Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Chinese Botanical Drawings - Reeves Collection - RHS - Plantsman 2010

Enviado por

Mervi Hjelmroos-KoskiTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Chinese Botanical Drawings - Reeves Collection - RHS - Plantsman 2010

Enviado por

Mervi Hjelmroos-KoskiDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

botanical art

The Reeves Collection

of Chinese botanical drawings

Having recently completed a three-year conservation research

project on the collection, Kate Bailey describes an outstanding

collection of early 19th-century art held at the RHS Lindley Library

218 December 2010

Plantsman

The

W

hen Robert Fortune of sending information to the great undertook some preparatory work:

embarked on his first man, Banks himself held Reeves in the East India Company’s records

trip to China in 1843, high regard. To Banks he sent show that he had copies made of the

he had been well briefed by an samples of teas, bird’s nests and Chinese flower paintings held at East

active member of the Horticultural information about horn lantern- India House in Leadenhall Street,

Society’s Chinese Committee, John making, Chinese deities, plants, oils London, and it would seem that he

Reeves. Reeves referred him to a set and much else. also procured collectors’ seals for

of coloured drawings which he had The East India Company’s tea the Society and for himself. The

sent back from Canton to the trade with China was based at Society’s seal comprised the letters

Society some years earlier. These Canton, on the north bank of the ‘HS’ and a cartouche within which

watercolours, now known as the Pearl River. Other commodities Reeves could ink in the number of

Reeves Collection, are bound into were also traded, either by the the drawing.

eight albums and are held at the RHS Company itself, or by its senior Reeves must have been prompt in

Lindley Library where they have been officers who were permitted to carry appointing his first painter, whom

the subject of a conservation research on ‘private trade’. Westerners were Joseph Sabine described as ‘one of

project over the last three years. unwelcome, being disparagingly the best native artists’. The Society’s

referred to as fan qui (foreign devils) minutes (Anon. 1817–31, 1815–24)

John Reeves and the East by the Chinese, and the government can be read together to build up

India Company restricted their movement. During an early record of the making of

John Reeves (1774–1856) was born in the winter months, ‘the tea season’, the Collection. Twenty-nine

West Ham, London, the youngest employees stayed at the Company’s commissioned pictures had been

son of a clergyman. Leaving Christ’s factory, a series of connected received by 7 July 1818, and by April

Hospital school at the age of 15, buildings comprising warehouses, 1820 this number had increased to

Reeves took up an apprenticeship offices, bedrooms, dining room 81. A further report to the Drawings

with a London tea broker, Richard and library. The only permitted Committee for 25 April 1822 shows

Pinchback. He then joined the East excursions were to Honam Island that the figure had risen to 138, with

India Company as a tea inspector in and the Fa-Tee (flowery land) 52 separate Chinese drawings.

London. In 1803 he married Sarah nurseries on the opposite bank.

Russell with whom he had four The summer months, from about Two types of picture

children, but in 1810 Sarah died. March to October, depending on These minutes indicate that two

Whether her death prompted sailing conditions, were spent types of picture were being sent back.

Reeves to consider a career move is 100km down river at Macao where The commissioned paintings were

not known, but in 1811 he was European and American traders executed on thick, cream English

appointed assistant tea inspector for were allowed rather more freedom. watercolour paper, predominantly

Canton and started to learn Chinese. produced by Whatman and made

Prior to sailing in 1812, Reeves was Making the Collection from cotton rag, measuring at least

introduced to Sir Joseph Banks by In 1816–17, Reeves returned home 48 x 36cm. These bear the Society’s

his first cousin, a prominent barrister, to work in London temporarily. seal, and most also show the Chinese

confusingly also named John Reeves. The Horticultural Society’s minutes plant name, written in Chinese

Although the details of that meeting of Council (Anon. 1817-31) record: characters in Chinese ink. The

were not recorded, it is obvious from ‘That the proposal of John Reeves painting of Paris polyphylla (p220)

the ensuing correspondence that Esq. to send plants and drawings shows a typical layout of these

Banks appointed Reeves to be one from China, for the use of the sheets; in this instance the Chinese

of his many collectors. From letters I Society, be accepted with thanks – characters for the plant name are

have traced in several institutions, it and that the Secretary do offer to accompanied by a transliteration

is clear that although Reeves was Mr. Reeves the advance of such which gives their sounds in Canton

somewhat daunted at the prospect sums as he may require towards the ese. Although many of Reeves’s

cost of the same.’ numbers were trimmed away during

A painting of a double-flowered cultivar

Reeves became a corresponding binding it has been possible to

of Hemerocallis fulva demonstrates the member and the Society arranged partially re-create his original

realism of some of the Reeves paintings for the payment of his expenses. He painting order. However, a few of ➤

December 2010 219

botanical art

Features of the Collection

The Reeves Collection is perhaps

unique in a number of respects.

Although other collections of

Chinese botanical work are held

privately, and in public institutions

such as Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew,

their provenance is not recorded in

the same detail as it is with the

Reeves pictures. The numbers on

the paintings, where they exist, can

be compared with the Society

minutes and, by a process of simple

deduction, it is possible to determine

which paintings were sent back in

the early or later batches. This

information can be corroborated

by dated watermarks in the papers.

Furthermore, almost all the

pictures, fans and wallpapers which

formed part of the export art trade

in the 19th century were produced

by men who remained anonymous.

The Chinese regarded these items as

commercial products rather than art,

and their creators as tradesmen rather

than artists. It is therefore very

unusual to be able to match named

painters to a collection. The Reeves

Collection is a notable exception.

Two of Reeves’s 1829 notebooks

survive at the Natural History

Museum, London. These principally

This painting of Paris polyphylla shows damaged foliage and paler undersides to the leaves, techniques record the making of a collection of

derived from adherence to painting the true nature of the subject fish paintings for Major-General

these paintings formed separate sub- and the Society’s second gardener, Thomas Hardwicke, but also a few

sets. The series of Camellia pictures, John Damper Parks, who joined plant paintings. Four artists’ names

for example, were given their own Reeves in 1823, noted: are given – Akew, Akam, Akut and

discrete numbering system, possibly ‘Nov. 20 1823. A Camellia which Asung, with records of payments

because there was a great deal of is scarce at Canton…It has flowered. made to each. The prefix ‘A’ or ‘Ah’

interest in the introduction of these I have seen a drawing of [it] with in Cantonese denoted a person of

and many were similar in appearance. Mr. Reeves.’ low social status, such as a servant.

It is likely that these pictures were The second type of picture was From the notebooks it has been

sent back early on because John small, purchased works painted on estimated that each man produced

Potts, the Society’s gardener sent out fine, almost transparent, white about one picture per day and was

to China to collect in 1821, made Chinese papers made from mixed paid one dollar, in the contemporary

reference to camellias in his diaries fibres, including rice straw. These currency, for three paintings.

(Potts 1821, rough journal): pictures, such as of Callicarpa From close scrutiny of the 900 or

‘Dec.11. Packing some boxes of bodinieri (p221), which were not so pictures at the Lindley Library I

plants, received some Camellias inscribed in Chinese, were sent to have been able to discern Reeves’s

from Macao…’ the Society on approval. notes of the names of three of these

220 December 2010

About 35 paintings of Camellia were sent back;

these were particularly valued because of the

potential for introduction of new cultivars.

The painting of Callicarpa bodinieri is typical of the

purchased works done on Chinese paper

painters, with dates. This confirms

that he was using the same artists for

fish and flower painting, and that he

employed them over a period of 12

years. From the dates given, and

known flowering times, it is almost

certain that much of the painting

was carried out during the summer

months in Macao.

The notebooks also serve to

confirm that Reeves was keeping a

watchful eye over the painting

process. He may have needed to do

so. In his obituary in the Gardeners’

Chronicle and Agricultural Gazette (29

March 1856) it was stated that the

drawings were ‘executed in his own

house, under his own superint

endence, in order to secure himself

against the deceptions practiced by

the native draughtsmen’. John

Barrow (1806) noted that it was not

unknown in pictures ‘to meet ➤

December 2010 221

botanical art

Chinese and Western flower

painting traditions

The two types of picture in the

Collection emphasize the

differences between Chinese and

Western flower painting traditions.

The smaller pictures on the Chinese

papers are typically Chinese, with

traditional pigments such as

vermilion, yellow gamboge and blue

azurite being laid down in thin

washes with no visible under-

drawing. This was achieved using a

fine brush and well-diluted ink, so

that the watery lines would have

disappeared beneath the painted

areas. The detail is exquisite and the

overall effect is one of brightness and

transparency.

In contrast, the paintings on the

Western papers represent a fusion

of Western and Chinese painting

methods. Many include separately

drawn flower parts, as an aid to

classification and identification in

accordance with the principles of

Linnaean taxonomy. Graphite

under-drawing can be readily seen,

and the paint has been applied more

thickly in layers, often as a gouache.

This has produced an opaque effect.

Unlike the smaller pictures, which

Clerodendrum bungei, demonstrating the realism of damaged foliage and paler undersides to the leaves would have been repeatedly dipped

in an alum solution to fix the colours,

with the flower of one plant set upon translations of such exotic names as the artists would have been unable to

the stalk of another, and having the ‘purple pheasant’s tail’, ‘yellow do this with the thicker papers. This,

leaves of a third’. The intention, golden thread’ and ‘egg-yellow globe’ and the breakdown of the paint

perhaps, was not necessarily to for some of the chrysanthemums, binder, may account for the green

deceive but merely to produce formed the basis of a series of articles malachite flaking from the surface of

colourful pictures to boost sales to by Joseph Sabine and John Lindley in painted leaf and stem areas in some

foreigners. the Society’s Transactions. Not only of the pictures.

The close supervision paid were the drawings used for research A further problem, more

dividends. Joseph Sabine (1824) and to verify the names of live noticeable on the larger drawings

commented that ‘Of the correctness specimens, but they could also be and particularly the pictures of

of these drawings I have little used for comparative purposes. camellias, is the darkening of lead

doubt…’. The need for such accuracy Sabine, for example, concluded that white and red lead. This has been

is obvious. These drawings were, in differences in appearance between caused by sulphur dioxide, an

effect, a plant catalogue used by the the plants in the drawings and atmospheric pollutant often

Society to order live specimens from those grown in England might be associated with coal-burning, which

Reeves. The supporting information attributable to different gardening has reacted with the lead carbonate

provided by him, including techniques. to produce lead sulphide.

222 December 2010

Plantsman

The

Portion of one of the Camellia paintings showing

restoration of the lead white which had turned

to black lead sulphide as a result of sulphur

dioxide pollution

Both types of painting faithfully

portray diseased and insect-damaged

leaves and the pale undersides of

foliage. The illustrations of

Clerodendrum bungei (p222) and Paris

polyphylla (p220) are good examples

of both these techniques. This

practice was probably derived from

Chinese instructional texts that

taught the importance of painting

the true nature of the subject. In

many instances, white petals were

surrounded with a grey-blue wash to

make them stand out from the

paper, as in the illustration of Hosta

plantaginea (p224). These

characteristics are all typical of

Chinese painting method.

Foreshortening was not usually

adopted, and shading, if any, tended

to be achieved by gradations of a

single colour. This was made

possible by grinding the mineral

pigments, particularly malachite, to

varying degrees of fineness: the

smaller the individual crystals, the

paler the shade.

Later history of the drawings

During the 1820s the Horticultural

Society faced increasing financial

difficulties. This resulted in Reeves

being requested to cease his

collecting activities, and led to the

disposal of unwanted drawings. In

1859, three years after Reeves’s

death, the Society’s entire library,

including the Reeves albums, was

auctioned off. However, by a set of

fortuitous circumstances, five

Reeves albums came back to the

Society in 1936 through a bequest by

horticulturist and coal magnate

Reginald Cory. He had bought them

from a bookseller in 1908 and he left

his library to the Society after his

Two Chrysanthemum cultivars with their Chinese names and transliterations death in 1934. In 1953, three ➤

December 2010 223

botanical art

This illustration of Hosta plantaginea shows the

grey-blue wash used by the Chinese artists to

highlight white flowers

more albums came to the Society’s

notice and these were purchased

with funds derived from the Cory

bequest. As a result, nearly all the

Reeves drawings that were sold in

1859 are now back in the Society’s

possession.

Conservation research

One of the purposes of my research

has been to identify the best

conservation treatments for these

pictures. The papers in the five

smaller albums have suffered water

damage during the period of private

ownership which has resulted in

discoloration, tide-lines and some

mould damage, in addition to the

pigment changes referred to above.

The Chinese papers were adhered

with animal glue to 1837 Whatman

papers, presumably during the

binding process. This has caused

unsightly brown patches and severe

creasing at the corners, some of

references which have become detached.

Anon. (1815–1824) Minutes of the Society at Chiswick, from its first One volume has already been

Drawings Committee of the formation to March 1826. Trans. Hort. disbound and the intention is to

Horticultural Society of London Soc. Lond. 7: 239 disbind the others with a view to

Anon. (1817–1831) Minutes of Council Parks, JD (1823) Rough Journal. Unpub returning the drawings to their

of the Horticultural Society of London lished, held at RHS Lindley Library original format as individual sheets.

2–10 Potts, J (1821) Fair Journal. Unpub

Anon. (1856) Obituary: John Reeves. lished, held at RHS Lindley Library I collected tiny fragments of

The Gardeners’ Chronicle and Agricultural Potts, J (1821) Rough Journal. Unpub pigment trapped at the spine edges

Gazette: 29 March lished, held at RHS Lindley Library and these are the subject of on-going

Barrow, J (1806) Travels in China. Reeves, J (1829) China Fishes. pigment identification using light

T Cadell and W Davies, London Unpublished, held at Natural History microscopy and chemical tests.

Bretschneider, É (1898) History Museum Although inorganic pigments can

of European Botanical Discoveries Reeves, J (1829) Chinese Fish. be readily identified using these

in China. Sampson Low, Marston Unpublished, held at Natural History

methods, I have established that

& Co., London Museum

Lindley, J (1826) Report upon the Sabine, J (1824 ) Account and descript some of the pigments, including

new or rare plants which have flowered ion of five new Chinese chrysanthemums; several reds, are organic. It is hoped

in the garden of the Horticultural with some observations on the treatment that these can be identified using

Society at Chiswick, from its first of all the kinds at present cultivated in Raman spectroscopy (a type of laser

formation to March 1824. Trans. Hort. England, and on other circumstances analysis) so that a more comprehen

Soc. Lond. 6: 80 relating to the varieties generally. sive list of the pigments used in

Lindley, J (1830) Report upon the Trans. Hort. Soc. Lond. 5: 425

Canton at this period can be

new or rare plants which have flowered Sabine, J (1826) On Glycine sinensis.

in the garden of the Horticultural Trans. Hort. Soc. Lond. 7: 460 compiled. This will be a valuable

resource for future researchers.

224 December 2010

Plantsman

The

John Reeves’s contribution to

horticulture

There is no indication in the Society’s

minutes, or in the journals of its

gardeners, of the difficulties Reeves

encountered in sending plants to

England, but his letters are revealing.

Firstly, the physical restrictions

imposed by ‘the villainous govern

ment of this vile country’ meant that

he was largely reliant upon Chinese

collectors. In 1830 he wrote to

Lindley that ‘the Chinese collectors

have tried my patience out over and

over again’. Secondly, he was

frustrated at Chinese gardeners who

considered his potted specimens of

wild flowers to be weeds and

therefore not worthy of cultivation.

Finally, he re-potted several hundred

plants with suitable loam and packed

them into wooden crates for

shipment. But many were lost

overboard, neglected during transit

or died from the extreme conditions

associated with crossing the equator.

Despite these difficulties, John

Reeves is credited with the intro

duction of many fine azaleas,

camellias, chrysanthemums and

moutan peonies, many of which are

represented in the drawings. These

were the subject of several papers Wisteria sinensis, a plant associated with Reeves, though not introduced by him

presented to the Horticultural

Society by John Lindley and Joseph obituary that ‘Not a Company’s ship Conclusion

Sabine. Reevesia thyrsoidea was named at that time sailed for Europe without The Reeves drawings were said by

in his honour by Lindley. Émile her decks being decorated with the Bretschneider to be ‘by far the most

Bretschneider listed nearly 50 plants little portable greenhouses …’. extensive in Europe’. Much inform

as Reeves’s introductions, including Reeves’ name is particularly ation about them has come to light

Astranthus cochinchinensis, associated with two well-known as a result of my research. Following

Clerodendrum canescens, Photinia garden plants: Primula sinensis, which conservation treatment, these

prunifolia and Prunus serrulata. So he certainly introduced, and Wisteria pictures will once again be a working

industrious was Reeves, that it was sinensis, which he did not. The first collection, capable of being used for

reported in the Gardeners’ Chronicle Wisteria sinensis was brought to research purposes, as Reeves and the

England by Captain Robert Welbank Society originally intended.

conservation funding

of the East India Company in 1816,

The Reeves Collection is being but Reeves did send back a fine Kate Bailey is completing a

conserved and digitised with the specimen, given to him by Consequa, PhD (funded by the Finnis Scott

generous support of the KT Wong one of the Cantonese merchants, Foundation and the RHS) at

Foundation. It is anticipated that

which flourished in the Society’s the Conservation Department,

the work will take three years.

garden in Chiswick for many years. Camberwell College of Arts, London

December 2010 225

Você também pode gostar

- Plant and Floral Studies for Artists and CraftspeopleNo EverandPlant and Floral Studies for Artists and CraftspeopleAinda não há avaliações

- Botanical Illustration, January - June 2009Documento14 páginasBotanical Illustration, January - June 2009Mervi Hjelmroos-Koski78% (9)

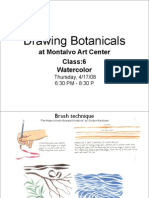

- Drawing Botanicals, Class 6 :: WatercolorDocumento13 páginasDrawing Botanicals, Class 6 :: Watercolormontalvoarts92% (24)

- Illustrating Nature: How to Paint and Draw Plants and AnimalsNo EverandIllustrating Nature: How to Paint and Draw Plants and AnimalsNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)

- Kirstenbosch Botanical Art Biennale 2010Documento19 páginasKirstenbosch Botanical Art Biennale 2010Art Times79% (14)

- 2012 Summer - Fall Distance Learning Program For Denver Botanic Gardens' Botanical Art and Illustration ProgramDocumento10 páginas2012 Summer - Fall Distance Learning Program For Denver Botanic Gardens' Botanical Art and Illustration ProgramMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Theorem Painting: Tips, Tools, and Techniques for Learning the CraftNo EverandTheorem Painting: Tips, Tools, and Techniques for Learning the CraftAinda não há avaliações

- An Eye For DetailDocumento17 páginasAn Eye For DetailMervi Hjelmroos-Koski83% (6)

- Botanical DrawingDocumento14 páginasBotanical Drawingcrackle123100% (7)

- The Art of Abc: Chinese Brush Paintings for All AgesNo EverandThe Art of Abc: Chinese Brush Paintings for All AgesAinda não há avaliações

- Drawing Botanicals, Class 1 :: DrawingDocumento114 páginasDrawing Botanicals, Class 1 :: Drawingmontalvoarts95% (21)

- Drawing Botanicals, Class 3 :: PenDocumento44 páginasDrawing Botanicals, Class 3 :: Penmontalvoarts100% (15)

- Botanical Illustration: The Essential ReferenceNo EverandBotanical Illustration: The Essential ReferenceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (10)

- 2012 - Spring Botanical Illustration Distance Learning Program at Denver Botanic GardensDocumento11 páginas2012 - Spring Botanical Illustration Distance Learning Program at Denver Botanic GardensMervi Hjelmroos-Koski100% (2)

- Wonderland Botanical Illustration GuideDocumento15 páginasWonderland Botanical Illustration Guidekmd78100% (2)

- A Garden of Flowers: All 104 Engravings from the Hortus Floridus of 1614No EverandA Garden of Flowers: All 104 Engravings from the Hortus Floridus of 1614Ainda não há avaliações

- Drawing Botanicals, Class 5 :: ScratchboardDocumento15 páginasDrawing Botanicals, Class 5 :: Scratchboardmontalvoarts100% (3)

- Chinese Brush Painting: A Beginner's Step-by-Step GuideNo EverandChinese Brush Painting: A Beginner's Step-by-Step GuideNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- Botanical Art and Illustration - 2009 Summer - Fall CatalogDocumento13 páginasBotanical Art and Illustration - 2009 Summer - Fall CatalogMervi Hjelmroos-Koski60% (10)

- Crafting Modern Florals: Creating Botanical Patterns with Petals, Pencils & PaintNo EverandCrafting Modern Florals: Creating Botanical Patterns with Petals, Pencils & PaintNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Claudia Nice Exporing WatercolorDocumento19 páginasClaudia Nice Exporing WatercolorCosmin Tudor Ciocan62% (26)

- Botanical Illustration Certificate Program at Denver Botanic Gardens - Distance Learning Program Spring 2011Documento8 páginasBotanical Illustration Certificate Program at Denver Botanic Gardens - Distance Learning Program Spring 2011Mervi Hjelmroos-Koski100% (2)

- The Big Book of Painting Nature in Watercolor (1990) PDFDocumento400 páginasThe Big Book of Painting Nature in Watercolor (1990) PDFRicardo Almeida100% (21)

- Better Art Flowers 2015Documento116 páginasBetter Art Flowers 2015JuanRodriguez100% (12)

- Claudia Nice Painting Nature in Pen and Ink With WatercolorDocumento136 páginasClaudia Nice Painting Nature in Pen and Ink With WatercolorStaska Kolbaska95% (42)

- Botanical Art and Illustration 2010 Winter - Spring CatalogueDocumento14 páginasBotanical Art and Illustration 2010 Winter - Spring CatalogueMervi Hjelmroos-Koski100% (3)

- Contemporary Botanical Artists The Shirley Sherwood Collection PDFDocumento248 páginasContemporary Botanical Artists The Shirley Sherwood Collection PDFFacundo Soto100% (23)

- Drawing and WatercolourDocumento120 páginasDrawing and WatercolourVartikka Kaul100% (4)

- Botanical BooksDocumento1 páginaBotanical BooksKrzysztof KowalskiAinda não há avaliações

- Beginners Guide World of WatercolorDocumento27 páginasBeginners Guide World of WatercolorGesana Biti88% (8)

- Rules of Botanical DrawingDocumento16 páginasRules of Botanical DrawingAna Cláudia AlencarAinda não há avaliações

- Billy Showell - Billy Showell's Botanical Painting in Watercolour-Search Press (2016)Documento100 páginasBilly Showell - Billy Showell's Botanical Painting in Watercolour-Search Press (2016)Fatima Tanweer100% (26)

- Botanical Sketch Book PDFDocumento8 páginasBotanical Sketch Book PDFjoju053153% (32)

- Botanical Art and Illustration Certificate Program, Winter/Spring 2012 CatalogDocumento20 páginasBotanical Art and Illustration Certificate Program, Winter/Spring 2012 CatalogMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Lee J James Draw 50 Flowers Trees and Other Plants PDFDocumento52 páginasLee J James Draw 50 Flowers Trees and Other Plants PDFjoju053191% (23)

- Intro To Botanical ArtDocumento17 páginasIntro To Botanical ArtFaheemulHasan100% (5)

- Watercolor HighlightsDocumento2 páginasWatercolor HighlightsInterweave17% (6)

- Scientific IllustrationsDocumento11 páginasScientific Illustrationsalicia_called80% (5)

- Oriental Watercolor Techniques For Contemporary Painting PDFDocumento136 páginasOriental Watercolor Techniques For Contemporary Painting PDFelgreca100% (3)

- Watercolor TipsDocumento8 páginasWatercolor TipsIkram Iqram100% (8)

- Painting Nature in Pen Amp Amp Ink With Watercolo PDFDocumento136 páginasPainting Nature in Pen Amp Amp Ink With Watercolo PDFescala-mind100% (5)

- Best of Watercolor Painting Color PDFDocumento152 páginasBest of Watercolor Painting Color PDFAbdu Amenukal100% (1)

- Watercolor TocDocumento16 páginasWatercolor TocInterweave37% (19)

- Watercolor Artist - June 01 2019 PDFDocumento76 páginasWatercolor Artist - June 01 2019 PDFFelipe Jaramillo100% (5)

- Modern Watercolor - A Playful and Contemporary Exploration of Watercolor Painting PDFDocumento131 páginasModern Watercolor - A Playful and Contemporary Exploration of Watercolor Painting PDF214549 delgado97% (35)

- Beginners Guide To Botanical Flower Painting (Lakin, Michael)Documento67 páginasBeginners Guide To Botanical Flower Painting (Lakin, Michael)Álvaro MT100% (5)

- Adding Color Value - WatercolorDocumento8 páginasAdding Color Value - Watercolorapi-314366206Ainda não há avaliações

- Watercolour VademecumDocumento412 páginasWatercolour VademecumAlessioMas100% (5)

- The Art of Botanical & Bird Illustration - An Artist's Guide To Drawing and Illustrating Realistic Flora, Fauna, and Botanical Scenes From Nature - PDF RoomDocumento315 páginasThe Art of Botanical & Bird Illustration - An Artist's Guide To Drawing and Illustrating Realistic Flora, Fauna, and Botanical Scenes From Nature - PDF RoomJaime Coatzin100% (7)

- RBGE Certificate in Botanical Illustration 2015-2016Documento20 páginasRBGE Certificate in Botanical Illustration 2015-2016HipsipilasAinda não há avaliações

- Drawing Botanicals, Class 4 :: Ink WashDocumento26 páginasDrawing Botanicals, Class 4 :: Ink Washmontalvoarts100% (8)

- Chinese Watercolor Techniques F - Lian Quan ZhenDocumento136 páginasChinese Watercolor Techniques F - Lian Quan ZhenMaiAnhTa100% (3)

- Brush Strokes VocabularyDocumento6 páginasBrush Strokes VocabularyInthegoodmood Goodmood100% (11)

- Mediapedia Drawing PDFDocumento4 páginasMediapedia Drawing PDFJoe Dickson100% (1)

- DBG/GNSI Exhibit 2013-2014 - Save The Date InfoDocumento2 páginasDBG/GNSI Exhibit 2013-2014 - Save The Date InfoMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Entry Form - BI Show - DBG 2012Documento1 páginaEntry Form - BI Show - DBG 2012Mervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Contemporary Traditions - Call To ArtistsDocumento2 páginasContemporary Traditions - Call To ArtistsMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- DBG/GNSI Exhibit 2013-2014 - Save The Date InfoDocumento2 páginasDBG/GNSI Exhibit 2013-2014 - Save The Date InfoMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- 2012 Summer-Fall BI CatalogDocumento17 páginas2012 Summer-Fall BI CatalogMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Watercolor II Supply ListDocumento2 páginasWatercolor II Supply ListMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- One Big LeafDocumento2 páginasOne Big LeafMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Plants in Japanese PaperDocumento2 páginasPlants in Japanese PaperMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Entry Form - BI Show - Parker 2012Documento1 páginaEntry Form - BI Show - Parker 2012Mervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Watercolor Pencil IDocumento1 páginaWatercolor Pencil IMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Botanical Art and Illustration 2010 Winter - Spring CatalogueDocumento14 páginasBotanical Art and Illustration 2010 Winter - Spring CatalogueMervi Hjelmroos-Koski100% (3)

- Watercolor I Supply ListDocumento2 páginasWatercolor I Supply ListMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Watercolor Pencil IIDocumento2 páginasWatercolor Pencil IIMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Business of ArtDocumento1 páginaBusiness of ArtMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Watercolor Pencil IDocumento1 páginaWatercolor Pencil IMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Watercolor Pencil IIDocumento2 páginasWatercolor Pencil IIMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Spring Has SprungDocumento1 páginaSpring Has SprungMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Under The PressDocumento1 páginaUnder The PressMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- IntroductionDocumento1 páginaIntroductionMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Radiance in RealismDocumento1 páginaRadiance in RealismMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Surface TexturesDocumento2 páginasSurface TexturesMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- PerspectiveDocumento1 páginaPerspectiveMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Papermaking - P. BransteadDocumento1 páginaPapermaking - P. BransteadMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- One Big LeafDocumento2 páginasOne Big LeafMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Pen and Ink IIDocumento1 páginaPen and Ink IIMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Pencil IIDocumento1 páginaPencil IIMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Pencil IDocumento1 páginaPencil IMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Pen and Ink IDocumento2 páginasPen and Ink IMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Nature of Drawing Birds IIDocumento1 páginaNature of Drawing Birds IIMervi Hjelmroos-KoskiAinda não há avaliações

- Shaheen Fs OconnorDocumento21 páginasShaheen Fs OconnorNfr IbAinda não há avaliações

- Recoding The Museum: Digital Heritage and The Technologies of Change.Documento3 páginasRecoding The Museum: Digital Heritage and The Technologies of Change.Catedra Fácil Luis GmoAinda não há avaliações

- Al-Qods Al-Shareef: Shawqi Sha'thDocumento184 páginasAl-Qods Al-Shareef: Shawqi Sha'thludovic1970Ainda não há avaliações

- Panama Canal - HistoryDocumento1 páginaPanama Canal - HistoryFatima Nana-DegiaAinda não há avaliações

- Readings in Phil - History. MidtermDocumento5 páginasReadings in Phil - History. MidtermGilmer Bacani GamiloAinda não há avaliações

- Why Modernism Still MattersDocumento12 páginasWhy Modernism Still MattersPePé PameAinda não há avaliações

- The Mexican Revolution 1910-1940 - Philip Benson and Yvonne Berliner - Hodder 2013Documento241 páginasThe Mexican Revolution 1910-1940 - Philip Benson and Yvonne Berliner - Hodder 2013tecsen100% (2)

- All About History Book of The Tudors 2015 UKDocumento164 páginasAll About History Book of The Tudors 2015 UKmca201283% (6)

- Module 5 Doing History A Guide For StudentsDocumento6 páginasModule 5 Doing History A Guide For StudentsPrincess Vee ReyesAinda não há avaliações

- Introductory Petrography of FossilsDocumento313 páginasIntroductory Petrography of FossilsLuisMauricioValenzuelaAinda não há avaliações

- Still Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History, Volume 2 (1914 2006)Documento562 páginasStill Casting Shadows: A Shared Mosaic of U.S. History, Volume 2 (1914 2006)B. Clay ShannonAinda não há avaliações

- Aims Concepts of HistoryDocumento1 páginaAims Concepts of Historyapi-299452757Ainda não há avaliações

- Digital Unit Plan Template - Grade 7-Roman EmpireDocumento3 páginasDigital Unit Plan Template - Grade 7-Roman Empireapi-398444863Ainda não há avaliações

- A New Phase of Systematic Development of Scientific Theories in 2021Documento457 páginasA New Phase of Systematic Development of Scientific Theories in 2021salurAinda não há avaliações

- Eminent Domain & African Americans: What Is The Price of The Commons?Documento13 páginasEminent Domain & African Americans: What Is The Price of The Commons?Institute for JusticeAinda não há avaliações

- The History of English GrammarsDocumento134 páginasThe History of English GrammarsGulmaidan KhalidullinaAinda não há avaliações

- Building The Transcontinental RailroadDocumento8 páginasBuilding The Transcontinental RailroadEmily JiménezAinda não há avaliações

- Course Outline Readings in Philippine History Nu BaliwagDocumento6 páginasCourse Outline Readings in Philippine History Nu BaliwagFerdinand Dela CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Winfried Noth Handbook of Semiotics 1990Documento765 páginasWinfried Noth Handbook of Semiotics 1990Siarhej Sanko100% (2)

- 1911 FinalDocumento8 páginas1911 FinalArushi Jain100% (1)

- Rizal Morga, Luna & HidalgoDocumento13 páginasRizal Morga, Luna & HidalgoMarian PadillaAinda não há avaliações

- A Short History of Film Archiving: ......... BUFVCDocumento3 páginasA Short History of Film Archiving: ......... BUFVCSanjit Narwekar100% (1)

- Readings in Philippine HistoryDocumento15 páginasReadings in Philippine HistoryDahlia GalimbaAinda não há avaliações

- Historia de La HumanidadDocumento991 páginasHistoria de La HumanidadRaymundo LuchoAinda não há avaliações

- Charles de Harlez The Yih King 16pDocumento30 páginasCharles de Harlez The Yih King 16ptito19593100% (1)

- Report Writing Skills Project Report Artificial IntelligenceDocumento12 páginasReport Writing Skills Project Report Artificial IntelligenceKinza NisarAinda não há avaliações

- History Theme - IIDocumento157 páginasHistory Theme - IIKaushik SenguptaAinda não há avaliações

- Exposed Uncovered Declassified Lost Civilizations Secrets of The Past PDFDocumento225 páginasExposed Uncovered Declassified Lost Civilizations Secrets of The Past PDFNelson Alvarez100% (2)

- Frederick The GreatDocumento4 páginasFrederick The Greatguitar4001Ainda não há avaliações

- The House at Pooh Corner - Winnie-the-Pooh Book #4 - UnabridgedNo EverandThe House at Pooh Corner - Winnie-the-Pooh Book #4 - UnabridgedNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (5)

- The Encyclopedia of Spices & Herbs: An Essential Guide to the Flavors of the WorldNo EverandThe Encyclopedia of Spices & Herbs: An Essential Guide to the Flavors of the WorldNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (5)

- The Importance of Being Earnest: Classic Tales EditionNo EverandThe Importance of Being Earnest: Classic Tales EditionNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (44)

- You Can't Joke About That: Why Everything Is Funny, Nothing Is Sacred, and We're All in This TogetherNo EverandYou Can't Joke About That: Why Everything Is Funny, Nothing Is Sacred, and We're All in This TogetherAinda não há avaliações

- The Most Forbidden Knowledge: 151 Things NO ONE Should Know How to DoNo EverandThe Most Forbidden Knowledge: 151 Things NO ONE Should Know How to DoNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (6)

- Midwest-The Lost Book of Herbal Remedies, Unlock the Secrets of Natural Medicine at HomeNo EverandMidwest-The Lost Book of Herbal Remedies, Unlock the Secrets of Natural Medicine at HomeAinda não há avaliações

- Permaculture for the Rest of Us: Abundant Living on Less than an AcreNo EverandPermaculture for the Rest of Us: Abundant Living on Less than an AcreNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (33)

- Root to Leaf: A Southern Chef Cooks Through the SeasonsNo EverandRoot to Leaf: A Southern Chef Cooks Through the SeasonsNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)

- Soil: The Story of a Black Mother's GardenNo EverandSoil: The Story of a Black Mother's GardenNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (16)

- Square Foot Gardening: How To Grow Healthy Organic Vegetables The Easy WayNo EverandSquare Foot Gardening: How To Grow Healthy Organic Vegetables The Easy WayNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (3)

- A Girl and Her Greens: Hearty Meals from the GardenNo EverandA Girl and Her Greens: Hearty Meals from the GardenNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (7)

- The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They CommunicateNo EverandThe Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They CommunicateNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1003)

- Welcome to the United States of Anxiety: Observations from a Reforming NeuroticNo EverandWelcome to the United States of Anxiety: Observations from a Reforming NeuroticNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (10)

- Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs: A Low Culture ManifestoNo EverandSex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs: A Low Culture ManifestoNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (1428)

![The Inimitable Jeeves [Classic Tales Edition]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/audiobook_square_badge/711420909/198x198/ba98be6b93/1712018618?v=1)