Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

The Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm For Clinicians II (HOAC II) : A Guide For Patient Management

Enviado por

Boopathi PTDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm For Clinicians II (HOAC II) : A Guide For Patient Management

Enviado por

Boopathi PTDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

䢇

Perspective

The Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm

for Clinicians II (HOAC II):

A Guide for Patient Management

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

In this era of health care accountability, a need exists for a new

decision-making and documentation guide in physical therapy. The

original Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians (HOAC) pro-

vided clinicians and students with a framework for science-based

clinical practice and focused on the remediation of functional deficits

and how changes in impairments related to these deficits. The HOAC

II was designed to address shortcomings in the original HOAC and be

more compatible with contemporary practice, including the Guide to

Physical Therapist Practice. Disablement terminology is used in the

HOAC II to guide clinicians and students when documenting patient

care and incorporating evidence into practice. The HOAC II, like the

HOAC, can be applied to a patient regardless of age or disorder and

allows for identification of problems by physical therapists when

patients are not able to communicate their problems. A feature of the

HOAC II that was lacking in the original algorithm is the concept of

prevention and how to justify and document interventions directed at

prevention. [Rothstein JM, Echternach JL, Riddle DL. The Hypothesis-

Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians II (HOAC II): a guide for patient

management. Phys Ther. 2003;83:455– 470.]

Key Words: Decision making; Diagnosis; Physical therapy profession, professional issues.

Jules M Rothstein, John L Echternach, Daniel L Riddle

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003 455

The HOAC II is a revised algorithm

designed to meet the needs of

I

n 1986, Rothstein and Echternach1 published a

clinical decision and documentation guide called contemporary practice.

the Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians

(HOAC), which they contended offered clinicians

addressing goals noted by someone other than the

a pragmatic, scientifically credible approach to patient

patient.

management. Since that algorithm was first published,

radical changes have occurred in the health care system.

The focus on patient-centered outcomes was, however,

For example, there is now widespread discussion of the

an innovation in HOAC and laid a foundation for the

importance of physical therapists making diagnoses,2

implementation of the HOAC in clinical decision mak-

and there is also general acceptance of the need to view

ing in the context of currently used disability models.

patients and clients within the context of one of the

The disablement model that we believe currently offers

disability models.3,4 In addition, therapists often have to

the greatest utility for clinical practice is the Nagi

relate to practice guides and guidelines.5 We argue that

model.7(pp223–241) A common element in both the old

what is needed is a patient management system that

and new versions of the HOAC is that therapists using

involves the patient in decision making and can be used

the terms of the Nagi model are called upon to identify

to provide payers with better justifications for interven-

impairments, when appropriate; to examine how these

tions, including occasions when therapists may disagree

impairments relate to functional deficits; and to exam-

with practice guidelines. Compatibility with the Guide to

ine whether interventions designed to ameliorate or

Physical Therapist Practice’s (Guide’s) patient manage-

reduce impairments result in changes in function and

ment model, including the formulation of diagnoses, is

changes in levels of disability. In some cases, therapists

also desirable.6

also can hypothesize that factors other than impairments

may lead to functional loss. For example, a societal

The purpose of this article is to present HOAC II, a

limitation such as high curbs may contribute to a

revised algorithm designed to meet the needs of con-

patient’s inability to walk to school. We also believe

temporary practice. The algorithm, we believe, is com-

therapists have a role in prevention7(pp84 – 89) and that in

patible with the American Physical Therapy Association’s

a responsibility-focused health care system clinicians

(APTA’s) Guide to Physical Therapist Practice,6 including

should identify the hypotheses that underlie interven-

the therapists’ need to diagnose and to offer interven-

tions used for prevention.

tions designed to prevent problems. In the context of

the HOAC II, a problem is almost always a functional

We believed that the original HOAC could serve both as

deficit. Although we attempted to be consistent with

a template for documentation and as a conceptual

Guide terms, there are instances where we used alternate

model for decision making and, therefore, could link

terms for the sake of clarity.

documentation and practice. This does not mean, how-

ever, that we believe either the original HOAC or the

Although the original HOAC was a first effort at bring-

HOAC II must be implemented in the exact form we

ing scientific decision making into a user-friendly prac-

have written it, for all patients, in all settings. Rather, we

tical context for clinical decision making, it has some

contend that elements can be selected based on practi-

cumbersome elements as well some logical and proce-

cality and the expected benefit of using a system in

dural flaws. The algorithm offered no guidance on how

which all elements of patient management are explicitly

to determine when an intervention designed primarily

detailed. The HOAC II, we contend, provides a means

for prevention was appropriate and how risk factors

for not only using evidence in decision making, but also

could be eliminated. The algorithm also did not ade-

for documenting the nature and extent of evidence

quately provide a means for identifying problems and

used. Within the new version, elements related to justi-

JM Rothstein, PT, PhD, FAPTA, is Professor, Department of Physical Therapy, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago,

1919 W Taylor St, 4th Fl, Room 456, Chicago, IL 60612 (jules-rothstein@attbi.com). Address all correspondence to Dr Rothstein.

JL Echternach, PT, EdD, ECS, FAPTA, is Professor and Eminent Scholar, School of Physical Therapy, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, Va.

DL Riddle, PT, PhD, is Professor, Department of Physical Therapy, Medical College of Virginia Campus, Virginia Commonwealth University,

Richmond, Va.

All authors provided concept/idea/project design, writing, and project management. The authors acknowledge the efforts of Andrew Guccione,

PT, PhD, FAPTA, Julie Fritz, PT, PhD, ATC, and David Scalzitti, PT, MS, OCS, for reviewing an earlier draft of the manuscript.

This article was submitted March 12, 2002, and was accepted December 2, 2002.

456 . Rothstein et al Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

fication of interventions (eg, where evidence can be arguments that are data (evidence) based. Hypotheses

cited) should be part of any credible system of that guide intervention to eliminate existing problems

documentation. (PIPs or NPIPs) can be tested because a change in

something can be measured (eg, changes in impairment

Overview of Elements in HOAC II levels and disability). Changes in what is measured will

In developing the revised algorithm, we recognized that be identified in the part of the algorithm where reassess-

there are usually 2 major types of patient problems: ment occurs.

(1) those that exist when the patient is being seen and

that require remediation and (2) those that may occur in A problem is kept from occurring when anticipated

the future and that require prevention. We also realized problems are correctly managed. Therefore, no observ-

that even though clinicians do not necessarily routinely able change usually relates directly to the problem. More

discuss these differences, clinical management of the 2 importantly, in the absence of anything observable or

types of problems is different, and assessment of the measurable, a justification based on an outcome is not

outcomes for each must differ. possible for interventions aimed at prevention, because

even without intervention a problem may not have

While there are 2 types of problems (existing and arisen.

anticipated), there are also 2 ways that problems are

identified. There are patient-identified problems (PIPs) Testing criteria are used to examine the correctness of

and non–patient-identified problems (NPIPs). Patient- hypotheses related to problems that currently exist. For

identified problems, which usually consist of functional NPIPs or PIPs that are anticipated, however, the thera-

limitations and disabilities, often exist when the thera- pist establishes predictive criteria, which, if met, indicate

pist sees the patient. The patient identifies the problem. that problems will most likely be avoided because risk

The therapist, however, needs to generate hypotheses as factors were reduced or eliminated. A predictive crite-

to the cause of problems and to establish testing criteria, rion for a patient with low back pain, for example, may

which can be used to evaluate the outcomes of interven- be that a patient is considered no longer at risk when the

tions, and the correctness of the hypothesis and patient patient can perform stretching exercises at a suitable

care strategies. The patient may identify existing prob- level of performance on a regular basis (the predictive

lems as well as express concerns relating to problems criteria would detail the specific exercise and how often

that do not yet exist and could, therefore, be the source it should be performed).

of an anticipated problem. For example, a patient may

complain of shoulder pain and express a concern about To justify any predictive criterion, the therapist should

the development of limitations in movements that could base the criterion on best available evidence. Patients

be disabling. The limitations in function caused by the with spinal cord injuries, for example, might no longer

pain would be an existing problem (eg, an inability to be considered at risk (ie, they have achieved the predic-

cook a meal because repetitive use of the shoulder tive criteria) for developing skin ulcers when they have

caused intolerable pain). Any loss of function that could shown that: (1) they will spontaneously do wheelchair

occur if motion became even more limited would be an pushups a given number of times per hour, and (2) they

anticipated problem. will monitor the status of their skin by having someone

check for red marks or abrasions at specified intervals. In

Non–patient-identified problems are problems that are each case, the predictive criteria relate to an observable

not identified by the patient. They are problems that behavior, not just increased awareness or knowledge.

may occur as well as existing problems. For example, The behavior ideally is justified based on identified

children may not be able to identify problems secondary evidence or sound theory and not just on assumptions.

to central nervous system deficits. A child might, for Circumstances may make it impossible to achieve goals

example, routinely sit in a position that compromises his with observed behaviors, and in these special circum-

or her ability to breath because of decreased thoracic stances knowledge may be a reasonable predictive crite-

excursion. The child is unlikely to see this as a problem, rion (eg, when the therapist cannot visit the patient’s

but a family member or a member of the health care workplace but teaches the patient strategies for avoiding

team could believe that a problem (NPIP) will develop. injury).

In this case, either the therapist or the caregiver will be

the most likely person to identify the problems. Simi- The dual problem lists, one for PIPs and one for NPIPs,

larly, patients who have had a stroke may have difficulty are merged into a single problem list as one proceeds

communicating about their problems, and others will through the algorithm. Throughout the rest of the

need to identify these problems. Justification for antici- algorithm, the source that identified the problem is not

pated problems, regardless of whether they are PIPs or a concern. What is critical, however, is that therapists

NPIPs, can, in the HOAC II, only be based on theory or manage anticipated and existing problems differently,

Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003 Rothstein et al . 457

and the algorithm provides parallel paths for the man- Using the Algorithm

agement of the 2 types of problems. This is particularly Part 1 of the algorithm deals with all 5 elements of the

important in the reassessment phase (Part 2 of the patient/client management model described in the

algorithm). The existence of a list of anticipated prob- APTA’s Guide to Physical Therapist Practice 6 (examination,

lems and the predictive criteria allows for the identifica- evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention). The

tion of which interventions are designed for prevention, Guide is not specific about issues related to the use of an

how these interventions are justified, and when interven- evaluative strategy to modify interventions and to test

tion can be stopped. A novel element of the HOAC II, hypotheses. In the Guide, however, under “Interven-

one that we believe has not previously been seen in tion,” it is stated: “Decisions about intervention are

physical therapy literature, are mechanisms to make contingent on the timely monitoring of patient/client

interventions designed for prevention goal oriented and response and the progress made toward achieving the

of determinate duration (ie, there is a stated goal that anticipated goals and expected outcomes.”6(p46) We

must be achieved and there is an expectation as to how believe, therefore, that Part 2 of our algorithm is an

long this will take). elaboration on one vital element of what the Guide

refers to as “intervention.” In the HOAC II, issues related

The algorithm provides clinicians with a mechanism for to monitoring intervention effects and altering the plan

planning and evaluating activities designed for preven- of care are covered in Part 2.

tion. This approach encourages therapists to work to

minimize risks through prevention, but, more impor- Part 1

tantly, it allows them to evaluate their efforts and to

describe and justify their efforts to one another, payers, Collect Initial Data (Includes the History)

managers, and others. Because in HOAC II prevention Early in an episode of care, clinicians start to obtain

activities are goal driven and are planned for specified information that they will use to guide all elements of

periods of time, therapists can, through use of the patient management. Practitioners appear to approach

algorithm, identify to payers the resources they will need each patient with a set of hypotheses and collect data to

to achieve prevention. This should, in our opinion, confirm or refute those hypotheses8,9; therefore, even

assure payers that interventions will not continue indef- initial data collection is hypothesis driven. During the

initely, unless that can be justified before the initiation interview, for example, questions about activities that

of the intervention. The algorithm also allows the ther- may have caused an injury are one sign that the clinician

apists to document when, in their professional opinions, is seeking to confirm or deny hypotheses. More experi-

prevention activities are needed and the consequences enced clinicians can be expected to generate hypotheses

of what will occur if these are not carried out (eg, due to earlier than less experienced practitioners9 and, in our

a lack of patient adherence or because they are not experience, more effective clinicians often feel a greater

authorized by payers). freedom to discard hypotheses and consider alternatives

as early as the interview phase of the patient

In a continued effort to keep focus on what are truly the examination.

patient’s goals, one problem list (the PIP list) is gener-

ated before the examination. In the HOAC II, there is a The algorithm does not specify the type and scope of

record, at least initially, of who identified the problem. A information gathered during the initial data collection

complete problem list, however, including problems phase. This remains the choice of clinicians, depending

identified by the therapist and others, and a complete set on their approach to practice. The algorithm simply

of goals are not generated until later in the process. requires clinicians to note what they do in this process.

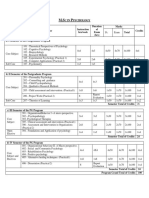

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate Part 1 of the HOAC II. Information that will be used to create a PIPs list needs

to be obtained during the initial data collection.

In Part 2 of the HOAC II, there are 2 reassessment paths,

one for existing problems and one for anticipated Patients seeking physical therapy have expectations of

problems (Figs. 3 and 4). In each case, there are what therapy should offer them, and these may differ

questions on a flow diagram that direct therapists from what their therapists feels are reasonable. A patient

through relatively simple steps that are taken in response may believe that walking without an assistive device

to questions. Two flow diagrams are used to describe the should be the goal, for example, whereas the therapist

reassessment, one for existing problems and one for may contend that this would be impossible and walking

anticipated problems. A list of commonly used terms with a device would be a reasonable goal. Among the

operationally defined for the HOAC II is provided in the essential data that clinicians must collect are clear non-

Appendix. medical descriptions of expectations, particularly

descriptions of those disabilities and functional limita-

tions that need to be eliminated. Incongruence among

458 . Rothstein et al Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

Figure 1.

The initial steps of Part 1 of the Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians II (HOAC II).

Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003 Rothstein et al . 459

Figure 2.

The final steps of Part 1 of the Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians II (HOAC II).

460 . Rothstein et al Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

Figure 3.

The algorithm for reassessment of existing problems in Part 2 of the Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians II (HOAC II).

Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003 Rothstein et al . 461

Figure 4.

The algorithm for reassessment of anticipated problems in Part 2 of the Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians II (HOAC II).

462 . Rothstein et al Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

expectations of the patient, a payer, a referral source, appear to be better able to identify sources of data

and a therapist will be considered when problem lists are needed for hypothesis testing.10 We believe many new

generated, but information about the differing expecta- therapists, like many new physicians, often conduct a

tions needs to be obtained early in the process. plethora of tests because: (1) they have been taught

methods of patient management that require suspension

Generate a PIPs List of hypothesis generation until all the data are collected,

Generating the PIPs list is one of the easiest things to do or (2) they do not have enough experience to generate

in the HOAC II. It requires clinicians simply to record a tentative idea (hypothesis) on which to base a focused

patients’ reports of the problems that led them to seek examination strategy. We recognize that, for some

physical therapy (or the medical care that led to a patients, therapists may be unable to generate examina-

referral for physical therapy). Therapists ask patients tion strategies, and the algorithm calls for consultation

about what they can and cannot do (ie, what limitations when this occurs and provides a mechanism for docu-

they have in function). A functional limitation or disabil- menting and justifying the use of a consultant.

ity is a problem, and, in some cases, patients also may

express concerns that they have a condition that could When using the HOAC II as a guide to documentation,

lead to the development of loss of function in the future. therapists must describe their examination strategies,

In this way, a patient could be the one who identifies an including how they arrived at these strategies (based on

anticipated problem. The therapist, however, with con- available data) and why they believe the chosen exami-

sultation with the patient, needs to determine whether nation techniques will lead to information that can be

the patient’s concern is realistic and, if the anticipated used to confirm or deny hypotheses. This may appear to

problem is justified, add it to the problem list. require a lot of information. Notes in the patient’s

medical record, however, may be as simple as “the

Because the HOAC II emphasizes accountability, we patient’s inability to walk down stairs may be due to

believe therapists should never assume that any patient balance problems. Testing of balance appears to be most

concern about the future means that an anticipated important, and tests of muscle force and range of

problem will occur. Only when the therapist can supply motion will be conducted to rule out less likely causes of

evidence or a sound theoretical argument to support the the functional limitation.” In this example, the balance

possibility of the anticipated problem occurring should testing directly addresses the hypothesis, whereas muscle

it be placed on the list, which is true regardless of the force measurements and range-of-motion measurements

source. Evidence is preferred over theory when the could lead to rejection of the hypothesis. The important

therapist believes that the patient’s concern about future element is that a link exists between the logic that guides

events is not warranted. The therapist needs to discuss the examination strategy, the information available, and

the reasons with the patient and, to enhance account- the therapists’ hypothesis. This does not require elabo-

ability, document that the discussion took place (ie, if rate documentation on the part of the therapist.

the patient’s concern was not added to the problem list,

explain why). Conduct the Examination and Analyze the Data

Examination procedures for a given type of patient may

Formulate Examination Strategy be governed by departmental policies, critical paths, or a

Based on the initial data collected and the nature of the variety of other influences. Ideally, approaches should

PIPs, the therapist needs to determine what other infor- be data driven (evidence based) and based on research

mation is needed. This is an examination strategy, and it suggesting best methods of examination and data anal-

cannot exist independently of hypotheses. When gener- ysis.11 The HOAC II does not specify how or what to

ating the examination strategy, the therapist is not yet examine, but, for the process to be useful, the examina-

able to identify a best hypothesis as to the cause of the tion must follow logically from the examination strategy

patients’ problems (both PIPS and NPIPS). The thera- and not include extraneous procedures if they are not

pist may have several competing hypotheses and needs part of the examination strategy. That is, examination

to develop an examination strategy that will obtain procedures should be related to the tentative hypothe-

information to confirm correct hypotheses and negate ses, either to confirm or to reject those hypotheses. The

nonviable hypotheses. Unless a therapist has some ten- measurements obtained during this phase should be of

tative ideas (hypotheses) as to what may be causing the the type and quality specified by the APTA’s Standards for

problems (eg, the potential impairments or pathologies Tests and Measurements in Physical Therapy Practice.12

causing functional limitations or disabilities), there can

be no examination strategy. For documentation, all descriptions and analysis of the

data obtained during the examination should be clear.

Experienced clinicians appear to generate hypotheses Reasons why hypotheses were supported or rejected

more readily than less expert clinicians, and they also need to be specified, and, when findings call for addi-

Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003 Rothstein et al . 463

tional examination procedures, this should also be Anticipated problems are usually risk factors, for future

described. pathologies, impairments, functional limitations, and

disabilities. The problem is the risk factor, and the

Add NPIPs to the Problem List intervention will be aimed at eliminating the risk fac-

Just as existing and anticipated problems are on the PIPs tors. Sometimes an exacerbated risk factor may be

list, existing and anticipated problems are on the NPIPs contributing to functional limitation or disability. In a

list. The anticipated problems require special consider- person with low back pain, for example, inappropriate

ation because they involve prevention, whereas the cur- lifting techniques may be the reason for an existing

rent problems are those, including functional limitations problem (ie, activities cause pain, which limits function),

and disabilities, that were not initially described by the but continued use of poor techniques following the

patient. NPIPS may be identified as early as the initial current episode could lead to recurrence. Poor lifting

data collection phase, but they do not formally appear in techniques may be a cause of an existing problem, and

the HOAC II until after the examination, when the this needs to be addressed when the therapist generates

NPIPs list is completed. hypotheses regarding the causes of existing problems.

The poor lifting techniques also could be the cause of an

Sometimes, particularly with children or those with anticipated problem because they put the patient at risk

communication disorders, caregivers or family members for future disability.

may describe current problems. In this case, the prob-

lems may be described in the initial data collection Justification for Hypotheses

phase. These problems are placed on the NPIPs list, but, The therapist makes 2 types of justification based on the

in the context of the HOAC II, will be managed in a nature of the problem (existing or anticipated) and

similar way to the other existing problems on the PIPs chooses one of 2 paths in the algorithm. Existing prob-

list. The problems are not different in nature, but only in lems require one type of argument, that is, hypotheses

the source of identification. The therapist, however, is about the diagnosis that detail what needs to be changed

responsible for the management of the problems on the to eliminate existing problems. Anticipated problems

NPIPs list regardless of the source that identified the require a different kind of justification for the elimina-

problem. tion of risk factors and a case as to what may happen

without intervention. Both types of justification should

Anticipated problems are different than existing prob- be evidence based to the extent possible.

lems, and, in the HOAC II, management of anticipated

problems is a central feature. Following a transtibial Generate a Hypothesis (or Hypotheses) as to Why the

amputation, for example, a person is likely to develop a Problems Exist

knee-flexion contracture.13 The therapist is likely to Each existing patient problem has an underlying cause

know this, and the patient is not likely to know this. The or causes. In the HOAC II, the cause is usually due to an

therapist also will know that if a contracture develops, impairment that is present, but in some cases the cause

the patient may be unable to use a prosthesis and may could also relate to pathology, functional limitations,

lose function. societal limitations, or disabilities. Interventions, we

believe, need to be focused on eliminating causes of

Identification of anticipated problems often requires problems. However, unless clinicians state, during clini-

therapists to consider anticipated impairments to pre- cal problem solving and documentation, why they

vent functional limitations and disability, but anticipated believe problems exist, it is often difficult to justify

problems may also be pathologies. A therapist, for interventions or to see how they relate to problems.

example, should be aware that returning a patient with a Students, for example, often find it difficult to see how

compromised cardiovascular system to full activity with- their clinical instructors determined what intervention

out the patient being able to monitor his or her own vital to use. Similarly, payers may not be able to discern why

signs could cause a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or a therapist focuses on an isolated motor skill instead of a

myocardial infarction. Here the anticipated problems functional task during intervention unless the therapist

are pathologies that could be prevented by teaching the hypothesizes that a relationship exists between the iso-

patient how to monitor his or her cardiovascular status. lated skill and functional activities. The hypotheses gen-

The patient also may be the source for anticipated erated during this step provide the link between the

problems, and, although these are in the PIPs list, they therapist’s diagnosis and the intervention. No interven-

are managed in a way that is similar, in the context of the tion for an existing problem should be conducted unless

HOAC II, to the way all other anticipated problems are it relates to the hypothesized cause of a problem.

managed.

Often the causes of disabilities will be the presence of

pathologies, impairments, and functional limitations.

464 . Rothstein et al Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

Many physical therapy interventions focus on impair- pists, and, more importantly, the intervention is not

ments and functional limitations, and therefore most designed to change the pathology, but rather the impair-

diagnostic hypotheses will be directed at the impairment ment and disability that the pathology caused. In addi-

and functional limitation dimensions. Sometimes, how- tion, the pathology (as measured with magnetic reso-

ever, therapists will attempt to eliminate a pathology. nance imaging, for example) would likely be

When this occurs, the pathology is the hypothesized unchanged, even though the intervention successfully

cause. When a therapist believes that a wound fails to dealt with the impairment or functional limitation.

close because of infection, for example, the hypothesis

could be at the level of a pathology; that is, unless the The critical elements of hypotheses are that they deal

sepsis is eliminated, the wound will not close. This would with elements that would be affected by the intervention

be a testable hypothesis because wound cultures could and that they must be sufficiently clear to allow for the

be requested. Hypotheses that identify suspected pathol- generation of testing criteria. The testing criteria that

ogies often cannot be tested by physical therapists therapists generate must represent pathology, impair-

because most therapists are unable to request invasive ments, or functional loss that can be measured in clinical

tests or radiological diagnostic tests. Therapists usually practice. As discussed earlier, when a previously undiag-

need to consult with and possibly refer patients to a nosed pathology is hypothesized to be present, consul-

physician to determine when a pathology is identified as tation with or referral to a physician may be required to

the diagnosis in a hypothesis.10 confirm the hypothesis. A problem may have more than

one underlying cause, and, in these cases, the therapist

The HOAC II, like the original algorithm, places an may generate multiple hypotheses. The therapist also

emphasis on hypothesis generation and requires the would generate testing criteria for each hypothesis. This

therapist not only to determine what may be causing the might occur, for example, when weakness and a lack of

problem (eg, loss of muscle force, loss of motion), but to coordination are hypothesized to be the reasons why a

also postulate as to the magnitude of the deficits (eg, how person can no longer ambulate independently.

much weakness a patient has and how much force would

be needed for the problem to be eliminated). The For Each Anticipated Problem, Identify the Rationale for

amount of force needed will serve as the testing criteria Believing Anticipated Problems Are Likely to Occur

for the hypothesis. Therefore, when generating hypoth- Unless Intervention Is Provided

eses, therapists must understand that in a subsequent Physical therapists, like many other health care profes-

step they must quantify what must be achieved to elimi- sionals, share beliefs about what is happening and what

nate the problem. One way of determining whether a may happen to their patients. Some of these beliefs are

hypothesis is appropriate is to consider whether such based on data that identify risk factors, factors that once

testing criteria could be generated. In the wound exam- eliminated should reduce the possibility of future nega-

ple, the criteria would be a report of a negative culture. tive health outcomes. The Framingham study, for exam-

This example demonstrates that even when the hypoth- ple, identified many risk factors for cardiovascular dis-

esis is at the level of pathology, generation of testing ease.14 Epidemiological studies of this type are usually

criteria must be possible. the means for justifying interventions designed to elim-

inate risk factors. Unfortunately, data often are lacking

Hypotheses that identify impairments as the cause of for beliefs that health care professionals have about risk

disabilities and functional losses are even easier to factors.

generate. If a person cannot walk following a CVA, for

example, it would be incorrect in the HOAC II to On what data do physical therapists act? The question is

hypothesize that the cause is damage to the motor a legitimate patient management and resource alloca-

cortex. Although this may be true, the quantification of tion query. Without evidence to support the value of

the type and extent of pathology is not observable and elimination of risk factors, the possibility of excessive

measurable by physical therapists. The diagnostic intervention exists. Too little intervention for risk factors

hypothesis may be that the person cannot walk because also is a possibility. The HOAC II provides a mechanism

he or she lacks the ability to generate sufficient quadri- for therapists to use either epidemiological data or

ceps femoris muscle force during stance. In this exam- theoretical constructs to justify interventions aimed at

ple, the problem is a functional deficit, and the hypoth- reducing risk factors. The former is data based or

esis relates the functional deficit to an impairment. The evidence based, whereas the latter uses argumentation

testing criteria will be the amount of force the therapist and logic that should have some scientific basis.

believes the patient needs to be able to generate to Evidence-based arguments are preferred.15

eliminate the problem (ie, to walk). Had the hypothesis

identified a pathology (damage to the motor cortex), By using the algorithm, justification is explicit rather

the pathology could not be measured by physical thera- than implicit and can be discussed by all relevant parties.

Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003 Rothstein et al . 465

We contend that unless physical therapists can provide short-term goal is teaching the patient an exercise to

either good presumptive arguments or data to support strengthen a paretic limb. Strengthening would relate to

interventions aimed at reducing or eliminating risk a long-term goal in which that limb might be used for

factors, the role of therapists in prevention will be ambulation. We believe this approach is confusing.

increasingly challenged and possibly eliminated. When Changes in the force-generating capacities of muscles

therapists provide evidence to support their decisions, may indeed help some patients to achieve functional

however, little reason exists to deny interventions if the activities, but the goal is the function—strengthening

risk-benefit ratio is reasonable. When therapists can only may or may not be a means to that end. We contend that

provide arguments, the case is less clear. if all a therapist achieves is increased force capacity, the

patient has gained little or nothing from therapy. To

When using the HOAC II, we believe therapists must consider a change solely in an impairment as meeting a

discuss all anticipated problems in the documentation goal, in our opinion, is almost always inappropriate.

and provide arguments and evidence as to why they

believe that a problem would occur without interven- In the HOAC II, impairment changes are monitored

tion. This applies to justification for all interventions through the testing criteria and usually are not goals. All

related to anticipated problems and diminishes the of the goals used in the HOAC II must represent

likelihood of unnecessary interventions or of interven- meaningful accomplishments.16 That is, meeting a goal

tions continuing after they are no longer necessary. We as written in the algorithm means the patient’s function

believe this documentation will not only enhance patient has changed meaningfully. Some functions may be

care but also will make our interventions more credible, recovered sooner than others, and these can be identi-

particularly those aimed at prevention. fied as short-term goals. The overriding issue is that long-

and short-term goals represent the same kind of phe-

Refine Problem List nomenon (meaningful change for the patient) and the

The problem list at this point in the algorithm contains only difference is the time needed to achieve them. The

2 types of problems (existing and anticipated) derived simplest way of checking whether a goal is really

from 2 sources (the patient and all other sources). The meaningful in the HOAC II context is to consider:

therapist needs to determine whether the problems can (1) whether anyone would feel therapy was worthwhile if

be addressed by physical therapy interventions. If the this is all that is achieved and (2) whether the payer

patient needs the intervention of another health care would find therapy to be worthwhile if this is all that is

practitioner, the therapist needs to make a referral and achieved.

document why the referral is necessary. If the therapist

believes that the problem cannot be addressed, such as Many patients, such as people with CVAs, may, in theory,

when no intervention would help, the therapist needs to have many problems, and they might have a rather long

discuss this with the patient and: (1) remove the prob- list of goals they want to achieve to perform activities of

lem from the list of problems to be addressed by physical daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living

therapy, (2) document why the problem could not be (IADL), and other activities. Goal lists for such patients

eliminated, and (3) document the discussion that took might seem almost infinite in scope and impractical in

place and describe what was agreed on with the patient. length. For patients such as these, the therapist needs to

The therapist may believe that some problems can only work with the patient to identify those goals that are

be modified and not be fully eliminated. Again, the most important and those that are indicative of various

therapist should make this modification in the problem levels of difficulty. A therapist may list as a goal “inde-

list, discuss it with the patient, and document the nature pendence in brushing teeth,” for example, and use this

of the discussion. to represent a variety of similar tasks requiring eye-hand

coordination, such as using utensils for eating. In this

For Each Problem, Establish One or More Goals way, not all goals have to be listed, but rather there

should be those that are especially important to the

Existing problems. In the HOAC II, like the original patient and those that represent a hierarchy and diver-

algorithm, there is one type of goal—something that the sity of motor skills that could serve as goals.

patient needs to achieve. Goals are almost exclusively

expressed in terms of functional activities that the Anticipated problems. Therapists and patients need to

patient wants or needs to perform. Often therapists and work together to eliminate existing problems to achieve

others have used the term “short-term goal” not only to goals that they have delineated together. The goal for an

indicate something that can be achieved in less time anticipated problem is to prevent the problem from

than long-term goals, but also to indicate changes in occurring.

levels of impairments they believe are related to long-

term goals. A therapist might say, for example, that a

466 . Rothstein et al Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

For Each Existing Problem, Establish Testing Criteria rationale for each anticipated problem (see section

In the HOAC, the word “hypothesis” is used because it titled “For Each Anticipated Problem, Identify the Ratio-

has a mechanism for therapists to test whether their nale for Believing Anticipated Problems Are Likely to

ideas about causes of problems (ie, their diagnoses) may Occur Unless Intervention Is Provided”).

be correct. Only controlled studies can provide data as to

whether interventions lead to desired effects. In clinical The testing criteria for existing problems are used to

practice, however, the issue is whether we can provide examine the viability of the hypothesis. The predictive

interventions that we believe are effective. We believe criteria for the anticipated problems are different from

one mechanism by which that can be done is the use of the testing criteria. A goal for an existing problem can be

a systematic approach to patient management. The achieved within a known time period. If we are trying to

HOAC II, we believe, allows such an approach for the keep something from happening, when do we declare

integration and use of the best evidence available. The we have succeeded? In health care, often the best we can

HOAC II requires hypothesis testing in clinical practice. do is to eliminate risk factors; therefore, the predictive

In the context of the HOAC II, the therapist has a criteria relate to risk factors. If risk factors can be

hypothesis as to what is causing a problem, and usually eliminated during some finite time period, the predic-

that is an impairment leading to diminished function. tive criteria would reflect this possibility.

An impairment is a loss of function in an organ or

system, such as a loss of motion, strength, or coordina- For example, if a patient is seen as being at risk for the

tion. These losses are all measurable. Therefore, if the postsurgical development of pneumonia (a pathology),

intervention is focusing on the cause of the problem, as pneumonia would be an anticipated problem. Physical

the impairments lessen, function should improve. The therapy interventions may be gait training and breathing

problems should be diminishing, and goals should be exercises. Both of these interventions are preventive

closer to attainment. At times, a problem may be hypoth- because they relate to the potential reduction in risk of

esized to be caused by multiple impairments. But how do pneumonia. The predictive criteria for ambulation may

we know whether we have identified the correct diagnos- be a certain distance walked per day, whereas the

tic hypothesis? predictive criteria for the breathing exercises may be an

inspiratory level with an inspirometer and an observed

In the HOAC II, changes in the impairment measure are level of competence in generating a productive cough.

almost always monitored. The level of improvement in When these predictive criteria are achieved, the patient

impairment that the patient needs to achieve to elimi- should no longer need the preventive interventions.

nate the problem is called the “testing criteria.” When

multiple impairments occur, each will have to be mea- This finite situation can be contrasted with people who

sured, with testing criteria established for each. When have permanent disabilities and chronic injuries who

testing criteria are met, the problem should have been may have to reduce risk factors for the rest of their lives.

eliminated and the related goals achieved. In this way, A patient with recurrent back pain, for example, may be

the therapist tests the original hypothesis for existing taught prophylactic exercises, and the predictive criteria

problems. may be a level of competence and degree of adherence

in doing those exercises. When the desired level of

For Each Anticipated Problem, Establish Predictive competence and adherence is achieved—that is, when

Criteria the predictive criteria have been achieved—the patient

The conceptual basis for the testing criteria comes from would no longer need ongoing physical therapy inter-

the application of traditional scientific methods of vention. The assumption is that the patient would con-

inquiry into clinical practice. Unfortunately, this cannot tinue to carry out the exercises as taught, or that the

easily be done for anticipated problems. In science, therapist might need to see the patient periodically to

proving a negative is often seen as impossible because determine whether the predictive criteria are still being

hypotheses are not testable in the usual sense. If we met (ie, the patient is still performing the exercises with

intervene to prevent a contracture, for example, we the appropriate frequency and in the proper manner).

cannot prove that we achieved anything. The failure of a

contracture to develop may be due to an intervention or The predictive criteria are used to determine how long

because a contracture would not have developed any- interventions designed for prevention should be carried

how. With an anticipated problem, however, we can out. In this way, predictive criteria are somewhat similar

argue that, based on what is known, something might to goals, but they exist only for anticipated problems.

have occurred had we not intervened. Therefore, the They are not goals because they are worth achieving only

means of justifying interventions focused on prevention if sufficient evidence indicates that a problem might

is not in this part of the algorithm, but rather it is occur. The value of achieving the predictive criteria is

described in the section where therapists supply the

Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003 Rothstein et al . 467

entirely dependent on the case made for anticipating intervention. Family members, other health care person-

that a problem might occur. nel (eg, physical therapist assistants), and other caregiv-

ers all may have a role in implementing tactics. The

Establish a Plan to Reassess Testing and physical therapist, however, should note who is imple-

Predictive Criteria and Establish a Plan to menting which tactics. We believe the therapist must

Assess Problems and Goals recognize that, as long as these tactics are part of the

Hypotheses often require multiple testing criteria, and physical therapy plan of care, the therapist must assume

changes in the impairments measured for these criteria responsibility for overseeing, evaluating, and determin-

may not all change at the same rate. Similarly, achieve- ing whether modifications should be made to tactics.

ment of various predictive criteria may not happen at the

same time. Measuring impairments and disabilities and Part 2

doing a re-evaluation at every session is time-consuming In Part 1 of the HOAC II, the therapist working with the

and impractical. Therapists should have reasonable patient and others developed an intervention plan (a

expectations as to when meaningful and therefore mea- series of strategies and tactics that is conceptually similar

surable changes will occur and should plan a to the plan of care as defined in the Guide).6 Justifica-

re-evaluation schedule accordingly. Similarly, not all tion for the interventions was based on the therapist’s

goals can be achieved at the same time, and therefore concepts of what was causing problems. Therefore, by

they should be checked based on a logical plan (ie, definition, much of what occurs in Part 1 arises from

short-term goals should be checked sooner than-long conceptual models that can only be examined in the

term goals). By committing to an evaluation schedule, a context of intervention (eg, did the intervention lead to

therapist using the HOAC II has identifiable points in a desired outcome?). Part 2 is far less conceptual in

time when the patient’s status will be reconsidered. nature and consists of questions that are designed to

Without such a plan, re-evaluation is often chaotic, and provide insights into whether any aspect of patient

measurements may be obtained at intervals that may management is deficient, including whether the original

make interpretation of data difficult. goals were viable.

Plan Intervention Strategy and Tactics The steps in Part 2 can be used for documentation, or

If the therapist thinks muscle weakness is the impair- they can be used to less formally guide decision making.

ment contributing to a disability, the most obvious The most important element, however, is that, by using

approach would be to use exercise to increase the Part 2, the therapist must account for all changes in

force-generating capacity of the involved muscles. The goals, tactics, strategies, and hypotheses. In addition, the

strategy would be the use of exercise. Describing the therapist needs to document whether the criterion mea-

strategy alone is insufficient, because many types of sure chosen is still viable and whether it is still reasonable

exercises exist. The HOAC II asks therapists to describe to expect to see the desired change in the criterion

the tactics (specific exercises and frequency) they would measure. Part 2 not only assists in the evaluation process,

use. If we were dealing with an anticipated problem it provides the logical framework for examining the

(such as the development of postoperative pneumonia), effects of all interventions. Use of Part 2 requires the

there might be 2 strategies: (1) teach the patient how to therapist to document what happened to a patient, even

clear his or her airway and (2) teach the patient preven- if the result is an acknowledgment that the result was less

tive measures such as frequent ambulation and use of an than was expected. Documentation may be particularly

inspirometer. The tactic for the first strategy (airway useful on occasions when factors outside of the thera-

clearance) may be to have the patient cough a specified pist’s control led to a termination of the intervention.

number of times per hour (and the patient could be For example, by following the steps in Part 2, a therapist

shown how to determine if the cough is productive). The can make an argument to a payer that goals were not

tactic for generalized prevention might be correct use of achieved (even though progression was being made on

an inspirometer 5 times daily and ambulation 5 times the criterion measure) because there was too little time

daily. Strategies are broad statements of what types of allowed for the intervention.

things need to be done, whereas tactics are the elements

of the intervention. Tactics specify the frequency, dura- Part 2 consists of 2 flow diagrams. The first diagram

tion, and intensity of the interventions. (Fig. 3) leads the therapist through a series of questions

for all existing problems (regardless of who generated

Implement Tactics them). The second diagram (Fig. 4) also consists of a

Once tactics have been identified, they need to be series of questions, but these questions relate to antici-

implemented. Most often the therapist will be doing the pated problems (regardless of who generated the prob-

implementation. Sometimes, as when a person has a lem list). The peculiar nature of prevention (ie, thera-

home exercise program, the patient may be doing the pists may take credit for what does not occur by making

468 . Rothstein et al Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003

ўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўўў

sure a risk factor is reduced or eliminated) leads to ability to place a limb on a target with less than a

somewhat different questions. The most notable differ- specified number of errors. If all 3 criteria were met and

ence is that the first question when dealing with antici- the patient achieved the goal of dressing himself or

pated problems is asking whether the problem has herself, the therapist could not be certain whether this

occurred. If it has, prevention did not work, and a new goal still could have been obtained if only 2 of the 3

problem needs to be added to the existing problem list. testing criteria were met. The therapist, however, may

develop an opinion based on the time course of events;

Examining the Hypothesis for Existing Problems that is, how did the attainment of the goal over time

If a patient’s goals are met (the problems are resolved), relate to changes in the testing criteria? This case

the question remains as to whether this occurred illustrates how, even in the absence of being able to

because of the intervention. Although causality cannot definitively test hypotheses, therapists can better under-

be claimed in the absence of controlled studies, the stand patient management by use of the algorithm. In

algorithm and use of the testing criteria allow therapists this manner, the HOAC II serves as a means of ongoing

to gain some insights as to whether their approaches feedback for professional development, independent of

seemed appropriate and their interventions beneficial and what occurs with each patient.

therefore whether their hypotheses were appropriate.

Summary

When therapists set the testing criteria, they are stating The HOAC II was designed to facilitate the use of

that a level of performance (usually of an impairment science and evidence in practice, and to do so in a

measure) is needed for the goal to be achieved. If the manner that is not intrusive on clinical practice. We

goal is achieved and the testing criteria are not met, the believe that much of what we ask clinicians to do in the

therapist’s hypothesis is incorrect (or the criteria’s levels algorithm is already part of their practice but that it

were incorrect). If the testing criteria are met and the occurs in a less defined manner and without a context

goal is not achieved, the hypothesis is at best incomplete; for documentation and discussions among colleagues.

that is, other causes may exist in addition to those Among the differences between this version and the

identified, or those identified are irrelevant. These are original HOAC are the mechanisms for justifying pre-

absolute examples. What is less clear is what is happen- vention and, more importantly, for developing measur-

ing when there is movement toward meeting goals and able outcomes related to prevention as well as defining

when there is also an indication that the impairments the time it will take to achieve reduction of risk factors.

measured for the testing criteria are also becoming less

pronounced. In these cases, no simple test of the viability References

of a hypothesis exists, so the therapist must extrapolate 1 Rothstein JM, Echternach JL. Hypothesis-oriented algorithm for

clinicians: a method for evaluation and treatment planning. Phys Ther.

and consider the overall picture and determine whether

1986;66:1388 –1394.

the hypotheses and criteria should be maintained in the

same form. 2 Delitto A, Snyder-Mackler L. The diagnostic process: examples in

orthopedic physical therapy. Phys Ther. 1995;75:203–211.

When a therapist thinks a problem has multiple causes 3 Jette AM. Introduction: physical disability. Phys Ther. 1994;74:379.

and generates multiple hypotheses, it is impossible to say 4 Jette AM. Physical disablement concepts for physical therapy

with certainty whether achieving appropriate levels of all research and practice. Phys Ther. 1994;74:380 –386.

the testing criteria led to attainment of a goal. The 5 Feder G, Eccles M, Grol R, et al. Clinical guidelines: using clinical

possibility exists, for example, that if there were 3 guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318:728 –730.

hypotheses, 2 of the hypotheses were correct and the 6 Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. 2nd ed. Phys Ther. 2001;81:

third hypothesis was either redundant or unnecessary. 9 –744.

When all testing criteria are achieved, the therapist has 7 Pope A, Tarlov A, eds. Disability in America: Toward a National Agenda

no way of knowing what would have happened with this for Prevention. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1991:84 – 89,

patient if only 2 hypotheses had been met. 223–241.

8 Elstein AS, Shulman LS, Sprafka SA. Medical Problem Solving: An

Following a CVA, a patient might be incapable of Analysis of Clinical Reasoning. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University

dressing. Among the many possible causes of this deficit Press; 1978.

could be: (1) weakness, (2) lack of coordination, and (3) 9 Payton OD. Clinical reasoning process in physical therapy. Phys Ther.

poor position sense. All 3 might be hypothesized as 1985;65:924 –928.

causes of the problem. Testing criteria for weakness 10 Goodman CC, Snyder TEK. Differential Diagnosis in Physical Therapy.

could be a force level obtainable on a hand dynamom- 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 2000.

eter. For the lack of coordination, the testing criteria 11 Sackett DL, Haynes RB, Guyatt GH, Tugwell P. Clinical Epidemiology:

might be a level of performance on a coordination test, A Basic Science for Clinical Medicine. 2nd ed. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown

and, for position sense, the testing criteria might be the and Co Inc; 1991.

Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003 Rothstein et al . 469

12 Task Force on Standards for Measurement in Physical Therapy. 14 Dawber TR. The Framingham Study: The Epidemiology of Atherosclerotic

Standards for tests and measurements in physical therapy practice. Phys Disease. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1980.

Ther. 1991;71:589 – 622.

15 Straus SE, Sackett DL. Getting research findings into practice: using

13 May BJ. Assessment and treatment of individuals following lower research findings in clinical practice. BMJ. 1998;317:339 –342.

extremity amputation. In: O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ, eds. Physical

16 Randall KE, McEwen IR. Writing patient-centered functional goals.

Rehabilitation: Assessment and Treatment. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: FA

Phys Ther. 2000;80:1197–1203.

Davis Co; 2000:632– 633.

Appendix.

Terms Used in the Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians II (HOAC II)

Anticipated Problems:

These can be identified by the patient, the physical therapist, or any Non–Patient Identified Problems (NPIPs):

other person and are statements that describe deficits that the therapist These are problems identified (at least initially) by people other than the

believes will occur if an intervention is not used for prevention. patient but that are added to the patient’s problem list after consultation

with the patient (these can be existing or anticipated problems).

Examination Strategy:

This is the plan for examination that a physical therapist uses based on Patient-Identified Problems (PIPs):

the therapist’s experience, available data relating to the patient, and These are problems identified by the patient (these can be existing or

information on similar patients. Because not all possible tests and anticipated problems), and because they are generated by the patient,

measures are used, the choice is considered a hypothesis-driven strat- they cannot be removed from the problem list without the patient’s

egy in the HOAC II. consent.

Existing Problems: Predictive Criteria:

These can be identified by the patient, the physical therapist, or any These are critical values (thresholds) for measurements, which, if met,

other person and are statements that describe deficits in a person’s would indicate that one or more problems will most likely be avoided

function (disability). because risk factors were reduced or eliminated. Sometimes the mea-

surement may be how often someone does a task or whether a patient

Goals: demonstrates competency in a prevention program (eg, does stretching

Functional deficits are problems, whereas goals are descriptions of or prophylactic back exercises).

function that will be recovered as a result of one or more interventions.

Tactics:

Hypothesis: These are the elements of an intervention. For instance, the exercises or

The reason that a patient’s problems (which are usually at the disability techniques used to treat the patient or client are the specific elements of

level) exist is not necessarily known, but in order for a physical therapist the intervention, whereas the overall purpose of the interventions is the

to carry out an intervention, the therapist must have an idea as to the strategy.

underlying causes. In the HOAC II, the therapist’s conjecture as to the

cause is a hypothesis. Often there will be more than one hypothesis, and Testing Criteria:

usually the hypothesis will involve one or more impairments causing a These represent critical values (thresholds) for measurements, which, if

deficit in function (ie, a disability). achieved, would suggest the hypothesis (or hypotheses) is correct if the

associated problem(s) is resolved (these are most often measurements of

Intervention Strategy: impairments).

These are the overall types of interventions that the physical therapist

believes are needed to alleviate problems (eg, exercises designed to

increase range of motion are a strategy, whereas the specific exercises

are tactics).

470 . Rothstein et al Physical Therapy . Volume 83 . Number 5 . May 2003

Você também pode gostar

- Kirk D. Strosahl, Patricia J. Robinson, Thomas Gustavsson Brief Interventions For Radical Change Principles and Practice of Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy PDFDocumento297 páginasKirk D. Strosahl, Patricia J. Robinson, Thomas Gustavsson Brief Interventions For Radical Change Principles and Practice of Focused Acceptance and Commitment Therapy PDFebiznes100% (18)

- DSM-IV Criteria MnemonicsDocumento4 páginasDSM-IV Criteria Mnemonicsleonyap100% (1)

- Code of EthicsDocumento10 páginasCode of Ethicsgee wooAinda não há avaliações

- Energy Medicine For Men: The Ultimate Power Tool For Guys Who Want Their Lives To WorkDocumento10 páginasEnergy Medicine For Men: The Ultimate Power Tool For Guys Who Want Their Lives To WorkJed Diamond88% (8)

- Miller 2010Documento9 páginasMiller 2010FarhanAinda não há avaliações

- Hypnosis With ChildrenDocumento3 páginasHypnosis With Childrengmeades0% (1)

- Family Therapy (FT) - Experiential Family TherapyDocumento13 páginasFamily Therapy (FT) - Experiential Family Therapyandreshion100% (2)

- Chapter 1 - Foundations of Psychiatric - Mental Health NursingDocumento5 páginasChapter 1 - Foundations of Psychiatric - Mental Health NursingCatia Fernandes100% (2)

- On Being Sane in Insane Places PDFDocumento8 páginasOn Being Sane in Insane Places PDFEdirfAinda não há avaliações

- Safe Patient HandlingDocumento2 páginasSafe Patient Handlingapi-3697326Ainda não há avaliações

- Existential TherapyDocumento31 páginasExistential Therapybianca martin100% (6)

- Cellulite Current Treatments, New Technology, And.3Documento7 páginasCellulite Current Treatments, New Technology, And.3BoeroAinda não há avaliações

- Part B: Manual Extract: Patient-Centered Informed Consent in Surgical PracticeDocumento10 páginasPart B: Manual Extract: Patient-Centered Informed Consent in Surgical PracticeNaveen Abraham100% (2)

- Crisis Intervention PaperDocumento15 páginasCrisis Intervention Paper00076640167% (3)

- The Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm For Clinicians II (HOAC II) : A Guide For Patient ManagementDocumento16 páginasThe Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm For Clinicians II (HOAC II) : A Guide For Patient Managementangelica barrazaAinda não há avaliações

- Ptj1681 An Integrated Framework For Decision Making in Neurologic Physical Therapist PracticeDocumento22 páginasPtj1681 An Integrated Framework For Decision Making in Neurologic Physical Therapist PracticeEileen Torres CerdaAinda não há avaliações

- Lang 2020Documento8 páginasLang 2020Asmaa GamalAinda não há avaliações

- Strategiesfor Ethical Practicein Medical SettingsDocumento14 páginasStrategiesfor Ethical Practicein Medical SettingsGBAinda não há avaliações

- Provider of Care 3 Clinical Teaching Plan - FINALDocumento12 páginasProvider of Care 3 Clinical Teaching Plan - FINALmaha abdallahAinda não há avaliações

- Public HealthDocumento60 páginasPublic HealthJeyma DacumosAinda não há avaliações

- Case Study 3 Clinical Governance in Primary CareDocumento4 páginasCase Study 3 Clinical Governance in Primary CareEmadeldin ArafaAinda não há avaliações

- Hypothesis Oriented AlgorithmDocumento7 páginasHypothesis Oriented AlgorithmROSHAN RAJANAinda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento3 páginasUntitledLoiseAinda não há avaliações

- And Differential: Red Flag Screening Diagnosis in Patients With Spinal PainDocumento11 páginasAnd Differential: Red Flag Screening Diagnosis in Patients With Spinal PainDaniel LopesAinda não há avaliações

- Utility of Work Based Assessment Among Surgical Residents: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocumento8 páginasUtility of Work Based Assessment Among Surgical Residents: A Systematic Literature ReviewUsama AzizAinda não há avaliações

- PhysiotherapyDocumento7 páginasPhysiotherapySimer ChawlaAinda não há avaliações

- 2 Making Clinical Decicions - Lifespan Neurorehabilitation 2018Documento28 páginas2 Making Clinical Decicions - Lifespan Neurorehabilitation 2018Abi Dennise Nahuelpán LienlafAinda não há avaliações

- Ethics, Privacy, and Security (Week 16)Documento5 páginasEthics, Privacy, and Security (Week 16)JENISEY CANTOSAinda não há avaliações

- Mobile Phones For Health Workers in Primary CareDocumento3 páginasMobile Phones For Health Workers in Primary CarePranay DasAinda não há avaliações

- Information: Design and Execution of Integrated Clinical Pathway: A Simplified Meta-Model and Associated MethodologyDocumento23 páginasInformation: Design and Execution of Integrated Clinical Pathway: A Simplified Meta-Model and Associated MethodologyGrupo de PesquisaAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Cliical Focus For Online RleDocumento2 páginasSample Cliical Focus For Online RleFitz JaminitAinda não há avaliações

- Use of The ICF Model As A Clinical Problem-Solving Tool in Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation MedicineDocumento10 páginasUse of The ICF Model As A Clinical Problem-Solving Tool in Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation MedicineThiago LacerdaAinda não há avaliações

- Council For International Organizations of Medical Sciences (Cioms)Documento64 páginasCouncil For International Organizations of Medical Sciences (Cioms)potato xAinda não há avaliações

- How To Apply ICF in Rehabilitation PDFDocumento14 páginasHow To Apply ICF in Rehabilitation PDFCyndi MenesesAinda não há avaliações

- ADocumento7 páginasARaphael AguiarAinda não há avaliações

- Wadsworth 1983 Wrist and Hand Examination and InterpretationDocumento13 páginasWadsworth 1983 Wrist and Hand Examination and Interpretationdorsijowi87Ainda não há avaliações

- RCP 421: Clinical Internship in Respiratory Care: Learning ContractDocumento4 páginasRCP 421: Clinical Internship in Respiratory Care: Learning Contractapi-401501805Ainda não há avaliações

- RPS Form SEMANA 2 PDFDocumento10 páginasRPS Form SEMANA 2 PDFJavier CarrascoAinda não há avaliações

- Ignment of Program Outcomes, Field of Study Outcomes, Course Outcomes, Course Learning OutcomesDocumento5 páginasIgnment of Program Outcomes, Field of Study Outcomes, Course Outcomes, Course Learning OutcomesKit LaraAinda não há avaliações

- Information Systems: Quantitative MethodsDocumento2 páginasInformation Systems: Quantitative MethodsAnagha M NairAinda não há avaliações

- A Conceptual Framework For Performance Assessment in Primary Health CareDocumento8 páginasA Conceptual Framework For Performance Assessment in Primary Health CareA FEBRYAN RAMADHANIAinda não há avaliações

- Claudia Baez-Camargo Eelco Jacobs: Working Paper SeriesDocumento22 páginasClaudia Baez-Camargo Eelco Jacobs: Working Paper SeriesanisAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Evaluation Reports 6 Years After Meddev 27 - 1 Revision 4Documento4 páginasClinical Evaluation Reports 6 Years After Meddev 27 - 1 Revision 4יוסי קונסטנטיניסAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture.1 LeadershipDocumento6 páginasLecture.1 LeadershipJulian Felipe Peña RamirezAinda não há avaliações

- Mhealth-Innovations SystemstrengtheningtoolsDocumento12 páginasMhealth-Innovations SystemstrengtheningtoolshmounguiAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Solving ToolDocumento10 páginasClinical Solving ToolJeg1Ainda não há avaliações

- Capstone Poster Wei Wu FinalDocumento1 páginaCapstone Poster Wei Wu Finalapi-398506399Ainda não há avaliações

- Williams Et Al 2023 Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Systemic CancerDocumento7 páginasWilliams Et Al 2023 Practical Assessment and Management of Vulnerabilities in Older Patients Receiving Systemic CancerAniket KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Learning Objectives Asynchronous Learning Topic Tasks / Activities Synchronous Learning Topic Tasks / Activities AssessmentDocumento2 páginasLearning Objectives Asynchronous Learning Topic Tasks / Activities Synchronous Learning Topic Tasks / Activities AssessmentZheefAinda não há avaliações

- Ipc CC MisDocumento1 páginaIpc CC MisLorena HernandezAinda não há avaliações

- Maab Khalil Poster Capstone FinalDocumento1 páginaMaab Khalil Poster Capstone Finalapi-408489180Ainda não há avaliações

- 499 FullDocumento6 páginas499 FullJosh DelgadoAinda não há avaliações

- Public-HealthDocumento60 páginasPublic-HealthMomoh NyaleyAinda não há avaliações

- Publication Asset 0027Documento53 páginasPublication Asset 0027Ahmad DobeaAinda não há avaliações

- What Comes After Traditional Psychotherapy ResearchDocumento6 páginasWhat Comes After Traditional Psychotherapy ResearchAlejandra GuerreroAinda não há avaliações

- Task Overlap Among Primary Care Team Members An OpDocumento13 páginasTask Overlap Among Primary Care Team Members An OpDwi SulissAinda não há avaliações

- 2022 BMJ Open - Models of Care For Low Back PainDocumento7 páginas2022 BMJ Open - Models of Care For Low Back PainMiguel Arévalo-CárdenasAinda não há avaliações

- Health Recommendation System: Datta Meghe College of EngineeringDocumento16 páginasHealth Recommendation System: Datta Meghe College of EngineeringESHAAN SONAVANEAinda não há avaliações

- Operational Research Applied To Decisions in Home Health CareDocumento33 páginasOperational Research Applied To Decisions in Home Health Careroyiv72493Ainda não há avaliações

- DOH Clinical Privileging of HCWDocumento21 páginasDOH Clinical Privileging of HCWahamedsahibAinda não há avaliações

- Low Back Pain: It Is Time To Embrace Complexity: Julia M. HushDocumento4 páginasLow Back Pain: It Is Time To Embrace Complexity: Julia M. HushRilind ShalaAinda não há avaliações

- Telehealth Technology Applications in Speech-Language PathologyDocumento7 páginasTelehealth Technology Applications in Speech-Language PathologyJose Alonso Aguilar ValeraAinda não há avaliações

- NARRATIVE Patterson WorkaroundstoHIT Humanfactors2018Documento12 páginasNARRATIVE Patterson WorkaroundstoHIT Humanfactors2018imam mahmud yeniAinda não há avaliações

- Ethics in Laboratory MedicineDocumento8 páginasEthics in Laboratory Medicineandika setionoAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical FocusDocumento6 páginasClinical FocusSheryll Almira HilarioAinda não há avaliações

- Patient Centric Pharmaceutical Drug Product Design-The Impact On Medication AdherenceDocumento23 páginasPatient Centric Pharmaceutical Drug Product Design-The Impact On Medication AdherenceShishir GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- Pbe ArtigoDocumento8 páginasPbe ArtigoKaline DantasAinda não há avaliações

- Health TechDocumento6 páginasHealth TechFebe ALONTAGAAinda não há avaliações

- Healthcare 4.0: Next Generation Processes with the Latest TechnologiesNo EverandHealthcare 4.0: Next Generation Processes with the Latest TechnologiesAinda não há avaliações

- Depression Among TeenagersDocumento4 páginasDepression Among Teenagersaufa sanuraAinda não há avaliações

- Psychological Disorder Case Study Project RubricDocumento3 páginasPsychological Disorder Case Study Project Rubricapi-509663069Ainda não há avaliações

- Motivation and AspirationDocumento4 páginasMotivation and AspirationSharmistha Talukder KhastagirAinda não há avaliações

- Rahul Shaik Kamala Kumari.P Syed Ahmed Basha: BackgroundDocumento6 páginasRahul Shaik Kamala Kumari.P Syed Ahmed Basha: BackgroundMutiarahmiAinda não há avaliações

- Temper TantrumsDocumento17 páginasTemper TantrumsgmfletchAinda não há avaliações

- Everly FlynnDocumento8 páginasEverly Flynnmohitnet1327Ainda não há avaliações

- Books Sensory Integration PDFDocumento4 páginasBooks Sensory Integration PDFBugiuianu GabiAinda não há avaliações

- Psychology1 PDFDocumento31 páginasPsychology1 PDFSiv RamAinda não há avaliações

- Grennan 2007Documento19 páginasGrennan 2007Căileanu CasianAinda não há avaliações

- CPLOL, ProfesiuneaDocumento4 páginasCPLOL, ProfesiuneananuflorinaAinda não há avaliações

- Eustress FinallyDocumento13 páginasEustress FinallysiyanvAinda não há avaliações

- Mental Health, Psychosocial Support Services and Psychological First AidDocumento102 páginasMental Health, Psychosocial Support Services and Psychological First AidDonna Flor Nabua50% (2)

- NSTP 1MT N Brochure Gañalon, JennahDocumento1 páginaNSTP 1MT N Brochure Gañalon, JennahJhasmine GañalonAinda não há avaliações

- Andreasen 1989Documento4 páginasAndreasen 1989RaquelAinda não há avaliações