Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Report Writing 8

Enviado por

sajjad_naghdi241Descrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Report Writing 8

Enviado por

sajjad_naghdi241Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

How to write a Laboratory Report

Report writing is a generic skill that all engineers need. You have the opportunity to develop this skill through laboratory report writing during your degrees. Examples of well-written reports that received high assessments are something you could show potential employers. Before you can write a laboratory report you must complete the experiment(s). It is very important that enough time is spent reading and understanding the experiment notes (and references) before actually doing the experiment. It is much easier to report on an experiment that you did with a good understanding of what you were trying to do and why. Time spent preparing for a laboratory practical will always save you time in writing up the laboratory report. Students are required to keep a complete, intelligible record of their practical work. All measurements, observations, calculations and other relevant information must be recorded in a laboratory notebook. You may be required to append a copy of the relevant pages from your laboratory notes to a report at the time of submission. The layout of a report is not rigid, but a suitable format has evolved over many years. The layout below is a guide for good laboratory reports. However, there is no substitute for your own judgement in reporting your results. Developing your judgement should be one of your aims in your report writing. You will get further advice of what is expected in individual course modules from the lecturers and laboratory supervisors.

Typical Layout for a Laboratory Report

TITLE Your Name, Your Partner(s) Name(s) Date(s) of Experiment 1. Summary or Abstract This is not absolutely essential, but certainly desirable. This is usually the last section written, but should head the report. It should briefly explain what the experiment is about, and give a concise summary of the results and their significance. In the real world it will be the only section read by most readers, so it must be clear. 2. Introduction This contains the background to, and aims of the experiment or set of experiments. The background to the work needs to be clearly described in the context of existing knowledge (giving references if appropriate). For example, some experiments have historical significance and many engineering laboratory experiments will have a practical relevance that needs to be briefly described in the introduction. Others will be adequately introduced by a description of a physical phenomenon and why it is important. The introduction should normally be no more than 20% of the total report in length.

Dr C. Carliell-Marquet

Laboratory Report Writing Page 1

3.

Theory This section should include all theoretical relations that will be used to interpret your results in later sections.

4.

Methods Describe the experiment, produce and refer to figures of the experimental procedure and apparatus as necessary. List important apparatus. Each figure must be numbered and have an accompanying figure caption. Do not reproduce the laboratory manual/notes. Give a reference to these in your report as seems appropriate. You may like to attach a copy of the laboratory notes to the back of your report for future reference.

5.

Results This is where you put your data, without any significant analysis. Graphs and/or Tables should be labelled, and units and uncertainties always included. Raw data should not normally be put in an Appendix. You have your laboratory log book as evidence of your original measurements if these are ever required.

6.

Analysis of Results and the Discussion Analyse, interpret and discuss each result in some detail. This should include a sensible analysis of the random and systematic errors. Compare your results with theoretical expressions, known values and previous results of other researchers where appropriate. Differences between your results and the expected results or theory must be adequately explained, not just noted, e.g. where there is a predicted linear relationship in data, is this validated by your results? If not, what reasons can you give to explain this?

7.

Conclusions This is not just a rehash of the summary. Try to take an overview of the experiment, where you've reached and where further investigation might be warranted. The conclusions must give the implications of your findings, i.e. tell the reader what your findings mean, not just what they are. Avoid stock phrases like "The results agreed with theory within the limits of experimental error" this does not illustrate that you understand the experiment and your findings.

8.

Acknowledgements, if applicable Those who have contributed to the work deserve to be acknowledged.

9.

References Give full details of references referred to in your report. If you havent referred to a source in the report, even though you might have read it in order to understand something to do with the report, it is not a reference. e.g. 1. 2. R. Resnick, D. Halliday and K.S. Krane, (1992), Physics 4th ed. (Wiley: New York) p. 55. J.P. Gordon, H.J. Zeiger and C.H. Townes, "The maser - new type of microwave amplifier, frequency standard, and spectrometer", Phys. Rev. 18, 1264-1274 (1955).

Dr C. Carliell-Marquet

Laboratory Report Writing Page 2

10.

Appendices In a long report some material may need to be included which would affect its readability, e.g. a long derivation of an equation for which no adequate reference can be found, a listing of a computer program written to assist in analysis of data. These should be included as appendices. General Notes

(i)

The style of the report should be concise, written in the 3rd person, e.g. The experiment was done. rather than I did the experiment., and in the past tense. This is the style most appropriate to written reports in any scientific or technical environment. Your sentences should present ideas in a logical sequence. Do not give instructions, such as Connect A to B- rather write A was connected to B. Paragraphs should be used to introduce new topics. You are also expected to write legibly, with good grammar, and spell accurately. You should always proof read your laboratory reports. Where a report is short it is reasonable to combine two or more sections under one heading, e.g. Results and Discussion.

(ii)

Assessment

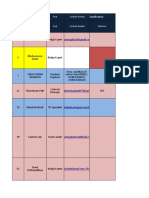

The following gives you an example of how laboratory reports would be assessed: Marks out of 10 0 marks 1 - 2 marks 3 - 4 marks Little of the set work was done, and that was incompletely and illegibly reported. Not much of the set work was done, and that was reported incompletely or illegibly. Much of the set work was done, but the report was unacceptable because it failed to compare experiment with theory or was incomplete or illegible or lacked proper treatment of uncertainties. Most of the set work was done. However the report revealed some gaps in the student's understanding, and/or missed obvious comparisons of experiment with theory, and/or was incomplete or illegible, and/or treatment of uncertainties was inadequate. Almost all of the set work was done, and the report indicated that the student understood what was going on, and successfully compared experiment with theory when requested, producing a complete and legible report. While meeting the requirements for 9 marks, the student showed real initiative, e.g. by making comparisons of experiment with theory which were not requested, by carefully investigating an unexpected result, by making comments which indicate real insight, or by producing an exemplary report.

5 - 7 marks

8 - 9 marks

10 marks

This document was adapted from: Guidelines for Laboratory Report Writing (September 2002). The Department of Physics (Division of Information and Communication Sciences), Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.

Dr C. Carliell-Marquet

Laboratory Report Writing Page 3

Você também pode gostar

- Full Report Exer 1Documento8 páginasFull Report Exer 1marinella100% (1)

- Diagnostic Test Practical Research 2Documento4 páginasDiagnostic Test Practical Research 2Lubeth Cabatu88% (8)

- Shapin Steven The Scientific Revolution PDFDocumento236 páginasShapin Steven The Scientific Revolution PDFJoshuaAinda não há avaliações

- 1final Project - Design of A Concrete Vibrating TableDocumento50 páginas1final Project - Design of A Concrete Vibrating Tablesajjad_naghdi241100% (2)

- 1-Introduction To Analytical ChemistryDocumento181 páginas1-Introduction To Analytical ChemistryFernando Dwi AgustiaAinda não há avaliações

- Chemistry Command WordsDocumento4 páginasChemistry Command WordsCh'ng Lee KeeAinda não há avaliações

- Mass Spectrometry Dry Lab CHM 1021Documento7 páginasMass Spectrometry Dry Lab CHM 1021himaAinda não há avaliações

- Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data AnalysisNo EverandEnzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism, and Data AnalysisNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)

- Gekko TutorialDocumento55 páginasGekko Tutorialsajjad_naghdi2410% (1)

- Specifying A Purpose and Research Questions or HypothesesDocumento27 páginasSpecifying A Purpose and Research Questions or HypothesesMohd Asyrullah100% (1)

- 10 Chemistry Annual Report 2016-17Documento56 páginas10 Chemistry Annual Report 2016-17Hussein KyhoieshAinda não há avaliações

- Green Nanotechnology Challenges and OpportunitiesDocumento33 páginasGreen Nanotechnology Challenges and Opportunitiespmurph100% (1)

- Gravimetric Analysis Very GoodDocumento24 páginasGravimetric Analysis Very Gooddhungelsubhash8154Ainda não há avaliações

- SOP Revised For Affiliated PG Colleges 28.01.2021Documento39 páginasSOP Revised For Affiliated PG Colleges 28.01.2021rahulAinda não há avaliações

- Green Chemistry: Principles and Practice: Paul Anastas and Nicolas EghbaliDocumento12 páginasGreen Chemistry: Principles and Practice: Paul Anastas and Nicolas EghbalifuatAinda não há avaliações

- Chemistry Laboratory I: Experiment 5: Determination of Nickel by Gravimetric AnalysisDocumento2 páginasChemistry Laboratory I: Experiment 5: Determination of Nickel by Gravimetric AnalysisCatherine Chan0% (1)

- The Role of Organic Reagents PDFDocumento16 páginasThe Role of Organic Reagents PDFLUIS XVAinda não há avaliações

- Sustainable Green Chemistry PDFDocumento129 páginasSustainable Green Chemistry PDFJaime BoteroAinda não há avaliações

- Observation Report: Analytical ChemistryDocumento8 páginasObservation Report: Analytical ChemistryLindsay BulgerAinda não há avaliações

- Aluminum HydroxideIIDocumento21 páginasAluminum HydroxideIIbayadmomoAinda não há avaliações

- Precipitation Titration 2015Documento22 páginasPrecipitation Titration 2015MaulidinaAinda não há avaliações

- Complexometric Titration of Zinc: An Analytical Chemistry Laboratory ExperimentDocumento1 páginaComplexometric Titration of Zinc: An Analytical Chemistry Laboratory ExperimentMuhammad Fatir100% (1)

- Julián Blasco, Antonio Tovar-Sánchez - Marine Analytical Chemistry-Springer (2022)Documento459 páginasJulián Blasco, Antonio Tovar-Sánchez - Marine Analytical Chemistry-Springer (2022)john SánchezAinda não há avaliações

- Porphyrins in Analytical ChemistryDocumento16 páginasPorphyrins in Analytical ChemistryEsteban ArayaAinda não há avaliações

- Potentiometric Titration of An Acid MixtureDocumento9 páginasPotentiometric Titration of An Acid MixtureRuth Danielle GasconAinda não há avaliações

- Nanomaterials: Boxuan Gu and David McquillingDocumento31 páginasNanomaterials: Boxuan Gu and David McquillingVenkata Ganesh GorlaAinda não há avaliações

- Determination of Chloride (CL) : Gargi Memorial Institute of TechnologyDocumento2 páginasDetermination of Chloride (CL) : Gargi Memorial Institute of TechnologyswapnilAinda não há avaliações

- Clinical Chemistry - Analytical Techniques, Reagent Preparation, and AutomationDocumento9 páginasClinical Chemistry - Analytical Techniques, Reagent Preparation, and Automationrosellae.Ainda não há avaliações

- SevenEasy - Cond - EN Mettler Toledo s30 PDFDocumento18 páginasSevenEasy - Cond - EN Mettler Toledo s30 PDFJAIRSAN1Ainda não há avaliações

- OxidationDocumento16 páginasOxidationCoralsimmerAinda não há avaliações

- Atomic Spectroscopy and Atomic Absorption SpectrosDocumento80 páginasAtomic Spectroscopy and Atomic Absorption SpectrosMuhammad Mustafa IjazAinda não há avaliações

- 8.3 Acid - Base Properties of Salt SolutionsDocumento14 páginas8.3 Acid - Base Properties of Salt Solutionskalyan555Ainda não há avaliações

- Analysis of Trace Metals in Honey Using Atomic Absorption Spectroscop-Power PointDocumento16 páginasAnalysis of Trace Metals in Honey Using Atomic Absorption Spectroscop-Power PointTANKO BAKOAinda não há avaliações

- NABL-161-doc-GUIDE For INTERNAL AUDIT AND MANAGEMENT REVIEW FOR LABORATORIES ISSUEDocumento26 páginasNABL-161-doc-GUIDE For INTERNAL AUDIT AND MANAGEMENT REVIEW FOR LABORATORIES ISSUEVishal Sharma50% (2)

- Lab Chemist Interview Part 1Documento32 páginasLab Chemist Interview Part 1Viona AndhivaAinda não há avaliações

- First Law of Thermodynamics : Exothermic and Endothermic Processes Energy Level Diagrams Heat and WorkDocumento18 páginasFirst Law of Thermodynamics : Exothermic and Endothermic Processes Energy Level Diagrams Heat and WorkFrances PaulineAinda não há avaliações

- Gattermann - Laboratory Methods of Organic ChemistryDocumento449 páginasGattermann - Laboratory Methods of Organic ChemistryGaurav DharAinda não há avaliações

- R Data Analysis Examples - Canonical Correlation AnalysisDocumento7 páginasR Data Analysis Examples - Canonical Correlation AnalysisFernando AndradeAinda não há avaliações

- Gravimetric Analysis and Precipitation - TitrationsDocumento34 páginasGravimetric Analysis and Precipitation - TitrationsElvinAinda não há avaliações

- Practical Analytical 1 ,,chemistryDocumento45 páginasPractical Analytical 1 ,,chemistryFadlin AdimAinda não há avaliações

- 7 FDD1622 D 01Documento6 páginas7 FDD1622 D 01dizismineAinda não há avaliações

- GravimetryDocumento18 páginasGravimetryFransiscaa HellenAinda não há avaliações

- Sample Questions - Chapter 15Documento6 páginasSample Questions - Chapter 15Rasel IslamAinda não há avaliações

- CH 3Documento54 páginasCH 3hagos dargoAinda não há avaliações

- Measuring PH CorrectlyDocumento33 páginasMeasuring PH CorrectlyAnonymous Z7Lx7q0RzAinda não há avaliações

- CHEM 400: Fundamentals of Analytical Chemistry 8th Edition by Skoog, West, Holler, CrouchDocumento17 páginasCHEM 400: Fundamentals of Analytical Chemistry 8th Edition by Skoog, West, Holler, CrouchJen MaramionAinda não há avaliações

- NAAC Indicator With AnnexuresDocumento40 páginasNAAC Indicator With AnnexuresNaveen KumarAinda não há avaliações

- DR Sulbha Kulkarni-1Documento48 páginasDR Sulbha Kulkarni-1api-20005351100% (1)

- HPLC Detectors: Adapted From: HPLC For Pharmaceutical Scientists by Y.Kazakevich and R. LobruttoDocumento7 páginasHPLC Detectors: Adapted From: HPLC For Pharmaceutical Scientists by Y.Kazakevich and R. LobruttogunaseelandAinda não há avaliações

- 034-Measuring CylinderDocumento4 páginas034-Measuring CylinderAjlan KhanAinda não há avaliações

- EgyE 205 Syllabus Updated 2 - 2011-12Documento2 páginasEgyE 205 Syllabus Updated 2 - 2011-12Michael Calizo PacisAinda não há avaliações

- ADVANCED Inoganic BookDocumento490 páginasADVANCED Inoganic BookHassan Haider100% (1)

- Science Student Laboratory ContractDocumento2 páginasScience Student Laboratory ContractPritos Cabaluan NathanielAinda não há avaliações

- Systematic Qualitative Organic AnalysisDocumento17 páginasSystematic Qualitative Organic Analysisravi@laviAinda não há avaliações

- Precipitation Titration 1Documento25 páginasPrecipitation Titration 1Beyond LbbAinda não há avaliações

- Quality AssuranceDocumento39 páginasQuality AssuranceSherylleen RodriguezAinda não há avaliações

- FirstDocumento19 páginasFirstabhishek733100% (1)

- 6au1 4scientificmethodDocumento12 páginas6au1 4scientificmethodapi-333988042Ainda não há avaliações

- Placebo-Controlled StudiesDocumento2 páginasPlacebo-Controlled StudiesPharm Orok100% (1)

- Standardization of Acid and Base Solutions PDFDocumento3 páginasStandardization of Acid and Base Solutions PDFKassim100% (1)

- APL 2023 LabManualAndReportBookfinal 2Documento107 páginasAPL 2023 LabManualAndReportBookfinal 2Alexandra GutrovaAinda não há avaliações

- Experiment 3Documento8 páginasExperiment 3Fatimah NazliaAinda não há avaliações

- A Classification of Experimental DesignsDocumento15 páginasA Classification of Experimental Designssony21100% (1)

- Guide-Lines to Planning Atomic Spectrometric AnalysisNo EverandGuide-Lines to Planning Atomic Spectrometric AnalysisNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (5)

- Valve TypeDocumento22 páginasValve Typesajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Guage Thickness in MM Weight Per Sq. Ft. Weight Per Pc. Kgs. Pc. IN M/TonDocumento3 páginasGuage Thickness in MM Weight Per Sq. Ft. Weight Per Pc. Kgs. Pc. IN M/Tonsajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Iot-Shm: Internet of Things: Structural Health Monitor: Reinaldo422@Gatech - EduDocumento38 páginasIot-Shm: Internet of Things: Structural Health Monitor: Reinaldo422@Gatech - Edusajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Structural Health MonitoringDocumento14 páginasStructural Health Monitoringsajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Gas Turbine Order Data SampleDocumento13 páginasGas Turbine Order Data Samplesajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Sulzer Sense Wireless Iot Condition Monitoring: Save Time and MoneyDocumento2 páginasSulzer Sense Wireless Iot Condition Monitoring: Save Time and Moneysajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Arizona Public Service Scales Investment in Iiot Based PDM With PetasenseDocumento2 páginasArizona Public Service Scales Investment in Iiot Based PDM With Petasensesajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- PHD RegulationsDocumento25 páginasPHD Regulationssajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- 0105smit PDFDocumento4 páginas0105smit PDFsajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- PDM vs. PLM: It All Starts With PDM: White PaperDocumento7 páginasPDM vs. PLM: It All Starts With PDM: White Papersajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Vibration MachineDocumento7 páginasVibration Machinesajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- The Melsec FX Series: Mitsubishi ElectricDocumento3 páginasThe Melsec FX Series: Mitsubishi Electricsajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Demarest Tide Brochure 2 Pages 2236Documento2 páginasDemarest Tide Brochure 2 Pages 2236sajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Skip Cable LiteratureDocumento2 páginasSkip Cable Literaturesajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- ALE Civils BrochureDocumento25 páginasALE Civils Brochuresajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- Kam Hybrid - ToC Europe - 090610v2Documento31 páginasKam Hybrid - ToC Europe - 090610v2sajjad_naghdi241Ainda não há avaliações

- IMS555 Decision Theory: Week 1Documento16 páginasIMS555 Decision Theory: Week 1pinkpurpleicebabyAinda não há avaliações

- CISCE Results 2023Documento1 páginaCISCE Results 2023aryan guptaAinda não há avaliações

- CHAPTER3Documento6 páginasCHAPTER3PRINCESSGRACE BERMUDEZAinda não há avaliações

- Tutorial Week 3 - Types of LimitsDocumento1 páginaTutorial Week 3 - Types of LimitsXin ErAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis in DermatologyDocumento5 páginasThe Role of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis in Dermatologyanis utamiAinda não há avaliações

- Josefina Castellvi, Biografía Corta MargalefDocumento4 páginasJosefina Castellvi, Biografía Corta MargalefjoshBenAinda não há avaliações

- Science Fiction in The English ClassDocumento125 páginasScience Fiction in The English ClassJoséManuelVeraPalaciosAinda não há avaliações

- 2.6.1b THPM FOR EEE 2018-19Documento4 páginas2.6.1b THPM FOR EEE 2018-19Kumar GirishAinda não há avaliações

- Smart Farming Technology Innovations - Insights and Reflections From The German Smart-AKIS HubDocumento10 páginasSmart Farming Technology Innovations - Insights and Reflections From The German Smart-AKIS HubAbdalrahman ElnakepAinda não há avaliações

- 1 - # Main Topic Head Sub Head AnswerDocumento295 páginas1 - # Main Topic Head Sub Head AnswerMoiz Uddin Qidwai100% (10)

- A Literature Review of Artificial IntelligenceDocumento27 páginasA Literature Review of Artificial IntelligenceUMT Artificial Intelligence Review (UMT-AIR)Ainda não há avaliações

- Bioanalytical Method Validation: Prof. Dr. Muhammad Rashedul IslamDocumento35 páginasBioanalytical Method Validation: Prof. Dr. Muhammad Rashedul IslamKhandaker Nujhat TasnimAinda não há avaliações

- 7 Universal Laws of SuccessDocumento24 páginas7 Universal Laws of SuccessanestesistaAinda não há avaliações

- Physics Chapter 32 Coulombs Law KEYDocumento4 páginasPhysics Chapter 32 Coulombs Law KEYVinz Bryan AlmacenAinda não há avaliações

- Management AssignmentDocumento6 páginasManagement AssignmentabdiAinda não há avaliações

- MMW StatisticsDocumento5 páginasMMW StatisticsCastro, Lorraine Marre C.Ainda não há avaliações

- TCS Interview Process For FresherDocumento3 páginasTCS Interview Process For FresherBALAJIAinda não há avaliações

- BEHAVIORAL Operational ResearchDocumento412 páginasBEHAVIORAL Operational Researchhana100% (2)

- Sri Chaitanya Group (Responses)Documento12 páginasSri Chaitanya Group (Responses)Arzoo ChoudharyAinda não há avaliações

- 10th CertificateDocumento2 páginas10th CertificateUX ༒CONQUERERAinda não há avaliações

- Sea LinkDocumento107 páginasSea LinkFaraz zomaAinda não há avaliações

- Consciousness and Its Evolution: From A Human Being To A Post-Human, Ph.D. ThesisDocumento150 páginasConsciousness and Its Evolution: From A Human Being To A Post-Human, Ph.D. ThesisTaras Handziy100% (1)

- Exam Timetable - Revised June 2023Documento5 páginasExam Timetable - Revised June 2023Ari VaAinda não há avaliações

- Energy and Change (Grade 6 English)Documento64 páginasEnergy and Change (Grade 6 English)Primary Science Programme100% (5)

- Second Quarter Exam Inquiries, Investigation and ImmersionDocumento5 páginasSecond Quarter Exam Inquiries, Investigation and ImmersionLUCIENNE S. SOMORAY100% (1)

- Signed Off - Practical Research 1G11 - q2 - Mod6 - Qualitativeresearch - v3Documento58 páginasSigned Off - Practical Research 1G11 - q2 - Mod6 - Qualitativeresearch - v3Mitzie Bocayong72% (18)

- Module 3Documento15 páginasModule 3Ann BombitaAinda não há avaliações