Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Chapter5 Conclusion

Enviado por

chaitu14388Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Chapter5 Conclusion

Enviado por

chaitu14388Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Chapter 5

CONCLUSION

In this chapter, I give my views on the whole idea of interlinking. Thereafter, I give an alternative solution to the water problem in case the plan of networking does not come true as per the wishful thinking of the president and the Task Force. Anyone who knows what river systems are, what inter-basin transfers bring forth, and the politics and economics of large river valley and inter-basin projects, will know that whatever water this plan holds is but a mirage. Prior experience teaches that we must study basic aspects of each river basin, including catchment area treatment, command area development, benchmark survey of the affected population, impacts of the reservoir and canal system on farmers, and fisheries, and public health. Environmental Impact Assessment will be inevitable. Compensatory and mitigated plans must be rationally conceived. Where the canal network extends, the surveyors must assess that whether soil is irrigable through surface water flows without water logging and salinisation that has taken a million hectares of Indian Land. The impacts on food security already in crisis will be disastrous because of a sudden change in cropping pattern. The River Valley Guidelines (1983) discuss environmental and social impacts due to transfer of water and people beyond suitability. Unless these guidelines become part of the project planning, the impacts will neither be considered nor be dealt with. Some questions that come to my mind are: 1. Will such a linking of rivers actually prevent drought? Or merely transfer drought? 2. What will be the extent of displacement, and provisions for rehabilitation? Canals also displace. In the Sardar Sarovar project, 1,50,000 landholders stand to lose land due to the canal network, of whom 23,500 will lose more than 25% of their land, and 2,000 will become landless. None is considered project-affected or eligible for rehabilitation. The whole crisis of water management today is due to total neglect of water harvesting, either because it is considered peripheral or to be a non-replicable, non-profitable micro-level experiment. Therefore we see the destruction of cultures, communities, and ecosystems, creating conflicts between states, as in Cauvery, and between state and people, as in Narmada. Conflicts are dealt with more politically than scientifically. If this happens in just one river basin, imagine the consequences across several river basins. Interstate disputes could take decades to resolve. The canals, designed for carrying irrigation waters rather than large peak flows, will not be sufficient to control or divert floods in the northern states but will transfer silt. Several large dams built to provide the head and storage required to supply the canals will permanently submerge fertile lands, forests, village communities and towns, leaving millions of people displaced or dispossessed. Interlinking Himalayan and peninsular rivers is budgeted at Rs. 5.6 lakh crore, even before the completion of feasibility studies, expected by 2008, at a cost of 150 crore. The point to be considered is that: Have alternatives been assessed? When pending water projects require Rs. 80,000 crore to be completed and made usable as per Parliamentary Committee report, is such a plan viable, scientific, or democratic? There is no time, space, or process indicated for participation of communities whose riparian rights must be considered, and who face upstream impacts, which are now known, and lesser-known downstream impacts. Annual Irrigation budgets of state governments are about 1000 crore each. From where will the money for inter-linking rivers come even if states pool resources for the next several decades? The local irrigation projects of the true and tested kind have kept India self-sufficient. In this ambiguous experiment of Inter-linking Rivers, India itself is the guinea pig. The 73rd amendment of the Indian Constitution direct that people's consent and consultation cannot be sidelined. Rivers support millions of people. A grandiose scheme such as interlinking would be likely to involve international lending agencies.

It will be nothing short of criminal if water is not treated properly and the water crisis worsens. Already Shivnath river in Chattisgarh is privatized, and the contractor has snatched away people's right even to drinking water. People of the country deserve to know if this centralized plan will nationalize the water only to privatize it like other national public property like oil, gas, land or mineral resources. In nature what is linked are not rivers but water itself, through the hydrological cycle. A balanced water cycle demands a holistic policy that promotes forest cover, prevents erosion, enhances ground water through micro-watershed structures, and provides for desiltation and maintenance of existing tanks, lakes and reservoirs. A vigilant judiciary should punish corrupt administrations for non-implementation of environmental regulations, right to life and livelihood.

Stated below is an alternative to the grandiose plan of networking major rivers of India. Alternative to the proposed plan of interlinking of rivers in India Proponents of river interlinking say that there is no alternative even though some of them concede that decentralized schemes for water harvesting can work locally but not at national level. This is precisely where the logic of decentralization applies, because each State is nothing but many "locals" and the nation consists of States. Local water systems are viable in isolation since they simply conserve as much as possible of the rainfall precipitated within their own boundaries. Shortage of water is simplistically seen as increase in demand without taking into account the very serious problems of distribution anomalies, obvious wastage and profligate consumption of water, which is a limited resource. As in the electric power sector, the thinking of planners appears to be that the only way of solving water shortage problems is to increase the quantity of water supplied to meet demand. This view does not recognize two factors. 1. Even though there may be an overall shortage of water, the reason for the seriousness of the problem is primarily improper distribution and vast differential in consumption, including leakages and consumer wastages. 2. If water is collected and used where it falls as rain (by rainwater harvesting from roof-tops and open areas in urban areas and check dams or johars and soak pits in rural areas), and the run-off made to naturally or artificially percolate into the ground, the local demand for water can be met locally to a great extent. Such measures will also check soil loss by erosion by encouraging green cover. The second factor has actually made hitherto dry seasonal rivers to flow (as demonstrated in Rajasthan by Rajendra Singh of Tarun Bharat Sangh, by M.S.N.Reddy in Mylanahalli near Tiptur in Tumkur District of Karnataka and elsewhere) and increase the flow in perennial rivers. Also, as the late Anil Agarwal demonstrated conclusively, ten reservoirs each of 1 hectare catchment area can store more water than a single dam with 10 hectares of catchment area. That is, decentralization of water collection and storage will provide better availability of water than huge dams and lengthy canal systems. Action based on the above two factors will cost vastly less in terms of finance and more importantly, cost almost nothing in terms of the ill effect of projects on people since local people will take local action for their own benefit. Planning for decentralized water availability also practically obviates displacement of people and acquisition of land, and makes for better local cooperation within and between communities instead of competition for scarce resources that are the basic reason for tensions. Thus the two factors briefly explained above are a clear alternative to the current thinking on interlinking rivers with a network of numerous dams and lengthy canals that have very high initial capital cost, very high operating and maintenance costs, and social and environmental ill effects and political fall-outs. Certain suggestions: 1. The task force should make the details of feasibility reports public for scrutiny.

2. The task force should invite discussions over the networking of rivers from all states and be open to accept suggestions of experts from all fields.

Você também pode gostar

- Insights Into Editorial: A Flood of Questions: ContextDocumento2 páginasInsights Into Editorial: A Flood of Questions: ContextSweta RajputAinda não há avaliações

- ILR Booklet - Printable FormatDocumento8 páginasILR Booklet - Printable FormatSangeetha SriramAinda não há avaliações

- Insights Into Editorial Make The Link Indian River Linking IRL ProjectDocumento2 páginasInsights Into Editorial Make The Link Indian River Linking IRL ProjectMohit VashisthAinda não há avaliações

- I Nternational Journal of Computational Engineering Research (Ijceronline - Com) Vol. 2 Issue. 7Documento5 páginasI Nternational Journal of Computational Engineering Research (Ijceronline - Com) Vol. 2 Issue. 7International Journal of computational Engineering research (IJCER)Ainda não há avaliações

- Indian Interriver Linking An AnalysisDocumento5 páginasIndian Interriver Linking An AnalysisNithin ThomasAinda não há avaliações

- Interlinking of Rivers - Significance & Challenges - CivilsdailyDocumento7 páginasInterlinking of Rivers - Significance & Challenges - CivilsdailySantosh GuptaAinda não há avaliações

- M2019WPG008 - Summary of SummariesDocumento9 páginasM2019WPG008 - Summary of SummariesShanmugha PriyaAinda não há avaliações

- Water Science in India Hydrological Obscurantism Epw Jayanta Bandyopadhyay 2012Documento3 páginasWater Science in India Hydrological Obscurantism Epw Jayanta Bandyopadhyay 2012Bruno MenezesAinda não há avaliações

- Hydroelectric DamDocumento5 páginasHydroelectric Dammuhammad israrAinda não há avaliações

- Water Resource Management in IndiaDocumento30 páginasWater Resource Management in IndiaY. DuttAinda não há avaliações

- WATER IN CRISIS ArticleDocumento8 páginasWATER IN CRISIS Articleritam chakrabortyAinda não há avaliações

- Beneath The Water Resource CrisisDocumento2 páginasBeneath The Water Resource CrisisSamar SinghAinda não há avaliações

- National Water PolicyDocumento8 páginasNational Water PolicyMathimaran RajuAinda não há avaliações

- DRR Paper 0107Documento16 páginasDRR Paper 0107afreen.jbracAinda não há avaliações

- Cve 654 IwrmDocumento10 páginasCve 654 IwrmAremu OluwafunmilayoAinda não há avaliações

- Water Resource EconomicsDocumento245 páginasWater Resource Economicsmostafa_h_fayed100% (1)

- Catchment ManagementDocumento4 páginasCatchment ManagementSachitha RajanAinda não há avaliações

- Everything You Need to Know About India's Interlinking of Rivers ProjectDocumento8 páginasEverything You Need to Know About India's Interlinking of Rivers ProjectVicky MbaAinda não há avaliações

- REVIEW OF AGRICULTURE: An Alternative Draft for ConsiderationDocumento14 páginasREVIEW OF AGRICULTURE: An Alternative Draft for ConsiderationAsha ShivaramAinda não há avaliações

- LIVRO LOUCKS INTRODUÇÃO E CASOS Water Resource Systems Planning and ManagementDocumento3 páginasLIVRO LOUCKS INTRODUÇÃO E CASOS Water Resource Systems Planning and ManagementLaís MonteiroAinda não há avaliações

- Ken Betwa River Interlinking Pol - Geo PDFDocumento17 páginasKen Betwa River Interlinking Pol - Geo PDFNikkiAinda não há avaliações

- Inter Basin Water Transfer (IBWT) "-A Case Study On Krishna - Bhima StabilizationDocumento7 páginasInter Basin Water Transfer (IBWT) "-A Case Study On Krishna - Bhima StabilizationIJRASETPublicationsAinda não há avaliações

- Water Treatment ThesisDocumento90 páginasWater Treatment ThesisSanMiguelJheneAinda não há avaliações

- Case Studies (Water Harvesting) and Arid Rajasthan and Ralegan SiddhiDocumento11 páginasCase Studies (Water Harvesting) and Arid Rajasthan and Ralegan SiddhiAvanish PatilAinda não há avaliações

- IWRM Theory and Practice for Sustainable River UseDocumento19 páginasIWRM Theory and Practice for Sustainable River UseHocine KINIOUARAinda não há avaliações

- 1 - Interlinking of Rivers - 22, 26Documento19 páginas1 - Interlinking of Rivers - 22, 26Saurabh Kumar TiwariAinda não há avaliações

- LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR WATER RIGHTS IN INDIADocumento19 páginasLEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR WATER RIGHTS IN INDIALavina Edward JosephAinda não há avaliações

- 33009925Documento5 páginas33009925Bhumika TanwarAinda não há avaliações

- Why India's $168 Billion River-Linking Project Is A Disaster-In-WaitingDocumento7 páginasWhy India's $168 Billion River-Linking Project Is A Disaster-In-WaitingPrabhat ParidaAinda não há avaliações

- Acharya ReviewDocumento11 páginasAcharya ReviewAdolf HittlerAinda não há avaliações

- Environmental Impacts Large DamsDocumento11 páginasEnvironmental Impacts Large DamsSuchitra SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Env ProjectDocumento4 páginasEnv Projectgoli sowmyaAinda não há avaliações

- Hydro EngineeringDocumento5 páginasHydro EngineeringAce WoodsAinda não há avaliações

- India's Water Crisis: Conserve Traditional Water BodiesDocumento15 páginasIndia's Water Crisis: Conserve Traditional Water BodiesSharmila DeviAinda não há avaliações

- India's Gigantic River Linking Project: Think About The Oceans Too! Sudhirendar SharmaDocumento2 páginasIndia's Gigantic River Linking Project: Think About The Oceans Too! Sudhirendar Sharmanaveen_k2004Ainda não há avaliações

- Negotiating Water Rights in Contexts of Legal Pluralism: Priorities For Research and ActionDocumento19 páginasNegotiating Water Rights in Contexts of Legal Pluralism: Priorities For Research and ActiontolandoAinda não há avaliações

- Literature Review NewDocumento10 páginasLiterature Review Newapi-549142880Ainda não há avaliações

- H2OSPLYDocumento36 páginasH2OSPLYPat BomilleAinda não há avaliações

- WRE IntroductionDocumento15 páginasWRE IntroductionKalidas A KAinda não há avaliações

- The Mullaperiyar Inter-Basin Water Transfer, Water Con Icts, and Dam SafetyDocumento54 páginasThe Mullaperiyar Inter-Basin Water Transfer, Water Con Icts, and Dam SafetyArun ArunAinda não há avaliações

- Ce 2031 Water Resources EngineeringDocumento30 páginasCe 2031 Water Resources EngineeringManikandan.R.KAinda não há avaliações

- CRRT Summary EngDocumento2 páginasCRRT Summary EngdmugundhanAinda não há avaliações

- WUMP ReportDocumento10 páginasWUMP Reportgeokhan02Ainda não há avaliações

- National Water Policy - 1987Documento11 páginasNational Water Policy - 1987Sumit Srivastava100% (1)

- Seminar Course Report: TOPIC-Water Law & Policy in 21 CenturyDocumento16 páginasSeminar Course Report: TOPIC-Water Law & Policy in 21 Centuryरायबली मिश्रAinda não há avaliações

- Water DemocracyDocumento107 páginasWater Democracyjade_rpAinda não há avaliações

- Pipe Dreams: Urban Wastewater Treatment For Biodiversity ProtectionDocumento18 páginasPipe Dreams: Urban Wastewater Treatment For Biodiversity ProtectionAkar TunjangAinda não há avaliações

- Question One:Answere. Conflict in The Water ResourcesDocumento5 páginasQuestion One:Answere. Conflict in The Water ResourcesBavaria Latimore BLAinda não há avaliações

- PaniDocumento5 páginasPaniTariqul Islam TareqAinda não há avaliações

- National Water Policy 1987Documento12 páginasNational Water Policy 1987Sachin WarghadeAinda não há avaliações

- Stream Shed Development Proposal for Attappady BlockDocumento15 páginasStream Shed Development Proposal for Attappady BlockRohitAinda não há avaliações

- Strem Shed Development ReportDocumento15 páginasStrem Shed Development ReportRohitAinda não há avaliações

- Ifp - 17010125053 - Naman KhannaDocumento13 páginasIfp - 17010125053 - Naman KhannaNaman KhannaAinda não há avaliações

- Dams: Achieving Human EquityDocumento18 páginasDams: Achieving Human EquityelrajilAinda não há avaliações

- MullaperiyarDocumento53 páginasMullaperiyarTony George PuthucherrilAinda não há avaliações

- Be Project ReportDocumento47 páginasBe Project Reportkhalique demonAinda não há avaliações

- Groundwater Prospecting: Tools, Techniques and TrainingNo EverandGroundwater Prospecting: Tools, Techniques and TrainingAinda não há avaliações

- Rehabilitation and Resettlement in Tehri Hydro Power ProjectNo EverandRehabilitation and Resettlement in Tehri Hydro Power ProjectAinda não há avaliações

- Ideal Pharma Facility DesignDocumento22 páginasIdeal Pharma Facility DesignMuqeet KazmiAinda não há avaliações

- Cases of Wild LifeDocumento12 páginasCases of Wild LifeNaveen SihareAinda não há avaliações

- Combined Quizes 09-14-2013Documento647 páginasCombined Quizes 09-14-2013scribdpdfsAinda não há avaliações

- Interior Dept. Solicitor Memo On Dakota Access PipelineDocumento38 páginasInterior Dept. Solicitor Memo On Dakota Access PipelineShadowproof100% (1)

- How Our Perceptions Affect CommunicationDocumento4 páginasHow Our Perceptions Affect CommunicationahAinda não há avaliações

- Group DynamicDocumento84 páginasGroup DynamicRahul SarinAinda não há avaliações

- Drainage basin: the area of land where surface water converges to a single pointDocumento8 páginasDrainage basin: the area of land where surface water converges to a single pointpianonobodyspecialAinda não há avaliações

- Bajura Technical ViewDocumento2 páginasBajura Technical ViewAnonymous ZhVoIIAinda não há avaliações

- 10eco CommandmentsDocumento4 páginas10eco CommandmentsThomas FischerAinda não há avaliações

- Urban Infrastructure Project: Par 309 - Advanced Architectural Design Studio - IiiDocumento2 páginasUrban Infrastructure Project: Par 309 - Advanced Architectural Design Studio - IiiSenthil ManiAinda não há avaliações

- Waterqualityms1 160622094059 PDFDocumento64 páginasWaterqualityms1 160622094059 PDFKenneth_AlbaAinda não há avaliações

- Elevated Water Tank ComputationDocumento28 páginasElevated Water Tank ComputationAiron Kaye SameloAinda não há avaliações

- Networks Out Comes (1997) Mario DianiDocumento19 páginasNetworks Out Comes (1997) Mario DianiRogel77Ainda não há avaliações

- Construction Project ManagementDocumento39 páginasConstruction Project ManagementsyikinAinda não há avaliações

- The Case of Water Supply at Sangitan Public Market Cabanatuan CityDocumento4 páginasThe Case of Water Supply at Sangitan Public Market Cabanatuan CityEldwin Jay L MonteroAinda não há avaliações

- Prezentacija Evidencija UlaganjaDocumento27 páginasPrezentacija Evidencija UlaganjaeHrvatskaAinda não há avaliações

- A Global EthicDocumento10 páginasA Global Ethicapi-265668222Ainda não há avaliações

- Rochedo Et Al-2018-Nature Climate ChangeDocumento5 páginasRochedo Et Al-2018-Nature Climate ChangeRaoni GuerraAinda não há avaliações

- The Third World War Will Be Fought ForDocumento3 páginasThe Third World War Will Be Fought ForNeha RastogiAinda não há avaliações

- Rio Declaration On Environment and DevelopmentDocumento5 páginasRio Declaration On Environment and DevelopmentJoseph Santos GacayanAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Development PillarsDocumento4 páginasSustainable Development PillarsMananMongaAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Form Monitoring Hand HygieneDocumento2 páginas10 Form Monitoring Hand Hygieneki jambronkAinda não há avaliações

- LWUA Operation and Maintenance Manual PDFDocumento433 páginasLWUA Operation and Maintenance Manual PDFRuby A. QuisayAinda não há avaliações

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: Docket No. 02-9484Documento6 páginasUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: Docket No. 02-9484Scribd Government DocsAinda não há avaliações

- PrelimsDocumento6 páginasPrelimsBierzo JomarAinda não há avaliações

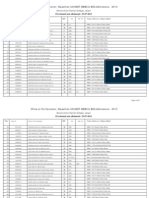

- Rajasthan UG NEET MBBS & BDS Admissions - 2013 Provisional seat allotmentsDocumento47 páginasRajasthan UG NEET MBBS & BDS Admissions - 2013 Provisional seat allotmentsAditya BhutraAinda não há avaliações

- By: Yusuf Misbahuddin NPM: 115130113Documento14 páginasBy: Yusuf Misbahuddin NPM: 115130113Yusuf MisbahuddinAinda não há avaliações

- Creative City Indicators: A FrameworkDocumento1 páginaCreative City Indicators: A FrameworkSalma AbouldahabAinda não há avaliações

- 1.nursing ManagementDocumento19 páginas1.nursing ManagementRajalakshmi Blesson0% (1)

- Placer Dome's Troubled History with Marcopper Mines in the PhilippinesDocumento5 páginasPlacer Dome's Troubled History with Marcopper Mines in the PhilippinesEdzel MuhiAinda não há avaliações