Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Mandela: Greatest Man Now Living

Enviado por

Malawi2014Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Mandela: Greatest Man Now Living

Enviado por

Malawi2014Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Mandela: greatest man now living by Mzati Nkolokosa, 06 December 2006 Statesmen can not be wished into existence.

The world is longing for one to unit e Iraq. And, as Iraqis are finding out, that man is not a citizen of the war tor n country but a South African. Mzati Nkolokosa writes: South Africa will, in the coming years, host two global events: the 2010 World C up and the funeral of Nelson Mandela. Both events will attract thousands of people, thousands of journalists. Across t he earths 24 time zones, millions will interrupt their waking or sleeping schedul es to gather around television sets. The World Cup is held once in four years and might come back to South Africa in the next five decades. The funeral of Mandela will be once and that is all. Tens of thousands will stand along roads to say farewell as he will be driven the st reets on his last journey to the resting place. Powerful men and women of the world will be at the funeral. They are people who can not go to a stadium to watch football: presidents like Hamid Karzai, George W Bush and Colonel Muammar Gaddafi; brilliant minds like Secretary of State Cond oleeza Rice and journalist Fareed Zakaria, former professor of political science at Harvard University, now editor of Newsweek International, who reports for an d oversees weekly production of eight editions of the magazine. These people will be on reserved seats because of protocol. But if Mandela had a chance, he could have reserved the choicest seats for the ordinary people becau se it was for such that he took the road of a freedom fighter. Thoughts of a funeral are awkward to some. But life is a journey and it comes to an end. The world is now busy reading the journey of Mandela which everyone wan ts to go on and on and on. Sadly, nature demands that Mandelas life, like all human beings, be over some day . At 88 [90], he is looking forward to that day. It would be very egotistical of me to say how I would like to be remembered, he sa id in March 1997. I would leave that entirely to South Africans. I would just lik e a simple stone on which is written Mandela. Mandela talks about his death. He does not talk about his funeralthat is up to So uth Africans. In fact, he spends time thinking about the afterlife as he hinted in one interview. When he dies, he said, and once in the next world, I will look for and join an ANC branch. Not that he is obsessed with party politics but the man is committed to freedom and justice and sees the ANC as the practical tool to fight oppression, for that is what he has been doing for most part of his life and perhaps fears oppressio n in the next life. The British Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, describes Mandela as not j ust the greatest statesman but the greatest man now living. Brown was writing in a November 13 special edition celebrating 60 years of Time Atlantic, years the magazine has coveredor, put rightly, uncoveredheroes. Of the m agazines 66 heroes, Mandela was the first and was given two pages. Space is scarc e in print media and goes with the value of a story. Of course, three others were given two pages: the Beatles, Mikhail Gorbachev and Princess Diana. But Mandelas story was the first. The best comes first in almost all media. This, again, speaks volumes of the value placed on this great son of Africa. Mandela had all reasons to hate white South Africans. He had all the reasons to call them strangers and violently chase them from South Africa. But after 27 years of imprisonment at the hands of the apartheid government, Man dela chose truth and reconciliation, not revenge. He had been separated from his wife, to whom he wrote lovely letters; he missed his children. He went through the pain of being unable to bury his mother and his first born son Madiba Thembe

kile, deaths that made Mandela to look back at his younger self, to evaluate his life. Her [the mothers] difficulties, her poverty, made me question once again whether I had taken the right path, wrote Mandela in his book, Long Walk to Freedom. For a long time, my mother had not understood my commitment to the struggle. In such times, some people put up a brave face as if they have survived shame an d embarrassment, but it is the soul that is bruised; the heart, not the body. This was the case with Mandela. Questions without answers can be more painful th an physical torture. Mandela wondered, without any answer, why his family was pu t in such an awkward situation. For long he had advised people not to worry about things they could not control. I was unable to take my own advice, he says. I had many sleepless nights. The separation from his family resulting from a court case using discriminatory laws was enough to warrant a revenge after his release on Sunday, February 11, 1 990. Yet there were more challenges after his release from prison. He realised he had gained his freedom but he was yet to fight for the freedom of his people. Once the Inkatha members secretly raided the Vaal township of Boipatong and killed 46 people. No arrests were made. It was as if some people had no state protection. Mandela, give us guns, said placards carried by his supporters at one rally. Victor y through battle, not talk. He had been tested for too long to carry on the struggle peacefully. But he said peace. It was because of the greatness of Mandelaand, especially, his refusal to hate or become embitteredthat a multiracial South Africa was born, not in further bloodsh ed and catastrophe, but in peace and democracy, said Brown. To understand the importance of Mandela, consider Iraq, that helpless, failed st ate where sectarian violence has more control than the government of Prime Minis ter Nouri al-Maliki. Hundreds are dying everyday. No one is safe, not even the P rime Minister. Aparism Ghosh is Time senior correspondent who has been reporting from Baghdad s ince the fall of Saddam Hussein. Ghosh knows life in the city. He has the experi ence of flying into Baghdad, too. I know what lies ahead, he says of flights from Amman in Jordan to Baghdad. It is an hours uneventful flying, followed by the worlds scariest landinga steep, co rkscrewing plunge into what used to be Saddam Hussein International Airport. It is scariest because the pilot has to avoid being shot down by Iraqi insurgent s. The plane stays at 30,000 feet until it is directly over Baghdad airport, the n take a spiralling dive, straightening up yards from the runway. If you are looking out the window, it can feel as if the plane is in a free fall from which it cant possibly pull out, says Ghosh. I have learned from experience to ask for an aisle seat. That is not all. The journey from the airport into Baghdad is a 14-kilometre dri ve on what is called the Highway of Death. The Shiites and Sunnis are engaged in sectarian violence. In fact, sectarian vio lence is a political term. Iraq is in a civil war. Out-going United Nations Secr etary General Kofi Annan called the violence worse than a civil war in a BBC inter view on Monday. Sunni leader Saleh al-Mutlak has repeatedly told the press that Iraqs political l andscape has no giants. Not only that, he said earlier this year, but the political system we have created makes it impossible for such a figure to emerge. Politicians in Iraq have discovered that the easiest way to win votes is to appe al to sectarian chauvinism; they have little incentive to take the higher, more difficult road of liberal democracy which cherishes reason, liberty and freedom. In July this year, al-Mutlak said Iraq could be united and the killings could co me to an end. The country, he said, needed an Iraqi Mandela. This is the gigantic size of Mandela. Even those in Iraq know the sectarian viol enceor civil war, to be precisecan be ended by a leader of Mandelas calibre; not Ge orge W Bush or Tony Blair, the so-called champions of democracy; not the Pope; b

ut Nelson Mandela from South Africa, a two-hour flight from Blantyre in Malawi. Mandela was born on July 18, 1918, and spent early childhood the traditional, ol d way in Mvezo, a tiny village on the banks of the Mbashe River in Umtata. From an early age, I spent most of my free time in the veld playing and fighting with the other boys of the village, he wrote in his autobiography. Childhood lessons have a tendency to remain in people for life. They are lessons guarded by society which, sadly, are not cherished by the modern society of Mal awi. Now socialisation or transmission of values is, in some cases, more from the ele ctronic media (television, radio and internet) and housemaids than the family. Children ought to play with toys made by themselves. Children ought to play with clay to derive lessons from the natural world: let them run in the rain until i ts over (this does not cause malaria, the disease is caused by plasmodium transm itted by the female anopheles mosquito); let them play with clay and realise the ir skills. In such engagement with nature, Mandela found virtues that make him. The statesm anship in Mandela can be traced back to about five years of age when he shared f ood and blanket with others. He had become a herd-boy, looking after sheep and calves in the fields where he learned hunting. One day, his turn came to ride a donkey and it bolted into a bu sh of thorns. He was embarrassed. I learned that to humiliate another person is to make him suffer an unnecessarily cruel fate. Even as a boy, I defeated my opponents without dishonouring them, he says. You can see more from a mountain and from the perspective of years, says a brill iant journalist Jon Meacham. Mandela has climbed mountains and lived a long life . He joined politics while studying in Johannesburg by joining the African Nationa l Congress in 1942. He has climbed mountains of books and time. He has been a li fe transformed from violence to peace. Yet he believes that when all channels of peaceful protest fail, violence is a practical option. This is what he did by l eading Umkhonto we Sizwe, a military arm of the ANC. Mandela has walked from the violent extreme of the world, balancing up on the wa y, and reached the peaceful end of life. He has shown that the end is more impor tant than the beginning. Former president Bakili Muluzi missed that lesson. Fred rick Chiluba of Zambia missed the crucial aspect as well. The years Mandela was locked up in his cell during daylight hours, deprived him of music and sunshine. He was denied things from outside. The familiar things we take for granted are what we miss most. But the character in him remained intac t. The discipline is still in him. He wakes up by 4: 30 am even if he went to bed late. He makes his bedhe still bel ieves this is his duty, even when he was president. He exercises for one hour fr om 5 am and takes breakfast at 6: 30 am as he reads the days newspapers. This daily timetable is changing now. Age is catching up and everything is becom ing slower. Yet his voice, weak and faint, is more important than ever. He prefers we to I. Thus he attributes all the honour given him to South Africans, saying that a man see n by all is standing on his peoples shoulders. Mandela is now reflecting on his life and enjoying his childhood best momentstypi cal of old age. His greatest pleasure is watching the sun set with the music of Handel or Tchaikovsky playing. He should really love that for he is the sun of the world, light for hidden, dar k corners of poverty, disease, oppression and dictatorship. It is now the turn of the world to enjoy watching the setting of Mandelas life wh ich is at the end of the horizon. He will go a happy man after leading the first South African multiracial governm ent for five years, leaving the presidency at his peaka lesson many have failed t o learn. Mandela worked with his immediate predecessor Fredrick de Klerk who was invited into a government of national unity. Further, Mandela has worked with his immedi

ate successor President Thabo Mbeki. The three formed a team that went to Fifa headquarters in Zurich, Switzerland, t o make South Africas case to host the 2010 World Cup. South Africa is now gearing for the World Cup. The OR Tambo International Airpor t is being expanded and renovated. There is a plancontroversial thoughto dig an un derground train tunnel between Johannesburg and Pretoria. The fever is growing stronger everyday. The economy benefits are visible. But th e world does not know what will come first: the World Cup or the funeral of Mand ela. Share your thoughts on Mandela and the story with the author at mzatinews@yahoo. com

Você também pode gostar

- Statement JBDocumento4 páginasStatement JBMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Electoral Laws FinalDocumento169 páginasElectoral Laws FinalMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Public Notice Phase 8 StatisticsDocumento3 páginasPublic Notice Phase 8 StatisticsMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Projected Figures For 2013 Voter Registration Malawi PDFDocumento119 páginasProjected Figures For 2013 Voter Registration Malawi PDFMalawi Electoral CommissionAinda não há avaliações

- Chairman Speech During Presentation (MALE CANDIDATES)Documento6 páginasChairman Speech During Presentation (MALE CANDIDATES)John Richard KasalikaAinda não há avaliações

- Registration of Voters - Phases (Revised)Documento1 páginaRegistration of Voters - Phases (Revised)Malawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Malawi Elections 2014 - AnalysisDocumento3 páginasMalawi Elections 2014 - AnalysisMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Chairman Speech Helen SinghDocumento5 páginasChairman Speech Helen SinghMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Transforming Malawi Together - It Is Possible (Nzotheka) : People'S Party Manifesto 2014-2019Documento92 páginasTransforming Malawi Together - It Is Possible (Nzotheka) : People'S Party Manifesto 2014-2019Malawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- National Voter Registration StatisticsDocumento235 páginasNational Voter Registration StatisticsMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Press Release Registration Statistics Phase 6 PDFDocumento4 páginasPress Release Registration Statistics Phase 6 PDFMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- MEC Electoral Calendar - Revised 8 Nov 2013Documento10 páginasMEC Electoral Calendar - Revised 8 Nov 2013Malawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Malawi Elections 2014 - Electoral CalendarDocumento7 páginasMalawi Elections 2014 - Electoral CalendarMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Registration Centres Phase 4Documento15 páginasRegistration Centres Phase 4Malawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Registration of Voters PhasesDocumento1 páginaRegistration of Voters PhasesMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

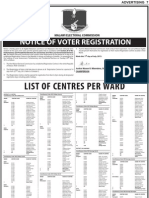

- Notice of Voter Registration: List of Centres Per WardDocumento13 páginasNotice of Voter Registration: List of Centres Per WardMalawi2014100% (1)

- Brochure - Kulembetsa Mayina Mkaundula Wa Voti Phase 1Documento2 páginasBrochure - Kulembetsa Mayina Mkaundula Wa Voti Phase 1Malawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Registration Centres Phase TwoDocumento14 páginasRegistration Centres Phase TwoMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Malawi Cabinet 1july2013Documento4 páginasMalawi Cabinet 1july2013Malawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- 2013-14 Budget StatementDocumento37 páginas2013-14 Budget StatementMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Scottish Parliament Speech President BandaDocumento11 páginasScottish Parliament Speech President BandaMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Press Release - Review of Indicative Limits On Travel Allowances in MalawiDocumento2 páginasPress Release - Review of Indicative Limits On Travel Allowances in MalawiMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- ICT Week ICT 4 Democracy KuntiyaDocumento7 páginasICT Week ICT 4 Democracy KuntiyaMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Ward Councillor and MP Roles and Responsibilities 2014 TripartiteDocumento2 páginasWard Councillor and MP Roles and Responsibilities 2014 TripartiteMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Full Inquiry Report Into Bingu Wa Mutharika's DeathDocumento105 páginasFull Inquiry Report Into Bingu Wa Mutharika's DeathJohn Richard KasalikaAinda não há avaliações

- Imagine : Will You Be One of Them?Documento5 páginasImagine : Will You Be One of Them?Malawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Scottish Parliament Speech President BandaDocumento11 páginasScottish Parliament Speech President BandaMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- ICT Week Mobile Technology KuntiyaDocumento8 páginasICT Week Mobile Technology KuntiyaMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Malawi Political Market Performance ReportDocumento4 páginasMalawi Political Market Performance ReportMalawi2014Ainda não há avaliações

- Chasowa ReportDocumento84 páginasChasowa ReportJohn Richard Kasalika100% (3)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Apolinario MabiniDocumento2 páginasApolinario MabiniDannyFernandez50% (2)

- Stillwell's Command ProblemsDocumento538 páginasStillwell's Command ProblemsBob Andrepont100% (1)

- Saint Vincent de Paul Diocesan College: Mangagoy, Bislig CityDocumento2 páginasSaint Vincent de Paul Diocesan College: Mangagoy, Bislig CityBernard Jayve PalmeraAinda não há avaliações

- Oxford Journals - Jazz Influence On French Music PDFDocumento17 páginasOxford Journals - Jazz Influence On French Music PDFFederico Pardo CasasAinda não há avaliações

- America's Sherlock Holmes - The Legacy of William Burns (PDFDrive)Documento262 páginasAmerica's Sherlock Holmes - The Legacy of William Burns (PDFDrive)Wayne MartinAinda não há avaliações

- PVAO Citizens CharterDocumento26 páginasPVAO Citizens CharterLyn EscanoAinda não há avaliações

- Weather Weapons Dark World of Environmental WarfareDocumento28 páginasWeather Weapons Dark World of Environmental WarfareMarshall IslandsAinda não há avaliações

- Undergraduate Prospectus 2013Documento104 páginasUndergraduate Prospectus 2013吴衍德Ainda não há avaliações

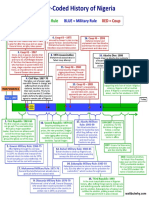

- Nigeria History3 PDFDocumento1 páginaNigeria History3 PDFViraj PanaraAinda não há avaliações

- Audio Scripts - Practice Test 2 PDFDocumento8 páginasAudio Scripts - Practice Test 2 PDFWilliam PasiniAinda não há avaliações

- Economic Espionage: A Framework For A Workable Solution: Mark E.A. DanielsonDocumento46 páginasEconomic Espionage: A Framework For A Workable Solution: Mark E.A. DanielsonmiligramAinda não há avaliações

- Gaze HeuristicDocumento25 páginasGaze HeuristicLeonardo SimonciniAinda não há avaliações

- Total War TroyDocumento2 páginasTotal War TroyJemmy MartonoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 22Documento5 páginasChapter 22api-235651608Ainda não há avaliações

- Big Book of Kaiju 01 - Kaiju of The LandDocumento21 páginasBig Book of Kaiju 01 - Kaiju of The LandBoracchio Pasquale100% (1)

- M M Alam - in Loving Memory Of.Documento4 páginasM M Alam - in Loving Memory Of.BTghazwa100% (3)

- 1984 Unit Plan: Course: Grade 10 English Course Code: ENG2DDocumento18 páginas1984 Unit Plan: Course: Grade 10 English Course Code: ENG2DAna Ximena Trespalacios SilvaAinda não há avaliações

- Blended Learning Lesson PlanDocumento4 páginasBlended Learning Lesson Planapi-458892729Ainda não há avaliações

- WWII Spitfire MK2 Powerplant AnalysisDocumento14 páginasWWII Spitfire MK2 Powerplant AnalysisConstantin CrispyAinda não há avaliações

- Legend of The Five Rings Form Fillable Character Sheet 5EDocumento2 páginasLegend of The Five Rings Form Fillable Character Sheet 5EKrieger NgAinda não há avaliações

- Nimrod ReportDocumento1.064 páginasNimrod Reportnelsontoyota100% (1)

- F-35 Climatic Chamber Testing & System VerificationDocumento20 páginasF-35 Climatic Chamber Testing & System VerificationDavid VươngAinda não há avaliações

- Art and Money Laundering - MILES MATHISDocumento13 páginasArt and Money Laundering - MILES MATHISFranco D. VicoAinda não há avaliações

- WWII 43rd Infantry DivisionDocumento100 páginasWWII 43rd Infantry DivisionCAP History Library100% (3)

- Cruz 2003 Phil International Law Book PDFDocumento131 páginasCruz 2003 Phil International Law Book PDFSweet Zel Grace PorrasAinda não há avaliações

- What's Inside: The Division of Poland and Start of World War IIDocumento33 páginasWhat's Inside: The Division of Poland and Start of World War IIÁlvaro Sánchez100% (1)

- Silent Invasion - China - S Influence in AustraliaDocumento367 páginasSilent Invasion - China - S Influence in Australiaa random guy100% (4)

- Camp David and the Secret Underground Site RDocumento24 páginasCamp David and the Secret Underground Site RgenedandreaAinda não há avaliações

- Zeng GuofanDocumento5 páginasZeng Guofanrquin9Ainda não há avaliações

- The Soviets - The Russian Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers Councils 1905-1921Documento357 páginasThe Soviets - The Russian Workers, Peasants, and Soldiers Councils 1905-1921danuler100% (1)