Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

John Micklethwait Is Documented@Davos Transcript

Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

John Micklethwait Is Documented@Davos Transcript

Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

John Micklethwait is Documented@Davos Transcript Documented@Davos 2012

NICK: Hello, I'm here at documented@DAVOS. I'm Nick Hilton, I'm the technology reporter for The New York Times and a columnist on the Bits blog. And I'm here with Trip Adler who is the co-founder and CEO of Scribd. And I'm also here with John Micklethwait who is the editor in chief of The Economist.

JOHN: Thank you.

NICK: How is your DAVOS going so far, Trip?

TRIP: It's great. I just got in last night. I've been having a little bit of trouble navigating with all the snow, but it's been excellent to be here. This is my second year attending, and it's just great to get outside Silicon Valley and interact with a lot of people just from different countries and different backgrounds, and just get a broader perspective on what's happening in the world.

NICK: And yours, John?

JOHN: It's going well. Slightly--

NICK: Is this your first?

JOHN: No, it's my fifth. I always look on DAVOS as a version of speed dating. You see a lot of people very quickly. But it is very efficient.

NICK: Have you met your significant other yet on here?

JOHN: Sadly, I'm already married. That's always a possibility.

NICK: So as someone who has been here five times, have you seen a lot of changes as far as the way technology has become a part of the discussion here?

JOHN: Yes, technology every year gets bigger. And every year you see technology gradually pushing into more bits. There are cleverer ways, cleverer gizmos to do things. And each time, on the whole, pretty much every DAVOS I've been to, the optimism has pretty much always come from Trip's region, it's come from Silicon Valley. Even when things were awful in 2008, you could go and see Google, and they gave you at least a slice of optimism.

NICK: So, Trip, we were talking earlier about the future of reading and devices and all that fun stuff. How do you feel about where technology and reading is today compared to where it was maybe even last year?

TRIP: I think it's evolved quite a bit in the last year. We went through a tremendous period of change in the reading space. I mean, just with the new devices coming out, the impact social is having on reading, the way apps are becoming great for reading, better than web browsers. There's been a lot of change taking place. But at the same time, I think we're still very early in the evolution of reading. You've seen huge transformations happen in music and in video. But on the reading side of things, I think we're still much earlier. It's almost kind of like the pre-iTunes era. I think we're going to see just a lot more change in the next decade or so.

NICK: What do you mean by the pre-iTunes era? Are we waiting for an iTunes for reading, or--

TRIP: I think we are. Right now reading is very fragmented, right? There's a number of different formats people are reading on, there's a number of different devices. People are going to individual publishers and have completely different experiences. And I think over time, you're going to see these different experiences aggregate in a more unified experience. So it will be kind of like an iTunes of reading, or a Spotify or Netflix of reading.

NICK: With The Economist, you guys have an iPad app that I believe has been pretty successful, right?

JOHN: Yes.

NICK: Do you approach your editorial differently when you're writing or creating for the iPad experience or for the print experience?

JOHN: No. That's a very good question, though. Basically, I think that something big has happened in terms of the method of distribution. That is a big and a seismic change. Suddenly, you've got one in front of you. It's a way of receiving things.

And what really struck us is, when I became editor, five or six years ago, I worried that there was this hurricane coming through which would hit newspapers including The New York Times and push through, was bound to hit magazines as well. And that was the internet. Actually, it turned out that the web wasn't quite the same as a magazine experience. And the web was something very much people led forward. They wanted to grab things quickly, to snack.

By contrast, magazines were much more leaning back. And one of the things which first really tipped us off about the iPad was when we looked at the ads, you suddenly saw all these people lying on beds and things, and you could look at the soles of their shoes. And they were consuming it much more in the way that you would read a magazine. They seemed to be taking a long time to do it.

NICK: So it wasn't a consumption device?

JOHN: I think it's more than that, Actually, it's a new way of doing it. I think the big thing that has changed is all the technology, and these new ways of being able to get things. And that, from our point of view, is nothing but good. The more people I can persuade to pay to read The Economist on a weekly basis, the better.

NICK: So did you just say, as a print experience, that the iPad is actually a better experience?

JOHN: Well, they vary. You have odd people. I saw Jimmy Carter a couple months ago. He said that in every week he now gets The Economist, reads it at Thursday lunchtime in planes, but keeps some stuff to actually get when the print edition comes. You can vary between the two. In some ways, yes is it's quicker, it's certainly quicker in terms of distribution. But I think many people will still want the print.

What's similar, though, is the experience. Well, the way we've done it so far is we've kept the print edition and the iPad completely the same. So therefore, there's a tiny bit extra on the iPad, you can have an audio version so people can listen to it. But effectively, we're saying that's the same experience. You can sit and read it the same way.

The big thing which I think hasn't changed, and which we began to talk about, is reading. Like all these things, you sit and you imagine all these different forms of content, which is what you first asked me about.

Actually, look at what people are doing, what serious people are doing with these new devices. In the end, they're using it a helluva lot to read.

Reading still seems to be the most efficient way for people to take in large amounts of information. I can show you an info-graphic and that's fantastically good. I can show you a bit of video, you could look and see what's happening in wars in Libya very, very quickly. But if you want to get a full picture of what's happening, reading is still actually, I think, still the best way.

NICK: So, Trip, what do you think? Do you think that we're just kind of recreating print experiences on digital devices and we haven't taken it to where it should be yet? What are your thoughts?

TRIP: Well, first of all, I just want to agree that reading is an extremely important form of communication. It's been one of the most important forms of communication for thousands of years, and I think that's still going to be the case going forward. It's both how really complex ideas get communicated-- that's how, I think, a lot of us learned a lot of what we know-- and it's also just a very efficient way to learn things.

I know these days when I see a video online, I often try to look for the transcript immediately, because it's just the quickest way to take in all the information. And I think in the last few years, the way the web has been evolving, it's been leaning toward more short form communication. 140 characters or less.

And I think iPads, Kindles and some of these changes happening are a step towards more long form reading happening. And I think that as the technology gets better, you'll just see even more long form reading happening. So I'm hopeful that we can get people in the world to read more just by creating better reading technology.

NICK: Well, but one of the things with these is, with a lot of experiences with newspapers, with magazines, with books, you're literally just taking the thing that was in the print experience and putting on here. Sure, sometimes you're adding video, you're adding audio and graphics. But what is, five years from now when we have flexible displays or however long it takes. What is the experience? Is it still that? Or is it something--

TRIP: I guess I didn't answer your question, did I? So right now, it's very fragmented right? You have PDFs, you have EPUBs, you have web pages, you have ad base reading experiences, you have experiences customized for different devices. And I think, over time, we're going to see all of those merge a bit more. It doesn't make sense to read PDFs for one thing and web pages for another. So I think those are going to merge.

And I actually think that that merging of different types of reading formats will extend to other forms of media too. It sounds a little bit crazy, but you can start to merge a video and a document, or an audio file and images, right? I mean, that's part of what we're doing with this video here is, we're going to take the transcript and upload it to Scribd and combine those two together. So I think you're going to see all these different media types merge.

And Scribd as a company, we start out with this idea of trying to merge documents and web pages. So we started out with wanting to make PDFs more easily readable on the web. So the first step was to take a PDF and make it easily readable in Flash in a web browser. Then we went to HTML 5. And the next step is we're working on making documents reflowable. So actually, breaking down the fixed structure of a document and pretty much making it just like a web page.

NICK: So you can resize the page and it will reflow and things will--

TRIP: Exactly. So you can just pinch to zoom and the text will wrap. So, as opposed to zooming in, and zooming in a particular point on a PDF and having to move back and forth with your finger, it'll actually just wrap to fit the size of the screen, which is how a web page works.

NICK: Where does social fit into all this? If you look at a device like this, you can't tell, or I can't tell for the most part, if I'm reading a book or a magazine article, or whatever. They all look the same. But certain things I can comment on, certain things I can't. How does that fall into books, I guess, in the future?

JOHN: I think it's very difficult. At the moment, I suspect, the two are going to merge. There's going to be more of it. I think you're going to see more people at the moment who are just putting out a print version having social stuff around it and vice versa. But it's early days very much, as Trip was saying.

And the reason why I banged on about reading is because immediately, from an editor's point of view, what are you producing? The content, just the same as you, is that you sit there and you see this and you think the technology will change the sort of content we need to do. And actually, weirdly, I think with the web it did. You suddenly had to go much more towards blogs, social media swept in.

You might have to do the same with mobile phones and stuff like that. But the basic tablet experience doesn't seem to go that far down. People seem to be using it a lot of the time just to read. They might use it also as a television some of the time. They might use it as an email device. But when they're actually trying to absorb information, they seem to be in that area. And so it's a mixture between.

As an editor, you have to spend a vast amount of time being paranoid about this, because you'd be mad. I don't regret being paranoid about what the web could have done to us five years ago, because good things came from that, even if I was probably wrong about it. You should be paranoid about it. But at the moment, you have to also just think how people use these things, what they're doing with it.

NICK: Do you worry about the business models of this?

JOHN: I'm happy with the business model that we have, which is basically we will deliver things on the iPad as long as you pay for it. That's the center of it. The basic--

NICK: You mean people have to give you money to read things?

JOHN: Exactly. That's the strange and bananas world in which we try to live. And I think that is different to the web model where you do things like metering and so on. As long as you keep those two together, you're OK.

But the basic underlying premise-- and I think this is something that the media as a whole have to take on-is if you have content, you have to try and make that content good enough for people to pay for it. And it they pay for it, then you can start getting advertising and things behind.

NICK: Trip, do you think there will be more books, for example, that will be advertising based? Or other business models that you can potentially see for content online? And on iPads and things like that?

TRIP: Yeah, well, fortunately, there have been some pretty effective business models just in the last few years on the iPad. But I think that as things evolve and as more sophisticated platforms develop with a better user experience, we are just going to be able to try even more business models. So ones that I'm thinking about are, yeah, ads in books. I think that's definitely a potential one.

One that I'm really excited about is a subscription model. Right? You've seen that working extremely well for video on Netflix. It's now working for music, through Spotify--

NICK: So what's that, a subscription model for all kinds of reading content? Or books in particular, or what?

TRIP: I think it could be for all kinds. It could be one subscription for all the books you want to read, for all the magazines, all the news, and anything you--

JOHN: In many ways, what you're saying is old ideas kind of being reinvented. Because that's sort of like a book club, which was the way in which books spread. And again, Spotify in some ways is like the old music clubs which, when I was a sad teenager in the 1970s, you used to get LPs through. Everyone's trying in the same way to try to get money at the end of it. And basically, the more stable and secure your revenue source, the happier you are.

NICK: I'm sure you hear this question all the time, but you guys don't have bylines in The Economist. When you look at how a lot of people now are-- me for example, I distribute my articles on Twitter and Facebook and all these things. And contract it, it brings a tremendous amount of readers. And people follow me for technology reporting and business reporting and so on. Have you guys explored the idea of kind of identifying some reporters there? Or--

JOHN: What we do is, on the web, largely we've moved towards blogs as a way of keeping up with the news. And there we do it-- you could argue, it's a halfway house-- through initials. And the main reason why is we do want to keep some element of that anonymity. But it makes no sense at all if you don't-- if one Economist writer, initials NP, is saying something, then at least you know it's him rather than somebody else.

And then you've got the columnists on top, they also have their blogs. So there's a sort of slight halfway land. And I'm sure you can come up with lots of logical reasons why it doesn't fit into one camp or the other. But in practice, it seems to work quite well.

In terms of Twitter, Twitter has been fantastically successful for us. And Facebook, as you know, we're one of the biggest people there in terms of the number of people who follow us.

TRIP: I agree that social is going to become an increasingly important part of reading. All kinds of reading, ranging from news to books to magazines. You've already seen it in the last few years. A lot of my personal discovery of content is through the social web, and I think that's just going to continue.

And as people share more and more, it's going to become a more and more important way of discovering content. So we're actually starting to experiment with a passive sharing model, where everything you read gets shared. This has been very successful with The Washington Post.

NICK: That sounds a little scary, though.

TRIP: It is. And that's why we've only rolled it out to a separate product, not to the same product. We have a separate product called flow that's designed just for news and blog content. We have an option there where everything you read gets automatically shared. And what it does is, it really encourages people to share a lot more. But it also makes the discovery much more interesting. So we're currently experimenting--

JOHN: Don't you self-censor your discovery process? You think, I can't read that, cause everyone might see this.

TRIP: Well, you don't have to. You can opt out of an article if you choose to. But I do think it has interesting potential.

NICK: I think it definitely has an interesting potential, but I think that what you need to have with that is something where you kind of detect that maybe this is an article that you probably don't want to share, and you check with the user. Like if it's something political or whatever it is that you think could be a hot topic.

But, I mean, I think it is a great idea. I'd love to be able to follow my friends around the web as they read different things, but I also wouldn't want to find out that somebody was looking up something about an STD or something like that.

JOHN: It's your inner CIA aspect.

NICK: Exactly.

JOHN: One of the difficulties for media is that you have this problem. You can not be everything, you can not. I mean, you look at The New York Times. It's a huge organization, it does a huge amount of stuff. But all the same, it doesn't do everything. And that I think is a real issue.

For instance, you brought up our journalists. We have 150 editorial staff, roughly. Sure, you can get them involved in social media. And a lot of them use social media as a way of researching stuff, the younger ones particularly.

But actually, what we've discovered a bit is, as long as you have a very intelligent audience following you-which is what we do have, I think-- is that what tends to happen is we write an article. And then this debate starts with these people arguing with each other. And yes, sometimes the journalists go in, but not--

In the end, people, I think, come to us because they want to know what we think about things, and then they'll argue about it. The idea of recruiting another 100 journalists just to keep part of that discussion, I don't think really pays off for what we do. And we might be a very narrow version of it, but that still is the core of what we do. We provoke. We make people angry. We make people happy, sad, whatever. And then they start discussing it.

NICK: So let's fast forward five years from now. We're back at DAVOS and I'm sitting here with the iPad 12 which is embedded in my hands or something like that. What is this reading experience? What does Scribd look like then?

TRIP: I'd say there's a few main themes that we're pursuing over the next few years. So far we've started with this simple idea of letting any kind of person or organization take a document, upload it to the web, convert it to a web page. But that's just the first piece of a larger ecosystem we want to build.

So the next big steps for us are, one, mobile, taking all this content, making it easily readable on any device you want, anywhere you want to read.

The second is what we call verticalizing Scribds. A Scribd is, unlike The Economist, as broad as it can possibly be. Right? We have every kind of content ranging from poems to essays to scientific papers to business presentations. So we want to create a smaller experience around these different content types so that it isn't just so broad, you can have a more narrow experience around your interests.

And then the third is building in more business models so that publishers can ultimately make more money. And we want to experiment with a lot of different models. Currently we have ads, premium accounts and commerce, but we want to try new commerce models. Like this subscription idea, like micro payments, like ads in books. And it's going to be an experimental and iterative process.

NICK: And for The Economist?

JOHN: I think in five years' time, you probably are going to see us experimenting more with things like bringing in more comments and things around the edge of apps. You'll probably get more info-graphics. You'll get some stuff.

I would probably, though, think it won't go that far. Because one of the great values, allegedly, at The Economist is, it's all the stuff we don't put in. We have to have that kind of finish-ability aspect which is what the iPad gives us but the web doesn't. And if you look at a website, if I look at The New York Times website, I could perhaps spend the rest of this year reading it, because there's a lot of enormously good stuff on it.

The advantage of a weekly magazine is you can sit there and think, I've read this thing. I've finished. And that is what we try to keep in the iPad. And I think that idea that people think, I'm trusting these people to tell me what's happened, and also to push out stuff I don't need, and they'll keep me informed. That sort of compact, I think, keeps the basic product somewhat similar.

But around the edge, yes, a lot of things could happen. And still particularly that bit of intelligent media, not in the sense that people need massive IQs to read it, but people are prepared to pay to get ideas as part of their diet. I'll talk about mass intelligence. That's where The New York Times comes from. That's where you come from. That's the bit we're all chasing. That's what people are all about here.

NICK: Cool. Well, that concludes everything. Thank you so much for coming. And I look forward to seeing you guys in five years, back here with flexible devices and the iPad 12. You can follow more of this coverage on scribd.com/documentedatdavos. Thank you.

Você também pode gostar

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Javascript Notes For ProfessionalsDocumento490 páginasJavascript Notes For ProfessionalsDragos Stefan NeaguAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- L GSR ChartsDocumento16 páginasL GSR ChartsEmerald GrAinda não há avaliações

- Arudha PDFDocumento17 páginasArudha PDFRakesh Singh100% (1)

- PDFDocumento653 páginasPDFconstantinAinda não há avaliações

- 5steps To Finding Your Workflow: by Nathan LozeronDocumento35 páginas5steps To Finding Your Workflow: by Nathan Lozeronrehabbed100% (2)

- DLP English 10 AIRADocumento8 páginasDLP English 10 AIRAMae Mallapre100% (1)

- Dog & Kitten: XshaperDocumento17 páginasDog & Kitten: XshaperAll PrintAinda não há avaliações

- A Project Report ON Strategic Purchasing Procedure, Systems and Policies (Hospital Industry)Documento20 páginasA Project Report ON Strategic Purchasing Procedure, Systems and Policies (Hospital Industry)amitwin1983Ainda não há avaliações

- Nancy Lublin Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento5 páginasNancy Lublin Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Beth Comstock Is Documented@DavosDocumento6 páginasBeth Comstock Is Documented@DavosDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Paulo Coelho Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento9 páginasPaulo Coelho Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by Scribd100% (1)

- David Drummond Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento8 páginasDavid Drummond Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Jonathan Miller Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento6 páginasJonathan Miller Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Nicholas Kristof Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento6 páginasNicholas Kristof Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Bill Tai of Charles River Ventures TranscriptDocumento4 páginasBill Tai of Charles River Ventures TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Lally Weymouth Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento6 páginasLally Weymouth Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Geoff Yang Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasGeoff Yang Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Keith Trent Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasKeith Trent Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Eric Goosby Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasEric Goosby Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Robert Moritz Is Documented@DavosDocumento5 páginasRobert Moritz Is Documented@DavosDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Niklas Zennstrom Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento7 páginasNiklas Zennstrom Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Rajiv Shah Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasRajiv Shah Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Keith Weed Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasKeith Weed Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Sarah Brown Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasSarah Brown Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Greg Lucier Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento5 páginasGreg Lucier Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Kathy Bloomgarden Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasKathy Bloomgarden Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Wendy Kopp Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento5 páginasWendy Kopp Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Guy Rolnick Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasGuy Rolnick Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Rep. Issa SOPA Panel TranscriptDocumento19 páginasRep. Issa SOPA Panel TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Jimmy Wales SOPA Panel TranscriptDocumento19 páginasJimmy Wales SOPA Panel TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Nouriel Roubini Is Documented@DavosDocumento7 páginasNouriel Roubini Is Documented@DavosDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Raja Rajamannar Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento5 páginasRaja Rajamannar Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Stefan Dyckerhoff Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumento4 páginasStefan Dyckerhoff Is Documented@Davos TranscriptDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- John Donahoe Is Documented@DavosDocumento6 páginasJohn Donahoe Is Documented@DavosDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Josette Sheeran Is Documented@DavosDocumento4 páginasJosette Sheeran Is Documented@DavosDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- Documented@Davos With Congressman Darrell IssaDocumento1 páginaDocumented@Davos With Congressman Darrell IssaDocumented at Davos 2011 - Presented by ScribdAinda não há avaliações

- .CLP Delta - DVP-ES2 - EX2 - SS2 - SA2 - SX2 - SE&TP-Program - O - EN - 20130222 EDITADODocumento782 páginas.CLP Delta - DVP-ES2 - EX2 - SS2 - SA2 - SX2 - SE&TP-Program - O - EN - 20130222 EDITADOMarcelo JesusAinda não há avaliações

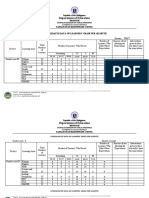

- Department of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterDocumento4 páginasDepartment of Education: Consolidated Data On Learners' Grade Per QuarterUsagi HamadaAinda não há avaliações

- CSWIP-WP-19-08 Review of Welding Procedures 2nd Edition February 2017Documento6 páginasCSWIP-WP-19-08 Review of Welding Procedures 2nd Edition February 2017oberai100% (1)

- WWW Ranker Com List Best-Isekai-Manga-Recommendations Ranker-AnimeDocumento8 páginasWWW Ranker Com List Best-Isekai-Manga-Recommendations Ranker-AnimeDestiny EasonAinda não há avaliações

- BECED S4 Motivational Techniques PDFDocumento11 páginasBECED S4 Motivational Techniques PDFAmeil OrindayAinda não há avaliações

- MATM1534 Main Exam 2022 PDFDocumento7 páginasMATM1534 Main Exam 2022 PDFGiftAinda não há avaliações

- Anker Soundcore Mini, Super-Portable Bluetooth SpeakerDocumento4 páginasAnker Soundcore Mini, Super-Portable Bluetooth SpeakerM.SaadAinda não há avaliações

- Internal Resistance To Corrosion in SHS - To Go On WebsiteDocumento48 páginasInternal Resistance To Corrosion in SHS - To Go On WebsitetheodorebayuAinda não há avaliações

- Swelab Alfa Plus User Manual V12Documento100 páginasSwelab Alfa Plus User Manual V12ERICKAinda não há avaliações

- D E S C R I P T I O N: Acknowledgement Receipt For EquipmentDocumento2 páginasD E S C R I P T I O N: Acknowledgement Receipt For EquipmentTindusNiobetoAinda não há avaliações

- ABS Service Data SheetDocumento32 páginasABS Service Data SheetMansur TruckingAinda não há avaliações

- Source:: APJMR-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Business-Establishments - PDF (Lpubatangas - Edu.ph)Documento2 páginasSource:: APJMR-Socio-Economic-Impact-of-Business-Establishments - PDF (Lpubatangas - Edu.ph)Ian EncarnacionAinda não há avaliações

- Fundasurv 215 Plate 1mDocumento3 páginasFundasurv 215 Plate 1mKeith AtencioAinda não há avaliações

- 4. Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, Sóc TrăngDocumento15 páginas4. Nguyễn Thị Minh Khai, Sóc TrăngK60 TRẦN MINH QUANGAinda não há avaliações

- Manhole Head LossesDocumento11 páginasManhole Head Lossesjoseph_mscAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 01 What Is Statistics?Documento18 páginasChapter 01 What Is Statistics?windyuriAinda não há avaliações

- Thesis TipsDocumento57 páginasThesis TipsJohn Roldan BuhayAinda não há avaliações

- TM Mic Opmaint EngDocumento186 páginasTM Mic Opmaint Engkisedi2001100% (2)

- Spanish Greeting Card Lesson PlanDocumento5 páginasSpanish Greeting Card Lesson Planrobert_gentil4528Ainda não há avaliações

- TTDM - JithinDocumento24 páginasTTDM - JithinAditya jainAinda não há avaliações

- Designed For Severe ServiceDocumento28 páginasDesigned For Severe ServiceAnthonyAinda não há avaliações

- Banking Ombudsman 58Documento4 páginasBanking Ombudsman 58Sahil GauravAinda não há avaliações