Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleedin1

Enviado por

Hendy SetiawanDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleedin1

Enviado por

Hendy SetiawanDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Author: Amir Estephan, MD; Chief Editor: Pamela L Dyne, MD more...

Background

Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common presenting problem in the ED. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) is defined as abnormal uterine bleeding in the absence of organic disease. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is the most common cause of abnormal vaginal bleeding during a woman's reproductive years. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding can have a substantial financial and quality-of-life burden.[1] It affects women's health both medically and socially.

Pathophysiology

The normal menstrual cycle is 28 days and starts on the first day of menses. During the first 14 days (follicular phase) of the menstrual cycle, the endometrium thickens under the influence of estrogen. In response to rising estrogen levels, the pituitary gland secretes follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which stimulate the release of an ovum at the midpoint of the cycle. The residual follicular capsule forms the corpus luteum. After ovulation, the luteal phase begins and is characterized by production of progesterone from the corpus luteum. Progesterone matures the lining of the uterus and makes it more receptive to implantation. If implantation does not occur, in the absence of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), the corpus luteum dies, accompanied by sharp drops in progesterone and estrogen levels. Hormone withdrawal causes vasoconstriction in the spiral arterioles of the endometrium. This leads to menses, which occurs approximately 14 days after ovulation when the ischemic endometrial lining becomes necrotic and sloughs.[2] Terms frequently used to describe abnormal uterine bleeding:

Menorrhagia - Prolonged (>7 d) or excessive (>80 mL daily) uterine bleeding occurring at regular intervals Metrorrhagia - Uterine bleeding occurring at irregular and more frequent than normal intervals Menometrorrhagia - Prolonged or excessive uterine bleeding occurring at irregular and more frequent than normal intervals Intermenstrual bleeding - Uterine bleeding of variable amounts occurring between regular menstrual periods Midcycle spotting - Spotting occurring just before ovulation, typically from declining estrogen levels Postmenopausal bleeding - Recurrence of bleeding in a menopausal woman at least 6 months to 1 year after cessation of cycles Amenorrhea - No uterine bleeding for 6 months or longer

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a diagnosis of exclusion. It is ovulatory or anovulatory bleeding, diagnosed after pregnancy, medications, iatrogenic causes, genital tract pathology, malignancy, and systemic disease have been ruled out by appropriate investigations.

Approximately 90% of dysfunctional uterine bleeding cases result from anovulation, and 10% of cases occur with ovulatory cycles.[3] Anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding results from a disturbance of the normal hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and is particularly common at the extremes of the reproductive years. When ovulation does not occur, no progesterone is produced to stabilize the endometrium; thus, proliferative endometrium persists. Bleeding episodes become irregular, and amenorrhea, metrorrhagia, and menometrorrhagia are common. Bleeding from anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding is thought to result from changes in prostaglandin concentration, increased endometrial responsiveness to vasodilating prostaglandins, and changes in endometrial vascular structure. In ovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding, bleeding occurs cyclically, and menorrhagia is thought to originate from defects in the control mechanisms of menstruation. It is thought that, in women with ovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding, there is an increased rate of blood loss resulting from vasodilatation of the vessels supplying the endometrium due to decreased vascular tone, and prostaglandins have been strongly implicated. Therefore, these women lose blood at rates about 3 times faster than women with normal menses.[4]

Epidemiology

Frequency United States

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is one of the most often encountered gynecologic problems. An estimated 5% of women aged 30-49 years will consult a physician each year for the treatment of menorrhagia. About 30% of all women report having had menorrhagia.[4]

International

No cultural predilection is present with this disease state.

Mortality/Morbidity

Morbidity is related to the amount of blood loss at the time of menstruation, which occasionally is severe enough to cause hemorrhagic shock. Excessive menstrual bleeding accounts for two thirds of all hysterectomies and most endoscopic endometrial destructive surgery. Menorrhagia has several adverse effects, including anemia and iron deficiency, reduced quality of life, and increased healthcare costs.[1]

Race

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding has no predilection for race; however, black women have a higher incidence of leiomyomas and, as a result, they are prone to experiencing more episodes of abnormal vaginal bleeding.

Age

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is most common at the extreme ages of a woman's reproductive years, either at the beginning or near the end, but it may occur at any time during her reproductive life.

Most cases of dysfunctional uterine bleeding in adolescent girls occur during the first 2 years after the onset of menstruation, when their immature hypothalamic-pituitary axis may fail to respond to estrogen and progesterone, resulting in anovulation. Abnormal uterine bleeding affects up to 50% of perimenopausal women. In the perimenopausal period, dysfunctional uterine bleeding may be an early manifestation of ovarian failure causing decreased hormone levels or responsiveness to hormones, thus also leading to anovulatory cycles. In patients who are 40 years or older, the number and quality of ovarian follicles diminishes. Follicles continue to develop but do not produce enough estrogen in response to FSH to trigger ovulation. The estrogen that is produced usually results in late-cycle estrogen breakthrough bleeding.[2]

History

Patients often present with complaints of amenorrhea, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, or menometrorrhagia. The amount and frequency of bleeding and the duration of symptoms, as well as the relationship to the menstrual cycle, should be established. Ask patients to compare the number of pads or tampons used per day in a normal menstrual cycle to the number used at the time of presentation. The average tampon or pad absorbs 20-30 mL or vaginal effluent. Personal habits vary greatly among women; therefore, the number of pads or tampons used is unreliable. The patient should be questioned about the possibility of pregnancy.[3] A reproductive history should always be obtained, including the following: o Age of menarche and menstrual history and regularity o Last menstrual period (LMP), including flow, duration, and presence of dysmenorrhea o Postcoital bleeding o Gravida and para o Previous abortion or recent termination of pregnancy o Contraceptive use, use of barrier protection, and sexual activity (including vigorous sexual activity or trauma) o History of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) or ectopic pregnancy Questions about medical history should include the following: o Signs and symptoms of anemia or hypovolemia (including fatigue, dizziness, and syncope) o Diabetes mellitus o Thyroid disease o Endocrine problems or pituitary tumors o Liver disease o Recent illness, psychological stress, excessive exercise, or weight change

Medication usage, including exogenous hormones, anticoagulants, aspirin, anticonvulsants, and antibiotics o Alternative and complementary medicine modalities, such as herbs and supplements An international expert panel including obstetrician/gynecologists and hematologists has issued guidelines to assist physicians to better recognize bleeding disorders, such as von Willebrand disease, as a cause of menorrhagia and postpartum hemorrhage and to provide diseasespecific therapy for the bleeding disorder.[5] Historically, a lack of awareness of underlying bleeding disorders has led to underdiagnosis in women with abnormal reproductive tract bleeding. The panel provided expert consensus recommendations on how to identify, confirm, and manage a bleeding disorder. If a bleeding disorder is suspected, evaluation for a coagulation problem is required and consultation with a hematologist is suggested. An underlying bleeding disorder should be considered when a patient has any of the following: o Menorrhagia since menarche o Family history of bleeding disorders o Personal history of 1 or several of the following: Notable bruising without known injury Bleeding of oral cavity or GI tract without obvious lesion Epistaxis >10 min duration (possibly necessitating packing or cautery)

o

Physical

Vital signs, including postural changes, should be assessed. Initial evaluation should be directed at assessing the patient's volume status and degree of anemia. Examine for pallor and absence of conjunctival vessels to gauge anemia. An abdominal examination should be performed. Femoral and inguinal lymph nodes should be examined. Stool should be evaluated for the presence of blood. Patients who are hemodynamically stable require a pelvic speculum, bimanual, and rectovaginal examination to define the etiology of vaginal bleeding. A careful physical examination will exclude vaginal or rectal sources of bleeding. The examination should look for the following: o The vagina should be inspected for signs of trauma, lesions, infection, and foreign bodies. o The cervix should be visualized and inspected for lesions, polyps, infection, or intrauterine device (IUD). o Bleeding from the cervical os o A rectovaginal examination should be performed to evaluate the cul-de-sac, posterior wall of the uterus, and uterosacral ligaments. Uterine or ovarian structural abnormalities, including leiomyoma or fibroid uterus, may be noted on bimanual examination. Patients with hematologic pathology may also have cutaneous evidence of bleeding diathesis. Physical findings include petechiae, purpura, and mucosal bleeding (eg, gums) in addition to vaginal bleeding. Patients with liver disease that has resulted in a coagulopathy may manifest additional symptomatology because of abnormal hepatic function. Evaluate patients for spider angioma, palmar erythema, splenomegaly, ascites, jaundice, and asterixis.

Women with polycystic ovary disease present with signs of hyperandrogenism, including hirsutism, obesity, acne, palpable enlarged ovaries, and acanthosis nigricans (hyperpigmentation typically seen in the folds of the skin in the neck, groin, or axilla) Hyperactive and hypoactive thyroid can cause menstrual irregularities. Patients may have varying degrees of characteristic vital sign abnormalities, eye findings, tremors, changes in skin texture, and weight change. Goiter may be present.

Causes

Systemic disease, including thrombocytopenia, hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, Cushing disease, liver disease, diabetes mellitus, and adrenal and other endocrine disorders, can present as abnormal uterine bleeding. Pregnancy and pregnancy-related conditions may be associated with vaginal bleeding. Trauma to the cervix, vulva, or vagina may cause abnormal bleeding. Carcinomas of the vagina, cervix, uterus, and ovaries must always be considered in patients with the appropriate history and physical examination findings. Endometrial cancer is associated with obesity, diabetes mellitus, anovulatory cycles, nulliparity, and age older than 35 years. Other causes of abnormal uterine bleeding include structural disorders, such as functional ovarian cysts, cervicitis, endometritis, salpingitis, leiomyomas, and adenomyosis. Cervical dysplasia or other genital tract pathology may present as postcoital or irregular bleeding. Polycystic ovary disease results in excess estrogen production and commonly presents as abnormal uterine bleeding. Primary coagulation disorders, such as von Willebrand disease, myeloproliferative disorders, and immune thrombocytopenia, can present with menorrhagia. Excessive exercise, stress, and weight loss cause hypothalamic suppression leading to abnormal uterine bleeding due to disruption along the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovarian pathway. Bleeding disturbances are common with combination oral contraceptive pills as well as progestin-only methods of birth control. However, the incidence of bleeding decreases significantly with time. Therefore, only counseling and reassurance are required during the early months of use. Contraceptive intrauterine devices (IUDs) can cause variable vaginal bleeding for the first few cycles after placement and intermittent spotting subsequently. The progesterone impregnated IUD (Mirena) is associated with less menometrorrhagia and usually results in secondary amenorrhea.

[2]

Differentials

Abortion, Complete Abortion, Incomplete Abortion, Inevitable Abortion, Missed Abortion, Threatened Abruptio Placentae

Adenomyosis Anovulation Anticoagulants Antipsychotics Arteriovenous Malformations Cervical Cancer Cervicitis Coagulopathies Cushing Syndrome Endocervical Polyp Endometrial Carcinoma Endometrial Polyp Endometriosis Estrogen Therapy Fibroids (leiomyomata) Foreign body Hydatidiform Mole Hyperthyroidism Hypothyroidism Intrauterine devices Liver disease Mullerian Duct Anomalies Oral contraceptives Ovarian Cysts Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Placenta Previa Platelet Disorders Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome Pregnancy, Ectopic Prolactinoma Renal disease Trauma von Willebrand Disease Vulvovaginitis

Laboratory Studies

When evaluating a woman of reproductive age with vaginal bleeding, pregnancy must always be ruled out by urine or serum human chorionic gonadotropin. In a patient with any hemodynamic instability, excessive bleeding, or clinical evidence of anemia, a complete blood count is essential. Coagulation studies should be considered when indicated by the history or physical examination findings and in patients with underlying liver disease or other coagulopathies. In patients with suspected endocrine disorders, other laboratory studies such as thyroid function tests and prolactin levels may be helpful, although these results may not be available from the ED.

Imaging Studies

Pelvic ultrasonography is an important imaging modality for nonpregnant patients with abnormal vaginal bleeding. It may determine the etiology of

the bleeding such as a fibroid uterus, endometrial thickening, or a focal mass. o Thickened endometrium may indicate an underlying lesion or excess estrogen and may be suggestive of malignancy. An endometrial stripe measuring less than 4 mm thick is unlikely to have endometrial hyperplasia or cancer, and biopsy is often considered unnecessary before treatment. Women with a normal endometrial stripe (512 mm) may require biopsy, particularly if they have risk factors for endometrial cancer. When the endometrial stripe is larger than 12 mm, a biopsy should be performed.[6] o Depending on the urgency to determine the etiology of bleeding and on the reliability of outpatient follow-up, ultrasonography may be deferred for outpatient evaluations because for the majority of nonpregnant patients, ultrasonographic findings do not immediately affect ED decision-making.[3] Transvaginal ultrasonography may be particularly helpful in further delineating ovarian cysts and fluid in the cul-de-sac. Computed tomography is used primarily for evaluation of other causes of acute abdominal or pelvic pain. Magnetic resonance imaging is used primarily for cancer staging.

Procedures

Before instituting therapy, many consulting gynecologists perform endometrial sampling or biopsy to diagnose intrauterine pathology and to exclude endometrial malignancy. Endometrial biopsy is indicated for the following patients with abnormal uterine bleeding[6] : o Women older than 35 years o Obese patients o Women who have prolonged periods of unopposed estrogen stimulation o Women with chronic anovulation Hysteroscopy is the definitive way to detect intrauterine lesions. It offers a more complete examination of the surface of the endometrium. However, it is usually reserved for treating lesions that were detected by other less invasive means.

Emergency Department Care

Hemodynamically unstable patients with uncontrolled bleeding and signs of significant blood loss should have aggressive resuscitation with saline and blood as with other types of hemorrhagic shock. o Evaluate ABCs and address the priorities. o Initiate 2 large-bore intravenous lines (IVs), oxygen, and cardiac monitor. o If bleeding is profuse and the patient is unresponsive to initial fluid management, consider administration of IV conjugated estrogen (Premarin) 25 mg IV every 4-6 hours until the bleeding stops. o In women with severe, persistent uterine bleeding, an immediate dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure may be necessary.

Combination oral contraceptive pills may be used in women who are not pregnant and have no anatomic abnormalities. An oral contraceptive with 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol can be taken twice a day until the bleeding stops for up to 7 days, at which time the dose is decreased to once a day until the pack is completed. They provide the additional benefits of reducing dysmenorrhea and providing contraception. Side effects include nausea and vomiting.[3] Progesterone alone can be used to stabilize an immature endometrium. It is usually successful in the treatment of women with anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) because these women have unopposed estrogen stimulation. Medroxyprogesterone acetate 10 mg is taken orally once daily for 10 days, followed by withdrawal bleeding 3-5 days after completion of the course. Currently, there is not enough evidence comparing the effect of either progesterone alone or in combination with estrogens for the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding.[7] Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are generally effective for the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding and dysmenorrhea. NSAIDs inhibit cyclooxygenase in the arachidonic acid cascade, thus inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis and increasing thromboxane A2 levels. This leads to vasoconstriction and increased platelet aggregation. These medications may reduce blood loss by 20-50%. NSAIDs are most effective if used with the onset of menses or just prior to its onset and continued throughout its duration. Danazol creates a hypoestrogenic and hyperandrogenic environment, which induces endometrial atrophy resulting in reduced menstrual loss. Side effects include musculoskeletal pain, breast atrophy, hirsutism, weight gain, oily skin, and acne. Because of the significant androgenic side effects, this drug is usually reserved as a second-line treatment for shortterm use prior to surgery. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists may be helpful for short-term use in inducing amenorrhea and allowing women to rebuild their red blood cell mass. They produce a profound hypoestrogenic state similar to menopause. Side effects include menopausal symptoms and bone loss with long-term use. Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic drug that exerts its effects by reversibly inhibiting plasminogen. It diminishes fibrinolytic activity within endometrial vessels to prevent bleeding. It has been shown effective in reducing bleeding in up to half of women with dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Tranexamic acid is not approved for the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding in the United States.[6]

Consultations

Seek an emergency gynecologic consultation for patients requiring hemodynamic stabilization. If parenteral therapy does not completely arrest vaginal bleeding in the hemodynamically unstable patient, an emergency D&C may be warranted. Consultation with or urgent referral to a gynecologist for surgical treatment may be necessary for patients who do not desire fertility and in whom medical therapy fails. Both endometrial ablation and hysterectomy are effective treatments in women with dysfunctional uterine bleeding with comparable patient satisfaction rates.[8]

Endometrial ablation may be performed using laser, electrocautery, or rollerball. Amenorrhea is seen in approximately 35% of women treated, and decreased flow is seen in another 45%; although, treatment failures increase with time following the procedure due to endometrial regeneration. A substantial number of patients receiving endometrial ablation require reoperation (30% by 48 months). Hysterectomy is the most effective treatment for bleeding. However, it is associated with more frequent and severe adverse events compared with either conservative medical or ablation procedures. Operating time, hospitalization, recovery times, and costs are also greater. Hence, hysterectomy is reserved for selected patient populations.

Summary

The management of postterm pregnancies is complicated and fraught with complex issues. The decision of whether to induce labor or to proceed with expectant management with or without antepartum fetal surveillance is not taken lightly. Data support inducing labor at 41 weeks' gestation in an accurately dated, low-risk pregnancy, regardless of cervical examination findings. This strategy, although not without its critics, averts the need for antepartum fetal surveillance and does not increase the cesarean delivery rate; in fact, it may decrease the cesarean delivery rate. References

1. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetricians-

2. 3. 4.

5.

6.

7. 8. 9.

gynecologists. Number 55, September 2004 (replaces practice pattern number 6, October 1997). Management of Postterm Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2004;104(3):639-46. [Medline]. Norwitz ER, Snegovskikh VV, Caughey AB. Prolonged pregnancy: when should we intervene?. Clin Obstet Gynecol. Jun 2007;50(2):547-57. [Medline]. Taipale P, Hiilesmaa V. Predicting delivery date by ultrasound and last menstrual period in early gestation. Obstet Gynecol. Feb 2001;97(2):189-94. [Medline]. Savitz DA, Terry JW Jr, Dole N, et al. Comparison of pregnancy dating by last menstrual period, ultrasound scanning, and their combination. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Dec 2002;187(6):1660-6. [Medline]. Bennett KA, Crane JM, O'shea P, et al. First trimester ultrasound screening is effective in reducing postterm labor induction rates: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Apr 2004;190(4):1077-81. [Medline]. Caughey AB, Nicholson JM, Washington AE. First versus Second Trimester Ultrasound: The Effect on Pregnancy Dating and Perinatal Outcomes. In Press, Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;[Medline]. Mogren I, Stenlund H, Hogberg U. Recurrence of prolonged pregnancy. Int J Epidemiol. Apr 1999;28(2):253-7. [Medline]. Olesen AW, Basso O, Olsen J. An estimate of the tendency to repeat postterm delivery. Epidemiology. Jul 1999;10(4):468-9. [Medline]. Divon MY, Ferber A, Nisell H, et al. Male gender predisposes to prolongation of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2002;187(4):1081-3. [Medline].

10. Laursen M, Bille C, Olesen AW, et al. Genetic influence on prolonged gestation: a

population-based Danish twin study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Feb 2004;190(2):489-94. [Medline]. 11. Hickey CA, Cliver SP, McNeal SF, et al. Low pregravid body mass index as a risk factor for preterm birth: variation by ethnic group. Obstet Gynecol. Feb 1997;89(2):206-12. [Medline]. 12. Usha Kiran TS, Hemmadi S, Bethel J, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in a woman with an increased body mass index. BJOG. Jun 2005;112(6):768-72. [Medline]. 13. Stotland NE, Washington AE, Caughey AB. Prepregnancy body mass index and the length of gestation at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2007;197(4):378.e1-5. [Medline]. 14. Yudkin PL, Wood L, Redman CW. Risk of unexplained stillbirth at different gestational ages. Lancet. May 23 1987;1(8543):1192-4. [Medline]. 15. Feldman GB. Prospective risk of stillbirth. Obstet Gynecol. Apr 1992;79(4):547-53. [Medline]. 16. Hilder L, Costeloe K, Thilaganathan B. Prolonged pregnancy: evaluating gestationspecific risks of fetal and infant mortality. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. Feb 1998;105(2):169-73. [Medline]. 17. Cotzias CS, Paterson-Brown S, Fisk NM. Prospective risk of unexplained stillbirth in singleton pregnancies at term: population based analysis. BMJ. Jul 31 1999;319(7205):287-8. [Medline]. 18. Rand L, Robinson JN, Economy KE, et al. Post-term induction of labor revisited. Obstet Gynecol. Nov 2000;96(5 Pt 1):779-83. [Medline]. 19. Smith GC. Life-table analysis of the risk of perinatal death at term and post term in singleton pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Feb 2001;184(3):489-96. [Medline]. 20. Froen JF, Arnestad M, Frey K, et al. Risk factors for sudden intrauterine unexplained death: epidemiologic characteristics of singleton cases in Oslo, Norway, 1986-1995. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Mar 2001;184(4):694-702. [Medline]. 21. Yoder BA, Kirsch EA, Barth WH, et al. Changing obstetric practices associated with decreasing incidence of meconium aspiration syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. May 2002;99(5 Pt 1):731-9. [Medline]. 22. Caughey AB, Washington AE, Laros RK Jr. Neonatal complications of term pregnancy: rates by gestational age increase in a continuous, not threshold, fashion. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Jan 2005;192(1):185-90. [Medline]. 23. Caughey AB, Musci TJ. Complications of term pregnancies beyond 37 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. Jan 2004;103(1):57-62. [Medline]. 24. Heimstad R, Romundstad PR, Salvesen KA. Induction of labour for post-term pregnancy and risk estimates for intrauterine and perinatal death. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(2):247-9. [Medline]. 25. Herabutya Y, Prasertsawat PO, Tongyai T, Isarangura Na Ayudthya N. Prolonged pregnancy: the management dilemma. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. Apr 1992;37(4):253-8. [Medline]. 26. Kahn B, Lumey LH, Zybert PA, Lorenz JM, Cleary-Goldman J, D'Alton ME, et al. Prospective risk of fetal death in singleton, twin, and triplet gestations: implications for practice. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2003;102(4):685-92. [Medline]. 27. Campbell MK, Ostbye T, Irgens LM. Post-term birth: risk factors and outcomes in a 10-year cohort of Norwegian births. Obstet Gynecol. Apr 1997;89(4):543-8. [Medline]. 28. Alexander JM, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Forty weeks and beyond: pregnancy outcomes by week of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. Aug 2000;96(2):291-4. [Medline].

29. Treger M, Hallak M, Silberstein T, et al. Post-term pregnancy: should induction of

labor be considered before 42 weeks?. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. Jan 2002;11(1):50-3. [Medline]. 30. Caughey AB, Stotland NE, Washington AE, et al. Maternal and obstetric complications of pregnancy are associated with increasing gestational age at term. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Feb 2007;196(2):155.e1-6. [Medline]. 31. Heimstad R, Romundstad PR, Eik-Nes SH, et al. Outcomes of pregnancy beyond 37 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2006;108(3 Pt 1):500-8. [Medline]. 32. Caughey AB, Nicholson JM, Cheng YW, et al. Induction of labor and cesarean delivery by gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Sep 2006;195(3):700-5. [Medline]. 33. Caughey AB, Stotland NE, Escobar GJ. What is the best measure of maternal complications of term pregnancy: ongoing pregnancies or pregnancies delivered?. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2003;189(4):1047-52. [Medline]. 34. Hannah ME. Postterm pregnancy: should all women have labour induced? A review of the literature. Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review. 1993;5:3. 35. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Fetal Macrosomia. ACOG Practice Bulletin #22. ACOG. Washington, DC: 2000. 36. Spellacy WN, Miller S, Winegar A, et al. Macrosomia--maternal characteristics and infant complications. Obstet Gynecol. Aug 1985;66(2):158-61. [Medline]. 37. Rosen MG, Dickinson JC. Management of post-term pregnancy. N Engl J Med. Jun 11 1992;326(24):1628-9. [Medline]. 38. Shime J, Librach CL, Gare DJ, et al. The influence of prolonged pregnancy on infant development at one and two years of age: a prospective controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Feb 1986;154(2):341-5. [Medline]. 39. Kabbur PM, Herson VC, Zaremba S, et al. Have the year 2000 neonatal resuscitation program guidelines changed the delivery room management or outcome of meconium-stained infants?. J Perinatol. Nov 2005;25(11):694-7. [Medline]. 40. Hofmeyr GJ. Amnioinfusion for meconium-stained liquor in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;CD000014. [Medline]. 41. [Best Evidence] Fraser WD, Hofmeyr J, Lede R, Faron G, Alexander S, Goffinet F, et al. Amnioinfusion for the prevention of the meconium aspiration syndrome. N Engl J Med. Sep 1 2005;353(9):909-17. [Medline]. 42. Vain NE, Szyld EG, Prudent LM, et al. Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal suctioning of meconium-stained neonates before delivery of their shoulders: multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Aug 14-20 2004;364(9434):597-602. [Medline]. 43. Badawi N, Kurinczuk JJ, Keogh JM, Alessandri LM, O'Sullivan F, Burton PR, et al. Antepartum risk factors for newborn encephalopathy: the Western Australian casecontrol study. BMJ. Dec 5 1998;317(7172):1549-53. [Medline]. 44. [Best Evidence] Bruckner TA, Cheng YW, Caughey AB. Increased neonatal mortality among normal-weight births beyond 41 weeks of gestation in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Jul 16 2008;[Medline]. 45. Nicholson JM, Kellar LC, Kellar GM. The impact of the interaction between increasing gestational age and obstetrical risk on birth outcomes: evidence of a varying optimal time of delivery. J Perinatol. Jul 2006;26(7):392-402. [Medline]. 46. Moster D, Wilcox AJ, Vollset SE, Markestad T, Lie RT. Cerebral palsy among term and postterm births. JAMA. Sep 1 2010;304(9):976-82. [Medline]. 47. Eden RD, Seifert LS, Winegar A, et al. Perinatal characteristics of uncomplicated postdate pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. Mar 1987;69(3 Pt 1):296-9. [Medline].

48. Heimstad R, Romundstad PR, Hyett J, et al. Women's experiences and attitudes

towards expectant management and induction of labor for post-term pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2007;86(8):950-6. [Medline]. 49. Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hellmann J, Hewson S, Milner R, Willan A. Induction of labor as compared with serial antenatal monitoring in post-term pregnancy. A randomized controlled trial. The Canadian Multicenter Post-term Pregnancy Trial Group. N Engl J Med. Jun 11 1992;326(24):1587-92. [Medline]. 50. NICHD. A clinical trial of induction of labor versus expectant management in postterm pregnancy. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Mar 1994;170(3):716-23. [Medline]. 51. Knox GE, Huddleston JF, Flowers CE Jr. Management of prolonged pregnancy: results of a prospective randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Jun 15 1979;134(4):376-84. [Medline]. 52. [Best Evidence] Glmezoglu AM, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Oct 18 2006;CD004945. [Medline]. 53. Sanchez-Ramos L, Olivier F, Delke I, et al. Labor induction versus expectant management for postterm pregnancies: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. Jun 2003;101(6):1312-8. [Medline]. 54. Kaimal AJ, Little SE, Odibo AO, Stamilio DM, Grobman WA, Long EF, et al. Costeffectiveness of elective induction of labor at 41 weeks in nulliparous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Feb 2011;204(2):137.e1-9. [Medline]. 55. Caughey AB, Bishop JT. Maternal complications of pregnancy increase beyond 40 weeks of gestation in low-risk women. J Perinatol. Sep 2006;26(9):540-5. [Medline]. 56. Menticoglou SM, Hall PF. Routine induction of labour at 41 weeks gestation: nonsensus consensus. BJOG. May 2002;109(5):485-91. [Medline]. 57. [Best Evidence] de Miranda E, van der Bom JG, Bonsel GJ, et al. Membrane sweeping and prevention of post-term pregnancy in low-risk pregnancies: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. Apr 2006;113(4):402-8. [Medline]. 58. Boulvain M, Stan C, Irion O. Membrane sweeping for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jan 25 2005;CD000451. [Medline]. 59. Kashanian M, Akbarian A, Baradaran H, et al. Effect of membrane sweeping at term pregnancy on duration of pregnancy and labor induction: a randomized trial. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;62(1):41-4. [Medline]. 60. Tan PC, Andi A, Azmi N, et al. Effect of coitus at term on length of gestation, induction of labor, and mode of delivery. Obstet Gynecol. Jul 2006;108(1):134-40. [Medline]. 61. Schaffir J. Sexual intercourse at term and onset of labor. Obstet Gynecol. Jun 2006;107(6):1310-4. [Medline]. 62. Kavanagh J, Kelly AJ, Thomas J. Sexual intercourse for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;CD003093. [Medline]. 63. [Best Evidence] Tan PC, Yow CM, Omar SZ. Effect of coital activity on onset of labor in women scheduled for labor induction: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2007;110(4):820-6. [Medline]. 64. Rabl M, Ahner R, Bitschnau M, et al. Acupuncture for cervical ripening and induction of labor at term--a randomized controlled trial. Wien Klin Wochenschr. Dec 17 2001;113(23-24):942-6. [Medline]. 65. Smith CA, Crowther CA. Acupuncture for induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD002962. [Medline].

66. Rozenberg P, Chevret S, Senat MV, et al. A randomized trial that compared

intravaginal misoprostol and dinoprostone vaginal insert in pregnancies at high risk of fetal distress. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Jul 2004;191(1):247-53. [Medline]. 67. Bochner CJ, Medearis AL, Davis J, et al. Antepartum predictors of fetal distress in postterm pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Aug 1987;157(2):353-8. [Medline]. 68. Hashimoto B, Filly RA, Belden C, et al. Objective method of diagnosing oligohydramnios in postterm pregnancies. J Ultrasound Med. Feb 1987;6(2):81-4. [Medline]. 69. Morris JM, Thompson K, Smithey J, et al. The usefulness of ultrasound assessment of amniotic fluid in predicting adverse outcome in prolonged pregnancy: a prospective blinded observational study. BJOG. Nov 2003;110(11):989-94. [Medline]. 70. Alfirevic Z, Walkinshaw SA. Management of post-term pregnancy: to induce or not?. Br J Hosp Med. Sep 7-20 1994;52(5):218-21. [Medline]. 71. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Antepartum fetal surveillance. ACOG Practice Bulletin #9. ACOG. Washington, DC: 1999. 72. Bochner CJ, Williams J 3rd, Castro L, et al. The efficacy of starting postterm antenatal testing at 41 weeks as compared with 42 weeks of gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Sep 1988;159(3):550-4. [Medline]. 73. Clement D, Schifrin BS, Kates RB. Acute oligohydramnios in postdate pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Oct 1987;157(4 Pt 1):884-6. [Medline]. 74. Cotzias CS, Paterson-Brown S, Fisk NM. Prospective risk of unexplained stillbirth in singleton pregnancies at term: population based analysis. BMJ. Jul 31 1999;319(7205):287-8. [Medline]. 75. Crowley P. Interventions for preventing or improving the outcome of delivery at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;CD000170. [Medline]. 76. Crowley P, O'Herlihy C, Boylan P. The value of ultrasound measurement of amniotic fluid volume in the management of prolonged pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. May 1984;91(5):444-8. [Medline]. 77. Foong LC, Vanaja K, Tan G, et al. Membrane sweeping in conjunction with labor induction. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2000;96(4):539-42. [Medline]. 78. Gardosi J, Vanner T, Francis A. Gestational age and induction of labour for prolonged pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. Jul 1997;104(7):792-7. [Medline]. 79. Grant JM. Induction of labour confers benefits in prolonged pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. Feb 1994;101(2):99-102. [Medline]. 80. Guinn DA, Goepfert AR, Christine M, et al. Extra-amniotic saline, laminaria, or prostaglandin E(2) gel for labor induction with unfavorable cervix: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. Jul 2000;96(1):106-12. [Medline]. 81. Harman JH Jr, Kim A. Current trends in cervical ripening and labor induction. Am Fam Physician. Aug 1999;60(2):477-84. [Medline]. 82. Laursen M, Bille C, Olesen AW, et al. Genetic influence on prolonged gestation: a population-based Danish twin study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Feb 2004;190(2):489-94. [Medline]. 83. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. Births: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. Dec 5 2007;56(6):1-103. [Medline]. 84. Naeye RL. Causes of perinatal mortality excess in prolonged gestations. Am J Epidemiol. Nov 1978;108(5):429-33. [Medline]. 85. Neilson JP. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;CD000182. [Medline]. 86. Neilson JP. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;CD000182. [Medline].

87. Nicholson JM, Kellar LC, Cronholm PF, et al. Active management of risk in

pregnancy at term in an urban population: an association between a higher induction of labor rate and a lower cesarean delivery rate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Nov 2004;191(5):1516-28. [Medline]. 88. Nicholson JM, Parry S, Caughey AB, et al. The impact of the active management of risk in pregnancy at term on birth outcomes: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. May 2008;198(5):511.e1-15. [Medline]. 89. Oz AU, Holub B, Mendilcioglu I, et al. Renal artery Doppler investigation of the etiology of oligohydramnios in postterm pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2002;100(4):715-8. [Medline]. 90. Rozenberg P, Chevret S, Ville Y. [Comparison of pre-induction ultrasonographic cervical length and Bishop score in predicting risk of cesarean section after labor induction with prostaglandins]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. Jan-Feb 2005;33(1-2):17-22. [Medline]. 91. Saari-Kemppainen A, Karjalainen O, Ylstalo P, et al. Ultrasound screening and perinatal mortality: controlled trial of systematic one-stage screening in pregnancy. The Helsinki Ultrasound Trial. Lancet. Aug 18 1990;336(8712):387-91. [Medline]. 92. Seyb ST, Berka RJ, Socol ML, et al. Risk of cesarean delivery with elective induction of labor at term in nulliparous women. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 1999;94(4):600-7. [Medline]. 93. Shaw K, Clark SL. Reliability of intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring in the postterm fetus with meconium passage. Obstet Gynecol. Dec 1988;72(6):886-9. [Medline]. 94. Shea KM, Wilcox AJ, Little RE. Postterm delivery: a challenge for epidemiologic research. Epidemiology. Mar 1998;9(2):199-204. [Medline]. 95. Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol. Jun 2006;107(6):1226-32. [Medline]. 96. Stokes HJ, Roberts RV, Newnham JP. Doppler flow velocity waveform analysis in postdate pregnancies. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. Feb 1991;31(1):27-30. [Medline]. 97. Sullivan CA, Benton LW, Roach H, et al. Combining medical and mechanical methods of cervical ripening. Does it increase the likelihood of successful induction of labor?. J Reprod Med. Nov 1996;41(11):823-8. [Medline]. 98. Usha Kiran TS, Hemmadi S, Bethel J, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in a woman with an increased body mass index. BJOG. Jun 2005;112(6):768-72. [Medline]. 99. Vahratian A, Zhang J, Troendle JF, et al. Labor progression and risk of cesarean delivery in electively induced nulliparas. Obstet Gynecol. Apr 2005;105(4):698-704. [Medline]. 100. Ventura SJ, Martin JA, Curtin SC, et al. Births: final data for 1998. Natl Vital Stat Rep. Mar 28 2000;48(3):1-100. [Medline]. 101. Waldenstrom U, Axelsson O, Nilsson S, et al. Effects of routine one-stage ultrasound screening in pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. Sep 10 1988;2(8611):585-8. [Medline]. 102. Xenakis EM, Piper JM, Conway DL, et al. Induction of labor in the nineties: conquering the unfavorable cervix. Obstet Gynecol. Aug 1997;90(2):235-9. [Medline]. 103. Yeast JD, Jones A, Poskin M. Induction of labor and the relationship to cesarean delivery: A review of 7001 consecutive inductions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. Mar 1999;180(3 Pt 1):628-33. [Medline].

104.

Yoder BA, Gordon MC, Barth WH Jr. Late-preterm birth: does the changing obstetric paradigm alter the epidemiology of respiratory complications?. Obstet Gynecol. Apr 2008;111(4):814-22. [Medline].

Você também pode gostar

- The Blood Clotting MechanismDocumento20 páginasThe Blood Clotting Mechanismzynab123Ainda não há avaliações

- Astragalus Root Can Prevent Telomere ShorteningDocumento10 páginasAstragalus Root Can Prevent Telomere Shorteningklumsy15Ainda não há avaliações

- Reproducing Women: Medicine, Metaphor, and Childbirth in Late Imperial ChinaNo EverandReproducing Women: Medicine, Metaphor, and Childbirth in Late Imperial ChinaAinda não há avaliações

- Hydrocele, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo EverandHydrocele, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsAinda não há avaliações

- Manaka HammerDocumento2 páginasManaka Hammerjhonny100% (3)

- Physiology of MenopauseDocumento13 páginasPhysiology of MenopauseChris KoAinda não há avaliações

- 王居易 The Clinical Significance of Palpable Channel Changes PDFDocumento7 páginas王居易 The Clinical Significance of Palpable Channel Changes PDFJose Gregorio ParraAinda não há avaliações

- Menstrual DisordersDocumento29 páginasMenstrual DisordersJesse EstradaAinda não há avaliações

- IVF Acupuncture - DR Guy Gudex DR Vitalis Skiauteris DR Marie BirdsallDocumento1 páginaIVF Acupuncture - DR Guy Gudex DR Vitalis Skiauteris DR Marie Birdsallkiwi_girl_uk100% (1)

- SLE-combined 2 ArshadDocumento71 páginasSLE-combined 2 ArshadarshadsyahaliAinda não há avaliações

- Ectopic Pregnancy ADocumento37 páginasEctopic Pregnancy AJervhen Sky Adolfo Dalisan100% (1)

- Presentation 1Documento20 páginasPresentation 1Mohamad HafyfyAinda não há avaliações

- Case PresentationDocumento36 páginasCase PresentationSaba TariqAinda não há avaliações

- Case Write Up FibroidDocumento17 páginasCase Write Up FibroidNadsri AmirAinda não há avaliações

- Properties of Food From A TCM PerspectiveDocumento5 páginasProperties of Food From A TCM PerspectiveCarl MacCordAinda não há avaliações

- Pregnancy Induced HypertensionDocumento7 páginasPregnancy Induced HypertensionRalph Emerson RatonAinda não há avaliações

- Melancholic - PhlegmaticDocumento5 páginasMelancholic - PhlegmaticSaif Ul HaqAinda não há avaliações

- Case Presentation 1Documento9 páginasCase Presentation 1Sadiasifatafroz SifatAinda não há avaliações

- Case Presentation O&GDocumento76 páginasCase Presentation O&GMalvinder Singh DhillonAinda não há avaliações

- Heat Stroke: Review Open AccessDocumento8 páginasHeat Stroke: Review Open AccessJulian HuningkorAinda não há avaliações

- Dysmenorrhoea: J. Rashma 2015 BATCHDocumento24 páginasDysmenorrhoea: J. Rashma 2015 BATCHRashma JosephAinda não há avaliações

- How To Read A CTGDocumento11 páginasHow To Read A CTGiwennieAinda não há avaliações

- Abnormal Uterine BleedingDocumento36 páginasAbnormal Uterine BleedingPranshu Prajyot 67100% (1)

- Seinlanguage - Jerry SeinfeldDocumento4 páginasSeinlanguage - Jerry Seinfeldxahibehe0% (2)

- Healing Psoriasis by Dr. PaganoDocumento3 páginasHealing Psoriasis by Dr. PaganoXavier GuarchAinda não há avaliações

- Hyperthyroidism With Signs and Symptoms of Thyrotoxicosis: A Case Protocol OnDocumento6 páginasHyperthyroidism With Signs and Symptoms of Thyrotoxicosis: A Case Protocol Onscremo_xtremeAinda não há avaliações

- Multinodular Goitre Case PresentationDocumento19 páginasMultinodular Goitre Case PresentationTamilAinda não há avaliações

- Other Acupuncture Reflection 4Documento13 páginasOther Acupuncture Reflection 4peter911x2134Ainda não há avaliações

- Inflammation & Immune ResponseDocumento68 páginasInflammation & Immune Responsesuday sunday100% (1)

- Seminar 5 - Menopause, HRT, PMBDocumento57 páginasSeminar 5 - Menopause, HRT, PMBAiman ArifinAinda não há avaliações

- Antenatal Care During The First, SecondDocumento85 páginasAntenatal Care During The First, SecondhemihemaAinda não há avaliações

- TCM Obstetrical Assessment and Treatment For Labour PreparationDocumento20 páginasTCM Obstetrical Assessment and Treatment For Labour PreparationCamille EgídioAinda não há avaliações

- LSCS PRESENTATIONDocumento13 páginasLSCS PRESENTATIONMichael AdkinsAinda não há avaliações

- Venous Blood Collection - PresentationDocumento12 páginasVenous Blood Collection - PresentationVickram JainAinda não há avaliações

- Partogram and CTG Reading Skills PDFDocumento52 páginasPartogram and CTG Reading Skills PDFnurul nabillaAinda não há avaliações

- Gestational Diabetes: Dr. Oyeyiola Oyebode Registrar Obstetrics and Gynaecology Ola Catholic Hospital, Oluyoro IbadanDocumento40 páginasGestational Diabetes: Dr. Oyeyiola Oyebode Registrar Obstetrics and Gynaecology Ola Catholic Hospital, Oluyoro Ibadanoyebode oyeyiolaAinda não há avaliações

- Acupresure LI4 BL67Documento10 páginasAcupresure LI4 BL67Dewi Rahmawati Syam100% (1)

- Peripheral Neuropathy TreatmentDocumento3 páginasPeripheral Neuropathy TreatmentSantiago HerreraAinda não há avaliações

- Case PresentationDocumento50 páginasCase Presentationapi-19762967Ainda não há avaliações

- Postpartum Hemorrhage PPHDocumento70 páginasPostpartum Hemorrhage PPHLoungayvan BatuyogAinda não há avaliações

- Constipation: Treatment: Foot Massage: The Massage May Be Applied To Rectum (31), Anus (32), AscendingDocumento0 páginaConstipation: Treatment: Foot Massage: The Massage May Be Applied To Rectum (31), Anus (32), Ascendingrasputin22100% (1)

- Polycystic Kidney DiseaseDocumento15 páginasPolycystic Kidney DiseaseSabita TripathiAinda não há avaliações

- Menstrual DisordersDocumento47 páginasMenstrual DisordersKiranAinda não há avaliações

- Infections of Female Genital TractDocumento67 páginasInfections of Female Genital TractSana AftabAinda não há avaliações

- Vago ThomasDocumento29 páginasVago ThomasEsti Rahmawati SuryaningrumAinda não há avaliações

- Bleeding in Early PregnancyDocumento40 páginasBleeding in Early PregnancyOmar mohamedAinda não há avaliações

- Case History Ob & Gyne 4Documento6 páginasCase History Ob & Gyne 4maksventileAinda não há avaliações

- Acupuncture Point Combinations, The Key To Clinical Success: Doug Eisenstark L.AcDocumento1 páginaAcupuncture Point Combinations, The Key To Clinical Success: Doug Eisenstark L.Aczvika crAinda não há avaliações

- Hypertension Lecture For Cci 2013Documento74 páginasHypertension Lecture For Cci 2013Hannie CruelAinda não há avaliações

- Obstetrics Case PresentationDocumento27 páginasObstetrics Case PresentationMahaprasad sahoo 77Ainda não há avaliações

- Allergic RhinitisDocumento27 páginasAllergic RhinitisArvindhanAinda não há avaliações

- #Comprehensiveclinicalcases #Surgery-Ulcer: Patient ParticularsDocumento5 páginas#Comprehensiveclinicalcases #Surgery-Ulcer: Patient ParticularsRachitha GuttaAinda não há avaliações

- Case Protocol OB - H MOLEDocumento3 páginasCase Protocol OB - H MOLEKim Adarem Joy ManimtimAinda não há avaliações

- History Taking OBS GYNDocumento10 páginasHistory Taking OBS GYNzvkznhsw2tAinda não há avaliações

- OSCE Stop - Lecture Long HistoryDocumento18 páginasOSCE Stop - Lecture Long HistorycrystalsheAinda não há avaliações

- 4 FasesDocumento4 páginas4 FasesFERTIL CONEXIONAinda não há avaliações

- Intrauterine Growth Restriction IUGR: TH THDocumento2 páginasIntrauterine Growth Restriction IUGR: TH THZahra AlaradiAinda não há avaliações

- Vaginitis Case StudyDocumento3 páginasVaginitis Case StudyYunEr Ong50% (2)

- Complementary and Alternative Approach For Pain Management in LabourDocumento9 páginasComplementary and Alternative Approach For Pain Management in LabourPujianti LestarinaAinda não há avaliações

- Faculty of Medicine: DR Archianda Arsad HakimDocumento8 páginasFaculty of Medicine: DR Archianda Arsad HakimnikfarisAinda não há avaliações

- Nurse Writing 016 OET Practice Letter Darryl MahnDocumento3 páginasNurse Writing 016 OET Practice Letter Darryl Mahnchoudharysandeep50163% (8)

- Pharmaceutical SciencesDocumento5 páginasPharmaceutical SciencesiajpsAinda não há avaliações

- Invuity Investor Presentation - Q3 2017Documento22 páginasInvuity Investor Presentation - Q3 2017medtechyAinda não há avaliações

- Ahuja, Motiani - 2004 - Current and Evolving Issues in Transfusion PracticeDocumento8 páginasAhuja, Motiani - 2004 - Current and Evolving Issues in Transfusion Practicesushmakumari009Ainda não há avaliações

- Path Lab Name: Onyedika Egbujo No: #671 Topic: PheochromocytomaDocumento4 páginasPath Lab Name: Onyedika Egbujo No: #671 Topic: PheochromocytomaOnyedika EgbujoAinda não há avaliações

- AmrapDocumento128 páginasAmraphijackerAinda não há avaliações

- Kegawatan Pada Diare Dehidrasi BeratDocumento40 páginasKegawatan Pada Diare Dehidrasi BeratAkram BatjoAinda não há avaliações

- 5z23. ED Crowding Overview and Toolkit (Dec 2015)Documento33 páginas5z23. ED Crowding Overview and Toolkit (Dec 2015)Peter 'Pierre' RobsonAinda não há avaliações

- Infertility HysterosDocumento47 páginasInfertility HysterosDenisAinda não há avaliações

- Draf Resume Askep PpniDocumento4 páginasDraf Resume Askep PpniAbu QisronAinda não há avaliações

- Product English 6Documento16 páginasProduct English 6rpepAinda não há avaliações

- Duchenne Muscular DystrophyDocumento9 páginasDuchenne Muscular Dystrophyapi-306057885Ainda não há avaliações

- Order of Payment: Food and Drug AdministrationDocumento2 páginasOrder of Payment: Food and Drug AdministrationTheGood GuyAinda não há avaliações

- Initial Nurse Patient InteractionDocumento1 páginaInitial Nurse Patient InteractionBryan Jay Carlo PañaAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Abstract FormDocumento1 páginaClinical Abstract FormHihiAinda não há avaliações

- Answer and Rationale Community Health NursingDocumento25 páginasAnswer and Rationale Community Health NursingDENNIS N. MUÑOZ100% (1)

- Title: Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare An Integrated Approach To Healthcare DeliveryDocumento13 páginasTitle: Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare An Integrated Approach To Healthcare DeliveryofhsaosdafsdfAinda não há avaliações

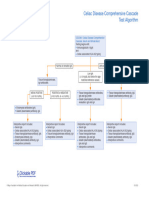

- Celiac Disease Comprehensive Cascade Test AlgorithmDocumento1 páginaCeliac Disease Comprehensive Cascade Test Algorithmayub7walkerAinda não há avaliações

- 1.halliwck Child Principios - Halliwick - en - Nino PDFDocumento7 páginas1.halliwck Child Principios - Halliwick - en - Nino PDFmuhammad yaminAinda não há avaliações

- AKUH Kampala Hospital-Press Release - Final - 17 December 2015Documento3 páginasAKUH Kampala Hospital-Press Release - Final - 17 December 2015Robert OkandaAinda não há avaliações

- Exam 1Documento13 páginasExam 1Ashley NhanAinda não há avaliações

- Read and Choose The Correct Answer From The Box Below.: Boys GirlsDocumento1 páginaRead and Choose The Correct Answer From The Box Below.: Boys GirlsjekjekAinda não há avaliações

- Research ProposalDocumento25 páginasResearch ProposaladerindAinda não há avaliações

- Rose Pharmacy JaipurDocumento6 páginasRose Pharmacy JaipurAmit KochharAinda não há avaliações

- Obsgyn BooksDocumento4 páginasObsgyn BooksYulian NuswantoroAinda não há avaliações

- Unite - October 2013Documento40 páginasUnite - October 2013Bruce SeamanAinda não há avaliações

- Buffer Systems in The Body: Protein Buffers in Blood Plasma and CellsDocumento11 páginasBuffer Systems in The Body: Protein Buffers in Blood Plasma and CellsK Jayakumar KandasamyAinda não há avaliações

- PMLS 2 LEC Module 3Documento8 páginasPMLS 2 LEC Module 3Peach DaquiriAinda não há avaliações

- Article 007Documento6 páginasArticle 007Dyah Putri Ayu DinastyarAinda não há avaliações

- Para JumblesDocumento8 páginasPara Jumblespinisettiswetha100% (1)