Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Why I Didn't Vote

Enviado por

JoeyKuhn100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

666 visualizações6 páginasLz granderson: I didn't vote in the midterms, but I made a deliberate, reasoned choice not to vote. Granderson: my decision was motivated, quite simply, by my own ignorance. He says a recent Doritos bag reminded him of something fishy about the attitude toward elections. Lz: it's a shame that so many young people don't know how to vote properly.

Descrição original:

Título original

Why I Didn’t Vote

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

DOC, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoLz granderson: I didn't vote in the midterms, but I made a deliberate, reasoned choice not to vote. Granderson: my decision was motivated, quite simply, by my own ignorance. He says a recent Doritos bag reminded him of something fishy about the attitude toward elections. Lz: it's a shame that so many young people don't know how to vote properly.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOC, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

100%(1)100% acharam este documento útil (1 voto)

666 visualizações6 páginasWhy I Didn't Vote

Enviado por

JoeyKuhnLz granderson: I didn't vote in the midterms, but I made a deliberate, reasoned choice not to vote. Granderson: my decision was motivated, quite simply, by my own ignorance. He says a recent Doritos bag reminded him of something fishy about the attitude toward elections. Lz: it's a shame that so many young people don't know how to vote properly.

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato DOC, PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 6

Why I Didn’t Vote

This past November, my grandmother kindly went to the trouble of obtaining an

absentee ballot for me to vote in the Pennsylvania midterm elections, but I never filled

that ballot out, and it now lies in a trash heap somewhere. I wasn’t trying to spite my

grandmother. I made a deliberate, reasoned choice not to vote—yes, you can do such a

thing. I am not referring to a decision to abstain because neither major party strikes your

fancy, or because you reject the country’s entire political-economic system. My decision

was not guided by any such political angst, although such a motive for abstention may be

perfectly legitimate. No, my decision was motivated, quite simply, by my own ignorance.

But let me explain further.

As I approached the first election for which I would be of legal voting age, I was a

little puzzled as to why all my elder relations were so supremely concerned with whether

I planned to vote. Strangely, they did not seem at all concerned whether I would cast an

informed, judicious vote. None of them made any efforts to ensure that my political

education was sufficient, aside from tossing a few pro-life pamphlets at me. Of course,

this aroused my suspicion that my elders were only desirous to add one more tally to the

party of their own political persuasion.

My puzzlement at this odd approach to civic duty did not abate. It stuck with me

until I was recently reminded of it by, of all things, a Doritos bag. On the back of this bag

was a marketing shtick claiming, “Doritos Supports Kids Who Do Something!” (or along

those lines). The bag profiled a young man who had founded an organization to increase

the number of young people voting. Now, I must make it clear that I am fully in support

of the intentions of this noble endeavor. But this crinkly bag of snack food called my

attention back to something fishy about the prevailing attitude toward elections. This was

the same fishiness I had smelt around my relatives, and it consisted in this: the Doritos

bag praised this young man’s organization simply for increasing the youth vote by

250,000, or some number, without any mention of the quality of those votes.

It might seems strange to talk about the quality of a vote, but I believe it only

seems strange because we are not used to talking about it, and that is because all people’s

opinions must be regarded as equal, etc., etc. But when I say quality of a vote, I mean

simply the common notion, taught in all civics classes, that a citizen must investigate the

candidates thoroughly and make a sensible and impartial decision, to the best of his or her

abilities. Shouldn’t we be more concerned with the lack of voter quality than of voter

quantity? How does an increase in votes by 250,000 benefit the nation, if each of those

votes might have been chosen based on the names of the candidates or completely at

random, for all we know? Yet one seldom hears a big to-do made over any attempts by

individuals or organizations to enable the citizenry to carry out their civic duty with

prudence and justice. I am sure that such attempts exist—maybe the organization featured

on the Doritos bag even has an educational and informational branch—but this crucial

side of the duty of voting is too often ignored.

That Doritos bag represented to me what seems to be the common opinion of

voting in America (I am not sure about the rest of the democratic world). Around election

time, you hear one rallying cry taken up on all sides around you in the form of trite

slogans: “Get Out and Vote!” “Make Your Voice Heard!” These slogans have begun to

irritate me to no end, not because of what they advocate—of course everyone in a

democracy should participate in the government—but because they are never balanced by

the necessary and complementary exhortations: “Know Your Candidates!” “Research the

Issues!” “Be Fair-Minded and Consider the Common Good, Rather than Only Your Petty

Passions!” The common slogans imply that the duty of voting is fulfilled in a single

event, that voting is just something you go out and do on election day. But in reality, the

democratic duty to vote is a continual duty, and it involves much more than most people

would like to believe. It requires consistent attention to happenings in the public world,

whether on the national, state, or local level, and thoroughgoing investigation of the

candidates in the period running up to the election. It also requires a serious attempt to

grasp all the complexities and nuances involved in highly controversial issues. In short,

the duty of voting demands both time and mental effort, yes, even a lot of each. But such

is the sacrifice we must make to live in a free society. To the extent that each of us fails

to make these sacrifices, we let ourselves be guided by forces above our heads, and we

cease to be free.

While we’re on the topic, I might as well point out that those forces over our

heads are often the very forces that give us the illusion of freedom of choice. I am

referring to the media, to the advertising campaigns of the politicians, and to the

government itself. These agencies do very little to facilitate informed decisions, and often

actively stymie rational deliberation. In general, it is fairly safe to say that any media

message is strategically designed to work on your passions and prejudices, for one side or

the other. And of course, there are only two sides to every issue. Every political matter,

down to the tiniest administrative detail, is immediately turned into a game of tug-of-war

by ultra-polarized politicians and pundits, so that one can never even get the facts

straight. And the PR teams of most politicians do their utmost to make their candidate’s

platform as vague as possible and to keep any bits of concrete information from creeping

into campaign advertisements and websites. The portraits of the candidates that we get

from them are, of course, meticulously crafted.

Where can one turn in this quagmire? It would be nice if one could find an agency

or publication with the express purpose of providing busy citizens with clearly organized,

objective information on political candidates and governmental proceedings, but to my

knowledge no such agency exists. Entrepreneurial types, take note—here is an enormous

gap in the information market, just crying to be filled. And it seems that the Internet was

made for such uses. But to hope for a truly objective political news source is probably to

search for the philosopher’s stone. In the present state of things, there are some sources

of honest information and voices of intelligent opinion within the media, but these are

few and hard to find. They mostly hide out in the written species of media—newspapers,

magazines, and books, on paper or online. Unfortunately, fewer and fewer people pay

attention to these sources as they are drowned out by more insistent and illiberal voices

on the television and the radio.

Because of all the obstacles mentioned above, the best (maybe only) possible way

to be really informed about what you are voting for is to actually get involved in the

government and get know the candidates personally. Of course, that is pretty hard to do

on the national and even the state level, so your best bet is to start locally. Coincidentally,

the level of government that should affect your day-to-day life most directly (the local) is

also the level in which your voice can most easily have an actual impact. But

paradoxically, people seem to pay more attention to political matters the less power they

have to affect them. You may know everything there is to know about Barack Obama and

Sarah Palin, but can you even name your city council member or the mayor of your

town? I know I can’t.

Perhaps you might argue that the decisions of the federal government affect your

life much more than those of your municipal government. That may very well be the

case, but then we are faced with a different question: Is this how it ought to be? At any

rate, we know with certainty that it has not always been this way. Alexis de Tocqueville

observed that the strength and vivacity of the American democracy in the 19th century

depended on its highly local nature, centered around mostly autonomous townships. It

seems worrisome to me if the nation has gotten to the point at which the matters most

directly touching your home and your personal life are decided largely by people sitting

in a room thousands of miles away who have never been to your town and who cannot

possibly know its character and its needs. You “elect” these people, but you are forced to

do so based on projected facades and unreliable hearsay, for you have never had the

chance to meet them.

Now, back to why I didn’t vote. I make no claim to be the perfect citizen—far

from it. As I said, I don’t even know the names of any of my local representatives.

Laziness and neglect were part of the reasons why I didn’t vote in the midterms. If voting

is a duty, then I admit outright that I failed in that duty. But rightly recognizing the

problem is half of the solution. I failed because I failed to inform myself sufficiently

about the issues and the candidates over a period of time, not because I failed to check

some boxes on a piece of paper in some single instance of time. The reasons for this

failure were partially beyond my control, as I am a busy college student with little free

time to dedicate to following political news, and as the information needed to make an

informed and wise decision is not made easily available by either the media or the

candidates themselves. But my failure was also partially my own fault, as I could have

made more of an effort to learn about the political goings-on affecting the general public

rather than being so selfishly absorbed in my own college life.

The single-minded focus on increasing the quantity of votes is not an isolated

problem; it reflects a widespread, willful blindness to our nation’s most serious political

ills. Psychologically, it’s an easy phenomenon to explain. Our natural inclination as

humans is to avoid exertion whenever possible, and this applies no less to mental than to

physical exertion. That’s why we’re always trying to simplify issues that cannot really be

simplified, convincing ourselves that big problems are easy to solve. We want to believe

that if we just pitch in more money here or fire those people there, everything will come

up roses. This is the same reason why political discourse is so polarized now; it’s much

easier to fall back on a prepackaged platform than to actually have to do your own

thinking and research. That way you know who are the good guys and who are the bad

guys; everything is simple. What is this but sheer mental laziness?

So I admit that I failed in my democratic duty because I didn’t sacrifice enough

time and effort to bring myself to the level at which I felt sufficiently informed to vote;

but how much more do they fail in their duty who do not even recognize that they must

sacrifice much time and effort to bring themselves to this level? Was my failure any

worse than that of those who did vote, but voted for candidates they had never even heard

of based on mere party prejudice, or voted for candidates based on judgments they had

formed hastily from a few vague impressions gotten from TV or YouTube? Let us call

things what they are. If shortcoming is shortcoming, and failure is failure, than the vast

majority of those who vote also come short of the mark for a responsible citizen of a

democracy and fail in their democratic duty.

I realize that I am setting the mark extremely high, but a dose of idealism may be

just what the illness calls for. Someone in a democracy has to stand up for virtue and

excellence over mediocrity. I also realize that if my reasoning were put into practice,

almost nobody would allow themselves to vote. Or worse yet, the best and wisest men

and women, who are able to contemplate their own ignorance, would not vote, leaving

the vote entirely to the most foolish segments of the population. When I discussed my

argument in this essay with a friend, he replied, “But Joey, you’re probably more

knowledgeable about the candidates than a lot of the people who do vote!” I do not

dispute this point. This is why I am not recommending my decision as a pragmatic course

of widespread action. No person can presume to decide for any other person at what point

he or she is knowledgeable enough to cast a responsible vote. Where would you draw the

line? It would have to be arbitrary, just as the voting age is arbitrary. Thus, the decision to

vote or not to vote must be a matter of conscience. I did not vote because, like Socrates, I

was conscious of my own ignorance in the field of politics. My conscience told me that it

would be irresponsible and pointless for me to vote given my level of ignorance. All I can

ask you to do is to carefully consider, before you go to the ballot box, how much time and

thought you have put into your decision, and whether you are carrying out your duty to

your country in the manner of a truly responsible, educated, and upstanding citizen. If the

answer is less than satisfactory, you can still vote if you want to, but you must by all

means make an effort to get closer to that ideal by the next election. And all do-gooders

with well-formed intentions and less well-formed reasoning faculties can stop pestering

everyone to vote. If people aren’t voting, there’s probably a good reason for it, and we’re

probably better off because of it.

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Transports of The Foregone ManDocumento2 páginasTransports of The Foregone ManJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Sea ChangeDocumento4 páginasSea ChangeJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- War For My Soul - 3Documento2 páginasWar For My Soul - 3JoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Entertainment, Art, EnlightenmentDocumento6 páginasEntertainment, Art, EnlightenmentJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Portrait of T S EliotDocumento2 páginasPortrait of T S EliotJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Sliced N' DicedDocumento2 páginasSliced N' DicedJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Euclid PoemDocumento1 páginaEuclid PoemJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- The Missing Man of MysteryDocumento7 páginasThe Missing Man of MysteryJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- PreservationDocumento19 páginasPreservationJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Under The Feet of GiantsDocumento5 páginasUnder The Feet of GiantsJoeyKuhn100% (2)

- The Pittsburgh ZooDocumento3 páginasThe Pittsburgh ZooJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Our MotherDocumento8 páginasOur MotherJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Portrait of A Drunken BoyDocumento1 páginaPortrait of A Drunken BoyJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Minutes Crawl, Years FlyDocumento10 páginasMinutes Crawl, Years FlyJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Mysterious Ways: Ahhhhh Pain Pain Help Eating Me Pain Gnawing Biting Pain Make It Stop AhhhhhhDocumento6 páginasMysterious Ways: Ahhhhh Pain Pain Help Eating Me Pain Gnawing Biting Pain Make It Stop AhhhhhhJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Lessons Learned From PokémonDocumento5 páginasLessons Learned From PokémonJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Notre Dame de La GardeDocumento4 páginasNotre Dame de La GardeJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- InterrupDocumento2 páginasInterrupJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Exorcism From A DreamDocumento5 páginasExorcism From A DreamJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is A Little Too CrunchyDocumento5 páginasThe World Is A Little Too CrunchyJoeyKuhn100% (4)

- PrudenceDocumento1 páginaPrudenceJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- The Grapes of EnnuiDocumento10 páginasThe Grapes of EnnuiJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- NotesDocumento1 páginaNotesJoeyKuhnAinda não há avaliações

- Election Law Case Compendium San Beda School of Law A.Y. 2020 - 2021Documento10 páginasElection Law Case Compendium San Beda School of Law A.Y. 2020 - 2021Anne DerramasAinda não há avaliações

- Constitution and Bylaws Saddleback Valley Educators AssociationDocumento16 páginasConstitution and Bylaws Saddleback Valley Educators AssociationDhmoon1Ainda não há avaliações

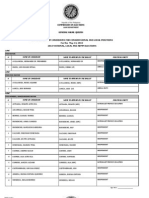

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento4 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Provincial Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- City of San Fernando, La UnionDocumento2 páginasCity of San Fernando, La UnionSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Shantanu MajumderDocumento18 páginasShantanu MajumderSyed Mohammad Hasib AhsanAinda não há avaliações

- Solving The Paradox: Rationality and Society November 2006Documento25 páginasSolving The Paradox: Rationality and Society November 2006Taruna BajajAinda não há avaliações

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Nolasco Vs ComelecDocumento4 páginasNolasco Vs ComelecKim Orven M. SolonAinda não há avaliações

- 5 Persuasive SpeechDocumento2 páginas5 Persuasive SpeechMark GatlabayanAinda não há avaliações

- Social Studies Exams Questions Js3Documento6 páginasSocial Studies Exams Questions Js3dutdeonAinda não há avaliações

- Ded Order 77 S 2009Documento5 páginasDed Order 77 S 2009Mia Luisa EnconadoAinda não há avaliações

- Counting and Appreciation of Ballots 100Documento109 páginasCounting and Appreciation of Ballots 100DM DGAinda não há avaliações

- Presidential Debates The Challenge of Creating An Informed Electorate by Kathleen Hall Jamieson, David S. Birdsell PDFDocumento273 páginasPresidential Debates The Challenge of Creating An Informed Electorate by Kathleen Hall Jamieson, David S. Birdsell PDFEly PAinda não há avaliações

- Arun Singh Rawat: Best 300Documento3 páginasArun Singh Rawat: Best 300Shubham VishwakaramaAinda não há avaliações

- Laua-An, AntiqueDocumento2 páginasLaua-An, AntiqueSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- General Nakar, QuezonDocumento2 páginasGeneral Nakar, QuezonSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Capstone Part-1 VivaDocumento11 páginasCapstone Part-1 VivaJyoti Arvind PathakAinda não há avaliações

- Projects of Precincts Banaybanay Davao OrientalDocumento6 páginasProjects of Precincts Banaybanay Davao Orientalinfoman2010Ainda não há avaliações

- N Advocates Act 1961 Ankita218074 Nujsedu 20221008 230429 1 107Documento107 páginasN Advocates Act 1961 Ankita218074 Nujsedu 20221008 230429 1 107ANKITA BISWASAinda não há avaliações

- A Win JooooeeeeDocumento6 páginasA Win JooooeeeeYagnesh KAinda não há avaliações

- Pulido Exam Suggested AnswersDocumento4 páginasPulido Exam Suggested AnswersGundamBearnardAinda não há avaliações

- Emeterio Cui V. Arellano UniversityDocumento7 páginasEmeterio Cui V. Arellano UniversityBernadette Luces BeldadAinda não há avaliações

- Research Proposal: Digitalization and Governance in PakistanDocumento8 páginasResearch Proposal: Digitalization and Governance in Pakistanrao umar saeedAinda não há avaliações

- LSHBDocumento47 páginasLSHBamit32527Ainda não há avaliações

- The Ethiopian Electoral and Political Parties Proclamation PDFDocumento65 páginasThe Ethiopian Electoral and Political Parties Proclamation PDFAlebel BelayAinda não há avaliações

- Company LawDocumento27 páginasCompany LawUpasana RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDocumento2 páginasCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- Manjuyod, Negros OrientalDocumento2 páginasManjuyod, Negros OrientalSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações

- The Problem and Its Scope Rationale of The StudyDocumento43 páginasThe Problem and Its Scope Rationale of The Studyfonz cabrillosAinda não há avaliações

- Cuyo, PalawanDocumento2 páginasCuyo, PalawanSunStar Philippine NewsAinda não há avaliações