Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Falling Through The Cracks, Student Homelessness in RI

Enviado por

Anthony VegaTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Falling Through The Cracks, Student Homelessness in RI

Enviado por

Anthony VegaDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

MARCH 2019

SCHOLAR SERIES

Contemporary Issues in Housing

Falling Through the Cracks:

Homeless Students in Rhode Island

By Marjorie Pang Si En

HousingWorks RI at Roger Williams University is a

clearinghouse of information about housing in Rhode

Island. We conduct research and analyze data to inform

public policy.

We develop communications strategies and promote

dialogue about the relationship between housing and the

state’s economic future and our residents’ well-being.

SCHOLAR SERIES

HousingWorks RI at Roger Williams University is pleased

to be able to work with scholars and students across

multiple disciplines in highlighting new research in

housing affordability and related topics.

Falling Through the Cracks:

Homeless Students in Rhode Island

March 2019

By Marjorie Pang Si En

Introduction

Irene Glasser, Ph.D.

Adjunct Lecturer, Anthropology Department, Brown University

Research Associate, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies,

Brown University

It is my pleasure to introduce you to Marjorie homeless situations. The doubled-up homeless are

Pang Si En’s HousingWorks RI: Scholar Series, those families staying, temporarily, with family

“Falling Through the Cracks: Homeless Students or friends. These are the families who are living

in Rhode Island.” This work, which Ms. Pang “under the radar” in terms of accessing help. As you

completed for her thesis in Public Policy at Brown will see in Ms. Pang’s work, here is where Rhode

University, is an in-depth study of the McKinney- Island has challenges in identifying all students

Vento Homeless Assistance Act (MVHAA) experiencing homelessness, including those who

implementation in Rhode Island. Ms. Pang was are living doubled-up. In 2014-15 Rhode Island

able to analyze the strengths and weaknesses identified only 9.7 percent of extremely poor

of the MVHAA’s implementation and make children and youth as homeless instead of the

recommendations for strengthening the program. 30 percent, which is the national estimate of the

percentage of extremely poor children, and youth

As a researcher and advocate in the field of in grades K-12 who will experience homelessness.

homelessness, I was very impressed by the intent

of the MVHAA, which ensures that the student Ms. Pang has identified some of the reasons for

who is experiencing homelessness continues to the under identification of children and youth

progress in their education and is not impeded experiencing homelessness in Rhode Island. These

in their academic and social development by an reasons include the lack of collaboration with

episode of homelessness. The MVHAA provides community organizations who are in touch with

funding and mechanisms to help the student doubled-up families, the fact that some of the Local

experiencing homelessness in areas such as Education Agencies (LEAs) do not apply for the

providing transportation to and from the school of MVHAA subgrants that could give the LEAs more

origin, providing school supplies and appropriate money for outreach, and the insufficient training

clothing, tutoring support, and waiving fees for of the LEA liaisons and other school personnel

participation in extracurricular activities. in the art of identifying children and youth

who are experiencing homelessness. Ms. Pang’s

A very strong aspect of the MVHAA is that it recommendations would enable Rhode Island to

recognizes not just the children and youth living greatly extend the reach of the MVHAA and ensure

with their families in homeless shelters, but also the educational development of children and youth

the far greater number living in doubled-up experiencing homelessness in Rhode Island.

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 1

Falling Through the Cracks:

Homeless Students in Rhode Island Based on these findings and a survey of best

practices from other states, this research puts

Summary forth the following recommendations:

“Falling Through the Cracks: Homeless Students in Rhode • Improve and increase the contacts between the

Island” is a case study which examines the effectiveness homeless education liaisons and family shelter staff

of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act • Minimize the barriers to Local Education Agencies

(MVHAA) as implemented in Rhode Island from a (LEAs) receiving subgrants from the MVHAA

bottom-up perspective and outcomes-based approach.

• Provide for school-based homeless education

The MVHAA is a federal law that provides children and

youth experiencing homelessness with the protections liaisons in addition to the LEA-based homeless

and services that will allow them to enroll in and attend education liaisons

school, complete high school, and continue on to higher • Institute mandatory training regarding child and

education. Some of the provisions of the MVHAA family homelessness for school personnel

include transportation to and from the school of origin

• Increase community awareness about homelessness

when needed, referrals to community agencies that can

provide the needed school supplies including appropriate • Increase educational support for children

clothing, tutoring support, fee waivers for participation experiencing homelessness with an emphasis on

in extracurricular activities, as well as other services youth experiencing homelessness

needed to support their academic success and wellbeing.1

In 2017, Rhode Island received $263,597 for the MVHAA.2

These funds supported subgrants to five school districts

to provide additional resources to identify and serve Introduction:

students experiencing homelessness. Child and Family Homelessness

This study finds that the MVHAA implemented in

Families with children are among the fastest growing

Rhode Island under-identifies students experiencing

segments of the homeless population.4 School-age

homelessness, and may therefore impede those students’

children and youth account for nearly 40 percent of

access to resources to which they are legally entitled.

the total homeless population in the United States.5

Under-identification is compounded by the lack of federal

and state funding for some of the school districts. A key According to Education for Homeless Children and

to the implementation of the MVHAA is the homeless Youth (EHCY) program data, the population of children

education liaisons, and we found that there was limited and youth experiencing homelessness has been steadily

collaboration between the homeless education liaisons increasing. From the 2006-07 School Year (SY) to the

and other service providers for low-income Rhode 2015-16 SY, the total number of identified children and

Islanders in most cities and towns. According to the youth experiencing homelessness in public schools

national study Out of the Shadows: A State-by-State approximately doubled from 679,724 to 1,366,520

Ranking of Accountability for Homeless Students, Rhode students.6 This is a disturbing trend, as research shows

Island is one of the worst performing states at identifying that children and youth experiencing homelessness are

children and youth experiencing homelessness.3 at greater risk of negative educational outcomes such as

learning disabilities, dropping out, and other behavioral

and health problems.7

2 HousingWorks RI Scholar Series

The McKinney-Vento

Homeless Assistance Act

Timely educational intervention is shown to change

the developmental trajectories of children and youth

experiencing homelessness8 who require access to a

quality education to overcome the many educational

challenges associated with homelessness. The MVHAA

was intended to mitigate the negative educational

outcomes homeless youth experience; it was the first

federal law regulating how Local Education Agencies

(LEAs)9 address the educational needs of students

experiencing homelessness.10 LEAs administer the

policies and procedures of the MVHAA and decide on

the use of funding for the education of children and

youth experiencing homelessness in their jurisdiction.

Nearly all of the MVHAA requirements fall under LEAs

and schools rather than state-level entities. However,

despite the provisions of the MVHAA, it is not clear that

its implementation has effectively and systematically

supported children and youth experiencing homelessness.

Under the MVHAA, LEA’s are required to offer the following assistance:

1) Students experiencing homelessness, who move, have the right to remain in their schools of origin (i.e., the

school the student attended when permanently housed or in which the student was last enrolled, including

preschools) if that is in the student’s best interest;

2) If it is in the student’s best interest to change schools, students experiencing homelessness must be

immediately enrolled in a new school, even if they do not have the records normally required for enrollment;

3) Transportation must be provided to or from a student’s school of origin, at the request of a parent, guardian,

or, in the case of an unaccompanied youth, the local homeless education liaison;

4) Students experiencing homelessness must have access to all programs and services for which they are

eligible, including special education services, preschool, school nutrition programs, language assistance for

English learners, career and technical education, gifted and talented programs, magnet schools, charter

schools, summer learning, online learning, and before- and after-school care;

5) Unaccompanied youths must be accorded specific protections, including immediate enrollment in school

without proof of guardianship; and

6) Parents, guardians, and unaccompanied youths have the right to dispute an eligibility, school selection, or

enrollment decision.11

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 3

The MVHAA is, in theory, the key to positively changing homeless students are doubled-up rather than in

the education trajectory of many children and youth homeless shelters.17

experiencing homelessness. The Act outlines educational

services and supports for identified homeless students, The MVHAA was amended and reauthorized in

and captures more children and youth experiencing 1990, 1994, 2002, and 2015 in response to various

homelessness than other federal agencies in its broad implementation and structural problems that failed to

definition of homelessness. adequately identify and support children and youth

experiencing homelessness.18 The current MVHAA is

The MVHAA defines homeless children and youth12 based on the 2015 amendment and reauthorization of the

as those living in emergency and transitional shelters, MVHAA. The 2015 amendment was promulgated when

doubled-up in homes with relatives and friends, and Congress passed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

living in hotels and motels, cars, campsites, parks, and ESSA included tighter regulation for schools and LEAs

other public places. 13

It includes doubled-up families 14

in the planning and provision of services to students

within the definition of homelessness, which the U.S. experiencing homelessness, better protections for

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) students facing possible school transfers, and an increase

excludes.15 The term doubled-up refers to a situation in authorized funding for the EHCY program within

where individuals are unable to maintain their housing the U.S. Department of Education.19 However, despite

situation and are forced to stay with a series of friends the various amendments made, there are still persistent

and/or extended family members.16 This broader and problems with the implementation of the provisions

more inclusive definition of homelessness is important under the MVHAA. Resource allocation, sustainable

in capturing the majority of children and youth funding, and compliance with the requirements of the

experiencing homelessness, who qualify for support law remain difficult for local jurisdictions.

and assistance as, nationally, the majority of identified

Methodology of the Study

This case study uses a mixed methods approach that communication with shelter staff in order to set up the

includes qualitative interviews with state coordinators, interviews. In addition, one meeting of mothers in one

local homeless education liaisons, shelter staff, of the shelters was observed. To gather insight into the

and families experiencing homelessness, as well as policies and systems overseeing the implementation

quantitative educational outcomes data from the Rhode of MVHAA, three MVHAA coordinators were

Island Department of Education (RIDE). The qualitative interviewed. The quantitative data includes educational

data are based on interviews with eight of Rhode outcome measures for children and youth experiencing

Island’s homeless education liaisons and 14 mothers homelessness, which were analyzed within the context

experiencing homelessness in two of Rhode Island’s four of educational outcome measures for all Rhode Island

family homeless shelters. There was also frequent children and youth.

4 HousingWorks RI Scholar Series

Implementation of the MVHAA

The lack of an official metric for measuring the Survey (ACS) data, is a standard proxy for the

effectiveness of states at implementing the MVHAA potential number of students experiencing

limits the accountability of states and school homelessness since the true number of students

districts. However, the Institute of Child, Poverty, experiencing homelessness cannot be calculated.

and Homelessness published a report in 2017, The Accountability Study assumes that unidentified

titled Out of the Shadows: A State-by-State Ranking homeless students live in each state and LEA.

of Accountability for Homeless Students (“The Identifying a greater portion of children in extreme

Accountability Study”), to evaluate the performance poverty as homeless indicates that states or LEAs are

of states at identifying and supporting homeless more effectively identifying students experiencing

students. The Accountability Study used five homelessness. This measure will help to assess

indicators to measure the effectiveness of states whether states or LEAs are realizing the intent of

at implementing the MVHAA. The five indicators the law. There is also the possibility that the states

were: the percentage of children in Head Start who with fewer than 30 percent of extremely poor

experience homelessness; children experiencing children identified as homeless have an abundance of

homelessness as a percentage of poor children in pre- affordable housing, although that does not appear to

kindergarten; children experiencing homelessness be the case in Rhode Island.

as a percentage of extremely poor children in

grades kindergarten-12 (K-12); percentage of all One weakness of this measure is that the number and

students identified as homeless and doubled-up; and percentage of children living in poverty are estimates,

percentage of students experiencing homelessness not actual counts, as the American Community

identified as having a disability.20 Survey is a sample survey. The reliability of these

estimates varies by community. Furthermore, the

This case study focuses on the Homeless Student number of homeless students in each LEA may

Indicator which calculates the number of homeless be influenced by the presence of shelters. Having

children as a percentage of extremely poor children more shelters in an LEA increases the identification

in grades K-12 as one way to assess how well Rhode numbers, as shelters have a high concentration of

Island identifies students experiencing homelessness. homeless students, who are also the most visible

Robust identification is the first step to serving homeless. If LEAs have more shelters, the number of

students experiencing homelessness, as identification students experiencing homelessness as a percent of

is needed to allocate services and resources to the number of children and youth in poverty is likely

each student. to be an overestimation of how well LEAs identify

students experiencing homelessness.

The Accountability Study found that nationally, 30

percent of extremely poor children in grades K-12 Nevertheless, calculating the number of children and

are identified as homeless. Assessing the percentage youth experiencing homelessness as a percentage of

of extremely poor children in each state or LEA, as extremely poor children in each state provides a

captured by the U.S. Census’ American Community good estimate of the relative performance of states

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 5

at identifying children and youth experiencing insufficient resources given to homeless education

homelessness. The ranking of states, from the liaisons to carry out their legal responsibilities

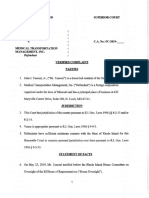

Accountability Study, can be seen in the map below. under the MVHAA, has resulted in many Rhode

Island LEAs seriously under-identifying students

As illustrated by the map, Rhode Island ranks 42nd experiencing homelessness. This issue was found to

in the overall national ranking on the identification be pervasive in the interviews conducted for this

of students experiencing homelessness based on research. None of the homeless education liaisons

the five indicators. 21

The lack of a system-wide interviewed followed a standard protocol to identify

mechanism, with strong protocols for homeless children and youth experiencing homelessness. A few

education liaisons and school personnel to identify noted the difficulty of finding families experiencing

students experiencing homelessness, combined with homelessness.

FIGURE 1 |

MVHAA in Rhode Island: Findings

Identification Levels of Rhode Island LEAs

WA ND

MT

MN

ME

SD WI VT

OR

ID WY MI NY NH

IA MA

NE

PA RI

IL IN OH

NV UT CO CT

KS MO WV NJ

KY VA

CA DE

OK TN NC MD

NM AR

AZ

SC

MS AL GA

TX LA

1-10 (top)

AK

CA FL

11-20

HI 21-30

31-40

Source: The Institute of Children, Poverty and Homelessness, 2017 41-51 (bottom)

6 HousingWorks RI Scholar Series

According to the Accountability Study, Rhode Island liaisons raised when asked about the challenges they

only identified 9.7 percent of the extremely poor faced in implementing the law. Homeless education

children and youth as homeless in the 2014-15 SY. liaisons acknowledged that given the population and

This low identification of students experiencing poverty levels of their LEAs, it is almost certain that

homelessness indicates a high probability that the they are under-identifying the number of students

true number of students experiencing homelessness experiencing homelessness in their jurisdictions. As

is much higher than the reported number. Based

22

one local homeless education liaison put it:

on the findings of the Accountability Study, “states

varied considerably in their ability to identify Goodness gracious, are we really

homeless students, with Alaska, Utah and New York helping everyone? We know we are not.

identifying greater than 50% of extremely poor

students as homeless, while Connecticut and Rhode Despite only identifying a portion of extremely poor

Island identifying fewer than 10%.” From 2011 to students as homeless, the number of children and

2015, there were an estimated 19,432 children and youth identified as homeless in Rhode Island has

youth in extreme poverty each year. This works out continued to increase over the past few years. During

to an estimated 3,945 unidentified children and youth the 2015-16 SY, Rhode Island public school personnel

experiencing homelessness in Rhode Island. 23

reported 1,049 preschool-12 students as homeless, a 5.2

percent increase from the 2013-14 SY.25 This reflects

More than half of the parents interviewed at both the worsening problem of family homelessness and

shelters were not connected to a homeless education the urgent need to improve the effectiveness of the

liaison at the time of the interview, reiterating the MVHAA in Rhode Island.

under-identification problem. However, it is possible

that the parents interviewed had not yet had school

contact because their children were too young.

According to the Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook,

51 percent of the children in Emergency Shelters,

Domestic Violence Shelters and Transitional Housing

Facilities in 2017 were ages 0-5.24

Nevertheless, the fact that the majority of interviewed

parents in shelters had no contact with a homeless

education liaison is concerning as sheltered homeless

are the most visible homeless. If sheltered families are

not connected to homeless education liaisons, then

those who are the least visible and often hidden, such

as families doubling-up with their family or friends,

are very unlikely to be identified.

The identification of children and youth experiencing

homelessness was the key challenge that 62.5 percent

(n=5) of eight interviewed homeless education

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 7

Student Mobility

The student mobility rate of students experiencing homelessness decreased slightly by 7.3 percent from

2013 to 2017, even though it has fluctuated over the years. The student mobility rate for students

experiencing homelessness in Rhode Island is on average three times higher than that of the total Rhode Island

student population.

FIGURE 2 |

Student Mobility of Students Experiencing Homeless vs. the Total RI Student Population

60%-

49.9%

50%- 46.0%

46.4%

43.4% Homeless

41.8%

40%-

30%-

20%-

14% 14% 14% Total RI Students

10%- 13% 13%

0%-

-2013

-2013.5

-2014

-2014.5

-2015

-2015.5

-2016

-2016.5

-2017

-2017.5

Additionally, it is important to note that students experiencing homelessness and students who are housed

are likely to experience different kinds of student mobility. Based on the exit codes, the mobility of students

experiencing homelessness is due to transfers to other public schools in the same LEA, a different LEA, or

a different state.26 There were no students experiencing homelessness recorded for transferring to private

or charter schools in the exit codes. In contrast, for the general student population, there are likely students

recorded in other exit codes, such as transferring to private religiously affiliated, or non-religiously affiliated

schools, and charter schools.

8 HousingWorks RI Scholar Series

Chronic Absenteeism

The chronic absenteeism rate for the total Rhode Island student population was reported in the Rhode Island

Kids Count Factbook for K-3, middle school and high school students separately. The yearly chronic absenteeism

rate for all Rhode Island students was calculated manually by taking the total number of students that were

chronically absent divided by the number of students in Rhode Island that were enrolled for 90 days or more.

FIGURE 3 |

Chronic Absenteeism of Students Experiencing Homeless vs. the Total RI Student Population

40%-

33.9%

35%-

31.6% Homeless

30%-

26.9%

25.0% 26.6%

25%-

20%-

18.88% 19.58% Total RI Students

17.55%

15%- 17.26% 17.18%

10%-

5%-

0%-

-2013

-2013.5

-2014

-2014.5

-2015

-2015.5

-2016

-2016.5

-2017

-2017.5

There is a general upward trend in the chronic absenteeism rates for children experiencing homelessness, which

has increased by 35.6 percent or 8.9 percentage points from 2013 to 2017. In contrast, the chronic absenteeism

rate for all Rhode Island students has had a smaller increase of 13.2 percent. This has resulted in a widening

gap in the chronic absenteeism rate for students experiencing homelessness and the total Rhode Island student

population from 2013 to 2017.

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 9

Suspension Rates

The suspension rates of students experiencing homelessness decreased by 17.4 percent from 14.4 percent in 2011

to 11.9 percent in 2017, but increased in 2014 and 2016, reaching a high of 16.3 percent in 2014. However, the

downward trend in suspension rates of students experiencing homelessness is not conclusive, due to fluctuations

over the years and the lack of data after 2017. The suspension rates for the total student population decreased

by 54.8 percent over that period. The sharp decline in suspension rates for all students in 2012 is due to stricter

Rhode Island laws against suspensions.

FIGURE 4 |

Suspension Rates of Students Experiencing Homelessness vs. Total RI Student Population

35%-

31% 30%

30%-

23% 22%

25%-

19% Total RI Students

17%

20%-

14%

16.3%

15%- 14.3%

14.6% 14.2%

14.4% 11.2% 11.9% Homeless

10%-

5%-

0%-

-2011

-2012

-2013

-2014

-2015

-2016

-2017

In 2012, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a law prohibiting schools from suspending students out of

school solely based on their absenteeism.27 Since then, there have been continued efforts to reduce the high

suspension rates. In June 2016, Governor Raimondo signed a bill into law that “restricted the use of out-of-school

suspensions to situations when a child’s behavior poses a demonstrable threat that cannot be dealt with by other

means and required school districts to identify any racial, ethnic, or special education disparities and develop a

plan to reduce such disparities.”28 This law made it harder for schools to suspend students for minor infractions.29

The 2012 and the 2016 laws have collectively regulated and lowered the number of suspensions for all Rhode

Island students. It is thus worrying that the suspension rates of students experiencing homelessness have not

decreased proportionately over time.

10 HousingWorks RI Scholar Series

Homeless families interviewed also shared that: Persistent Implementation

• Problems with the frontline service delivery of the

Problems with the MVHAA

MVHAA include delayed inter-LEA transportation. Systematic Underfunding

One parent shared that she waited at least 2 months

for state transportation, even though under the Since its inception in 1987, many have argued that

guidelines it is supposed to happen within 48 hours. the MVHAA is chronically underfunded nationwide.

This delay is due to state busing being unable While the funding levels have increased since 1987

to accommodate these transportation requests, to reach $85 million in 2017 through 2020,30 funding

something which education homeless liaisons have increases are not commensurate with the rapidly

little control over. The delay in transportation has led growing needs and number of students experiencing

to students changing schools when they moved to a homelessness, and the increasing requirements for

LEA different from their school of origin. Roughly 40 states and LEAs to abide by the updated versions of

percent (42.9 percent; n=6) of interviewed parents said the MVHAA.

that their children’s education has been disrupted

since moving to the shelter. Very few LEAs in Rhode Island receive subgrants,

which shows a systematic failure to seek appropriate

• Many identified students experiencing homelessness resources for assistance. Providence, the largest LEA

do not get satisfactory educational support, as in Rhode Island, does not receive a subgrant. The

there are few educational programs for students homeless education liaison officers said in interviews

experiencing homelessness. The majority of the that this is a “competitive subgrant,” requiring extra

homeless parents interviewed said that their children work for liaison officers. Some liaisons in smaller

received no extra educational help in school and LEAs with fewer students experiencing homelessness

several sheltered parents said they received no similarly do not apply for it as they think that they

educational support within the shelter. Older youth will not qualify.

in particular have a harder time adjusting in school

because few in-school and after-school programs are

Uneven Distribution of Subgrants

tailored to them and they face greater social pressures

to fit in.

Exacerbating the underfunding problem, the uneven

distribution of MVHAA subgrants throughout the state

• Parents experiencing homelessness whose children

leads to some LEAs lacking funds and being unable

were receiving MVHAA resources said they were

to meet the MVHAA requirements.31 The federal

able to get school supplies, clothing vouchers,

government requires that 75 percent of funding

and other necessities for their children. However,

given to states be distributed to LEAs as three-year

homeless students’ educational experience differed

local subgrant awards. The state may use the rest to

according to their ages, the length of time that

fund their activities related to promoting the needs

they have experienced homelessness, and whether

of children experiencing homelessness in the schools.

they had an Individualized Educational Program

Each LEA that would like to apply for a subgrant, must

(IEP). Having a homeless student advocate within

comply with federally mandated requirements for

the school could greatly improve the support and

the submission of the subgrant application to the State

experience of these students.

Education Agency (SEA). This competitive application

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 11

process for funding McKinney-Vento assistance community connections and familiarity with social

is a challenge to LEAs that do not have the time or processes to adequately support students experiencing

resources to apply. The result is an uneven distribution homelessness.37 Lack of collaboration among different

of funds and implementation of assistance to students actors involved in the implementation of the MVHAA

experiencing homelessness. impedes the provision of services to students

experiencing homelessness.

Limited Collaboration

Lack of Knowledge,

A lack of collaboration among homeless education

Limited Capacity, and

liaisons, school administrators, teachers, service

agencies, and family members limits the effectiveness Weak Accountability of

of the MVHAA at the local level.33 Collaboration Homeless Education Liaisons

is defined as having policies and procedures that

enable interaction with community agencies to The lack of awareness and knowledge of the

provide essential resources and services to families MVHAA by local homeless education liaisons,

experiencing homelessness.34 Collaboration is and the fact that many have other administrative

especially important for implementing the MVHAA jobs within the LEA, reduces their efficiency in

as identifying students experiencing homelessness is implementing the MVHAA.38 In many LEAs, the

often challenging and connecting with local service homeless liaisons are administrators who wear

providers expands the outreach to identify students many hats, such as superintendents or assistant

experiencing homelessness. This case study found superintendents. While the MVHAA mandates

homeless education liaisons interviewed in Rhode annual homeless education liaison trainings, it is

Island that exhibited strong collaboration with local likely insufficient to train homeless education liaisons

agencies had a higher identification rate of students to properly identify and support children and youth

experiencing homelessness. experiencing homelessness. More importantly,

homeless education liaisons often lack the capacity

Different community agencies are also needed to effectively implement the MVHAA. None of the

to provide holistic help to families experiencing homeless education liaisons in Rhode Island are

homelessness, who often have diverse needs. full-time; they all hold other positions, resulting in

Stakeholders have to acknowledge their shared insufficient time to identify and support students

responsibility and make a concerted effort to experiencing homelessness. Of the homeless education

collectively identify students facing homelessness and liaisons interviewed, 75 percent (n=6) failed to

provide them with the appropriate resources.35 conduct outreach to identify children experiencing

homelessness and relied on self-disclosure by families

In theory, collaboration is done through policy- experiencing homelessness, which was the most

mandated local homeless education liaisons who common way of identification. This may contribute

are required to work with other service providers to homeless children and youth going unidentified,

to promote educational stability and opportunity.36 especially if homeless parents are reticent about

However, a study by Hallett, Skrla, and Low found disclosing their housing status. Homeless education

that homeless education liaisons frequently lack key liaisons’ reliance on self-disclosure is likely unable

12 HousingWorks RI Scholar Series

to comprehensively identify hidden families assistance under the MVHAA, and thus may

experiencing homelessness. not report their homelessness to the school. This

contributes to negative outcomes for students

The lack of knowledge and limited capacity of experiencing homelessness, especially those

homeless education liaisons is enabled by the lack doubled-up in homes of family and friends, to be

of accountability, as there is weak enforcement of hidden and unidentified. This lack of identification

their responsibilities. There is no official evaluation denies students experiencing homelessness access

of the effectiveness of homeless education liaisons to services and provisions to which they are legally

at identifying and supporting students experiencing entitled under the MVHAA.39 It is possible that

homelessness. The quality of support that homeless some parents are reticent about revealing their

education liaisons provide to students experiencing homelessness due to fears about having their children

homelessness is also, not measured beyond fulfilling removed from their care.

the basic requirements of the MVHAA, resulting in

limited incentive for homeless education liaisons This limited awareness among families may also be

to perform. due to the lack of outreach conducted by homeless

education liaisons in Rhode Island. For many Rhode

Homeless education liaisons’ capacity is limited Island LEAs, the main resource that homeless

due to other pressing work commitments. Many education liaison officers have to reach students

homeless education liaisons interviewed do not experiencing homelessness is MVHAA posters from

conduct outreach to identify students experiencing the Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE).

homelessness. Instead, they rely on self-disclosure Even then, only some homeless education liaisons

from families experiencing homelessness. This put up these posters in schools.40 These posters are

lack of outreach to identify students experiencing also likely insufficient to create awareness among the

homelessness, who are often hidden and hard community (both service providers to the homeless

to identify, amplifies the problem of under- and the homeless themselves) about a homeless

identification. student’s educational rights under the MVHAA.

Additionally, a lack of awareness about the MVHAA Additionally, even if identified, parents’ lack of

in the community, especially among school personnel awareness of their children’s rights may also limit

that have frequent contact with students, may result the services that they receive, as some provisions

in a failure to identify and provide access to MVHAA under the MVHAA are not affirmative and must

services for students experiencing homelessness. be requested. It is uncertain whether parents or

guardians will make such requests when necessary.

Parents and guardians may simply be unaware of

Parents’ Limited Awareness

this provision of the law, or they may be unable or

of their Children’s unwilling to make a request.41

Educational Rights

Despite the provisions of the MVHAA, parents may

have limited awareness of the legally guaranteed

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 13

Policy Recommendations for Rhode Island

Based on best practices of other states that rank highly in identifying children and youth

experiencing homelessness, there are several opportunities for Rhode Island to improve assistance

to this population.42 Below are specific recommendations that are feasible in Rhode Island:

1) To improve identification, homeless education liaisons should have direct

relationships with local shelter staff and other community workers who operate

inside the social network of families experiencing homelessness.

Stronger relationships between homeless education liaisons and local service providers

is necessary to expand the network of identification and service support to students

experiencing homelessness. To increase identification, homeless education liaisons should

establish ongoing coordination with local shelter staff. In this way, those families with school-

aged children, seeking shelter, can be referred directly to a liaison for MVHAA assistance.

This is an immediate solution to the under-identified students living in shelters.

For the population of students who are doubled-up, living in cars, couch surfing, or have run away

from home, it is more difficult to improve identification. However, it is recommended that liaisons

develop strong relationships with social service organizations that touch this population (e.g., outreach

workers). For example, collaboration with Head Start programs: Women, Infants and Children

(WIC); Department of Human Services; home visiting programs; local shelters; school personnel; and

other local service providers can increase identification and implementation of MVHAA services.

2) Minimize barriers to LEAs receiving subgrants and increase funding.

The lack of LEA funding is also compounded by the uneven distribution of subgrants

across LEAs in Rhode Island. Currently, many large LEAs with high numbers of children

and youth experiencing homelessness do not apply for or receive subgrants. Greater

assistance to homeless education liaisons in applying for the subgrant is crucial.

3) Rhode Island should have school-based homeless education liaisons

in addition to the LEA-based homeless education liaisons.

The MVHAA program should consider instituting school-based homeless education liaisons,

in addition to LEA homeless education liaisons. School-based homeless education liaisons can

be the school counselor, or other personnel who have close contact with students. School-

based homeless education liaisons can improve identification of students experiencing

homelessness and provide immediate access to MVHAA services.43 Some Rhode Island

shelters already recognize the effectiveness of connecting directly with schools by bypassing

the homeless education liaisons in order to access services for students in need.44

14 HousingWorks RI Scholar Series

4) Mandatory training for school personnel.

In order to effectively advance services and supports to students experiencing homelessness,

mandatory trainings for school personnel are recommended. Trainings should include requirements

of the MVHAA, how to recognize signs of homelessness, and how to direct students experiencing

homelessness to homeless education liaisons. This can increase the likelihood of successful

identification and referral of students experiencing homelessness to homeless education liaisons.

Training is especially important for new principals and secretaries before they start the school year

in August, as principals and secretaries receive a lot of calls about families who are either moving

into the shelter or come in from outside the community during the school registration period.

5) Greater community awareness about homelessness and support available.

Building awareness across personnel and the public can increase self-identification and requests for

services. Increased general community awareness about homelessness and the resources available

under the MVHAA will allow the larger community to guide families that come into homelessness

to the appropriate and available resources.45 A crucial part of community awareness is educating the

public that being doubled-up with friends or family, due to loss of housing or economic hardship,

counts as being homeless and entitles families to MVHAA services and resources. Additionally,

public education must dispel the notion that there will be repercussions for disclosing one’s

homeless situation,46 in order to increase self-disclosure by families experiencing homelessness.

6) Increased educational support, especially for older youth.

Educational support to students experiencing homelessness is lacking in Rhode Island.

There needs to be stronger in-school and after-school educational support provided

to students experiencing homelessness. It is recommended that Rhode Island targets

educational services for students experiencing homelessness, including early childhood

education, before and after-school programs, mentoring, and summer programs. Older

youth experiencing homelessness may need additional services. In interviews with shelter

staff and families experiencing homelessness, it was found that youth in high school often

receive little help, contributing to many falling into “bad company” or dropping out.47

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 15

Conclusion ENDNOTES

1

McKinney Vento - Law in Practice; The McKinney Vento Act at a Glance.

The MVHAA has been an excellent addition to the (2008). National Center for Homeless Education. Retrieved from: https://

communications.madison.k12.wi.us/files/pubinfo/McKinneyV entoAtAGlance.

provision of services to Rhode Island‘s students who pdf

are experiencing homelessness. The identification of 2

United States Department of Education, 2018

students experiencing homelessness is a prevailing 3

Out of the Shadows: A State-by-State Ranking of Accountability for Homeless

Students, 2017. The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH).

challenge that LEAs across Rhode Island face, evident Retrieved from http://www.icphusa.org/ national/shadows-state-state-ranking-

accountability-homeless- students/

from how more than half of the parents interviewed

4

Wilson, Allison B., Squires, Jane, 2014 Young Children and Families

at shelters had no contact with a homeless education Experiencing Homelessness. Infants & Young Children Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 259–271

liaison. This is despite sheltered homeless families 5

Canfield, J. P., Harley, D., Teasley, M. L., & Nolan, J., 2017. Validating the

McKinney–Vento Act Implementation Scale: Examining the factor structure and

with school-aged children being the most visible of reliability. Children & Schools, 39(1), 53-60. doi:10.1093/cs/cdw047

this population. Resource constraints, compounded 6

United States Department of Education, 2016

by the lack of collaboration among homeless 7

Cunningham, M., Harwood, R., & Hall, S., 2010. Residential instability and the

McKinney-Vento Homeless Children and Education Program: What we know, plus

education liaisons, service providers, and the gaps in research. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

community, along with the weak accountability of 8

Wilson, Allison B., Squires, Jane, 2014 Young Children and Families

Experiencing Homelessness. Infants & Young Children Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 259–271

homeless education liaisons and enforcement of the

9

A Local Education Agency (LEA) is a public board of education or other public

MVHAA, contribute to the poor identification of and authority legally constituted within a State to provide administrative control or

a service for public elementary or secondary schools in a city, county, township,

support for students experiencing homelessness. school district, or other political subdivision of a State.

10

Canfield, J. P., Harley, D., Teasley, M. L., & Nolan, J., 2017. Validating the

McKinney–Vento Act Implementation Scale: Examining the factor structure and

However, families identified by homeless education reliability. Children & Schools, 39(1), 53-60. doi:10.1093/cs/cdw047

liaisons generally experienced few problems trying 11

United States Department of Education Fact Sheet: Supporting the Success of

Homeless Children and Youths, July 27, 2016. Also see https://naehcy.org/essa-

to obtain MVHAA services, such as intra-LEA implementation-best-practice-and-other-technical-assistance-tools/

transportation and getting school supplies. Yet, few Miller, P. M., 2013. Educating (More and More) Students Experiencing

12

Homelessness: An Analysis of Recession-Era Policy and Practice. Educational

students experiencing homelessness received extra Policy, 27(5), 805-838.

educational support under the MVHAA, especially older 2017 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook, 2017. Rhode Island KIDS COUNT.

13

Retrieved from http:// www.rikidscount.org/Portals/0/Uploads/Documents/

youth. The lack of educational support that children and Factbook%202017/2017%20R I%20Kids%20Count%20Factbook%20for%20

website.pdf

youth experiencing homelessness receive contributes

14

According to the MVHAA, a doubled-up family is defined as “sharing the

to some homeless students falling behind in school and housing of other persons due to loss of housing, economic hardship, or a similar

reason.”

consequently losing motivation and dropping out.

15

Hallett, R. E, Skrla, L, & Low, J., 2015. That is not what homeless is: a school

district’s journey toward serving homeless, doubled-up, and economically

displaced children and youth. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in

Education, 28:6, 671-692

16

National Health Care for the Homeless Council, What is the official definition

of homelessness? Retrieved from https://www.nhchc.org/faq/official-definition-

homelessness/

17

Out of the Shadows: A State-by-State Ranking of Accountability for Homeless

Students, 2017. The Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness (ICPH).

Retrieved from http://www.icphusa.org/ national/shadows-state-state-ranking-

accountability-homeless- students/

16 HousingWorks RI Scholar Series

18

U.S. Department of Education, 2015 33

Wilkins, T. B., Mullins, M. H., Mahan, A., & Canfield, J. P., 2016.

Homeless Education homeless liaisons’ Awareness about the

19

Out of the Shadows: A State-by-State Ranking of Accountability Implementation of the McKinney--Vento Act. Children & Schools, 38(1),

for Homeless Students, 2017. The Institute for Children, Poverty, 57-64. doi:10.1093/ cs/cdv041

and Homelessness (ICPH). Retrieved from http://www.icphusa.org/

national/shadows-state-state-ranking-accountability-homeless- 34

Canfield, J. P., Teasley, M. L., Abell, N., & Randolph, K. A., 2012.

students/ Validation of a McKinney- Vento Act Implementation Scale. Research

on Social Work Practice, 22, 410–419.

20

Tolbert, Janice, 2017 How Can Schools Provide Homeless Students

with Emotional and Behavioral Support? – Institute for Children, 35

Ibid.

Poverty & Homelessness. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.icphusa.org/

blog/can-schools-provide-homeless-students-emotional-behavioral- 36

Wilkins, T. B., Mullins, M. H., Mahan, A., & Canfield, J. P., 2016.

support/. Homeless Education homeless liaisons’ Awareness about the

Implementation of the McKinney--Vento Act. Children & Schools, 38(1),

21

Out of the Shadows: A State-by-State Ranking of Accountability 57-64. doi:10.1093/ cs/cdv041

for Homeless Students, 2017. The Institute for Children, Poverty,

and Homelessness (ICPH). Retrieved from http://www.icphusa.org/ 37

Hallett, R. E, Skrla, L, & Low, J., 2015. That is not what homeless is:

national/shadows-state-state-ranking-accountability-homeless- a school district’s journey toward serving homeless, doubled-up, and

students/ economically displaced children and youth. International Journal of

Qualitative Studies in Education, 28:6, 671-692

22

National Center for Homeless Education, 2009. Consolidated

State Profile. Retrieved from http:// profiles.nche.seiservices.com/ 38

Wilkins, T. B., Mullins, M. H., Mahan, A., & Canfield, J. P., 2016.

ConsolidatedStateProfile.aspx Homeless Education homeless liaisons’ Awareness about the

Implementation of the McKinney--Vento Act. Children & Schools, 38(1),

23

This figure is calculated by taking 0.203*19432 = 3945 (rounded up to 57-64. doi:10.1093/ cs/cdv041

the nearest whole number).

Wixom, M. A., 2016 State and Federal Policy: Homeless youth.

39

2017 Rhode Island Kids Count Factbook, 2017. Rhode Island KIDS

24

Education Commission of the States.

COUNT. Retrieved from http://www.rikidscount.org/Portals/0/

Uploads/Documents/Factbook%202017/2017%20RI%20Kids%20 40

Personal communication, education homeless liaison, January 12,

Count%20Factbook%20for%20website.pdf 2018.

25

2017 Housing Fact Book, 2017. Housing Works RI. Retrieved 41

Tanabe, C. S., & Mobley, I. H., 2011. The Forgotten Students: The

from https://www.housingworksri.org/ Portals/0/Uploads/ Implications of Federal Homeless Education Policy for Children in

Documents/2017_Housing%20Fact% 20Book.pdf Hawaii. Brigham Young University Education & Law Journal, 2011(1),

51-74.

26

For the mobility of homeless students, data was received from RIDE,

which gave every student who switched schools an exit code. Exit 42

As referenced in the earlier chapters in my thesis, the ranking of

codes 1-12, list “the circumstances under which the student exited from states was done by the Institute for Children, Poverty and Homelessness

membership in an educational institution” RIDE, 2017. However, in in the 2017 Out of the Shadows: A State-by-State Ranking of

the dataset used for this research, only exit codes 1-3 where recorded, Accountability for Homeless Students report.

which are for transfers to public schools in the same LEA, a different

LEA, or a different state, respectively. 43

As referenced in the earlier chapters in my thesis, the ranking of

states was done by the Institute for Children, Poverty and Homelessness

27

Rhode Island Kids Count, 2015 in the 2017 Out of the Shadows: A State-by-State Ranking of

Accountability for Homeless Students report.

28

Rhode Island Kids Count, 2017

44

Personal communication, Jennifer Barrera, Program Director at

29

Bradley, Anthony. “Rhode Island Makes It Difficult to Suspend Lucy’s Hearth, April 3, 2018.

Students.” Acton Institute PowerBlog. September 21, 2016. Retrieved

April 11, 2018. http://blog.acton.org/archives/89089-rhode-island- 45

Personal communication, education homeless liaison, January 18,

makes-it-difficult-to-suspend-students.html. 2018.

30

National Association for the Education of Homeless Children and 46

Anzilotti, E., 2016, September 29). What it Will Take to Keep

Youth; Authorization and Funding History of the McKinney-Vento Act’s Homeless Students in School. Retrieved from https://www.citylab.com/

Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program, 2016. Schoolhouse equity/2016/09/homeless-students-school-every- student-succeeds-

Connection. Retrieved from https://www.schoolhouseconnection.org/ act/502046/

wp-content/uploads/ 2016/12/mvhistory.pdf

Personal communication, Angela Ferrara, Crossroads Family Shelter

47

31

Hallett, R. E, Skrla, L, & Low, J., 2015. That is not what homeless is: Case Manager, January 30, 2018.

a school district’s journey toward serving homeless, doubled-up, and

economically displaced children and youth. International Journal of

Qualitative Studies in Education, 28:6, 671-692

Wixom, M. A., 2016 State and Federal Policy: Homeless youth.

32

Education Commission of the States. 7

HousingWorks RI Scholar Series 17

SCHOLAR SERIES One Empire Plaza

Providence, Rhode Island 02903

Contemporary Issues in Housing www.HousingWorksRI.org

Design: Lakuna Design

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Emergency HousingDocumento6 páginasEmergency HousingCheryl WestAinda não há avaliações

- Keeping Foster Youth Off The Streets: Improving Housing Outcomes For Youth That Age Out of Care in New York City,"Documento63 páginasKeeping Foster Youth Off The Streets: Improving Housing Outcomes For Youth That Age Out of Care in New York City,"Noah FranklinAinda não há avaliações

- Denver Emergency Operations Center April 4, 2020 Situation ReportDocumento9 páginasDenver Emergency Operations Center April 4, 2020 Situation ReportMichael_Roberts2019Ainda não há avaliações

- Rough Living An Urban Survival Manual Chris DamitioDocumento174 páginasRough Living An Urban Survival Manual Chris DamitioMike Nichlos100% (4)

- STARLIGHT8wbk RevisionDocumento18 páginasSTARLIGHT8wbk RevisionAnonymous vMEwCRl9G100% (2)

- Providence Water Bilateral Compliance Agreement 2019Documento5 páginasProvidence Water Bilateral Compliance Agreement 2019Anthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Resolution in Support of Free Enterprise and The Right To WorshipDocumento2 páginasResolution in Support of Free Enterprise and The Right To WorshipAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Business Guidlines HighlightsDocumento1 páginaBusiness Guidlines HighlightsAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Rhode Island High School Graduation Ceremony OptionsDocumento2 páginasRhode Island High School Graduation Ceremony OptionsAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Executive OrderDocumento3 páginasExecutive OrderAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- RI-General Business Organization GuidanceDocumento8 páginasRI-General Business Organization GuidanceAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- FY 2020 Monthly and YTD Revenue Assessment Report April 2020Documento20 páginasFY 2020 Monthly and YTD Revenue Assessment Report April 2020Anthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- RI Coalition of Wedding Vendors LetterDocumento14 páginasRI Coalition of Wedding Vendors LetterAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Viveiros Resignation LetterDocumento2 páginasViveiros Resignation LetterAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Executive Order Face MasksDocumento3 páginasExecutive Order Face MasksAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- RI Coalition of Wedding Vendors LetterDocumento14 páginasRI Coalition of Wedding Vendors LetterAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Flood ApDocumento62 páginasFlood ApAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- COVID-19 Fact SheetDocumento2 páginasCOVID-19 Fact SheetAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- RI Coalition of Wedding Vendors LetterDocumento14 páginasRI Coalition of Wedding Vendors LetterAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Flood ApDocumento62 páginasFlood ApAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- 2019 Factbook Final PDFDocumento193 páginas2019 Factbook Final PDFAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Flood ApDocumento62 páginasFlood ApAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Twin River Financials PDFDocumento13 páginasTwin River Financials PDFAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Barrington v. StudentDocumento5 páginasBarrington v. StudentAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Twin River Financials PDFDocumento13 páginasTwin River Financials PDFAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Second Incident in Pine HallDocumento1 páginaSecond Incident in Pine HallAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- School Removals Procedures Requirements PDFDocumento2 páginasSchool Removals Procedures Requirements PDFAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Columbus Statute ResolutionDocumento1 páginaColumbus Statute ResolutionAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Update Recent Campus Bias IncidentsDocumento2 páginasUpdate Recent Campus Bias IncidentsAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Verified ComplaintDocumento6 páginasVerified ComplaintAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- PPSD Organizational ChartDocumento1 páginaPPSD Organizational ChartAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Barrington Public Schools Statement Regarding BPS Vs Council...Documento3 páginasBarrington Public Schools Statement Regarding BPS Vs Council...Anthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- School Removals Procedures Requirements PDFDocumento2 páginasSchool Removals Procedures Requirements PDFAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- School Removals Procedures Requirements PDFDocumento2 páginasSchool Removals Procedures Requirements PDFAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Burrillville School Committee LetterDocumento2 páginasBurrillville School Committee LetterAnthony VegaAinda não há avaliações

- Oahu Point-in-Time Homeless CountDocumento25 páginasOahu Point-in-Time Homeless CountHNN100% (1)

- Olympia - Housing Options OrdinanceDocumento47 páginasOlympia - Housing Options OrdinanceThe UrbanistAinda não há avaliações

- Violence Homeless WomenDocumento103 páginasViolence Homeless WomenCristina Semi100% (1)

- Missouri Homelessness Study - Final Draft - 10.28.19Documento115 páginasMissouri Homelessness Study - Final Draft - 10.28.19KaitlynSchallhorn0% (1)

- Homelessness Research PaperDocumento2 páginasHomelessness Research Paperapi-509652744Ainda não há avaliações

- Sample MOUDocumento8 páginasSample MOUVikas RupareliaAinda não há avaliações

- CEO Response To The City of Dallas Audit of Homeless Response System EffectivenessDocumento9 páginasCEO Response To The City of Dallas Audit of Homeless Response System Effectivenesswfaachannel8Ainda não há avaliações

- Benefits of Enabled Gardening - Gardening For The HomelessDocumento5 páginasBenefits of Enabled Gardening - Gardening For The HomelessNeroulidi854Ainda não há avaliações

- Community Resource Guide: Housing, Food, Education & MoreDocumento47 páginasCommunity Resource Guide: Housing, Food, Education & Moresamu2-4u0% (1)

- Sacramento City Homeless Policy and Program OptionsDocumento57 páginasSacramento City Homeless Policy and Program OptionsCapital Public RadioAinda não há avaliações

- Long Term Effects of Homelessness On ChildrenDocumento28 páginasLong Term Effects of Homelessness On ChildrenandlyubvAinda não há avaliações

- 2009 Annual ReportDocumento30 páginas2009 Annual ReportHeather Brown HopkinsAinda não há avaliações

- Veterans and HomelessnessDocumento45 páginasVeterans and HomelessnessWane WolcottAinda não há avaliações

- Refelction IVDocumento1 páginaRefelction IVapi-318893345100% (1)

- Gaining Ground Pilot Project NarrativeDocumento22 páginasGaining Ground Pilot Project NarrativeCity Limits (New York)Ainda não há avaliações

- Homeless Emergency Solutions Grant ApplicationDocumento17 páginasHomeless Emergency Solutions Grant ApplicationBridgeportCTAinda não há avaliações

- ANALYSIS OF MASTER PLAN DELHI-2021w.r.tDocumento41 páginasANALYSIS OF MASTER PLAN DELHI-2021w.r.tSmriti SAinda não há avaliações

- 6.social Worker CV TemplateDocumento3 páginas6.social Worker CV TemplatePrabath DanansuriyaAinda não há avaliações

- Homeless Shelter Planning Effects On The Public's Sense of PlaceDocumento35 páginasHomeless Shelter Planning Effects On The Public's Sense of Placeapi-251312018Ainda não há avaliações

- Duval Epi Aid Trip ReportDocumento25 páginasDuval Epi Aid Trip ReportThe Florida Times-UnionAinda não há avaliações

- Social Service ResourcesDocumento2 páginasSocial Service Resourcesapi-294634156Ainda não há avaliações

- Homeless Person's Bill of Rights and Fairness ActDocumento31 páginasHomeless Person's Bill of Rights and Fairness ActDowning Post NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Geography of The Homeless Shelter PDFDocumento40 páginasGeography of The Homeless Shelter PDFChester ArcillaAinda não há avaliações

- Homeless Resource Center and Homeless Shelter Information SheetDocumento17 páginasHomeless Resource Center and Homeless Shelter Information SheetThe Salt Lake TribuneAinda não há avaliações

- Caroline's ResumeDocumento2 páginasCaroline's ResumeckiharaAinda não há avaliações