Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Jada 2005 Christensen 201 3

Enviado por

Navi GadeDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Jada 2005 Christensen 201 3

Enviado por

Navi GadeDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

OBSERVATIONS GORDON J. CHRISTENSEN, D.D.S., M.S.D., Ph.D.

Longevity of posterior tooth dental restorations

hen you purchase a set of tires, an automobile or a pair of shoes, one of the characteristics you probably consider is the items potential longevity. Manufacturers and retailers often advertise the expected longevity of their products to consumers, and it is not uncommon for the consumer to object when the purchased item wears out or breaks before the expected time. Are estimations of the expected longevity of restorations explained to dental patients? Although the longevity of dental restorations is somewhat predictable, it has been my observation that most dentists do not inform their patients about the expected service period of restorations. Should we be doing so? In my opinion, dental practitioners would generate greater patient satisfaction if they informed patients about the expected longevity of treatment rendered. This concept has been addressed from a legal standpoint and often is referred to as informed consent.1 In this column, I will discuss

the most commonly used dental restorations intended for posterior teeth, candidly appraise the potential service period for these materials and predict their expected modes of failure. I hope that the information will motivate dentists to inform patients about the service potential of dental restorations, thus avoiding future patient confrontations and legal activity.

POSTERIOR TOOTH RESTORATIONS: SERVICE POTENTIAL AND EXPECTED FAILURE MODE

The dental literature and folklore contain highly diverse and confusing predictions regarding longevity of posterior tooth restorations. The following information is based on my own observations from many years of practice, teaching, research, discussion with dentists throughout the world and mentoring many dentists in clinical study clubs. I suggest that the exact number of years that restorations are expected to serve not be expressed to patients, in case the exact predictions are not accurate. I usually explain service potential to patients using one of four categories of

longevity expectations: This restoration should serve (a few years) (several years) (many years) (indefinitely [in the event of an elderly person]). When the treatment includes restoration of many teeth, I suggest that the patient receive a formal completion letter from the practitioner explaining his or her feelings about the expected longevity of the restorations, the necessity for recall appointments and suggested preventive procedures. It is known that all types of restorations for posterior teeth have a variable but finite longevity. When patients know the expected potential service period, redoing the restorations at a later time is not unexpected or upsetting to them. Amalgam. Amalgam still is the most used dental material globally, although a growing percentage of U.S. dentists do not use it. Additionally, some patients will not accept the unsightly appearance of amalgam.2 Nevertheless, I predict that amalgam will continue to compose a significant portion of dental restorations for the immediate future. Amalgam restorations, placed at an average level of quality,

201

JADA, Vol. 136, February 2005 Copyright 2005 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

OBSERVATIONS

serve for many years. Studies on amalgam show widely varied failure and longevity statistics. This variability probably is related to the care with which the restorations were placed, the appropriateness of placing amalgam in the specific tooth preparations, and the oral conditions under which the amalgam was placed. It has been my experience, after placing and observing thousands of amalgam restorations over several decades, that few of them have failed. I predict that a moderately sized mesio-occlusal-distal amalgam restoration, placed by a dentist with average ability, will last for at least 10 years in a typical patient; I have seen some last for 40 years or more. The cost to a patient per year of service for an amalgam restoration is low when compared with that for any other posterior tooth restoration. If failure occurs, it is related to dental caries around margins, fracture of tooth cusps, infrequent fracture of the amalgam itself or darkening of the remaining tooth, which motivates the patient to seek a more esthetically pleasing restoration. Resin-based composite. The first resin-based composite material was introduced as a Class II restorative in 1968. Our own clinical research on resinbased composite in Class II locations started in 1968, although it was crude research compared with the studies of today. It is well-known that those early restorations soon failed because of excessive wear, tooth sensitivity and/or pulpal death, recurrent caries, open contact areas or fracture of the restorative material. Although there are some earlier exceptions, by about 1985

202

nearly 20 years after the introduction of resin-based composite as a Class II restorative materialimproved resin-based composite materials with small particle-sized fillers became commonly used. Successful Class II composite restorations started to be observed and accepted by the profession. Failure still was observed frequently in some brands. The most common causes of failure still were excessive wear, postoperative tooth sensitivity, open contact areas and recurrent caries.3 By now, resin-based composite materials have evolved to the level that properly placed restorations are serving successfully for many years. These restorations require extreme care during placement, including meticulous techniques to prevent postoperative tooth sensitivity, open contacts and the dreaded white line at margins, which generally is related to relaxation of polymerization shrinkage stress in the tooth structure caused by aggressive finishing techniques. How long should a Class II resin-based composite restoration serve when current brands of composite are used and the clinical expertise of the clinician is at least average? It has been our observation in worldwide clinical studies conducted on Class II resin-based composite restorations that predictions for longevity range widely. My own observation about the treatment of dentists who have average or higher clinical ability is that the restorations serve clinically at least 10 years. The current generation of Class II resin-based composites has similar, but less frequent, failure modes to those described previously for the older generations of materials.

Improved materials and enlightened and experienced practitioners have reduced failures significantly during the past few years. However, most clinicians agree that placement of Class II composite restorations requires more careful attention to detail than does placement of similarly sized amalgam restorations. In my opinion, resin-based composite used in Class II situations still needs two improvements. Polymerization shrinkage needs to be reduced to as close to zero as possible, thus reducing stress in remaining tooth structure, and wear of the resin needs to be improved to be close to that of enamel. Manufacturers are working to improve these properties. Porcelain-fused-to-metal (PFM) crowns. These relatively esthetically acceptable restorations have served the public for more than 40 years.4 They are easily made by technicians of average ability, and the tooth preparation and scaling procedures are simple. However, they abrade opposing tooth structure significantly, lose their superficially applied stains within a few years, and become esthetically less acceptable as gingiva recedes. It is my own conclusion that PFM crowns have an esthetic longevity of about 10 years, and because of the degeneration described previously, they have a functional longevity of about 20 years. It is apparent that PFM crowns cost patients significantly more per year of service than do crowns of amalgam or resinbased composite, since the average cost of a PFM crown is about five or six times more than that of an amalgam or composite crown. PFM crowns are relatively

JADA, Vol. 136, February 2005 Copyright 2005 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

OBSERVATIONS

trouble-free. Their most common modes of failure are infrequent fracture of pieces of fired ceramic from the metal understructure, recurrent caries on the margin areas or need for endodontic therapy. Additionally, as expected during a period of years, gingival recession occurs, and esthetically unacceptable PFM crown margins are exposed to view. Cast gold alloy restorations. The lost-wax cast gold restoration has served the public for more than 100 years. However, in recent years, patients have objected to display of gold in their teeth, and use of cast gold alloy restorationsincluding inlays, onlays and crownsis diminishing.5 This trend is disturbing, because any practitioner experienced in the use of cast gold alloy restorations knows that these restorations can be placed with minimal display of metal and serve well for several decades. In my own practice experience, I have seen many of these restorations serve for more than 40 years. Although cast gold alloy restorations can be placed with minimal display of gold alloy, the trend is for patients to reject any display of metal. It is remarkable that most dentists I treat prefer gold alloy restorations in their own posterior teeth, but they place PFM restorations in the teeth of most of their patients. In locations of the mouth where the display of metal can be kept to a minimum, cast gold alloy restorations have no peer with regard to long-term service and minimal wear of opposing teeth, and their use is encouraged. The mode of failure of cast

gold alloy restorations is predictable: wear of the metal through to underlying tooth structure, recurrent caries and, in the case of inlays, occasional fracture of remaining tooth cusps. All-ceramic restorations. All-ceramic restorations for posterior teeth have had an unpredictable service record when used as inlays, onlays, crowns and fixed prostheses. During the past several decades, numerous all-ceramic posterior tooth restoration types have come and gone because of frequent failure. Notable exceptions are the pressed-ceramic restorations and the computer-directed milledceramic restorations, which have had an acceptable service record with observable but minimal failure when placed properly.6 It is impossible to extrapolate an expected overall generic longevity for all-ceramic posterior tooth restorations because of the varied physical characteristics among the types of materials. Currently, several brands of computer-directed milled zirconia substructure, all-ceramic crowns and fixed prostheses are on the international marketplace. In terms of in vitro strength, it is easy to predict that the service potential of these restorations may rival that of PFM crowns. Longer and indepth clinical research is needed to make valid predictions about the longevity potential of these restorations. However, the strength characteristics of the current generation of zirconiabased all-ceramic crowns and fixed prostheses make the predictions for future longevity

highly promising. The failure mode of the older all-ceramic restorations is wellknown. It usually is catastrophic fracture of the complete structure. It is the hope of the profession that the newer generation of these restorations will have significantly better service potential. Until these restorations have proven positive longevity characteristics, patients should be informed about their unpredictable longevity potential.

SUMMARY

Several forms of restorative techniques are used for posterior teeth. They vary significantly in cost and longevity. The following restorative concepts are the most commonly used: amalgam, resinbased composite, PFM, cast gold alloy restorations and allceramic restorations. I suggest that patients be informed about the potential longevity of restorative treatment for posterior teeth as they make decisions about treatment for their oral restorative needs. s

Dr. Christensen is co-founder and senior consultant, Clinical Research Associates, 3707 N. Canyon Road, Suite 3D, Provo, Utah 84604. Address reprint requests to Dr. Christensen. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or official policies of the American Dental Association. 1. Christensen GJ. Informing patients about treatment alternatives. JADA 1999;130: 869-70. 2. Christensen GJ. Amalgam vs. composite resin1998. JADA 1998;129:1757-9. 3. Christensen GJ. Preventing sensitivity in Class II resin restorations. JADA 2001;129: 1469-70. 4. Christensen GJ. Porcelain-fused-to-metal vs. nonmetal crowns. JADA 1999;130:409-11. 5. Christensen GJ. Cast gold restorations: has the esthetic dentistry pendulum swung too far? JADA 2001;132:809-11. 6. Christensen GJ. The confusing array of tooth-colored crowns. JADA 2003;134:1253-5.

JADA, Vol. 136, February 2005 Copyright 2005 American Dental Association. All rights reserved.

203

Você também pode gostar

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- 174 519 1 PBDocumento4 páginas174 519 1 PBDwi Wahyu ArsitaAinda não há avaliações

- LabelsDocumento1 páginaLabelsNavi GadeAinda não há avaliações

- Apex LocatorDocumento5 páginasApex LocatorNavi GadeAinda não há avaliações

- In Vitro Inhibition of Caries-Like Lesions: With Fluoride-Releasing MaterialsDocumento6 páginasIn Vitro Inhibition of Caries-Like Lesions: With Fluoride-Releasing MaterialsNavi GadeAinda não há avaliações

- Slavin 1996Documento6 páginasSlavin 1996jahdsdjad asffdhsajhajdkAinda não há avaliações

- 10kCdz5YW-djkylc0QnB YNo5hs4Vfe9zDocumento45 páginas10kCdz5YW-djkylc0QnB YNo5hs4Vfe9zwangchengching29Ainda não há avaliações

- Efficacy and Safety of Rabeprazole in Children.20Documento10 páginasEfficacy and Safety of Rabeprazole in Children.20Ismy HoiriyahAinda não há avaliações

- Pediatrics Annual ConventionDocumento6 páginasPediatrics Annual ConventionDelOmisolAinda não há avaliações

- Rohini 59284010117Documento21 páginasRohini 59284010117narasimmanbiomedicalAinda não há avaliações

- HYDRONEPHROSISDocumento43 páginasHYDRONEPHROSISEureka RathinamAinda não há avaliações

- Rotator Cuff TendonitisDocumento1 páginaRotator Cuff TendonitisenadAinda não há avaliações

- Benazepril Hydrochloride (Drug Study)Documento3 páginasBenazepril Hydrochloride (Drug Study)Franz.thenurse6888100% (1)

- Manage Preterm Labor with Bed Rest and TocolysisDocumento4 páginasManage Preterm Labor with Bed Rest and TocolysisYeni PuspitaAinda não há avaliações

- REFKAS - Dr. LusitoDocumento43 páginasREFKAS - Dr. LusitoRizal LuthfiAinda não há avaliações

- Asthma Inhale and ExhaleDocumento14 páginasAsthma Inhale and ExhaleNguyen Nhu VinhAinda não há avaliações

- Fast Paces Academy - SymptomsDocumento21 páginasFast Paces Academy - SymptomsAdil ShabbirAinda não há avaliações

- Eight Hallmarks of Cancer ExplainedDocumento40 páginasEight Hallmarks of Cancer ExplainedArnab KalitaAinda não há avaliações

- Use of Local and Axial Pattern Flaps For Reconstruction of The Hard and Soft Palate PDFDocumento9 páginasUse of Local and Axial Pattern Flaps For Reconstruction of The Hard and Soft Palate PDFJose Luis Granados SolerAinda não há avaliações

- Antibiotic Pocket GuideDocumento19 páginasAntibiotic Pocket GuideNaomi Liang100% (1)

- Muhammad YounasDocumento4 páginasMuhammad YounasHamid IqbalAinda não há avaliações

- Committee: World Health Organization Agenda: Prevention and Cure For HIV AIDS Name: John Carlo H. Babasa Delegate of OmanDocumento2 páginasCommittee: World Health Organization Agenda: Prevention and Cure For HIV AIDS Name: John Carlo H. Babasa Delegate of OmanGrinty BabuAinda não há avaliações

- Type III Radix Entomolaris in Permanent Mandibular Second MolarDocumento3 páginasType III Radix Entomolaris in Permanent Mandibular Second MolarGJR PUBLICATIONAinda não há avaliações

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State in Adults: TreatmentDocumento35 páginasDiabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State in Adults: TreatmentyorghiLAinda não há avaliações

- Ophthalmology Set 8Documento5 páginasOphthalmology Set 8ajay khadeAinda não há avaliações

- Peripheral Arterial DiseaseDocumento38 páginasPeripheral Arterial DiseaseRessy HastoprajaAinda não há avaliações

- Stem Cells and Cancer Stem Cells, Volume 2 - Stem Cells and Cancer Stem Cells, Therapeutic Applications in Disease and Injury - Volume 2Documento409 páginasStem Cells and Cancer Stem Cells, Volume 2 - Stem Cells and Cancer Stem Cells, Therapeutic Applications in Disease and Injury - Volume 2ArtanAinda não há avaliações

- NS Compounding Set 4 PDFDocumento24 páginasNS Compounding Set 4 PDFJulia BottiniAinda não há avaliações

- Certificate For COVID-19 Vaccination: Beneficiary DetailsDocumento1 páginaCertificate For COVID-19 Vaccination: Beneficiary DetailsAshok KumarAinda não há avaliações

- What Are The 4 Types of Food Contamination? - Food Safety GuideDocumento6 páginasWhat Are The 4 Types of Food Contamination? - Food Safety GuideA.Ainda não há avaliações

- Congenital Anatomic AnomaliesDocumento12 páginasCongenital Anatomic Anomaliesmahparah_mumtazAinda não há avaliações

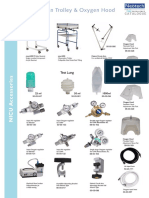

- Nice Neotech - Accessories - 20Documento1 páginaNice Neotech - Accessories - 20David Gnana DuraiAinda não há avaliações

- Upper Extremity Venous Doppler Ultrasound PDFDocumento12 páginasUpper Extremity Venous Doppler Ultrasound PDFLayla Salomão0% (1)

- Winkler - Chapter 8. Khalid AlshareefDocumento4 páginasWinkler - Chapter 8. Khalid AlshareefKhalid Bin FaisalAinda não há avaliações

- Chronology of Human Dentition & Tooth Numbering SystemDocumento54 páginasChronology of Human Dentition & Tooth Numbering Systemdr parveen bathla100% (4)