDocumento3 páginasNELSON MANDELA Worksheet Video BIsAngel Angeleri-priftis.Ainda não há avaliações