Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Aircraft British Archaeology 75, March 2004

Enviado por

LibroColDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Aircraft British Archaeology 75, March 2004

Enviado por

LibroColDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

British Archaeology 75, March 2004

http://www.britarch.ac.uk/ba/ba75/feat1.shtml

features

Who Owns Our Dead?

Archaeologists value human remains for all they can tell about the past, but the issues now provoke strong debate. In the UK this mostly concerns ancient bones or recent people from far away. World War II fatalities are different, raising awkward questions for archaeologists, collectors and government. In the first of two provocative pieces, Vince Holyoak looks back to the last war fought in British skies

CBA web:

British Archaeology

February 2001 April 2001 June 2001 August 2001 October 2001 December 2001 Issue 75 February 2002 Breakfast, Friday 6 September 1940. Cathode ray displays at RAF radar stations on Englands south coast begin to fill with returns as Luftwaffe aircraft jockey into position April 2002 March 2004 June 2002 over northern France. By 8.40 Observer Corps posts can actually see the enemy August 2002 formations approaching. Six squadrons of Spitfires and Hurricanes are scrambled. Contents October 2002 Taking off from Middle Wallop in Hampshire, bucking and weaving as they climb furiously with throttles wide open, the Spitfires of 234 Squadron are guided south-east. December 2002 news March 2003 Inside the aircraft, sweating despite the chill of altitude, pilots scan the horizon. Over May 2003 the Sussex coast, the Spitfires suddenly find themselves engaged by Messerschmitt Ancient timbers July 2003 109s. For the next 30 minutes a desperate struggle takes place, eventually stretching found near South September from Beachy Head to Romney in Kent, that ends only when ammunition and fuel are Yorkshire's oldest 2003 expended. church November 2003 January 2004 Pilot Officer William Scotty Gordon of Banffshire, aged 20, never returned to Middle March 2004 Mapping the Forest Wallop. His Spitfire X4036 was hit almost immediately, burying itself in Hadlow Down, May 2004 of Dean East Sussex. An RAF recovery team probed the smoking crater, collected any salvage, July 2004 made the area good and recovered Gordons remains. September Stonehenge Public 2004 Inquiry On the same day a further 17 British fighters and six aircrew were lost: almost 3,000 November 2004 British and German aircraft were destroyed over and around the UK in the Battle of Jan/Feb 2005 Education Awards Britain alone. By the end of the war, after the arrival of the US Army Air Forces in 1942, Mar/Apr 2005 the total had risen to over 11,000 . Some 100,000 aircrew had been killed. May/Jun 2005 New Light on Jul/Aug 2005 Roman Rampart The death of Scotty Gordon, then, was unremarkable for the time. What did excite the Sep/Oct 2005 press, however, 63 years after Gordon was buried in Mortlach churchyard watched by Nov/Dec 2005 his parents and two sisters, was the discovery of more human remains. In Brief Jan/Feb 2006 Mar/Apr 2006 Having searched unsuccessfully in 1974, on 31 May 2003 aviation archaeologists found May/Jun 2006 features not only the plane, but also tattered pieces of uniform and human bone. Few familiar Jul/Aug 2006 with the air war were surprised. Recovery teamsoften civilian contractors, lacking Sep/Oct 2006 Who Owns Our equipment and timeworked under intense pressure in the face of unrelenting aircraft Nov/Dec 2006 Dead? Jan/Feb 2007 Vince Holyoak and losses. High speed crashes, often accompanied by fire or explosions, hindered identification of bodies. Mar/Apr 2007 Andy Saunders May/Jun 2007 debate plane Jul/Aug 2007 The law stipulated that 7 lb (3 kg) was needed to establish a body. The common belief crashes that coffins were weighted to appear full may have been all too true. Though not widely Sep/Oct 2007 Nov/Dec 2007 Corroded In Action reported, small pieces of bone can be found today at plane crash sites, even when Jan/Feb 2008 aircrew have graves. Take the Spitfire excavated for Time Team in France. Pilot Flight Excavating plane Mar/Apr 2008 Sergeant Klipsch had been buried nearby: but it was euphemistically remarked in a crash sites can May/Jun 2008 magazine article about the dig that it was obvious somebody had died. bring special Jul/Aug 2008 rewards Sep/Oct 2008 Outraged Nov/Dec 2008 Archaeology At Sea Jan/Feb 2009 Behind such unfortunate incidents, however, lurks a much more disturbing story: that George Lambrick Mar/Apr 2009 of the missing. goes to sea May/Jun 2009 Jul/Aug 2009 By 1950 the RAFs Missing Research and Enquiry Service had located almost half the Heathrow Today, Sep/Oct 2009 40,000 aircrew posted missing over north-west Europe during World War II (1939-45). Nov/Dec 2009 Tomorrow The In 1953 Her Majesty the Queen inaugurated the memorial to the missing at World

1 of 4

16/12/2010 16:58

British Archaeology 75, March 2004

http://www.britarch.ac.uk/ba/ba75/feat1.shtml

Mike Pitts finds dramatic archaeology at Heathrow

Runnymede, on which the names of 20,466 aircrew of the British Commonwealth and Empire were commemorated. They have no known graves.

For the British Government, this ended the matter. In 1969, however, the film The Battle of Britain fuelled growing nostalgia. Relics of the air war, the remains of wrecks Home and Heritage that had littered the countryside, could still be found. Lynne Walker describes a battle Like 19th century barrow diggers, throughout the 1970s loose affiliations of enthusiasts CBA Briefing won to preserve competed in a mad scramble for the best artefacts. Virtually every accessible Battle of local homes Britain site was picked over, many being investigated two or even three times. Attention Fieldwork then turned to sites from later in the war, and recently has concentrated on using more CBA Network Yorkshire's Holy modern survey and recovery techniques to re-examine some which had previously Conferences Secret defied excavation. Courses & Jan Harding and lectures Ben Johnson reflect Inevitably human remains were found. Enthusiasts often relied on local knowledge, with Grants & awards on 10 years little idea as to what type of aircraft a site contained, let alone its identity. In 1972 Pilot Noticeboard fieldwork Officer George Drake became the first missing Battle of Britain casualty to be recovered. Leutnant Werner Knittel followed in 1973, then Gefrieter Richard Riedel and CBA Bone People Flying Officer Franciszek Gruszka (1974), Oberfeldwebel Karl Herzog, Obergefrieter Terry OConnors Herbert Schilling and Sgt Edward Egan (1976) and Oberltnt Ekkehard Schelcher (1979). homepage quick guide to recognising human Each find was greeted by an outraged press. The Ministry of Defence (MoD) issued bones revised guidance, but a further three aircrew were discovered in 1979, and two in 1980.

Jan/Feb 2010 Mar/Apr 2010 May/Jun 2010 Jul/Aug 2010 Sep/Oct 2010 Nov/Dec 2010

letters

Piltdown, Orwell, Roman villas and hetrosexual values

The only answer, it seemed, was legislation. The Protection of Military Remains Act came into force in September 1986. Meanwhile six more bodies had come to light. Ltnt Helmut Strobl was found just days before the new legislation, from a site already excavated twice before. Earlier finds had included Strobls parachute harness buckle and Iron Cross, but reportedly, no human remains. However, at the third investigation bones and Strobls identity disk were recovered: underlining the need for control, they had been buried in a plastic carrier bag. Since 1986 eleven more missing aircrew have been recovered. Three were excavated accidentally, when licences were issued for the wrong aircraft. The most disturbing cases are two found by an enthusiast angered by the MoDs refusal to grant licences.

opinion

Sue Beasley is not impressed by treasure

His first dig was at a crash site at Chilham, Kent, long suspected to have been that of Sgt Gilders, missing in action in 1941. It was common knowledge locally that the aircraft contained a body; the landowner had vetoed excavation. When ownership Neil Mortimer fails changed, the enthusiast, with the consent of both the new owner and the Gilders psychic link-up with family, asked the MoD to excavate. They declined, saying there was no proof that the Medieval Wales crash was Sgt Gilders, nor certainty of recovering remains. Yet when the enthusiast applied to excavate the site himself, he was refused on the grounds that the site might books contain human remains. Exasperated, he conducted an excavation. He found Gilders remains, and proof of identity. He was then tried under the Military Remains Act, Britain BC. Life in receiving an absolute discharge. Britain & Ireland before the Romans Abandoned by Francis Pryor

spoilheap

In the second case the same man excavated a crash site near Lydd, Kent, from which the pilot had not been recovered in 1940. A small excavation in 1973 was thought to have found human remains. The landowner and the pilots family gave their consent, and the enthusiast excavated without even applying for a licence. Curiously, it seemed Anglo-Saxon Crafts that the aircraft had already been fully excavated. Soon the enthusiast was again by Kevin Leahy charged under the Military Remains Act. However, it was discovered that an RAF team had re-excavated the site shortly after the original 1973 recovery, and had found human remains. With the identity of the wreck unproven, these had been buried as Viking Weapons & unknown. When this came to light the MoD dropped charges. Warfare by J Kim Siddorn Pompeii. A Novel by Robert Harris This enthusiast had previously excavated a third site without permission, so the MoD may have felt compelled to take action. However, their apparent intransigence concerning the missing should also be considered. In 1998 war historian Dilip Sarkar identified seven Battle of Britain crash sites thought to contain missing crew. One, beneath a disused warehouse in Gravesend, Kent had already been the subject of an illegal recovery attempt. Sarkar reported that only once, in 1990, had the MoD acted on the wishes of a pilots family and carried out a recovery: this appeared to be due solely The Port of Medieval London by to the intervention of the Prince of Wales. Gustav Milne Glastonbury: Myth & Archaeology by Philip Rahtz & Lorna Watts

2 of 4

16/12/2010 16:58

British Archaeology 75, March 2004

http://www.britarch.ac.uk/ba/ba75/feat1.shtml

The City by the Pool by Michael J Jones, David Stocker & Alan Vince Revealing the Buried Past by Chris Gaffney & John Gater Essex Past & Present by Essex County Council Seven Ages of Britain by Justin Pollard

Why then, even when requested to do so by relatives, has the MoD declined to recover the remains of missing aircrew? It points out that the Protection of Military Remains Act does not provide for relatives wishes. It cites historical precedence, saying that the battlefield grave is an honourable British tradition. After the Great War (1914-18), despite families entreaties, the Empires dead were left where they were, for reasons of cost and equality. Repatriating only identified remains, it was argued, would discriminate against the families of the hundreds of thousands in graves marked only Known unto God or listed as missing. During WWII this policy continued, except for service personnel killed within the UK, whose relatives could have their loved ones returned. Flag-draped coffins awaiting collection at provincial railway stations became all too common. However time, confusion over wreck identities and salvage difficulties sometimes led to sites being abandoned, and connections between missing casualties and wrecks were lost. It was different elsewhere. In 1920 the French government caved in to pressure and allowed relatives to reclaim their war dead, at state expense. Within two years, in a remarkable exercise in logistics, some 300,000 fallen had been exhumed and returned to their home towns.

The Complete The British Governments attitude contrasts even more sharply with that of the United Roman Army by Adrian Goldsworthy States, which from World War I has been committed to repatriating its war dead. The RAFs Missing Research and Enquiry Unit ceased work in the 1950s. The US Armys Central Identification Laboratory, Hawaii is searching now. Consider this recent case. Tracks & Traces: the Archaeology of the Channel Tunnel Recovered by Rail Link In March 1945, B17 Flying Fortress Tondalayo of the 858th Bombardment Squadron, VIIIth US Army Air Forces was shot at while returning to base at Cheddington, Suffolk. CBA update Some official records note Tondalayo was caught by a night intruder, but investigation showed this was what we would call a blue on blue incident: nervous British tv in ba anti-aircraft gunners thought it was Luftwaffe. Pilot Lieutenant Colonel Earle J Aber and co-pilot 2nd Lt Maurice J Harper signalled the emergency, and held Tondalayo long Angela Pinccini enough for nine crew to bail out. She then cartwheeled into the sea off the River Stour, introduces a new Essex. Salvage recovered nothing of Harper, and of Aber, only an arm and hand. review feature. In 1990, for reasons that are not clear, the MoD approved an excavation at which, it was reported, flying clothing was recovered and human remains were exposed on a sand bank at low tide. Concerned, the Midlands Aircraft Recovery Group, amateur but highly experienced aviation archaeologists, asked the MoD to effect a recovery or allow them to do it themselves. The Ministry refused both. The US Mortuary Affairs team, prompted by lobbying, visited in 1998. Two years later, with the help of the East Essex Aviation Museum and a local marine contractor, they made a full recovery, finding bones and Aber and Harpers wallets. Those remains not identified by DNA testing were buried with full military honours in a joint grave at Arlington national cemetery. Abers bones were deposited in his existing grave at Maddingley US military cemetery, Cambridge, and Harpers returned home to Birmingham, Alabama.

ISSN 1357-4442 Editor Mike Pitts

Heartfelt pleas

Aber and Harper would still be in the sea, but for the intervention of the US military. The United States is not alone in its enlightened approach. Having signed the 1949 Geneva Convention on Humanitarian War Legislation, the Netherlands committed itself to recovering, identifying and, where requested by relatives, repatriating aircrew remains. Gerrit Zwanenberg, a senior officer of the Royal Netherlands Air Forces Aircraft Evacuation Unit, was awarded an MBE. The wishes of the families of missing British and Commonwealth air crews have greater recognition in the Netherlands than they have ever found in Westminster. Perhaps less surprisingly, the MoDs policy of non-interference extends to ordnance. As recently as October 2002 an area of Sunderland had to be evacuated when workmen uncovered an unexploded Luftwaffe 453 kg bomb. Disturbance had set the fuse, and it took an Explosive Ordnance Disposal team almost two days to make the bomb safe. The MoD states it has no obligations to seek out and clear those crash sites known still to contain unexploded bombs, and that the safest policy is to leave them alone. This is

3 of 4

16/12/2010 16:58

British Archaeology 75, March 2004

http://www.britarch.ac.uk/ba/ba75/feat1.shtml

perhaps fine so long as landowners and developers are aware of their presence. Families, veterans, enthusiasts and the public have widely differing views on what should be done about air wrecks. Nobody could disagree that the MoD has had an extremely difficult task. Despite an honourable attempt at control, there are clearly problems. The wishes of the families of the deceased should take precedence: whatever the legal obligations, the case for doing nothing in the face of heartfelt pleas appears less and less convincing. Holyoak is a professional archaeologist

4 of 4

16/12/2010 16:58

Você também pode gostar

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- FOWW Battle Mode v10 DownloadDocumento9 páginasFOWW Battle Mode v10 DownloadMeriadec ValyAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- 2 by 2 Napoleonic House RulesDocumento26 páginas2 by 2 Napoleonic House RuleschalimacAinda não há avaliações

- Navedtra 14014 AirmanDocumento384 páginasNavedtra 14014 AirmanSomeone You Know100% (1)

- TotalFilmAnnual PDFDocumento148 páginasTotalFilmAnnual PDFAlberto gf gf100% (1)

- Greece and Albanian Question-Extrait From Hellas and Balkan WarsDocumento26 páginasGreece and Albanian Question-Extrait From Hellas and Balkan Warsherodot_25882100% (9)

- RECLASSIFICATION OF MOS 91B ASI R4 TO 91S (MILPER Message10-225)Documento2 páginasRECLASSIFICATION OF MOS 91B ASI R4 TO 91S (MILPER Message10-225)Tim DelaneyAinda não há avaliações

- Indochine IABSMDocumento6 páginasIndochine IABSMjpAinda não há avaliações

- Bersaglieri support optionsDocumento1 páginaBersaglieri support optionsXijun LiewAinda não há avaliações

- Paramed 2022Documento99 páginasParamed 2022Coco C'toutAinda não há avaliações

- UntitledDocumento434 páginasUntitledcatherinne moraAinda não há avaliações

- The Iran-Contra Affair: A Political Scandal Revealed: Republic of The PhilippinesDocumento30 páginasThe Iran-Contra Affair: A Political Scandal Revealed: Republic of The Philippinesnah ko ra tanAinda não há avaliações

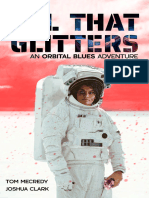

- Orbital Blues - SMP - All That Glitters (OEF, 2022-11-02)Documento60 páginasOrbital Blues - SMP - All That Glitters (OEF, 2022-11-02)Sergio CoteloAinda não há avaliações

- Chinese Revolution PDFDocumento4 páginasChinese Revolution PDFANAAinda não há avaliações

- Desw016en (Web)Documento340 páginasDesw016en (Web)remus_remus22100% (1)

- Warhammer 40k - Army List - Datasheet - Carnodon (2018)Documento1 páginaWarhammer 40k - Army List - Datasheet - Carnodon (2018)Знайомий ХтоAinda não há avaliações

- Marvel - Ultimate Alliance 2 Cheats, Codes, Unlockables - PlayStation 3 - IGNDocumento7 páginasMarvel - Ultimate Alliance 2 Cheats, Codes, Unlockables - PlayStation 3 - IGNABernardo VinasAinda não há avaliações

- The Shutters by Ahmed BouananiDocumento118 páginasThe Shutters by Ahmed BouananiPranay DewaniAinda não há avaliações

- National Self DeterminationDocumento13 páginasNational Self DeterminationlazyEAinda não há avaliações

- Owners Manual CB Unicorn 160 HindiDocumento101 páginasOwners Manual CB Unicorn 160 HindircpawarAinda não há avaliações

- Arnold's SacrificeDocumento2 páginasArnold's SacrificeAlmira ĆosićAinda não há avaliações

- Comparison Between The Political Situations in Harry Potter & WW2Documento3 páginasComparison Between The Political Situations in Harry Potter & WW2evaAinda não há avaliações

- Mask or Die in The LRPF Battlespace of 2040 - by John AntalDocumento3 páginasMask or Die in The LRPF Battlespace of 2040 - by John AntalEdwin TaberAinda não há avaliações

- Wilbur Smith Books CollectionDocumento3 páginasWilbur Smith Books CollectionAamirShabbir100% (2)

- Balbhadra KunwarDocumento3 páginasBalbhadra Kunwarprajwal khanalAinda não há avaliações

- Battle Royal Thesis StatementDocumento7 páginasBattle Royal Thesis Statementvaj0demok1w2100% (2)

- TRAGEDY of East PakistanDocumento31 páginasTRAGEDY of East Pakistanliza kamranAinda não há avaliações

- AVT International Schools Aug 20th-24th - 2018Documento17 páginasAVT International Schools Aug 20th-24th - 2018An ThienAinda não há avaliações

- Gregorio Del Pilar (Goyo) : November 14, 1875-December 2, 1899Documento34 páginasGregorio Del Pilar (Goyo) : November 14, 1875-December 2, 1899Keziah AliwanagAinda não há avaliações

- Genaral 2016 22 EnglishDocumento62 páginasGenaral 2016 22 EnglishbibahabondhonitAinda não há avaliações

- Kingdoms of Camelot GuideDocumento11 páginasKingdoms of Camelot Guidedannys2sAinda não há avaliações