Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Reference Document: WOMEN FARMERS: AGENT OF CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT

Enviado por

ffwconferenceDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Reference Document: WOMEN FARMERS: AGENT OF CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT

Enviado por

ffwconferenceDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Reference Document: WOMEN FARMERS CHANGE AND DEVELOPMENT AGENTS

Co-ordinator: ALEXANDRA SPIELDOCH / Gender and Food Systems Consultant. USA

INDEX

1. - Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 2. - Women farmers drivers of development ............................................................................. 2 3. - Women farmers - agents of change ...................................................................................... 6 4. - Specific proposals on gender ................................................................................................ 9 5. - References .......................................................................................................................... 11

1. - Introduction

Women farmers play a vital role in agriculture and natural resource management. The majority of working women in the rural sector are engaged in agriculture some way or another as producers, processors, and laborers. Still, the majority of the worlds rural poor as well as those who are chronically hungry are women. Global trends such as climate change, bioenergy, and price volatility are compounding existing problems women farmers are facing in terms of producing and accessing nutritious food. Policymakers engaged in dialogues on land and investment and price volatility have yet to incorporate the experiences of women farmers as central to their work. While they can benefit from investment and more stable food markets, the reality is that women farmers are vulnerable if their leadership and their concerns are not integrated into the solutions being generated. Unfortunately, while women farmers issues are the subject of many studies and claims, most agricultural programs are not gender sensitive. Moreover, women farmers are absent from most policymaking circles. At the local level, they tend to be poorly organized and their representation in farmers organizations is notably low. In regional and international agriculture and food

security dialogues, aside from rhetoric, they are almost entirely absent. Donors, CSOs, and international organizations are beginning to shift their work internally away from an approach of targeting rural women to recognizing them as agents of change. Leaders from various sectors can and should support concrete strategies for agricultural development that will empower women farmers. The aim of this reference paper is to provide an overview and some recommendations for action.

2. Women farmers drivers of development

Food Production As has been stated, rural women participate in a wide range of agricultural activities: they are farmers on their own account, unpaid workers on their husbands farm, paid or unpaid worker on industrial farms and, last but not least, full-time or part-time farmers. They are involved in both crop and livestock production and fishing. They produce for subsistence and/or for commercialization (FAO 2011). On average, 43% of the agricultural laborers in developing countries are women, with a great regional variability (20% in Latin America and 50% in Eastern Asia and up to 80% in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, respectively). In Europe, women are composing 41% of the agricultural workforce. These figures may be an underestimation due to the fact that women often do not classify their agricultural (and other) activities as work, even if they work more hours than men (ibid., Quintanilla Barba 2011). There are differences in the types of crops that women and men produce. For example, in subSaharan Africa, women are more likely to be producers of food crops for subsistence while men are more engaged in commercial farming for export. In some countries (Burkina Faso, Zambia, Tanzania), women and men grow them together. However, men tend to take over cash crops as they become more profitable. Non-traditional agricultural export production has grown in Africa, and is more female-dominated. This is often accompanied by more precarious working conditions (FAO/IFAD/ILO 2010). For example, in Africa and Latin America, women are involved heavily in non-traditional agricultural export production that is largely defined by seasonal work, low social protection and high exposure to toxic chemical substances (FAO 2011). Women farmers are involved in every step of the food production process, the seed selection and storage and food preparation and commercialization. Apart from that, they are responsible for fetching and carrying water and fuel in order to prepare the meals (UNIFEM 2000, FAO 2008, IAASTD 2009). In times of crisis, women are usually the ones who sacrifice even their

food intake as shown in Cambodia, Indonesia and Timor Leste, thus ensuring the nutrition of their children and partner (Bernabe/Penunia 2009). Unfortunately, women farmers lack control of assets and decision making. In most cases, men decide which crop will be cultivated, how much will be kept for the familys consumption or brought to the market, how much money will be invested in technology, etc. As producers, women are often relegated to the cultivation of secondary crops (legumes, vegetables) and towards more marginal land. They rely on indigenous knowledge and low cost technology and often do not have control over the generated income (Doss 1999, FAO 2002, Spieldoch 2006, IFPRI 2008a, Charmann 2008, IAASTD 2009, IFAD 2010a, ActionAid 2011). Women farmers receive considerably less money than men for the same jobs. They work longer hours and have more of a work burden in light of their roles as unpaid workers and family care providers (FAO 2011). They also expend more time and energy as a result of poor infrastructure than do men. They lack access to resources such as credit, access to markets, rural extension services and technology that could improve their lives substantially (IAASTD 2009, FAO 2011). Ultimately, limited access to resources substantially reduces their ability to invest in seeds, fertilizers, technology or adopt new agricultural techniques (Jiggins 2001, UN 2008, 2008, Weisfeld-Adams 2008, FAO 2011). As a result, women generally produce less than men farmers due to the little input and assistance they receive. By closing the gender gap, women farmers could boost their yields by 20-30%, which could reduce hunger in the world by 12-17 % (FAO 2011). In sub-Saharan Africa, women who received the same inputs as men increased their production of maize, beans and cowpeas by 22% (Caldes/Ahmed 2004). In Kenya, a year of primary school would provide the base for boosting maize production by 24% (IFPRI 2008b). In other areas, such as livestock production and agroforestry, women are also major contributors, but their contributions are hardly counted. For example, although two-thirds of the worlds 600 million poor livestock keepers are rural women, there have been few interventions and research done on their behalf (Kristjanson et al. 2010). Generally, women livestock keepers own smaller animals than men, the former tend to control goats, sheep, pig and poultry, whereas the latter own cattle, horses and camels (FAO 2009). Little reliable data exists on women in forestry. Still, the general numbers suggest that 1.2 billion people in developing countries rely on agroforestry farming systems and managing natural resources. Developing and acting on data to support women, is a key strategy to reducing poverty and promoting sustainable development, including measures to achieve food security (FAO 2011). Women are not only vulnerable but also active protagonists. They respond to challenges such as limited access to land, credit, education, participation and representation. They diversify

agriculture and food production, protect common resources, create employment and associations, research etc. and have the necessary knowledge and skills to do so (Bernabe/Penunia 2009). Access to land The Commission on Human Rights Solution 2000/12 states that women have the right to equal ownership of, access to and control over land and the equal rights to own property and to adequate housing (ECOSOC 1999). Nevertheless, women very often do not have access to land and other natural resources. Although rural women are the main food producers, they own less than 20% of the agricultural land in the world, regardless of the development level. In Western and Central Africa, however, as well as in Near East, this decreased to less than 10% and in North Africa and West Asia, to 5% in the countries for which data are available. In the rest of Asia, numbers are slightly higher (FAO 2010, FAO 2011). In Europe, there are still discriminatory practices persisting (Quintanilla Barba 2011). Migration, armed conflicts, diseases and other social factors have increased the ratio of womenheaded households in the rural sector. Women-headed farms are at increased risk of poverty compared to men-headed farms (Spieldoch 2006, IAASTD 2009, FAO/IFAD/ILO 2010, IFAD 2010a). In Zambia for example, approximately one-fifth of all farms are now headed by women (Action Aid 2011). In most cases, due to legal or de facto customary gender discrimination, they are farming land they do not own. In Kenya, mens landholdings are at average three times bigger, whereas in Bangladesh, Ecuador and Pakistan, they are two times the size of womens landholdings (Deere/Doss 2006, FAO 2011). In Northern countries, the gendered difference in farm size is usually considerable as well (Farnworth/Hutchings 2009, Bundeskanzleramt sterreich 2010). Lack of access to land also hinders womens access to credit, and therefore their ability to benefit from new markets, which would provide sources of income and strategies for empowerment. For example, in Africa, women farmers received less than 10% of the credits that were given to men. In Bangladesh, women received slightly more than 5% of the loans disbursed in rural areas in 1990 and even if they received the money, they invested in male activities. In Eastern Asia, in general, there coexist different realities: in China, women seem to have the same access to land and credit as men, whereas in Vietnam, women have less access to land, credit and they have to pay higher interests (IAASTD 2009, FAO/IFAD/ILO 2010, FAO 2011). Both land and credit are crucial in order to create self-employment (Ghosh 2009, FAO/IFAD/ILO 2009). Moreover, the improvement of womens direct access to financial resources ameliorates the investment in childrens health, nutrition and education as well (FAO 2011).

In cases of widowhood, divorce or migration, women farmers regularly lose their entitlements, greatly increasing their physical risk and their potential to live in poverty. Strengthening womens access to land will improve their social recognition in their communities and has direct influence on productivity and households welfare (IFPRI 2008a, IAASTD 2009, FAO 2010, FAO 2011, Kumar/Quisumbing 2011). As to livestock, the same general rule applies: male-headed households have larger livestock than female-headed. In Bangladesh, Ghana and Nigeria, male holdings are three times bigger than those of female farmers (FAO 2011).

Information and Decision-Making Power Education is a major area of discrimination against women in the rural sector. Over two-thirds of the worlds illiterate people are women, many living in rural areas. Women farmers are also less likely to receive a general education. Due to the high percentage of illiterate rural women farmers, women hardly participate in agricultural and other training activities. Nevertheless, even if women reach a certain educational level, agricultural research is dominated by male personnel, both in the North and in the South (IAASTD 2009, Farnworth/Hutchings 2009, FAO 2011). In some Southern countries such as Botswana, Nigeria, Senegal, however, the female staff increased notably to 50% (between 2000/01 and 2007/08) (FAO 2011). In spite of their lack of formal education, they are custodians of ecosystems, soil, water and seed conservation as well as more traditional farming techniques (IAASTD 2009, FAO 2011). They are involved in the whole range of natural and genetic conservation tasks that are part of the whole crop cycle (from seed selection to planting, harvesting, storage and processing), know about local adapted and nutritious varieties and have much to share in terms of educating others (Tapia/de la Torre 1998, Doss 1999, ILEIA 2011). They would benefit immensely from exchanging and learning techniques that reduce their time burden (time poverty) and help them to adapt to external shocks resulting from climatic, economic or social crisis (IAASTD 2009, FAO/IFAD/ILO 2010). Women are also poorly represented in decision-making processes in the rural sector. They lack a formal voice in rural and farmers organizations, research institutes and governmental services (Charmann 2008, IAASTD 2009, Quintanilla Barba 2011). They often face threats and violence when they do seek to take on more leadership (IFAD 2010a). When they participate in mixed producer group dialogues, they are often silent (Meinzen-Dick et al. 2010). In certain cases, although they are doing the majority of the farming, they do not even refer to themselves as farmers. Rather, they are helping out their husbands in the fields (FAO 2011). It is essential that women farmers are more recognized as leaders who bring a wealth of knowledge, expertise and skill relating to agriculture and natural resource management. They are also generally more knowledgeable about the mix of social issues connected to food production and

provision because with their income and time, they take care of the young and elderly, provide education, ensure that food is on the table and provide healthcare for their families (IAASTD 2009).

3. Women as Agents of Change

Women want to influence the decisions that affect the lives of their families and communities, as well as their political and economic environments. In order to hold their representatives and governments accountable, women want to be better-informed, and to have their own information, experiences and ideas valued and organized into voices for change The culture of silence where women will accept the decisions of male heads of household and male leaders, even if those decisions might have negative implications for them, will wear down as women build their own support networks. (Tandon 2010:509) The World Conference on Human Rights in 1993 underlined the importance of women as both agents and beneficiaries in the development process rather than simply as victims. This is an important distinction to make, one that should be guiding global policymaking and programming. Assuming there is consensus to recognize women farmers as beneficiaries and agents of change, their empowerment in this process cannot be over-emphasized. There are some international commitments that have been made already by governments (World Conference on Human Rights 1993). The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), 1979, Article 14, commits governments to eliminating discrimination against women in rural areas so that they can participate and benefit from rural development. This includes womens participation in planning, their access to health, education and training, their ability to organize self-help groups and co-operatives and to have access to agricultural credit and loans, technology and equal treatment in land and agrarian reform and land resettlement (CEDAW 1979). The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BDPfA), 1995, also refers to rural women in Critical Area F on Women and the Economy commits governments to implement programs that support rural womens employment, their access to credit and capital, improving their income as well as their control over resources, and institutional reform to increase technical assistance in rural communities, and policies that strengthen rural womens role in food security (BDPfA 1995). The Final Declaration of the Convention on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ICARRD) from Porto Alegre in 2006 affirms global support for rural womens land rights and rural peoples livelihoods. Governments commit to dialogues, laws and policies to respect and include women leaders as well as womens rights (ICARRD 2006).

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights, on the Rights of Women in Africa, 2003, refers to womens rights with regard to food security (including access to clean water and systems of storage and supply), natural resource management (including greater participation of women in planning, management and preservation of the environment, appropriate technologies for women, respect for indigenous knowledge systems, sustainable development (including gender mainstreaming into development policies and programs, women access to credit, training, and extension, and making sure that macroeconomic policies and programs do not have a negative effect on women in their implementation). Article 21 also refers to the need to give women widows the right to inheritance (ACHPR 2003). Another important step towards gender equality would be the fulfillment of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG). Regarding the prevailing discrimination against women, the MDG state that the gender gap in education, employment, health, nutrition, access to resources and services, autonomy, participation and leadership, in short: opportunities, should be substantially reduced until 2015. Up to now, however, results have been mixed (UN 2010). From these international commitments, there are examples, albeit only a few, in which government commitment to gender is contributing to improving the lives of women farmers. For instance, Tunisia and Zambia have adopted inheritance laws for women. In Zambia, the government has also instituted programs to provide women land inheritance rights (Charmann 2008, IFAD 2010a). In MERCOSUR, the Working Group on Gender as part of REAF, the Specialized Meeting on Family Farmers, has been instituted. As a result, gender issues are now raised during official discussions on land titles, credits etc. for family farmers (Foti 2009, FRM/PROCISUR 2010). A few Latin American countries (Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Honduras and Nicaragua) also passed agrarian legislation in the 1990s that include women in land titles along with their spouses. Similar laws have been passed in Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Laos, Vietnam and other Asian countries. In Philippines, certificates of land ownership awards granted under the governments agrarian reform program can be in the name of both the husband and the wife. In the European countries, shared land tenure rights are still not guaranteed in all the member countries (UN-HABITAT 2005, FAO/IFAD/ILO 2010). It would be misleading to imply that these changes have been groundbreaking as the results in terms of gender equality have been mixed (ibid.). Still, they are important steps toward empowering women farmers and toward reversing gender discrimination in agriculture and natural resource management. Of course, more support is needed to promote rural women as agents of change. This includes financial and political support for more womens organizations and more womens leadership in farmer organizations that lack gender sensitivity. In 2010, IFAD organized a global farmers forum at which a separate day was planned only for women producers and womens organizations. The women released a statement calling on

governments to include women farmer leaders in country and global policy processes and in the design of the projects and programs, establish quotas for participation, and increase the capacity of farmers organizations to address gender issues (IFAD 2010b).

Women and climate change in Asia Asian farmers are severely hit by unpredictable climatic phenomena. Of them, Asian women farmers have less possibility to adapt to climate change and its consequences, since they are the poorest and depend heavily on their crop. Floods and droughts and especially their unpredictability are posing a severe challenge to women farmers, as well as increasing scarcity of natural resources. Womens traditional role as food provider for the family puts them in a difficult situation: they cannot guarantee the food security or sovereignty of their families any longer and have to assume the consequences through compensatory activities or migration, which increments their workload, augments domestic violence and contributes to a reduction of their food intake, health condition etc. On the other hand, they are active stakeholders responding to these difficulties. For instance, they diversify their crops and protect common resources such as watershed systems and forests. (Bernabe/Penunia 2009).

In general, women have a huge capacity of resilience : they organize themselves in order to anticipate difficulties, reduce the impact of adverse circumstances and cope with and recover from them. Resilience implies the protection of pivotal resources, innovation and development of new strategies, in short: general abilities of adaptation. For women, networking, the diversification of strategies, the employment of traditional knowledge and the exploitation of their bargaining and decision-making power are crucial. Poor women in general and women farmers in particular are highly experienced in resilience. Therefore, participatory programs and projects which are identified and implemented by the women themselves are an excellent instrument to strengthen their protagonism and empower them to fully exploit their capacity as agents (GROOTS/UNDP 2011). Various initiatives in agriculture being led by women need to be replicated. For example, the Self-employed Womens Association (SEWA) is a country-wide network of cooperatives, selfhelp groups (SHGs), banks and training centers that help address the multiple constraints that women face. Its membership includes 1.3 million women and 54 percent of its members are small and marginal farmers based in rural areas. In another example, the Food and Natural

Resilienceisthecapacityofpositivelycopingwithstressandadversity,whichcanbedevelopedat individualorgrouplevel.

Resources Policy Analysis Networks (FANRPAN) Women Accessing Realigned Markets (WARM) project recently launched a series of Theatre for Policy Advocacy (TPA) campaigns in rural Malawi. Working with its Malawi-based partners, FANRPAN had the first community performances in October 2010 in Sokelele Village in Lilongwe District. Through theater, womens stories and challenges are being captured so as to improve better agricultural policy. Tamil Womens Collective in India is focused on water harvesting techniques, promotion of multi-functionality in agriculture, growing indigenous crop varieties, supporting natural food production without chemicals, and strengthening local food systems. In South Korea, the Women Advanced Farmers Federation was established in 1996. It is a federation of 70,000 women farmers and provides education services, organizes exchange between city and farm villages, upholds the protection of farmers rights, cooperates with other farmers organizations, advocates for good agricultural policies and administers the needs of its members. It gathers around seven to eight thousand members every two years in one of South Koreas biggest womens convention that aims to improve women farmers rights and interests (www.sewa.org, www.fanrpan.org, www.womenscollective.net, www.asianfarmers.org).

4. - Specific Recommendations to Decision Makers and CSOs

End gender discrimination Incorporate gender in key aspects of (participatory) policymaking: implementation, monitoring and evaluation this requires budgetary support. design,

Eliminate gender discrimination in the national legislation (especially regarding land and livestock tenure, access to resources and contractual rights), taking into account the discrepancy between constitutional and customary law and the accessibility of related facilities. Strengthen awareness among women regarding their rights, especially rural women farmers. Recognize womens role aside from being food producers - as agents of development and change. Prioritize gender disaggregated data to identify gaps and needs for policy and program. Strengthen rural and local institutions abilities to become more gender sensitive in their analysis and programming. Incorporate men in the gender strategies in order to change power structures.

Invest in women farmers Develop more effective partnership with multi-stakeholders (governments, private sector, academics, producers, NGOs) to increase support for women farmers and their grass-root associations. Provide gender-sensitive credit and saving systems that support women farmers. Target investment to enhance womens knowledge, training, innovation, & capacity building for decision-making, after having listened to womens special needs and aspirations. Put special emphasis on their approaches towards sustainable development. Provide educational support for girls and women through training facilities, scholarships, extension services and other forms of technical assistance. Increase the number of women extension agents and train male extension agents to become more gender sensitive. Prioritize womens access to ICT. Strengthen investments that enhance womens roles and capacities to undertake projects that link agriculture, nutrition and health.

Promote womens leadership Facilitate rural womens participation in all relevant decision-making processes (all levels) through mandatory quotas, leadership training, information sharing and visibility. Encourage and support associations of rural women in order to defend their practical and strategic interests. Support womens cooperatives and their participation in mixed cooperatives. Provide multi-purpose spaces for meetings, activities of the organization and cooperatives etc. Invest in women scientists and gender-based research in agriculture and rural development sector in developing countries. Engage grassroots women as advisors and informers on pertinent issues that relate to their rights. Developing action research that directly involves and allows for contributions of the local communities. Promote women champions who will advocate for womens rights at the highest levels in governments departments. Capture womens success stories that can serve to inspire other women in similar circumstances. Conduct formation and gender-based leadership programs employing various methodologies that include farmers exchange visits, study tours, learning and reflection sessions.

10

5. - References

ACHPR (2003): Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa, Maputo 11 July 2033, in: http://www.achpr.org/english/women/ protocolwomen.pdf (access: 08/08/2011). ActionAid (2011): Making CAADP working for women farmers. A review of progress in six countries, ActionAid: Johannesburg. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995): The Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing 4-15 September 1995, in: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/BDPfA% 20E.pdf (access: 08/08/2011). Bernabe, Mara Dolores/Penunia, Estrella (2009): Gender links in agriculture and climate change, Isis International: Manila. Bundeskanzleramt sterreich (2010): Frauenbericht 2010, Teil 1: Statistische Analysen zur Entwicklung der Situation von Frauen in sterreich. Kapitel 6: Frauen im lndlichen Raum, Bundeskanzleramt: Wien. Caldes, Natalia/Ahmed, Akhter U. (2004): Food for Education: A review of Program Impacts, June 2004, IFPRI: Washington D.C. Charmann, A. J. E. (2008): Empowering women through livelihoods orientated agricultural service provision. A consideration of evidence from Southern Africa, Research Paper N 2008/01, United Nations University, UN-WIDER: Helsinki. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) (1979), http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/cedaw.htm (access: 08/08/2011). Deere, Carmen Diana/Doss, Cheryl R. (2006): Gender and the distribution of wealth in developing countries, Research Paper N 2006/115, UN WIDER: Helsinki. Doss, Cheryl R. (1999): Twenty-five years of research on women farmers in Africa: Lessons and implications for agricultural research institutions, CIMMYT Economics Program Paper N 99-02, CIMMYT: Mexico D.F. ECOSOC (2007): Strengthening efforts to eradicate poverty and hunger, including through the global partnership for development, report of the Secretary-General, substantive session of 2007, Geneva, 2-27 July 2007. ECOSOC (1999): Resolution E/CN.4/2000/12, 28th December 1999, UN Commission on Human Rights: Geneva. FAO (2011): State of Food and Agriculture (SOFA) 2011: Women and agriculture: Closing the gender gap for development, FAO: Rome. FAO (2010): Gender and land rights, Policy Brief 8, March 2010, FAO: Rome. FAO (2009): The State of Food and Agriculture (SOFA) 2009: Livestock in the balance, FAO: Rome. FAO (2008): Climate change, biofuels and land, fact sheet, FAO: Rome. FAO (2002): Women, agriculture and Food Security, fact sheet, FAO: Rome. FAO/IFAD/ILO (2010): Gender dimensions of agricultural and rural employment: Differentiated pathways out of poverty. Status, trends and gaps, FAO/IFAD/ILO: Rome.

11

Farnworth, Cathy/Hutchings, Jessica (2009): Organic agriculture and womens empowerment, IFOAM: Bonn. Foti, Mara del Pilar (2009): Mujeres en la Agricultura Familiar del MERCOSUR. Organizacin e incidencia poltica, Red Internacional de Gnero y Comercio, Montevideo. FRM/PROCISUR (2010): Alimentar al mundo, cuidar el planeta. Encuentro continental de Amrica, Foro Rural Mundial/Ministerio de desarrollo agrario Brasil/COPROFAM/ PROCISUR/REAF, 13-14 de noviembre de 2010, Brasilia, Brasil. Ghosh, Jayati (2009): The impact of the crisis on women in developing Asia. The crisis impact on womens rights: sub-regional perspectives, AWID Brief 3, AWID: Toronto. GROOTS/UNDP (2011): Leading resilient development. Grassroots womens priorities, practices and innovations, GROOTS/UNDP: New York. IAASTD (2009): Agriculture at a crossroads. Global report, IAASTD: Washington D.C. ICARRD (2006): International Conference on Agrarian Reform and Rural Development Final report, Porto Alegre 7-10 March 2006, in: http://www.icarrd.org/sito.html (access: 08/08/2011). IFAD (2010a): Rural Poverty Report. New realities, new challenges: new opportunities for tomorrows generation, Rome. IFAD (2010b): Report of the third global meeting of The Farmers Forum, IFAD: Roma. IFPRI (2008a): Nutrition and gender in Asia: From research to action, Washington D.C., http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/NutritionGenderbro.pdf (access: 08/08/2011). IFPRI (2008b): Women: The key to Food Security, Washington D.C., http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/pubs/pubs/ib/ib3.pdf (access: 08/08/2011). ILEIA (2011): Labour and energy in small-scale farming, Module 5, Learning AgriCultures Series, ILEIA: Amersfoort. Jiggins, Janet et al. (2001): Improving women farmers access to extension services, FAO: Rome Kristjanson, Patti et al. (2010): Livestock and Womens livelihoods. A review of recent evidence, Discussion Paper N 20, International Livestock Research Institute: Addis Ababa. Kumar, Neha/Quisumbing, Agnes R. (2011): Gendered impact of the 2007-2008 Food Price Crisis. Evidence using panel data from rural Ethiopia, IFPRI Discussion Paper 01093, June 2011, IFPRI: Washington D.C. Meinzen-Dick, Ruth/Quisumbing, Agnes/Behrmann, Julia/Biermayr-Jenzano, Patricia/Wilde, Vick/Noordeloos, Marco/Ragasa, Catherine/Beintema, Nienke (2010): Engendering agricultural research, IFPRI Discussion Paper N 973, IFPRI: Washington D.C. Ogalleh, Sarah Ayeri (2011): WOCAN Report from Pan African Conference on Land Rights and Justice for African Women in: http://www.wocan.org/news/story/wocan-report-frompan-african-conference-on-land-rights-and-justice-for-african-women-may-30thjune (access: 08/08/2011). Quintanilla Barba, Carmen (2011): Rural women in Europe, Doc 12460, Parliamentary Assembly of the European Council, Committee on equal opportunities for women and men, Council of Europe: Strasbourg.

12

Quisumbing, Agnes/Pandolfelli, Lauren (2008): Promising approaches to address the needs of poor female farmers, IFPRI Note 13, IFPRI: Washington D.C. Spieldoch, Alexandra (2006): A Row to Hoe: The Gender Impact of Trade Liberalization on our Food System, Agricultural Markets and Womens Human Rights. Friedrich-EbertStiftung: Geneva. Tandon, Nidhi (2010): New Agribusiness Investments Mean Wholesale Sell-Out for Women Farmers, in: Gender and Development, Vol. 18, N 3, November 2010, pp. 503514. Tapia, Mara E./de la Torre, Ana (1998): Women farmers and Andean seeds, IPGRI: Rome. UN (2008): Women Farmers: The invisible producers, http://www.un.org/ecosocdev/geninfo/ afrec/vol11no2/women.htm (access: 08/08/2011). UN (2010): The Millennium Development Goals Report 2010, UN: New York. UNDP Mexico (2008): Gua de recursos de gnero para el cambio climtico, UN Development Programme Mexico, UNDP: Mexico D.F. UN-HABITAT (2005): Shared tenure options for women. A global overview, UN-HABITAT: Nairobi. UNIFEM (2000): Progress of the worlds women, UN Development Fund for Women, UNIFEM: New York. Weisfeld-Adams, Emma (2008): Women farmers and Food Security, Fact sheet, The Hunger Project: New York. World Conference on Human Rights (1993): Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, Vienna 25 June 1993, in: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/pdf/vienna.pdf (access: 08/08/2011).

13

Você também pode gostar

- Report On Working Groups: Women Farmers Agent of Change and DevelopmentDocumento12 páginasReport On Working Groups: Women Farmers Agent of Change and DevelopmentffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Agricultural Policies To Promote Family Farming: Shivaji Pandey Director Plant Production and Protection Division FAODocumento14 páginasAgricultural Policies To Promote Family Farming: Shivaji Pandey Director Plant Production and Protection Division FAOffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Dr. V. V. SADAMATE. Advisor of The Planning Commission of India. Indian Government.Documento15 páginasDr. V. V. SADAMATE. Advisor of The Planning Commission of India. Indian Government.ffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- AGUSDIN PULUNGAN. President of WAMTI (Indonesian Farmers Society) - Indonesia. AsiaDocumento4 páginasAGUSDIN PULUNGAN. President of WAMTI (Indonesian Farmers Society) - Indonesia. AsiaffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

- Mr. BASAVARAJ INGIN. CIFA (Consortium of Indian Farmers Associations) - India.Documento4 páginasMr. BASAVARAJ INGIN. CIFA (Consortium of Indian Farmers Associations) - India.ffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Mr. PHILLIP KIRIRO. President Eastern African Farmers' Federation (EAFF) .Documento6 páginasMr. PHILLIP KIRIRO. President Eastern African Farmers' Federation (EAFF) .ffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Antonis CONSTANTINOUDocumento6 páginasAntonis CONSTANTINOUffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Esther PenuniaDocumento5 páginasEsther PenuniaffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Joris BAECKEDocumento11 páginasJoris BAECKEffwconferenceAinda não há avaliações

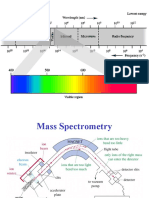

- Mass SpectrometryDocumento49 páginasMass SpectrometryUbaid ShabirAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Mobil Delvac 1 ESP 5W-40Documento3 páginasMobil Delvac 1 ESP 5W-40RachitAinda não há avaliações

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Full Bridge Phase Shift ConverterDocumento21 páginasFull Bridge Phase Shift ConverterMukul ChoudhuryAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- SM FBD 70Documento72 páginasSM FBD 70LebahMadu100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Consent CertificateDocumento5 páginasConsent Certificatedhanu2399Ainda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- 1 Nitanshi Singh Full WorkDocumento9 páginas1 Nitanshi Singh Full WorkNitanshi SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Pet 402Documento1 páginaPet 402quoctuanAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Certification "Products Made of Compostable Materials" Procedure No. 3355757Documento3 páginasCertification "Products Made of Compostable Materials" Procedure No. 3355757Rei BymsAinda não há avaliações

- Fittings: Fitting Buying GuideDocumento2 páginasFittings: Fitting Buying GuideAaron FonsecaAinda não há avaliações

- SET 2022 Gstr1Documento1 páginaSET 2022 Gstr1birpal singhAinda não há avaliações

- MAIZEDocumento27 páginasMAIZEDr Annie SheronAinda não há avaliações

- E3sconf 2F20187307002Documento4 páginasE3sconf 2F20187307002Nguyễn Thành VinhAinda não há avaliações

- OpenStax - Psychology - CH15 PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERSDocumento42 páginasOpenStax - Psychology - CH15 PSYCHOLOGICAL DISORDERSAngelaAinda não há avaliações

- Sargent Catalog CutsDocumento60 páginasSargent Catalog CutssmroboAinda não há avaliações

- DELIGHT Official e BookDocumento418 páginasDELIGHT Official e BookIsis Jade100% (3)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- CampingDocumento25 páginasCampingChristine May SusanaAinda não há avaliações

- Indiana Administrative CodeDocumento176 páginasIndiana Administrative CodeMd Mamunur RashidAinda não há avaliações

- Recommendation On The Acquisation of VitasoyDocumento8 páginasRecommendation On The Acquisation of Vitasoyapi-237162505Ainda não há avaliações

- Gmail - RedBus Ticket - TN7R20093672Documento2 páginasGmail - RedBus Ticket - TN7R20093672Bappa RoyAinda não há avaliações

- Just Another RantDocumento6 páginasJust Another RantJuan Manuel VargasAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- BARCODESDocumento7 páginasBARCODESChitPerRhosAinda não há avaliações

- Equine Anesthesia Course NotesDocumento15 páginasEquine Anesthesia Course NotesSam Bot100% (1)

- Compensation ManagementDocumento2 páginasCompensation Managementshreekumar_scdlAinda não há avaliações

- Grundfos Data Booklet MMSrewindablesubmersiblemotorsandaccessoriesDocumento52 páginasGrundfos Data Booklet MMSrewindablesubmersiblemotorsandaccessoriesRashida MajeedAinda não há avaliações

- FINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Documento67 páginasFINALE Final Chapter1 PhoebeKatesMDelicanaPR-IIeditedphoebe 1Jane ParkAinda não há avaliações

- KhanIzh - FGI Life - Offer Letter - V1 - Signed - 20220113154558Documento6 páginasKhanIzh - FGI Life - Offer Letter - V1 - Signed - 20220113154558Izharul HaqueAinda não há avaliações

- Durock Cement Board System Guide en SA932Documento12 páginasDurock Cement Board System Guide en SA932Ko PhyoAinda não há avaliações

- PaintballDocumento44 páginasPaintballGmsnm Usp MpAinda não há avaliações

- Mapeh 9 Aho Q2W1Documento8 páginasMapeh 9 Aho Q2W1Trisha Joy Paine TabucolAinda não há avaliações

- Open Cholecystectomy ReportDocumento7 páginasOpen Cholecystectomy ReportjosephcloudAinda não há avaliações