Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Berman & Bradt, 2006

Enviado por

Anamaria StanDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Berman & Bradt, 2006

Enviado por

Anamaria StanDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 2006, Vol. 37, No.

3, 244 253

Copyright 2006 by the American Psychological Association 0735-7028/06/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0735-7028.37.3.244

Executive Coaching and Consulting: Different Strokes for Different Folks

William H. Berman

APT, Inc.

George Bradt

PrimeGenesis, LLC

Increasing frustration with the politics and economics of traditional mental health care has led many psychologists to consider shifting to or adding executive coaching as a core competency in their practices. Experience with work-related issues in clinical practice makes this appear to be a logical extension of traditional clinical and counseling work. There are many types of executive coaching and consulting, however, and only some of these relate to traditional mental health services. The authors propose a 4-category model of executive coaching defined by the intersection of focus (business vs. personal) and technique (brief-directive vs. extended-Socratic). Developmental coaching, which addresses longstanding behavior problems in both personal and work settings, is most likely to fit with traditional psychological training. Training or experience in the upper levels of the business world is essential to developing the capability to help corporate leaders with a broad range of needs and situations in which they find themselves. Keywords: executive, coaching, consulting, business, interpersonal skills

Consulting, industrial/organizational (I/O), and clinical psychology have increasingly embraced the concept of executive coaching over the past 10 years. At the extreme end of the spectrum, some have argued that only psychologists should set standards for executive coaching (Brotman, Liberi, & Wasylyshyn, 1998), or that psychoanalytic training is uniquely beneficial in the coaching endeavor (Kilburg, 2000). Others have argued more reasonably that psychologists are particularly familiar with theories and methods regarding individual behavior change, and are skilled in managing relationships in which self-reflection and self-improvement are central (Kampa-Kokesch & Anderson, 2001). Their view, however, reflects a somewhat self-limiting perspective on executive coaching, as many of the issues executives face are not related to personal insight, stress management or individual behavior change. We believe that knowledge, understanding and experience in the business world are essential to the delivery of effective coaching and consulting in most coaching assignments. The rules,

WILLIAM H. BERMAN is a licensed psychologist who received his doctorate from Yale University. He has worked with corporations, health care organizations, and executives for more than 20 years, including BristolMyers Squibb, Diageo, Starwood Hotels, and Xerox. He is currently a Director with APT, Inc. and a partner with PrimeGenesis, LLC. Previously he was a director, professional services at The Echo Group, and associate professor of psychology at Fordham University. His current research includes executive coaching and leadership development. GEORGE BRADT is the founder and managing director of PrimeGenesis, LLC, a consulting firm in Stamford, CT. He received his MBA from the Wharton School of Business. He has worked for more than 20 years as a senior manager and executive with J.D. Power & Associates, Coca-Cola, Lever Brothers, and Proctor & Gamble. His current research focuses on executive on-boarding and leadership acceleration. CORRESPONDENCE CONCERNING THIS ARTICLE should be addressed to William H. Berman, 123 MacGregor Drive, Stamford, CT 06902. E-mail: bill@doctorberman.net 244

mores, cultures, values and systems in corporate settings are virtually impossible to master without experience in these settings, and the majority of psychologists are very limited in their understanding of this culture. In order to follow our conceptualization of executive coaching and consulting, it may help to understand the diversity of our backgrounds and experiences. The first author began his career as a clinician. He was trained in psychodynamic and systems theory, worked with individuals and families, and treated persons with schizophrenia, other major mental illnesses, and families in crisis. He taught in an American Psychological Association (APA)approved clinical psychology graduate program, and published clinically oriented research. After about 15 years, a medical colleague asked him to help with a company to which the physician was consulting. The problem was described as one of stress management for the editorial department of a fast-growing educational consulting group. The first author met with the chief executive officer (CEO), who said he was concerned about the level of stress and frustration in this team. The CEO was a true entrepreneur, a highly driven visionary and a man who was very devoted to his company and his staff. He was generally kind, very generous, and fiercely loyal to all of them. After meeting with the head of the editorial department, and providing some stress management workshops and tools, it became clear that a key part of the difficulty for the department reflected a company-wide issue. The first author observed that the CEO had a tendency to interrupt people in meetings and lose his temper when people didnt act the way he expected. Other people at the company adopted this pattern of behavior, and many of them verbally abused other people on their teams, without the kindness, generosity, and loyalty that the CEO demonstrated. In this organization, as in family systems, the symptoms in one area (stress in one department) were the expression of dysfunctions in other parts of the system. The first author convinced the CEO that he was a

SPECIAL SECTION: EXECUTIVE COACHING AND CONSULTING

245

part of the problem, because people were only emulating his weaknesses, not his strengths. He worked to develop better frustration tolerance and self-control, and to communicate his expectations for the same self-control for his leadership group. Two years later, the first author left academics and moved full-time into the business world. He spent five years running his own small business and four years working in a leadership position in a software company. Now he works with a variety of public and private companies and their executives to develop soft-side skills such as alignment, collaboration, and problem-solving, with the focus of improving business performance measured by revenues, profits, and market share. The second author gained a unique perspective on helping executives accelerate transitions though years of experience as a line manager in large corporations. After spending several years in the business world, he attended the Wharton School of Business, where he received an MBA. Afterward, he progressed through a series of sales, marketing, and general management roles around the world at Fortune 500 companies including Unilever, Procter & Gamble, and Coca-Cola. He then worked as chief executive of J.D. Power & Associates Power Information Network spin-off. In these positions he developed a methodology for improving the transition of people in his management teams. His methodology emphasized creating efficient processes, rapidly aligning team members, and clarifying goals and objectives. He left corporate work to build a team of former executives and organizational consultants whose work focuses on improving senior executives transitions through training in this methodology. As advisors to business leaders, their goal is business success. In summary, the authors come from highly divergent backgrounds, with very different training and experience. In the course of our collaboration, we have begun to differentiate our skills and competencies, and identify both systemic and individual methods to best help our clients. This article describes one of the ways in which we have defined and clarified the balance between business and psychological competencies in executive coaching.

year since 1996 (Berglas, 2002). Corporations are paying increasingly steep fees for external coaches, so much so that the coaching and executive consulting segment is estimated to be a more than $1 billion industry at present (Sherman & Freas, 2004). This does not include the internal supervisorsubordinate relationship, which is increasingly referred to as coaching, or the plethora of other personal coaches, including job coaches, life coaches, and family coaches (Stern, 2004). In spite of this rapid growth and burgeoning interest, executive coaching remains somewhat vaguely defined. Coaching differs from organizational or management consulting in that it focuses on the individual leader and his or her team, emphasizes an actionoriented rather than an experiential approach, and focuses on what are often called soft-side skills. What coaching encompasses, how it is practiced, and who is qualified to provide it all remain subjects of discussion and debate. Chief learning officers and chief human resource (HR) officers, who are the most common purchasers of coaching services, need to understand how to match their employees needs with what is offered. We argue that executive coaching is not a one-dimensional enterprise. The development of a coherent, comprehensible theory of intervention requires a clearer delineation of the types of problems and situations that coaching deals with. We are proposing a four-category model of executive coaching that defines the approach in terms of the goals of the coaching assignment (Diedrich, 1996), the scope of work, and the type of business scenarios involved (see Figure 1): Facilitative coaching. Facilitative coaching ensures that new leaders or leaders taking on new challenges implement the steps most likely to achieve their personal and corporate strategic goals. It can also help leaders who are already successful move their team to high-performing status (Bradt, Check & Pedraza, 2006). This type of coaching is short-term, business-focused and directive. It emphasizes the application of strategic planning, business modeling, and team-building skills. It may also include the facilitation of sophisticated leadership skills, but in general focuses on core leadership competencies. Executive consulting. Executive consulting offers senior leaders a thoughtful, challenging relationship with a neutral third party to help think through difficult issues and decisions. This type of coaching uses a more Socratic (e.g., nondirective, questioning) approach emphasizing creative problem solving, decision-making, and capitalizing on strengths. It can be brief in duration or more extended, depending on the needs and interests of the executive. Restorative coaching. Restorative coaching helps a valued individual overcome short-term or temporary difficulties in the workplace due to personal or organizational changes. This type of coaching emphasizes the identification of personal, situational, and organizational obstacles to the use of existing skills (production deficits) as well as the development and implementation of new skills that were not required in previous positions. It tends to be short-term and focused, using a combination of individual and team-focused interventions designed to remove personal and organizational obstacles to execution of business strategies.

The Growth of Coaching and Executive Consulting

The demand for executive coaching is growing by leaps and bounds. Recent research indicates that between 35% to 40% of new managers fail within the first 18 months (Fisher, 1998, 2005). The costs of employee turnover at the higher levels of an organization are exorbitant. Replacing a manager can cost upward of $150,000, and replacing an executive (vice president or above) who doesnt work out can cost a company as much as $750,000 in one year (McCune, 1999). As a result, organizations are looking to consultants to deal with problem employees, facilitate transitions, and help manage personalities and interpersonal conflicts in leadership teams. In addition, leaders look to these advisors to help improve their performance, particularly when those executives are taking on new challenges and mandates. While some very large companies (e.g., Starwood Hotels, Bristol-Myers Squibb) have created internal coaching and leadership development teams, many organizations rely on external coaches for senior-level consultations because of confidentiality and privacy issues. Growth of the supply of executive coaches may be outstripping demand. The number of coaches has grown by more than 35% per

246

BERMAN AND BRADT

Figure 1.

Four-category model of executive coaching.

Developmental coaching. Developmental coaching builds strengths and alleviates deficits in a mission-critical individual who has substantial and long-standing challenges and interpersonal issues (Peterson, 1996). These are people who either have long-standing interpersonal problems or are lacking in the core skills needed to lead high-performing teams. The intervention tends to be relatively long-term (more than six months), and emphasizes personal rather than technical or business issues. Each approach brings with it recommended methods and interventions, qualifications and styles of providers, and specific objectives within the diverse needs of executives and leadership teams. Each approach is elaborated in detail below. There is very little empirical research to guide or clarify these approaches. Recent articles by Kampa-Kokesch and Anderson (2001) and Sherman and Freas (2004) have summarized the research, and we do not try to duplicate their work. In short, Kampa-Kokesch and Anderson (2001) reviewed seven empirical studies, none of which meet APA Division 12 standards for empirically supported treatments. Only three studies addressed outcomes at all (Gegner, 1997; Hall, Otazo, & Hollenbeck, 1999; Laske, 1999), and two of the three are unpublished masters or doctoral theses. The third (Hall et al., 1999) provided primarily qualitative data and blended interview material with practical experience of the authors. There are several reasons for the lack of research, including the relative novelty of the field (for psychology), the confidentiality needs of the participants, and the lack of any consistently accepted theory to guide the research. As a result, the vast majority of published work in this field is based on brief case studies (Kilburg, 2004), or books published by individuals with experience, reputation, or both (e.g., Berglas, 2002; Buckingham & Clifton, 2001; Kilburg, 2000; Lencione, 2001). We have not conducted research to validate a model for coaching competencies; rather, we are proposing a model that may be of heuristic value to individuals providing, purchasing, or seeking executive consultation services, and those considering conducting research on executive coaching and consulting.

The Four Methods Facilitative Coaching

Facilitative coaching is perhaps the approach least familiar to clinical, consulting and organizational psychology, in large part because the requisite skills are not commonly found in psychologists training and experience. Facilitative coaching can be seen as the primary prevention methodology of the coaching world, providing skills training and facilitation for individuals who are not yet at risk for organizational pathology. Corporate America requires that its rising stars have substantial depth of knowledge in areas like marketing, sales, finance, and operations. College and MBA graduates spend scores of hours each week writing papers, analyzing financials, and reviewing business models and practices. Their goal is to be promoted to management and leadership positions, where they will be able to direct those who research, write, analyze, and modify. Very few of them, however, are trained in the basics of managing and leading, relying on their intuition and experience with superiors who may or may not have been competent or successful. As a result, as many as 40% of new leaders fail within the first two years (McCune, 1999). This is where the facilitative coach adds benefit. In the ideal world, the facilitative coach begins before day one with a leader, providing practical models and recommendations for creating a good initial impression. These on-boarding experts work with the new executive to build a strong reputation and strategic focus in the first days and weeks in their position. The coachs job is to ensure that new leaders take the steps that experience and leadership theory strongly suggest will lead to better business outcomes. A sample of appropriate leadership actions and the translation of sample jargon terms common in the business world are provided in Table 1. The jargon we use may be unfamiliar for many readers. These terms are common business-speak, found in almost any leadership competency model (Office of Personnel Management, 1998), strategic plan, or current business journal. All executive coaches, and especially the facilitative coaches, have to be familiar with the language of business in order to have credibility. Facilitative coaches should have hands-on experience in the business world, and ideally should have had substantial exposure to business,

SPECIAL SECTION: EXECUTIVE COACHING AND CONSULTING

247

Table 1 Sample Leadership Actions and Translations Into Non-Jargon English

Leadership actions Building alliances with colleagues, matrix partners, and both internal and external customers Non-jargon translations Create ongoing, constructive relationships with colleagues, individuals whom you rely on but who do not report to you, and both regular customers and individuals in the organization to whom you provide services. Make sure that everyone on the team is working on the same goals with the same priorities, and that the teams goals and priorities are the same as the organizations. Work with individuals to make sure they share your goals and objectives and are motivated to achieve those goals and objectives. Consider long-term directions for the team and the organization and build action plans, including resources, delivery dates, and identifying responsible parties, that will lead to achieving those goals. Help to hire, train, encourage, and hold onto talented individuals who work for the company.

Creating alignment within ones team, and between the team and the organization Motivating and influencing to achieve corporate goals Thinking and planning strategically

Facilitating the selection, development and retention of human capital

leadership and organizational theory and practice (Hays & Brown, 2004). Many psychologists will not be successful in this type of practice, because most of us have not spent time in corporate settings. An alternative for psychologists is to partner with someone with substantial line management experience. The practice of facilitative coaching is highly directive, focused, and intensive. Executive on-boarding has the greatest chance of success if it begins before the first day the executive starts working. This is because everything executives do and dont do, say and dont say, communicates to the team even before they officially start. A key job of the facilitative coach is to help the executive plan out those prestart and initial conversations. In most facilitative coaching, detailed assessments using either 360 assessments1 or personality and cognitive assessments are of relatively little value. The assumption in these cases is that the individual has been evaluated during the selection process, and is too new to the organization for a 360 to be useful. The only assessment that might be useful is an evaluation of the organizational climate. Since on-boarding assignments do not assume any problems or obstacles beyond starting from scratch, HR representatives may be able to provide cultural information sufficient for a good beginning. The primary objective of the beginning leader is to ensure that he or she has the resources and talent needed to accomplish goals, has them in the right positions, and has them aligned with each other and focused on achieving their goals (Bradt et al., 2006). The five components of this process, referred to as the Building Blocks of Tactical Capacity, include: 1. Defining the imperative: Create a shared focus and strategic plan for the team; Developing the milestones: Implement a team-based process for meeting targets and ensuring the accountability of team members; Creating early wins: Identify one or two goals that can be

achieved within the first three to six months, which will demonstrate the leaders and the teams competence and ability to achieve explicit goals, which remains with them through difficult times; 4. Define and allocate roles: Ensure all team members are in the right positions with the best fitting roles; and Evolving the culture: Move the organizational culture in the direction of alignment, collaboration, accountability, and enterprise excellence.

5.

Case example. One of our clients was taking over a large organization that was in trouble. While the organization had been achieving its annual goals by adding new peripheral products, the health of its core business had been declining steadily over time. This new leader, Janice, needed to change the mind-set of her team to refocus the business on its core competencies and reinvigorate growth. We were hired by Janices company to make sure that she took all the right steps. They had had a bad experience with her predecessor, and so retained us to increase the probability of her success. We met with Janice and advised her to implement the Building Blocks of Tactical Capacity. We played a consultative role in defining the imperative for her team (Step 1). Janice drafted her initial ideas and then took them to her direct reports (individuals who are subordinate and report directly to her) and key peers (individuals who report to the same person she does) one at a time for their input. After assembling the

1 A 360 assessment is a method of assessing an individual on business, technical, and personal competencies that are essential to his or her job function. Typically, it includes ratings of the individual on identified capabilities from supervisors, peers, subordinates, and other individuals who work with the client. This provides a balanced view of the individual that is not overly weighted by either allies or opponents (Velsor, Leslie & Fleenor, 1997).

2.

3.

248

BERMAN AND BRADT

ideas and feedback, Janice shared her goals, strategies, and tactics with her team. Our role was to help her map out the process she needed to follow, help draft the imperative, and provide feedback along the way regarding the content and style of her message to her team. Step 2 guided Janice to hold frequent team-focused meetings in which team members focused on obstacles to milestones most relevant to the entire group. Her bias was to hold individual meetings with her direct reports rather than team meetings. She was advised to move information sharing to written documents disseminated prior to a team meeting, and was trained to use weekly meetings as fully networked discussions on critical issues and priority setting. Her more usual dialogues between leader and subordinate became less frequent and shorter. The coach helped outline the process, deployed standard tracking forms used to monitor progress and actively facilitated the early milestone meetings until the process was embedded in the teams behavioral repertoire. Using Step 3, Janice designated champions (individuals responsible for execution of the strategy) for each of three early milestones to be used in the Early Wins step. These champions formed subteams that were supported by both Janice and the coach to ensure they hit the ground running. The coach provided additional consultation and support to these team members. Empowering and facilitating the champions allowed the team to move these areas forward faster, which contributed to early business acceleration. Step 4 ensures that the right people are in the right positions. It is well-known that this is critical to any business success (Collins, 2001). Janice made several moves to shift people into different positions, and contemplated whether she had the right people in the organization. This is a difficult move for many managers, who worry about the hidden costs to terminating long-term incumbents including resentment by allies of the incumbent and loss of organizational knowledge. Janice quickly identified two of her direct reports who did not fit with her new organization. Under guidance from her coach, she learned how to move these people out, and began recruiting replacements quickly. She also worked with her direct reports to identify individuals below them who were not performing or not aligned with the new imperative. The coach helped Janice think through these moves, and encouraged her to take action swiftly rather than delaying the inevitable or tolerating mediocrity. The final step of evolving the culture (Step 5) required direct assistance from the coach. The coach mapped coalitions of contributors, detractors, and observers, and designed a communication campaign to drive the entire organization toward the new culture. The initial steps of this cultural evolution began with the coachs first meeting with Janice before she started her position, so that her campaign could begin on her first day. The campaign, similar to a marketing campaign, was based on a single key message and core communication points that were revisited repeatedly in different media, with different people over time. It continued far into the first six months of Janices work, and defined her approach to her first year. The result was a leader who could deliver better results faster, because the coach provided business strategies, marketing, and communication skills, and supported decisive action. Janice turned the core business around within three months to the point where

her organization moved from being a financial drain to a results leader. The coach provided leverage, experience, and support to enable her to accomplish her goals faster.

Executive Consulting

Executive consulting is the term we have adopted for the approach to coaching that is designed to help a senior leader improve on an already successful career. The executive consultant serves as a sounding board who can help leaders anticipate, plan, and think through strategic, political, organizational and personal issues (Peterson, 1996) with only one goal: to make the executive as successful as possible. As corporations become increasingly focused on the short term, and executives see intercompany movement as essential to their own growth, it becomes harder to identify unbiased mentors and allies within the organization. A thoughtful, challenging, and neutral third party can help executives consider, analyze, and resolve issues that arise within their own teams, within the leadership team to which they belong in the larger corporation, and within the industry as a whole. Executive consulting typically begins when the executive has a problem to solve or is feeling stressed, but can become a longer term intermittent or ongoing involvement. What skills and competencies does an executive consultant need? First, he or she must be able to listen carefully, ask insightful questions, and raise alternatives. He or she should use a Socratic style of questioning more often than directive guidance. The consultant must have enough business experience and knowledge to be able to understand the issues that need to be considered. An understanding of both general systems theory and organizational systems is critical. The first authors experience with family systems theory and constructivist theory was tremendously helpful, as it facilitated understanding of Senges concept of the learning organization (Senge, 1990; Senge, Kleiner, Roberts, Ross, & Smith, 1994) and Argyriss research on organizations (e.g., Argyris, 1990), some of the seminal works in organizational theory. The executive consultant must be able to translate theory into practice, giving specific direction to the executive based on a thorough knowledge of personality, social behavior, group theory, and systems theory as well as what is known about the organization and the individual (Kilburg, 2000). Mono-theoretical psychologists will have difficulty with this type of coaching, because intrapsychic, interpersonal, behavioral, and systems components are simultaneously at play with the larger political, economic, and organizational factors. All good clinicians rely on both their theoretical knowledge and their world knowledge drawn from experience and activity. The consultant should take a strength-based approach (Buckingham & Clifton, 2001), helping the executive build on what he or she already does well. Last but not least, the executive consultant must be a creative problem-solver, able to bring disparate ideas, knowledge, and insight to bear on problems, including personnel issues, alliance building, and efforts to increase power and authority. The role of the consultant with this type of coaching is active and directive, although direction must come via synthesis and integration of what the executive describes. It is the responsibility of the executive to bring issues, ideas and concerns to the consultant. It is the job of the executive consultant to ensure that the executive can understand and articulate the issues, addressing

SPECIAL SECTION: EXECUTIVE COACHING AND CONSULTING

249

potential challenges and strategies with enough time to weigh options, consider alternatives, and consult with others if needed. The consultant guides the executive to evaluate the problem from personal, systemic, and strategic viewpoints. He or she should facilitate decision making, watching for decision pitfalls such as single-issue choices and short-term decision criteria (Peterson & Sokol, 2005). Establishing objective measurements for success, and determining procedures for testing, implementing, and evaluating choices are also important aspects of the consulting function. Psychologists can be quite useful in this role if they have the requisite background and experience, although they are not the only people who are qualified and capable of providing this kind of consulting. As with any therapeutic experience, careful listening, attention to what is not said as well as what is said, and rephrasing and reflecting are essential. Experiences with cognitive behavioral interventions that emphasize decisionmaking and problem-solving techniques (Richard, 2003) are among the most useful of skills. In addition, an understanding of how groups, teams, and organizations work is also important if the consultant is to help the executive deal with a complex and politically sensitive team. A broad knowledge of personality, cognitive, and constructivist theory is extremely useful. Many executives (and most other people) make assumptions about how others think and feel based on how they experience situations. Explaining the motives, perceptions, and feelings of others when they are substantially different from the executives experience can help them find new ways of addressing old problems. It can be valuable for the executive consultant to meet with or consult to the leaders team as a whole, particularly if there are obstacles or challenges that are team related. For example, leaders can inadvertently encourage hub-and-spoke communications styles in which each member of a team speaks primarily with the leader, who then holds or passes information to other team members. This is a common team configuration that maintains the centrality of the leader, but slows communication and interferes with synergistic functioning in a team. Having an understanding of group process and systems theory makes it easier to help an executive understand the alternatives to his or her current strategy. Case example. Dave began talking about work issues with his consultant because there were stress-related problems in his team. Dave was a senior corporate executive and leader in his industry. He had worked for several Fortune 100 companies, and consulted to senior government officials. His team was one of the stars of the company, but internally, his staff complained more and more about stress, and worked in silos (their own specific issues rather than broader concerns of the team or organization) rather than collaborating to achieve more. He stated that the tension in the leadership team was palpable. As he described the situation, it became clear that Dave tended to emphasize a hub-and-spoke communication approach, preferring to work with individuals rather than the group as a whole. In addition, two of his direct reports saw themselves as heirs to his position, and disagreed frequently over issues both substantive and trivial. As a result, his team leaders were more aligned with their own teams than they were with his leadership team. He cited the interpersonal factors that led to this competition, and the group processes that led to two-way rather than multiway communication. His coach gave him suggestions about how to move toward and emphasize a networked communication approach (e.g., asking questions, avoiding weighing in until late in

the discussion), and talked about ways to make the conflict more constructive and facilitative. Dave implemented several changes that established a clearer leadership structure and hierarchy, and fostered a stronger alliance within the leadership team as a whole. After six months of work, Daves team was running on all cylinders again. He then began to turn his attention to ways to improve the company as a whole, which the CEO had encouraged him to do. He used his consultant to help clarify the risks, benefits, opportunities, and challenges of various initiatives, and worked with him to maintain the more adaptive team structure and relationships.

Restorative Coaching

A great deal of clinical and counseling work focuses on helping individuals to reestablish their balance, equilibrium, and adaptability when they encounter temporary disruptions in their lives. Short-term counseling around stress management, positive and negative life changes, coping with separation and loss, restoring emotional strength, and developing new, adaptive coping strategies is central to short-term psychotherapy (e.g., Budman & Gurman, 1988). Restorative coaching provides the same type of help to individuals and teams experiencing difficulties in the business world. The goal of restorative coaching is to help a valued and competent employee or high-functioning team return to former high levels of performance after experiencing short-term difficulties due to changes in people, roles, responsibilities, or finances. Executives are deeply affected by events in their business and personal lives. They experience a great deal of stress due to work pressures, personal demands, travel schedules, competition, and the like (Lowman, 1993). When one or more of these factors becomes overwhelming, the executive can lose his or her edge, forgetting newly honed skills and resorting to older, less effective patterns of behavior. The same thing can happen to this leaders high-performing team. In these cases, the intervention may be as simple as reminding the executive what the core competencies are, and helping the executive to remember how they have handled similar situations in the past. Alternatively, conducting an offsite workshop focusing on business issues like strategic planning or interpersonal issues such as collaboration or teamwork can help the executives team restore their team skills and trigger more effective strategies to achieve the desired organizational performance. Case example. John was an executive who encountered difficulty creating a high-functioning team. He had an excellent reputation, and had been brought to the company by a person who knew and valued his work from previous companies. To everyones surprise, however, he was unable to move his team in the right direction. Some of his peers were uncomfortable with his style and created obstacles to collaboration. His direct reports were accustomed to a great deal of autonomy and expressed frustration with his desire to be more closely involved in their decisions. His coach conducted a detailed interview with the client, and a rapid 360 assessment and personality evaluation to determine the severity and depth of the problems. Based on these results, it became apparent that John had little interest in or facility with detail and administration, preferring the more creative aspects of his work. He became overwhelmed with the administrative and personnel tasks of his new position and as a result he was unable to imple-

250

BERMAN AND BRADT

ment the management skills he had known and used for years. His peers were frustrated that he didnt take care of the mundane business tasks, as the culture of the company was one that emphasized these jobs. The coach provided individual feedback and coaching to help him remember the importance of human capital management (i.e., taking care of his people). The coaching sessions helped him to recall the methods used by his favorite supervisor/mentor, and apply those techniques in his current position. He began to meet others expectations, which made them more open to collaborating. The coach then facilitated a set of directive strategic planning and accountability exercises with his team to help them get back on track with regard to his marching orders. As a result, John was better able to connect with, encourage and lead his team in a positive direction. He reengaged and reinvigorated his team, and led them to meet their goals for several quarters. This process took less than two months, and resulted in a substantial improvement in the individuals performance both with his subordinates and in the eyes of his peers and superiors.

Developmental Coaching

One of the most common forms of coaching, and the one with which clinical psychologists are most often involved, is what we have called developmental coaching. This approach deals with individuals who have substantial difficulties in some aspect of their management style, but for a variety of reasons are able to retain their jobs. In some instances, these individuals are high producers. Success in most segments of the business world depends, first and foremost, on the ability to boost revenues and drive sales. In sections of the business where revenues are not part of the equation, achieving the goals set by the organization (decrease expenses, increase market share, retain talent, etc.) is the essential success factor. Individuals who excel in these domains are tremendously valuable to a corporation, and will likely move higher in the organization despite weaknesses or challenges in management and interpersonal spheres. Often, highly successful business people rise in the organization based on their business savvy and technical abilities, and later they or their peers or superiors find out that they lack some of the soft-side skills they need to succeed at these higher levels. In more dire situations, individuals with superior capabilities in the business domain self-destruct because of an inability to perform critical human interaction skills. Developmental coaching is designed to identify and address skills deficits, and remove psychological and organizational barriers to performance (production deficits) in individuals who offer a substantial benefit to the organization. In severe cases, these individuals are known as competent jerks (Casciaro & Lobo, 2005). In most cases they are individuals with self-limiting personality characteristics or behavior patterns. In our experience, the most common problem is poorly controlled anger. The types of presenting problems run the gamut, however, including provocative or impatient behavior, passive-aggressive characteristics, inattention to administrative or structural issues, and sometimes narcissistic or histrionic characteristics. At times these individuals seek coaching on their own. More often, however, a supervisor or HR generalist refers them because they see their value but are having difficulty removing the obstacles. I spent 15 years learning how to confront people, challenge assumptions, and push for my ideas, said a senior attorney who

had recently been promoted to vice president and general counsel of a publicly traded company. Now, Im supposed to listen, negotiate, and collaborate. I have to learn a whole new set of skills. Many executives lack skills or fail to perform well on one or more soft-side skills such as communication and listening, emotion regulation, providing encouragement and support (e.g., positive reinforcement), and showing sensitivity and tact with others. Others lack some business skills such as structuring organizations and teams or problem solving and decision making. Still others need help integrating these core skills into the more complex leadership competencies, such as strategic vision and planning, building and aligning teams and matrices, driving performance and accountability, and developing people (Office of Personnel Management, 1998). Individuals lacking in emotional intelligence are often part of this group of individuals (Goleman, 1998). Some have skills deficits, never having learned these tools and abilities in the first place. Others have production deficits, in that they are able to use these skills in other life settings or in work settings in the past, but not in the current workplace. Developmental coaching is the most familiar approach for psychologists, and has been described in a number of books and journals (Diedrich, 1996; Kilburg, 2000, 2004). Many case examples are available in the literature, so we will not provide one here. The developmental approach tends to use many of the theories, skills and techniques used in more traditional clinical interventions. The cognitive behavioral framework to developmental coaching works to identify core beliefs, cognitive distortions, and internal dialogues that create obstacles to successful performance (Ducharme, 2004; Sherin & Caiger, 2004). Psychodynamically oriented coaches (e.g., Kilburg, 2000, 2004) use the executives past experience plus clinical insight to identify emotional and representational barriers to achieving the expected goals. Kilburg (2000) has argued that individuals may repeat in business settings some of the dynamics they encountered in their family lives. These recurring patterns emerge unconsciously, with the coaching client sometimes inadvertently inducing others to act in the same way their family members acted, creating a recurring cycle of problems and unsuccessful solutions. To the extent that psychological interventions are indicated to help these individuals improve their performance, psychologists are well qualified to deliver these services. Psychologists are at risk, however, for overprescribing developmental coaching rather than facilitative coaching or executive consulting. Since the orientation of many psychologists is to look for problematic mental models, historically linked self-defeating behavior, and other recurring patterns, they are more likely to miss organizational systems and structures that cause the observed problems. Personality assessment also is more likely to lead to recommending developmental coaching, as many practitioners forget that personality style only creates a bias toward certain behaviors, rather than determines those behaviors. Greater knowledge and experience in the business world will help the psychologist detect and identify processes, systems, and structures in the business environment that produce problematic behaviors. There are differences between the delivery of psychological services for clinical problems versus developmental coaching for work-related problems. Logistically, coaching can take place in a wide range of settings, for varying amounts of time, and can rely on a wider range of information sources than can psychotherapy.

SPECIAL SECTION: EXECUTIVE COACHING AND CONSULTING

251

Coaching tends to be more directive and more collegial than psychotherapy, whereas the clienttherapist boundary should be clear and consistent (Kampa-Kokesch & Anderson, 2001). Substantively, coaching (unless sought and paid for by the individual executive) requires an alliance among the company, the individual, and the coach, while psychotherapy with adults must be a dyadic alliance. Coaching also presumes what a successful outcome should be (improved financial performance, greater efficiencies, improved 360 ratings, etc.), while psychotherapy can allow for multiple successful outcomes (e.g., staying married or getting divorced) depending on individual characteristics and circumstances. Lastly, psychotherapy assumes the presence of psychopathology in the form of emotion dysregulation, skills deficits, cognitive distortions, intrapsychic conflicts, or problematic developmentalrelational experiences. It is our experience that the majority of coaching clients do not meet the criteria for Axis I or Axis II American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSMIV) diagnoses. To the extent that psychotherapy is used to address subclinical syndromes or problems in living, however, there will certainly be overlap between developmental coaching and psychotherapy.

to understanding how actions in one part of a corporation can have a significant impact on your client, regardless of what he or she does as an individual or team leader. Leadership and management theories are outside of the base knowledge of many psychologists, but offer critical understandings of business policies and practices. 4. Be very clear about who the client is. In some coaching situations, it is expected that the organization is the client, and the coach is expected to report to a supervisor, an HR generalist, or other company representative. This often makes sense in a situation where the human client, the executive, has trouble understanding how his or her behavior affects others. In this context, the coach, the supervisor and the HR representative work together to bring the executive up to expectations. The trusting relationship is among all the parties, rather than just between the executive and the coach. In other situations, however, the individual executive needs to be the only client, and a confidential and trusting relationship needs to be established. We do not believe there is a single answer for all coaching situations; rather, the decision should be made based on how gains can be achieved and maintained most quickly. In all contexts, confidentiality, collaboration, and the involvement of other people in the coaching relationship must be made explicit at the beginning of the process. Understand the business world. A successful coach who focuses on restorative or developmental coaching need not have an MBA. All coaches, however, need to know and understand the key issues and common terms used in business settings. Jargon is a key element to any discipline, and one cannot be a competent advisor if one doesnt know the language of business. Broadly relevant terms are essential, and familiarity with current business theory and practice is invaluable. Coaches should read the Wall Street Journal and major business journals (e.g., Harvard Business Review) to stay abreast of trends and ideas. In addition, if you have worked in organizations (e.g., hospitals and universities as well as public or private organizations), draw on your experience in those settings. Many of the dynamics and issues are similar if you attend to the business side of those settings. At the client level, an essential part of your assessment includes reading about the company he or she works for to know what the broader issues are. Be clear about the differences between psychotherapy and coaching. In most individual psychotherapies, the boundaries between client and therapist are clear and fixed. In some coaching situations, however, this may not be as important. As we indicated above, collaboration among the client, his or her supervisor or supervisors, and HR representatives can be an important alliance that fosters movement and change. In addition, there are times when the coach may interact socially with the executive and his or her team. For example, both of the authors have had dinner and played golf with their clients. In

Summary and Recommendations

There is a need for executive coaching of all types and plenty of room in the field for individuals with business and clinical expertise. In addition, most coaching assignments are not purely one type. A facilitative coaching assignment can identify developmental weaknesses that will benefit from intervention. A restorative coaching assignment can build a relationship (or a transference) that leads to an ongoing executive consulting situation. Several steps will help in becoming a successful coach, and avoiding potential pitfalls: 1. Capitalize on your strengths. If you do not have business experience, do not represent yourself as having business experience. Focus on those types of coaching assignments that fit with your strengths and competencies. Human resources leaders and executives will respect you more and refer to you again if you turn down or forward an assignment that is not within your expertise. Over time, you may develop enough insight and understanding to work on business focused assignments. Take an active, directive role. These clients for the most part arent interested in a one-sided relationship. They expect their consultants to provide specific guidance and concrete deliverables. If you do not have an answer, say so, but at the least you should have some good questions. Most of the time, however, it is important to inform them what you think they should do or how they should act. Become poly-theoretical. Individual personality theories or treatment theories are by themselves insufficient to help executives in their complex situations (Kilburg, 2000). Cognitive theory and psychodynamic theory help to understand the ways in which an individuals preexisting representational models interfere with adaptation and change. Structural and systems theories are essential

5.

2.

6.

3.

252

BERMAN AND BRADT

off-site team meetings, the coach may need to be both a participant and an observer in socially focused teambuilding activities. Confidentiality and tact, however, remain paramount for the coach regardless of the situation. 7. Be equally clear about the similarities between coaching and psychotherapy. Coaching should have an action plan just as psychotherapy should have a treatment plan. Objective change is important in both cases, although psychotherapy focuses on family or intimate relationships or symptoms, while coaching focuses on business relationships and work performance. Transference relationships are not unique to psychotherapy; the projection of both good and bad characteristics onto a person in a superior or authority position is ubiquitous. Transference affects executives with their subordinates, and coaches with their executive clients (Maccoby, 2004). Coaches need to maintain perspective, humility, and self-awareness to ensure that they continue to be maximally helpful to the client. Conduct individual outcome evaluations for every client. Empirical data on coaching is unlikely to emerge through the channels used for the evaluation of psychotherapy. The target population is unlikely to willingly participate in research studies, and experimental designs will be hard to come by from large corporations or their employees. Methods that have been developed for mental health outcomes (Berman, Rosen, Hurt & Kolarz, 1998) may be useful for executive coaching as well. These techniques include identifying targets for change and assessing those targets at the beginning and end of the intervention, followed by data aggregation using individual change statistics. While this approach will never demonstrate the efficacy of coaching, it will provide data on the effectiveness of coaching in certain circumstances or for certain populations. Continue to build your skills. It is important to build your area of expertise with the help of study, supervision, and collaboration. The first author still works with and receives supervision from senior business executives and two I/O psychologists who have worked in business for more than 20 years. The second author organizes and conducts twice-yearly retreats to help his team of line managers and organizational consultants hone their skills and insights. The business world changes, and it is essential that coaches of all sorts stay abreast of those changes.

8.

9.

There are many reasons why clinical psychologists move toward the corporate world. The shift is reasonable and achievable, but requires effort and training. One cannot become a coach by will alone, or solely by completing a doctorate. The yield is worthwhile, and opens doors that many find worth the effort.

References

Argyris, C. (1990). Overcoming organizational defenses: Facilitating organizational learning. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Berglas, S. (2002). The very real dangers of executive coaching. Harvard Business Review, 80, 8792. Berman, W. H., Rosen, C., Hurt, S. W., & Kolarz, C. (1998). Toto, were not in Kansas anymore: A conceptual framework for outcomes assessment and management. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5, 115133. Bradt, G., Check, J. & Pedraza, J. (2006). The new leaders hundred day action plan. New York: Wiley. Brotman, L. E., Liberi, W. P., & Wasylyshyn, K. M. (1998). Executive coaching: The need for standards of competence. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 50, 40 46. Buckingham, M., & Clifton, D. O. (2001). First, discover your strengths. New York: Free Press. Budman, S. H., & Gurman, A. S. (1988). Theory and practice of brief psychotherapy. New York: Guilford Press. Casciaro, T., & Lobo, M. S. (2005). Competent jerks, lovable fools, and the formation of social networks. Harvard Business Review, 83(6), 9299. Collins, J. (2001). Good to great. New York: HarperCollins. Diedrich, R. C. (1996). An iterative approach to executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 48, 61 66. Ducharme, M. J. (2004). The cognitive behavioral approach to executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal, 56, 214 224. Fisher, A. (2005, March 7). Starting a new job? Dont blow it. Fortune, 151(5), 48 51. Fisher, A. (1998, June 22) Dont blow your new job. Fortune, 137(6), 3,162163. Gegner, C. (1997). Coaching: Theory and practice. Unpublished masters thesis, University of San Francisco, California. Goleman, D. (1998). Working with emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books. Hall, D. T., Otazo, K. L., & Hollenbeck, G. P. (1999). Behind closed doors: What really happens in executive coaching. Organizational Dynamics, 27(3), 39 52. Hays, K. F., & Brown, C. H. (2003). Youre on! Consulting for peak performance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Kampa-Kokesch, S., & Anderson, M. Z. (2001). Executive coaching: A comprehensive review of the literature. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 53, 205228. Kilburg, R. R. (2000). Executive coaching. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Kilburg, R. R. (2004). Trudging toward Dodoville: Conceptual approaches and case studies in executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal, 56, 203213. Laske, O. E. (1999). Transformative effects of coaching on executives professional agenda, 1. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Lencione, P. (2002). The five dysfunctions of a team. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Lowman, R. (1993). Counseling and psychotherapy of work dysfunctions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Maccoby, M (2004). The power of transference. Harvard Business Review, 82(9), 76 85. McCune, J. C. (1999). Sorry, wrong executive. Management Review, 88, 1521. Office of Personnel Management. (1998). MOSAIC Competencies: Leadership update study 1998. http://www.opm.gov/deu/Handbook_2003/ DEOH-MOSAIC-5.asp Peterson, D. B. (1996). Executive coaching at work: The art of one-on-one change. Consulting Psychology Journal, 48, 78 86. Peterson, D. B., & Sokol, M. B. (2005, April 1517). Coaching leaders around critical choices. Paper presented to the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Los Angeles. Richard, J. T. (2003). Ideas on fostering creative problem solving

SPECIAL SECTION: EXECUTIVE COACHING AND CONSULTING in executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal, 55, 249 256. Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline. New York: Currency Doubleday Senge, P. M., Kleiner, A., Roberts, C., Ross, R. B., & Smith, B. J. (1994). The fifth discipline fieldbook. New York: Currency Doubleday. Sherin, J., & Caiger, L. (2004). Rational emotive behavior therapy: A behavioral change model for executive coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal, 56, 225233. Sherman, S., & Freas, A. (2004). The wild west of executive coaching. Harvard Business Review, 82(11), 8290.

253

Stern, L. S. (2004). Executive coaching: A working definition. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 56, 114. Velsor, E. V., Leslie, J. B., & Fleenor, J. W. (1997). Choosing 360 A guide to evaluating mult-rater feedback instruments for management development. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Received September 9, 2005 Revision received November 22, 2005 Accepted December 22, 2005

Você também pode gostar

- The Coaching Connection: A Manager's Guide to Developing Individual Potential in the Context of the OrganizationNo EverandThe Coaching Connection: A Manager's Guide to Developing Individual Potential in the Context of the OrganizationAinda não há avaliações

- Four Essential Ways that Coaching Can Help ExecutivesNo EverandFour Essential Ways that Coaching Can Help ExecutivesAinda não há avaliações

- Core Management Principles: No Flavors of the MonthNo EverandCore Management Principles: No Flavors of the MonthAinda não há avaliações

- Making It in Management: Developing the Thinking You Need to Move up the Organization Ladder … and Stay ThereNo EverandMaking It in Management: Developing the Thinking You Need to Move up the Organization Ladder … and Stay ThereAinda não há avaliações

- Organizational Coaching: Building Relationships and Programs That Drive ResultsNo EverandOrganizational Coaching: Building Relationships and Programs That Drive ResultsAinda não há avaliações

- Strategic Leadership for Sustainable Personal and Organizational SuccessNo EverandStrategic Leadership for Sustainable Personal and Organizational SuccessAinda não há avaliações

- Aligned Leadership: Building Relationships, Overcoming Resistance, and Achieving SuccessNo EverandAligned Leadership: Building Relationships, Overcoming Resistance, and Achieving SuccessAinda não há avaliações

- Handbook for Strategic HR - Section 3: Use of Self as an Instrument of ChangeNo EverandHandbook for Strategic HR - Section 3: Use of Self as an Instrument of ChangeAinda não há avaliações

- GUIDE TO BECOMING AN EFFECTIVE MANAGER: Thoughts For ConsiderationNo EverandGUIDE TO BECOMING AN EFFECTIVE MANAGER: Thoughts For ConsiderationAinda não há avaliações

- Business-Focused HR: 11 Processes to Drive ResultsNo EverandBusiness-Focused HR: 11 Processes to Drive ResultsNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (3)

- Executive Coaching for Results: The Definitive Guide to Developing Organizational LeadersNo EverandExecutive Coaching for Results: The Definitive Guide to Developing Organizational LeadersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (2)

- Finding Your Management Style: What It Means to You and Your TeamNo EverandFinding Your Management Style: What It Means to You and Your TeamAinda não há avaliações

- HBR Guide to Coaching Employees (HBR Guide Series)No EverandHBR Guide to Coaching Employees (HBR Guide Series)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (7)

- Enhancing 360-Degree Feedback for Senior Executives: How to Maximize the Benefits and Minimize the RisksNo EverandEnhancing 360-Degree Feedback for Senior Executives: How to Maximize the Benefits and Minimize the RisksNota: 1 de 5 estrelas1/5 (1)

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Managing People (with featured article "Leadership That Gets Results," by Daniel Goleman)No EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Managing People (with featured article "Leadership That Gets Results," by Daniel Goleman)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (15)

- The Pro-Achievement Principle: Cultivate Personal Skills for Effective TeamsNo EverandThe Pro-Achievement Principle: Cultivate Personal Skills for Effective TeamsAinda não há avaliações

- The Adventure of Self-Coaching: Discover and tap your full potentialNo EverandThe Adventure of Self-Coaching: Discover and tap your full potentialAinda não há avaliações

- Got a Solution?: HR Approaches to 5 Common and Persistent Business ProblemsNo EverandGot a Solution?: HR Approaches to 5 Common and Persistent Business ProblemsAinda não há avaliações

- People Fusion: Best Practices to Build and Retain A Strong TeamNo EverandPeople Fusion: Best Practices to Build and Retain A Strong TeamAinda não há avaliações

- Preventing Derailment: What To Do Before It's Too LateNo EverandPreventing Derailment: What To Do Before It's Too LateAinda não há avaliações

- Becoming a Leader Coach: A Step-by-Step Guide to Developing Your PeopleNo EverandBecoming a Leader Coach: A Step-by-Step Guide to Developing Your PeopleNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- Leadership Coaching: When It's Right and When You're ReadyNo EverandLeadership Coaching: When It's Right and When You're ReadyAinda não há avaliações

- Grow Through Disruption: Breakthrough Mindsets to Innovate, Change and Win with the OGINo EverandGrow Through Disruption: Breakthrough Mindsets to Innovate, Change and Win with the OGIAinda não há avaliações

- Becoming a Leader in Product Development: An Evidence-Based Guide to the EssentialsNo EverandBecoming a Leader in Product Development: An Evidence-Based Guide to the EssentialsAinda não há avaliações

- Leadership Excellence: Creating a New Dimension of Organizational SuccessNo EverandLeadership Excellence: Creating a New Dimension of Organizational SuccessAinda não há avaliações

- Defining HR Success: 9 Critical Competencies for HR ProfessionalsNo EverandDefining HR Success: 9 Critical Competencies for HR ProfessionalsNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- Applying Critical Evaluation: Making an Impact in Small BusinessNo EverandApplying Critical Evaluation: Making an Impact in Small BusinessAinda não há avaliações

- Mastering the Art of Management: A Comprehensive Guide to Becoming a Great ManagerNo EverandMastering the Art of Management: A Comprehensive Guide to Becoming a Great ManagerAinda não há avaliações

- The Simple Side Of Human Resource Management: Simple Side Of Business Management, #1No EverandThe Simple Side Of Human Resource Management: Simple Side Of Business Management, #1Ainda não há avaliações

- Research Paper: The Effect of Coaching On Leadership Awareness and ResponsibilityDocumento14 páginasResearch Paper: The Effect of Coaching On Leadership Awareness and ResponsibilityInternational Coach AcademyAinda não há avaliações

- Transformational and Transactional Leadership in Mental Health and Substance Abuse OrganizationsNo EverandTransformational and Transactional Leadership in Mental Health and Substance Abuse OrganizationsAinda não há avaliações

- The Affirmation Principle: How Effective Leaders Bring out the Best in PeopleNo EverandThe Affirmation Principle: How Effective Leaders Bring out the Best in PeopleAinda não há avaliações

- Breakthrough Leadership: How Leaders Unlock the Potential of the People They LeadNo EverandBreakthrough Leadership: How Leaders Unlock the Potential of the People They LeadAinda não há avaliações

- Leadership Breakthrough: Leadership Practices That Help Executives and Their Organizations Achieve Breakthrough GrowthNo EverandLeadership Breakthrough: Leadership Practices That Help Executives and Their Organizations Achieve Breakthrough GrowthAinda não há avaliações

- Build Your Organization from the Inside-out: Developing People Is the Key to Healthy LeadershipNo EverandBuild Your Organization from the Inside-out: Developing People Is the Key to Healthy LeadershipAinda não há avaliações

- Free Range Management: How to Manage Knowledge Workers and Create SpaceNo EverandFree Range Management: How to Manage Knowledge Workers and Create SpaceAinda não há avaliações

- Developmental Leadership: Equipping, Enabling, and Empowering Employees for Peak PerformanceNo EverandDevelopmental Leadership: Equipping, Enabling, and Empowering Employees for Peak PerformanceAinda não há avaliações

- Being the Leader They Need: The Path to Greater EffectivenessNo EverandBeing the Leader They Need: The Path to Greater EffectivenessAinda não há avaliações

- E+M+F = Formula for Successful Organizational LeadershipNo EverandE+M+F = Formula for Successful Organizational LeadershipNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (1)

- A Powerful Team: How Ceos and Their Hr Leaders Are Transforming OrganizationsNo EverandA Powerful Team: How Ceos and Their Hr Leaders Are Transforming OrganizationsAinda não há avaliações

- Ink & Insights: Mastering Business Coaching in the Digital AgeNo EverandInk & Insights: Mastering Business Coaching in the Digital AgeAinda não há avaliações

- Peaceful Leadership: Tools and Techniques for Fostering Psychological Safety, Trust, and Inclusion in Your OrganizationNo EverandPeaceful Leadership: Tools and Techniques for Fostering Psychological Safety, Trust, and Inclusion in Your OrganizationAinda não há avaliações

- Summary of The Advantage: by Patrick Lencioni | Includes AnalysisNo EverandSummary of The Advantage: by Patrick Lencioni | Includes AnalysisNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1)

- Leadership in the Hood: Talking About Leadership Application and Management Issues in OrganisationsNo EverandLeadership in the Hood: Talking About Leadership Application and Management Issues in OrganisationsAinda não há avaliações

- Research Paper Topics On Organizational BehaviorDocumento5 páginasResearch Paper Topics On Organizational Behaviorh00yfcc9100% (1)

- Talent Conversation: What They Are, Why They're Crucial, and How to Do Them RightNo EverandTalent Conversation: What They Are, Why They're Crucial, and How to Do Them RightAinda não há avaliações

- PT BMI Presentation-17.02.2016Documento55 páginasPT BMI Presentation-17.02.2016Bayumi Tirta JayaAinda não há avaliações

- SAP PM Tables and Related FieldsDocumento8 páginasSAP PM Tables and Related FieldsSunil PeddiAinda não há avaliações

- Accounting Crash CourseDocumento7 páginasAccounting Crash CourseschmooflaAinda não há avaliações

- Mobike and Ofo: Dancing of TitansDocumento4 páginasMobike and Ofo: Dancing of TitansKHALKAR SWAPNILAinda não há avaliações

- 810 Pi SpeedxDocumento1 página810 Pi SpeedxtaniyaAinda não há avaliações

- 1.supply Chain MistakesDocumento6 páginas1.supply Chain MistakesSantosh DevaAinda não há avaliações

- Ejb3.0 Simplified APIDocumento6 páginasEjb3.0 Simplified APIRushabh ParekhAinda não há avaliações

- Far 7 Flashcards - QuizletDocumento31 páginasFar 7 Flashcards - QuizletnikoladjonajAinda não há avaliações

- Ezulwini Reinsurance Company ProfileDocumento17 páginasEzulwini Reinsurance Company ProfileAnonymous fuLrGAqg100% (2)

- P02-Working Cash Advance Request FormDocumento30 páginasP02-Working Cash Advance Request FormVassay KhaliliAinda não há avaliações

- Brief Overview of APPLDocumento2 páginasBrief Overview of APPLRashedul Islam BappyAinda não há avaliações

- Intellectual Capital Is The Collective Brainpower or Shared Knowledge of A WorkforceDocumento3 páginasIntellectual Capital Is The Collective Brainpower or Shared Knowledge of A WorkforceKatherine Rosette ChanAinda não há avaliações

- Market Penetration of Maggie NoodelsDocumento10 páginasMarket Penetration of Maggie Noodelsapi-3765623100% (1)

- MCS in Service OrganizationDocumento7 páginasMCS in Service OrganizationNEON29100% (1)

- Japanese YenDocumento12 páginasJapanese YenPrajwal AlvaAinda não há avaliações

- DO-178B Compliance: Turn An Overhead Expense Into A Competitive AdvantageDocumento12 páginasDO-178B Compliance: Turn An Overhead Expense Into A Competitive Advantagedamianpri84Ainda não há avaliações

- SAP SD Functional Analyst ResumeDocumento10 páginasSAP SD Functional Analyst ResumedavinkuAinda não há avaliações

- Dev EreDocumento1 páginaDev Ereumuttk5374Ainda não há avaliações

- Counter-Brand and Alter-Brand Communities: The Impact of Web 2.0 On Tribal Marketing ApproachesDocumento16 páginasCounter-Brand and Alter-Brand Communities: The Impact of Web 2.0 On Tribal Marketing ApproachesJosefBaldacchinoAinda não há avaliações

- Oracle Applications Knowledge Sharing-Ajay Atre: OPM Setup in R12Documento23 páginasOracle Applications Knowledge Sharing-Ajay Atre: OPM Setup in R12maniAinda não há avaliações

- RTHD L3gxiktDocumento2 páginasRTHD L3gxiktRobin RahmanAinda não há avaliações

- FEBRUARY 2020 Surplus Record Machinery & Equipment DirectoryDocumento717 páginasFEBRUARY 2020 Surplus Record Machinery & Equipment DirectorySurplus RecordAinda não há avaliações

- Rosenflex BrochureDocumento32 páginasRosenflex Brochuresealion72Ainda não há avaliações

- Session 4-11.8.18 PDFDocumento102 páginasSession 4-11.8.18 PDFTim Dias100% (1)

- International Mining January 2018Documento80 páginasInternational Mining January 2018GordAinda não há avaliações

- TOYOTA - Automaker Market LeaderDocumento26 páginasTOYOTA - Automaker Market LeaderKhalid100% (3)

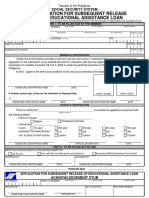

- Application For Subsequent Release of Educational Assistance LoanDocumento2 páginasApplication For Subsequent Release of Educational Assistance LoanNikkiQuiranteAinda não há avaliações

- G O Ms No 281Documento3 páginasG O Ms No 281HashimMohdAinda não há avaliações

- Books of PDocumento13 páginasBooks of PicadeliciafebAinda não há avaliações