Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Bike Lane Dimension Guidelines

Enviado por

Jerwin Domingo GonzalesDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Bike Lane Dimension Guidelines

Enviado por

Jerwin Domingo GonzalesDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

This bike lane has enough width for a bicyclist to comfortably ride between the curb and gutter

and the adjacent travel lane.

Bike lanes are defined as "a portion of the roadway which has been designated by striping, signing and pavement marking for the preferential or exclusive use by bicyclists". Bicycle lanes make the movements of both motorists and bicyclists more predictable and as with other bicycle facilities there are advantages to all road users in striping them on the roadway. Bicycle-friendly cities such as Madison, Eugene, Davis, Gainesville, and Palo Alto have developed extensive bike lane networks since the 1970s and more recently large cities such as Tucson, Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia, Portland and Seattle have begun to stripe bike lanes on their arterial and collector streets as a way of encouraging bicycle use. In general, bicycle lanes should always be:

one-way, carrying bicyclists in the same direction as the adjacent travel lane on the right side of the roadway located between the parking lane (if there is one) and the travel lane

Critical dimensions

Bicycle lane width (AASHTO Guide, pp. 2224):

4 feet (1.2m): minimum width of bike lane on roadways with no curb and gutter 5 feet (1.5m): minimum width of bike lane when adjacent to parking, from the face of the curb or guardrail 11 feet (3.3m): total width for shared bike lane and parking area, no curb face 12 feet (3.6m): shared bike lane and parking area with a curb face

Bicycle lane stripe width:

6-inch (150mm): solid white line separating bike lane from motor vehicle lane (possibly increased to 8-inches (200mm) where emphasis is needed)

4-inch (100mm): optional solid white line separating the bike lane from parking spaces

Critical Issues and Frequently Asked Questions

How can I fit bike lanes onto a 44 ft wide urban road? The City of Chicago, among others, is successfully striping 44ft roadways with two seven foot parking lanes, two five foot bike lanes and two ten foot travel lanes. My city engineer says he can't reduce travel lanes below the AASHTO recommended width of 12 feet. Is that true? No. In fact, the new AASHTO Guide for the Development of Bicycle Facilities says "another important reason for constructing bike lanes is to better accommodate bicyclists where insufficient space exists for comfortable riding on existing streets. This may be accomplished by reducing the width of vehicular lanes or prohibiting parking...". The Oregon Department of Transportation bicycle plan has an extensive section on restriping existing streets to incorporate bike lanes. I am not sure a white paint line is enough. Can I use raised pavement markers or some kind of barrier or curb to separate the bike lane from motor vehicles? Studies have shown that a simple white line is actually quite effective in channelizing both motorists and bicyclists and that both feel more comfortable with the line in place. Raised pavement markers can cause a cyclist to lose control and fall; barriers and curbs also prevent bicyclists from avoiding obstacles (or even passing another cyclist) and making a left turn, and make maintenance much more challenging (and unlikely).

Innovative bike lane designs

There are a number of innovative bike lane designs that have been tried and tested to overcome particular barriers to bicycling, or to solve a problem in a particular location.

Contraflow bike lanes

While bike lanes should normally carry bicyclists in the direction of traffic, there are some locations where there is a strong demand for bicyclists to travel against the normal flow of traffic, or to travel in both directions on a one-way street. For example, University Avenue in Madison, Wis., runs through the heart of the University of Wisconsin campus can carries heavy flows of bicyclists and other road users. Because of the high demand for bicycle travel in both directions, several years ago the road was rebuilt with a bus lane, bike lane and three travel

lanes in one direction and a bike lane only (separated by a raised median) in the other direction. A number of communities have created short segments of contraflow bike lanes in order to provide bicyclists unique access to residential streets. For example, the cities of Madison and Portland have both used this technique to open up a network of routes on residential streets that are not accessible in both directions both motor vehicle-essentially creating a very short stretch of roadway that is two-way for bikes but only one-way for cars.

Colored bike lanes

Colored bike lanes have been a feature of bicycle infrastructure in the Netherlands (red), Denmark (blue), France (green) and many other countries for many years. In the United Kingdom, both red and green pigments are used to delineate bike lanes and bike boxes. However, in this country their use has been limited to a few experiments in just a handful of locations. The most extensive trial took place in Portland, Ore., where a number of critical intersections had blue bike lanes marked through them and the results were carefully monitored. The results of the study, conducted by the City of Portland Office of Transportation and the UNC Highway Safety Research Center, can be found here.

Shared bike and bus lanes

A growing number of communities are using shared bus and bike lanes to give preferential treatment to both bikes and public transport. Examples currently include Tucson, AZ; Madison, WI; Toronto, Ontario; Vancouver, BC; and Philadelphia, PA. Often the lanes are also able to be used by taxis and rightturning vehicles. Because buses and bikes will pass each other in these lanes, lane width is an important issue. The city of Madison likes to use 16 foot lanes to allow a clear three feet of separation between the bicyclist and a passing bus, but if either bus or bike traffic is light and space is limited, the width of a shared lane might be 14 feet or even less.

Você também pode gostar

- Transit Street Design GuideNo EverandTransit Street Design GuideAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 4 Final DraftDocumento8 páginasUnit 4 Final Draftapi-242400414Ainda não há avaliações

- Urban Bikeway Design Guide, Second EditionNo EverandUrban Bikeway Design Guide, Second EditionNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Healthy Transport Project: English IVDocumento13 páginasHealthy Transport Project: English IVJosafat Vargas CuetoAinda não há avaliações

- Collingswood Bike Lane StudyDocumento40 páginasCollingswood Bike Lane StudyJohn BoyleAinda não há avaliações

- WABA Bikeshare MemoDocumento2 páginasWABA Bikeshare MemotonalblueAinda não há avaliações

- CH 04Documento20 páginasCH 04duupzAinda não há avaliações

- Separated Bike Lanes v. Shared Use PathsDocumento3 páginasSeparated Bike Lanes v. Shared Use PathsM-NCPPCAinda não há avaliações

- Testimony of The Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia On Philadelphia's 2013 BudgetDocumento7 páginasTestimony of The Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia On Philadelphia's 2013 Budgetsarah8328Ainda não há avaliações

- BackgroundDocumento16 páginasBackgroundMekdelawit GirmayAinda não há avaliações

- Cycle Track Lessons LearnedDocumento18 páginasCycle Track Lessons LearnedHara GravaniAinda não há avaliações

- Integrated Bike LanesDocumento20 páginasIntegrated Bike Lanesuntung CahyadiAinda não há avaliações

- CM Position Paper - Cyclists and SidewalksDocumento3 páginasCM Position Paper - Cyclists and SidewalksTom BradfordAinda não há avaliações

- Planning For NMT in CitiesDocumento53 páginasPlanning For NMT in CitiesShaharyar AtiqueAinda não há avaliações

- Two-Way Bikeways On Both Sides of The Street: Domestic ExamplesDocumento5 páginasTwo-Way Bikeways On Both Sides of The Street: Domestic ExamplesM-NCPPCAinda não há avaliações

- Montgomery County Bicycle Planning Guidance: July 2014Documento18 páginasMontgomery County Bicycle Planning Guidance: July 2014M-NCPPCAinda não há avaliações

- Tonight'S Agenda:: 1. Sign in 2. Open House 3. Presentation at 7:20 P.MDocumento14 páginasTonight'S Agenda:: 1. Sign in 2. Open House 3. Presentation at 7:20 P.MM-NCPPCAinda não há avaliações

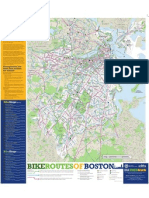

- Boston Bike Map tcm3-14074Documento2 páginasBoston Bike Map tcm3-14074api-166112125Ainda não há avaliações

- Why Do We Need A Bike Lane On Madison?Documento8 páginasWhy Do We Need A Bike Lane On Madison?lkwdcitizenAinda não há avaliações

- Cs Brochure FeaturesDocumento2 páginasCs Brochure FeaturesClaudio Sarmiento CasasAinda não há avaliações

- Pedestrian Facility DesignDocumento9 páginasPedestrian Facility DesignTáo NguyễnAinda não há avaliações

- Pedestrian and Bicycle Circulation: Pennsylvania Standards For Residential Site Development: April 2007Documento30 páginasPedestrian and Bicycle Circulation: Pennsylvania Standards For Residential Site Development: April 2007kasandra01Ainda não há avaliações

- Vehicle Travel Lane Width Guidelines Jan2015Documento15 páginasVehicle Travel Lane Width Guidelines Jan2015Hermann PankowAinda não há avaliações

- Docs CDocumento15 páginasDocs CJobelle RafaelAinda não há avaliações

- Sidewalk Biking FAQDocumento6 páginasSidewalk Biking FAQjoeyjoejoeAinda não há avaliações

- Interested But Concerned Riders, Those Who Are Less Comfortable Riding in An Unprotected Facility OnDocumento4 páginasInterested But Concerned Riders, Those Who Are Less Comfortable Riding in An Unprotected Facility OnM-NCPPCAinda não há avaliações

- Way or Two-Way: Vehicles On One-Way Streets May Travel in Only One Direction, While Those On TwoDocumento1 páginaWay or Two-Way: Vehicles On One-Way Streets May Travel in Only One Direction, While Those On Two16SA125.KaranThakkarAinda não há avaliações

- American Bicycle-Sharing NetworksDocumento30 páginasAmerican Bicycle-Sharing Networkssjacobsen09Ainda não há avaliações

- Bike Plan Appendices PG 12 For ImportanceDocumento194 páginasBike Plan Appendices PG 12 For ImportanceMark DonahoAinda não há avaliações

- MoMaP Design Guidelines - FinalDocumento102 páginasMoMaP Design Guidelines - FinalnaimshaikhAinda não há avaliações

- Bicycle Letter - MobleyDocumento2 páginasBicycle Letter - MobleytonalblueAinda não há avaliações

- Arlington Boulevard Trail Concept PlanDocumento25 páginasArlington Boulevard Trail Concept Planwabadc100% (2)

- Sharing The StreetDocumento3 páginasSharing The StreetScott M. StringerAinda não há avaliações

- Pedestrian and Bicycle Activities in The Life Sciences Center AreaDocumento99 páginasPedestrian and Bicycle Activities in The Life Sciences Center AreaM-NCPPCAinda não há avaliações

- Bicycle and Pedestrian Planning and DesignDocumento67 páginasBicycle and Pedestrian Planning and Designsherifgeb1Ainda não há avaliações

- Getting Started GuideDocumento8 páginasGetting Started GuideHeidi SimonAinda não há avaliações

- CHAPTER 123 JimenezDocumento4 páginasCHAPTER 123 JimenezasdwqeAinda não há avaliações

- Committee LetterDocumento2 páginasCommittee LetterYan BennettAinda não há avaliações

- WeMove Fact SheetDocumento1 páginaWeMove Fact SheetwabadcAinda não há avaliações

- Ebarnum 6Documento12 páginasEbarnum 6api-656458162Ainda não há avaliações

- Cycle Tracks: DescriptionDocumento5 páginasCycle Tracks: Descriptionpranshu speedyAinda não há avaliações

- Route Planning National Association of City Transportation OfficialsDocumento9 páginasRoute Planning National Association of City Transportation OfficialsJav BarriosAinda não há avaliações

- Electric Cargo BicycleDocumento43 páginasElectric Cargo BicycleNAg RAjAinda não há avaliações

- Complete StreetsDocumento2 páginasComplete StreetsHeidi SimonAinda não há avaliações

- Stakeholder Presentation: Steve DurrantDocumento34 páginasStakeholder Presentation: Steve DurranttfooqAinda não há avaliações

- Aashto Bicycle Lanes PDFDocumento10 páginasAashto Bicycle Lanes PDFJohnny Jr TumangdayAinda não há avaliações

- 10.0 Summary and ConclusionsDocumento10 páginas10.0 Summary and ConclusionsdurgaAinda não há avaliações

- Traffic Safety Strategy: Town of StratfordDocumento22 páginasTraffic Safety Strategy: Town of StratfordGranicus CivicIdeasAinda não há avaliações

- The Need For Bicycle and Pedestrian Mobility: 1.1 PurposeDocumento18 páginasThe Need For Bicycle and Pedestrian Mobility: 1.1 PurposeMaria TudorAinda não há avaliações

- Bicycle and Pedestrian Connections and AmenitiesDocumento7 páginasBicycle and Pedestrian Connections and AmenitiestfooqAinda não há avaliações

- Aberdeen Chapter6Documento40 páginasAberdeen Chapter6Arch AmiAinda não há avaliações

- Risk Factors IdentificationDocumento3 páginasRisk Factors IdentificationAYADAinda não há avaliações

- Soknacki Transportation Relief Plan: Part 3 - Transportation Policy Beyond TransitDocumento9 páginasSoknacki Transportation Relief Plan: Part 3 - Transportation Policy Beyond TransitDavid Soknacki CampaignAinda não há avaliações

- BikelanesDocumento7 páginasBikelanesapi-228164502Ainda não há avaliações

- Civic Center Contraflow Factsheet 9-17-15Documento1 páginaCivic Center Contraflow Factsheet 9-17-15John BoyleAinda não há avaliações

- Road Interchange Student ResearchDocumento12 páginasRoad Interchange Student ResearchKookie BTS100% (1)

- All About Roundabouts BrochureDocumento2 páginasAll About Roundabouts BrochureNikola MiticAinda não há avaliações

- Cross-Section LecturenotesDocumento14 páginasCross-Section LecturenotesAhmad Fauzan Ahmad MalikiAinda não há avaliações

- Arch 315 QF - 5Documento3 páginasArch 315 QF - 5MARRIAH ELIZZA FERNANDEZAinda não há avaliações

- Manual de Carroceria para Camiones HINO Linea 300 XZU Y XKU PDFDocumento277 páginasManual de Carroceria para Camiones HINO Linea 300 XZU Y XKU PDFjhon jairo90% (10)

- Prestige Park GroveDocumento6 páginasPrestige Park GrovePrestige Park GroveAinda não há avaliações

- PROWAG - Accessibility GuidelinesDocumento114 páginasPROWAG - Accessibility GuidelinesSlim ShadyAinda não há avaliações

- Urban Design Image of The City Doha-Qatar: 101117009 Divya Ramaseshan Assignment 2Documento17 páginasUrban Design Image of The City Doha-Qatar: 101117009 Divya Ramaseshan Assignment 2RoopendraKumarAinda não há avaliações

- Damodaram Sanjivayya National Law - TPADocumento24 páginasDamodaram Sanjivayya National Law - TPAMugdha TomarAinda não há avaliações

- Movable BridgeDocumento263 páginasMovable BridgeCharbel Ghanem100% (1)

- BU VOL III Schedule (A-D) - Package-ADocumento44 páginasBU VOL III Schedule (A-D) - Package-AA MAinda não há avaliações

- A Summary of DRAFT Master PlanDocumento16 páginasA Summary of DRAFT Master Planakhilchibber100% (1)

- Bridge Engineering DesignDocumento13 páginasBridge Engineering DesignRowland Adewumi100% (60)

- AD122 Map PublicationDocumento1 páginaAD122 Map Publicationgluck_samuelAinda não há avaliações

- TM - Master DataDocumento2 páginasTM - Master DataunverAinda não há avaliações

- SF9 XCR LoDocumento1 páginaSF9 XCR Losoleni4Ainda não há avaliações

- Contrast2 AIO Extension AKDocumento4 páginasContrast2 AIO Extension AKcmvvmc0% (1)

- ECE Regulation No 055 Rev 01Documento81 páginasECE Regulation No 055 Rev 01Zo StevanovicAinda não há avaliações

- Affidavit of Loss Drivers LicenseDocumento2 páginasAffidavit of Loss Drivers LicenseBembol MirasolAinda não há avaliações

- DPWH Standard Specification (2004 Edition)Documento147 páginasDPWH Standard Specification (2004 Edition)Jasper Kenneth Peralta100% (4)

- Peter Tuft - As2885 Pipe Wall ThicknessDocumento34 páginasPeter Tuft - As2885 Pipe Wall ThicknessNuzul Furqony0% (1)

- 2008 Jeep Liberty BrochureDocumento34 páginas2008 Jeep Liberty Brochureswift100% (7)

- TSMG-Chemical Logistics in IndiaDocumento24 páginasTSMG-Chemical Logistics in IndiaanweshaccAinda não há avaliações

- Khaleej Dubai UpdatedDocumento78 páginasKhaleej Dubai Updatedkhaleejdubai jubailAinda não há avaliações

- Building and Infrastructure Company Profile Sample PDFDocumento11 páginasBuilding and Infrastructure Company Profile Sample PDFKevin Marc BabateAinda não há avaliações

- Load Rating of Steel Bridges: Steel Bridge Design HandbookDocumento28 páginasLoad Rating of Steel Bridges: Steel Bridge Design HandbookIsrael Castillo AltamiranoAinda não há avaliações

- First Aid KitDocumento6 páginasFirst Aid KitBiondi TeAinda não há avaliações

- Seminar Report Rohit JainDocumento49 páginasSeminar Report Rohit JainAshish Rawat25% (4)

- 1.1 Overview: Data Mining Based Risk Estimation of Road AccidentsDocumento61 páginas1.1 Overview: Data Mining Based Risk Estimation of Road AccidentsHarshitha KhandelwalAinda não há avaliações

- Road MarkingDocumento6 páginasRoad MarkingPanchadcharam PushparubanAinda não há avaliações

- 4.3 Site Preparation: WWW - Epa.gov/owow/nps/lid/lidnatl. PDF Publicworks/planningdesign/bmpindex - HTMDocumento17 páginas4.3 Site Preparation: WWW - Epa.gov/owow/nps/lid/lidnatl. PDF Publicworks/planningdesign/bmpindex - HTMAnonymous pFXVbOS9TWAinda não há avaliações

- Well FoundationDocumento56 páginasWell FoundationSriram Nandipati67% (3)

- Endure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human PerformanceNo EverandEndure: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human PerformanceNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (237)

- Eat & Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon GreatnessNo EverandEat & Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon GreatnessAinda não há avaliações

- Whole Body Barefoot: Transitioning Well to Minimal FootwearNo EverandWhole Body Barefoot: Transitioning Well to Minimal FootwearNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (16)

- Mind Gym: An Athlete's Guide to Inner ExcellenceNo EverandMind Gym: An Athlete's Guide to Inner ExcellenceNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (18)

- Can't Nothing Bring Me Down: Chasing Myself in the Race Against TimeNo EverandCan't Nothing Bring Me Down: Chasing Myself in the Race Against TimeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamNo EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (59)

- Run the Mile You're In: Finding God in Every StepNo EverandRun the Mile You're In: Finding God in Every StepNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (72)

- Long Road to Boston: The Pursuit of the World's Most Coveted MarathonNo EverandLong Road to Boston: The Pursuit of the World's Most Coveted MarathonNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- The Inner Runner: Running to a More Successful, Creative, and Confident YouNo EverandThe Inner Runner: Running to a More Successful, Creative, and Confident YouNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (61)

- 80/20 Running: Run Stronger and Race Faster by Training SlowerNo Everand80/20 Running: Run Stronger and Race Faster by Training SlowerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (97)

- Training for the Uphill Athlete: A Manual for Mountain Runners and Ski MountaineersNo EverandTraining for the Uphill Athlete: A Manual for Mountain Runners and Ski MountaineersNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (13)

- Whole Body Barefoot: Transitioning Well To Minimal FootwearNo EverandWhole Body Barefoot: Transitioning Well To Minimal FootwearNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (33)

- Sick to Fit: 3 Simple Techniques that Got Me from 420 Pounds to the Cover of Runner's World, Good Morning America, and The Today ShowNo EverandSick to Fit: 3 Simple Techniques that Got Me from 420 Pounds to the Cover of Runner's World, Good Morning America, and The Today ShowNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (6)

- Your Pace or Mine?: What Running Taught Me About Life, Laughter and Coming LastNo EverandYour Pace or Mine?: What Running Taught Me About Life, Laughter and Coming LastNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (27)

- Strength Training For Runners : The Best Forms of Weight Training for RunnersNo EverandStrength Training For Runners : The Best Forms of Weight Training for RunnersNota: 2 de 5 estrelas2/5 (5)

- Above the Clouds: How I Carved My Own Path to the Top of the WorldNo EverandAbove the Clouds: How I Carved My Own Path to the Top of the WorldNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (25)

- Depression Hates a Moving Target: How Running With My Dog Brought Me Back From the BrinkNo EverandDepression Hates a Moving Target: How Running With My Dog Brought Me Back From the BrinkNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (35)

- Eat And Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon GreatnessNo EverandEat And Run: My Unlikely Journey to Ultramarathon GreatnessNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (23)

- The Pants Of Perspective: One woman's 3,000 kilometre running adventure through the wilds of New ZealandNo EverandThe Pants Of Perspective: One woman's 3,000 kilometre running adventure through the wilds of New ZealandNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (82)

- 80/20 Running: The Ultimate Guide to the Art of Running, Discover How Running Can Help You Improve Your Fitness, Lose Weight and Improve Your Overall HealthNo Everand80/20 Running: The Ultimate Guide to the Art of Running, Discover How Running Can Help You Improve Your Fitness, Lose Weight and Improve Your Overall HealthNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (53)

- Hansons Marathon Method: Run Your Fastest Marathon the Hansons WayNo EverandHansons Marathon Method: Run Your Fastest Marathon the Hansons WayNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (3)

- How to Run a Marathon: The Go-to Guide for Anyone and EveryoneNo EverandHow to Run a Marathon: The Go-to Guide for Anyone and EveryoneNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (17)

- In the Spell of the Barkley: Unravelling the Mystery of the World's Toughest UltramarathonNo EverandIn the Spell of the Barkley: Unravelling the Mystery of the World's Toughest UltramarathonAinda não há avaliações