Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

History: Acute Mesenteric Ischemia (AMI) Is A Syndrome in Which

Enviado por

Alexis Nacionales AguinaldoDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

History: Acute Mesenteric Ischemia (AMI) Is A Syndrome in Which

Enviado por

Alexis Nacionales AguinaldoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

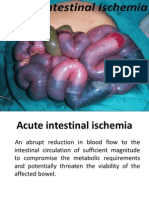

Acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a syndrome in which inadequate blood flow through the mesenteric circulation causes ischemia

and eventual gangrene of the bowel wall. Broadly, AMI may be classified either as arterial or venous disease. Arterial disease may be subdivided into nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI; see the image below) and occlusive mesenteric arterial ischemia (OMAI). OMAI may be further subdivided into acute mesenteric arterial embolus (AMAE) and acute mesenteric arterial thrombosis (AMAT). Venous disease takes the form of mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT). Thus, for practical purposes, AMI comprises 4 different primary clinical entities: NOMI, AMAE, AMAT, and MVT.

superior mesenteric vein (SMV), which joins the splenic vein to form the portal vein. AMI arises primarily from problems in the SMA circulation or its venous outflow. Collateral circulation from the CA and IMA may allow sufficient perfusion if flow in the SMA is reduced because of occlusion, a low-flow state (eg, NOMI), or venous occlusion. The IMA seldom is the site of lodgment of an embolus. Because of its smaller lumen, only small emboli can enter this vessel. When lodgment occurs, the embolus lodges at the site where the IMA divides into the left colic, sigmoidal, and superior hemorrhoidal arteries. In such instances, collateral flow from the middle colic and middle hemorrhoidal arteries (through the vascular arcades of the IMA distal to the embolus) may sustain the perfusion of the left colon.

History

To some extent, all types of acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) present similarly. Differences in clinical appearance for each type are discussed below. The most important finding is pain that is disproportionate to physical examination findings. Typically, pain is moderate to severe, diffuse, nonlocalized, constant, and sometimes colicky. Onset varies from type to type. Nausea and vomiting are found in 75% of affected patients. Anorexia and diarrhea progressing to obstipation are also common. Abdominal distention and gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding are the primary symptoms in as many as 25% of patients. Pain may be unresponsive to narcotics. As the bowel becomes gangrenous, rectal bleeding and signs of sepsis (eg, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, fever, altered mental status) develop. A review of systems, looking for risk factors of AMI, should be performed. This syndrome has a catastrophic outcome if not properly and rapidly treated. It should be considered in any patient with abdominal pain disproportionate to physical findings, gut emptying in the form of vomiting or diarrhea, and the presence of risk factors, especially age older than 50 years.

CT scan (with contrast) of nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia with resulting bowel wall edema (arrows).

The 4 types of AMI have somewhat different predisposing factors, clinical pictures, and prognoses. A secondary clinical entity of mesenteric ischemia occurs because of mechanical obstruction, such as internal hernia with strangulation, volvulus, intussusception, tumor compression, and aortic dissection. Occasionally, blunt trauma may cause isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and lead to intestinal infarction. Because the 4 types of AMI share many similarities and a final common pathway (ie, bowel infarction and death, if not properly treated), they are discussed together. In 1930, Cokkinis remarked, Occlusion of the mesenteric vessels is apt to be regarded as one of those conditions of which the diagnosis is impossible, the prognosis hopeless, and the treatment almost useless.[1] This quote indicates some of the extreme difficulties faced by physicians treating AMI. Symptoms are nonspecific initially, before evidence of peritonitis presents. Thus, diagnosis and treatment are often delayed until the disease is advanced. Fortunately, since 1930, many advances have been made that allow earlier diagnosis and treatment. Whereas the prognosis remains grave for patients in whom the diagnosis is delayed until bowel infarction has already occurred, patients who receive the appropriate treatment in a timely manner are much more likely to recover.[2] Typically, the celiac artery (CA) supplies the foregut, hepatobiliary system, and spleen; the SMA supplies the midgut (ie, small intestine and proximal mid colon); and the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) supplies the hindgut (ie, distal colon and rectum).[3] However, multiple anatomic variants are observed. Venous drainage is through the

Embolic acute mesenteric ischemia

AMI from embolic causes typically has the most abrupt and painful presentation of all types, as a consequence of the rapid onset of occlusion and the inability to form additional collateral circulation. It has been described as abdominal apoplexy and can be labeled as a bowel attack." Often, vomiting and diarrhea (gut emptying) are observed. Patients are usually found to have a source of embolization. Because most emboli are of cardiac origin, patients often have atrial fibrillation or a recent myocardial infarction (with mural thrombus). Infrequently, patients may report a history of valvular heart disease or previous embolic episode.

Thrombotic acute mesenteric ischemia

AMI caused by a thrombus typically happens when an artery already partially blocked by atherosclerosis becomes completely occluded. As with myocardial infarction preceded by angina pectoris, 20-50% of patients with thrombotic AMI have a history of abdominal angina. Abdominal angina is a syndrome of postprandial abdominal pain that starts soon after eating and lasts for up to 3 hours. The digestion of food requires increased perfusion of the intestine, so the mechanism is similar to that of exercise-induced angina pectoris. Weight loss, food fear, early satiety, and altered bowel habits may be present. The precipitating event that initiates thrombotic AMI may be a sudden drop in cardiac output from myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure (CHF) or a ruptured plaque. Dehydration from vomiting or diarrhea due to an unrelated illness may also precipitate thrombotic AMI. These patients have undergone a gradual progression of arterial occlusion and frequently have a better collateral supply. Bowel viability is better preserved, often leading to a less severe presentation than with embolic AMI. Symptoms tend to be less intense and of more gradual onset. As might be expected, these patients typically have a history of atherosclerotic disease at other sites, such as coronary artery disease, cerebral arterial disease, peripheral artery disease (especially aortoiliac occlusive disease), or a history of aortic reconstruction.

a prolonged period with gradual worsening. The chronic form may manifest as esophageal variceal bleeding. Many patients have a history of 1 or more of risk factors for hypercoagulability. These include oral contraceptive use, congenital hypercoagulable states, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), liver disease, tumor, and portocaval surgery.

Diagnostic Considerations

Because acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) is a condition with an unclear initial presentation, serious morbidity, and a high mortality rate without proper treatment, clinical suspicion should remain high. Obtain early angiography if any suspicion of AMI exists. Subsequent treatment should be initiated as rapidly as possible. No patient in whom AMI is suspected should be discharged unless AMI can be ruled out. Consider a diagnosis of AMI in all elderly patients with abdominal pain, especially if the pain is disproportionate to physical examination findings. Patients with atrial fibrillation, cardiovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease, especially those with recent myocardial infarction, are at higher risk. Other conditions to consider include the following: Ovarian torsion Small bowel obstruction Volvulus of midgut Splenic vein thrombosis

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) occurs more frequently in older patients than other forms of AMI do. Often, these elderly patients are already in an intensive care unit (ICU) with acute respiratory failure or severe hypotension from cardiogenic or septic shock, or they are taking vasopressive drugs. Most of them are taking digitalis. Symptoms typically develop over several days, and patients may have had a prodrome of malaise and vague abdominal discomfort. When infarction occurs, the clinical condition of the ICU patient deteriorates with no apparent reason. Patients may report increased pain associated with vomiting. They may become hypotensive and tachycardic, with loose bloody stool.

Pathophysiology

Insufficient perfusion of the small bowel and colon may result from arterial occlusion by embolus or thrombosis (AMAE or AMAT), thrombosis of the venous system (MVT), or nonocclusive processes such as vasospasm or low cardiac output (NOMI). Embolic phenomena account for approximately 50% of all clinical cases, arterial thrombosis for about 25%, NOMI for roughly 20%, and MVT for less than 10%. Rarely, isolated spontaneous dissections of the SMA have been reported.[4, 5, 6, 7] Hemorrhagic infarction leading to perforation is the common pathologic pathway whether the occlusion is arterial or venous. Injury severity is inversely proportional to the mesenteric blood flow and is influenced by the number of vessels involved, systemic mean blood pressure, duration of ischemia, and collateral circulation. The superior mesenteric vessels are involved more frequently than the inferior mesenteric vessels, with blockage of the latter often being silent because of better collateral circulation. Damage to the affected bowel portion may range from reversible ischemia to transmural infarction with necrosis and perforation. The injury is complicated by reactive vasospasm in the SMA region after the initial occlusion. Arterial insufficiency causes tissue hypoxia, leading to initial bowel wall spasm. This leads to gut emptying by

Mesenteric venous thrombosis

Mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) is often observed in a much younger patient population than other types of AMI are. MVT patients can present with an acute or subacute abdominal pain syndrome related to involvement of the small intestine rather than the colon. The symptoms are frequently less dramatic. Diagnosis can be even more difficult, because symptoms may have been present for weeks (ie, 27% have symptoms for >30 d). Typical symptoms of MVT may have been experienced for

vomiting or diarrhea. Mucosal sloughing may cause bleeding into the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. At this stage, little abdominal tenderness is present, producing the classic intense visceral pain that is disproportionate to physical examination findings. As the ischemia persists, the mucosal barrier becomes disrupted, and bacteria, toxins, and vasoactive substances are released into the systemic circulation. This can cause death from septic shock, cardiac failure, or multisystem organ failure before bowel necrosis actually occurs. As hypoxic damage worsens, the bowel wall becomes edematous and cyanotic. Fluid is released into the peritoneal cavity; this explains the serosanguineous fluid sometimes recovered by diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Bowel necrosis can occur in 8-12 hours from the onset of symptoms. Transmural necrosis leads to peritoneal signs and heralds a much worse prognosis. Embolic AMI (AMAE) is usually caused by an embolus of cardiac origin. Typical causes include mural thrombi after myocardial infarction, atrial thrombi associated with mitral stenosis and atrial fibrillation, vegetative endocarditis, mycotic aneurysm, and thrombi formed at the site of atheromatous plaques within the aorta or at the sites of vascular aortic prosthetic grafts interposed anywhere between the heart and the origin of the SMA. The vascular occlusion is sudden, so the patients have not developed a compensatory increase in collateral flow. As a result, they experience worse ischemia than patients with thrombotic AMI. The SMA is the visceral vessel most susceptible to emboli because of its small take-off angle from the aorta and higher flow. Most often, emboli lodge about 6-8 cm beyond the arterial origin, at a narrowing near the emergence of the middle colic artery. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Injury Center, a special form of mesenteric ischemia may result from systemic air embolism in those who sustain high-energy blast injuries. These patients sustain severe primary blast injury to the lung, a condition referred to as blast lung. Thrombotic AMI (AMAT) is a late complication of preexisting visceral atherosclerosis. Symptoms do not develop until 2 of the 3 arteries (usually the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries) are stenosed or completely blocked. Progressive worsening of the atherosclerotic stenosis before the acute occlusion allows time for development of additional collateral circulation. Most patients with thrombotic AMI have atherosclerotic disease at other sites, such as coronary artery disease, stroke, or peripheral arterial disease. A drop in cardiac output from myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure (CHF) may cause AMI in a patient with visceral atherosclerosis. Thrombotic AMI may also be a complication of arterial aneurysm or other vascular pathologies, such as dissection, trauma, and thromboangiitis obliterans. In

inflammatory vascular disease, smaller vessels are affected. Thrombosis tends to occur at the origin of the SMA, causing widespread infarction. These patients frequently present with a history of chronic mesenteric ischemia in the form of intestinal angina before the emergent event. NOMI is precipitated by a severe reduction in mesenteric perfusion, with secondary arterial spasm from such causes as cardiac failure, septic shock, hypovolemia, or the use of potent vasopressors in patients in critical condition. Because bowel perfusion, similar to cerebral perfusion, is preserved in the setting of hypotension, NOMI represents a failure of autoregulation. Many vasoactive drugs (eg, digitalis, cocaine, diuretics, and vasopressin) may also cause regional vasoconstriction. Gross pathologic arterial or venous occlusions are not observed. MVT often (ie, >80% of the time) is the result of some processes that make the patient more likely to form a clot in the mesenteric circulation (ie, secondary MVT). Primary MVT occurs in the absence of any identifiable predisposing factor. MVT may also occur after ligation of the splenic vein for a splenectomy or ligation of the portal vein or the superior mesenteric vein as part of damage control surgery for severe penetrating abdominal injuries. Other associated causes include pancreatitis, sickle cell disease, and hypercoagulability caused by malignancy. MVT often affects a much younger population. Symptoms may be present longer than in the typical cases of AMI, sometimes exceeding 30 days. Infarction from MVT is rarely observed with isolated SMV thrombosis, unless collateral flow in the peripheral arcades or vasa recta is compromised as well. Fluid sequestration and bowel wall edema are more pronounced than in arterial occlusion. The colon is usually spared because of better collateral circulation. The chronic form of SMV thrombosis may manifest as esophageal variceal bleeding.

Etiology

Causes of embolic AMI (AMAE) include the following: Cardiac emboli - Mural thrombus after myocardial infarction, auricular thrombus associated with mitral stenosis and atrial fibrillation, septic emboli from valvular endocarditis (less frequent) Emboli from fragments of proximal aortic thrombus due to a ruptured atheromatous plaque Atheromatous plaque dislodged by arterial catheterization Causes of thrombotic AMI (AMAT) include the following: Atherosclerotic vascular disease (most common) Aortic aneurysm Aortic dissection Arteritis Decreased cardiac output from myocardial infarction or CHF (thrombotic AMI may cause acute decompensation) Dehydration from other causes Causes of NOMI include the following:

Hypotension from CHF, myocardial infarction, sepsis, aortic insufficiency, severe liver or renal disease, or recent major cardiac or abdominal surgery Vasopressive drugs Ergotamines Cocaine Digitalis (whether digitalis use causes NOMI or patients who develop NOMI are older and are more likely to have been prescribed digitalis is unclear) Causes of MVT include the following (>80% of patients with MVT are found to have predisposing conditions): Hypercoagulability from protein C and S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency, dysfibrinogenemia, abnormal plasminogen, polycythemia vera (most common), thrombocytosis, sickle cell disease, factor V Leiden mutation, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive use Tumor causing venous compression or hypercoagulability (paraneoplastic syndrome) Infection, usually intra-abdominal (eg, appendicitis, diverticulitis, or abscess) Venous congestion from cirrhosis (portal hypertension) Venous trauma from accidents or surgery, especially portocaval surgery Increased intra-abdominal pressure from pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic surgery[8] Pancreatitis Decompression sickness

Sexual differences in incidence

No overall sex preference exists for AMI. Men might be at higher risk for occlusive arterial disease because they have a higher incidence of atherosclerosis. Conversely, women who are on oral contraceptives or are pregnant are at higher risk of MVT.

Racial differences in incidence

No racial predilections are known for AMI. However, people of races with a higher rate of conditions leading to atherosclerosis, such as black people, might be at higher risk.

Prognosis

The prognosis of AMI of any type is grave. Overall, the mortality rate in the last 15 years from all causes of AMI averages 71%, with a range of 59-93%. Once bowel wall infarction has occurred, the mortality rate is as high as 90%. Even with good treatment, up to 50-80% of patients die. Survivors of extensive bowel resection face significant long-term morbidity because of the reduced intestinal mucosal surface available for absorption. However, with rapid treatment, the mortality rate can be reduced considerably, and patients may be spared bowel resection. In a report from Madrid of 21 patients with SMA embolus with little delay in initiating maximal treatment, intestinal viability was achieved in 100% of patients if the duration of symptoms was shorter than 12 hours, 56% if it was 12-24 hours, and only 18% if it was longer than 24 hours. Early recognition and treatment of NOMI has been shown to reduce the mortality rate to 50-55%. Symptomatic MVT has a 30-day mortality rate of 13-15%. A long-term follow-up study of 31 patients who had surgery and survived the acute episode, revealed 2- and 5-year survival rates of 70% and 50%. Deaths were mainly related to cardiovascular comorbidity and malignant disease. With appropriate anticoagulation, only 1 patient died after a recurrent attack of arterial mesenteric thrombosis.

Epidemiology

United States statistics

The overall prevalence of AMI is 0.1% of all hospital admissions; this figure may be expected to rise as the population ages. The exact prevalence of MVT is unknown because many cases are presumed to be limited in symptomatology and to resolve spontaneously. In 1989, the incidence of diagnosed MVT was reported to be 2 cases per 100,000 admissions over 20 years at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine Montefiore Medical Center.

International statistics

Outside of the United States, reported rates of AMI are probably lower in countries with limited diagnostic capability or whose populations have a shorter life expectancy because AMI is primarily a disease of older individuals.

Patient Education

Educate patients who survive to discharge about shortbowel syndrome. Educate surviving patients about the importance of taking warfarin or other discharge medications to prevent recurrence. For patient education resources, see the Environmental Exposures and Injuries Center, as well as The Bends Decompression Syndromes.

Age-related differences in incidence

AMI is frequently considered a disease of people older than 50 years. Younger people with atrial fibrillation or risk factors for MVT, such as oral contraceptive use or hypercoagulable states (eg, those caused by protein C or S deficiency), may present with AMI.

Approach Considerations

Recognition of acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) before permanent tissue damage occurs is the best way to improve patient survival, and only angiography or exploratory surgery makes early diagnosis possible. Experience with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is rapidly changing the

therapeutic approach, allowing prompt laparotomy in patients with suspected AMI when expeditious formal angiography is not available. A second-look procedure is indicated whenever bowel of questionable viability is not resected. After initial medical or surgical stabilization, patients with AMI typically have a prolonged inpatient recovery time. This is especially true when resection of necrotic bowel is performed. Such patients may need to be kept on nil per os (NPO) status, and they may be maintained on parenteral nutrition for some time. If sepsis is evident, liver abscess should be actively sought. During the inpatient stay, every effort must be made to find and, if possible, treat any predisposing cause(s) of AMI. Inpatient medications include the following: Papaverine - For patients with arterial occlusive AMI or nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia (NOMI) Heparin - For patients who have mesenteric venous thrombosis (MVT) or have undergone revascularization Warfarin - For long-term treatment of patients with MVT or atrial fibrillation Broad-spectrum antibiotics and pain medications For all patients Thrombolytics - For selected patients with embolic AMI Because timing is essential in preventing bowel necrosis with its attendant severe morbidity and mortality, patients should be transferred only if the primary hospital lacks adequate services to diagnose and treat the patient. Patients should be optimally resuscitated before transfer. Appropriate services should be available at the receiving hospital. Some experience with percutaneous endovascular interventions has been accumulated. In select cases, especially in isolated spontaneous dissection of the SMA, stent placement may offer the best option.[11]

Infusion of papaverine and thrombolytics

Papaverine infused through the angiography catheter at the affected vessel is useful for all arterial forms of AMI. It relieves reactive vasospasm in occluded arterial vessels and is the only treatment of NOMI other than resection of gangrenous bowel. Start an infusion of 30-60 mg/h after angiography, and adjust the dose for clinical response. Continue this for at least 24 hours. If the catheter slips into the aorta, significant hypotension can occur. Papaverine is incompatible with heparin. Thrombolytics infused through the angiography catheter can be a life-saving therapy for selected patients with embolic AMI. Bleeding is the main complication. Thrombolytic administration is risky and should only be undertaken if peritonitis or other signs of bowel necrosis are absent. The infusion must be started within 8 hours of symptom onset. If symptoms do not improve within 4 hours or if peritonitis develops, stop the infusion and perform surgery.

Angioplasty after thrombolysis

A very select group of patients who have atherosclerotic plaques at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) after thrombolysis is eligible for angioplasty. Angioplasty is technically difficult because of the anatomy of the SMA. Restenosis rates are 20-50%. Limited study findings indicate a definite role for angioplasty in the treatment of AMI. A case of successful transcutaneous catheter aspiration of an SMA embolic clot was reported from the Czech Republic.[12]

Heparin anticoagulation

Heparin anticoagulation is the main treatment of MVT. If no signs of bowel necrosis exist, the patient may not even need an operation. Heparin may increase the chance of bleeding complications. A possible avenue of study for future clinical trials is the use of enoxaparin or other lowmolecular-weight heparins as a potential substitute for heparin in the treatment of MVT. Administer heparin as a bolus of 80 U/kg, not to exceed 5000 U, and then as an infusion at 18 U/kg/h until full conversion to oral warfarin. Appropriate monitoring of anticoagulation using activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) is mandatory.

Initial Treatment

Resuscitation

Every effort should be made to improve patients cardiovascular status. Vasopressors should be avoided, because they worsen ischemia. Oxygen should be provided to maintain a saturation between 96-99%, by endotracheal intubation if needed. Fluid resuscitation is accomplished with isotonic sodium chloride solution, and blood products are provided as needed. Adequacy of resuscitation can be monitored by urinary output, central venous pressure, or Swan-Ganz pressure monitoring. Insert a nasogastric tube, and optimize cardiac status by treating arrhythmia, congestive heart failure (CHF), or myocardial infarction. Start broad-spectrum antibiotics early. Provide pain control while maintaining stable blood pressure.

Surgical Care

Before operative management of AMI, stabilize patients by means of intravenous (IV) fluid administration, antibiotic prophylaxis covering the colonic flora, nasogastric tube decompression, and bladder catheterization, with heparin or papaverine administered as indicated. Blood should be available. In all types of AMI, resection of necrotic bowel may be required if signs of peritonitis develop. Differentiation of

nonviable from viable bowel can be enhanced by intraoperative fluorescein administration. During laparotomy, 1 g of fluorescein is infused. Viable bowel fluoresces brightly under a Wood lamp, thus allowing the surgeon to better evaluate the segments that need resection. Because of fat absorption, fluorescein can be used only once. Most patients can benefit from a 24- to 48-hour second-look operation to assess for viability of the remaining bowel. Intraoperative fluorescein administration may be performed either at the primary operation or during the second-look operation.

Spontaneous dissection of superior mesenteric artery

When spontaneous dissection of the SMA is diagnosed before the onset of intestinal infarction, percutaneous stent placement has been successful.

Activity Restriction

Patients activities are dictated by their conditions. Bed rest to allow for monitoring and to reduce demand on cardiac output is balanced against ambulation to prevent DVT.

Prevention

Aside from timely diagnosis and treatment of predisposing conditions, there are no known preventive measures for AMI. In the presence of a clinical syndrome suggesting chronic mesenteric insufficiency, color Doppler evaluation of the mesenteric vessels may help identify at-risk patients for further workup and identify those who might need angioplasty

Embolic acute mesenteric ischemia

For embolic AMI, unless the involved bowel is clearly gangrenous, an attempt at reperfusion is necessary. The SMA is isolated, and the location of the blockage is determined by palpation of pulses. Because most emboli are near the origin of the middle colic artery, note the proximal SMA pulse in embolic AMI. A transverse arteriotomy is made proximal to the point of occlusion, and a balloon-tipped Fogarty catheter (size 3 or 4) is passed distally. The balloon is then inflated and the clot extracted. The arteriotomy can be closed primarily or vein-patched to prevent lumen compromise. A bypass may be required if thrombectomy is unsuccessful. Observe the intestines for 10-15 minutes after restoration of flow to assess viability of bowel. This can be enhanced by intraoperative duplex ultrasonography, fluorescein use, and palpation of pulses distal to the occlusion.

Medication Summary

Drug types employed in the treatment of acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI) include vasodilators, thrombolytics, anticoagulants, antibiotics, and analgesics. Withhold therapeutic drugs (except analgesics and prophylactic antibiotics) until the type of AMI present has been determined by means of computed tomography (CT) scanning or angiography.

Thrombotic acute mesenteric ischemia

For thrombotic AMI, emergency surgical revascularization is indicated. Simple thrombectomy has little or no benefit, because most patients have clinically significant atherosclerosis at the time of the acute decompensation. Unlike patients with embolic AMI, these patients have a lesion at the origin of the SMA, and no SMA pulsation is detected at the origin. If the gut is not gangrenous, proceed with revascularization. An antegrade aortomesenteric bypass is the best technique. Transaortic endarterectomy is an alternative when no vein is suitable for harvesting or when a prosthetic graft is contraindicated (eg, with massive fecal contamination).[13] After revascularization and thrombectomy, reevaluate bowel viability.

Mesenteric venous thrombosis

For patients with MVT, as for any patient with AMI and signs of peritonitis, including diagnosed NOMI, exploratory laparotomy and resection of infarcted bowel is indicated. Thrombectomy has little use in MVT, because it can only be performed if the thrombus is fresh (ie, no more than 1-3 days old). Thrombectomy has little proven effectiveness in this setting, because the thrombus is usually too widespread and all the thrombi cannot be removed completely.

Você também pode gostar

- Mesentericischemia: A Deadly MissDocumento10 páginasMesentericischemia: A Deadly MisspakausAinda não há avaliações

- Acute intestinal ischemia causes and symptomsDocumento50 páginasAcute intestinal ischemia causes and symptomsRohit ParyaniAinda não há avaliações

- Abdominal Vascular Emergency 2016Documento13 páginasAbdominal Vascular Emergency 2016Medicina 42Ainda não há avaliações

- Vascular Disease of The BowelDocumento28 páginasVascular Disease of The BowelOlga GoryachevaAinda não há avaliações

- Vasculer Anomly of IntestineDocumento38 páginasVasculer Anomly of Intestineعبد الله مازن موسى عبدAinda não há avaliações

- Ischemia BowelDocumento36 páginasIschemia BowelTammie YoungAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Mesenteric Ischemia: A Case Report and ReviewDocumento40 páginasAcute Mesenteric Ischemia: A Case Report and ReviewTsega WesenAinda não há avaliações

- Mesenteric Ischemia ReviewDocumento12 páginasMesenteric Ischemia Reviewmaria arenas de itaAinda não há avaliações

- Abdominal ImagingDocumento16 páginasAbdominal Imagingfrancu60Ainda não há avaliações

- Acute Mesenteric Arterial OcclusionDocumento28 páginasAcute Mesenteric Arterial OcclusionJaime Jose Ortiz Andrade100% (2)

- Abdominal Emergencies in The Geriatric Patient 2014Documento8 páginasAbdominal Emergencies in The Geriatric Patient 2014Jose CabralesAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Mesenteric IschemiaDocumento20 páginasAcute Mesenteric IschemiasolysanAinda não há avaliações

- Mesenteric Ischemia: The Whole Spectrum: M. J. SiseDocumento5 páginasMesenteric Ischemia: The Whole Spectrum: M. J. Siseanggitas2594Ainda não há avaliações

- Colonic Ischemia - UpToDateDocumento35 páginasColonic Ischemia - UpToDateWitor BelchiorAinda não há avaliações

- Mallory Weiss Syndrome - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento9 páginasMallory Weiss Syndrome - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDaniela EstradaAinda não há avaliações

- Mesentric IschemiaDocumento27 páginasMesentric IschemiaThe broken ringAinda não há avaliações

- Messenteric Ischemia Diagnosis and TreatmentDocumento13 páginasMessenteric Ischemia Diagnosis and TreatmentRemananAinda não há avaliações

- Mesentric IschemiaDocumento27 páginasMesentric Ischemiawalid ganodAinda não há avaliações

- AscitesascitesDocumento15 páginasAscitesascitesKevinJuliusTanadyAinda não há avaliações

- BWT Sken 4Documento82 páginasBWT Sken 4Eri PuspitaAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding Upper GI BleedingDocumento18 páginasAcute Gastrointestinal Bleeding Upper GI BleedingAldwin AyuyangAinda não há avaliações

- Diseases of The SmalllntestineDocumento183 páginasDiseases of The SmalllntestineIgor CemortanAinda não há avaliações

- Abdominal Aortic AneurysmDocumento20 páginasAbdominal Aortic AneurysmPortia Rose RodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- Cont Cardiac D SesDocumento58 páginasCont Cardiac D SesChristian Allen SibalaAinda não há avaliações

- Managing Acute Mesenteric Ischaemia: EditorialDocumento4 páginasManaging Acute Mesenteric Ischaemia: EditorialGdfgdFdfdfAinda não há avaliações

- Authors: Section Editor: Deputy EditorDocumento31 páginasAuthors: Section Editor: Deputy EditorRafaella GiácomoAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of The Adult With Abdominal Pain in The Emergency Department - UpToDateDocumento41 páginasEvaluation of The Adult With Abdominal Pain in The Emergency Department - UpToDateBryan Tam ArevaloAinda não há avaliações

- Portal Hypertension PDFDocumento12 páginasPortal Hypertension PDFissam_1994Ainda não há avaliações

- Uppergastrointestinalbleeding: Marcie Feinman,, Elliott R. HautDocumento11 páginasUppergastrointestinalbleeding: Marcie Feinman,, Elliott R. HautjoseAinda não há avaliações

- Diseases of The AortaDocumento48 páginasDiseases of The AortaYibeltal AssefaAinda não há avaliações

- How To Diagnose STEMI?Documento6 páginasHow To Diagnose STEMI?Adhie BadriAinda não há avaliações

- Myocardial Infarction: BackgroundDocumento9 páginasMyocardial Infarction: BackgroundNor Faizah Ahmad SadriAinda não há avaliações

- Lectura 8Documento8 páginasLectura 8Daniela Andrea Tello GuaguaAinda não há avaliações

- Mallory Weiss Syndrome-1 RevDocumento10 páginasMallory Weiss Syndrome-1 RevHuzlyAinda não há avaliações

- 7.30.08 Volk. Mesenteric IschemiaDocumento16 páginas7.30.08 Volk. Mesenteric Ischemiaowcordal7297Ainda não há avaliações

- Lec 6Documento13 páginasLec 6Hoth HothAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of causes and initial testing for ascitesDocumento16 páginasEvaluation of causes and initial testing for ascitesMaricruz BracamonteAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Coronary SyndromeDocumento45 páginasAcute Coronary SyndromeParsa EbrahimpourAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of The Adult With Abdominal Pain in The Emergency Department - UpToDateDocumento69 páginasEvaluation of The Adult With Abdominal Pain in The Emergency Department - UpToDateGiulio MilanezAinda não há avaliações

- Jurnal DinaDocumento11 páginasJurnal DinaRahma Puji LestariAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Coronary Syndrome - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocumento5 páginasAcute Coronary Syndrome - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfYe YulianAinda não há avaliações

- Acute AbdomenDocumento56 páginasAcute AbdomenponekAinda não há avaliações

- Bowel IschemiaDocumento79 páginasBowel IschemiaNovita AnjaniAinda não há avaliações

- Ascitis PDFDocumento17 páginasAscitis PDFLeonardo MagónAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of The Adult With Abdominal Pain in The Emergency department-UpToDateDocumento37 páginasEvaluation of The Adult With Abdominal Pain in The Emergency department-UpToDateAna Gabriela RodríguezAinda não há avaliações

- Evaluation of The Adult With Abdominal Pain in The Emergency Department UpToDateDocumento41 páginasEvaluation of The Adult With Abdominal Pain in The Emergency Department UpToDateLeonardo CastilloAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Acn-IiDocumento80 páginasNursing Acn-IiMunawar100% (6)

- Dijagnoza 1 PDFDocumento6 páginasDijagnoza 1 PDFSemir1989Ainda não há avaliações

- Bicol University College of Nursing: Danekka G. Tan BSN 4-CDocumento8 páginasBicol University College of Nursing: Danekka G. Tan BSN 4-CDanekka TanAinda não há avaliações

- HP Jan05 BleedDocumento5 páginasHP Jan05 BleedSyahanim IsmailAinda não há avaliações

- Case Alcohol Abuse and Unusual Abdominal Pain in A 49-Year-OldDocumento7 páginasCase Alcohol Abuse and Unusual Abdominal Pain in A 49-Year-OldPutri AmeliaAinda não há avaliações

- Ischemic Heart DiseaseDocumento47 páginasIschemic Heart DiseaseAbood SamoudiAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation 3Documento42 páginasPresentation 3Max ZealAinda não há avaliações

- Acute Coronary Syndrome: Aminah DalimuntheDocumento48 páginasAcute Coronary Syndrome: Aminah Dalimunthesintesis obatAinda não há avaliações

- Abd Pain Mimics Aug 31Documento15 páginasAbd Pain Mimics Aug 31Muhammad Arif RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- Pasmedicine 2019Documento183 páginasPasmedicine 2019Ibrahim FoondunAinda não há avaliações

- Utd 32654 Case - Reports AydinDocumento3 páginasUtd 32654 Case - Reports AydinDavid LopezAinda não há avaliações

- Lower GIT BleedingDocumento89 páginasLower GIT Bleedingمجاهد إسماعيل حسن حسينAinda não há avaliações

- Mesenteric Ischemia 1Documento11 páginasMesenteric Ischemia 1Manuel E. Niebles De AyoAinda não há avaliações

- Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Symptoms, Signs, and ManagementNo EverandMedian Arcuate Ligament Syndrome: Pathophysiology, Symptoms, Signs, and ManagementAinda não há avaliações

- Amp CR ModelDocumento1 páginaAmp CR ModelAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- Amp CR ModelDocumento1 páginaAmp CR ModelAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- Research Topic NG Nicu TeamDocumento1 páginaResearch Topic NG Nicu TeamAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- Dengue Protocol AgustinDocumento10 páginasDengue Protocol AgustinAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- Research Topic NG Nicu TeamDocumento1 páginaResearch Topic NG Nicu TeamAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- Types of HospitalsDocumento50 páginasTypes of HospitalsLynie Ann Perandos TanAinda não há avaliações

- 3 - Taping Technique ProtocolDocumento65 páginas3 - Taping Technique ProtocolAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- Dengue Protocol AgustinDocumento10 páginasDengue Protocol AgustinAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- OEA QuestionnaireTipsDocumento5 páginasOEA QuestionnaireTipsNanciaKAinda não há avaliações

- Cleansing Mechanism of SoapDocumento3 páginasCleansing Mechanism of SoapAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- HP PSC 1300 Series All-In-OneDocumento82 páginasHP PSC 1300 Series All-In-Oneankitgarg13Ainda não há avaliações

- Computation ReviewerDocumento1 páginaComputation ReviewerAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- CHF: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment of Congestive Heart FailureDocumento24 páginasCHF: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment of Congestive Heart FailureAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- 1001004Documento4 páginas1001004Alexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Tricks For Improving Your MemoryDocumento2 páginas10 Tricks For Improving Your MemoryAlexis Nacionales AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- Form Active Structure TypesDocumento5 páginasForm Active Structure TypesShivanshu singh100% (1)

- Vector 4114NS Sis TDSDocumento2 páginasVector 4114NS Sis TDSCaio OliveiraAinda não há avaliações

- Lab StoryDocumento21 páginasLab StoryAbdul QadirAinda não há avaliações

- WindSonic GPA Manual Issue 20Documento31 páginasWindSonic GPA Manual Issue 20stuartAinda não há avaliações

- OS LabDocumento130 páginasOS LabSourav BadhanAinda não há avaliações

- AVR Instruction Set Addressing ModesDocumento4 páginasAVR Instruction Set Addressing ModesSundari Devi BodasinghAinda não há avaliações

- October 2009 Centeral Aucland, Royal Forest and Bird Protecton Society NewsletterDocumento8 páginasOctober 2009 Centeral Aucland, Royal Forest and Bird Protecton Society NewsletterRoyal Forest and Bird Protecton SocietyAinda não há avaliações

- Dep 32.32.00.11-Custody Transfer Measurement Systems For LiquidDocumento69 páginasDep 32.32.00.11-Custody Transfer Measurement Systems For LiquidDAYOAinda não há avaliações

- Mil STD 2154Documento44 páginasMil STD 2154Muh SubhanAinda não há avaliações

- Display PDFDocumento6 páginasDisplay PDFoneoceannetwork3Ainda não há avaliações

- There Is There Are Exercise 1Documento3 páginasThere Is There Are Exercise 1Chindy AriestaAinda não há avaliações

- Felizardo C. Lipana National High SchoolDocumento3 páginasFelizardo C. Lipana National High SchoolMelody LanuzaAinda não há avaliações

- Dell Compellent Sc4020 Deploy GuideDocumento184 páginasDell Compellent Sc4020 Deploy Guidetar_py100% (1)

- Evil Days of Luckless JohnDocumento5 páginasEvil Days of Luckless JohnadikressAinda não há avaliações

- Srimanta Sankaradeva Universityof Health SciencesDocumento3 páginasSrimanta Sankaradeva Universityof Health SciencesTemple RunAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial 1 Discussion Document - Batch 03Documento4 páginasTutorial 1 Discussion Document - Batch 03Anindya CostaAinda não há avaliações

- 2021 JHS INSET Template For Modular/Online Learning: Curriculum MapDocumento15 páginas2021 JHS INSET Template For Modular/Online Learning: Curriculum MapDremie WorksAinda não há avaliações

- Revision Worksheet - Matrices and DeterminantsDocumento2 páginasRevision Worksheet - Matrices and DeterminantsAryaAinda não há avaliações

- TJUSAMO 2013-2014 Modular ArithmeticDocumento4 páginasTJUSAMO 2013-2014 Modular ArithmeticChanthana ChongchareonAinda não há avaliações

- New Hire WorkbookDocumento40 páginasNew Hire WorkbookkAinda não há avaliações

- Photosynthesis Lab ReportDocumento7 páginasPhotosynthesis Lab ReportTishaAinda não há avaliações

- 2010 HD Part Cat. LBBDocumento466 páginas2010 HD Part Cat. LBBBuddy ButlerAinda não há avaliações

- Letter From Attorneys General To 3MDocumento5 páginasLetter From Attorneys General To 3MHonolulu Star-AdvertiserAinda não há avaliações

- Fast Aldol-Tishchenko ReactionDocumento5 páginasFast Aldol-Tishchenko ReactionRSLAinda não há avaliações

- Journals OREF Vs ORIF D3rd RadiusDocumento9 páginasJournals OREF Vs ORIF D3rd RadiusironAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Analysis of Wipro LTDDocumento101 páginasFinancial Analysis of Wipro LTDashwinchaudhary89% (18)

- Public Private HEM Status AsOn2May2019 4 09pmDocumento24 páginasPublic Private HEM Status AsOn2May2019 4 09pmVaibhav MahobiyaAinda não há avaliações

- A Guide To in The: First AidDocumento20 páginasA Guide To in The: First AidsanjeevchsAinda não há avaliações

- Indian Standard: Pla Ing and Design of Drainage IN Irrigation Projects - GuidelinesDocumento7 páginasIndian Standard: Pla Ing and Design of Drainage IN Irrigation Projects - GuidelinesGolak PattanaikAinda não há avaliações

- Annual Plan 1st GradeDocumento3 páginasAnnual Plan 1st GradeNataliaMarinucciAinda não há avaliações