Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

OECD Economic Outlook 90

Enviado por

ABC News OnlineDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

OECD Economic Outlook 90

Enviado por

ABC News OnlineDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK

PRELIMINARY VERSION

90

NOVEMBER 2011

The OECD Economic Outlook is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The assessments given of countries prospects do not necessarily correspond to those of the national authorities concerned. The OECD is the source of statistical material contained in tables and figures, except where other sources are explicitly cited. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area.

Please cite this publication as: OECD (2011), OECD Economic Outlook, Vol. 2011/2, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2011-2-en

ISBN 978-92-64-09249-5 (print) ISBN 978-92-64-09436-9 (PDF)

Series: OECD Economic Outlook ISSN 0474-5574 (print) ISSN 1609-7408 (online)

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Corrigenda to OECD publications may be found on line at: www.oecd.org/publishing/corrigenda.

OECD 2011

You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgment of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to rights@oecd.org. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at info@copyright.com or the Centre franais dexploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at contact@cfcopies.com.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Editorial: The Policy Imperative: Rebuild Confidence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Chapter 1. General Assessment of the Macroeconomic Situation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Summary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Key forces acting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The muddling-through projection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Policies in the muddling-through projection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Alternative scenarios for the euro area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Alternative fiscal policy scenarios for the United States. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The OECD Strategic Response to an economic relapse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Chapter 2. Developments in Individual OECD Countries . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . United States . . . . . . . . . . . Japan . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Euro Area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Germany . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . France . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Italy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . United Kingdom. . . . . . . . . Canada . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Australia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Austria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Belgium . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Chile. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70 75 80 85 90 95 99 104 109 112 115 118 Czech Republic . . . . . . . . . Denmark . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Estonia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Finland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Greece. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Hungary . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Iceland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ireland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Israel. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Korea . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Luxembourg . . . . . . . . . . . Mexico . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121 124 127 130 133 136 139 142 145 148 151 154 Netherlands . . . . . . . . . . . . New Zealand . . . . . . . . . . . Norway . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Poland . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Portugal. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Slovak Republic . . . . . . . . . Slovenia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Spain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Sweden . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Switzerland . . . . . . . . . . . . Turkey. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 9 10 11 12 20 32 39 61 63 69 157 160 163 166 169 172 175 178 181 184 187

Chapter 3. Developments in Selected Non-member Economies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Brazil . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 192 China . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 196 India . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Indonesia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200 204 Russian Federation . . . . . . South Africa . . . . . . . . . . . .

191 207 211 215

Statistical annex . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Boxes 1.1. Risk awareness, uncertainty and confidence. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.2. Policy and other assumptions underlying the projections . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.3. The anchoring of inflation expectations and the risk of deflation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.4. The decisions taken at the October 2011 Euro summit and EU Council meeting. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.5. Calibrating a stylised downside scenario in the euro area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.6. Calibrating a stylised upside scenario in the euro area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18 20 24 37 49 57

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Tables 1.1. The global recovery has lost momentum . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.2. 1.3. 1.4. 1.5. 1.6. 1.7. 1.8. 1.9. 1.10. OECD labour market conditions are no longer improving . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . World trade is slowing and imbalances remain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Fiscal positions will improve only slowly. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bank exposure to Greek sovereign and total debt. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . EU / IMF Programme countries : Funding needs and sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Stress-tested banks exposures to Belgian, Italian and Spanish debt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . US and Japanese banks: Exposure to programme and vulnerable euro countries . . . . . . . . . . . . . The impact of stronger US fiscal consolidation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The combined impact of stronger US fiscal consolidation and a stylised euro area downside scenario . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

11 27 30 35 43 44 47 48 62 63 13 15 16 16 17 23 26 28 29 35 44 46 55 60 64

Figures 1.1. Business surveys point to a much weaker outlook . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Equity markets have weakened again . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . It has become more expensive to insure unsecured bank debt against default. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Investors are now discriminating strongly across euro area sovereign bonds. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Overall financial conditions have been hit in the euro area . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Global growth is heavily dependent on the non-OECD economies . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Underlying inflation is likely to moderate . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Considerable labour market slack is set to persist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Global imbalances remain elevated . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The composition of fiscal consolidation plans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Official loans to the governments of Greece, Ireland and Portugal . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Belgium, Italy and Spain: the impact of higher interest rates on consolidation needs. . . . . . . . . Belgium, Italy, Spain and euro area programme countries: bond-market size, government funding needs and banks holding of sovereign bonds . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.14. The evolution of intra-euro area unit labour costs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.15. The size of the automatic fiscal stabilisers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.2. 1.3. 1.4. 1.5. 1.6. 1.7. 1.8. 1.9. 1.10. 1.11. 1.12. 1.13.

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

TABLE OF CONTENTS

This book has...

A service that delivers Excel les from the printed page!

StatLinks2

Look for the StatLinks at the bottom right-hand corner of the tables or graphs in this book. To download the matching Excel spreadsheet, just type the link into your Internet browser, starting with the http://dx.doi.org prefix. If youre reading the PDF e-book edition, and your PC is connected to the Internet, simply click on the link. Youll find StatLinks appearing in more OECD books.

Conventional signs

$ mb/d .. 0 US dollar Japanese yen Pound sterling Euro Million barrels per day Data not available Nil or negligible Irrelevant . I, II Q1, Q4 Billion Trillion s.a.a.r. n.s.a. Decimal point Calendar half-years Calendar quarters Thousand million Thousand billion Seasonally adjusted at annual rates Not seasonally adjusted

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

EDITORIAL:THE POLICY IMPERATIVE: REBUILD CONFIDENCE

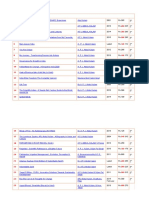

Summary of projections

2011 2011 2012 2013 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q4 / Q4 Per cent 2012 2013 2011 2012 2013

Real GDP growth United States Euro area Japan Total OECD Inflation1 United States Euro area Japan Total OECD Unemployment rate2 United States Euro area Japan Total OECD World trade growth Current account balance3 United States Euro area Japan Total OECD Fiscal balance3 United States Euro area Japan Total OECD Short-term interest rate United States Euro area Japan

1.7 1.6 -0.3 1.9 2.5 2.6 -0.3 2.5

2.0 0.2 2.0 1.6 1.9 1.6 -0.6 1.9

2.5 1.4 1.6 2.3 1.4 1.2 -0.3 1.5

2.0 0.7 6.0 2.4 2.9 2.7 0.2 2.8

2.5 -1.0 1.5 1.1 2.9 2.5 -0.3 2.6

1.7 -0.4 1.8 1.2 2.4 2.0 -0.6 2.2

1.9 0.5 1.8 1.7 2.0 1.6 -0.5 1.9

2.2 1.1 1.6 2.2 1.8 1.6 -0.6 1.8

2.3 1.3 1.5 2.1 1.6 1.4 -0.6 1.7

2.5 1.5 1.5 2.3 1.5 1.3 -0.5 1.6

2.7 1.6 1.6 2.4 1.4 1.2 -0.4 1.6

2.8 1.7 1.7 2.7 1.3 1.2 -0.3 1.5

2.8 1.8 1.8 2.5 1.2 1.2 -0.2 1.5

1.5 0.9 0.8 1.6

2.0 0.6 1.7 1.8

2.7 1.7 1.6 2.5

year-on-year

9.0 9.9 4.6 8.0 6.7 -3.0 0.1 2.2 -0.6 -10.0 -4.0 -8.9 -6.6 0.4 04 1.4 0.2

8.9 10.3 4.5 8.1 4.8 -2.9 0.6 2.2 -0.4 -9.3 -2.9 -8.9 -5.9 0.4 04 1.0 0.2

8.6 10.3 4.4 7.9 7.1 -3.2 1.0 2.4 -0.4 -8.3 -1.9 -9.5 -5.1 0.3 03 0.6 0.2

9.1 10.0 4.4 8.0 5.8

9.0 10.1 4.5 8.1 3.5

9.0 10.2 4.6 8.1 4.2

9.0 10.3 4.5 8.1 5.5

8.9 10.3 4.5 8.1 6.2

8.8 10.4 4.5 8.1 6.8

8.7 10.4 4.4 8.0 7.3

8.6 10.3 4.4 8.0 7.6

8.5 10.2 4.4 7.9 7.8

8.4 10.1 4.4 7.8 8.1 5.1 5.7 7.7

0.3 03 1.6 0.3

0.4 04 1.4 0.3

0.4 04 1.1 0.3

0.4 04 1.0 0.3

0.4 04 0.9 0.2

0.3 03 0.8 0.2

0.3 03 0.7 0.2

0.2 02 0.6 0.2

0.3 03 0.5 0.2

0.4 04 0.4 0.2

Note: Real GDP growth and world trade growth (the arithmetic average of world merchandise import and export volumes) are seasonally and working-day adjusted annualised rates. Inflation is measured by the increase in the consumer price index or private consumption deflator for the United States and total OECD. The "fourth quarter" columns are expressed in year-on-year growth rates where appropriate and in levels otherwise. Interest rates are for the United States: 3-month eurodollar deposit; Japan: 3-month certificate of deposits; euro area: 3-month interbank rate. The cut-off date for information used in the compilation of the projections is 22 November 2011. 1. USA; price index for personal consumption expenditure, Japan; consumer price index and the euro area; harmonised index of consumer prices. 2. Per cent of the labour force. 3. Per cent of GDP. Source: OECD Economic Outlook 90 database.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932541607

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

EDITORIAL: THE POLICY IMPERATIVE: REBUILD CONFIDENCE

EDITORIAL: THE POLICY IMPERATIVE: REBUILD CONFIDENCE

he global economy has deteriorated significantly since our previous Economic Outlook. Advanced economies are slowing down and the euro area appears to be in a mild recession. Concerns about sovereign debt sustainability in the European monetary union are becoming increasingly widespread. Recent contagion to countries thought to have relatively solid public finances could massively escalate economic disruption if not addressed. Unemployment remains very high in many OECD economies and, ominously, long-term unemployment is becoming increasingly common. Emerging economies are still growing at a healthy pace, but their growth rates are also moderating. In these countries falls in commodity prices and the slower global growth have started to mitigate inflationary pressures. More recently, international trade growth has weakened significantly. Contrary to what was expected earlier this year, the global economy is not out of the woods. Many factors underpin this assessment. The headwinds of deleveraging in the financial and government sectors remain with us. Likewise, imbalances within the euro area, which reflect deep-seated fiscal, financial and structural problems, have not been adequately resolved. Above all, confidence has dropped sharply as scepticism has grown that euro area policy makers can deal effectively with the key challenges they face. Serious downside risks remain in the euro area, linked to the possibility of a sovereign default and its cross-border effects on creditors, and loss of confidence in sovereign debt markets and the monetary union itself. Another serious downside risk is that no action will be agreed upon to counter the pre-programmed fiscal tightening in the United States, which could tip the economy into a recession that monetary policy can do little to counter. More than usual, world economic prospects depend on events, the nature and timing of which are highly uncertain. The projections presented in this Economic Outlook portray a scenario that rests on the assumptions that monetary policy remains very supportive (and, in some places, becomes more so), that sovereign debt and banking sector problems in the euro area are contained and that excessive fiscal tightening will be avoided. From the second half of 2012, confidence is assumed to recover gradually as it becomes clearer that worst-case outcomes have been avoided. Near-term output growth is subdued in the OECD economies and at below-trend rates in the major emerging-market economies, developments which are likely to be associated with further short-term weakening of sentiment and confidence. In some economies, especially the euro area, a mild recession is projected in the near term. Alternative scenarios are possible, and may be even more likely than the baseline. A downside scenario would be characterised by materialisation of negative risks and the absence of adequate policy action to deal with them. An upside scenario could arise if policy action were successful in boosting confidence and no significant negative events occurred. In the downside scenario, the implications of a major negative event in the euro area will depend on the channels at work and their virulence. The results could range from relatively benign to highly devastating outcomes. A large negative event would, however, most likely send the OECD area as a whole

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

EDITORIAL: THE POLICY IMPERATIVE: REBUILD CONFIDENCE

into recession, with marked declines in activity in the United States and Japan, and prolong and deepen the recession in the euro area. Unemployment would rise still further. The emerging market economies would not be immune, with global trade volumes falling strongly, and the value of their international asset holdings being hit by weaker financial asset prices. What would be required for an upside scenario to materialise? A credible commitment by euro area governments that contagion would be blocked, backed by clearly adequate resources. To eliminate contagion risks, banks will have to be well capitalised. Decisive policies and the appropriate institutional responses will have to be put in place to ensure smooth financing at reasonable interest rates for sovereigns. This calls for rapid, credible and substantial increases in the capacity of the EFSF together with, or including, greater use of the ECB balance sheet. Such forceful policy action, complemented by appropriate governance reform to offset moral hazard, could result in a significant boost to growth in the euro area and the global economy. An upside scenario also requires substantial and credible commitment at the country level, in both advanced and emerging market economies, to pursue a sustainable structural adjustment to raise long-term growth rates and promote global rebalancing. In Europe, such policies are also needed to make progress in resolving the underlying structural imbalances that lie at the heart of the euro area crisis. Deep structural reforms will be instrumental in strengthening the adjustment mechanisms in labour and product markets that, together with a robust repair of the financial system, are essential for the good functioning of the monetary union. By raising confidence, lowering uncertainty and removing impediments to economic activity, rapid implementation of such reforms could raise consumption, investment and employment. If combined, stronger macroeconomic and structural policies might raise OECD output growth by as early as 2013. The largest benefits would be felt in the euro area, though these could take some time to emerge. Stronger activity and trade, and the consequent rise in asset values in the OECD economies, should boost activity in the emerging market economies as well. In view of the great uncertainty policy makers now confront, they must be prepared to face the worst. The OECD Strategic Response identifies country-specific policy actions that need to be implemented if the downside scenario materialises: the financial sector must be stabilised and the social safety net protected; further monetary policy easing should be undertaken; and fiscal support should be provided where this is practical. At the same time, stronger fiscal frameworks should be adopted to reassure markets that the public finances can be brought under control. Beyond this, a wide range of structural measures, which are desirable in their own right, will become urgent. While priorities vary from country to country, such policies include the removal of barriers in product and labour markets that inhibit economic activity and employment. Appropriate labour market policies are needed to deal with the consequences of unemployment which is turning from cyclical to structural, thereby sapping potential growth, hitting confidence and undermining public finances. The difference between the upside and the downside scenarios reflects the impact of credible, confidence building policy action. Such action, as we have seen, requires measures to be implemented at the euro area level as well as at the country level throughout the OECD, especially in the structural policy domain. In the case of a downside scenario, policy action would clearly be needed to avoid the worst outcomes. But then the question arises of why policy efforts are not taken to deliver the upside scenario even if the worst case does not materialise. Why, in other words, should we settle for less? 28 November 2011

Pier Carlo Padoan Deputy Secretary-General and Chief Economist

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

OECD Economic Outlook Volume 2011/2 OECD 2011

Chapter 1

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Summary

More than usual, world economic prospects depend on events, notably policy decisions related to the euro-area debt crisis and US fiscal policy. The nature and timing of many such events remain highly uncertain and the projection presented in this Economic Outlook therefore portrays a muddling-through case in the absence of decisive events. With this caveat, and against a profound loss of confidence related to the euro area debt crisis and US fiscal policy, the muddling-through projection involves very weak OECD growth in the near term, and a mild recession in the euro area, followed by a very gradual recovery. Concomitantly, unemployment would remain at a high level through 2013 and inflation would be under downward pressure in most regions. This calls for a continuation of present easy monetary policy stances for a considerable period and in some cases, most notably the euro area, a substantial relaxation of monetary conditions. Underlying budget consolidation is assumed to take place in most OECD countries; in the United States it is assumed to be weaker than embodied in current legislation, so as not to unduly restrain growth, and broadly in line with official consolidation plans in the euro area. In Japan, post-earthquake reconstruction spending will temporarily push up the budget deficit. With growth in emerging economies also having slowed and with high external surpluses in oilexporting countries, global current account re-balancing has stalled. Imbalances are projected to remain broadly stable, but at a lower level than before the 2008-09 crisis, as demand growth recovers slightly more rapidly outside the OECD area than within. Serious downside risks stem from the euro area, linked to further contagion in sovereign debt markets driven by the possibility of sovereign default and its associated cross-border effects on creditors and risks to the monetary union itself. Without preventive action, events could strengthen such pressures and plunge the euro area into a deep recession with large negative effects for the global economy. To stem contagion, banks will have to be seen as adequately capitalised and convincing capacity, and commitment to use it, will be needed to ensure smooth financing at reasonable interest rates for otherwise solvent sovereigns. Such action to address financial imbalances will need to be accompanied by governance reform to limit moral hazard and by decisive policy reform to address the economic imbalances at the root of the present crisis. Forceful policy action could result in a significant boost to growth in the euro area and the global economy. A serious downside risk is that no action will be agreed to counter strong, pre-programmed fiscal tightening in the United States. Much tighter fiscal policy than in the projection could tip the US economy into a recession that monetary policy can do little to prevent. The OECD Strategic Response to an economic relapse identifies country-specific policy recommendations that could be implemented if the economy turned out much weaker than projected: fiscal support, backed by improved fiscal frameworks, where the state of public finances and confidence allows; monetary policy easing where possible; and structural policy reforms to strengthen growth, lower unemployment and bolster confidence.

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

10

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Introduction

OECD activity is soft and the outlook uncertain

Global activity has slowed in emerging economies, where it reflects policies to rein-in inflationary pressures, and in OECD economies where it is associated with a sharp fall in confidence. The economic outlook is now more uncertain than usual, with a number of possible events related to the euro area debt crisis and fiscal policy in the United States likely to dominate economic developments in the coming two years. With the nature and timing of such events impossible to predict, a muddlingthrough projection is presented here, in which disorderly sovereign defaults, systemic bank failures and excessive fiscal tightening are assumed to be avoided. The risks around this projection emerge largely from OECD economies and are tilted to the downside. The muddling-through projection shows very weak OECD growth in the near term, and a mild recession in the euro area, followed by a soft and gradual recovery (Table 1.1). On this basis, unemployment would remain very high while inflation would drift down, though deflation would be avoided provided inflation expectations do not become

The muddling-through OECD projection is very weak in the near term followed by a muted recovery

Table 1.1. The global recovery has lost momentum

OECD area, unless noted otherwise

Average 1999-2008 2011 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2012 2013 Q4 / Q4

Per cent

Real GDP growth United States Euro area Japan Output gap2 Inflation4 Fiscal balance5

2.5 2.5 2.1 1.2 0.7 6.4 2.7 -2.2 6.7 3.8

-3.8 -3.5 -4.2 -6.3 -4.4 8.2 0.5 -8.3 -10.7 -1.2

3.1 3.0 1.8 4.1 -3.2 8.3 1.8 -7.7 12.6 5.0

1.9 1.7 1.6 -0.3 -3.1 8.0 2.5 -6.6 6.7 3.8

1.6 2.0 0.2 2.0 -3.4 8.1 1.9 -5.9 4.8 3.4

2.3 2.5 1.4 1.6 -3.1 7.9 1.5 -5.1 7.1 4.3

1.6 1.5 0.9 0.8 8.1 2.6

1.8 2.0 0.6 1.7 8.1 1.7

2.5 2.7 1.7 1.6 7.8 1.5

Unemployment rate3

Memorandum Items World real trade growth World real GDP growth6 5.1 3.4 5.7 3.6 7.7 4.6

1. Year-on-year increase; last three columns show the increase over a year earlier. 2. Per cent of potential GDP. 3. Per cent of labour force. 4. Private consumption deflator. Year-on-year increase; last 3 columns show the increase over a year earlier. 5. Per cent of GDP. 6. Moving nominal GDP weights, using purchasing power parities. Source: OECD Economic Outlook 90 database.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932541626

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

11

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

unanchored. In emerging market economies, inflation is projected to ease as pressures on resources dissipate, with growth staying soft in the near term. The outlook would be much darker if negative events were to occur, notably those that could lead to an intensification of concerns about the robustness of the banking system and contagion in euro-area sovereign debt markets, or an excessively tight fiscal policy in the United States due to political gridlock. On the other hand, prospects for the global and OECD economy could become significantly brighter if measures were taken to successfully stem pressures in the euro area and a credible medium-term fiscal programme was to be enacted in the United States. This chapter is organised as follows. After briefly reviewing the main forces at work, it sets out the muddling-through projection and policy requirements consistent with such an outlook. It then turns to the consequences of alternative scenarios in the euro area, assessing the strength of the different contagion channels and the resources and policies required to stem contagion. An alternative fiscal scenario in the United States is then presented, based on different assumptions about the future stance of fiscal policy. Finally, the chapter sets out key macroeconomic policy requirements and structural reform measures that would become more urgent should activity turn out to be significantly weaker than projected.

Key forces acting

The recovery is close to halting

The recovery in the OECD area has now slowed to a crawl, notwithstanding a short-lived rebound from the restoration of global supply chains disrupted by the Japanese earthquake and its aftermath. Emerging market output growth has also continued to soften, reflecting the impact of past domestic monetary policy tightening, sluggish external demand and high inflation. Against this background, the protracted fiscal-policy discussions in the United States and the deepening euro area crisis have highlighted the role of destabilising events and policies as well as the reduced political and economic scope for macroeconomic policies to cushion economies against further adverse shocks. In turn, this has heightened risk awareness and uncertainty, with a corresponding drop in confidence, both in financial markets and in the non-financial private sector. Lower confidence will weigh on the global economy in the coming quarters. Key forces acting include:

Business and consumer sentiment has plummeted

Business and consumer sentiment and order books have dropped sharply since the summer in most OECD and non-OECD economies, with Japan being a notable exception. In most cases though, indicators have not reached the levels observed at the depth of the crisis in 2008-09 (Figure 1.1). The PMI surveys in the major global economies now point to weak or, especially in the euro area, no growth in the near term. Survey measures of hiring intentions have also softened in many cases, particularly in Europe, pointing to a continuation of recent upticks in unemployment.

12

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Figure 1.1. Business surveys point to a much weaker outlook

Difference between the net PMI balances for new orders and the stock of finished goods, normalised

United States

3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5

Japan

3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Euro area

3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5

China

3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Note: PMI expressed in units of standard deviations around average. Source: Markit; and OECD calculations.

and global activity and commodity prices have weakened

Trade-related indicators, such as export order books and container shipping rates, point towards weak global trade growth in the near term. Widespread flooding in Thailand has also begun to generate renewed disruptions in global supply chains, which will further damp trade growth temporarily. The softening in global demand has begun to be reflected in global commodity prices, but only to a relatively limited extent to date, especially in oil markets. This may reflect expectations of continued relatively strong growth in comparatively commodityintensive emerging market economies. Even so, the easing of commodity prices that has already occurred should provide a modest fillip to the OECD economies (whose growth might otherwise have been even weaker) by up to percentage point per annum, over the next two

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

13

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

years. It will also act to further ease recent pressures on headline inflation.

Heightened risk has spurred considerable financial market turbulence

Higher perceived risk has generated considerable turbulence in financial markets. Equity prices have declined markedly (Figure 1.2), especially for banks in the euro area but also worldwide;1 bank credit default swap rates have increased sharply, in both Europe and the United States, reflecting renewed concerns about banks solvency (Figure 1.3); and the widening of sovereign yield spreads has become generalised beyond euro area programme countries (Figure 1.4). The funding pressures on the banking sector are likely to result in moves towards tighter credit standards, with the first tangible evidence provided by the latest ECB Bank Lending Survey and the US Senior Loan Officer Survey.2 The flipside of risk re-evaluation has been a substantial decrease in the yields on safe-haven government bonds and top-rated corporate bonds, in some cases to historic lows. The US dollar, the yen and the Swiss franc effective exchange rates have appreciated significantly since mid-year, on the back of safe-haven effects.3 Putting these developments together, the OECD financial conditions indices (FCIs) show divergent developments across countries (Figure 1.5): a deterioration in the euro area and, more recently, in the United States, implying that GDP growth could be reduced respectively by 1 and percentage point in 2012 and and percentage point in 2013 compared with the outcome if the FCI had not deteriorated; but some improvement in Japan. Financial conditions in emerging economies are becoming less supportive of growth. Sovereign bond spreads have risen, equity prices have declined and credit growth has slowed, including in China; several economies have also recently experienced sizeable exchange rate depreciations against the US dollar, reversing the tendency prevailing earlier in the year. In addition, indicators of uncertainty in financial markets, as reflected in the daily volatility of equity markets, have risen sharply, back towards the high levels last seen in 2008-09. Such uncertainty, which is not included directly in the FCIs, is likely to result in the postponement of some planned, but hard-to-reverse, expenditures, especially by companies, and also delay hiring decisions (Box 1.1).

including in emerging markets

and has raised uncertainty

1. With equity prices low relative to cyclically-averaged earnings, their recent correction may in part reflect a rise in the equity risk premium given heightened uncertainty. 2. The ECB survey showed that a balance of respondents are now tightening credit standards in the euro area, and the US survey showed that fewer respondents are now easing credit standards. In both cases, these changes serve to make financial conditions less growth-friendly than would otherwise have been the case. 3. In response to upward pressure on the Swiss Franc, the Swiss National Bank capped its value at SFr 1.2 per euro through unlimited intervention.

14

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Figure 1.2. Equity markets have weakened again

Index 2000=100

United States

Wilshire 500

Japan

Nikkei 225

160 140 120 100 80 60 40 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

160 140 120 100 80 60 40

Euro area

FTSE Eurotop 100

United Kingdom

FTSE 100

160 140 120 100 80 60 40 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

160 140 120 100 80 60 40

Canada

Composite

China

Shangai Composite 400

160 140 120 100 80 60 40 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

different scale

350 300 250 200 150 100 50

Latin America

MSCI EM

Emerging Europe

MSCI EM

160 140 120 100 80 60 40 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

160 140 120 100 80 60 40

1. The MSCI index for Emerging Europe also includes Middle-East and Africa. Source: Datastream.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540239

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

15

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Figure 1.3. It has become more expensive to insure unsecured bank debt against default

Annual rates of five-year credit default swap contracts on very large banks

Basis points 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 Basis points 400 350 300 250 200 150 100 50 0

United States

Euro area

United Kingdom

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

Q4

Jul

Aug Sep Oct Nov 2011

Note: Banking sector 5-year credit default swap rates. Source: Datastream.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540258

Figure 1.4. Investors are now discriminating strongly across euro area sovereign bonds

10-year sovereign bond yield, in per cent

35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Q4 Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov 2011 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0

Germany Greece

Portugal Ireland

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Germany France

Italy Spain

Belgium Austria

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011

Q4

Jul

Aug Sep Oct Nov 2011

Source: Datastream.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540277

16

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Figure 1.5. Overall financial conditions have been hit in the euro area

6

United States Japan Euro area

-2

-2

-4

-4

-6

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

-6

Note: A unit increase (decline) in the index implies an easing (tightening) in financial conditions sufficient to produce an average increase (reduction) in the level of GDP of to 1% after four to six quarters. See details in Guichard et al. (2009). Estimation done with available information up to 17 November 2011. Source: Datastream; OECD Economic Outlook 90 database; and OECD calculations.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540296

This is placing renewed pressures on household balance sheets

Household balance sheets have begun to weaken once more in some economies, reflecting the adverse effects of lower equity prices and persistent housing market weakness, with real house prices now declining in around two-thirds of the OECD countries for which timely estimates are available.4 This is likely to contribute to keeping household saving rates elevated for some time to come, to help repair balance sheets. In addition, reflecting the widespread slack remaining in labour markets and the upturn in headline inflation this year, real wage and household income growth remains modest, holding back household consumption growth. Over and above effects from balance sheets and real income, the large recent declines in consumer confidence could also damp consumption growth in the near term (Box 1.1).

4. The direct impact of lower equity prices in the United States and the euro area could imply an eventual reduction in household consumption of just under 1%. In the United States, equity prices have declined by around 8 per cent since the end of the first quarter, reducing the value of household financial assets by around $1.6 trillion, taking into account the impact on the value of equities held directly by households and indirectly through pension funds and mutual funds. Assuming a marginal propensity to consume out of financial wealth of 6 cents per dollar (Carroll et al., 2011), this implies an eventual reduction in household consumption of around 0.9%. The equivalent calculations for the euro area, where equity prices have declined by close to 25% since the end of the first quarter, imply a reduction in household consumption of 0.8%. The wealth calculations for the euro area take account of quoted equities, unquoted equities and mutual funds held directly by households and indirectly through insurance and pension funds. Equity price changes are assumed to apply to 40% of unquoted equity holdings and 30% of mutual fund holdings.

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

17

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Box 1.1. Risk awareness, uncertainty and confidence

Recent economic developments have been accompanied by heightened risk awareness and uncertainty, and sharp falls in confidence, both in financial markets and in the non-financial private sector. Such changes are often taken as an early, and timely, indicator of short-term cyclical swings in activity. This is especially so for hard and costly to reverse decisions, such as fixed investment, new hiring and purchase of durable goods. For such decisions, heightened uncertainty raises the option value of waiting, and hence weakens near-term expenditure (Bernanke, 1983; Pindyck, 1991; Bloom, 2009 and 2011). Equally, movements in survey-based indicators of consumer confidence have also been found to have a direct significant association with current and future private consumption growth (Nahuis and Jansen, 2004), particularly if the movements are large (Dees and Brinca, 2011), even if other factors such as income and wealth are taken into account (Carroll et al., 1994; Ludvigson, 2004; Wilcox, 2007). Two important issues are whether there is a consistent, statistically significant and economically relevant relationship over time between private expenditure and measures of confidence and uncertainty, and whether there is independent information in measures of uncertainty and confidence relevant for understanding near-term developments in private expenditure. To assess these, the OECD has developed simple quarterly indicator-type models for consumption growth and business investment growth in the United States and the euro area (see Jin et al., 2011). These quarterly equations are augmented by separate monthly models for business and consumer confidence. The results confirm that uncertainty, proxied by the VIX and VSTOXX indices measures of the respective daily implied volatility of the US and euro area equity markets and confidence measures influence private spending after accounting for other financial market developments (as reflected in the OECD financial condition indices):

Business survey measures of investment intentions and production expectations are found to be strongly associated with quarterly changes in capital spending in the United States and the euro area, respectively. Monthly changes in the business survey measures are themselves found to be affected directly by monthly changes in stock market uncertainty. In addition, quarterly changes in stock market uncertainty are found to have a separate direct impact on investment spending in the United States, but not in the euro area. The quarterly growth of consumer spending is found to be linked to aggregate consumer confidence indicators in both the United States and the euro area, but it does not seem to be affected directly by measures of stock market uncertainty.

The empirical results have been used to produce a profile for business investment and private consumption growth over the coming two years. In both cases, financial conditions are assumed to remain fixed at their last observed level (see main text for details). The results presented here should be distinguished from the main projection where a broader range of factors are incorporated.

For the investment path, stock market uncertainty is assumed to remain elevated until the end of the first quarter of next year, before reverting to its mean value by mid-2012. The resulting estimates, set out in the first figure below, indicate that near-term business investment growth in the euro area could be particularly subdued, unless uncertainty was to suddenly subside. In both economies, the projected outcome from these equations is somewhat weaker than in the muddling-through projection. This is particularly so in the euro area, where quarterly declines are projected by the indicator equation until the latter half of 2012; in contrast, the muddling-through projection is for weak, but positive investment growth from the second quarter of 2012. For the consumption path, consumer confidence is assumed to decline marginally further in the fourth quarter of 2011, and then remain unchanged until mid-2012 before reverting towards longer-term norms thereafter. On this basis, the resulting estimates set out in the second figure below point to small quarterly declines in consumption in the first half of next year in the euro area and little or no growth in the United States; these are somewhat weaker outcomes than incorporated in the muddling-through projection.

18

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Box 1.1. Risk awareness, uncertainty and confidence (cont.) The implications of confidence and uncertainty for expenditure growth

Quarter-on-quarter growth rate in per cent

Business Investment

5 5

0

United States Euro area

-5

-5

-10

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

-10

Household consumption

1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 -1.5

United States Euro area

1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -1.0

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

-1.5

Source: OECD calculations.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540334

Several factors may cushion the lapse in activity

Set against the negative factors above, the extent of any further weakness in activity may be damped by adjustments that have been ongoing since the onset of the recession in 2008. In particular, balance sheets are already adjusting at a sustained pace, which may limit the need for a further large precautionary upward adjustment in private sector saving rates in response to weaker asset prices. Many companies also have large cash holdings, which could be used as a buffer to help support employment and investment if sluggish growth is expected to be only short lived. Survey indicators also suggest that inventories have not yet risen to the excessive levels attained in 2008-09, reducing the likelihood that weakness in final demand will be reinforced by a large contraction in inventory levels. Similarly, other cyclically-sensitive categories of expenditure, notably housing investment and consumer durables, now account for a much lower share of final expenditure than in 2006-07.

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

19

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

The muddling-through projection

Conditional on particular assumptions, growth is likely to remain weak and recover only slowly

The projections presented here rest on a tacit assumption that sovereign debt and banking sector problems in the euro area can be somehow contained and the assumption that excessive, pre-programmed fiscal tightening will be avoided in the United States. Against this backdrop, near-term output growth is projected to be subdued in the OECD economies and at below-trend rates in the major emerging market economies. In some economies, especially the euro area, a mild recession is projected in the near term. Ongoing support is provided by accommodative monetary policies throughout the projection period (Box 1.2), but continued fiscal consolidation and weak labour, housing and credit markets will all act to check growth. Further ahead, from the latter half of 2012, the recovery is thus likely to be only modest, reflecting the gradual speed and extent to which confidence is assumed to recover as it

Box 1.2. Policy and other assumptions underlying the projections

Fiscal policy settings for 2012 and 2013 are based as closely as possible on legislated tax and spending provisions. Where government plans for 2012-13 have been announced but not legislated, they are incorporated if it is deemed clear that they will be implemented in a shape close to that announced. Otherwise, in countries with impaired public finances, a tightening of the underlying primary balance of about and 1% of GDP in 2012 and 2013, respectively, has been built into the projections. Where there is insufficient information to determine the allocation of budget cuts, the presumption is that they apply equally to the spending and revenue side, and are spread proportionally across components. These conventions allow for needed consolidation in countries where plans have not been announced at a sufficiently detailed level to be incorporated in the projections. Along this line, the following assumptions were adopted (with additional adjustments if OECD and government projections for economic activity differ): For the United States, the assumptions for 2011 are based on legislated measures. Given the legislative uncertainty about budget policy for 2012 and 2013, the general government underlying primary balance is assumed to improve by and 1 per cent of GDP in 2012 and 2013, respectively. For Japan, the projections are based on the revised Medium-term Fiscal Framework announced in August 2011 which limits the issuance of new government bonds (excluding bonds to finance earthquakerelated reconstruction) in FY 2011-12 to the FY 2010 level. The projection also includes reconstruction spending of around 19 trillion yen (about 4% of GDP) over five years and the planned tax increases of around 11 trillion yen (about 2% of GDP) over a period of up to 25 years to finance such spending. For Germany, the governments medium-term consolidation programme, announced in September 2010, as well as the phasing out of the temporary components of the fiscal stimulus packages have been built into the projections, including recently announced measures aimed at compensating for weaker growth. For France, the projections incorporate the governments medium-term consolidation programme. For Italy the projections incorporate legislation up to and including the September Emergency Budget, and additional tightening needed to respect the governments commitment to a near-zero deficit in 2013 given that projected activity is lower than that on which the budget legislation is based. For the United Kingdom, the projections are based on tax measures and spending paths set in the March 2011 budget.

20

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Box 1.2. Policy and other assumptions underlying the projections (cont.)

The concept of general government financial liabilities applied in the OECD Economic Outlook is based on national accounting conventions. These require that liabilities are recorded at market prices as opposed to constant nominal prices (as is the case, in particular, for the Maastricht definition of general government debt). In 2010, euro area countries with unsustainable fiscal positions that have asked for assistance from the European Union and the IMF (Greece, Ireland and Portugal) experienced large declines in the price of government bonds. For the purpose of making the analysis in the Economic Outlook independent from strong temporary fluctuations in government debt levels on account of valuation effects, for these countries, the change in 2010 in government debt has been approximated by the change in government liabilities recorded for the Maastricht definition of general government debt. Given uncertainty about the precise amounts involved, no adjustment has been made for Greek government debt write-down as agreed at the 26 October Euro summit. Policy-controlled interest rates are set in line with the stated objectives of the relevant monetary authorities, conditional upon the OECD projections of activity and inflation, which may differ from those of the monetary authorities. The interest rate profile is not to be interpreted as a projection of central bank intentions or market expectations thereof.

In the United States, the target Federal Funds rate is assumed to remain constant at per cent for the entire projection horizon. In the euro area, the overnight rate is assumed to fall to 0.35 per cent by the end of 2011 through cuts in the repo and deposit rates and expanded liquidity provision, and remains constant until the end of 2013. In Japan, the current interest rate policy needs to be continued until inflation is firmly positive. The short-term policy interest rate is assumed to remain at 10 basis points for the entire projection horizon. In the United Kingdom, the policy interest rate is assumed to remain constant at per cent for the entire projection horizon. The Bank of England is assumed to announce an additional bond purchase programme of 125 billion in early 2012. The additional purchases are assumed to keep longer-term interest rates 50 basis points below the path which they would have been assumed to follow without this measure.

For the United States, Japan, Germany and other countries outside the euro area, 10-year government bond yields are assumed to converge slowly toward a reference rate (reached only after the projection period), determined as future projected short rates plus a term premium and an additional fiscal premium. The latter premium is assumed to be 2 basis points per percentage point of gross government debt-GDP ratio in excess of 75 per cent and an additional 2 basis points (4 basis points in total) per percentage point of the debt ratio in excess of 125%. For Japan, the premium is assumed to be 1 basis point per percentage point of gross government debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 75%. The long-term sovereign debt spreads in the euro area vis--vis Germany are assumed to halve in the course of 2013 for all other euro area member countries. The projections assume unchanged exchange rates from those prevailing on 14 November 2011: $1 equals 76.98 JPY, 0.734 (or equivalently, 1 equals $1.36) and CNY 6.35. The price of a barrel of Brent crude oil is assumed to be constant at $110 from the fourth quarter of this year onwards. Non-oil commodity prices are assumed to be constant over the projection period at the average level in October 2011. The cut-off date for information used in the projections is 22 November 2011. Details of assumptions for individual countries are provided in Chapters 2 and 3.

becomes clear that other, worst-case, scenarios have been avoided. The key features of the economic outlook for the major economies are as follows:

in the United States

Growth in the United States is expected to remain fairly subdued through 2012 before gradually picking up. Weak confidence, soft

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

21

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

employment growth and the renewed pressures on balance sheets from lower asset values are all likely to damp consumers expenditure. Heightened uncertainty should also moderate business investment growth in the near term, despite healthy corporate balance sheets. Continued fiscal consolidation, although assumed to be at a more moderate pace than in 2011, will also hold back activity. Provided confidence recovers during 2012, as assumed, accommodative monetary policy and strengthening external demand should help to buoy activity through 2013, allowing the sizable negative output gap to narrow marginally. But, despite a pick-up in employment growth, the unemployment rate is projected to remain elevated, declining only to around 8 per cent by the end of 2013.

in the euro area

The euro area is seen to have entered a mild recession, which will be followed by an only hesitant pick-up in activity. Deteriorating financial conditions and ongoing fiscal consolidation, with several countries having announced additional consolidation in the light of heightened concerns about sovereign debt sustainability, will act as a drag on the economy in both 2012 and 2013. In the near term, with output expectations continuing to decline and the loss of momentum in the economy, business investment is likely to be very weak. Softening confidence, deteriorating labour market conditions and renewed balance-sheet pressures are also likely to weigh on private consumption. Provided sovereign debt and banking problems can be contained, as assumed, and supportive monetary policy actions are undertaken, confidence should gradually recover from the latter half of next year. However, the large negative output gap is projected to close only marginally in 2013. The unemployment rate is projected to remain elevated, at just over 10% at the end of 2013. After an initial rapid rebound in activity following the earthquake and the Fukushima disaster, the pace of the recovery is now moderating. Financial conditions have improved modestly through 2011, providing a stimulus to activity in 2012, and the planned fiscal package (worth 2% of GDP) is likely to boost growth by next year. Ongoing private and public reconstruction expenditure should help to support demand, though the timing of such expenditure remains uncertain. Soft global growth and the appreciation of the real exchange rate are, however, likely to check the pace of the upturn. As public reconstruction efforts fade, stronger business investment and a gradual improvement in labour market conditions should support the recovery, and allow the negative output gap to diminish gradually through the projection period. The contribution of emerging markets to global growth is substantial at present (Figure 1.6), and likely to remain so. Even so, output growth in China is projected to be well below potential in the near term. Domestic demand is likely to be relatively resilient, helped by increasing public

in Japan

and in emerging markets

22

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Figure 1.6. Global growth is heavily dependent on the non-OECD economies

Contribution to annualised quarterly world real GDP growth

% 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6 -8

OECD Non-OECD

% 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6 -8

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Note: Calculated using moving nominal GDP weights, based on national GDP at purchasing power parities. Source: OECD Economic Outlook 90 database.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540315

spending on social housing, but net trade is likely to be a drag on activity, reflecting both strong import growth and, in the near term, soft external demand. As inflation and monetary conditions ease, GDP is expected to pick up from around the middle of 2012 and to grow at rates close to 10% through 2013. In India, the recent moderation in activity is expected to persist through to mid-2012, given tight monetary conditions, leading to a wider negative output gap. Improving domestic confidence, easier monetary conditions and stronger external demand should help growth to pick up to around 8 per cent in 2013. In Brazil, domestic demand is projected to remain solid over the next two years, helped by large infrastructure programmes. However, the ongoing drag exerted by net export declines should keep GDP growth below potential rates, at around 3-4 per cent per annum. In Russia, GDP growth is expected to remain close to potential rates, at around 4% per annum, sustained by the still-high level of oil prices.

subduing world trade growth

World trade growth is expected to broadly follow its normal pattern relative to world GDP growth through the projection period, picking up from an annualised rate of 3 per cent in the fourth quarter of this year, to around 8% by the latter half of 2013. A benchmark dynamic-factor model of trade growth (Guichard and Rusticelli, 2011), using a wide range of trade indicator variables, shows that there is a risk that trade growth could be softer than projected in the near term, and possibly even decline in the fourth quarter.

Inflation is peaking

Annual rates of headline consumer price inflation in most OECD and emerging market economies have now started to decline. Much of the previous run-up had stemmed from the comparative strength of

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

23

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

commodity prices, especially in many emerging market economies. However, core inflation rates, abstracting from the direct effects of food and energy price inflation, have also drifted up this year, in part due to increases in indirect taxes and administered prices in several OECD economies and the effects of domestic capacity constraints in economies such as China, India and Brazil. Long-term inflation expectations in the OECD economies, especially as represented by survey-based measures, appear to remain reasonably well anchored.5

... and will weaken steadily

Weakened commodity prices will help to quickly bring down headline inflation rates. Moreover, continued, and in some cases widening, negative output gaps in the OECD economies should bear down on inflation through much of the projection period (Figure 1.7 and Box 1.3).6 Continued labour market slack should also ensure that labour

Box 1.3. The anchoring of inflation expectations and the risk of deflation

With growth prospects weakening in an environment characterised by low core inflation and still ample economic slack, concerns about deflation risk have re-emerged. Stable inflation expectations can serve as a powerful buffer against entering a deflationary spiral, raising a question as to how stable these expectations really are. One means of evaluating the relationship between inflation expectations and realised inflation is to regress indicators of inflation expectations on current and lagged consumer price inflation, using a rolling window, and study the development of the sum of the estimated coefficients (Trehan 2010). In the regression results depicted below, a 15-year rolling window is used and the number of lags is set to seven quarters. The results from regressing US consumers short-run or long-run inflation expectations on headline inflation show that the sum of the estimated coefficients is currently lower than in 2007. Results using professional forecasters short-run or long-run inflation expectations are similar. These findings suggest that changes in headline inflation have had a declining impact on inflation expectations. For the euro area, results from regressing professional forecasters short-run or long-run inflation expectations on headline inflation show that the sum of the estimated coefficients continues to be low. Therefore, even after the experience of large swings in headline inflation, inflation expectations appear to be well-anchored. This result might give grounds to hope that projected falls in headline inflation, due to weaker economic developments and falls in commodity prices, will not reduce inflation expectations sufficiently to pose significant deflation risk in the muddling-through projection. For instance, based on the coefficient estimates for the most recent period, the one percentage point fall in headline US CPI inflation in the projection between end-2011 and end-2012 would be associated with one-year-ahead inflation expectations falling by roughly percentage point over the same period. This itself contributes percentage point to the fall in core inflation in 2013 based on the expectations-based Phillips curve estimated in Moccero et al. (2011). Similarly, in the euro area, the percentage point decline in headline inflation between end-2011 and end-2012 would reduce one-year-ahead inflation expectations by percentage point, which in turn would subtract percentage point from core inflation in 2013.

5. Some signs of weaker inflation expectations have begun to appear in marketbased measures derived from yield differences between nominal and indexed bonds, but in part this reflects a mis-measurement generated by the flight to more liquid nominal bonds during renewed financial turmoil. 6. Empirical evidence suggests that the effects of economic slack on inflation are much weaker now than in the past (Koske and Pain, 2008; Moccero et al., 2011).

24

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Box 1.3. The anchoring of inflation expectations and the risk of deflation (cont.) Sensitivity of various measures of inflation expectations to headline inflation

Estimated response of inflation expectations to a one percentage point change in headline inflation

United States

One year-ahead

1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.2

United States

5-10 year-ahead

1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.2

2007

2008

2009

2010

2007

2008

2009

2010

United States

One year-ahead

1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.2

United States

10 year average

1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.2

2007

2008

2009

2010

2007

2008

2009

2010

Euro area

One year-ahead

1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.2

Euro area

5 year-ahead

1.2 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.0 -0.2

2007

2008

2009

2010

2007

2008

2009

2010

Note: Dotted lines show 90 per cent confidence interval computed by a bootstrap procedure. 1. Based on inflation expectations from Reuters/University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers. 2. Based on inflation expectations from US Survey of Professional Forecasters. 3. Based on inflation expectations from ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters. Source: Datastream; ECB; and OECD calculations.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540391

cost pressures remain weak. In the United States and the euro area, the annualised rate of core inflation is projected to drift down to around 1 per cent over the projection period. Deflation is expected to persist in Japan, albeit at a gradually diminishing pace. In emerging countries, slower current and future growth should suffice to alleviate inflationary tensions arising from domestic capacity constraints.

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

25

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Figure 1.7. Underlying inflation is likely to moderate

12-month percentage change

United States

% 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Headline PCE deflator PCE deflator excluding food and energy Unit labour costs

% 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3

Euro area

% 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Headline HICP HICP excluding food, energy, tobacco and alcohol Unit labour costs

% 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 -1 -2 -3

Japan

% 8 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6

Headline CPI CPI excluding food and energy Unit labour costs

% 8 different scale 6 4 2 0 -2 -4 -6

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Note: PCE deflator refers to the deflator of personal consumption expenditures, HICP to the harmonised index of consumer prices and CPI to the consumer price index. Unit labour costs are economy-wide measures. Source: OECD Economic Outlook 90 database.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540353

26

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Labour markets are now weakening once more

Following a brief period of improving outcomes, unemployment is now rising once more in several economies, especially in Europe. The projection builds in an assumption that, as in 2008-09, widespread labour hoarding will help to preserve employment through a prolonged period of sub-par growth. Short-time working arrangements could, in principle, facilitate such labour hoarding, but their use may now be reduced, as average hours worked have still not returned to pre-crisis norms in many companies. If working hours do not adjust as much as in 2008-09, companies will either have to accept weak productivity growth as the counterpart to labour hoarding or lay off workers faster than projected. In the projection, total OECD employment rises by between - per cent in 2012 and 2013 (Table 1.2), with ongoing job growth in the United States offset in part by job losses in some European economies and Japan. The OECD-wide unemployment rate is projected to decline by only a percentage point over the two years to the fourth quarter of 2013. This would leave a large and persistent degree of labour market slack in most OECD economies (Figure 1.8), despite the extent to which factors such as higher long-term unemployment and unemployment benefit extensions may have pushed up the structural rate of unemployment in recent years.

... and little improvement is foreseen

Table 1.2. OECD labour market conditions are no longer improving

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Percentage change from previous period

Employment United States Euro area Japan OECD Labour force United States Euro area Japan OECD Unemployment rate United States Euro area Japan OECD

-0.5 0.9 -0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 -0.3 1.0

-3.8 -1.8 -1.6 -1.8 -0.1 0.3 -0.5 0.5

-0.6 -0.5 -0.4 0.3 -0.2 0.1 -0.4 0.5

0.5 0.2 -0.1 1.2 -0.1 0.1 -0.6 0.8

1.2 -0.3 -0.4 0.5 1.1 0.2 -0.5 0.6

1.5 0.2 -0.4 0.8 1.1 0.2 -0.5 0.6

Per cent of labour force

5.8 7.5 4.0 6.0

9.3 9.4 5.1 8.2

9.6 9.9 5.1 8.3

9.0 9.9 4.6 8.0

8.9 10.3 4.5 8.1

8.6 10.3 4.4 7.9

Source: OECD Economic Outlook 90 database.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932541645

Structural measures are essential to help tackle rising unemployment

Labour market policies can help to foster near-term employment growth and minimise the employment costs of the downturn.7 Factors that are likely to be of particular importance for raising hiring incentives

7. A full range of structural reforms that could help to increase near-term employment growth and minimise the employment cost of the downturn are discussed in detail in OECD (2011a).

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

27

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Figure 1.8. Considerable labour market slack is set to persist

Percentage of labour force

Unemployment and estimated NAIRU in the OECD area

% 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

NAIRU Unemployment

% 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

2010

Unemployment in the three main regions

% 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

United States Euro area Japan

% 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

1. NAIRU is based on OECD Secretariat estimates. For the United States, it has not been adjusted for the effect of extended unemployment benefit duration. Source: OECD Economic Outlook 90 database.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540372

include: strengthening public employment services and training programmes to improve the matching of workers and jobs; rebalancing employment protection towards less-strict protection for regular workers, but more protection for temporary workers; and temporary reductions in labour taxation, where feasible through well-targeted marginal job subsidies (for new hires where net jobs are rising) rather than via across-

28

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

1. GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

the-board reductions in payroll taxes. Reforms to relax regulatory restrictions in sectors in which there is a strong potential for new job growth, such as retail trade and professional services, could also serve to improve labour market outcomes relatively quickly. Some of the measures that would help to stimulate employment in the near term could also reduce the risk of the transformation of cyclical into structural unemployment and strengthen labour market performance more generally. Other possible measures that might help to improve long-term labour market outcomes, such as reductions in unemployment benefit duration, may have more negative social consequences when labour demand is weak and should be pursued in the current context only when existing policy is clearly excessive.

Current account imbalances are likely to remain elevated

The narrowing of global imbalances since the advent of the crisis in 2008 has now slowed, and imbalances seem likely to remain broadly stable over the projection period (Figure 1.9, Table 1.3). The sum of all external balances in absolute terms is projected to remain around 3 per cent of world GDP over the projection period, well below the level immediately prior to the crisis. Global imbalances are being kept elevated, at least in part, by the large increase in the external surpluses of the highsaving oil-producing economies, on the back of the still-high level of oil prices. Whilst re-spending of oil revenues is likely to reduce the external surpluses of oil-producing economies somewhat, much of the additional

Figure 1.9. Global imbalances remain elevated

Current account balance, in per cent of world GDP

%

3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 -1.5 -2.0 -2.5

United States Japan Germany China Major oil exporters Euro area excluding Germany Rest of the world

%

3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 0.0 -0.5 -1.0 -1.5 -2.0

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

-2.5

Note: The vertical dotted line separates actual data from forecasts. 1. Include Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Brunei, Timor-Leste, Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya, Oman, Qatar, Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Ecuador, Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela, Algeria, Angola, Chad, Rep. of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Nigeria and Sudan. Source: OECD Economic Outlook 90 database.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932540410

OECD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK, VOLUME 2011/2 OECD 2011 PRELIMINARY VERSION

29

1.

GENERAL ASSESSMENT OF THE MACROECONOMIC SITUATION

Table 1.3. World trade is slowing and imbalances remain

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Goods and services trade volume World trade1 of which: OECD OECD America OECD Asia-Pacific OECD Europe China Other industrialised Asia2 Russia Brazil Other oil producers Rest of the world OECD exports OECD imports Trade prices3 OECD exports OECD imports Non-OECD exports Non-OECD imports Current account balances United States Japan Euro area OECD China United States Japan Euro area OECD China Other industrialised Asia2 Russia R i Brazil Other oil producers Rest of the world Non-OECD World -2.7 2.8 0.0 -0.5 5.2 -377 143 8 -205 261 131 49 -24 92 -86 423 218 -10.7 -12.0 -12.5 -12.7 -11.6 -4.0 -10.1 -17.2 -10.9 -3.7 -10.6 -11.6 -12.4 -9.2 -11.2 -13.7 -9.4

Percentage change from previous period

12.6 11.4 13.0 15.4 9.8 24.8 17.4 14.6 24.4 1.0 8.5 11.5 11.3 2.6 3.6 11.1 9.6

6.7 5.7 6.2 5.7 5.5 9.9 8.3 9.4 9.0 6.4 9.6 6.0 5.4 9.5 10.7 15.7 12.8

Per cent of GDP

4.8 3.8 4.9 6.7 2.7 10.4 5.8 4.7 11.5 5.4 3.8 4.1 3.5 -0.4 -0.4 1.3 1.6

7.1 6.1 6.6 7.4 5.5 12.4 8.6 6.5 11.8 7.4 5.6 6.2 5.9 1.3 1.3 1.5 1.4

-3.2 3.6 0.2 -0.6 5.2 -471 196 27 -252 305 105 70 -47 249 -107 576 324

-3.0 2.2 0.1 -0.6 3.1

$ billion

-2.9 2.2 0.6 -0.4 2.6 -463 136 81 -203 224 120 78 -56 452 -184 634 431

-3.2 2.4 1.0 -0.4 2.1 -519 153 138 -206 204 130 70 -70 439 -172 600 394

-455 130 10 -284 230 110 102 -49 498 -185 707 423

Note: Regional aggregates include intra-regional trade. 1. Growth rates of the arithmetic average of import volumes and export volumes. 2. Chinese Taipei; Hong Kong, China; Malaysia; Philippines; Singapore: Vietnam; Thailand; India and Indonesia. 3. Average unit values in dollars. Source: OECD Economic Outlook 90 database.

1 2 http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932541664

revenue accrued is likely to be saved, as appropriate for countries in which oil reserves are being depleted gradually. In the major economies, a deterioration of the oil trade balance has been an important factor behind recent changes in external imbalances. In the nine months to September, this deterioration more than accounted for the nominal decline in the aggregate external trade surplus of China, compared with the same period a year ago; in the United States it accounted for around two-thirds of the rise in the external trade deficit

30