Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Fuzzy Nominating Technique

Enviado por

Prof. Samirranjan AdhikariDireitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Fuzzy Nominating Technique

Enviado por

Prof. Samirranjan AdhikariDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

A FUZZY NOMINATING TECHNIQUE IN CLASS ROOM SITUATION

Dr. Samirranjan Adhikari

1.1

Introduction:

1.1.1 Nominating Technique and Sociometry In nominating technique, each person names or nominates other persons, events, objects, subject matter, which is perceived as fitting into certain categories or situations. The technique is commonly applied for studying social choices and rejections. Sociometry is one type of nominating technique. The word sociometry stems from the Latin socius, meaning social and the Latin metrum, meaning measure. As these roots imply, sociometry is a way of measuring the degree of social relatedness among people in a group. Jacob Levy Moreno has coined the term sociometry. Sociometry was developed by Jacob L. Moreno (1934, 1960) in the 1930s and became closely associated with small group research and a focus on interpersonal choices. Sociometry may be broadly defined as a method of discovering and evaluating group structure, social status and personality traits through measuring the acceptance or rejection between individuals in a group. A useful working definition of sociometry is that it is a methodology for tracking the energy vectors of interpersonal relationships in a group. It shows the patterns of how individuals associate

Assistant Professor of Psychology, Shimurali Sachinandan College of Education, Shimurali, Nadia, West Bengal, India, E-mail samirranjanadhikari@gmail.com

with each other when motivating together as a group toward a specified end or goal (Criswell in Moreno, 1960). Moreno defined sociometry as the mathematical study of psychological properties of populations, the experimental technique of and the results obtained by application of quantitative methods (Moreno, 1953). Thus, it is a technique of evaluating interpersonal relationship in a group. Stanley & Hopkins (1972) have defined Sociometry as the study of interrelationship among members of a group, that is, its social structure: how each individual is perceived by the group. With the help of sociometric technique the data relating to the choice, communication and interaction patterns of individuals in a group are gathered and analyzed (Kerlinger, 1973, 1986). Moreno conducted the first long-range sociometric study from 1932-38 at the New York State Training School for Girls in Hudson, New York. Moreno used sociometric techniques to assign residents to various residential cottages. He found that assignments based on sociometry substantially reduced the number of runaways from the facility (Moreno, 1953). In settings including other schools, the military, therapy groups, and business corporations Moreno and others have conducted many studies that are more sociometric. Measurement of social and emotional relatedness can be useful not only in the context of assessment of behaviour within a group, but also for interventions to bring about positive change in the desired direction and for determining the extent of change takes place as a result of these interventions. As sociometry allows the group to see itself objectively and to analyze its own dynamics, so, for a work group, it can be a powerful tool for reducing conflict and improving interpersonal communication. It also acts as a

powerful tool for assessing dynamics and development in groups devoted to therapy or training. Whenever a group of individuals come forward with a common mission, they make choices where to sit or stand; choices about who is perceived as friendly and who not, who is central to the group, who is rejected and who is isolated. Sociometry is because individuals make choices in interpersonal relationships. Moreno says, Choices are fundamental facts in all ongoing human relations, choices of people and choices of things. It is immaterial whether the chooser knows the motivations or not it is

immaterial whether the choices are inarticulate or highly expressive, whether rational or irrational. They do not require any special justification as long as they are spontaneous and true to the self of the chooser. They are facts of the first existential order. (Moreno, 1953, p. 720). 1.1.2 Sociometric Criteria There are always some bases or criteria in choice making process. The criteria may be subjective, such as an intuitive feeling of liking or disliking a person on first impression; these also may be more objective and conscious, such as knowing that a person does or does not have certain skills needed for the group task. When members of a group are asked to choose others in the group based on specific criteria, everyone in the group can make choices and describe why the choices were made. From these choices a description emerges of the networks inside the group. A drawing, like a map, of those networks is called a sociogram. The data for the sociogram may also be displayed as a table or matrix of each members choices. Such a table is called a sociomatrix.

1.1.3 Some Principles of Criterion Selection a) b) The criterion should be as simply stated and as straightforward as possible. The respondents should have some actual experience in reference to the criterion, whether ex post facto or present, otherwise the questions will not arouse any significant response. c) The criterion should be specific rather than general or vague. Vaguely defined criteria evoke vague responses. d) e) When possible, the criterion should be actual rather than hypothetical. A criterion is more powerful if it is one that has a potential for being acted upon. For example, for incoming college freshmen the question Whom would you choose as a roommate for the year? has more potential of being acted upon than the question Whom do you trust? f) Moreno points out that the ideal criterion is one that helps further the lifegoal of the subject. Helping a college freshman select an appropriate roommate is an example of a sociometric test that is in accord with the life-goal of the subject. g) As a rule questions should be future oriented, imply how the results are to be used, and specify the boundaries of the group (Hale, 1985). h) And last, but not least, the criteria should be designed to keep the level of risk for the group appropriate to the groups cohesion and stage of development. 1.1.4 Measurement Inerrancy

However, sociometry is open to several common problems. Sociometric mapping assumes, of course, that individuals respond accurately to sociometric surveys or can be assessed accurately through observation. It tends not to record subconscious or illicit relationships. It may be biased toward recording attractions rather than dislikes because subjects more easily reveal the former. It is best when subjective sociometric responses can be validated through external objective measures. 1.1.5 Small Group Size Sociometric diagramming becomes unwieldy and difficult for readers to interpret for very large groups. In addition, sociometric techniques may be biased in larger groups since subjects tend to confine their choices to their own class range. 1.1.6 Group Dynamics A direction of the new behavioural science is toward building it as a compact theoretical and methodological science of human groups. As the most active and growing scholarly interest is called, much of the field of group dynamics is pieced together from the techniques of quantitative studies such as: a) b) c) d) the interview, the questionnaire, the controlled observation, the test and scale, and so on.

1.1.7 Cluster Analysis Cluster analysis, also called segmentation analysis or taxonomy analysis, is a way to create groups of objects, or clusters, in such a way that the profiles of objects in the

same cluster are very similar and the profiles of objects in different clusters are quite distinct. Cluster analysis can be performed on many different types of data sets. For example, a data set might contain a number of observations of subjects in a study where each observation contains a set of variables. Many different fields of study, such as engineering, zoology, medicine, linguistics, anthropology, psychology, and marketing, have contributed to the development of clustering techniques and the application of such techniques. For example, cluster analysis can help in creating balanced treatment and control groups for a designed study. If you find that each cluster contains roughly equal numbers of treatment and control subjects, then statistical differences found between the groups can be attributed to the experiment and not to any initial difference between the groups. Hierarchical clustering is a way to investigate grouping in your data, simultaneously over a variety of scales, by creating a cluster tree. The tree is not a single set of clusters, but rather a multilevel hierarchy, where clusters at one level are joined as clusters at the next higher level. This allows you to decide what level or scale of clustering is most appropriate in your application. The following sections explore the hierarchical clustering features in the Statistics Toolbox: 1.1.8 Validity of Sociometry Does sociometry really measure something useful? Jane Mouton, Robert Blake and Benjamin Fruchter reviewed the early applications of sociometry and concluded that the number of sociometric choices do tend to predict such performance criteria as

productivity, combat effectiveness, training ability, and leadership.

An inverse

relationship also holds: the numbers of sociometric choices received are negatively correlated with undesirable aspects of behaviour such as accident-proneness, sick bay attendance and frequency of disciplinary charges (Mouton, Blake, and Fruchter in Moreno, 1960). One study found a significant positive correlation between group sociometric cohesion and field performance of small military combat units (Goodacre and Daniel in Moreno, 1960). Sociometric ratings by co-workers for desirability as work partners and other job related activities correlate with positive attitudes toward work and with quality and quantity of performance on the job (Springer, 1953; Van Zelst, 1951). Accident proneness is inversely correlated with sociometric choices received. (Speroff, and Kerr, 1952; Fuller, and Baune, 1951; Zeleny, 1947) Consistent with these findings about safety are studies in military settings which show that flight accidents, frequency of sick bay attendance, and number of disciplinary offences are negatively related with the number of sociometric choices received when the criterion measures a positive aspect of behaviour (Zeleny, 1947; French, 1951) A study of leadership showed that when leaders were chosen by sociometric procedures, their groups were more efficient than when members not seen as leaders were assigned that role (Rock, and Hay, 1953) A study of navy pilots suggested that low morale and cliques may result when the official leader is not a sociometric star (Jenkins, John G. in Moreno, 1960 pp. 560 - 567).

A study of choices of playmates in fourth-grade children showed a high correlation between the choices children made on the sociometric test and the choices children made in actual play (Byrd, 1946). Bion (1959) observed two distinct groupings within the structure of therapy groups: a work group where group members acted as if they were in tune with the group's goal, and the basic assumption group where group members acted as if they were in the group for some other purpose. He identified three assumptions as uniting factors for group members in relationship to the group leader. He termed these the dependency assumption, the fight-flight assumption, and the pairing assumption. He noticed subgroupings forming around these. Schein (1986) noticed that groups formed for purposes other than the immediate task at hand. He identified that it is precisely because an individual brings multiple other group identities into any group - family, occupation, neighbourhood, friendship groups, prior employers, cultural experiences and so on - that he or she experiences new situations with anxiety. The anxiety is present before new configurations, new identities, and new associations are built. Williams (1994) comments, appropriate sociometric interventions can extend systems definitions of themselves and allow room for change. David Krackhardt and Jeffrey Hanson (1993) in the Harvard Business Review write about the company behind the chart, and affirm the notion that much of the real work of the company happens despite the formal organisation structure. These networks can cut through formal reporting procedures to jump start stalled initiatives and meet extraordinary deadlines. But informal networks can just as easily sabotage companies best laid plans by blocking

communication and fomenting opposition to change, unless managers know how to identify and direct them. In one instance Hoffman et al (1992) used the sociometric data to help work groups diagnose their own problems and to document the effectiveness of the intervention 1.2 Statement of the Problem: The researcher tried to understand the group belonging to M.P.Ed. Part 1 students by revealing interrelationship existing among the individuals making up this group and dynamics of motivations expressed through involvement of group members individually in between and in relation to symbol of the group. The title of the project was stated as Fuzzy Nominating Technique as Applied to M.P.Ed. Students of the Department of Physical Education, K.U.. 1.3 Purpose of the Study: a. To identify the characteristics or qualities of an individual by using the technique of sociometry, in the programme of Physical Education before assigning specific responsibility. b. It will be a help for a Physical Education teacher or coaches to understand the students or athletes under his care. c. It will help to construct and reconstruct groups and bring about a social readjustment in the direction of a more free happy and productive life. 2.1 Objective of the Present Study: From the survey of allied literature, we may conclude that sociometry is a powerful and effective technique to study the group structure. It provides a prima-facie

picture of the group structure and from that picture we can launch an in-depth study to detect the actual problem (if there any) to formulate a proper counselling and guidance programme. Traditionally in sociometry, the members of a group are asked to put their multiple choices, but all choices carry equal preferences (i.e. 1); also, some times multiple preferences are asked in ordinal numbers. In the present study, fuzzy logic is introduced in sociometry. We in the present study also asked the members of a group to put multiple choices (five) in accordance with their preferences in ordinal numbers and the preference values are transformed into fuzzy numbers. For further treatment of the data, these fuzzy numbers are taken into consideration. It is supposed that this procedure would increase the sensitivity of sociometric technique. 2.2 Participants The participants were thirty-one students of a post graduate class (M. P. Ed.: part - I) of the Department of Physical Education, University of Kalyani, Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal, India. 2.3 Measure A sociometric test was administered. The instruction (criteria) was Write five names (in order of your preference) of your classmates with whom you would like to go for Physical Education picnic. Psychological experiments have shown that human beings cannot simultaneously compare more than seven objects (plus or minus two) (Miller, 1956). This is the rational of considering five alternatives in this study. 2.4 Procedure

10

2.4.1 Construction of Preference Matrix:For ethical purpose, we did not disclose the name of the members of the group and so not to disclose the nominating pattern of the members instead of writing their names members of the group were symbolized by numbers. By tabulating the value of nomination in order of preference (1 to 5), as exercised by an individual member a Preference Matrix was formed which is shown in table-1. A row of the Preference Matrix represents the preference exercised by an individual member and a column represents the preference received by an individual member. The blank cells of Preference Matrix were supposed to contain integers greater than 5. 2.4.2 Construction of Fuzzy Preference Matrix:A Fuzzy Preference Matrix was formed which is shown in table-2. In course of converting a preference value to a fuzzy number, following membership function was used: a) b) c) (x) = 1; for x < 1 x 5

(x) = (5 - x) / (5 -1); for 1 (x) = 0;

for x > 5

2.4.3 Determination of Fuzzy Preference Index (FPI):Column total was calculated to determine FPI of each individual member of the group. To do so Fuzzy Arithmetic Technique was applied and here the weighted sum of fuzzy numbers was taken. The weight here was 1/ n, where n = number of members of the group (here 31). 2.4.4 Determination of Star, Popular, Isolate and Neglected:Star, Popular, Isolates and Neglected are defined as follows:

11

a)

Popular In a group, there are persons who are liked by many members of

the group. Such persons are very popular in the group. FPI is the measure of popularity. The members of the group who receive more FPI are popular in the group. b) the group. c) Isolates In a group, there are members who do not like any member of Star The individual member who receives the highest FPI is the star in

the group nor are themselves liked by any member of the group. Such persons are called isolates. A member who does not receive even a single FPI is an isolate. d) Neglected In a group, there are persons who like others bur are they not

so liked by others. Such persons are called neglected members in the group. The individual who receive fewer FPI is a neglected one. From table containing Fuzzy Preference Index (FPI) Star, Popular, Isolates and Neglected members of the group were chalked out. 2.4.5 Diagonal cells of the Fuzzy Preference Matrix:Diagonals of the matrix were filled up by one (1). 2.4.6 Determination of Subgroup and Clique by Cluster Analysis:Subgroup and Clique refers to a situation in which a number of individuals choose each other, but give relatively few preferences out their sub-group. To determine subgroup and clique cluster analysis was done with Fuzzy Preference Matrix. To do cluster analysis Words method with Squared Euclidean Distance as proximity index was adopted. To do cluster analysis preferences exercised by a member were considered as his/her vector. Cluster analysis was done with the help of SPSS 10.0 software.

12

3.1 3.1.1

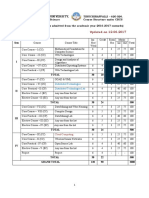

Results and Discussions Preference Matrix Table 1 presented the sociometric matrix and had the names of students as the

chooser and the chosen. The choices of all 31 students were entered in the sociometric matrix. Each student made five choices in order of preference.

From the table it could be observe that the student 13 had received the highest first preference (13). The student 30 had received the highest second preference (12). It could also be seen the lowest preference was obtained by four students -1, - 9, -14, - 23.

13

3.1.2 Fuzzy Preference Matrix Table 2 indicated the fuzzy preference index of each individual member of the group. Column total was calculated to determine the FPI. From FPIs star, popular, isolates, neglected, members of the groups were chalked about.

The student - 13 received the highest FPI (0.28) was the star in the group. The number of the group who received more FPI were as follows student -3, - 8, -15, -18, - 20, -25, -26, 30 these were the students who were liked by many members of the groups and considered to be very popular. The neglected member in the group those who received few FPI were found to be sixteen in numbers , viz. Student -2, - 4, - 5, -6, -7, -10, -11, 16, -17, -19, -21, -22, -24, -27, -29, -31. These were the students considered to be

14

neglected in group: those who liked others but they were not liked by other members in the group. The isolate members who did not receive even a single FPI were the student 1,- 5,- 9,- 14 and - 23. They were the members who were not liked by any member of the group. Following were the results: Star student -13 (0.28) Popular student - 3 (0.13), -8 (0.12), -15(0.13), -18(0.11), -20(0.21),- 25(0.17), 26(0.14), -28(0.18), -30(0.23) Isolates Student -1, -5, -9, -14, - 23 Neglected Student -2, -4, -5, -6, -7, -10, -11, -16, -17, -19, -21, -22, -24, -27, -29 and -31 3.1.3 Cluster Analysis: Subgroup and Clique Result of the cluster analysis was presented in figure 1. Figure 1 showed that there were two very distinct subgroups in the group under study. One subgroup was comprised of fourteen students 23, -26,-10,-4,-24,-29,-21,-31,-8,-28,-19,-27,-11 and -13, and the other subgroup was formed by seventeen students 15,-20,-17,-25, -9,-6,18,-12,-14,-7,-22,-2,-16,-3,-30, -1 and -5. There were several cliques within a subgroup. (i) a) b) c) d) e) In the first subgroup, the cliques were as follows: Student 13,-26,-10,-4 Student 24,-29 Student 21, 31 Student 8,-28,-19,-27 Student 11,-23

15

Figure 1: Showing Dendrogram using Ward Method

(ii) f) g)

In the second subgroup, the cliques are as follows: Student 15,-20,-17,-25,-9 Student 6,-18,-12,-14

16

h) i) j) 3.2

Student 7,-22 Student 2,-16 Student 3,-30,-1,-5

Conclusion: The results of the present study transpired that the group was not so

homogeneous, because there were many cliques in a subgroup. The investigator was acquainted with the group for several years. The results of the present study were in corroboration with the investigators personal experience about the structure of the group. In this study group cohesiveness was not assessed. However, it may conclude that the cohesiveness of the group was low. For comprehensive result enough deep study should be launched by considering external objective measure.

References:

Bion, W.R. (1959). Experiences in Groups. Tavistock Brandes, Ulrik, Patrick Kenis, Jorg Raab, Volker Schneider, and Dorothea Wagner (1999). Explorations into the visualization of policy networks. Journal of Theoretical Politics 11(1): 75-106. Degenne, A. and Forse, M. (1999). Introducing social networks. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. French, R. L.(1951). Sociometric Status and Individual Adjustment among Naval Recruits. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 46, 64 - 72.

17

Fuller, E. M., and H. A. Baune,H.A. (1951). Injury-Proneness and Adjustment in a Second Grade. Sociometry, 14, 210 225 Hale, A. E. (1985). Conducting Clinical Sociometric Explorations: A Manual. Roanoke, Virginia: Royal Publishing Company. Hoffman, C., Wilcox, L., Gomez, E. & Hollander, C. (1992). Applications in a Corporate Environment, Journal Sociometric of Group

Psychotherapy, Psychodrama & Sociometry, 45, 3-16. Kerlinger, F.N. (1973).Foundations of behavioural research. New

York:HoltRinehart and Winston, inc Kerlinger, F.N. (1986).Foundations of behavioural research. New

York:HoltRinehart and Winston, inc Krackhardt, D. and Hanson, J. (1993). Informal Networks: The Company behind the Chart. Harvard Business Review, July- August. Moreno, J. L. (1934, Revised edition 1953). Who Shall Survive? Beacon, NY: Beacon House. Moreno, J. L. (1960). The Sociometry Reader. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press. Rock, M. L. and Hay,E.N. (1953). Investigation of the Use of Tests as a Predictor of Leadership and Group Effectiveness in a Job Evaluation Situation. Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 109 - 119. Schein, E.H. (1986). Organisational Culture and Leadership, A Dynamic View, Jossey-Bass Publishers. Scott, J. (1992). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

18

Speroff, B., and Kerr, W. (1952). Steel Mill Hot Strip Accidents and Interpersonal Desirability Values. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 8, 8991. Springer, D.(1953). Ratings of Candidates for Promotion by Co-workers and Supervisors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 37, 347-351. Stanley, J.C. and Hopkins, K.D. (1972). Educational and psychological

measurement and evaluation. Englewood Cliff, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Van Zelst, R. H. (1951). Worker Popularity and Job Satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 4, 405 - 412). Wasserman, S. and Faust, K. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Zeleny, L. D. (1947). Selection of Compatible Flying Partners. American Journal of Sociology, 52, 424 - 431.

19

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalaya (KGBV) Scheme As Facilitator To Academic Motivation and Life Satisfaction of The Female LearnersDocumento220 páginasKasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalaya (KGBV) Scheme As Facilitator To Academic Motivation and Life Satisfaction of The Female LearnersProf. Samirranjan AdhikariAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Sensation Perception Thinking ImaginationDocumento8 páginasSensation Perception Thinking ImaginationProf. Samirranjan AdhikariAinda não há avaliações

- Ph.D. ThesisDocumento225 páginasPh.D. ThesisProf. Samirranjan AdhikariAinda não há avaliações

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Neuropsychology in EducationDocumento86 páginasNeuropsychology in EducationProf. Samirranjan AdhikariAinda não há avaliações

- Test AnxietyDocumento8 páginasTest AnxietyProf. Samirranjan AdhikariAinda não há avaliações

- Community Based RehabilitationDocumento61 páginasCommunity Based RehabilitationProf. Samirranjan Adhikari100% (1)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Educational PsychologyDocumento15 páginasEducational PsychologyProf. Samirranjan AdhikariAinda não há avaliações

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Fundamentals of Machine Learning 4341603Documento9 páginasFundamentals of Machine Learning 4341603Devam Rameshkumar RanaAinda não há avaliações

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Data Science Lab ManualDocumento40 páginasData Science Lab ManualmmrmathsiubdAinda não há avaliações

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Introduction To Data Analytics MCA-3282 Open Elective - 6 Sem B.Tech Topic - GroupingDocumento44 páginasIntroduction To Data Analytics MCA-3282 Open Elective - 6 Sem B.Tech Topic - GroupingAnandAinda não há avaliações

- Risk Analytics Data Driven Decisions Under Uncertainty RodriguezDocumento483 páginasRisk Analytics Data Driven Decisions Under Uncertainty RodriguezGeorgie MachaAinda não há avaliações

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- Data Mining Unit-IvDocumento34 páginasData Mining Unit-Ivlokeshappalaneni9Ainda não há avaliações

- Data Mining - Docx GhhdocxDocumento6 páginasData Mining - Docx GhhdocxSiddharth JainAinda não há avaliações

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Fuzzy TheoriesDocumento11 páginasFuzzy TheoriesÃh JáçkAinda não há avaliações

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Cluster Analysis - Market SegmentationDocumento5 páginasCluster Analysis - Market Segmentationnambi2rajanAinda não há avaliações

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- Scikit-Learn User Guide Release 0.19.dev0Documento2.133 páginasScikit-Learn User Guide Release 0.19.dev0h_romeu_rs100% (2)

- A Novel Framework For Smart Cyber Defence A Deep-Dive Into Deep Learning Attacks and DefencesDocumento22 páginasA Novel Framework For Smart Cyber Defence A Deep-Dive Into Deep Learning Attacks and DefencesnithyadheviAinda não há avaliações

- Unsupervised Learning Using Back Propagation in Neural NetworksDocumento4 páginasUnsupervised Learning Using Back Propagation in Neural NetworksPrince GurajenaAinda não há avaliações

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Vosviewer Manual: Nees Jan Van Eck and Ludo Waltman 31 August 2019Documento53 páginasVosviewer Manual: Nees Jan Van Eck and Ludo Waltman 31 August 2019faridAinda não há avaliações

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Unit #2 - Data Warehouse and Data MiningDocumento51 páginasUnit #2 - Data Warehouse and Data MiningTanveer Ahmed HakroAinda não há avaliações

- MSC Computer Science Updated On 12 06 2017 PDFDocumento33 páginasMSC Computer Science Updated On 12 06 2017 PDFB. Srini VasanAinda não há avaliações

- Fusionex ADA (Day2) v3 2022Documento109 páginasFusionex ADA (Day2) v3 2022izzudinrozAinda não há avaliações

- Cluster Analysis ClusteringDocumento6 páginasCluster Analysis Clustering17CSE97- VIKASHINI TPAinda não há avaliações

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Machine Learning For BeginnerDocumento31 páginasMachine Learning For Beginnernithin_vnAinda não há avaliações

- Multispectral and X-Ray Images For Characterization of Jatropha Curcas L. Seed QualityDocumento22 páginasMultispectral and X-Ray Images For Characterization of Jatropha Curcas L. Seed QualityFalner Joaquin Saldarriaga AvendañoAinda não há avaliações

- 03 Hierarchical ClusteringDocumento15 páginas03 Hierarchical ClusteringKushagra Bhatnagar100% (1)

- Hierarchical Afaan Oromoo News Text ClassificationDocumento11 páginasHierarchical Afaan Oromoo News Text ClassificationendaleAinda não há avaliações

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- STEP - Splunk Training and Enablement PlatformDocumento14 páginasSTEP - Splunk Training and Enablement PlatformbtbowmanAinda não há avaliações

- Pothole DetectionDocumento19 páginasPothole DetectionShivansh BansalAinda não há avaliações

- PlagiarismDocumento5 páginasPlagiarismrajigaddam 999Ainda não há avaliações

- AI Fellowship Syllabus LATAMDocumento17 páginasAI Fellowship Syllabus LATAMOscar Misael Peña VictorinoAinda não há avaliações

- Polygenic Scoring Accuracy Varies Across The Genetic Ancestry ContinuumDocumento25 páginasPolygenic Scoring Accuracy Varies Across The Genetic Ancestry ContinuumSergio VillicañaAinda não há avaliações

- Cluster AnalysisDocumento12 páginasCluster AnalysisUsman AliAinda não há avaliações

- Data Mining Methods Basics - RespDocumento33 páginasData Mining Methods Basics - RespIgorJalesAinda não há avaliações

- A Fuzzy Segmentation Study of Gastronomical ExperienceDocumento10 páginasA Fuzzy Segmentation Study of Gastronomical Experiencemariuxi_bruzza2513Ainda não há avaliações

- FonaDyn Handbook 2-4-9Documento70 páginasFonaDyn Handbook 2-4-9Viviana FlorezAinda não há avaliações

- Weka TutorialDocumento53 páginasWeka TutorialVikas BansalAinda não há avaliações