Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Degustarea Vinului - Manual Senzorial

Enviado por

vinuriDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Degustarea Vinului - Manual Senzorial

Enviado por

vinuriDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Sensory User's Manual

Wine tasting can be an occasional pleasant diversion or a time-and-resource-consuming passion. It can be conducted casually or formally. No matter what level of orientation or dedication is involved, some basic background knowledge and a logical approach can greatly increase individual enjoyment. Most American wine drinkers cheat themselves by not knowing how to taste; many talk the talk but fail to walk the walk, so a lot of ordinary-tasting wines gets sold at extraordinary prices. Wine tasting is actually a complex proposition involving much more than simply sipping some fermented grape juice. There are many variable factors that affect an individual's perception of flavor in wine. There are chemical, physical, mechanical, physiological, and psychological variables. The type and quality of the wine itself is only one aspect of tasting. Others are the size and shape of the wine glass... the individual's impartial physiological ability to smell and taste, as well as his individual flavor preferences... the temperature of not only the beverage itself, but also the ambient temperature and humidity of the tasting site... how hungry, tired, and attentive the taster is can also affect relative judgment, as well as any preconceived notions and other psychological factors.

The Four Elements of Flavor

To understand these variables, let's first look at the phenomenon of taste from a physiological standpoint. Flavor, although it may have slightly differing meanings, depending upon who is using the term, always refers to food. A food chemist may use "flavor" only to refer to aroma, while a chef is likely to include taste, texture, temperature, appearance, and arrangement in his context. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines flavor as: FLAVOR: "Complex combination of the olfactory, gustatory and trigeminal sensations perceived during tasting. The flavour may be influenced by tactile, thermal, painful and/or kinaesthesic effects." While the senses of smell and taste are truly most important, flavor is not an experience limited to these, but a combination of experiences from the senses of smell, taste, touch, and, less obviously, sight.

ELEMENT ONE - SMELL: Acute, Ancient and Fragile

The nose can sometimes even beat the eyes in the race for setting up the tasting expectations. An aroma can carry from one room to another, beyond the line of sight. Of the five senses, smell is the most acute, approximately 1,000 times more sensitive than the sense of taste. As a result, what is termed flavor is influenced by roughly 75% smell (olfaction) and

25% taste (gustation) in healthy individuals. Ever notice how foods seem to taste bland or less distinctive when the nose is blocked by a cold? Smell and taste are the chemical senses because their receptors are stimulated by chemical molecules, rather than by energy from light, pressure, or sound. As little as one molecule in a million may be detected by the nose, but it takes a minimum of one part per thousand to stimulate the tongue. As sensitive and accurate as this organ is, relatively few people ever realize its potential for sensory enjoyment by learning how it works and the language of smells. Professional food and wine tasters and perfumers use analogies to common experience to describe aromas. Experts are those that practice and use their sense of smell most frequently. For a substance to be smelled, it must have a certain degree of volatility (be readily evaporating) and it molecules must be hydrophobic (able to dissolve in oil, but not water). Odor molecules are typically larger than those that stimulate taste.

Olfactory Membranes

The odor vapor must contact receptors which cover the organs of smell, a pair of olfactory membranes. Located deep in each uppermost nasal cavity, they are brownishyellow, roughly the size of a postage stamp, about two centimeters thick and covered in a thin layer of mucous, which the molecules must penetrate. There are 200 distinct kinds of nasal receptors. They function using 50 million olfactory neurons, each with cilia that extend into and through the mucous. On the cilia are the receptors that capture the scent molecules, signaling the neurons to send the scent message to the brain for interpretation. The sense of smell is ancient and primal, one of the earliest senses evolved, for locating food, warning of danger, and regulating sexual behavior. Unique among the senses, the scent message passes directly through the limbic system, the emotional center of the brain, on its way to conscious identification in the cortex. Reaction to certain smells may be instinctive; identification of those smells requires a certain amount of experience and training.

Fatigue and Adaptation

While smell is the most easily stimulated of the human senses, it is also the most fragile. Most of us have experienced detecting the aroma of cooking, maybe even from outside the house. In pursuit, we trace it to the kitchen where it becomes stronger. After standing there for a few minutes, however, the cooking odors may no longer be noticeable. This fatigue of the sense of smell is part of sensory adaptation: the self-adjustment to a constant level of stimulus in an environment, so that the individual retains sensitivity to changes. This adaptation also occurs for the sense of sight in a darkened theater or hearing in a noisy city. ..."fatigue of the sense of smell is part of sensory adaptation: the self-adjustment to a constant level of stimulus in an environment, so that the individual retains sensitivity to changes." Some adaptation is short-term; recovery and return to the degree of sensitivity prior to exposure may only take a few minutes. Research has also demonstrated that constant environmental odor exposure can cause adaptation that lasts for days or weeks, even after removal of the odor source.

There is a great variation between individuals in the elements to which they are sensitive. A person's absolute threshold is the smallest amount of stimulus required to produce a sensation. Once that threshold is reached, unless trained, the individual can only recognize and unconsciously catalog the smell as either "familiar" or "new". Scientists have proven that the nose can detect and distinguish between thousands of different smells, depending upon individual aptitude and training. Even individuals lacking the ability to smell specific odors (1anosmia) can often be induced to learn them by repeated exposure. Very little research has been conducted to either explain or rectify serious sensory problems of smell or taste, which can arise from congenital defect, illness, or injury, and may effect one of every 150 human beings2.

Aroma Theory

To date, scientists have cataloged over 17,000 different smells. About 10,000 can be distinguished by humans, although no one knows just how this ability works. In the early 1900s, a researcher named Henning suggested there are really only six categories of smells, combinations of which account for all the detectable odors and aromas. Henning arrayed these categories into a three-dimensional prismatic map whereon, his theory suggests, all smells could be plotted to some point on one of the surfaces. For example, it should be possible for something to smell fruity, putrid, resinous, and burned, but impossible to have a smell that is putrid, spicy, and resinous. The combinations are interesting to plot and contemplate. The chemical make-up of wine includes many trace elements that contribute to the combination of smells. Some of these same elements are also found, frequently in higher concentrations, in other familiar foods, spices, flowers, etc. Consequently, wine smells may often bring to mind these other familiar things, albeit with more subtlety and much less obvious or instant recognizability. With training, concentration, and practice, nearly anyone can learn to dissect and describe these elements of complexity.

ELEMENT TWO - TASTE: Categorization and Individual Sensitivity

While there may be a vast array of aroma categories, generally only four tastes have historically been considered: bitter, salty, sour, and sweet. There really is no precise definition of "basic taste"; these four only differentiate and describe common taste sensations. Bitter tastes come from alkaloids, such as contained in coffee and quinine (tonic water). Salty tastes, by far the most common in prepared foods, come from sodium chloride (table salt), sodium nitrite (especially in smoked meats or fish), sodium bicarbonate (especially in baked goods, canned foods), and sodium benzoate (especially in soft drinks and packaged beverages, jellies and preserves, margarine and fast-food burgers). Sour tastes come from acids (citric in oranges, grapefruit, etc., malic in apples, pears, lactic in dairy products). Sweet comes from sugars, primarily sucrose in the American diet, although there are many others (fructose, glucose, lactose, etc.). Tastes are sensed by nerve receptors called buds and there are about 9,000 of them on the average tongue. Combinations of tastes, along with the accompanying combined aromas, account for different flavors. Taste compounds have smaller molecules than those of odors and, unlike odors, must be hydrophyllic, water-soluble.

Sensitivity to specific tastes varies considerably with individuals. It is possible in fact to be tasteblind. The test uses a chemical called phenylthiocarbamide, which tastes extremely bitter to some persons and quite bland to others. Some research has suggested that there is higher alcoholism incidence among the genetically taste-blind.

Eastern Influence- The Concept of "Umami"

Additional theories of taste perception come into Western consciousness from Eastern thought. Asians generally add "hot" (the capiscum or capsaicin taste of peppers) to the four basic tastes. At the beginning of the 1900s, Japanese scientist Kikunae Ikeda identified this element as more complex and variable than merely hot. He isolated one element that causes this taste in meat, milk, mushrooms, and seaweed broth as the amino acid glutamate and called the sensation "umami." Rather than a specific flavor, umami is best described as a distinctive quality or completeness of flavor. The nearest English equivalent would be "savory" or "delicious." Oriental food often gets umami, its "complete" flavor, by the addition of monosodium glutamate (MSG). The scientific journal Nature published an article in the Spring of 2002, that American scientists Charles Zuker and Nick Ryber have identified a taste receptor for amino acids, supporting the idea of Umami. Wine typically contains from one to four grams of amino acids per liter. While still controversial, there are ongoing studies of umami and it is an emerging consideration in food and wine circles. More About Umami: Kalin Cellars' umami page has further thoughts and links concerning this element of taste.

The Taste "Map' of the Tongue is Bogus....

Taste has historically been one of the least understood sensory mechanisms. Misinterpretations of research conducted in the late 1800s, led to "tongue maps" that suggested that the basic tastes are sensed primarily by specific areas, such as the tip or center. Subsequent investigation proved that taste buds on the entire surface of the tongue can sense all of the various tastes.

ELEMENT THREE- FEELING: Texture, Body, Tannin, Alcohol and Temperature

The sense of touch figures in the overall flavor impression by conveying temperature, texture and pressure, the feeling differences that exist between cold iced tea and hot coffee, between plain fruit punch and carbonated soda, between filtered and unfiltered apple juice, between smooth pudding and crunchy cookies, or between the burn of jalapeo or the cool of menthol. These sensations of touch, irritation, or thermal differences are called chemesthesis and may be experienced in the eyes, mouth, nose, or throat. Much of the touch information of flavor is conveyed to the brain through the trigeminal nerve. The body of a wine is felt as light or heavy, thin or full, rich or crisp. Body is one of the most often misunderstood components of wine. The description "full bodied" is

frequently applied to wines that are high in either alcohol or tannin or in both, without the actual texture and weight of the wine being "full" at all. Body should be thought of as the relative "thickness" or viscosity of the wine. One of the most prominent elements of wine "flavor" is tannin, more a sensation of touch rather than taste. It is also a significant flavor component of tea, chocolate, soy, pecans, walnuts, and the skins and seeds of many fruits, other than grapes, such as blueberries, dates, kiwi, peaches, persimmons, pomegranates, raspberries and figs. Tannin leaves a puckery, astringent feeling on the tongue, gums, and cheeks and can sometimes also taste bitter. Wine tannins come primarily from grape skins and oak barrels and vary in strength and character. In the mouth, tannins can feel fine, round, and smooth or gritty, coarse, and angular. Tannins are one of the few flavor elements in wine that cannot be smelled. Alcohol also is mainly experienced as an irritation of the touch sense. When the proportion is too high for the other flavor elements, alcohol may give a "burning" sensation in the nose as well as a "hot" feeling in the back of the throat or the roof of the mouth. Wine served cold gives a taste impression that is less sweet and more acid and astringent than the same wine at a warmer temperature. This is one reason to serve fruity wines chilled, while dry, astringent ones are best near or just below "room" temperature. The phenomenons of fatigue and adaption discussed earlier regarding smell are also considerations with taste. Astringency and bitterness require up to ninety seconds recovery in order not to influence the flavor of the next wine. This can be a very long time between tastes. A good swallow of water or bite of bread helps. Sugar also takes a while to fade from the tongue. Chocolate, which combines astringency, bitterness and sweetness, has an extremely long aftertaste, can foul the palate for wine evaluation, and is not recommended within three hours prior to serious tasting. Cheese also clouds the ability to judge wine; as wise old French wine merchants say, "Achetez avec l'eau, vendez avec le fromage" (Buy with water, sell with cheese.)

Individual Preference and Cultural Bias

Another influence on taste besides individual physiology and ability is individual psychology and preference. Culture and upbringing provide sensory experiences that certainly influence adult taste preferences. Americans raised in the last half of the 20th Century typically drank milk, or increasingly soft drinks, sweet and sometimes carbonated, as mealtime beverages. The longtime adage of wine marketers has been that "Americans talk dry but drink sweet". Each culture has a similar taste bias. Coca-Cola employs 200 global research and development staff, two dozen of them specialists in flavor development to pinpoint local taste preferences and adjust their product formula to local conformity. They have found that Germans like spicy, Mexicans like citric and Italians want a little bitterness. These cultural flavor preferences may also dictate wine choices to some degree. Body should be thought of as the relative "thickness" or viscosity of the wine. Tannin: more a sensation of touch rather than taste. Tannin leaves a puckery, astringent feeling on the tongue, gums, and cheeks and can sometimes also taste bitter.

ELEMENT FOUR - SEEING: Clues Only; Don't be Fooled

This idea of sight affecting flavor is not hard to grasp if one thinks of some food which looks unappetizing, but then tastes very good. The reverse is also true. How often is an item selected from a cafeteria line that appears very tasty but turns out to be bland or worse? This expectation based on appearance often psychologically sets up our taste buds. In wine, this sight prejudice leads us to expect that transparent and bright wines will be good-tasting, and wines that are cloudy or dull in color will not. Although this does not necessarily hold, still our sense of sight sets us up psychologically for gustatory enjoyment or disappointment. Color can be an indicator of what the nose and the mouth might expect. Clues as to the grape varietal identity and the age of wine can be revealed by its hue and transparency or opacity. White varietal wines may appear from very pale greenish and brightly clear (suspect youth and bone dryness) to deep golden brownish and approaching translucence (probably well-aged, possibly nectar-like). Red varietals run from brickish red and nearly transparent (may be older, mellow) to deep opaque bluish-purple (expect young, brash, tannic). Bright pink ros or blush wines are often youthful, while orangey-bricky ones are usually past their point of prime drinkability. Although they may appear to be in a range of either red-purples or green-yellows, wine grapes are referred to as black (noir ) or white (blanc ), depending on the color of their skins at ripeness. Pinot Noir, Grenache and Mourvedre tend towards a garnet or brickish tone. Syrah, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc and Barbera can make wines so inky-purple they could refill fountain pens. The hues of the black grapes are consistent but they become nearly transparent when made into ros or blush-style wines. Sauvignon Blanc and Chenin Blanc tend to be green. Semillon and Viognier are generally more yellow. Gewurztraminer and Pinot Gris (Grigio ) can have a light tannish-grey cast if allowed to fully ripen before made into wine. Most unnamed varietals fall in between these color ranges. Sight may set up initial expectations in the other senses, or serve as confirmation after smelling, tasting, and feeling a wine's properties. When aromas of tomatoes, bouquet of earth, light tannins, a texture of velvet, and flavor of dried cherries all lead to suspicions of Pinot Noir, the garnet edge may confirm it.

METHODOLOGY: Putting it all together

Evaluating the physiological factors and chemical properties helps devise methodology to get the most from tasting wine. The taster can control serving parameters to intensify the experience and consider and maintain an awareness of elements which are beyond control but nonetheless affect the tasting occasion. First, to make sure enough vapor is present to get a strong sense of the wine's smell, use a glass shape that can concentrate the molecules, filled only one-third full or less to allow space for the vapors to be contained.

Tilting the glass over an opaque white surface and observing the liquid's edge is the best way to judge hue and clarity. Next, swirl the wine to toss some of those molecules into the air and to increase the size of the liquid surface area from which the molecules can escape. Then take a big, deep sniff of the wine to reach the deep-seated nasal receptors and cross the threshold of sensitivity. That first impression of a wine is really important. Close the eyes and concentrate to form an initial judgment before fatigue and adaptation set in. Taste- Put enough wine, one-half to a full ounce, in the mouth and slosh it around to make sure as large an area of the tongue as possible has a chance to judge the wine's elements. Feel the viscosity and tannins. Allow the wine to settle in the lower jaw, letting it warm slightly while pursing the lips to breathe in a small amount of air. Continue sucking in air, making a slurping sound as the wine and air mix. This volatilizes the wine and sends it to the back of the nasal cavity, intensifying the smell and flavor experience. After swallowing, notice which flavors and feelings are left and how well they linger.

Tasting Several Wines at One Sitting

Tasting several wines on the same occasion can somewhat alter the tasting procedure. Different contexts call for different techniques. When faced, for example, in a "blind" tasting, there are a couple of possible approaches. Whichever is comfortable and works best for the taster is proper. Wise old French wine merchants say, "Achetez avec l'eau, vendez avec le fromage" (Buy with water, sell with cheese.) One method is to sample and evaluate each wine completely and separately, before moving to the next one. For some people, this gives them a complete and memorable picture of the individual wine. A large "cocktail party" tasting event, where one glass, carried from table to table, is used to sample many wines, dictates this manner of tasting. A different technique may be used at "sit-down" wine tastings with "flights" of two or more wines. In this situation, it's possible to smell and evaluate all of the wines, before tasting any of them. Proceed through once, smelling each in order, then return to those that left the weakest impression for a second chance to coax more from them. Classify the wines, based on aromas, from "weak" to "strong" to "defective" to set the order of tasting. It requires discipline to delay tasting the strongest or most appealing wine, but it provides a chance to form a more definite impression of the lightest-smelling wines, without being overwhelmed by the "bigger" wines. Wines that have suspected defects, such as hydrogen sulfide (rotten egg), or TCA (corkiness), are postponed until last, to avoid "polluting" the senses. White varietal wines may appear from very pale greenish and brightly clear (suspect youth and bone dryness) to deep golden brownish and approaching translucence (probably well-aged, possibly nectar-like). Red varietals run from brickish red and nearly transparent (may be older, mellow) to deep opaque bluish-purple (expect young, brash, tannic).

TERMINOLOGY for Communication and Memory

Describing specific smells and flavors of wine is not important to the average consumer; most decide that a wine simply tastes good or not. Critics and judges, however, need to learn and apply standards of terminology. Consumers can enhance their tasting experience by learning these terms in order to communicate better with their fellow tasters, their wine merchant, and, perhaps most importantly, to develop a memory of their likes and dislikes. Many of the smells and flavors in wine are described in terms of other fruits. Gas chromatography enables separation and identification of elements in a compound, according to the constituent's volatility. This technique has enabled chemists to establish that there are, in fact, several odoriferous molecules that are shared by wine and apples, pears, currants, raspberries, oranges, or bananas. These include acetic and butyric acids, the alcohols propanol, terpinol and hexanol, the carbonyls ethanal, acetone and diacetyl, and the esters isoamyle acetate, ethyl caproate, and ethyl butyrate. Different combinations and amounts of these and other compounds give fruits their distinct aromas and flavors and provide great variety in wine. Until her retirement in 2003, from the University of California at Davis, Dr. Ann Noble led wine research on smells and flavors. She began to develop her theories on aromas specifically recognizable in wine in the 1980s and her colleagues continue this research today. Dr. Noble headed a project to develop an inexpensive and easy tool to aid in learning wine flavor terminology. The Aroma Wheel is a kind of pie-chart that lists, categorizes and groups hundreds of smells and odors that may be present specifically in wines. Each of these specific aromas is grouped into one of nine major general categories: floral, fruity, vegetative, nutty, woody, caramelized, earthy, spicy, or chemical. Dr. Noble's Aroma Wheel website explains how to get one and use it train your "nose and brain to connect and quickly link terms with odors...using materials available from the grocery store."

SUMMARY: Cheers!

A wine palate is part ability and part experience. The individual's preferences for and sensitivity to smell and taste elements, along with the memory of their taste history, combine to form the palate. In developing this personal wine palate, remember to consider the temperature, the texture, and the feel, as well as the flavors. Besides judging the wine, learn to recognize which flavor elements help you arrive at that judgment and use accepted terms to describe them. Use the swirl, sniff, and slurp method to enhance your tasting ability. When you find yourself absent-mindedly swirling, sniffing, and slurping your milk glass, coffee cup, or soda can, you have reached the first level of expertise and commitment to appreciating fine wine.

Read more: http://avalonwine.com/Tasting-Wine.php#ixzz15hP1p7ID

Você também pode gostar

- Brenda Patton Guided Reflection QuestionsDocumento3 páginasBrenda Patton Guided Reflection QuestionsCameron JanzenAinda não há avaliações

- Taste and SmellDocumento36 páginasTaste and SmellKarthikeyan Balakrishnan100% (2)

- The Sense of TasteDocumento6 páginasThe Sense of TastesuperultimateamazingAinda não há avaliações

- Explaining Zambian Poverty: A History of Economic Policy Since IndependenceDocumento37 páginasExplaining Zambian Poverty: A History of Economic Policy Since IndependenceChola Mukanga100% (3)

- Course For Loco Inspector Initial (Diesel)Documento239 páginasCourse For Loco Inspector Initial (Diesel)Hanuma Reddy93% (14)

- LH514 - OkokDocumento6 páginasLH514 - OkokVictor Yañez Sepulveda100% (1)

- 11 Paper Title Food Analysis and Quality Control Module-08 SensoryDocumento11 páginas11 Paper Title Food Analysis and Quality Control Module-08 Sensorymonera carinoAinda não há avaliações

- The Science of Taste, Smell and Flavor - LinkedInDocumento10 páginasThe Science of Taste, Smell and Flavor - LinkedInJessa Beth GarcianoAinda não há avaliações

- The Senses - Taste, Smell, TouchDocumento23 páginasThe Senses - Taste, Smell, TouchAlvand HormoziAinda não há avaliações

- How Does Our Sense of Taste Work - National Library of Medicine - PubMed HealthDocumento3 páginasHow Does Our Sense of Taste Work - National Library of Medicine - PubMed HealthBill LeeAinda não há avaliações

- Taste Disorders: NIDCD Fact Sheet - Taste and SmellDocumento4 páginasTaste Disorders: NIDCD Fact Sheet - Taste and SmellSerli JuliyantiAinda não há avaliações

- The Technology of Flavours PDFDocumento6 páginasThe Technology of Flavours PDFPancho Sagrera AlmuzaraAinda não há avaliações

- Dila MateriDocumento4 páginasDila MateriAnisa Farah DillaAinda não há avaliações

- The Nose Knows: Discover The Difference Between Taste and SmellDocumento6 páginasThe Nose Knows: Discover The Difference Between Taste and SmellAntoniio Ernestto CoronaAinda não há avaliações

- IELTS Placement Test Reading PassageDocumento2 páginasIELTS Placement Test Reading PassageKayabwe GuyAinda não há avaliações

- Special SensesDocumento6 páginasSpecial SensesGunal KuttyAinda não há avaliações

- Taste and SmellDocumento39 páginasTaste and SmellAyi Abdul BasithAinda não há avaliações

- The Technology of Flavours PDFDocumento14 páginasThe Technology of Flavours PDFtimheatwoleAinda não há avaliações

- Sensory MarketingDocumento11 páginasSensory MarketingCarina PerticoneAinda não há avaliações

- Gustatory and Olfactory Senses: of Sensory Physiology. New YorkDocumento11 páginasGustatory and Olfactory Senses: of Sensory Physiology. New Yorktherisa adarethAinda não há avaliações

- Smell & TasteDocumento4 páginasSmell & Tasteminji_DAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4 TastingDocumento11 páginasChapter 4 TastingHannah Mae BolalinAinda não há avaliações

- Running Head: CHEMICAL SENSES 1Documento7 páginasRunning Head: CHEMICAL SENSES 1Carter CarsonAinda não há avaliações

- What Are Taste BudsDocumento3 páginasWhat Are Taste BudsLoumelyn Rose B. BayatoAinda não há avaliações

- Taste and Taste Work in LanguageDocumento26 páginasTaste and Taste Work in LanguageSallarAinda não há avaliações

- The Flavour of Pleasure: Passage 1Documento4 páginasThe Flavour of Pleasure: Passage 1monkeyAinda não há avaliações

- Molecular Gastronomy Used in BakeryDocumento64 páginasMolecular Gastronomy Used in BakeryIyer Guhan67% (3)

- The Complicated Equation of SmellDocumento3 páginasThe Complicated Equation of SmellpatgabrielAinda não há avaliações

- LidahDocumento2 páginasLidahNur AsiahAinda não há avaliações

- Awareness of TasteDocumento3 páginasAwareness of TasteAndreaKószóAinda não há avaliações

- Sense of TasteDocumento10 páginasSense of TasteGatita LindaAinda não há avaliações

- Người siêu vị giác và vị giác yếu: Bình thường có tốt hơn không- wed HarvardDocumento15 páginasNgười siêu vị giác và vị giác yếu: Bình thường có tốt hơn không- wed HarvardNam NguyenHoangAinda não há avaliações

- Universiti Kuala Lumpur Malaysian Institute of Chemical & Bioengineering TechnologyDocumento6 páginasUniversiti Kuala Lumpur Malaysian Institute of Chemical & Bioengineering TechnologyNur AsiahAinda não há avaliações

- Organoleptic Properties of FoodDocumento2 páginasOrganoleptic Properties of FoodVeronica ZayasAinda não há avaliações

- Taste SystemDocumento24 páginasTaste SystemDipanshi shahAinda não há avaliações

- Physiology o F GustationDocumento26 páginasPhysiology o F GustationPrakash PanthiAinda não há avaliações

- Sensory - Unit 1Documento45 páginasSensory - Unit 1AKASH SAinda não há avaliações

- Sense of TasteDocumento13 páginasSense of TastefihaAinda não há avaliações

- Aroma WheelDocumento7 páginasAroma WheelQuelvis BofAinda não há avaliações

- App P2Documento26 páginasApp P2Khamron BridgewaterAinda não há avaliações

- L5 - Special SensesDocumento39 páginasL5 - Special SensesNana Boakye Anthony AmpongAinda não há avaliações

- Taste BudsDocumento7 páginasTaste BudsTURARAY FRANCES MERLENEAinda não há avaliações

- Reading Comprehension Passage 1 - The Meaning and Power of SmellDocumento1 páginaReading Comprehension Passage 1 - The Meaning and Power of SmellAsad HasanAinda não há avaliações

- Physiology of Smell and Taste-MyDocumento46 páginasPhysiology of Smell and Taste-MyHamid Hussain HamidAinda não há avaliações

- Bio OhDocumento3 páginasBio OhEmmaAinda não há avaliações

- Molecular Gastronomy Used in BakeryDocumento64 páginasMolecular Gastronomy Used in Bakerysmyrna_exodus100% (1)

- Odour TasteDocumento6 páginasOdour TasteJOHANNAH MARIE TOMASAinda não há avaliações

- JasonRoss Smell 0Documento5 páginasJasonRoss Smell 0Victor_Brujan_2831Ainda não há avaliações

- Lesson 2 Physiological and Psychological Foundationsof Sensory FunctionDocumento33 páginasLesson 2 Physiological and Psychological Foundationsof Sensory FunctionAnh MaiAinda não há avaliações

- Anatomy Skin Receptors, Taste and Smell Nov 4th 2016Documento23 páginasAnatomy Skin Receptors, Taste and Smell Nov 4th 2016HollyAinda não há avaliações

- Physiology of Taste: Taste Receptor Cells, Taste Buds and Taste NervesDocumento4 páginasPhysiology of Taste: Taste Receptor Cells, Taste Buds and Taste NerveskeerpngAinda não há avaliações

- Sensory Evaluation 2017-2018Documento126 páginasSensory Evaluation 2017-2018Kimlong KaoAinda não há avaliações

- Disorders of Taste and Smell ImageDocumento10 páginasDisorders of Taste and Smell Imageडा. सत्यदेव त्यागी आर्यAinda não há avaliações

- Module 5 - PhysioDocumento4 páginasModule 5 - PhysioTwisha SaxenaAinda não há avaliações

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocumento3 páginasReview of Related Literature and StudiesCharlie LesgonzaAinda não há avaliações

- Sensory Evaluation and AnalysisDocumento83 páginasSensory Evaluation and Analysisampoloquiozachary4Ainda não há avaliações

- The Olfactory Symphony - Exploring The Biology of The Human NoseDocumento2 páginasThe Olfactory Symphony - Exploring The Biology of The Human NoseYienAinda não há avaliações

- Sensory Testing Process DetailsDocumento40 páginasSensory Testing Process DetailsMario JiménezAinda não há avaliações

- Comm 1 ReadingsDocumento4 páginasComm 1 ReadingsJoar BaseAinda não há avaliações

- OdorDocumento16 páginasOdorRobin TimkangAinda não há avaliações

- Scent 07102020Documento4 páginasScent 07102020OrsiAinda não há avaliações

- 07.03.2024 Real Exam PassageDocumento5 páginas07.03.2024 Real Exam Passagehitter.acute0nAinda não há avaliações

- (Q2) Electrochemistry 29th JulyDocumento21 páginas(Q2) Electrochemistry 29th JulySupritam KunduAinda não há avaliações

- Skye Menu 2022Documento8 páginasSkye Menu 2022Muhammad Rizki LaduniAinda não há avaliações

- Aluminum Alloy 6351 T6 Sheet SuppliersDocumento10 páginasAluminum Alloy 6351 T6 Sheet Supplierssanghvi overseas incAinda não há avaliações

- EOCR 종합 EN 2015 PDFDocumento228 páginasEOCR 종합 EN 2015 PDFShubhankar KunduAinda não há avaliações

- Air Cooler With Checking DoorDocumento2 páginasAir Cooler With Checking DoorSuraj KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Sorsogon State College Engineering & ArchitectureDocumento11 páginasSorsogon State College Engineering & ArchitectureArianne Mae De Vera GallonAinda não há avaliações

- Paper 2 Phy 2019-2023Documento466 páginasPaper 2 Phy 2019-2023Rocco IbhAinda não há avaliações

- JCB R135 & R155-HD Skid Steer-New BrochureDocumento8 páginasJCB R135 & R155-HD Skid Steer-New BrochureAshraf KadabaAinda não há avaliações

- HP Prodesk 400 G6 Microtower PC: Reliable and Ready Expansion For Your Growing BusinessDocumento4 páginasHP Prodesk 400 G6 Microtower PC: Reliable and Ready Expansion For Your Growing BusinessPằngPằngChiuChiuAinda não há avaliações

- Surface & Subsurface Geotechnical InvestigationDocumento5 páginasSurface & Subsurface Geotechnical InvestigationAshok Kumar SahaAinda não há avaliações

- Planetary Characteristics: © Sarajit Poddar, SJC AsiaDocumento11 páginasPlanetary Characteristics: © Sarajit Poddar, SJC AsiaVaraha Mihira100% (11)

- Phase-Locked Loop Independent Second-Order Generalized Integrator For Single-Phase Grid SynchronizationDocumento9 páginasPhase-Locked Loop Independent Second-Order Generalized Integrator For Single-Phase Grid SynchronizationGracella AudreyAinda não há avaliações

- Reproduction WorksheetDocumento5 páginasReproduction WorksheetJENY VEV GAYOMAAinda não há avaliações

- Nav Bharat Nirman: Indispensable Ideas For Green, Clean and Healthy IndiaDocumento4 páginasNav Bharat Nirman: Indispensable Ideas For Green, Clean and Healthy IndiaRishabh KatiyarAinda não há avaliações

- Cot 3Documento16 páginasCot 3jaycel cynthiaAinda não há avaliações

- Rockwell Allen BradleyDocumento73 páginasRockwell Allen BradleymaygomezAinda não há avaliações

- Ohms LawDocumento16 páginasOhms Lawmpravin kumarAinda não há avaliações

- Vanilla Farming: The Way Forward: July 2019Documento6 páginasVanilla Farming: The Way Forward: July 2019mituAinda não há avaliações

- Power Stations Using Locally Available Energy Sources: Lucien Y. Bronicki EditorDocumento524 páginasPower Stations Using Locally Available Energy Sources: Lucien Y. Bronicki EditorAmat sapriAinda não há avaliações

- Planet Earth: Its Propeties To Support LifeDocumento27 páginasPlanet Earth: Its Propeties To Support LifegillianeAinda não há avaliações

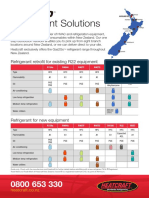

- Refrigerant Solutions: Refrigerant Retrofit For Existing R22 EquipmentDocumento2 páginasRefrigerant Solutions: Refrigerant Retrofit For Existing R22 EquipmentpriyoAinda não há avaliações

- The Relaxation Solution Quick Start GuideDocumento17 páginasThe Relaxation Solution Quick Start GuideSteve DiamondAinda não há avaliações

- Research Papers On Climate Change Global WarmingDocumento4 páginasResearch Papers On Climate Change Global Warminggw1nm9nbAinda não há avaliações

- Module 1 Hvac Basics Chapter-1Documento5 páginasModule 1 Hvac Basics Chapter-1KHUSHBOOAinda não há avaliações

- Sarason ComplexFunctionTheory PDFDocumento177 páginasSarason ComplexFunctionTheory PDFYanfan ChenAinda não há avaliações

- Sunday Afternoon, October 27, 2013: TechnologyDocumento283 páginasSunday Afternoon, October 27, 2013: TechnologyNatasha MyersAinda não há avaliações