Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Introduction From Selling Cromwell's Wars

Enviado por

Pickering and ChattoDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Introduction From Selling Cromwell's Wars

Enviado por

Pickering and ChattoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

INTRODUCTION

Months after its inception, the new English Commonwealth embarked on a series of wars. Beginning with the invasion of Ireland in 1649, the republic moved on to the invasion of Scotland in 1650 and the first Anglo-Dutch war in 1652. The Cromwellian Protectorate continued in this vein, undertaking the Western Design and Anglo-Spanish war in 1655. For a time it appeared Cromwell might intervene in religious conflicts on the continent as well. This book examines the ways in which the media shaped and marketed war, empire and political policies in the 1650s. In so doing this study also explores the interrelation of news, print and political cultures and the conduct of public debate. To enable close analysis of these relationships and strategies the book focuses on a series of case studies: the establishment of the republic; the Cromwellian invasion and conquest of Scotland; imperialism, the Western Design and the conquest of Jamaica; the broader Anglo-Spanish war stretching across both sides of the Atlantic; and international religious conflict. Exploration of these different episodes affords an excellent opportunity to examine the ways the media shaped, and were shaped by, political developments and concerns. These were controversial wars and the regimes of the 1650s hoped to maximize popular support. In selling these wars, the media were instrumental. In studying war one of the first questions historians tend to ask is: What was the conflict about? To answer this question it is common for historians to try to tease out the true motives and aspirations of politicians and military men. Such efforts have produced lively debates over Cromwells aims and intentions in war and empire. One particular point of scholarly conflict has been the role of religion in Cromwells foreign and imperial policies: were his religious goals sincere, or did he use religious rhetoric to camouflage underlying strategic and economic aims? Historians have reached differing conclusions.1 In part this is due to the nature of the extant source material. While Cromwell generated a large number of official documents, correspondence and directives, he left few unofficial personal accounts and reflections and no diary or journal. There are also gaps in available materials, including the records of the Protectoral Council of State. As a result, Peter Gaunt has argued, it is ultimately impossible to ascer-

Copyright

Selling Cromwells Wars

Copyright

tain whether or not Cromwell had formulated coherent long-term policies.2 That Cromwells true motivations can be identified, uncovered and measured poses another historical and methodological problem. Scholars have sought to disentangle Cromwells public representations of war from his private intentions and assess the extent to which the two were in agreement. This suggests layers of rhetoric can be sloughed off to reveal an underlying and intact truth, that public justifications of war can be separated from a reality that exists apart from their representation.3 A division between public and private motivations raises several issues. Truth is presumed to reside in the latter: there were actual reasons, to which the public may or may not have been privy, for war that can be distinguished from public pronouncements. It assumes that we can determine authentic, inner motivations with any certainty, despite incomplete records and without reference to the language and context in which motivations were expressed. It requires some expectation that motivations remain stable over time and therefore can be subject to measurement. It also equates motives for war with the intentions and goals of political and military officials. For seventeenth-century men and women, however, understanding what a particular war was about did not necessarily have much to do with what was going on in the hearts and minds of politicians. Most contemporaries did not have access to politicians inner lives, and indeed may not have cared tremendously if they had. More importantly, the determination of what war was about was not restricted to political and military leaders. Rather, the media played a vital role in promoting, interpreting and debating war. This process was not a linear one, with journalists, editors and pamphleteers simply giving voice to the motives and aims of politicians. Rather, media sources themselves shaped political, foreign and imperial policies and engaged in public debate. Journalists and pamphleteers responded to events as they unfolded, placed current developments in historical and ideological context and sought to persuade audiences of right interpretation. For these reasons it is important to examine not just what actually happened but, as Peter Lake and Steven Pincus have put it, also the stories people told about what was happening.4 The term media is used here to signify various forms of print, manuscript, oral and visual communication which in turn were interconnected. News, for example, was transmitted in several ways: through printed newsbooks and pamphlets, in manuscript and verbally. These types of communication can be broken down further. Manuscript news, for example, could take such forms as newsletters, intelligence reports, military and diplomatic dispatches, official letters and personal correspondence. Much of the written news media tended to be proprietary, geared primarily to specific networks of correspondents. Yet news gleaned from manuscript sources often reached print in newsbooks and pamphlets, which widened its distribution. Printed news would recirculate orally

Introduction

and in manuscript, and verbal news, rumour and gossip often made their way into printed and manuscript sources. The boundaries separating different news media thus were porous. More generally, the distinctions among print, written and oral cultures were blurry ones.5 Pamphlets and newsbooks, for example, would be read aloud, giving illiterate and semi-literate men and women access to literate culture. Recognizing the potency of visual images, some texts also contained woodcuts and engravings to graphically illustrate textual material.6 Like the news media, various forms of print media often overlapped as well. Newsbooks, for example, frequently reprinted material published in pamphlets. Some pamphlets contained multiple texts bundled together to enable audiences to trace arguments and follow debates. In this manner, a single text could circulate in multiple venues and formats. A declaration of war, for example, printed or read aloud announced the initiation of armed conflict and justified its conduct. Reprinting a declaration in newsbooks placed it in the context of news and current events, and editorials could further develop the political, religious and historical background to guide interpretation and explain significance. When printed together with rebuttals or other defences of war, the declaration became part of a dialogue or debate. Such practices not only increased the availability of texts and enhanced their accessibility, but they also highlight the ways in which different formats served different polemical purposes and shaped interpretive context. News, print and political cultures thus were intertwined. By the time monarchy had been abolished and the English republic established in 1649, politics had become a public affair. Policy development, political debate, the waging of war and the conclusion of peace, all of which traditionally had been viewed as government prerogatives restricted to the royal court, council and halls of Parliament, had moved into the public arena. Government actions were promoted, evaluated, critiqued and challenged in the press and pulpit, in inns, taverns and coffee houses, in the streets and households of London, Dublin and Edinburgh, in provincial centres and rural parishes, in port and market towns. News was not always accurate or reliable. Then, as now, news could be plagued by false reports (sometimes accidental, sometimes deliberate), rumour and gossip, speculation, spin and sometimes disinformation.7 Reports could go uncorroborated for weeks or months. Stoppage of the post during wartime, for example, or transatlantic travel could cause long delays. It also was customary for journalists and editors to repeat information gleaned from other news outlets.8 This practice could lend reports a sense of authenticity and could perpetuate false news. On the other hand, circulation and repetition helped foster what scholars have variously termed the development of the present and contemporaneity.9 By mid-century, the public appetite for news along with the growth of print culture and availability of cheap pamphlets afforded the opportunity to shape

Copyright

Selling Cromwells Wars

Copyright

opinion and to generate support for political, military and religious policies and objectives.10 This was not a new or original development. Since the sixteenth century, for example, libels had attested to a popular interest in politics and governments increasingly began to appreciate the influence of the media on popular opinion.11 To take one instance, in the 1620s a public relations campaign during the Duke of Buckinghams expedition to the Ile de R demonstrated how favourable spin could resuscitate a flagging career and cause political, military and personal popularity to soar. Conversely, when governments, notably that of Charles I, eschewed such public promotion and policy defence, popular opinion could swing and hinder effective government.12 What set the 1640s apart from previous decades was the sheer size and scale of public debate and campaigns to influence public opinion, which reached unprecedented heights.13 In 1642, following the collapse of licensing regulations, it has been estimated that four million pamphlets and books were in circulation; to put it in concrete terms, for a total English population of about five million there were four books for every five people and ten books per Londoner.14 Pamphlets and newsbooks were cheap and enjoyed extensive circulation. Readily available from hawkers on street corners or stalls at the London Exchange and St Pauls Churchyard, they also were distributed and marketed by itinerant chapmen in the provinces and copies were lent, borrowed and recirculated to broaden their reach further.15 Newsbooks and pamphlets could offer a great advantage to the successive governments of the 1650s in promoting and publicizing policies. At the same time, print also offered outlets for critique, debate and opposition. In September 1649 the republic enacted stricter censorship laws and worked to attain greater control over the press. By the summer of 1650, royalist newsbooks had been all but suppressed.16 Another wave of licensing restrictions took place in the fall of 1655, eliminating virtually all newsbooks but Marchamont Nedhams Mercurius Politicus and his newly created Publick Intelligencer. Numerous institutions and bodies to police print had long been in place, ranging from the Stationers Company to local justices of the peace to military officials, and recently it has been argued that these mechanisms could be much more effective, both actually and potentially, than many scholars have allowed.17 On the whole, however, the governments of the 1650s were reluctant to impose draconian censorship laws. The crackdowns of 1649 and 1655 curbed but certainly did not silence political debate, and opposition to government policies continued in the underground press.18 In the 1650s, among the most regular promoters of government policies and objectives was the state-sponsored journalist and editor Marchamont Nedham.19 His Politicus was the longest-running weekly newsbook, lasting from its first issue in June 1650 to the Restoration in 1660. It was popular and cheap, for sale at about 2d. In October 1655, Nedham added his other newsbook, Pub-

Introduction

lick Intelligencer, which overlapped considerably in content with Politicus; this overlap, however, does not appear to have affected the newsbooks popularity or circulation.20 From its first issue Politicus provided regular endorsements of, and justifications for, government actions and initiatives. Nedham enjoyed a close relationship to John Thurloe, secretary of state and head of British intelligence under the Protectorate. Through Thurloe Nedham had access to intelligence reports, intercepted communications and diplomatic and military correspondence, much of which regularly found its way into the pages of his newsbooks.21 On one level, much of the polemic of the 1650s can be termed official propaganda. Politicus, for example, can be construed as a propaganda vehicle; the newsbook was devised as the mouthpiece of the Commonwealth, and supported every change of regime until its termination in 1660.22 Some texts were produced by professional propagandists commissioned, paid or subsidized by the government. Others were composed in hopes of reward or favour.23 The link to government sponsorship, however, was not always direct or evident. Defence of official policies did not necessarily depend on payment and was not necessarily governmentally orchestrated. Polemicists could use their support of government policies to suit their own purposes. Endorsement, therefore, did not always convey the message officials wanted to send.24 Even paid polemicists, including Nedham, printed material that undermined government interests. Foregrounding links to government sponsors also can limit understanding of how contemporaries might have read or approached such texts. Anonymous and pseudonymous publications divorced author and patron, allowing texts to be read without reference to official commission or sanction. Anonymity and pseudonymity, moreover, were part of the culture of pamphleteering and were not limited to the production of propaganda or controversial literature. Anonymity was a vital convention of public debate: it enabled the text to assume a voice and identity apart from particular contexts, authors and often publishers and printers. Anonymous and pseudonymous publications asked audiences to engage with the content of a text rather than its source. Focus on a texts origins, including attributions of patronage or sponsorship, can minimize or distort textual complexities.25 It can also marginalize critique of and challenges to official policy. Public debate took place in what Jrgen Habermas identified as the public sphere. In Habermass formulation, the public sphere developed in the eighteenth century as a product of capitalist growth and enabled private, middle-class individuals to join together in an open exchange of opinion. Habermass idealized public sphere was governed by reason and opposed to government control and intervention.26 When following the Habermasian model, the government propaganda machine of the 1640s and 1650s can be seen as curbing public debate and preventing the emergence of a public sphere.27 A number of scholars have pushed back the creation of the public sphere to the 1640s and have detected the exist-

Copyright

Selling Cromwells Wars

Copyright

ence of public spheres emerging at various points in previous decades.28 Along with chronological relocation historians and literary scholars have re-envisioned the Habermasian model. The public sphere or spheres of the seventeenth century were not grounded upon a belief in the rational, unfettered exchange of ideas. Appeals to the public and the public interest were put forward by groups on all sides but were not based on an idealized or abstract commitment to open, objective public discussion. Rather, these invocations were fiercely partisan and founded on the conviction that while truth might be disputed, it was nonetheless fathomable.29 Contemporary news and print cultures were built upon the foundation of persuasion. In contrast to the modern ideal of objective reporting, seventeenthcentury editors, journalists and pamphleteers set out not simply to impart information, but to place material in interpretive contexts and to advocate particular points of view. Those interpretations in turn were open to debate. For example, as Ethan Shagan has demonstrated, accounts of the 1641 Irish Rebellion in England produced no automatic or consensual view of its import and reception.30 Persuasion involved a wide range of rhetorical and literary techniques including the refutation of contrary positions, a practice which necessitated the acknowledgement and presentation of competing viewpoints.31 While the intention of the writer was to direct the interpretation of the reader, representing conflicting perspectives could undermine or question as well as strengthen the authors message. There was thus no hegemonic party line and no straightforward, unproblematic imposition of propaganda from above. Instead of manipulating largely passive readers, polemicists sought to actively engage readers in multiple dialogues, not only between the author and reader but also those within and across texts. The roots of what David Zaret has termed this dialogic order were instrumental rather than idealistic in nature, born of the desire to win support for contrary positions rather than out of a belief in participatory government or unrestricted freedom of expression. By the 1640s this transformed political culture, enlisting the public as a collective and active political force to which politicians were accountable.32 The rhetorical, polemical and literary techniques of persuasion, the spin, cannot be weeded out and discarded as embellishments to a text. These were part of the cultures of news, pamphleteering, and politics, and they were at once a vehicle for and inseparable from textual meaning.33 Appealing to readers and the use of persuasive strategies of course were no guarantees that audiences would respond favourably, and indeed many readers were adept at resisting the thrust of polemicists. Nedhams readers, like those of other journalists and pamphleteers, were as likely to be opponents of the regimes and policies he promoted as supporters. Royalists, for example, were avid readers of English newsbooks and pamphlets which they employed as sources of

Introduction

information upon which to base their own political and diplomatic strategies.34 Beyond the general, loose categories of government proponents and detractors, the members of which often were transitory and were far from united, were a multitude of other audiences, including neutral or uncommitted readers, foreign agents, diplomats and intelligence-gatherers. Readers read for different reasons and responded to their reading in different ways. Some read for pleasure, others for information and intelligence, some for spiritual enlightenment and others for political and historical instruction.35 Determining how readers read newsbooks and popular pamphlets presents particular challenges. Little is known about who actual readers were, and many others heard rather than read the news. Readers of popular print tended not to leave records of their responses. Not only is much of the evidence restricted to those who could write and who were moved to comment upon their reading, but because news pamphlets largely responded to, commented upon and assessed current events they tended to be treated as ephemera. Unlike, for example, political and historical treatises, news pamphlets usually were not copied into commonplace books or subjected to extended reflection in diaries.36 Sometimes diarists and letters-writers record their reactions to specific pamphlets identified or identifiable by title or name. For example, Sir Archibald Johnston of Wariston, who accompanied Charles IIs army in Scotland in the summer of 1650, confronted the King about a pamphlet detailing his negotiations with the pope for aid in which he pledged to tolerate Catholics upon his restoration.37 More often, however, writers refer in a more general sense to their reading of the prints, the books, diurnals, or London descriptions.38 For some writers the transmission of news was described primarily as a verbal act. Ralph Josselin, for example, read the bible and commentaries or treatises on Revelation, but he heard news which was said rather than written.39 Verbal language might well indicate actual oral delivery. News, as noted above, was discussed and debated in taverns, coffee houses, and other public places and circulated orally in households and communities. At the same time, the spoken word was believed to carry a special truth-value and a particular ability to persuade, and accordingly newsbooks and pamphlets used the technique of spoken discourse to communicate with audiences. News culture blurred the lines between the printed and spoken word.40 Though much is now known about the news, print and political cultures of the 1640s, those of the 1650s have received less scholarly attention. As well, the succession of wars during this period have rather separate historiographies. This is of course understandable. At a basic level the Cromwellian conquests of Ireland and Scotland; trade, commerce and the Anglo-Dutch war; and the conquest of Jamaica, the Anglo-Spanish war and the expansion of empire were different types of wars, involved different participants and took place in differ-

Copyright

Selling Cromwells Wars

Copyright

ent geographic regions. Studies that examine this series of wars together tend to approach them from the perspective of high politics, foreign policy and diplomacy. This book in contrast seeks to move the focus from Whitehall and to uncover the ways in which the media as well as politicians promoted, marketed and debated war. Promotion of the various wars of the 1650s shared a common thread: all were framed as godly Protestant wars. Strengthening Protestantism and hindering popery were principal aims of Protestant war. These were mutually dependant goals and constituted two sides of the same struggle: attacking and weakening popery would bolster Protestantism, and bolstering Protestantism would undermine popery. Anti-popery was a key aspect of Protestant, particularly puritan, political and religious culture and played a part in earlier English military and imperial undertakings. Rather than a purely negative construct, anti-popery functioned as a positive mechanism for Protestant advancement.41 Over the course of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries anti-popery had come to form an essential component of public debate.42 Some scholars have contended that the polemical value of anti-popery decreased by the mid-1640s. Following this argument, as various groups of Protestants, including Anglicans, Independents and Presbyterians, labelled one another other as popish during the English civil wars, popery ceased to function as a coherent signifier and a meaningful instrument of social, political and religious critique. Popery became, as one historian has put it, a free-floating term of opprobrium.43 Designating someone or something as popish became a knee-jerk response and habitual form of condemnation.44 In this view, the very ubiquity of anti-popery stripped it of polemical power, rendering it essentially meaningless. For some scholars anti-popery became a purely functional stamp of orthodoxy that can be peeled off and discarded without violating the integrity of the text. From this perspective it is possible, and at times even crucial, to ignore or dispose of anti-popish sentiment to uncover what authors and texts actually meant to say. If we remove what are taken to be perfunctory anti-popish statements from, say, Miltons Areopagitica and Henry Robinsons Liberty of Conscience we can see that Milton and Robinson really may have meant to extend freedom of the press and religious toleration to everyone, including papists.45 These arguments perhaps raise more questions than provide answers. First, by ignoring or discarding portions of a text to bring it more in line with what the author is assumed to have intended, are we not changing what the text says? There is a certain amount of circular thought here. Second, after the Restoration, as historians have noted, anti-popery re-emerged as a potent factor in political culture.46 If it carried meaning before and after the Interregnum, what happened to it in the interim? If it had become meaningless, why did contemporaries persist in employing it and why did propaganda campaigns continue to be built

Introduction

upon it, as Steven Pincus has shown for the first Anglo-Dutch war?47 Examination of other wars during the Commonwealth and Protectorate similarly reveals its ongoing importance. Rather than signifying a loss of meaning, its pervasiveness in contemporary polemic indicates that anti-popery was considered capable of influencing public opinion. By 1649 the Protestant-popish framework had become a convention of public debate and was accessible to men and women of varying political and religious persuasions across the socio-economic spectrum. Its familiarity allowed it to retain currency as a means to contextualize, interpret, promote and challenge the aims, conduct and impact of political policies. In the 1650s debate over the wars of the Commonwealth and Protectorate to a great extent hinged upon whether or not these conflicts were Protestant wars. This is not to suggest that religion, or religious polemic, was the only significant justification or point of debate; indeed it was only one of several, including national security and economic motivations. Yet in contemporary polemic the Protestant-popish framework could accommodate multiple objectives. Since financial, commercial, imperial, territorial and strategic gains for Protestant England implied losses for popish powers, apologists found these goals compatible with Protestant war and empire. This framework also lent an element of continuity to the various wars of the 1650s, though these conflicts took different forms. Focusing on this model allows us to examine the ways in which the media developed, promoted and debated Protestant war in different contexts. For the principles of Protestant war to hold it must be shown both to serve the Protestant interest and target a popish enemy. Proponents, critics and detractors alike generally accepted these term of debate. For example, opponents of the Scottish war, discussed in Chapter 2, maintained that the target was a Protestant (not a popish) enemy and intra-Protestant divisions served popish rather than Protestant interests. Because the war against Spain fought a Catholic enemy, opposition to the Spanish war took different forms. As discussed in Chapter 5, some charged Cromwell with seeking personal rather than Protestant gain, while others held that the Protectorate government itself had become popish and therefore incapable of fighting a Protestant war. Some polemicists interpreted Protestant war from an apocalyptic perspective.48 It has been argued that with the conclusion of the Anglo-Dutch war in April 1654 godly warfare and apocalyptic foreign policy largely disappeared from the political landscape. In this view, Cromwellian moderates gained control and ushered in a new style of foreign policy, one which was founded upon more secular ideas of national interest and reason of state.49 This study demonstrates that Protestant war and apocalypticism survived the Anglo-Dutch war. As can be seen in media promotion of the Western Design and Anglo-Spanish war and in responses to religious

Copyright

10

Selling Cromwells Wars

Copyright

conflict on the continent, apocalypticism and Protestant war continued to shape the Protectorates foreign and imperial aspirations. Chapter 1 focuses on the influence of Protestantism and popery on the development of popular republicanism. The trial and execution of Charles I and the abolition of monarchy were unpopular acts, and from the outset the new republic, established in May 1649, faced potential domestic unrest. Many Commonwealth supporters also feared the possibility of invasion from Ireland and Scotland to overturn the republic and restore Charles II to the throne. In response to these perceived threats the republic launched pre-emptive strikes against Ireland in 1649 and Scotland in 1650. For republican apologists the civil wars of the 1640, fought against a popish king and episcopal church, enabled the emergence of the godly Commonwealth. The new regime was bound to continue this godly struggle to protect the republic from the ongoing danger of monarchy and popery. Promotion of the republic thus took shape in relation to godly warfare. Royalists and Presbyterians challenged the legitimacy of the republic on religious as well as political grounds, and the chapter examines these public debates over republicanism and monarchy. Chapter 2 examines the Cromwellian invasion and conquest of Scotland as a Protestant war. Invading a fellow Protestant nation and former ally against Charles I was controversial.50 The application of the Protestant-popish framework to the war against Presbyterian Scotland highlights its centrality to contemporary news, print and political cultures. While it can be expected in a war against a Catholic nation (and empire, as with Spain), its deployment against a Protestant nation points to its instrumental role in media promotion and policy formation. Like the Dutch war, the invasion and conquest of Scotland required explanation for just how and why Protestants could be construed as popish (without being Catholic). This in turn opened up space for public debate over who and what could be designated as popish and illustrates how that designation influenced the development and marketing of a Protestant war against a Protestant nation. It also affected postwar plans and attitudes towards the defeated. In contrast to the Anglo-Dutch naval war, the Scottish war involved invasion, conquest and ultimately union. In contrast to the Irish war which also saw conquest and union, since Presbyterians were popish but not papists there was hope that Scottish men and women could become reconciled to the godly English republic. Chapter 3 explores Protestant imperialism, the Western Design and conquest of Jamaica. Much of the existing scholarship on the Design focuses upon adversity and defeat: the English armys attempt to capture Santo Domingo failed and the Jamaica settlement struggled for survival. This emphasis has overshadowed the extensive media campaigns publicizing the Design and promoting the Jamaica colony. The chapter also examines ways in which the conduct of

Introduction

11

the Design and conditions at Jamaica influenced media coverage and political policies. The Protectorate government sought to prevent potentially damaging information from becoming public. Tracing the progress of the Design and circulation of information enhances our understanding of greater press controls implemented in the fall of 1655, which took place just as newsbooks began publishing reports on the dismal conditions at Jamaica and the magnitude of the English defeat at Santo Domingo. Chapter 4 takes a broader view of the Anglo-Spanish war on both sides of the Atlantic and examines the efforts to market war and empire in a variety of media. Historical narratives and compilations of Catholic persecution, opera, translations and new editions of previously published works, and polemical pamphlets aimed to mobilize support for the war effort and pursuit of empire. Increased censorship and pro-war propaganda, however, did not silence opposition, and this chapter also explores the public debates surrounding the Anglo-Spanish war. Much of the debate centred upon whether or not the goals and methods of war and expansion of empire were in fact godly and whether or not the current government was equipped to execute them. Chapter 5 focuses on international religious conflict and the English media. Accounts of the massacre of Protestants at Piedmont, the hostility between Protestant and Catholic cantons in Switzerland, the popes efforts to conclude a general Catholic peace and the Swedish-Polish war fostered a sense of an international Protestant unity. In this context the Anglo-Spanish war assumed additional significance. The Protectors war against Spain fit into a larger international Protestant struggle against popery, one with potentially apocalyptic dimensions. The omission of case studies on the conquest of Ireland and first AngloDutch war deserves mention. This should not be taken to suggest that the Irish and Dutch wars are not significant or worthy of study. Several reasons beyond consideration of the books length prompted this decision. One was existing scholarly treatment. The role of anti-popery in the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, particularly in the massacres of Drogheda and Wexford in September 1649, is well known.51 Similarly, Steven Pincus recently has examined the centrality of anti-popery to the Anglo-Dutch war.52 Of course, the existence of previous scholarship on a subject does not mean there is nothing left to say. In contrast to the Irish and Dutch wars, however, the promotion of the Scottish and Spanish conflicts as Protestant wars has received much less sustained attention. In order to explore the ways in which Catholic and Protestant enemies influenced the conceptual deployment of Protestant war this study takes one from each category. As well, focusing on one war from the Commonwealth period and one from the Protectorate enables us to explore media, marketing and public debate in different political and chronological contexts. For these reasons the Scottish and Spanish wars were selected for close examination.

Copyright

Você também pode gostar

- Index To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Documento8 páginasIndex To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Pickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Victorian Medicine and Popular CultureDocumento8 páginasIntroduction To Victorian Medicine and Popular CulturePickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Introduction To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Documento9 páginasIntroduction To Warfare and Tracking in Africa, 1952-1990Pickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945 PDFDocumento3 páginasIntroduction To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945 PDFPickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945 PDFDocumento3 páginasIntroduction To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945 PDFPickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To MalvinaDocumento12 páginasIntroduction To MalvinaPickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Index To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945Documento6 páginasIndex To The Rockefeller Foundation, Public Health and International Diplomacy, 1920-1945Pickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Victorian Literature and The Physics of The ImponderableDocumento17 páginasIntroduction To Victorian Literature and The Physics of The ImponderablePickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Introduction To The Gothic Novel and The StageDocumento22 páginasIntroduction To The Gothic Novel and The StagePickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Adolphe Quetelet, Social Physics and The Average Men of Science, 1796-1874Documento18 páginasIntroduction To Adolphe Quetelet, Social Physics and The Average Men of Science, 1796-1874Pickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830-1910Documento18 páginasIntroduction To Secularism, Islam and Education in India, 1830-1910Pickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To The Early Modern Child in Art and HistoryDocumento20 páginasIntroduction To The Early Modern Child in Art and HistoryPickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Henri Fayol, The ManagerDocumento5 páginasIntroduction To Henri Fayol, The ManagerPickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Scientists' Expertise As PerformanceDocumento13 páginasIntroduction To Scientists' Expertise As PerformancePickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Indulgences After LutherDocumento15 páginasIntroduction To Indulgences After LutherPickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To William Cobbett, Romanticism and The EnlightenmentDocumento17 páginasIntroduction To William Cobbett, Romanticism and The EnlightenmentPickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- History of Medicine, 2015-16Documento16 páginasHistory of Medicine, 2015-16Pickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Chapter 1 From A Cultural Study of Mary and The AnnunciationDocumento15 páginasChapter 1 From A Cultural Study of Mary and The AnnunciationPickering and Chatto100% (1)

- Introduction To The Future of Scientific PracticeDocumento12 páginasIntroduction To The Future of Scientific PracticePickering and ChattoAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Review of Pauline Gregg's King Charles IDocumento3 páginasReview of Pauline Gregg's King Charles IJulian CampbellAinda não há avaliações

- The StuartsDocumento4 páginasThe Stuartsbengrad nabilAinda não há avaliações

- History Gr. 9 HandoutDocumento4 páginasHistory Gr. 9 HandoutAbelAinda não há avaliações

- Bloom S Literary Places Dublin John TomediDocumento214 páginasBloom S Literary Places Dublin John Tomediantigona_brAinda não há avaliações

- Poetry of The Civil War PeriodDocumento18 páginasPoetry of The Civil War PeriodLIVE mayolAinda não há avaliações

- Leadership & Innovation Leadership & Innovation: 300 Years of 300 Years ofDocumento810 páginasLeadership & Innovation Leadership & Innovation: 300 Years of 300 Years ofHomerAinda não há avaliações

- Civilisation Britannique S1Documento18 páginasCivilisation Britannique S1LO PAinda não há avaliações

- The Age of Milton PresentationDocumento15 páginasThe Age of Milton PresentationCecilia KennedyAinda não há avaliações

- English Civil War Cornell NotesDocumento2 páginasEnglish Civil War Cornell Notesapi-327452561Ainda não há avaliações

- Civil War in EnglandDocumento3 páginasCivil War in EnglandsokfAinda não há avaliações

- Has History Been Unfair To Charles I?Documento6 páginasHas History Been Unfair To Charles I?Maliha RiazAinda não há avaliações

- English Revolution and ConstitutionalismDocumento30 páginasEnglish Revolution and Constitutionalismapi-97531232Ainda não há avaliações

- 17th and 18th Century PresDocumento53 páginas17th and 18th Century PresNova SalemAinda não há avaliações

- History - 5 - THE STUARTS - PURITAN REVOLUTIONDocumento14 páginasHistory - 5 - THE STUARTS - PURITAN REVOLUTIONПолина НовикAinda não há avaliações

- Examinations - Ie History Coursework JournalDocumento8 páginasExaminations - Ie History Coursework Journalpudotakinyd2100% (2)

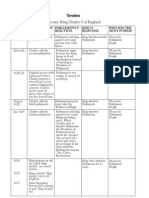

- In 1625, Charles Stuart Became King Charles I of England.: TimelineDocumento2 páginasIn 1625, Charles Stuart Became King Charles I of England.: TimelineNgaire TaylorAinda não há avaliações

- Society in 17Th Century England: A History of English SocietyDocumento14 páginasSociety in 17Th Century England: A History of English SocietyOscar PortilloAinda não há avaliações

- International Human Rights Law and Human Rights Laws in The PhilippinesDocumento28 páginasInternational Human Rights Law and Human Rights Laws in The PhilippinesFrancis OcadoAinda não há avaliações

- Unit 3: Some Important Events in British HistoryDocumento25 páginasUnit 3: Some Important Events in British HistoryLilyAinda não há avaliações

- Monarchy in EnglandDocumento21 páginasMonarchy in Englandterise100% (1)

- The Stuarts, Charles I, The Great FireDocumento8 páginasThe Stuarts, Charles I, The Great FirePopescu LaurAinda não há avaliações

- British History MaterialsDocumento28 páginasBritish History MaterialsIoana MariaAinda não há avaliações

- The Age of AbsolutismDocumento35 páginasThe Age of Absolutismtchic115Ainda não há avaliações

- Elce Notes Unit I - VDocumento37 páginasElce Notes Unit I - VArijith Reddy JAinda não há avaliações

- Wars of The Three Kingdoms - WikipediaDocumento17 páginasWars of The Three Kingdoms - WikipediaJuan JoseAinda não há avaliações

- World History 16.1-16.3 NotesDocumento2 páginasWorld History 16.1-16.3 NotesVictoriaAinda não há avaliações

- 5 5Documento5 páginas5 5api-1954603580% (1)

- C Engleza Scris Model SubiectDocumento4 páginasC Engleza Scris Model SubiectAndreea DeeaAinda não há avaliações

- The Parliamentary Monarchy in EnglandDocumento14 páginasThe Parliamentary Monarchy in EnglandMaria Dolores Lopez RodriguezAinda não há avaliações