Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Oral Involvement in Primary Sjogren Syndrome

Enviado por

Jose Charris ADescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Oral Involvement in Primary Sjogren Syndrome

Enviado por

Jose Charris ADireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Oral involvement in primary Sjgren syndrome Philip C. Fox, Simon J. Bowman, Barbara Segal, Frederick B.

Vivino, Nandita Murukutla, Karen Choueiri, Sarika Ogale and Lachy McLean J Am Dent Assoc 2008;139;1592-1601 The following resources related to this article are available online at jada.ada.org ( this information is current as of July 25, 2011):

Updated information and services including high-resolution figures, can be found in the online version of this article at:

http://jada.ada.org/content/139/12/1592

This article cites 30 articles, 12 of which can be accessed free: http://jada.ada.org/content/139/12/1592/#BIBL Information about obtaining reprints of this article or about permission to reproduce this article in whole or in part can be found at: http://www.ada.org/990.aspx

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

2011 American Dental Association. The sponsor and its products are not endorsed by the ADA.

Oral involvement in primary Sjgren syndrome

Philip C. Fox, DDS, FDS RCSEd; Simon J. Bowman, PhD, FRCP; Barbara Segal, MD; Frederick B. Vivino, MD, FACR; Nandita Murukutla, PhD; Karen Choueiri, MA; Sarika Ogale, PhD; Lachy McLean, PhD, FRCP

rimary Sjgren syndrome (PSS) is a systemic autoimmune connectivetissue disorder characterized by inflammation of the exocrine glands that leads to secretory hypofunction and dryness of mucosal surfaces, most commonly of the eyes and mouth.1 The glands contain a characteristic focal mononuclear cell infiltrate with a loss of secretory parenchyma. A large majority of patients with PSS experience salivary gland dysfunction, which can lead to marked oral symptoms and compromised oral health.2 Systemic manifestations of PSS include autoantibodies directed against the anti-SS-A (Ro) antigens, the anti-SS-B (La) antigens or both in the majority of patients, as well as a number of other serologic manifestations. As many as one-quarter of patients with PSS experience other systemic features (termed extraglandular manifestations) of the condition, including inflammatory arthritis and neurological, cutaneous, hematologic or pulmonary involvement. Patients with PSS also have an approximately 20fold increase in the risk of developing B-cell lymphomas, most often of the exocrine glands.3,4 Sjgren syndrome (SS) is the second most common autoimmune rheumatic disorder, and the two forms combined (primary and secondary) have been estimated to

ABSTRACT

Background. In small studies, investigators have described oral features and their sequelae in primary Sjgren syndrome (PSS), but they have not provided a full picture of the aspects and implications of oral involvement. The authors describe what is, to their knowledge, the first large-scale evaluation to do so. In addition, they report data regarding utilization and cost of dental care among patients with PSS. Methods. The authors surveyed patients with primary Sjgren syndrome as identified by their physicians (PhysR-PSS), patient-members of the Sjgrens Syndrome Foundation (SSF-PSS) and control subjects who did not have PSS. They made comparisons between the three groups. Results. Subjects were 277 patients with PhysR-PSS, 1,225 patients with SSF-PSS and 606 control subjects. More than 96 percent of those in the patient groups experienced oral problems. An oral complaint was the initial symptom in more than one-half of the patients. Xerostomiaassociated signs and symptoms were common and severe, as evidenced by scores on an inventory of sicca symptoms. These patients rate of dental care utilization was high, and the care was costly. Conclusions. Oral and dental disease in PSS is extensive and persistent and represents a significant burden of illness. Clinical Implications. Oral symptoms and signs are common in patients with PSS. Early recognition of the significance of these findings by oral specialists could accelerate diagnosis and minimize oral morbidities. Key Words. Oral symptoms; primary Sjgren syndrome; quality of life; dental spending. JADA 2008;139(12):1592-1601.

Dr. Fox is the president, PC Fox Consulting, Via Monterione 29, 06038 Spello (PG), Italy, e-mail pcfox@comcast.net. Address reprint requests to Dr. Fox. Dr. Bowman is a consultant rheumatologist, University Hospital Birmingham (Selly Oak), Department of Rheumatology, Birmingham, England. Dr. Segal is an associate professor, Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis. Dr. Vivino is a clinical associate professor, Division of Rheumatology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Dr. Murukutla is a research manager, Health Care and Policy Research, Harris Interactive, New York City. Ms. Choueiri is a research associate, Health Care and Policy Research, Harris Interactive, New York City. Dr. Ogale is a health economist, Genentech, South San Francisco, Calif. Dr. McLean is a medical director, Genentech, South San Francisco, Calif.

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

1592

JADA, Vol. 139

http://jada.ada.org

December 2008

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

affect up to 1 percent of the population in the or were recommended to us by the Sjgrens SynUnited States.1 Women constitute approximately drome Foundation (SSF), Bethesda, Md. This 90 percent of patients with SS, with onset of process yielded a group with known, stringently symptoms and diagnosis typically occurring in diagnosed PSS. A large cross-sectional sample of middle age.1 patients with SS also was obtained through the The study we conducted and describe here is, SSF, which has a database of more than 8,500 to our knowledge, the first large-scale evaluation registered patients with SS. Finally, to create a of the oral health of patients with PSS in the healthy control comparison group, we asked United States. Indeed, it represents the largest patients from the SSF to provide surveys to survey of patients with PSS undertaken to date. friends of an age similar to those of the patients Investigators in numerous smaller clinical studies but without a diagnosis of PSS. All subjects, have described oral features and their sepatients and control subjects alike, came from quelae,5-13 but these studies have not provided a communities throughout the United States. comprehensive picture of the mulSUBJECTS, MATERIALS AND tiple aspects of oral involvement in METHODS This study is, PSS and the conditions effect on to our knowledge, quality of life and functioning in a Participants and procedures. large group of subjects. The pubWe recruited nine physicians at the first large-scale lished studies with the largest numevaluation of the oral rheumatology or oral medicine bers of subjects, which focused on clinics, whom either we or the SSF health of patients mortality among patients with PSS, identified as dealing with a high with primary Sjgren did not provide information on the volume of patients with SS, to parsyndrome in the specific oral manifestations of the ticipate in this study. We asked the United States. disorder.14-16 Some European invesnine physicians to identify from tigators provided valuable informatheir records all patients classified tion on the spectrum of the disorder as having PSS according to the but did not focus on oral aspects.17,18 2002 AECG criteria.19 We asked In our study, we obtained detailed information physicians who had 100 or fewer patients with on PSS to recruit all eligible patients for the survey. dthe path patients followed to diagnosis; We asked physicians who had more than 100 elidthe range, frequency, severity and impact of a gible patients to select 100 patients at random comprehensive spectrum of oral symptoms and and recruit them for the study. In total, staff signs experienced; members in the nine offices mailed surveys to 547 dthe patients utilization of ongoing dental care patients, a sample we refer to as having physiand the burdens associated with that care; cian-referred PSS (PhysR-PSS). In addition, SSF dthe treatments (both conventional and alternastaff members mailed surveys to 8,694 active tive) that patients underwent; patient-members of the SSF (a sample hereafter dthe effects of illness on patients general referred to as SSF-PSS). We asked, via the quality of life. questionnaire instructions, one-half of these SSF We used self-reported data collected by means patients to give a survey to a friend of the same of a mailed survey. To minimize the inherent age and sex as the patient but who did not have a weaknesses of such a design, we recruited subjects to the study through multiple sources with ABBREVIATION KEY. AECG: American-European the aim of creating a population representative of Consensus Group. PhysR-PSS: Physician-referred people with PSS. We recruited patients with a patientprimary Sjgren syndrome. PROFAD-SSI: physician-confirmed diagnosis of primary SS Profile of Fatigue and DiscomfortSicca Symptoms according to criteria published by the 2002 Inventory. PSS: Primary Sjgren syndrome. SF-36: American-European Consensus Group Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health (AECG)19through nine rheumatology and oral Survey. SS: Sjgren syndrome. SS-A (Ro): Sjgren synmedicine practices that have a high volume of drome antibody-A. SS-B (La): Sjgren syndrome patients with SS and expertise in treating this antibody-B. SSF: Sjgrens Syndrome Foundation. condition. These practices either were known to SSF-PSS: Sjgrens Syndrome Foundationprimary Sjgren syndrome. us as having a high volume of patients with PSS

JADA, Vol. 139 http://jada.ada.org December 2008 1593

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

diagnosis of SS; this group would become a demomine differences between the three groups in the graphically matched comparison group (control occurrence of events. Likewise, we performed sepsubjects). arate 2 tests comparing two groups at a time if The study was approved by the Western Instiwe noted any significant (P .05) overall 2 comtutional Review Board, Olympia, Wash., and, as parison of the three groups. Finally, to determine needed, by the local institutional review boards the relationship between oral sicca symptoms and with which the recruiting physicians were assoquality of life, we conducted Pearson product ciated. The respondent-completed, paper-based moment correlation tests between the oral sicca questionnaire was unintrusive and completely domain of the PROFAD-SSI and the eight anonymous. Additionally, the researchers did not quality-of-life domains of the SF-36. have direct access to the sample, as third parties RESULTS (staff members of physicians offices and the SSF) mailed the surveys to patients. Therefore, the Of 547 surveys sent through participating physiinstitutional review boards deemed the survey cians offices, respondents returned 281 (51 perappropriate for use with human subjects and did cent). Of these, four were duplicates, and we not require an informed consent form for approval excluded them. Of the 8,694 surveys sent to SSF by the Western Institutional Repatients, 3,939 (45 percent) were view Board or other university returned. Control subjects returned Dry mouth lasting boards from which approval was 630 surveys. longer than three obtained. We collected data between Sample eligibility. All particiJan. 1 and July 31, 2007. pating physician sites confirmed months was one of Survey items. Participants comthe identification and recruitment the sicca symptoms pleted the self-administered Assessof patients with a diagnosis of PSS reported most often. ment of Symptoms and Experiences according to the 2002 AECG classiof Sjgrens Syndrome survey that fication criteria.19 Therefore, we we developed for this project. It included quesconsidered all 277 patients with PSS to be eligible tions about medical and dental history and the for the study. Of the 3,939 SSF patients who following prevalidated instruments: the Profile of returned surveys, we classified 1,225 (31.1 perFatigue and DiscomfortSicca Symptoms Invencent) as being likely to have PSS on the basis of tory (PROFAD-SSI),20,21 Medical Outcomes Study patients reported positive labial minor salivary 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36),22 the gland biopsy results, anti-SS-A (Ro) or SS-B (La) Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness antibody test results or both, and lack of concurTherapy Fatigue scale,23 the Center of Epidemiorent diagnoses of other rheumatic conditions logic Studies Depression Scale,24 the Thinking (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erytheScale25 and the modified Brief Pain Inventory matosus, mixed connective-tissue disease, short form.26 In this article, we report data myositis or scleroderma). We confirmed 60 perregarding the oral aspects of PSS, as well as cent of the 547 patients with PhysR-PSS as selected information from the PROFAD-SSI and having positive test results for anti-SS-A (Ro) SF-36 results. Other data from the survey will be antibodies, anti-SS-B (La) antibodies or both, as presented separately (B. Segal and colleagues, determined by the recruiting physicians, and 65 unpublished data, July 2007). (The survey instrupercent of the SSF-PSS group reported having ment is available as supplemental data to the anti-SS-A (Ro) antibodies, anti-SS-B (La) antionline version of this article [found at bodies or both. These demographics are generally http://jada.ada.org].) similar to expected frequencies of these autoantiData analysis. We scored all of the prevalibodies in patients with this disorder and to results of previous reports regarding cohorts of dated instruments according to their original patients with PSS.1,13,27-31 scoring algorithms. We computed univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAs) for all mean score Finally, among the 630 surveys received from comparisons between the PhysR-PSS, SSF-PSS peer control subjects, we excluded from further and control groups. We followed up significant analyses surveys from 24 subjects who reported ANOVAs with Fisher least significant difference having received a diagnosis of SS or another tests to determine which specific groups differed rheumatic condition. Thus, we based our analyses from one another. We computed 2 tests to deteron data from 606 control subjects, 277 patients

1594 JADA, Vol. 139 http://jada.ada.org December 2008

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

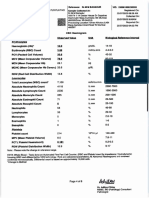

TABLE 1 with PhysR-PSS and 1,225 SSF-PSS patients. A comparison of patients demographic data Demographics. Patients with and characteristics between study groups.* PhysR-PSS, SSF-PSS patients and control subjects were largely similar in DEMOGRAPHICS AND STUDY GROUP CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS terms of demographics (Table 1), and PhysR-PSS SSF-PSS Control (n = 277) (n = 1,225) (n = 606) the profile of patients is consistent with Age, in Years (Mean SD) 62 12.6 61 12.7 61 12.2 that reported in prior large case 13,15-18 Sex (% Female) 90 93 92 series. Patients with PhysR-PSS were, on average, 62 years old; SSFWeight, in Pounds 155 39.3 151 34.6 159 35.1 (Mean SD) PSS patients and control subjects were, Height, in Inches 64 3.6 65 3.4 65 5.9 on average, 61 years old (P > .05). At (Mean SD) least 90 percent of the members of each Ethnicity (%) group were women. However, patients White 89 94 96 in both the PhysR-PSS and SSF-PSS Other 8# 4 3 groups were significantly less likely to Employed (%) 38 41 49 be currently employed than were conGeographic Distribution (%) trol subjects (patients with PhysR-PSS, East 45# 27 25 South 27 30 29 38 percent; SSF-PSS patients, 41 perMidwest 22 21 24 cent; control subjects, 49 percent; West 4 21 20 P < .05). * Differences between groups in mean values were tested with univariate analyses of Path to diagnosis. Patients with variance and follow-up t tests. Differences in percentages were tested with tests. PhysR-PSS and SSF-PSS patients PhysR-PSS: Physician-referredprimary Sjgren syndrome. SSF-PSS: Sjgrens Syndrome Foundationprimary Sjgren syndrome. reported similar experiences in their Significantly (P < .05) higher than patients with PhysR-PSS. path to a diagnosis of PSS (Table 2). Significantly (P < .05) higher than for SSF-PSS patients. # Significantly (P < .05) higher than for control patients. The mean time since diagnosis was 9.0 years for patients with PhysR-PSS and 10.1 years for SSF-PSS patients (P > .05). The more frequently than did SSF-PSS patients. Salimean time between the first experience of SS-like vary scans had been used less commonly than symptoms and a confirmed diagnosis was seven salivary flow tests and biopsy in diagnosis for years in both patient groups. More than one-third both the PhysR-PSS and SSF-PSS groups. of patients reported dry mouth as the initial Clinical characteristics. Oral problems were symptom, making it one of the most frequent highly prevalent among patients with PSS; we early manifestations of PSS. In addition, 17 pernoted few, relatively minor differences between cent of patients with PhysR-PSS and 12 percent the patients with PhysR-PSS and SSF-PSS of SSF-PSS patients reported having problems patients (Table 3, page 1597). Dry mouth lasting with teeth or gingivae, and 18 percent of patients longer than three months was one of the sicca with PhysR-PSS and 15 percent of SSF-PSS symptoms reported most often, and dental caries patients reported swollen salivary glands as iniand parotid gland swelling were the most fretial complaints. Overall, more than one-half of quently reported oral signs in both patient patients with PhysR-PSS and SSF-PSS patients groups. Oral ulceration and fungal (yeast) infecreported experiencing an oral symptom as the tions also were common. Patients also reported first manifestation of PSS. However, only 8 pergreater fatigue and sicca severity on the cent of patients with PhysR-PSS and 6 percent of PROFAD-SSI than did control subjects. We also SSF-PSS patients received a PSS diagnosis from noted lower functioning in all domains of the SFa dentist (P > .05). Rheumatologists were by far 36 for both patient groups (data not shown; full the most likely to diagnose PSS: more than oneSF-36 data will be reported in a future publicahalf of the patients in both groups reported tion [B. Segal and colleagues, unpublished data, having received a PSS diagnosis from a rheumaJuly 2007]). All oral and ocular manifestations tologist. More than one-half of the patients had about which subjects were asked were signifiundergone lip biopsies as part of the PSS diagcantly more common in patients than in control nostic evaluation. Patients with PhysR-PSS subjects. reported having undergone salivary flow tests Relationship between oral sicca

2

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

JADA, Vol. 139

http://jada.ada.org

December 2008

1595

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

TABLE 2

Path to diagnosis among patients with primary Sjgren syndrome.

PATH TO DIAGNOSIS STUDY GROUP PhysR-PSS * (n = 277) Mode of Presentation (Initial Complaint) (%) Dry eyes Dry mouth Fatigue Muscle pain Tooth/gum problems Swollen salivary glands Dry mouth OR tooth/gum problems OR swollen salivary glands Diagnosing Physician (%) Rheumatologist Primary care physician Dentist Ophthalmologist Use of Salivary Tests in Diagnosis (% of Patients) Lip biopsy Salivary scan Salivary flow (spit test) Time From First Symptom to Diagnosis (Mean SD Years) Disease Duration: Time From Initial Symptoms to Present (Mean SD Years) * PhysR-PSS: Physician-referred patientprimary Sjgren syndrome. SSF-PSS: Sjgrens Syndrome Foundationprimary Sjgren syndrome. Significantly (P < .05) higher than for SSF-PSS patients. Significantly (P < .05) higher than for patients with PhysR-PSS. 53 25 51 7.1 9.4 9.0 8.4 51 12 23 7.0 8.7 10.1 8.2 62 10 8 7 57 17 6 6 44 39 27 21 17 18 54 41 34 23 12 12 15 50 SSF-PSS (n = 1,225)

Although patients and control subjects were equally as likely to have ever visited a dentist, patients were significantly more likely to have seen an oral surgeon in their lifetimes than were control subjects. Furthermore, in comparison with control subjects, patients with PSS reported having had a significantly greater number of dental visits, more decayed teeth and more dental restorations in the preceding year. Of particular note is our finding that annual out-of-pocket dental care spending was, on average, two to three times higher among patients than among control subjects.

DISCUSSION

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

symptoms and quality of life. As indicated in Table 4 (page 1598) oral sicca symptoms, as measured with the PROFAD-SSI, were associated significantly with reduced quality of life in all domains of the SF-36 for patients with PhysRPSS and SSF-PSS patients. In particular, greater sicca severity was associated with reduced general health, social functioning and lower energy levels and greater fatigue levels in both patient groups. Dental care utilization. Dental care utilization was significantly greater among patients with PSS than among control subjects (Table 5, page 1599). Again, the results were similar for both patient groups. Most patients required some treatment for their oral complaints, and more than one-half used a prescription secretagogue for dry-mouth symptoms. Patients also were significantly more likely than were control subjects to ever have used or to be using alternative and nontraditional remedies, such as acupuncture, omega-3 fatty acids or fish oil or a restricted diet.

1596 JADA, Vol. 139 http://jada.ada.org December 2008

To our knowledge, our data represent the largest survey results and the most comprehensive picture of oral involvement available for patients with PSS. Authors of previously published case series have provided valuable knowledge of the natural history and manifestations of PSS but have not reported detailed information on the disorders oral aspects.13-18 For example, Pertovaara and colleagues13 reported about complaints of xerostomia (77 percent) and parotid swelling (32 percent) in 87 patients, and Ioannidis and colleagues,15 in a retrospective study of 723 patients, reported only oral symptoms in 96 percent of patients and parotid enlargement in 44 percent of patients. Theander and colleagues,16 in a prospective cohort study of 484 patients, provided data regarding oral involvement only on salivary gland enlargement, which was found in 20 percent of the population overall. Direct comparisons of those results with the results of our study are difficult to make, owing to differences in diagnostic criteria used and manifestations queried, but there is general agreement as to the prevalence and significance of oral involvement in PSS.

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

TABLE 3 We obtained data from 277 subjects who had a Effects of Sjgren syndrome according to study group. diagnosis from their physicians of PSS on the basis of EFFECT STUDY GROUP the AECG criteria. These PhysR-PSS * SSF-PSS Control are the most widely (n = 277) (n = 1,225) (n = 606) accepted classification criSicca Symptoms (% Ever Experienced) teria and are considered a Dry mouth lasting for more than three months 88 91 4 stringent means of diagNeed liquids to swallow food 72 78 6 Trouble swallowing 60 67 7 nosis for clinical studies. Trouble speaking 50 56 4 Additionally, we classified Choking 40 42 10 1,225 patient-members of 44 44 9 the SSF who completed the Oral pain Dry eyes for more than three months 88 92 12 survey as having PSS on Sensation of sand or gravel in the eye 73 83 20 the basis of self-reported Photosensitivity (sunlight) 70 72 18 criteria that corresponded Oral Signs (% Ever Experienced) to those used in the AECG. Severe gum disease 21 18 6 Although we did not conDental caries 55 56 22 firm the diagnosis of the Tooth loss 37 32 19 members of the survey Mouth ulcers 41 46 12 group by examining their Salivary gland stones or infections 17 20 3 medical records, we believe Fungal infection in mouth 31 35 4 that the marked similarity Parotid gland swelling 43 48 2 in responses between the (Mean SD) # PROFAD-SSI physician-diagnosed cohort PROFAD score 10.1 6.6 10.4 6.1 3.6 4.0 and the SSF member SSI score 11.7 6.5 12.6 6.0 3.0 3.2 cohort argues that the * PhysR-PSS: Physician-referred patientprimary Sjgren syndrome. SSF-PSS group represents SSF-PSS: Sjgrens Syndrome Foundationprimary Sjgren syndrome. Significantly (P < .05) higher than for control subjects. a true population with Significantly (P < .05) higher than for patients with PhysR-PSS. PSS and one comparable PROFAD-SSI: Profile of Fatigue and DiscomfortSicca Symptoms Inventory (Bowman and colleagues20; Bowman and colleagues21). with the PhysR-PSS popu# Higher scores indicate poorer functioning. lation. We have reported the data separately for the groups, but they did not differ in terms of any survey studies, and the clinical and demographic clinically significant variables. One always must data generally were as expected for a population view data collected via survey methods and with PSS. Furthermore, the data are similar patients self-reports with caution; however, as between the larger SSF-PSS group and the more noted above, we did not find marked differences selective PhysR-PSS group. This finding provided in the two patient groups, either demographically us with some confidence that the responding subor clinically, compared with information from jects were a fair representation of people with published case series or prospective or retrospecPSS in the United States. tive studies. In particular, age, sex, prevalence of The use of a subject-recruited healthy control oral complaints and laboratory findings in our group ensured that this cohort was well-matched study all were similar to previously reported with the patient groups in terms of demographic findings. (and geographic) variables. Although we excluded We recognize that patients who respond to surpotential control subjects who reported having a veys may differ from those who choose not to parrheumatic disorder, we included control subjects ticipate. We have no information on any differwith any other medical condition and did not conences that may exist between the respondents trol for other potential comorbidities. In other and the nonresponders in this study. However, words, we made no attempt to recruit a superthe response rates (uncorrected rate for patients healthy group of control subjects. The control with PhysR-PSS, 51 percent; uncorrected rate for subjects had a low prevalence of dry mouth, as SSF-PSS patients, 45 percent) were high for mailwas the case in other published studies (a range

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

JADA, Vol. 139

http://jada.ada.org

December 2008

1597

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

TABLE 4

tial diagnosis for these complaints and could lead to earlier diagnosis. Association between oral sicca severity The need for health professionals to (PROFAD-SSI*) and quality of life (SF-36 ) improve their recognition of SS is in affected subjects. demonstrated clearly by the length of time required to obtain a diagnosis SUBJECT GROUP QUALITY-OF-LIFE DOMAINS R (P < .01) (SF-36 DOMAINS) (Table 2). On average, at least seven years elapsed between the patients iniPhysR-PSS Physical functioning 0.29 0.25 Role limitations due to physical health tial experience of symptoms or signs and 0.17 Role limitations due to emotional problems the establishment of a definitive diag0.35 Energy or fatigue 0.23 Emotional well-being nosis. Greater awareness of PSS among 0.30 Social functioning oral health care practitioners could 0.35 Pain 0.43 General health reduce this delay in diagnosis. As noted SSF-PSS Physical functioning 0.30 above, oral signs and symptoms often Role limitations due to physical health 0.26 are the initial manifestation of PSS. 0.25 Role limitations due to emotional problems 0.28 Energy or fatigue Furthermore, patients saw their dentists 0.20 Emotional well-being more frequently than did control sub0.32 Social functioning 0.27 Pain jects (Table 5). Therefore, dentists have 0.30 General health a unique opportunity to start the diag* PROFAD-SSI: Profile of Fatigue and DiscomfortSicca Symptoms Inventory nostic process. The fact that clinicians (Bowman and colleagues ; Bowman and colleagues ). commonly use oral tests (questions SF-36: Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (Ware and colleagues ). about xerostomia, salivary flow test, lip PhysR-PSS: Physician-referred patientprimary Sjgren syndrome. biopsy) (Table 2) in diagnosing PSS SSF-PSS: Sjgrens Syndrome Foundationprimary Sjgren syndrome. emphasizes the important role that dental professionals couldand shouldplay in of prevalence of dry mouth in the general populadiagnosis of this condition. It is possible that the tion between 10 and 29 percent32,33). However, the low percentage of dentists responsible for a diagresponses and subsequent prevalence rates for nosis reported in Table 2 is an underestimation. xerostomia depend highly on how the question is Subjects were asked which health care provider asked and how the definition of dry mouth is made the diagnosis, not which health care provider applied. By using the AECG format, according to suggested the subject might have PSS. Primary which we defined xerostomia as dry mouth care practitioners may refer patients to specialists lasting for more than three months, we believe (rheumatologists or oral medicine specialists) to we used a more stringent criterion than was used make the final diagnosis. in many other studies. This factor may be an The results presented in Table 3 show the explanation for the relatively low prevalence of effect of PSS on the oral cavity and oral functions. xerostomia found among the control subjects. Virtually all patients with PSS experience oral The results present a compelling argument for symptoms, with about 90 percent reporting perthe importance of dental health professionals sistent xerostomia. The majority of patients with increasing their understanding of SS. Dry mouth PSS also had difficulties with eating, swallowing, was the initial symptom experienced by more speaking and caries. The pervasive effects of xerothan one-third of the patients in our study (Table stomia on oral comfort and functions are well2). This was the second most common initial comrecognized,31 and for most patients with PSS plaint, close in frequency to the most commonly cited symptom of dry eyes. In addition to xerothese are persistent and significant. That is borne stomia, a substantial number of patients with out by the results of the PROFAD-SSI. The signifPSS reported tooth or gingival problems or icant association of the PROFAD-SSI with all swollen salivary glands as initial complaints. In domains of the SF-36 (Table 4) demonstrates that total, more than one-half of the patients experithe effect of PSS is widespread and severe. In this enced an oral symptom or sign as the first manilight, the significantly lower employment rate festation of the disorder. Increased recognition among patients with PSS (Table 1) was an interamong practitioners that the oral cavity, head esting finding and may be a reflection of the and neck are the primary sites of early symptoms burden that the illness places on them. of SS could lead to inclusion of SS in the differenRecently, Stewart and colleagues5 reported

20 21 22

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

1598

JADA, Vol. 139

http://jada.ada.org

December 2008

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

TABLE 5

Therapies and dental care utilization among study groups.

DENTAL CARE UTILIZATION PhysR-PSS * (n = 277) Providers Ever Seen (%) Dentist Oral medicine specialist or oral surgeon Oral Treatments Ever Used (%) Saliva substitutes (artificial saliva) Oral comfort agents (gels, rinses, sprays) Fluoride Cevimeline or pilocarpine Oral Treatments Currently Used (%) Saliva substitutes (artificial saliva) Oral comfort agents (gels, rinses, sprays) Fluoride Cevimeline or pilocarpine Alternative/Complementary Therapies Ever Used (%) Acupuncture Yoga, tai chi, meditation Health food remedies Omega-3 fatty acids or fish oil Restricted diet Alternative/Nontraditional Therapies Currently Used (%) Acupuncture Yoga, tai chi, meditation Health food remedies Omega-3 fatty acids or fish oil Restricted diet Visits to Dentist in Past 12 Months (Mean SD) Decayed Teeth or Dental Restorations in Past 12 Months (Mean SD) Out-of-Pocket Spending on Dental Care in Past 12 Months (Median SD $) * PhysR-PSS: Physician-referred patientprimary Sjgren syndrome. SSF-PSS: Sjgrens Syndrome Foundationprimary Sjgren syndrome. Significantly (P < .05) higher than for control subjects. Significantly (P < .05) higher than for patients with PhysR-PSS. Significantly (P < .05) higher than for SSF-PSS patients. 96 49 56 61 53 57 34 45 40 44 22 30 64 56 29 6 16 54 44 16 4.0 3.7 2.6 3.6 1,473.3 2,948.9 STUDY GROUP SSF-PSS (n = 1,225) 97 43 60 68 63 57 33 53 45 37 23 29 69 61 25 6 16 59 48 21 3.8 3.3 2.2 3.0 1,335.2 3,445.4 Control (n = 606) 96 31 1 12 23 1 0.5 4 9 0.3 11 23 64 34 18 2 12 54 26 10 2.3 1.9 0.8 1.4 503.6 1,274.4

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

about quality of life in a group of 39 patients with SS and the conditions effect on their general health. The investigators found pervasive effects of these patients oral involvement, and they concluded that SS had major effects on systemic health and quality of life. Results from our study greatly expand on and reinforce these findings, because we examined a broader range of signs and symptoms in a larger patient group. PSS symptoms are of sufficient severity that the majority of patients seek treatment for their oral condition. As shown in Table 5, almost onehalf of patients with PSS reported using, at the time they completed the survey, oral comfort

agents or supplemental fluoride. The availability of agents to reduce dry-mouth symptoms by increasing salivary output has had an effect on PSS treatment. More than one-half of patients had tried a prescription parasympathomimetic secretagogue, and more than one-third reported that they used this therapeutic option at the time they completed the survey. There also was widespread use of alternative and complementary therapies, suggesting that allopathic options are not adequate for many patients. Such widespread use also points out the importance, when taking a medication history, of asking patients specifically about their use of any alternative or

JADA, Vol. 139 http://jada.ada.org December 2008 1599

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

complementary therapies. A further measure of the effect of PSS is the data regarding dental care utilization in Table 5. Dental care for patients with PSS is sought frequently and is expensive. To attempt to maintain oral health and comfort, patients saw their dentists about twice as often as did control subjects. In comparison with control subjects, they had experienced about three times the amount of dental disease in the preceding year and expended about three times as much for their care. This is a continuing problem and burden. To our knowledge, these data are the first to document the economic impact of PSS, which is manifested through increased oral health care costs and reduced employment. A surprisingly low percentage of both the patients and the control subjects reported ever having experienced tooth loss or dental caries. Subjects may have responded to these questions on the basis of their experiences in the previous year, about which the survey also inquired, and not of their lifetime experience. We do not have a clear explanation for these data but note that they are consistent internally between groups.

CONCLUSION

the dental office are critical.

Disclosure. The medical authors of this articleDrs. Fox, Bowman, Segal and Vivinoreceived consultancy payments from Genentech, South San Francisco, Calif., for their time spent on questionnaire and project design, project implementation and data analysis in preparation for publication. The study described in this article was funded by Genentech, South San Francisco, Calif. Data collection and analysis were performed by Harris Interactive, New York City. The authors thank the Sjgrens Syndrome Foundation, Bethesda, Md., for its enthusiastic support. In particular, they thank Steven Taylor, chief executive officer, and the foundation members who took part in this survey. The authors also thank the rheumatologists and oral medicine specialistsDrs. Steven Carsons, Stuart Kassan, Athena Papas, Nelson Rhodus, Daniel Small, Harry Spiera and Neil Stahl who aided them, as well as these doctors patients who participated in this project. 1. Kassan SS, Moutsopoulos HM. Clinical manifestations and early diagnosis of Sjgren syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2004;164(12): 1275-1284. 2. Mathews SA, Kurien BT, Scofield RH. Oral manifestations of Sjgrens syndrome. J Dent Res 2008;87(4):308-318. 3. Dawson LJ, Fox PC, Smith PM. Sjogrens syndrome: the nonapoptotic model of glandular hypofunction. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45(7):792-798. 4. Zintzaras E, Voulgarelis M, Moutsopoulos HM. The risk of lymphoma development in autoimmune diseases: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(20):2337-2344. 5. Stewart CM, Berg KM, Cha S, Reeves WH. Salivary dysfunction and quality of life in Sjgren syndrome: a critical oral-systemic connection. JADA 2008;139(3):291-299. 6. Roberts C, Parker GJ, Rose CJ, et al. Glandular function in Sjgren syndrome: assessment with dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and tracer kinetic modelinginitial experience. Radiology 2008;246(3):845-853. 7. Leung KC, Leung WK, McMillan AS. Supra-gingival microbiota in Sjgrens syndrome. Clin Oral Investig 2007;11(4):415-423. 8. van den Berg I, Pijpe J, Vissink A. Salivary gland parameters and clinical data related to the underlying disorder in patients with persisting xerostomia. Eur J Oral Sci 2007;115(2):97-102. 9. Leonard G, Flint S. Oral and dental aspects of Sjgrens syndrome. J Ir Dent Assoc 2006;52(3):130-136. 10. Mrton K, Boros I, Varga G, et al. Evaluation of palatal saliva flow rate and oral manifestations in patients with Sjgrens syndrome. Oral Dis 2006;12(5):480-486. 11. Pijpe J, Kalk WW, Bootsma H, Spijkervet FK, Kallenberg CG, Vissink A. Progression of salivary gland dysfunction in patients with Sjogrens syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66(1):107-112. 12. Helenius LM, Meurman JH, Helenius I, et al. Oral and salivary parameters in patients with rheumatic diseases. Acta Odontol Scand 2005;63(5):284-293. 13. Pertovaara M, Korpela M, Uusitalo H, et al. Clinical follow up study of 87 patients with sicca symptoms (dryness of eyes or mouth, or both). Ann Rheum Dis 1999;58(7):423-427. 14. Skopouli FN, Dafni U, Ioannidis JP, Moutsopoulos HM. Clinical evolution, and morbidity and mortality of primary Sjgrens syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2000;29(5):296-304. 15. Ioannidis JP, Vassiliou VA, Moutsopoulos HM. Long-term risk of mortality and lymphoproliferative disease and predictive classification of primary Sjgrens syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46(3):741-747. 16. Theander E, Manthorpe R, Jacobsson LT. Mortality and causes of death in primary Sjgrens syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50(4):1262-1269. 17. Garca-Carrasco M, Ramos-Casals M, Rosas J, et al. Primary Sjgren syndrome: clinical and immunologic disease patterns in a cohort of 400 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81(4):270-280. 18. Champey J, Corruble E, Gottenberg JE, et al. Quality of life and psychological status in patients with primary Sjgrens syndrome and sicca symptoms without autoimmune features. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 55(3):451-457. 19. Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, et al. Classification criteria for Sjgrens syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61(6):554-558. 20. Bowman SJ, Booth DA, Platts RG; UK Sjgrens Interest Group.

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

Investigators have published numerous reports of various oral aspects of SS.5-12 However, most have examined relatively small groups or focused on a particular aspect of the condition. We believe our report is the first to evaluate a large number of subjects (> 1,000) and the first to attempt to capture the full spectrum of the conditions oral signs and symptoms, as well as its effect on patients general health and well-being. Our results clearly demonstrate the marked effects of PSS and also present a clear challenge to oral health care professionals. The results suggest that dentists often see patients with PSS early in their disease course; indeed, they may be the first health care practitioners from whom a patient with PSS seeks care. Dentists have an opportunity to recognize the possibility of SS early and facilitate a more rapid diagnosis of the condition. Along with earlier diagnosis comes the possibility of earlier intervention. With careful management and use of appropriate preventive measures, many of the negative health consequences of PSS can be minimized or eliminated. This, in turn, could reduce the economic and general health burdens seen in patients with this condition. Greater awareness and recognition of SS in

1600 JADA, Vol. 139 http://jada.ada.org December 2008

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

Measurement of fatigue and discomfort in primary Sjgrens syndrome using a new questionnaire tool. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(6): 758-764. 21. Bowman SJ, Booth DA, Platts RG, Field A, Rostron J; UK Sjgrens Interest Group. Validation of the Sicca Symptoms Inventory for clinical studies of Sjgrens syndrome. J Rheumatol 2003;30(6): 1259-1266. 22. Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Centre; 1993. 23. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;13(2):63-74. 24. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychological Meas 1977;1: 385-401. 25. Shikiar R, Howard K, Yu EB, et al. Validation of LUP-QOL: a lupus-specific measure of health-related quality of life. Poster presented at: European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) 2006 Annual Congress; June 2006; Amsterdam, Netherlands. 26. Salek S. Compendium of Quality of Life Instruments. Vol. 2.; New York City: Wiley; 1998.

27. Gob V, Salle V, Duhaut P, et al. Clinical significance of autoantibodies recognizing Sjgrens syndrome A (SSA), SSB, calpastatin and alpha-fodrin in primary Sjgrens syndrome. Clin Exp Immunol 2007; 148(2):281-287. 28. Locht H, Pelck R, Manthorpe R. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of measuring antibodies to alpha-fodrin compared to anti-Ro-52, anti-Ro-60, and anti-La in primary Sjgrens syndrome. J Rheumatol 2008;35(5):845-849. 29. Cai FZ, Lester S, Lu T, et al. Mild autonomic dysfunction in primary Sjgrens syndrome: a controlled study. Arthritis Res Ther 2008; 10(2):R31. 30. Routsias JG, Tzioufas AG. Sjgrens syndrome: study of autoantigens and autoantibodies. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2007;32(3): 238-251. 31. Fox PC, van der Ven PF, Sonies BC, Weiffenbach JM, Baum BJ. Xerostomia: evaluation of a symptom with increasing significance. JADA 1985;110(4):519-525. 32. Hochberg MC, Tielsch J, Munoz B, Bandeen-Roche K, West SK, Schein OD. Prevalence of symptoms of dry mouth and their relationship to saliva production in community dwelling elderly: the SEE project. Salisbury Eye Evaluation. J Rheumatol 1998;25(3):486-491. 33. Guggenheimer J, Moore PA. Xerostomia: etiology, recognition and treatment. JADA 2003;134(1):61-69.

Downloaded from jada.ada.org on July 25, 2011

JADA, Vol. 139

http://jada.ada.org

December 2008

1601

Copyright 2008 American Dental Association. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission.

Você também pode gostar

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Adobe Scan Jul 28, 2023Documento6 páginasAdobe Scan Jul 28, 2023Krishna ChaurasiyaAinda não há avaliações

- Nursing Management of HypertensionDocumento152 páginasNursing Management of HypertensionEnfermeriaAncam100% (3)

- A Sonographic Sign of Moderate ToDocumento5 páginasA Sonographic Sign of Moderate ToDivisi FER MalangAinda não há avaliações

- ScenarioDocumento1 páginaScenarioAngel Lynn YlayaAinda não há avaliações

- HEX PG SyllabusDocumento124 páginasHEX PG SyllabusJegadeesan MuniandiAinda não há avaliações

- Liver Meeting Brochure 2016 PDFDocumento4 páginasLiver Meeting Brochure 2016 PDFManas GhoshAinda não há avaliações

- A Manual 20199 CompleetDocumento201 páginasA Manual 20199 CompleetJanPerezAinda não há avaliações

- 3yc CrVlEemddAqBQMk Og 1.4 Six Artifacts From The Future of Food IFTF Coursera 2019Documento13 páginas3yc CrVlEemddAqBQMk Og 1.4 Six Artifacts From The Future of Food IFTF Coursera 2019Omar YussryAinda não há avaliações

- Histopathology of Dental CariesDocumento7 páginasHistopathology of Dental CariesJOHN HAROLD CABRADILLAAinda não há avaliações

- Upper Gastrointestinal BleedingDocumento41 páginasUpper Gastrointestinal BleedingAnusha VergheseAinda não há avaliações

- Actisorb Silver 220: Product ProfileDocumento12 páginasActisorb Silver 220: Product ProfileBeaulah HunidzariraAinda não há avaliações

- 11 Retention of Maxillofacial Prosthesis Fayad PDFDocumento7 páginas11 Retention of Maxillofacial Prosthesis Fayad PDFMostafa Fayad50% (2)

- Cast and SplintsDocumento58 páginasCast and SplintsSulabh Shrestha100% (2)

- Cytogenetics - Prelim TransesDocumento15 páginasCytogenetics - Prelim TransesLOUISSE ANNE MONIQUE L. CAYLOAinda não há avaliações

- 10a General Pest Control Study GuideDocumento128 páginas10a General Pest Control Study GuideRomeo Baoson100% (1)

- Cardiology - Corrected AhmedDocumento23 páginasCardiology - Corrected AhmedHanadi UmhanayAinda não há avaliações

- ESC - 2021 - The Growing Role of Genetics in The Understanding of Cardiovascular Diseases - Towards Personalized MedicineDocumento5 páginasESC - 2021 - The Growing Role of Genetics in The Understanding of Cardiovascular Diseases - Towards Personalized MedicineDini SuhardiniAinda não há avaliações

- Nightinale Paper 400 WordsDocumento4 páginasNightinale Paper 400 WordsAshni KandhaiAinda não há avaliações

- Polydactyly of The Foot A Review.92Documento10 páginasPolydactyly of The Foot A Review.92mamyeu1801Ainda não há avaliações

- Principles - of - Genetics 6th Ed by Snustad - 20 (PDF - Io) (PDF - Io) - 12-14-1-2Documento2 páginasPrinciples - of - Genetics 6th Ed by Snustad - 20 (PDF - Io) (PDF - Io) - 12-14-1-2Ayu JumainAinda não há avaliações

- Farming Hirudo LeechesDocumento46 páginasFarming Hirudo LeechesCatalin Cornel100% (1)

- Lecture 1. Advanced Biochemistry. Introduction.Documento70 páginasLecture 1. Advanced Biochemistry. Introduction.Cik Syin100% (1)

- ENGLISH 6 - Q4 - Wk7 - USLeM RTPDocumento11 páginasENGLISH 6 - Q4 - Wk7 - USLeM RTPtrishajilliene nacisAinda não há avaliações

- Nur Writing - Marilyn JohnsonDocumento4 páginasNur Writing - Marilyn Johnsonyinghua guo0% (1)

- Clinical Practice Guidelines - 2017Documento54 páginasClinical Practice Guidelines - 2017Cem ÜnsalAinda não há avaliações

- Mood Disorders - Psychology ProjectDocumento16 páginasMood Disorders - Psychology ProjectKanika Mathew100% (1)

- Calcium Hydroxide, Root ResorptionDocumento9 páginasCalcium Hydroxide, Root ResorptionLize Barnardo100% (1)

- Nutritional Considerations in Geriatrics: Review ArticleDocumento4 páginasNutritional Considerations in Geriatrics: Review ArticleKrupali JainAinda não há avaliações

- STS Activity-18 Research-ActivityDocumento2 páginasSTS Activity-18 Research-ActivityEvan Caringal SabioAinda não há avaliações

- Supplement Guide Memory FocusDocumento41 páginasSupplement Guide Memory Focusgogov.digitalAinda não há avaliações