Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Protocols For A Post Capitalism World Section 8 The Crash, Debt, Accumulation, Financial Capitalism

Enviado por

CouzeVenn1Descrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Protocols For A Post Capitalism World Section 8 The Crash, Debt, Accumulation, Financial Capitalism

Enviado por

CouzeVenn1Direitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

1 Protocols for a Postcapitalist World. Couze Venn Section 8. Bankrupt Capitalism: Debt, the crash, and neoliberal accumulation.

The analysis presented here draws from a number of prominent recent analyses of what went wrong to highlight the key developments which have combined to trigger the crash. It shows that crucial changes in market practices, in the mechanisms of regulation and in values promoted by neoliberalism, together with the application of new communication technology in transactions on the global financial market, have resulted in the institutionalisation of risk as a technique for generating hyperprofit. It argues that a key part of the changes is the commodification of debt that now operates as the latest stage in the process of accumulation described in earlier sections. It also explains how the principle of shareholder value maximisation feeds upon the debt economy whilst feeding into the bonus culture. Together these components of financial capitalism necessarily result in the intensification of inequality. At the end, the paper summarises points from the broader critique of capitalism before outlining some ideas for alternatives to capitalism. What is presented here is part of a larger work which locates capitalism in a longer history, establishing the reasons for the reliance of capitalism on neverending accumulation and growth, its character as a zero-sum economic game, and its fixation on consumption. That larger work details the consequences of this economy for resource depletion, environmental degradation, the threat to biodiversity, and the dominance of harmful technologies. It argues that since the ending of the second world war, the neoliberal project has aimed to put private interests and business rationality in charge of both the economy and social policy, involving the elimination of the idea of the general good; this has now been achieved through the dismantling and privatisation of commons and public services, the universalisation of an audit culture and the subversion of democracy. The conclusion develops a number of protocols which can guide the invention of new forms of convivial and cooperative socialities and radical democratic forms of governance. The outline of this larger work can be imagined from the list of sections into which it has been divided: Part 1. Section 1. A confluence of crises: Economy, environment, ecology, resources (1-20). 2. Four scenarios for the future (20- 24). 3. Living on a small planet: Limits to growth (24-28). 4 The political economy of growth: Accumulation, dispossession, global markets and liberal capitalism (2834). 5.Throughput and commons: challenging accounting practice (34-39). 6. Property and commodification: The common good versus private interest (3946). 7. The roots of inequality: zero-sum economies, pauperisation (46-50). 8. Bankrupt capitalism: The commodification of debt, the crash, and neoliberal accumulation (50-65).

2 A. Financial capitalism. Tricks of the trade and the makings of the super-bubble. The crash of 2008 was in many ways a disaster foretold. This is amply demonstrated in the analyses by Roubini and Mihm in Crisis Economics (2010), by Gillian Tett in Fools Gold (2010), Joseph Stiglitz in Freefall (2010), Christian Marazzi (2010) in The Violence of Financial Capitalism and David Harvey in The Enigma of Capital (2010), whilst the description of events in Michael Lewis The Big Short (2010) and George Soros The Crash of 2008 and What it Means (2009) adds further insights into the calculations and assumptions motivating the players in the world of finance. Tett for example, who as assistant editor at the Financial Times observed close-up the dizzy credit boom leading up to the crash, points to the high risks the derivatives sector already carried, risks she had warned about from 2005, though politicians, policy makers and those whom Andrew Glynn (2006) denounced as the dominant orthodoxy were taking no notice of what the derivative market was doing to the economy. For more than thirty years, financial innovations introduced from the 1970s (Harvey, 2010: 262), and credit derivatives in particular, had progressively weakened the financial stability of the global banking system (see also, Lee and LiPuma, 2004) by hyperinflating the value of liquid assets circulating in the world economy, whilst capital assets holdings, such as buildings, land, machinery, raw materials, grew at a modest rate. The growing imbalance along with shifts in the world economy namely, deregulations (such as the Big Bang in 1986 in the UK) which freed the financial sector from adequate surveillance, the commodities boom, the rising economic powers or BRICs, fluctuations in the exchange rate system - fed into what Soros (2009) has described as the super-bubble that triggered the crash. The same forces have acted as a driver in the scramble to privatise public utilities and commons, in the Third World to begin with (Venn, 2006a, 2006b), now extended to the developed economies, with adverse effects on the strength of infrastructures. Tett summarises the situation when she highlights the following factors in the financial mismanagement: Poor mortgage regulation, global savings imbalances, a failure of bank oversight, lax credit ratings, a crazy consumer debt binge, as well as excessively loose US monetary policy (2010: ix). She notes that by 2005 the credit derivatives markets amounted to $20 trillion, and AIG, which crashed in 2008, had over $400 billion worth of derivatives on its books (op. cit: x) - money for which ordinary people have been billed as the major component of the rescue package devised by the very institutions which broke the economy (see also the analysis of derivatives and risk in Venn, 2006b). This basic picture is confirmed by the analysis by Roubini and Mihm Roubini had been warning about the impending catastrophe from 2006 - who stress the deep structural origins of the crisis ... showing how decades-old trends and policies created a global financial system that was subprime from top to bottom. Beyond the creation of ever more esoteric and opaque financial instruments, these long-standing trends included the rise of the shadow

3 banking system, a sprawling collection of nonbanks mortgage lenders, hedge funds, broker dealers, money market funds, and other institutions that looked like banks, acted like banks, borrowed and lent like banks ... but were never regulated like banks (Roubini and Mihm, 2010: 8). From an historical point of view, it is instructive to recall Karl Polanyis observation that financial innovations have been a central component in every crisis which has beset Europe for centuries (Polanyi, 2001 [1944]). This is underlined in Roubini and Mihms analysis when they point to the many other examples and the similarities between them, for example, the fact that most begin with a bubble ... (which) often goes hand in hand with the excessive accumulation of debt, as investors borrow money to buy into the boom ... asset bubbles are often associated with excessive growth in the supply of credit (Roubini and Mihm: 2010: 17ff). In that respect they note the following cases: the tulip mania of 1630, the John Law Mississippi Company in 1719, the South Sea Company bubble of 1720 , and global crashes such as in 1825 which incidentally led to the New Poor Law Acts of 1834 and the workhouse in England (Ashurst, 2010; the current crisis may well lead to a similar criminalisation of the undeserving poor) the global meltdown of 1873, and the Great Crash of 1929. Major technological innovations such as that of the railroads or the creation of the Internet are sometimes the trigger too, as they point out, although the most destructive booms-turn-bust have gone hand in hand with financial innovations (2010: 8). Institutions and measures put into place after the great depression e.g. the Bretton Woods institutions (World Bank and IMF), central banks acting as lender of last resort, the Basel Capital Accord stipulating the ratio of capital to assets for banks, etc - were supposed to help regulate markets to prevent such crashes and mitigate the effects of minor contractions in the world market. But free market fundamentalism dictated a phase of deregulation, whilst new structures of incentives and compensation ... channelled greed in new and dangerous directions (Roubini and Mihm, 2010: 32). The crucial element to add to the brew is debt-financed consumption, for, not only has it fuelled economic growth (op. cit: 18), it has also fed into the vicious cycle of borrowing and spending by the population at large, creating irrational euphoria oblivious of the risks (op. cit: 14). I think it is important to stress the role of innovations in communication technologies - greatly neglected in analyses of the crash - particularly that of the ticker tape in relation to the 1929 crash and the computer and digital communication technologies during the boom founded on derivatives and collaterised debt. An idea of how this operates is given in Knorr-Cetina and Brueggers (2002) analysis of the intimate dynamics coupling players and technologies in determining practice on the financial market such that a particular socio-technical world is constituted which locks traders into a a selfenclosed culture which can become dysfunctional, as Tett (2010) has argued (see also, Venn, 2010 on the affective aspects of this process). I shall examine below the effects of algorithms and algotrading in adding a new dimension and major new risks to trading on the financial market.

4 These changes in the economy, together with the bonus system, examined below, encouraged the invention in the USA and the UK of new financial instruments such as credit default swaps - a CDS is a kind of insurance policy on the risk of credit, transferring such risk from purchaser to lender for a regular fee paid to the seller; CDSs are traded over the counter, even when the buyer of the swap does not own the debt they are insuring. Securitization by means of instruments such as credit default swaps, which reached a notional value of $60 trillion by 2008, became one of the most important sources of systemic risk (Roubini and Mihm, 2010: 75); CDSs are often linked to short selling, the latter being the trick whereby the seller gets their money back if the insured security actually defaults, which encourages all kinds of dishonest trading and creates havoc, as in the case of Lehman Brothers going bankrupt in 2008, and when the market is volatile and thus prey to vultures. Indeed, volatility is a necessary component encouraging betting or risk-taking (and its sub-contracting) on the financial market. Stiglitz points out that CDSs were in reality as much designed for deceiving regulators (2010: xviii). CDSs yielded staggering profits and bonuses, adding to the host of other innovations: interestonly mortgages, teaser rates, loans on securities deriving their values from these assets via instruments and vehicles for leveraging the value of these loans. It could be argued that today, in spite of the crash, key players (such as credit rating agencies) are inducing volatility in the global economy to create situations which allow the lucrative trade to continue, for example, regarding sovereign debts (analysed below). And one should also point to the new trading instruments like exchange traded funds (ETFs), now amounting to over one trillion dollar, which have been compared to the toxic instruments that led to the crash (Wachman, 2011). In the period leading to the 2007/2008 crash, Securitization was the name of the game (Roubini and Mihm, 2010: 33), whilst banks and other financial institutions made loans regardless of the applicants creditworthiness, then proceeded to funnel the loans mortgages, auto loans, student loans, even credit card debt to Wall Street where they were turned into increasingly complex and esoteric securities and sold around the world to credulous investors incapable of assessing the risk inherent in the original loans; towards the end, loans in the USA were even extended to NINJAs: those with no income, no job, no asset (2010: 65). Securities came in a bewildering range of forms: collaterized mortgage obligations (CMOs), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), and combinations of CDOs assembled in the labs of Wall Street to produce CDOs of CDOs; there was even a synthetic CDO made up by combining a number of credit default swaps to mimic an underlying CDO (2010: 67). Tett sees the latter - called Bistro as a key innovation in the business of securitization and leverage, making possible the linking of derivatives technology to securitization (Tett, 2010: 59, 60). These financial products were so fiendishly complex that financial firms used models applying sophisticated mathematics (chaos theory, complexity and probability theories) to value them (op cit: 66, 67). Indeed, the algorithmic architecture of the models internalises through its very operation the propensity

5 to inflate the value of the virtual money-capital generated in the derivatives market. Furthermore, through the codes encrypted in the algorithms, the flaws in the assumptions made by economists and traders are hardwired into the system, yet remain invisible and so difficult to correct. So, for instance, once risky loans are coded as secure assets then alchemically transmutated into desirable securities through their mathematisation, traders could rely on the system to generate the multiplying profits and not worry too much about the problems stacking up. Viewed in this light, it is a sobering to realise that currently Seventy per cent of trading in the US stock market is algo trading executed autonomously by computer algorithms (Kevin Slavin, 2011: 28). These models, besides, assume neverending growth, and could only be sustained if one made that assumption, and investors around the world shared such assumptions. Credit agencies too which benefit directly - bought into the system and so helped the trend rather than acted as a brake: ratings agencies Fitch, Moodys, Standard & Poors could have and should have prevented this from happening. But they too made hefty fees from securitization and were more than happy to help turn toxic loans into gold-plated securities that generated risk-free returns (Roubini and Mihm, 2010: 33). Yet, the faultlines in financial capitalism were not the consequence of ignorance and the credulity of speculators alone (who were focussed on making a quick profit), for, as many analysts have shown, they were the product of a policy of deregulation pursued from the early 1980s as part of the neoliberal and the neocons determination to reconstitute a post-Keynesian framework for a free market economy. It was a policy supported or initiated by many players in the field: the Reagan administration, the Thatcher government in the UK which liberated the financial system from established mechanisms of regulation (the Big Bang event), the Washington Consensus, Bretton Woods institutions, Alan Greenspan who was the neoliberal chairman of the Federal Reserve in the USA from 1987 (and at one time a member of the inner circle around Ayn Rand, thus linked to Friedrich Hayek and the Mont Pelerin Society think tank promoting neoliberalism from the 1940s). The wider context includes the Cold War, and thus the ideological battles being fought across the world, not least in economic theory, whilst Western foreign policy in the period destabilised or crushed attempts to establish alternative and more egalitarian economies in the Third World in particular (with tragic and barbarous consequences in Allendes Chile, and throughout Latin America, destroyed by military coup, the extermination of the Left, and the work of the Chicago Boys ). They combined to produce monetary and fiscal policy derived from neoliberal doctrine, whilst American hegemony over global finance and the world economy, cashed out in the unilateral establishment of the dollar as reserve currency in 1971, further added to the pressures on national economies to conform to the new rules of the game or face direct intervention and annihilation (say, as happened in ex-Yugoslavia). B. The debt society: The commodification of debt, and accumulation through the new form of rent derived from it.

6 In order to avoid the temptation to individualise the failures, or think that greed alone and a number of crooks in the system were responsible for the catastrophe, it is important to note that the signs of the revolution were present earlier, as we can gather from the analyses of Michel Foucault (2008) in his Lectures of 1978-79 The Birth of Biopolitics, and of J-F Lyotard (1984 [1979]) in The Postmodern Condition, both of whom made visible the trends already in process at the level of discourses and state mechanisms following structural transformations in the global economy from the 1970s and significant shifts in the vision of (post)modernity at the time. Lyotards insights concern the recognition that the transformations taking place in the domain of knowledge and cybernetic technology were making possible the commodification of knowledge in the form of informational commodity indispensable to productive power (1984: 5), enabling knowledge to appear as a product for commodity exchange; this shift is a central component of the so-called knowledge economy. For example, in the field of financial capitalism, one can see this mechanism at work in the way financial products are detached from the asset base in the form of digital information to which value accrues as it circulates on the market. Lyotard also associated these transformations with a crisis in the role and stability of the state because of the circulation of capital that go by the generic name of multi-national corporations (1984: 5), a process he links to geopolitcal shifts, including the probable opening of the Chinese market and the decline of the socialist alternative (op. cit: 6). He in fact noted the weakening of the administration, the minimal state, the decline of the Welfare State as features of this crisis (op. cit: 87, note 22), goals which neoliberalism had pursued from the 1940s (Section, 1). The by-passing of democratic mechanisms of accountability and decision-making by a technocratic and bureaucratic elite say in the recent eurozone crisis - is a logical consequence of the weakening of the role of the state. One finds similar arguments about the relationship between the biopolitical state and neoliberal discourse in Foucaults genealogy of liberal political economy where he points out that the new doctrines originally derived from the Austrian School of (ordoliberal) economists, notably, L. von Mises, F. Hayek and others who stressed competition as dominant principle, and argued against government intervention and socialist social policy such as the welfare state (2007, 2008 [2004a and b]; see Sections 4, 6). They also promoted economic policy which would allow weak firms and banks, however big, to fall rather than live on as debt-laden zombies fed on state funding and borrowings (Roubini and Mihm, 2010: 54-59). It must be noted though that, as Harvey (2005) points out in his analysis of these key features of neoliberalism, there are contradictions that undermine the boasted rationality and coherence of the system, the failures of which have often been offset in practice by a dose of pragmatism. Notably, this has meant that in the real world it has been necessary to allow state intervention in the form of central banks acting as lender of last resort, to counter when necessary the inherent instability originating from financial institutions, or to promote state investments in infrastructure and in

7 stabilising the level of consumption, measures that in effect subsidise free enterprise by way of throughput (Tim Jackson, 2009, see details in Sections 5 & 6). Roubini and Mihm explain the necessity of this component of the financial system by reference to Minskys (2008 [1986]) neo-Keynesian theory regarding the role of financial intermediaries in knitting together various players in the economy and by reference to what Keynes called the veil of money whereby money both generates growth yet introduces instability through accumulating debt in modern economies (2010: 50, 51). Debt was a key factor in Minskis analysis too; as we know, it was central in the crash, fed in the USA on easy money (very low interest rate), and sub-prime high-risk lending. But it was the whole framework and the banking culture noted by Tett (2010) that enabled debt and credits of all kinds to become leveraged assets and enter into the new circuits of financialisation that hyperinflated them by way of an endogenous multiplier effect until the bubble burst. The same point is amply made in George Soros diagnosis of the problems already stacking up in the global economy from the time when market fundamentalism became the guiding principle of international financial system (2009: 95). I think it is impossible to understand the present predicament without unpacking the central role played by debt and its circulation or flow in the new stage of accumulation which responded to crises in the 1970s by trying to reverse the redistributive technology and the apparatuses of social welfare and social insurance put in place from the time of the New Deal in the 1930s. The Welfare State system implemented after the war had a central redistributive goal, and had successfully narrowed the inequality gap in favour of the general population in most countries a strategy which ordoliberals had condemned as socialist social policy (Foucault, 2008: 144; see Sections 4, 7). In order to cast a new light on the emergence of the new regime of debt which was part of the neoliberal reconstruction of the economy and society, I will relocate it by reference to the longer historicisation which I outlined at the beginning of this study. This is because this longer history enables the mechanisms of financial capitalism to appear as the latest stage in the cumulative phases of accumulation and commodification which I discussed there, namely: primary, primitive, capitalist and informational phases or stages, adding to what Arrighi and Braudel have described as cycles of accumulation that chart the long cycles of decline and growth and the shifts in the centres of economic power that they have correlated to such cycles (Arrighi, 1994: 23, 24; see Sections 1, 4,7). The more immediate background includes the economic crisis of the 1970s, structural problems including the growth of global corporations, and significantly, the fall in the share of the national income taken by top 1% of earners since the 2nd world war (from 16% to 8% in the USA, as Harvey points out, 2005: 15), and a steady decline in the percentage of wealth held by the top 1% of the population in most advanced economies, with a steep decline evident in the 1970s in the USA (Harvey, 2005: 16 ff.). The policy changes introduced from the 1970s, and particularly from the era of the Reagan and Thatcher neoliberal governments, principally, the reduction in the US of top rate of tax from 70 to 28% and a massive cut in corporation tax (Harvey, 2005:

8 26), produced the desired effect of redressing the balance of inequality in favour of the very rich: by 1996 the net worth of the 358 richest people was equal to the combined income of the poorest 45% of the worlds population 2.3 billion people (United Nations Deveopment Program, 1996, 1999, cited in Harvey, 2005: 35), whilst real wages drastically fell from the 1980s (Harvey, op. cit. 25,26). When analysed in the light of the longer historicisation of dispossession described in earlier sections, the promotion of a credit boom is revealed to have been a measure designed to offset the effects of the fall in wages, since borrowing functioned as replacement for earned income and borrowers were encouraged to consume on credit, which stimulated growth in the economy as a whole. As we saw, the commodification of debt in the form of derivatives that could be traded as independent financial products was part of this logic of generating value to feed into the process of accumulation. It fits neatly within the system whereby money is made to create more money without passing through a phase of commodity production, a process Marx described in terms of M-M where money (M) functioned as a fictitious commodity (Marx, Capital 1, and 1994, examined in Section 4). This process is the opposite of the classical CM-C circuit describing the process of production and circulation of commodity in which money functions as mediating and productive force. It is important to point out too that the mediation through a phase of production and trade is slow, whereas the systems invented in the period of the financial boom are characterised by unimpeded flow and speed; as the Physiocrats already knew in the 18th century, the faster the circulation, the greater the profit. We know from the crash that the grounding of debt on housing and property as a key asset driving borrowing, and the encouragement of workers to enter the property market and thus become debtors, greatly inflated the value of property, feeding back into the cycle of excess. We therefore need to add another phase in the process of the generation and accumulation of value, in which debt plays a central role, namely a longer chain of circulation or circuit linking debt to consumption whilst generating value for extraction by creditors or holders of capital. This can be expressed in the formula M - (D-C) - M, where D stands for debt and C for commodity. So, debt in the debt society is the element which feeds the self-generation of money by money, appearing in effect as a new form of rent. There are thus two related components of the debt society: value extracted from virtual capital, or technologically immaterialised and dematerialised assets, by way of this new form of rent, and property and commodity functioning as the objects of desire or means of capture for ensnaring the consumer into becoming debtor.

B.1. Sub-contracted taxation, or the state as debtor of last resort. A number of important issues lie behind these developments which throw vital light on contemporary capitalism. The first question is: what strategy can the financial sector invent, given that sub-prime and easy money has dried up, to

9 replace credit and property or housing as the sources for further generating hyper-profit? As it is now generally recognised, part of the solution to the crash arising from the credit bubble has been to displace the cost of the fallout onto ordinary workers or the 99% of the population by extracting an extra charge from them. But the really clever answer has been to put the state in the position of collective borrower - one could even say: as debtor of last resort. In effect this move makes the state function both as debt collector and as cash cow for the financial sector and transnational corporations. As we shall see, the crisis has provided the opportunity for neoliberalism to complete a process initiated three decades ago. We know that neoliberal doctrine seeks to minimise the economic role of the state as well as eliminate the redistributive policy pursued by the welfare state to equalise opportunities and reduce the inequality gap. Liberalisation over the last thirty years in many parts of the world has already achieved a significant degree of transfer of responsibility for common pool resources and public services from the state to the private sphere, whilst marketisation introduced accounting practices founded in market values and calculative rationality in reshaping practices in the public sphere. The developments in process now are reducing the state to the role of middleman for extracting value from the public in more direct ways, bypassing the obstacle presented by the fact that private corporations have no legitimate authority to impose taxation on the public this is one of the aspects of the distinction between public and private interest discussed in Sections 5&6. This new process of extraction of value takes several forms, first, quantitative easing, that is, the creation of money by central banks to refloat the financial sector. Basically this works in the following way: the government sells bonds to banks and corporations and the central bank buys the financial assets to increase the money supply in the hope the money is loaned by the financial sector to businesses to stimulate the economy. But the amount of money created through this artifice ends up as government debt, thus increasing state deficit, whilst the advantage for owners of capital and creditors is that QE generates interest payments for them as the loans circulate, that is, QE ends up as a new source of rent. Second, since the increase in state deficit forces it to impose new taxes and further reduce real wages in order to pay for the debt, we have a situation in which the state acts as sub-contractor for taxing the population on behalf of financial capitalism. This sub-contractor role of the state in neoliberal capitalism can be extended to the analysis of the strategies whereby the state collects taxes to hand over to private enterprise for supplying services which either the state used to undertake (as part of responsibility for throughput or infrastructure, say hospital provision), or should do (say, schooling for those entitled to free education). In the UK, this has been achieved through schemes such as Public Private Initiatives, and so-called free schools, and partnerships of one kind or another whereby corporations directly benefit whilst costs spiral, quality of services plummets, and accountability is curtailed by the conditions stipulated in legally binding contracts.

10 Third, the strategy involves putting pressure on all states, including technically bankrupt, or sub-prime states like Greece and Ireland, to reduce the deficit by borrowing at premium rates, slashing public expenditure to pay for this, and adopting neoliberal policies of structural readjustments, again benefiting the banking sector and transnational corporations. Fourth, forcing the state to sell off public assets at bargain prices to the benefit of corporations (a recent example is the selling of the nationalised bank, Northern Rock in the UK, at a loss for the government). These two strategies have an interesting parallel. For, in the 1980s, African and Latin American countries were directed by neoliberal global institutions to adopt austerity measures and sell off public assets, or liberalise them, to reduce sovereign debts resulting from so-call aids programmes. The result has been clear reductions in per-capita income and increases in poverty and inequality in most of these countries, as well as a negative effect on economic growth, as many reports have detailed (see also, Venn 2006a). And finally, the ongoing strategy which is being put in place to eliminate the risks of default or at least to minimise it is that of obliging healthier economies such as Germany with regard to the European economy to act as guarantor. In fact, what is appearing is the extent to which risk has become institutionalised into the mechanisms, for the mathematics of chaos and probability theory requires integrating risk as a positive parameter in the calculus whereby the chance of a greater return or hit can be improved. In order for this game of speculative hedging to become relatively safe, states, as debtors of last resort, need to be put in a position of having to secure or insure the risk, paying for the cost or premium through squeezing a greater income from the general public. As noted earlier, it could even be suggested that it is in the interest of financiers to trigger instability in the economic system and some actions, say by credit rating agencies, appear to confirm this - since such performative instability simulates conditions for lucrative trade on the financial markets. Altogether, what this range of mechanisms reveal is that they all contribute to the intensification of dispossession. An incidental feature which is worth highlighting is the fact that the state in neoliberalism, whilst appearing to shrink in relation to having direct responsibility for providing services which enhance the general good, now reappears as but an agent of capital, acting as a willing or unwilling middleman in the process of transferring wealth from the people to owners of capital. This is consistent with Braudels argument that capitalism only triumphs when it becomes identified with the state, when it is the state (Braudel, 1977: 64, 65), with the proviso that this works if the state is divested of the power to question market practices and values (see Section 5 regarding the vital role of an audit system in that process). The institutionalised hegemony of neoliberalism together with the insiduous power of corporations, including media corporations, operating through the lobbying system ensure this subversion of democratic accountability.

11 The conclusion from the mix of fiscal and monetary policies devised to deal with the fallout from the crash is that sovereign debt now functions both as the instrument for bailing out the failed financial system, yet at the same time state borrowing from financial institutions is made to sustain the level of hyperprofit for the financial sector previously generated by the credit bubble. Instead of individual households and borrowers as losers in the zero-sum game of enrichment, it is now the state which acts as collective borrower, lender of last resort and the mechanism for sqeezing more from the already hard-pressed public. The dominant orthodoxy in economic thinking plays a crucial role in these changes by lending authority to the experts who advocate the strategies put in place. These same experts are now implementing these policies, having long secured control over the decision-making hubs - IMF, European Central Bank, the Federal Reserve System, WTO, central banks, centres of economic policy, think tanks and in their capacity as government advisers, heads of major corporations and, in the latest developments, heads of governments, as in Greece and Italy (see Vallely, 20.11.2011: 39). No one except the financiers, owners of capital and top management gain. Of course, unless radical change is made in the rules of the game, the debts or deficits accumulated by sovereign states can keep on feeding the process of dispossession and accumulation for years to come. This new regime of debt in the process of accumulation shows the dependence of neoliberalism in practice on the state as a central mechanism for dispossession; the efficacy of the state in this process clearly goes beyond ensuring security and establishing the laws that institutionalise the rules of the economic game, say, regarding labour and property laws (Foucault, 2008, on the role of law in neoliberal governmentality, see also Terranova, 2009). In a sense what is emerging is a neo-neoliberalism or neoliberalism 2.0 in which the state has become subservient to capital, even if it still retains a coordinating and mediating role at the level of social policy and security. From the point of view of the current crisis, I would highlight the following features of the framework or conditions of possibility for the neoliberal regime of debt: 1. The benefit which the American economy has derived from running a deficit budget for some time, made possible by the privileged position of the dollar as reserve currency in the world economy and American domination (and sole right of veto) over the World Bank and the IMF, a position institutionalised by the Bretton Woods financial rules of the game. 2. The extraction of wealth from Third World countries by means of debt financing arising from so-called aid, that is, mainly interest-bearing loans which increasingly crippled their economies, especially as interest rates increased in the 1970s (See Susan George A Fate Worse than Debt, 1990). It could be argued that this situation helped to shape the financial imaginary which generated what has been instituted in the form of derivatives, for it provided the exemplar of a mechanism for transferring wealth to holders of capital through finance: part of the aid package consisted of lending money to poor countries so that they can buy goods and services from the creditors (with strings attached), which is exactly the same thinking that motivated the credit boom.

12 It is worth noting in this respect that at the Bretton Woods discussions in 1944, J.M. Keynes argued unsuccessfully for more flexible arrangements which would have equipped the system with built-in policies for rebalancing the burden of debt and deficit accruing to debtor nations; instead one has seen the growth of odious debt which has massively advantaged creditor states, as Keynes had warned. Relating to this point, it could be argued that Greece and other countries are being boxed into that same vicious circle of debt by current so-called rescue packages devised according to the same rules of the game. 3. The question of interest and its history, for instance, its role in amplifying debt, and thus in increasing inequality. Interestingly, because of the disparity in wealth that interest on loans creates, usury was prohibited in early Christianity and Abrahamic religions generally, and remains so in Islamic principles, precisely because of its effect in increasing inequality, with divisive consequences for the community of believers (Joxe, 2002).

B.2. The politico-theology of debt. So, a number of important ethical and political issues are concealed in the question of particular regimes of debt and interest which the wider framework of analysis must bring to light if one is to avoid both the repetition of pauperisation and the destructive effects which systemic inequality has for solidarity and convivial social worlds. Following Joxe (2002), I would point to the history of the periodic cancellation of debt in Greek city-states and early Jewish communities that he discussed in Empire of Disorder, an annulment which aimed at the restoration of the social bond and securing the conditions for a democratic polity; a more recent study is that of David Graebers Debt: The First 5,000 Years (2011). For Joxe, what was at stake in the adoption of this strategy by the early Christians was the proclamation of the liberty, equality and fraternity of all Christians, who were thus redeemed, in other words freed from slavery , to use the vocabulary of the period (Joxe, 2002: 116, and 114-117, discussed in Venn, 2006a : 167). In developing this point, Joxe makes the important observation that the Latin version of the Lords Prayer, still used by the Pope, makes no reference to trespasses or the forgiveness of sins but appeals to God to forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors (Matthew 6: 9-13). The shift from debt to sin (which first appeared in Lukes 11: 2-4 version, but has become widespread, and is used in the Book of Common Prayer) inscribes a crucial ethico-political lesson in the light of the shift from the priority accorded to social and political objectives, evident in the motivation driving the cancellation of debts in early Greek and Jewish traditions, to a morality fixated on the dubious claims of originary imperfection, genetic determinism, natural order and ontological deficiency. It could be argued that underneath this historical shift is a chain of signifiers that has gradually come to link debt to fallenness through the idea of sin and its metonymies, such as wilful inadequacy, laziness, dysfunctional behaviour, underdevelopment, inferiority, and so on. It is a worldview (and an

13 imaginary) which in the minds of policymakers authorises the criminalisation of indebtedness - though it is usually the result of poverty - and so justifing punishment or exclusion of one kind or another. It is astonishing to think that these attitudes and values, found in Utilitarian thinking in the 19th century, for instance in Malthusian social policy and the values that shaped the New Poor Laws of 1834 in England and the treatment of the poor generally, are precisely the values which are still dominant amongst (neo)conservatives today. They continue to shape the imagination determining neoliberal social policy and realised in many forms of exclusion, or indeed killing, if we follow Foucault in understanding the term thus: When I say killing, I obviously do not mean simply murder as such, but also every form of indirect murder: the fact of exposing someone to death, increasing the risk of death for some people, or quite simply, political death, expulsion, rejection, and so on (2003: 256). Could one conclude that in the minds of the rich, the poor, that is, the losers in the zero-sum economic game, owe a debt which necessarily bankrupts them since it can never be repaid? It is clearly not the ontological indebtedness which is inscribed in the face of the other in the Levinasian problematic of being, according to which the face relation stands in for the unexpressed demand of responsibility which the other always-already makes of us. Such an ontological debt, arising from ones inherent condition as a social being and as an essentially vulnerable and fragile being, necessarily leaves us bereft because of the burden of responsibility for the other which it places upon us, a responsibility which can never be completely discharged since it calls for a generosity that entails the sacrifice or abnegation of the self (Levinas, 1969, 1984; Derrida, 1992, also Ricoeur, 1992, elaborated in Venn, 2000). So, on the one hand, we have the givenness of an original gift outside the sphere of exchange, thus outside accounts: the gift of life, the world, oneself, responsibility-for-the-other- related to grace and caritas in Christian onto-theology (and in Augustinian discourse) - and, on the other hand, we encounter Ayn Rands neoliberal, neoconservative and egocentric individualism at the heart of The Virtue of Selfishness and the interest it charges that in the end bankrupts us all. Two different conceptualisations of human beings and society are at stake in these different regimes of debt: one supporting an ideal of mutuality and respect for each life, and the other fixated on enrichment and the satisfaction of the self at the expense of others; the former nourishes and comforts, the latter kills. There is another aspect of the new regime of debt which must be brought out. We have seen already that the components establishing the commodification of debt start with the range of borrowings and credit arrangements that constitute loans. These include familiar transactions such as capital loans to firms and individuals, credit cards purchases, inter-bank lendings (framed by the LIBOR), state to state or to bank lendings, and loans made to member states by global inter-state financial organisations like the IMF. We saw too that the noxious phase happens in the accumulation machine when some categories of loans are coded into the kinds of securitised products or derivatives described earlier, that is, collateralised debt obligations, credit default swaps,

14 and so on. Once they are detached from the initial assets against which the loans were secured, they can then be traded as a special kind of commodity. As I noted above, the financial instruments invented to circulate and distribute the debt have been set up to accelerate and multiply the value of the original debt, thus having an endogenous multiplier effect already encrypted into the process through the algorithms that power the trade. The key aspect of the situation worth highlighting is that in a good deal of contemporary financial capitalist transactions, the original money-capital is virtual capital (and a fictitious commodity in Karl Polanyis understanding), a feature that encourages the fantasy (and indeed quite crazy) world of derivatives trading, as the accounts of practices described by Tett, Lewis, Roubini and others have shown. The trouble, as I noted, is that the coding process hardwires initial assumptions into the system, including faulty assumptions about the level of risk associated with the original loan. This occurs through the algorithms used to programme the coded financial products into digitalised information which computers (i.e, information processing machines) simply read and act upon. These programmes in the form of algorithms make the products available as autonomous commodities for circulation and trading on the global financial markets: the faster the speed of circulation, the more value is extracted. If we follow this logic to its conclusion, it could be argued that through cybernetic and financial technology, it is time itself which has been commodified by way of its informationalisation and circulation as value (Venn, 2006b); it is a move similar in some respects to the commodification of knowledge through its informationalisation, as Lyotard (1984) argued. One can extend this analysis to propose that what the digital and algorithmic mechanisms (or dispositif) make possible is the topological relaying of debt, time and value in the form of money. This would mean that through its informationalisation, money has become the form into which time and value can be converted such that, topologically, each can be smoothly transformed into the other: and so, finally, time is money. This artifice enables the infinite character of time to be folded into capitalist economy, thereby making it possible for the unlimited tendency for accumulation, for consumption, already immanent in liberal capitalism, to be bolted onto the drive for unending growth and the Smithian goal of unlimited enrichment (as explained in Section 4). Thus has an excessive dimension been encrypted at the heart of the global economy through a new technologisation of finance and communication. A line of thought which merits further elaboration is the proposition that what the analysis reveals is the intimate interconnections between this regime of debt and the economy of lack in the ontological and psychoanalytic sense, the latter doubling with the economy of excess which is its other side: here, in the form of opulence/surplus, compensation/security. It could be argued that underlying this economy of a limitless hunger, one finds a more intractable process that links ontological insufficiency, indebtedness,and insecurity to a yearning for life that takes historically divergent forms. It would be fruitful therefore to examine to what extent a socio-political unconscious operates at

15 this level of psycho-social structures of subjectivity, invisibly motivating ones behaviour in the world. One implication is that these transactional affinities suggest the need for a psychopathology of capitalism to bring to light the psychoses which it overdetermines and sustains; this is an exploration began by Deleuze and Guatarri in Capitalism and Schizophrenia, and Stiegler (e.g 2004, 2008, 2009) in his analysis of consumer culture by reference to its capture, and perversion, of libidinal energies. In outline then, the new form of the accumulation of wealth consists of the following components: neoliberal hegemony at the level of economic and social policy, cheap and often toxic if irresistible loans; a profusion of credit arrangements; technological wizardry which has given birth to an informational form of capitalist accumulation; lax regulation; unscrupulous players; credulous or careless borrowers; a global market in which mafia or feral capitalism has found rich pickings and boltholes/tax havens; ignorant or blinkered regulators and officials; politicians only too happy to take credit for the (hyperinflated/addictive) boom and/or fixated on the compulsive repetition of failed doctrines; and an essentially excessive project or desire which has found its existential and technological incarnations in the new machinery of financial capitalism and consumer culture. Together this assemblage operates the commodification of debt to generate value or wealth which is appropriated in a new form of rent; given the incredible multiplication in the values generated by the mechanism outlined, surpassing anything seen before, the accumulation of wealth obtained through this latest addition to forms of dispossession introduces a new dimension in world economy, measured in the massive increase in the gap between rich and poor - discussed earlier by reference to the work of Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) and many others (sections 1 & 7) - and massive costs for resources and the environment. My point is that the infernal system which has broken the economy is fundamentally inhuman. This is starkly illustrated when we recall the dominance of the financial markets of London and New York by algo trading, that is, trading which is generated automatically and autonomously by the algorithms already programmed into the network of computers linking financial agents/players across the world. Indeed, algo trading today mostly consists of high-frequency trading (HFT) which involves moves and decisions that are too fast for human traders to effectively follow or control, suggesting a system which has become automated and independent of human will yet commands decisions by organisations. A striking example demonstrating the surreal character of this situation is the recent plan by the New York Stock Exchange to build a new transatlantic cable costing $300m to reduce the transit time of stock trading between London and New York by 6 milliseconds from its current 65 milliseconds, the reason being that the algorithmic operations performed by computers are so fast that traders now want information to be transmitted instantaneously (J. Hecht, 2011 - New Scientist 01.10.11: 24). In effect, we are today faced with an economy which has become inhuman or at least psychotic at its core. Whilst the arcane assemblages alchemically generate vast fortunes for

16 a few, the room for meltdown is equally scary, as happened on the 6th May 2010, with a Flash Crash on the New York market. In summary, the analysis has shown how the new phase of accumulation established through the commodification of debt to generate new wealth in the form of rent has produced another mechanism whereby money-capital (M) makes more money (M) without passing through the stage represented by the production and circulation of (material) commodities. Unpacking this process has revealed the role of a regime of debt and new financial and communicational technologies in grounding it. The fuller picture recognises that the mediation of M to M via debt (D) also indirectly generates consumption, and in the case of loans to firms, production - plus of course inflated compensations and bonuses. So, there are two related mechanisms driving the propensity to consume and the maximisation of profit. Although the picture is complicated by inter-bank (including central banks) and inter-state loans, for our purposes it is the M-M circuit of financial capitalism which is of particular interest as it plays by far the most effective part in generating hyper-profits and bonuses via the regime of debt on which it depends; it also acts as feeder for a culture of excess for the rich: the latest figures show that the luxury goods and high-end property sectors are booming (Guardian, 24.10.2011). C. Sick capitalism: The bonus system, shareholder value maximisation, and moral hazard. Most analyses of the crisis take it for granted by now that deregulation and lack of adequate oversight provided the conditions, indeed acted as incentive, from the 1980s for speculative feral capitalism to invent the financial instruments that enabled the players on the market to wager unbelievable amounts of other peoples money and make colossal profits. In The Big Short (2010), and in his earlier Liars Poker, Michael Lewis gives a spicy account of the obsessive drive to invent these new entities, a task entrusted to bright young things applying the mathematics of complexity and chaos, probability theory, risk analysis, sophisticated programming and informational technology, that had been deliberately harnessed to create the innovative financial products being traded. Gillian Tetts analysis in Fools Gold (combining her ethnographic expertise to her insider understanding of the financial world) underlines the formation of a selfenclosed culture amongst the key players in this trade that separated them from reality and fed unrestrained greed. One significant aspect which is highlighted by Lewis as well as Tett and Roubini and Mihm is that many of those involved in the trade did not understand these models and formulas that had been deliberately harnessed to create the innovative financial products being traded; indeed, Wall Street CEOs had only the vaguest idea of the complicated risks their bond traders were running (Lewis, 2010: xiv). It is a view shared by Tett who claims that most members of the banking and wider investing world had absolutely no idea how derivatives were producing such phenomenal sums, let alone what so-called swap groups actually did (2010: 4). Yet, these mechanisms are still in place and thus continue to shape the economic world and thinking about policy.

17 The way to obtain a striking picture of how the various elements worked to form a vicious cycle of leveraged accumulation that cumulated in the crash and secretes further crashes to come - is to examine the emergence and effects of the bonus system and its basis in the principle of shareholder value which has operated as the conduit or relay mechanism driving acceleration in the accumulation machine. The analysis will draw attention to two developments which in their combination have proved fatal. The first is the strategy of management to maximise shareholder value, and the second relates to the epidemic of moral hazard (Roubini and Mihm, 2010: 268), triggered by the effects of this corporate objective and the infernal machinery of leveraged debts, especially once free-market fundamentalism had freed the banking sector from restraining regulation. As we know, the bonus system has become institutionalised as a central feature of management practice across all business activities and has invaded many public sectors. In the absence of effective regulation, it remains endemic in the economy and public life today; an important consequence, as will become clear, is that it prioritises the interests of management, the firm and shareholders above all others; it is thus a development which reinforces Arendts view that an essential conflict separates public or common interest from private interest (section, 6). Ha-Joon Chang (2010) in 23 Things They Don't Tell You About Capitalism highlights the moves which have led to the bonus culture, principally, the principle of 'shareholder value maximization', advocated by management gurus, notably Jack Welch who is supposed to have come up with the term shareholder value in 1981, to align managers interest with the interest of owners or shareholders. Its purpose as a strategy was to 'incentivise' managers, in a business culture in which they had become the principal decision-makers in the wake of the professionalisation of management (a development J.K. Galbraith perceptively anticipated in The New Industrial State, 1967). The trick was to arrange a firms financial affairs to ensure it would be in managers interest to maximise the returns for shareholders. This was done by tying managers' reward to the amount they could give back to shareholders. The strategy consisted basically of three interconnecting elements: 1: Maximising profits by ruthlessly cutting costs to a minimum (through reduction in real wages, anti-union policy, cutting re-investments, etc). 2: Distributing the highest possible portion of profits to shareholders (this meant reducing investments in research and innovation, encouraging share buyouts, minimising reserves, etc). 3: Paying managers by adding stock options to their accounts or by increasing these options as part of their compensation (Chang, 2010: 17). The consequence of this strategy to ensure the coincidence of professional managers and shareholders interests has been to bypass the interest of other stakeholders such as workers and suppliers, who became the squeezed middle. As millions of workers and consumers have found out, the consequences of the shift towards privileging the short-term interest of managers and shareholders, and prioritising profit-maximisation, have been job cuts, the hiring of non-unionised labour after making everyone re-apply for their jobs, the outsourcing of as much as possible to low-wage countries like China and India,

18 the squeezing of suppliers like farmers - as many supermarkets do, for example -and pressurising governments to reduce corporate tax rates and provide subsidies to business with the help of the threat of relocating to countries with lower corporate tax rates and/or higher business subsidies. As a result, income inequalities soared ... and populations could share in the (apparent) prosperity only through borrowing at unprecedented rates (Chang, 2010: 18); these are precisely the borrowings which, as we saw, were recycled into the system through securitisation and the leveraging of debt from insecure loans into the gold of hyperprofit. It is not surprising to find that over the last decade or so the situation has encouraged companies to use an increasing part of their profits to buy back their own shares, both to boost the price of the shares on the market and thus increase the value of compensations, a practice boosted by fair value accounting practice (see Section 5 for the critique of accounting and auditing practices), and to gain a higher return than through savings. Corporations in the US used to invest 5% of profits in buyback, but the percentage climbed to 90% by 2007, which meant that little was left for reinvestment, or for development and other long term programmes (Chang, 2010: 19, 20). Short term strategies to maximise profit became institutionalised, acting as the ruling obsession. For instance, Chang says General Motors spent over 20 billion dollars on share buyback between 1986 and 2002, money it could have saved up and used when the crash hit them. The other fatal flaw in the bankrupcy of the economic system arises from the fact that the bonus system encouraged the propensity of firms and investors to take high risks because of the promise of massive returns, producing a crisis around the issue of 'moral hazard', as Roubini and Mihm explain: The bonus system, which focussed on short-term profits made over the course of the year, encouraged risk taking and excessive leverage on a massive scale (2010: 69). The connecting threads pass through the financial innovations described earlier, like collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), collateralised loan obligations (CLOs), credit default swaps (CDSs) and so on, soon extended to corporate loans and leveraged loans, which all became the securitised assets packaged, or laundered, and sold on to investors through special purpose vehicles or structured investment vehicles (SPVs and SIVs). It quickly became the established practice for lenders to originate and distribute these securities, since the mechanisms in place ensured that the risk was effectively transferred to investors all over the world, whilst banks no longer faced the consequences of bad loans (at least until the crash - though theres always a bailout round the corner) and could indulge in securitisation without due care and scrutiny (Roubini and Mihm, 2010: 33; 68-72). In the judgement of Roubini and Mihm, traders were greedy and arrogant and foolist too - but that alone would not have triggered the financial equivalent of a nuclear meltdown had the bonus system not become the dominant kind of compensation in the financial sector (op. cit: 32).

19 Furthermore, as the authors underline, ratings agencies were generous with their AAA ratings, since they benefited massively from the new financial operations, gradually deriving up to half of their profits from evaluating the new entities. The laxity of the ratings agencies together with the mind-boggling complexity of the securitised entities allowed originators to smuggle vast amount of bad debts into the financial system debts which have not disappeared. Moral hazard simply went out of the window, jettisoned because on the one hand, the apparatuses invented to make money through speculation, freed from regulatory checks, made possible unlimited accumulation, and, on the other hand, because the compensation system offered irreristible temptations for managers and speculators. The pickings were rich indeed, as many analysts have detailed - for example, Roubini and Mihm have noted that compensation for traders and bankers in the five major inventment banks in the USA was $25 billion in 2005, rising to $38 billion in 2007 (2010: 69). An important consequence of the extension of the bonus system to include quoted firms is that it institutionalised the values and attitudes of a management culture that saw the firm as primarily a vehicle for maximising profit on investment, which as noted, meant cutting costs to the bone at the expense of employees and suppliers (the squeezed middle), the quality of the products and service, reinvestments, longer-term planning and social responsibility. These are all well-known developments which corporations have pursued single-mindedly from the 1980s and the growing domination of the economy by neoliberal doctrines, whilst the ingredients of the bonus culture are still in operation today, providing accumulation for managers and shareholders at the expense of the public as a whole. The fact that, besides venture capitalists, the investors included insurance companies, pension funds, sovereign funds, local authorities, etc, whilst the assets included high risk or toxic sub-prime loans, credit card loans and other personal credits, means that we were all conscripted into the new financial system through our spending, borrowing and saving behaviour, as Lazzarato (2009) and Marazzi (2010) have shown. The point is that financialisation, the bonus system and its temptations, and moral hazard have become entwined, making it difficult to undo at the level either of the mechanisms involved or attitudes to money and the economy. The bonus system further illustrates the essential opposition between private interest and the public or common good (discussed in Section 6); its extension to the public domain schools, hospitals, universities, support services, etc and the management of public goods or commons fundamentally undermines and subverts the common interest. A salutary finding that challenges the assumptions and values support the universalising of the compensation or bonus system by the devotees of competition is that incentivising people through a reward or bonus scheme has often proved counter-productive, especially regarding tasks that require creativity or complex mental abilities as opposed to routine operations or simple physical tasks (N. Fleming, 2011, The bonus myth, New Scientist, 09.04.11). The reasons are complex, having to do with a range of parameters such as intrinsic as opposed to extrinsic motivation or satisfaction, playing safe to ensure

20 the reward, beneficiaries taking short-cuts to achieve the desired outcomes, added stress, and so on. A survey of the many studies show that the evidence used to support the idea of payment-for-performance, promoted by neocons and their individualist and cynical assumptions about the nature of human beings, is patchy at best and mostly weak (Serumaga in Fleming, op. cit: 43).

D. The end of capitalism? Or return to business as usual? A final remark about financial capitalism: commentators and the IMF have been warning for some months about the impending threat of another bubble which has been allowed to grow as a result of the unsurprising failure to reform the financial system, threatening another crash. It concerns the market in exchange traded funds (ETFs), centered on the commodities market, which is currently worth 1.2 trillion dollars (Inman, 2011, Guardian, 18.04.11: 21; Wachman, 2011). This new growth sector has all the features of the sub-prime mortgage and credit-driven bubble that burst in 2008: the securitisation of derivatives (packaging and reselling of securities, including, collaterised debt obligations (CDOs), with traders further down the line not actually owning the product but buying a share of future profits through the securities); the complexity of the products similar to credit default swaps; rapid, uneven, yet unregulated or poorly regulated growth in the financial sector, driven by entities which were the main factors in the crash, namely, hedge funds, equities, shadow banking (i.e. trading outside recognised exchanges) and off balance-sheet vehicles or special purpose vehicles (SPVs), which were invented to avoid regulatory oversight. Various parties have been forewarned, but basically, the market and its players, having fought off the restraining hand of regulatory bodies, cannot kick the habit of the derivatives-induced frenzy for hyperprofit: catastrophe has been institutionalised. So, nothing much has changed, whilst the price of commodities and arable land is already breaking records, and plans to tackle the environmental and ecological crisis and the threat of climate change have been diluted or put on hold. Amongst recent developments, we know that the land grab is growing apace, as a recent Oxfam Report details, highlighting the fact that since 2001, 227 m hectares have been sold or leased worldwide, half of it being in Africa (J. Vidal, Guardian, 22.09. 2011); it is known that even institutions like universities are using endowment funds to acquire arable land (J. Vidal, C. Provost, Guardian, 09.06.2011), and other reports have pointed out that British firms are leading the rush to buy up land for biofuels (Guardian, June 01, 2011). The same asset grab has been evident regarding minerals throughout Africa and other developing countries. For example, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, publicly owned mines have been sold off for a fraction of their value to offshore shell companies registered in the British Virgin Islands; they were then sold on to transnational corporations at a massive mark-up (Daniel Howden, The Independent, 23.11.2011: 31). Yet, the IMF approved loans of $551m to the DRC in 2009 on condition of improving transparency, and Western aid to the

21 country accounts for half of its budget (op cit). The reality is that corporate strategies and existing global infrastructures overdetermine such practices of asset enclosures, bound up with widespread corruption and profiteering. Such enormous transfers of wealth globally will continue until fundamental structural changes take place. To add to this picture of the real global economy, one could include the fact that the major food corporations the ABCD group: ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Dreyfus, which control between 70 to 90 % of world trade in grain - and the big four companies in global seed sales (Mosanto, Dupont, Syngenta, Limagrain, accounting for 50% of the trade) use their market dominance to dictate terms of trade disadvantageous to developing economies (Felicity Lawrence, Guardian, 02.06.2011), and cash in on near-slavery working conditions in agriculture (Guy Adams, The Independent, 29.06.2011). Furthermore, one could point to the effects of commodity speculation, stimulated by poor regulation of the commodities market, on the rise in food prices leading to crisis in poorer parts of the world (Felicity Lawrence, Guardian, 03.06.2011). On the financial front, the USAs quantitative easing the US central bank/Federal Reserves massive bank bond buying worth $600 bn instituted after the crash to tackle the deficit - has inflated financial markets, driving high inflation which has adversely affected many countries already struggling with the fall-out from the crash (Phillip Inman, Guardian, 30.06.2011). Related components of how contemporary capitalism is accumulating problems beyond the world of finance include the opening up of the Arctic for oil and mineral exploration, with possible catastrophic effects for the ecology of the region (Terry Macalister, The Guardian, 05.07.2011). The analysis of the ingredients which constitute the financial system and the demonstration of the impending disasters it secretes make clear that many players working the system knew what was happening and what the risks were, yet they carried on milking it for everything on offer and show little inclination to stop. Who then should be held accountable for the crises? The apparatuses put in place? The top management of banks and financial institutions? Investors and speculators? The deregulators and their neoliberal advocates? Politicians and their advisers who either do not fully grasp what is going on, or are fixated on orthodox doctrine and narrow short-term political gain? For Stiglitz (2010), as we saw, the fact that the key workings of the system have been the result of careful planning (a view supported also by the descriptions in Lewis, 2010 and Tett, 2010) points to underlying faultlines which must be addressed, though as I have argued, one needs to add the new informational technologies as one element of the machinery of dispossession enabling virtual money to make real money, or the M-M cycle again, now operating as a new form of rent, i.e. bypassing the production and circulation of material goods. Of course the whole history of inequality shows that someone down the line has to pay for the enrichment of the 1%, and we know who it is. Equally, the calculated manner of the whole machinery obliges us to recognise the central role played by the capitalist system of accumulation driven by the need for growth, and secured through the power relations inscribed in and

22 reproduced through it. This power has been evident recently in the success of global financial vested interests in forestalling the changes to the rules of the game proposed by many governments and regulatory bodies, in spite of the widespread recognition of some of the more obvious risky practices, such as allowing commercial banks to operate as investment banks using peoples savings to bet in casino capitalism. One may wonder how, short of conspiracy, a small number of people or corporations could exert such enormous power over governments and NGOs. Part of the answer lies in the fact that over the last fifty years or so neoliberal doctrine has successfully established itself as orthodox reason amongst decisions makers (Glynn, 2006; the story of this implantation is worth detailing, as Mirowski and Plehwe, 2009, have done in thier study The Road from Mont Pelerin; see also Harvey, 2005, Peck 2010). The other part relates to the systemic way the networks and systems of communication put in place to connect transnational companies work toward concentrating power in a small elite, in a sense independently of personalities and their interest, though clearly the convergence of the interest of players in the global economy is a factor too, bearing in mind the influence wielded through lobbies, or via the funding of political parties by corporations and the super-rich, and the management of dissent through the ownership of media by transnational corporations whose interests coincide with those of the dominant elite. A recent study of financial power by researchers at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology shows how this structurally embedded form of power works in practice when they analysed the degree of connectivity amongst networks of transnational companies. The findings reveal a web of ownership linking the largest transnational corporations (TNCs) whereby a super-entity of highly connected corporations formed through interlocking ownerships involving just 147 of them controls 40% of the entire network of 43,060 TNCs. Most of this tightly knit entity were financial institutions, and the connection includes share ownership in each other. The map of power also uncovers a wider set consisting of a core group of 1318 companies which controlled 60% of global revenues (Coghlan and Mackenzie, 22.10.2011, New Scientist, no 2835: 9). This concentration is both the result of preferential connectiveness motivated by existing power relations (players gravitate towards the most powerful groups, networks or individuals), and naturally occurring structures relating to systems characterised by complexity. So, the architecture of the network of power, the kind of business companies do and the shared assumptions about the economy combine to establish the super-entity determining the fate of the global economy. It means a small elite the 1%? - wields enormous power which can by-pass democratic control and regulations. It means too that appeal to individuals or groups to behave cannot work: only structural changes can alter behaviours and the way the system operates. As a coda to the story of the financial crash, one should note that the worlds richest individuals are now even wealthier after a slight dip in 2008 and 2009 though this situation is subject to stock market behaviour (Jill Treanor, Guardian, 23.06.2011, on the report by Merrill Lynch and Capgemini).

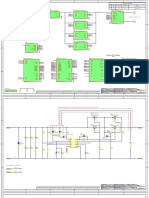

23 In the light of the wider global crises discussed at the start of the wider project establishing the entanglement of economic, environmental, resource and biodiversity crises, it is important to point out that all this is happening at a time when the gathering weight of evidence has increased the degree of confidence in the link between climate change and extreme weather (Steve Connor reporting on a world meteorological study by scientists at the British Met Office, the US National Center for Atmospheric Research, and the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, The Independent, 01.07.2011; issues of environment and climate change are discussed in Section 3). Additionally, findings by the Berkeley Earth Project, set up to double-check the claims made by supporters of the IPCC reports on climate change, and including climate skeptics amongst its members, confirm earlier conclusions and prognostics: the Earth is indeed heating up, as the graph below demonstrates (even if deniers dont want to see the obvious) (reproduced from the BBC Online News, 21.10.2011)

There is growing evidence too of possible mass extinction of oceanic species due to anthropogenic pollutants and activity, (M. McCarthys report of findings by the International Programme on the State of the Ocean and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, The Independent, 21.06.2011). It is clear that the endemic crises I examined in earlier sections (Section 1 & 3) have, if anything, worsened rather than improved, as the financial turbulences of August 2011 show. Against this sense of deepening problems, one must

24 recognise widespread, spontaneous and collectively organised discontent and loss of faith in the gods that have failed (Elliott and Atkinson, 2008), appearing in events as diverse as the Arab Spring of 2011 and the Occupy movements mass demonstrations across the world against the austerity measures which have hit the general public and spared those whose actions created the problems.

E.

Options for the future.

So, what are the current options for dealing with the on-going economic crisis, seen by the dominant orthodoxy, or at least publicly presented by its adherents, as centered on state deficit or sovereign debt and financial instability? The conventional approach for rebalancing the economy and reducing state deficit in the short to medium term has been to make the general public pay through a double transfer of wealth to try and stabilise the global economy whilst protecting the gains already made by the super-rich. The policies being pursued are consistent with the neoliberal worldview and its version of the economy, packaged into a combination of schemes aimed at squeezing a greater proportion of wealth from the majority of citizens: taxation rebanding, lowering real wages, quantitative easing, the reduction or elimination of benefits, the selling off of common or social wealth, and the privatisation of public services to generate new sources of profit for corporations. It is clear that such measures enable the winners once more to not only escape having to share the burden but extend their hold on the economy. The problems associated with this approach are well-known and have been examined throughout the wider work: pauperisation, increasing inequality, decreases in equal opportunity for the younger generation in particular, massive unemployment, reductions in productive capacity (firms operating at below capacity), lower state revenue because of unemployment and lower levels of production and sale, costs arising from health issues and the need for the state to provide at least a vital minimum, inflation or stagflation, lower quality services, the worsening of support services and decreases in common-pool resources like libraries and subsidised transport, costs arising from increases in crime and so on; they all reduce the quality of life of citizens whilst increasing insecurity at all levels. Meanwhile, little will be done to address growing environmental, ecological and resource crises, as the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Durban in December 2011 shows, since delegates could only agree on a promise to do something in the future, that is, when the time is right. Other short-term options appear to be mostly incoherent and hybrid schemes that pragmatically allow the purist free market policies of regulation to be bolted onto a state intervention component, such as investments in infrastructure and a number of technologies concerning technological innovation, the support for grapheme in the UK is one of the more sensible policies, whilst green and sustainability schemes are backed by state funding in many other countries.