Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

A Written Report On The Manifestations of Filipino Nationalism During Japanese Period

Enviado por

Raeanne DavisDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Written Report On The Manifestations of Filipino Nationalism During Japanese Period

Enviado por

Raeanne DavisDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A Written Report on the Manifestations of Filipino Nationalism during Japanese Period Submitted By: Group 5 Submitted to: Mrs.

Rowena dela Pea

Introduction: World War II happened between Philippines and Japan. After the war between Spain and Philippines, America and Philippines, another war came in between Japan and Philippines. The invasion of the Philippines by Japanese is known as the most crucial period. It is the time to have faith in an individual and as a nation. A test of having a strong faith, justice and freedom in our country. Japanese are known as the cruelest colonial that has come in the Philippines. For the Filipinos who suffered under their leadership, it was very difficult to forget like a scar that never comes off. World War II subjected the indigenous people to a moral degradation from which they hardly ever recovered. Filipinos during that time suffered from unbearable pain, hunger, thirst. They would even force them to work without enough salary. It caused many Filipinos away from their loved ones and even caused death. Japan brought a scar on the land of Philippines during the war. But America was able to team-up with the Philippines and drove away the Japanese. At that time, Filipinos felt freedom. A freedom that would be treasured from generations to generations. Because we will never be afraid again to fight for our countrys freedom. Never again

Content: Japan launched a surprise attack on the Philippines on December 8, 1941, just ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Initial aerial bombardment was followed by landings of ground troops both north and south of Manila. The defending Philippine and United States troops were under the command of General Douglas MacArthur, who had been recalled to active duty in the United States Army earlier in the year and was designated commander of the United States Armed Forces in the Asia-Pacific region. The aircraft of his command were destroyed; the naval forces were ordered to leave; and because of the circumstances in the Pacific region, reinforcement and resupply of his ground forces were impossible. Under the pressure of superior numbers, the defending forces withdrew to the Bataan Peninsula and to the island of Corregidor at the entrance to Manila Bay. Manila, declared an open city to prevent its destruction, was occupied by the Japanese on January 2, 1942. The Philippine defense continued until the final surrender of United StatesPhilippine forces on the Bataan Peninsula in April 1942 and on Corregidor in May. Most of the 80,000 prisoners of war captured by the Japanese at Bataan were forced to undertake the infamous "Death March" to a prison camp 105 kilometers to the north. It is estimated that as many as 10,000 men, weakened by disease and malnutrition and treated harshly by their captors, died before reaching their destination. Quezon and Osmea had accompanied the troops to Corregidor and later left for the United States, where they set up a government in exile. MacArthur was ordered to Australia, where he started to plan for a return to the Philippines. The Japanese military authorities immediately began organizing a new government structure in the Philippines. Although the Japanese had promised independence for the islands after occupation, they initially organized a Council of State through which they directed civil affairs until October 1943, when they declared the Philippines an independent republic. Most of the Philippine elite, with a few notable exceptions, served under the Japanese. Philippine collaboration in Japanesesponsored political institutions--which later became a major domestic political issue--was motivated by several considerations. Among them was the effort to protect the people from the harshness of Japanese rule (an effort that Quezon himself had advocated), protection of family and personal interests, and a belief that Philippine nationalism would be

advanced by solidarity with fellow Asians. Many collaborated to pass information to the Allies. The Japanese-sponsored republic headed by President Jos P. Laurel proved to be unpopular. Japanese occupation of the Philippines was opposed by increasingly effective underground and guerrilla activity that ultimately reached largescale proportions. Postwar investigations showed that about 260,000 people were in guerrilla organizations and that members of the antiJapanese underground were even more numerous. Their effectiveness was such that by the end of the war, Japan controlled only twelve of the forty-eight provinces. The major element of resistance in the Central Luzon area was furnished by the Huks, Hukbalahap, or the People's AntiJapanese Army organized in early 1942 under the leadership of Luis Taruc, a communist party member since 1939. The Huks armed some 30,000 people and extended their control over much of Luzon. Other guerrilla units were attached to the United States Armed Forces Far East. MacArthur's Allied forces landed on the island of Leyte on October 20, 1944, accompanied by Osmea, who had succeeded to the commonwealth presidency upon the death of Quezon on August 1, 1944. Landings then followed on the island of Mindoro and around the Lingayen Gulf on the west side of Luzon, and the push toward Manila was initiated. Fighting was fierce, particularly in the mountains of northern Luzon, where Japanese troops had retreated, and in Manila, where they put up a lastditch resistance. Guerrilla forces rose up everywhere for the final offensive. Fighting continued until Japan's formal surrender on September 2, 1945. The Philippines had suffered great loss of life and tremendous physical destruction by the time the war was over. An estimated 1 million Filipinos had been killed, a large proportion during the final months of the war, and Manila was extensively damaged.

Japan attacks Pearl Harbor: December 7, 1941

Japan attacks Philippines: December 8, 1941

Bataan Death March: April 9, 1942

Content: FOR a people without experience of war, World War II came as the crucible for Filipinos, the ultimate test for the individual and the nation, a test of the effectiveness of the institutions of government and religion, a test of faith in truth, justice, and freedom, in fact a test of all the beliefs Filipinos subscribed to. The Japanese invasion in December 1941 had no precedent in the memory of most Filipinos of that period. The American invasion in 1898 had been a reality only to disparate groups in the country. The PhilippineAmerican War was not of a national character, having been limited to certain areas in Luzon and the Visayas, and was but endemic in nature in Mindanao. But World War II, which lasted from December 1941 until the last Japanese commander came down from the hills in August 1945, was a national experience the reality of which was felt by every Filipino of every age in every inhabited region of the archipelago. How did World War II affect the Filipinos, and how have the effects of war influenced Philippine life and civilization in thereafter? The occupation of the Philippines by Japanese forces in World War II led to at least two conditions that would have a permanent effect on the Filipino people. First, the occupation of the national territory by unfriendly alien troops ignited the resistance movement, bringing home to the people the obligation to defend their territory, and their acceptance of the need to sacrifice life and fortune to defend both territory and sovereignty. Second, the shortage of staples and commodities basic to a decent life in turn led to the degradation of the populace and the consequent deterioration of moral and ethical values, providing the foundation for a culture of corruption. To elaborate on the first condition, the occupation of their native earth by the interloper was a sore spot on the Filipino psyche. The Japanese did not seem to know this when they first stepped ashore, on December 10, 1941, simultaneously in Vigan, Ilocos Sur, and Atimonan, Tayabas. They would find out soon enough, obviously, to their everlasting woe, how sore a spot it was.

What may not have been anticipated either by the American allies, was the ferocity and intensity of the Filipino response to the invasion. All through the war years, from the realization of defeat as superior forces overran the country, to the final battle for liberation, the Filipinos waged a guerrilla war against the interloper with the incapacity to come to a truce. The guerrilla movement took root in every region, in every province of the Philippines, uniting people over differences of language, religion, culture, custom, and tradition. It was truly national in form and substance. The guerrilla movement had the strategic effect of tying down in the islands scores of Japanese infantry divisions that otherwise would have been used to invade other territory. How the Filipino resistance movement helped win World War II for the Allies has not been fully measured, but doubtless it was crucial to the Allied cause. It may have been decisive to ultimate victory. How decisive it was for the Filipino mind has not been fully measured either, for the guerrilla fighter became a permanent fixture on the Philippine scene. World War II came to an end, but the guerrilla war in the Philippines has raged to the present, although the fighters may now be fighting for or against certain causes the nature of which might confuse many Filipinos. The fact remains that the resistance against the Japanese during World War II united the Filipino people as no other factor would. It was the common cause that homogenized the nation as Jos Rizal could only dream of when he organized the Liga Filipina in 1892. No other cause brought the fragmented archipelago together as the resentment against the interloper did. Mountain dweller and city-bred, society scion and slum bum, Muslim and Christian, from Batanes to Sulu, they presented a united Filipino front, although they may have operated separately and independently of each other. This was the legacy of the holocaust. It created a new sense of Filipinohood. As to the second condition cited earlier, by its brutality and rapacity, by the bankruptcy of its values as an occupation force, by the subhuman conduct of its occupying troops, the Japanese in the Philippines during

World War II subjected the indigenous people to a moral degradation from which they hardly ever recovered. Barging into the scene with but poorly rationalized objectives which they failed to explain to the people, without the moral imperatives of the Spanish who vowed to bring Christ to the heathens alongside their armed forces, or the social philosophies of the Americans who purported to bring hygiene to the unwashed, the Japanese identified themselves to the subject peoples as no more than brigands out to rape and pillage, and therefore, clearly and unmistakably, as the enemy. So malevolent was the Japanese presence in these islands in World War II that the Filipinos devised an incredibly large repertoire of vengeful acts against this presence, ranging from expressions of ridicule and contempt by word or gesture to the unremitting guerrilla warfare that would forever scar the land. Any anti-Japanese word or deed was patriotic, therefore desirable; in fact, commendable. These acts would, in ordinary times, in their ordinary environment, and in the course of their ordinary lives, arouse opprobrium and censure from the average Filipino. But so mindless and devoid of conscience was the Japanese system, and so unaccommodating was the Filipino response, that those vengeful acts became accepted and, eventually, unhappily, ingrained in the collective morality of the people. Wartime conditions gave rise to the chronic shortages of basic commodities. The deprivation of physical comforts and the desperation with which the people regarded the situation which did not offer any element of hope, led people to acts that would have been considered reprehensible in any civilized community, but under the conditions many Filipinos now found themselves in, became mandatory, and in fact patriotic. Thus emerged the phenomenon of the saboteur, the vandal, the looter, and the profiteer who took advantage of scarcity to exact his toll, the squatter who sneered at all titles to property, and worst of all the traitor personified by the makapili who would betray any person and any cause, for lucre. These also became permanent in the Philippines, in business, politics, and every sector of the community.

The enemy ultimately collapsed in defeat and left the territory, but these phenomena would remain. The ruins caused by bomb and shell may be rebuilt, the harsh memories may dissipate, but the human detritus of a brutal war became part of the Philippine scene. These, then, are the lasting effects of the Filipino experience of World War II. The war as a political and military story has been adequately discussed by historians and analysts, but the scars of war etched on the national psyche have become part of the Filipino character. The debasement of the public morality and the confusion over questions of what is ethical, and the brave but often unfocused refusal to countenance foreign intrusion, has become part of the Filipino personality. Any effort to gain insight into the Filipino will have to consider these points.

Conclusion: World war II between Philippines and Japan made an unforgettable historical period in Philippines legacy. This war is a test of having great belief in one another; an individual and a nation. Sources: Wikipedia, philippinesfreepress.wordpress.com, philippinecountry.com Pictures on Google

Você também pode gostar

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Treaty of VersaillesDocumento3 páginasThe Treaty of Versailleselava94% (16)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- PESTLE Analysis - KenyaDocumento4 páginasPESTLE Analysis - KenyaJoseph0% (1)

- Urban Warfare Lesson PlanDocumento8 páginasUrban Warfare Lesson PlanDave WhitefeatherAinda não há avaliações

- Undaunted Reinforcements RulebookDocumento20 páginasUndaunted Reinforcements RulebookSantiago de la EsperanzaAinda não há avaliações

- The Horse Soldiers John WayneDocumento36 páginasThe Horse Soldiers John WayneF.M.NaidooAinda não há avaliações

- The Law of Armed Conflict International Humanitarian Law in War (Repost) PDFDocumento693 páginasThe Law of Armed Conflict International Humanitarian Law in War (Repost) PDFGeorge Hilal100% (3)

- Engr Doctrine PlacematDocumento1 páginaEngr Doctrine PlacematlucamorlandoAinda não há avaliações

- Japanese Occupation: Between 1941 and 1945Documento53 páginasJapanese Occupation: Between 1941 and 1945MCDABCAinda não há avaliações

- Application issues questionsDocumento3 páginasApplication issues questionsRaeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Application Issues ReportDocumento11 páginasApplication Issues ReportRaeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Presentation, Analysis and Interpretation of DataDocumento4 páginasPresentation, Analysis and Interpretation of DataRaeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- The Awareness of The Teenagers in Dealing With Crimes That Happen When They Commute in Concepcion Uno, Marikina CityDocumento3 páginasThe Awareness of The Teenagers in Dealing With Crimes That Happen When They Commute in Concepcion Uno, Marikina CityRaeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Sad Report 5-12-17 FinalDocumento86 páginasSad Report 5-12-17 FinalRaeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 1Documento11 páginasChapter 1Raeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Summary, Conclusions and RecommendationsDocumento3 páginasSummary, Conclusions and RecommendationsRaeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

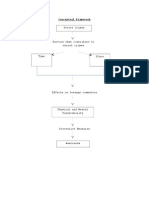

- Conceptual Framework1Documento1 páginaConceptual Framework1Raeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Ifs (Poem)Documento2 páginasIfs (Poem)Raeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Nation (Article Mrec), Pagematch: 1, Sectionmatch: 1Documento1 páginaNation (Article Mrec), Pagematch: 1, Sectionmatch: 1Raeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Project in TLE: Visual Basic: 7 Raeven Davis 9-St. GertrudeDocumento12 páginasProject in TLE: Visual Basic: 7 Raeven Davis 9-St. GertrudeRaeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- BIR Form 1700Documento2 páginasBIR Form 1700Al Ison MangampatAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 23Documento26 páginasChapter 23Raeanne DavisAinda não há avaliações

- Upcat Form 1 Pds2014Documento2 páginasUpcat Form 1 Pds2014mynoytechAinda não há avaliações

- Gameswithoutfrontiers BibliographyDocumento79 páginasGameswithoutfrontiers BibliographyDiogo CarvalhoAinda não há avaliações

- Islam in the Eyes of Non-Muslims: Understanding MisconceptionsDocumento12 páginasIslam in the Eyes of Non-Muslims: Understanding MisconceptionsShan DevAinda não há avaliações

- Malacanang Gov PH 75096 Destruction of IntramurosDocumento15 páginasMalacanang Gov PH 75096 Destruction of IntramurosviancaAinda não há avaliações

- Skin For Skin by Gerald M. SiderDocumento44 páginasSkin For Skin by Gerald M. SiderDuke University Press100% (1)

- American Civil War BookletDocumento5 páginasAmerican Civil War BookletEsih WinangsihAinda não há avaliações

- CDocumento14 páginasCVăn Dương NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Battle of Pusan PerimeterDocumento24 páginasBattle of Pusan PerimeterbangjgAinda não há avaliações

- The Character of War in The 21st Century Paradoxes... - (2 Insurgency and Terrorism Is There A Difference)Documento15 páginasThe Character of War in The 21st Century Paradoxes... - (2 Insurgency and Terrorism Is There A Difference)Jack McCartneyAinda não há avaliações

- Neil Thomas - Medieval: Play Sequence Charges MovementDocumento1 páginaNeil Thomas - Medieval: Play Sequence Charges Movementdkleeman4444Ainda não há avaliações

- Hybrid Warfare in History: Peter R. MansoorDocumento10 páginasHybrid Warfare in History: Peter R. MansoorWaleed Bin Mosam KhattakAinda não há avaliações

- What Is Peacekeeping 2003Documento10 páginasWhat Is Peacekeeping 2003Bilal KhiljiAinda não há avaliações

- FIORI, José Luis. The Global Power, Its Expansion and Its LimitsDocumento68 páginasFIORI, José Luis. The Global Power, Its Expansion and Its LimitsRenato SaraivaAinda não há avaliações

- Position PaperDocumento1 páginaPosition Paperapi-255399044Ainda não há avaliações

- Cyberpunk Timeline: 1990s Events and TrendsDocumento28 páginasCyberpunk Timeline: 1990s Events and TrendsFabricio MoreiraAinda não há avaliações

- Lions Led by Donkeys WWI AssessmentDocumento2 páginasLions Led by Donkeys WWI AssessmentRyka RameshAinda não há avaliações

- 1704usstrike PDFDocumento4 páginas1704usstrike PDFDins PutrajayaAinda não há avaliações

- Religious Extremism in Pakistan: Causes and ConsequencesDocumento14 páginasReligious Extremism in Pakistan: Causes and ConsequencesMaha AliAinda não há avaliações

- Final Draft Comparative Rhetoric AnalysisDocumento5 páginasFinal Draft Comparative Rhetoric Analysisapi-608437776Ainda não há avaliações

- Command and Control (C2)Documento9 páginasCommand and Control (C2)Philip GommesenAinda não há avaliações

- UN Committee Tackles Global Disarmament ChallengesDocumento36 páginasUN Committee Tackles Global Disarmament ChallengesHaseebEjazAinda não há avaliações

- Lieber Code LessonDocumento8 páginasLieber Code LessonJames LittleAinda não há avaliações

- Conscientious ObjectorDocumento5 páginasConscientious ObjectorAlezender TanAinda não há avaliações