Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Art

Enviado por

sleepwalkDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Art

Enviado por

sleepwalkDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Art, Design, Craft and Creativity by Joseph Cali I was having a conversation with a number of landscape architects and

garden designers when the subject of someones work came up and someone else called it art. I denied that the work in question was art and gave my reasons. Katsuo Motohashi, a garden designer from Chiba who was in charge of the Japanese Garden Associations International Seminar on the Japanese Garden to be held in Tokyo the following year, was intrigued by my comments. Subsequently he asked me to be one of the speakers at the preliminary event held in Waseda University. This paper is a modified version of the speech, which I gave on that occasion. THEME What is the difference between art, design and craft; why is one of no higher value than the other, and how does creativity play a role in each? SUB-THEME How does this theme apply to the Japanese Garden? Major premise: Art can be either good or bad. Design can be either good or bad. Craft can be either good or bad. Being good or even great is not a criterion for whether something belongs to a certain category such as art or design. The real criteria is intention and, to some degree, method. Good, bad, well made, skillful, expensive, famous are all value judgments unrelated to whether something is art, design, or craft. Basic premise and definitions A standard misinterpretation of art is the formula art = the best. This is a common mistake that leads people to compliment any sort of thing that they feel is in some way exceptional, by labeling it art. Someone will compliment the chief by saying, Thats not food, thats art! or someone else will compliment their favorite hairdresser by saying, He is an artist. Meaning no disrespect to the chief, his work is not art; it is food. And while the hairdresser is no doubt a genius with scissors and brush, he is not an artist. It is more likely that he is an excellent craftsman and designer. In other words, art does not equal the best. Art is not better or more important or of higher quality than design or craft. Art does not imply a value higher than the value of design or craft. Art is a neutral term describing the result of an impulse to create, without any purpose or limitations to that creation other than the artists own desire to carry it out. It is a selfish, self-serving, and largely self-referential activity that requires no special technical knowledge. When it has a value to anyone other than the artist, that value is related to intangible benefits. It may forecast trends in the society in general or in a limited area. It may speak to others on an emotional or psychological level that helps others to understand their own minds and hearts. It may reveal some universal truth or it may speak of one particular truth. It may inspire others to find their voice and attempt to speak through some secondary media or other. It may simply amplify, educate, or entertain. It often has more benefit to the creator than the observer and is often recognized only by the creator and a small circle of observers as having any value at all. It will usually contain some degree of design and craft. Art cannot be created on demand or for a specific price or to fit a specific time frame or function except in the most general of ways. A painter may be asked to create a painting for a certain location for a certain price and within a certain timeframe. Such a work comes close to the definition of design and craft. The degree to which it is art will depend on the strictness of the boundaries under which the work will be accepted as having fulfilled the expectations of the buyer. For example, is it similar to other works by the artist or completely unexpected? Is it in a medium that the artist felt compelled to use, but which has a very short lifespan or no intrinsic value? Is it taking too long or costing too much money and is it therefore curtailed? Does the artist have the right to just give up part way through? To the degree the constraints and commitments confine the work, is the degree to which the work enters the realm of design and craft. (All of this holds true for sculpture, filmmaking, or any other media

used.) In summary, art has no purpose, no direction, no clear criteria for success, and no limitations other than those of the individual or group that creates it. It may or may not include a high level of craft or design. The result of the artistic impulse may be good or bad and the outcome may or may not have value. That value is extremely relative and transient. The degree to which it is considered to have value is not related to whether it is or is not art. Value is related to whether it is considered good art or bad art by the degree of acceptance it receives in its own time or in the future. The value of the materials may be determined and affect the value as an object (i.e. a work in gold or some other precious material that has its own market value) but that is aside from its value as art. By contrast, design has a purpose, it has direction, it has conditions usually set by someone other than the designer, and it has more or less clear criteria for success and the determination of value. Design often requires a specialized knowledge and much of that knowledge is geared toward the production of the design and of its use (for example an architect is a designer who has knowledge of how a building is built and for what purpose it will be used). The production of the design is most often not in the hands of the designer who may or may not direct or participate in the production. Design is by definition the creation of form and content directed toward a specific purpose, such as moving a person from point A to point B. The conditions of that movement (weight of the person, distance, cost, speed, etc.) will strongly determine the outcome of that designa car, bicycle, airplane or ambulance. Cost considerations, available technology, aesthetics, and patents or copyrights held by others will all be factors in determining the direction and outcome of the design. Many if not most of these factors will be outside the control of the designer. The ultimate success and value of the design will be determined by how well it sells, how well it fulfills the purpose intended for the final product (it may be a beautiful knife but does it cut well? it may be an aesthetically pleasing design but is it easy to use? It may be a beautiful advertisement, but does it bring customers into the stores?). How durable it is, how much potential it has for creating new business, etc., as much as how it looks or feels, are essential qualities of design. It is incorrect to say that a design was good but it didnt work or its cost was too high. These are intrinsic conditions of design and if they are not satisfied, the design cannot be said to be good. This notion comes from the mistaken concept that design is mostly about good looks. This is the same misconception that prompts the equation: good design = art. If design is art (at least by the definitions above), it is not good design. But good design is no less than art. It is simply a different animal. In summary, design has a purpose, a direction, rather clear criteria for success, and clear limitations, conditions, restrictions, etc. To the degree that it fulfills or even exceeds all the criteria laid out for it, it is a good or even great design. Its value is usually predetermined as one of the criteria it must meet. That value may also be affected by external conditions unrelated to the design (i.e. a sudden economic downturn or completely new technology), but that will not be a factor in determining if the design was good or not. Nor is its ability to endure over time. Obsolescence may be built into the design and therefore becoming obsolete will be a mark of its success. The amount of participation played by aesthetics will vary from little or none to predominant. It may depend solely on the skill and ability of the designer or it (more likely) will involve the skills and abilities of a small to large number of people. It must have intrinsic value on a scale proportionate to its manufacturing costs and sale price. Finally, craft is similar to design in its purpose, direction and criteria for success. However craft is more equivalent to production, though it is understood that the skill of the craftsman goes a long way in determining the outcome of the product (as opposed to the automated production process which will typically involve craftsman in the creation of the process and its components, rather than in the final product). Craft will employ design but design prerogatives may or may not be within the purview of the craftsman. Generally both design and craft involve some degree of the other. A good craftsman can greatly improve a design with his knowledge of materials and production methods as a designer may produce better craft by introducing new ideas, new aesthetics or new performance criteria. The emphasis of craft is on functionality, durability, consistency of product, and (generally) reproducibility at the same level of quality over a period of time. Good or bad craft will generally relate to the physical (as opposed to the aesthetic or emotive) attributes. Craft operates under basically the same constrictions of time, cost, etc. as design. The aesthetics are largely determined by the design (which may or may not be in the hands of the craftsman) but the level of craft will impact on the aesthetics in a positive or negative manner. The value of craft as good or great is determined when it fulfills or exceeds its requirements, often in service of the

design. In summary, craft has a purpose, a direction, rather clear criteria for success, and clear limitations, conditions, restrictions, etc. To the degree that it fulfills or even exceeds all the criteria laid out for it, it is a good or even great craft. Its value is usually predetermined as one of the criteria it must meet. That value may be affected by external conditions unrelated to the craft (i.e. a sudden changes in material cost or completely new technology), but that will not be a factor in determining if the craft was good or not. Nor is its ability to endure over time. Limited or shortterm use may be one of the parameters. The amount of participation played by aesthetics will vary from little or none to predominant. It may depend solely on the skill and ability of the craftsman or it may involve the skills and abilities of a small to large number of people. The craft must have intrinsic value on a scale proportionate to its manufacturing costs and sale price. Another way to look at similarities and differences is based on the content of the method or process involved in each. ART: Relies heavily on self-determination, individual pursuit of meaning as manifest in the work, experimentation, and mindless activity. Conceptualization and production are usually an organic whole. Art is self-taught or taught by example but there is no clear formula for making good or successful art. DESIGN: Relies heavily upon both self- and group- determination, pursuit of solutions to posited problems, experimentation, some mindless but mostly mindful activity, ability to satisfy numerous conditions toward some useful (usually utilitarian) or applied outcome. Conceptualization and production phases are usually separate (though some trial and error interplay may occur) and production usually relies heavily on coordination with and the skill of others and of technology. Design can be studied and taught with a more or less clear formula for successful if not great design. Depending on the product being designed, a high level of technical knowledge may be needed. CRAFT: Relies heavily on precedent in terms of material and technical capabilities and systems. Attention to physical rather than conceptual aspects is paramount. Indeed, conceptual work may be partially or entirely carried out by others. The work of a single individual or organized group with a rigidly set process is usually involved. One particular group of craftsman are usually limited to a specific group of materials and processes that are well understood and manipulated to a high degree of finish, based on a well-understood set of rules. Craft is studied and learned over a long period of time and must be taught by those with experience in the process, to newcomers in the field. The aim is to assure a consistent and successful outcome over time. Yet another way to view these definitions based on possible criteria of good or bad for each, is by responding to the question, How is Art (Design, Craft) determined to be Good? How is Art Determined to be Good? 1. By the determination of experts in the field 2. By a high commercial value, especially over time 3. By changes in philosophy or in the society, which brings it recognition over time (and therefore deem to have been ahead of its time or prophetic) 4. By the endurance of acclimation over time 5. By popular demand (to view or own it) 6. By the acclaim of peers 7. By the volume of product over time (the durability of the artist) How is Design Determined to be Good? 1. By popular demand (to view or own it) 2. By a high commercial value, especially immediately 3. By the determination of experts in the field 4. By the amount of and distance of dissemination

5. By product strength, durability, and other physical characteristics 6. By the endurance of acclimation over time 7. By the acclaim of users 8. By the speed with which it adapts to changing needs How is Craft Determined to be Good? 1. By popular demand (to view or own it) 2. By a high commercial value, both immediately and over time. 3. By product durability 4. By the endurance of acclimation over time. 5. By product strength, durability, and other physical characteristics 6. By the determination of experts in the field. 7. By the acclaim of users In general, definitions of Art, Design and Craft are relatively new phenomena, stemming largely from the influence of technology and mechanically based production systems including printing, photography, film and computers. One source of confusion about the difference between art, design and craft is in their changing roles in the society over time. In other words, the artist was once the only means of visual reproduction. He was therefore artist, designer, and craftsman rolled into one. Gradually, due to the volume of goods needed and the scale of the product (i.e. castles, bridges, boats, books, etc.), craftsman became increasingly specialized and distanced from art and design (though both of these still employed and emphasized a high degree of craftsmanship on the part of individual artist/designers). Painting, drawing, and sculpture for example, once played a very important role in representation and were essential to the dissemination of knowledge. As these roles were taken over by printing, photography, film, TV, Xray, etc., more traditional arts and crafts veered toward self-expression, abstraction, self-reference and experimentation, although they still play some role in representation. Technology largely relegated art to the position of non-essential item. Does this mean that art is more or less art than it once was? No. It means that the advent of technology removed most of the functional aspectsor to put it another way, the design and craft aspectsfrom art and freed it (or pushed it) to be more experimental, theoretical, mystical and heretical (and also allowed it to be sloppier, less durable, and more transient). Take, for example, Leonardo. Was he an artist? Unquestionably. Does that mean that everything he did was art? Certainly not! He was also a designer, an architect, an engineer, a scientist, a genius, and an individual of great creative power and highly developed skills. This last point is key to why the work of the ancients is more often considered artno matter who made it or what it isas compared to contemporary art. It is simply because the ancients exhibited a high level of craft and, in our age of machine-made objects, a high degree of hand-skill is highly valued and easily mistaken for art. But for the people of the age in which this work was created, it was not a question of art, but one of function, beauty, and virtue. The work had a recognized purpose, without which it would be nothing but folly. However, once printing and then photo reproduction came on the scene the great divide between the necessities of quick and inexpensive and the nice to haves of hand-made but slow and costly, began in earnest. In other words, the difference between those products with an easily fixed (though fluctuating) value vs. those products that are difficult to value came to be defined by what was readily available and what was not. Technology put things conveniently within reach of everyone. Though each unit thus became cheap, the total value to the society became great. Whereas those things which were or are not yet subject to technology are expensive by unit cost, but far less valuable to the society as a whole. (For example, a printed paperback is reproduced by the hundreds of thousands and though each book is cheap the value to the society is much greater than a handmade, illuminated book which is a valuable object that offers little value to the society in general.) Another source of confusion is the review of historical works through the filter of modern sensibilities. This often causes the label art to be attached to objects simply because they have survived from ancient civilizations. Museums are full of such objects, most of which demonstrate varying degrees and combinations of art, design, and craft. Many are of little value other than that they are old.

The Role of Creativity Creativity is the ability to reach within and externalize the internal. It involves combining emotions, memories, knowledge, experience and other human capacities, in the service of a physical entity. That entity may be an object, a movement (a dance), sounds (music), or any type of physical manifestation. Creativity is the opposite of reproduction in that it is original production. Though the result of the creative act will likely retain some aspects of the physical world that is already manifest and in which its creator exists, it is likely to result in something new. Creativity is usually essential to both good art and good design and usually implies a degree of uniqueness, originality and invention. Creativity is however less important to craft (except in creating new methods of production) than is the perfection of method. Such perfection usually happens through the repetition of a certain set of skills and materials. Relationship of this theme to the Japanese Garden Returning to the original focus of this piece, which began as a talk to the Japanese Garden Society, the relationship is in the question Is the Japanese Garden Art? Seen in the light of my basic premises on art, design, and craft, as outlined above, the simple answer is generally, no. To state it more completely, where the garden has been made to a predetermined area, at a predetermined cost and time schedule, with demands for durability etc. and with other demands and needs of the customer in mindas is the case with almost every gardenit is not art. In that case it is design. On the other hand, if it has been made with no purpose, no restriction of area, budget, client desire, etc., and solely for the purpose of exploring the possibility of expression through the use of materials which may or may not normally be associated with Japanese gardens, is can be art. Again, this does not answer the question of whether a particular garden is good or bad, but only if it is art. It also does not imply thatas designit is of lesser value, lesser skill or lesser importance than art. Considering this definition, it is clear that the vast majority of Japanese gardens are not art but design. Furthermore, the realization of the design, as with creations such as music and architecture, is highly dependent on craft. In other words, while both good art and good design almost always rely on creativity, the manifestation of good design relies more heavily on good craft than does good artwhich may be totally or almost totally devoid of craft. The visual techniques employed in the design of Japanese gardens have a great deal in common with other forms of two and three-dimensional representational techniques. The similarities between the painters use of composition, foreshortening, light and shade, etc., and the design of gardens intended for viewing from a position inside an adjacent room, are particularly striking. The Japanese garden is generally a combination of design principles and craftsmanship, using primarily living and non-living natural materials, applied to a specific site with a specific effect in mind. That effect may be to invoke a popular scene from some part of the country or a literary passage in a famous story. It may be intended to recall a natural forest or lakeside setting. But whatever the design or effect, the Japanese Garden generally lies squarely in the area between design and craft. As design, it seeks to find a solution to a posited problem. This problem is usually something like how can a certain piece of land be developed, under certain circumstances and with certain conditions, to create what is considered by the owner of the property, the creator, other observers, and historical presidents to be a meaningful and or pleasing environment. As craft, it relies heavily on a certain set of materials, manipulated according to certain rules and historical precedents, environmental conditions, etc., by people trained in a particular set of skills, under the supervision of the designer or his proxy. The execution of the design relies heavily on the hand of the craftsman who may or may not be the designer. The results must be reasonably durable, functional and conform to some standard of beauty and quality. The success of the design is virtually indistinguishable from the quality of the craft. Can the Japanese Garden ever be considered art? This is a difficult and open question. Historically, I believe that the early karesansui (sand and stone) gardens come

closest to the definition of art proposed in this paper. I am not referring here to the original dry landscape as described in the twelfth century garden treatise known as Sakuteiki but to those gardens associated with Zen. Certainly, it appears that the lack of pleasing effect displayed by such gardens, as well as the lack of basic garden materials such as plants and water, displays a disregard for the typical conventions of garden design. It would appear that Buddhist monks created most of these early gardens in areas adjacent to quarters not open to the public. Such gardens display a leap of thinking more indicative of art than design or craft. In seems that such gardens were created as an aid to meditation. They seem to have been inspired by Chinese-style ink painting of mountainous and cloud-filled landscapes, many of which display an ethereal, almost abstract image, also indicative of karesansui gardens. These suibokuga ink-wash paintings and techniques were transmitted primarily by Chan monks from China through the Zen temples and created in Japan to similar effect. The connection between the characteristics of suibokuga and karesansui seems obvious even to the casual observer but it may be that one was not a direct influence of the other. Rather it was likely the result of the pervading atmosphere surrounding both, of a search for spiritual enlightenment and the austerity that accompanied that search. To the degree that such gardens lacked any conditions or limitations on their making (other than a wall-enclosed area of some fixed size) and to the degree that their only utilitarian aspect was to elicit an emotional or spiritual responseI believe they can be considered art. (However whether they can be considered gardens or sculptural installations is a problem for another paper.) Although much has been made of the craft of gardens such as Ryoan-jisuch as in the placement of its limited number of stonesI suspect that this was always secondary to the intentions of the creators. In other words, unlike most Japanese gardens, these karesansui rely far less on craft than on a freeform play between the creator and a limited number of materials, with an eye toward an abstract expression. Their affinity to art is therefore far greater than other garden forms. Again, this is not a value judgment as to rather they are good or bad. A more contemporary example, which I do not consider to be art, is the work of Mirei Shigemori (1896-1975). Though I do not consider his work art, I mention this work for several reasons. Firstly, it is often mistaken for art because of its occasionally radical departure from more traditional Japanese garden design. Shigemori was a writer, researcher and designer who had a profound understanding of traditional garden design. He single handily tried to drag traditional garden design into the modern world. To do this, he employed radically stylized, curvilinear designs, with copious use of cement and stucco. There is no doubt that his work is as much design and craft as any traditional garden. Though he used his garden design to make a design statement unlike anything that had been seen before, and his use of some untypical garden materials is provocative, it was still very much set within the garden milieu. Secondly, his work shows the difficulty in actually taking the garden out of its position in design and craft (where it has a traditionally defined and accepted role as pleasing environment), and turning it into an expression of an individual vision. Because of his radical view of the garden he is equally praised and reviled. I have been told my any number of garden designer/builders that Shigemoris work has nothing to do with Japanese gardens and they consider his work quite ugly. Certainly, not all of his designs have been successful and many of his gardens have been neglected and are in poor repair. Those gardens seem to point out the failure of a material such as colored concrete to either regenerate itself or develop a pleasing patina as it ages. But I suspect the real problem that many garden designers have with the work is the uncomfortable challenge it poses to those working in a traditional craft. The challenge is how to stay relevant in the contemporary world and whether one need try or not.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Chemical and Biological Weapons Chair ReportDocumento9 páginasChemical and Biological Weapons Chair ReportHong Kong MUN 2013100% (1)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Technical Analysis CourseDocumento51 páginasTechnical Analysis CourseAkshay Chordiya100% (1)

- 4 Economics Books You Must Read To Understand How The World Works - by Michelle Middleton - Ascent PublicationDocumento10 páginas4 Economics Books You Must Read To Understand How The World Works - by Michelle Middleton - Ascent Publicationjayeshshah75Ainda não há avaliações

- Chenrezi Sadhana A4Documento42 páginasChenrezi Sadhana A4kamma100% (7)

- 06 - Wreak Bodily HavokDocumento40 páginas06 - Wreak Bodily HavokJivoAinda não há avaliações

- Santrock Section 1 Chapter 1Documento19 páginasSantrock Section 1 Chapter 1Assumpta Minette Burgos75% (8)

- Prayer Points 7 Day Prayer Fasting PerfectionDocumento4 páginasPrayer Points 7 Day Prayer Fasting PerfectionBenjamin Adelwini Bugri100% (6)

- Ancient Buddhism de Visser Volume 2Documento347 páginasAncient Buddhism de Visser Volume 2sleepwalkAinda não há avaliações

- 2003catalog PDFDocumento25 páginas2003catalog PDFPH "Pete" PetersAinda não há avaliações

- spp127 GetesDocumento137 páginasspp127 GetessleepwalkAinda não há avaliações

- A Dutch New Year at The Shirando AcademyDocumento47 páginasA Dutch New Year at The Shirando AcademysleepwalkAinda não há avaliações

- Munakata FamilyDocumento140 páginasMunakata FamilysleepwalkAinda não há avaliações

- 1040 A Day in The Life of A Veterinary Technician PDFDocumento7 páginas1040 A Day in The Life of A Veterinary Technician PDFSedat KorkmazAinda não há avaliações

- HG G2 Q1 W57 Module 3 RTPDocumento11 páginasHG G2 Q1 W57 Module 3 RTPJennilyn Amable Democrito100% (1)

- Nava V Artuz AC No. 7253Documento7 páginasNava V Artuz AC No. 7253MACASERO JACQUILOUAinda não há avaliações

- Micro Fibra Sintetica at 06-MapeiDocumento2 páginasMicro Fibra Sintetica at 06-MapeiSergio GonzalezAinda não há avaliações

- RPL201201H251301 EN Brochure 3Documento11 páginasRPL201201H251301 EN Brochure 3vitor rodriguesAinda não há avaliações

- Individual Development Plans: A. Teaching Competencies (PPST) Objective 13, KRA 4 Objective 1, KRA 1Documento2 páginasIndividual Development Plans: A. Teaching Competencies (PPST) Objective 13, KRA 4 Objective 1, KRA 1Angelo VillafrancaAinda não há avaliações

- Forum Discussion #7 UtilitarianismDocumento3 páginasForum Discussion #7 UtilitarianismLisel SalibioAinda não há avaliações

- DIN EN 16842-1: in Case of Doubt, The German-Language Original Shall Be Considered AuthoritativeDocumento23 páginasDIN EN 16842-1: in Case of Doubt, The German-Language Original Shall Be Considered AuthoritativeanupthattaAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To Human Resources ManagementDocumento14 páginasIntroduction To Human Resources ManagementEvan NoorAinda não há avaliações

- @PAKET A - TPM BAHASA INGGRIS KuDocumento37 páginas@PAKET A - TPM BAHASA INGGRIS KuRamona DessiatriAinda não há avaliações

- Schedule 1 Allison Manufacturing Sales Budget For The Quarter I Ended March 31 First QuarterDocumento16 páginasSchedule 1 Allison Manufacturing Sales Budget For The Quarter I Ended March 31 First QuarterSultanz Farkhan SukmanaAinda não há avaliações

- Micro Analysis Report - Int1Documento3 páginasMicro Analysis Report - Int1kousikkumaarAinda não há avaliações

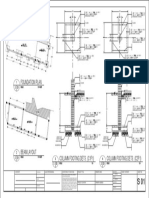

- Foundation Plan: Scale 1:100 MTSDocumento1 páginaFoundation Plan: Scale 1:100 MTSJayson Ayon MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- Oral Communication in Context - Week 8Documento22 páginasOral Communication in Context - Week 8Sheldon Jet PaglinawanAinda não há avaliações

- 04 TP FinancialDocumento4 páginas04 TP Financialbless erika lendroAinda não há avaliações

- Handbook For Inspection of Ships and Issuance of Ship Sanitation CertificatesDocumento150 páginasHandbook For Inspection of Ships and Issuance of Ship Sanitation CertificatesManoj KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Holidays Homework 12Documento26 páginasHolidays Homework 12richa agarwalAinda não há avaliações

- Vishnu Dental College: Secured Loans Gross BlockDocumento1 páginaVishnu Dental College: Secured Loans Gross BlockSai Malavika TuluguAinda não há avaliações

- Proximity Principle of DesignDocumento6 páginasProximity Principle of DesignSukhdeepAinda não há avaliações

- Napoleon Lacroze Von Sanden - Crony Capitalism in ArgentinaDocumento1 páginaNapoleon Lacroze Von Sanden - Crony Capitalism in ArgentinaBoney LacrozeAinda não há avaliações

- Essay On Stamp CollectionDocumento5 páginasEssay On Stamp Collectionezmt6r5c100% (2)

- 띵동 엄마 영어 소책자 (Day1~30)Documento33 páginas띵동 엄마 영어 소책자 (Day1~30)Thu Hằng PhạmAinda não há avaliações