Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Sustainable Development - A Rediscovery of The Past

Enviado por

Michel CamesTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Sustainable Development - A Rediscovery of The Past

Enviado por

Michel CamesDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Michel CAMES MA in Development Studies Core Course - Issues in Development Experience University of Leeds Essay - Semester 2 1995/96

Sustainable Development, a rediscovery of the past? In what follows, I shall aim to discuss a major cause of ecological unsustainability at the local level in developing countries and how rekindling social sustainability by reducing vulnerability can play an important role in the process of diminishing environmental degradation. I attempt to show how historically unsustainability has emerged and will confront the present focus on strengthening community-based resource management systems to precapitalist traditional practices in order to make the point that sustainable development is not so much an invention of the future as a rediscovery of the past (Redclift, 1987:171). To make this clear, I will first elucidate the links between poverty and environmental degradation to highlight the problem of sustainability for the poor in developing countries. I will proceed by shedding light on the gradual infiltration of the pre-colonial village economy with commoditized production relations with reference to India pointing to the gradual loss of social and ecological sustainability. Next I will discuss the present renewed interest in the collective management of resources as a way out towards life styles which touch the earth lightly (Chambers et al., 1992:6) which remind us of a natural economy which has been ruling ever since until capitalism set out to conquer the world and with it the commoditization of resources. My attempt to define the constraints of a more collective management approach will conclude this essay.

The problem: Vulnerability Over-population and ignorance are frequently cited as being responsible for resource depletion in developing countries. Consequently there has been a wide range of discourse focusing on population control and how peasants in developing countries had to be taught or motivated to adopt more environmentally sustainable practices. Western social, political and economic engineering was expected to lead out of the dilemma. With increasing experience and respect for local skills and needs however, Western social scientists gradually recognized that local peasants have been using sustainable practices for centuries in locally-adapted ways. They realized that it was vulnerability and not poverty as such which let certain peasants, or as Broad defined them, the very, very poor - the landless and rootless sub-subsistence peasants and squatters (Broad, 1994:813) proceed in environmentally unsustainable ways even against their better judgement. The lack of meeting basic needs often forces these poor to be shortsighted in their daily management of the environment in order to survive. Hildyard argues in regard of deforestation that making scapegoats of the poor and dispossessed not only obscures the reason for their poverty but detracts from the real causes, viz. massive commercial development schemes and government-sponsored colonization schemes (Lele, 1991:617, quoting Hildyard, 1987). According to Swift, vulnerability is not simply another word for poverty. Poor people are usually among the most vulnerable, but understanding vulnerability means disaggregating poverty. He defines a set of failures which are affecting vulnerability. Whereas production failures like drought, flood, animal and plant disease act directly, exchange failures interact through the markets for wage labour and commodities. Himself basing on Sen (1981), he claims that while in South Asia agricultural labourers and

people in small scale service trades are particularly vulnerable because of the sensitivity of their wage rates to changes in the wider economy, in Africa it would be the pastoral economies which are most vulnerable to terms of trade failures (Swift, 1989:8-9). Chambers et al. expand Swifts discourse to include normal living as well as survival in crisis. They distinguish between tangible assets - stores and resources commanded by a household - and intangible assets, which consist of claims made in times of stress or shock and access the opportunity in practice to use a resource (Chambers et al., 1992:9-11). Vulnerability is increasingly caused by a lack of intangible assets. The state of the local civil society formerly based on kinship relations has been transformed towards more individualistic relationships based on the western philosophy. As Swift argues: The growth of commodity production and market relations (...) has undermined the redistributive guarantees of the pre-colonial economy, replacing them with an uncertain market mechanism. As modern government has taken over the powers of traditional political authorities, it has (...) imposed a substantial tax burden, offering in theory in return some social security in the most general sense (Swift, 1989:12). Redclift et al. identify the lack of access as a major cause of environmental degradation linked to the vulnerability of the poor: Biological resources are often under threat because the responsibility for their management has been taken away from local people and transferred to distant government agencies. The rural people who live closest to valuable environmental resources, such as tropical forests and wetlands, are often those who are most economically disadvantaged and have least stake in their exploitation. Excluded from management of their local environment local people cease to act like stewards and become poachers (Redclift et al., 1994:11).

As Broad argues, people who have lived in an area for some time or have developed some sense of permanence are unlikely to degrade it as it would mean they would degrade their own livelihood. Thus corporations with no roots - or distant government departments - are likely to be insensitive to the environmental consequences of their actions (Broad, 1994:819). The same could be said for rootless people. With the on-going breakdown of traditional societies more and more people are cast out of such linkages and are prone to lose in this process their links to their area of residence. Often enough this leads to a survival strategy with the adoption of an opportunistic way of life. Inversely, vulnerability is enhanced if environmental degradation is threatening the natural resource base of which the poor live. Many peasants who have been able to meet their needs so far are experiencing deteriorating living standards due to environmental externalities of commercial activities. An insight into the consequences of the application of pesticides in the Philippines makes this clear: Previously, the farmer easily provided for his meals by catching fish in the rice field (...). But not anymore. Fish in the ricefields are disappearing. So are snails, oysters, crabs, shrimps, frogs and other aquatic creatures (Bull, 1982:65 quoting Punla Foundation Inc., 1981). Let us now turn towards the past and explore how vulnerability has been affected over time. The past: Destruction of the natural economy Taking as an example the transformation of the Indian pre-colonial village society, I want to show how monetization and commoditization introduced by the British paired with a steady drain of surplus gradually undermined the livelihoods of the villagers. This is not a plea for a pre-colonial merry

India in which everyone shared and there was no famine. Swift argues that the risk-avoidance strategies of pre-capitalist rural societies extended beyond agricultural and pastoral techniques into social and political mechanisms which included more formalized expectations about the role of patrons or elite classes in ensuring peasant subsistence needs in a crisis (Swift, 1989:12). According to Alavi, the rural pre-colonial Indian society was self-sufficient despite the urban society drawing on its economic surplus. He continues: Village artisans and a variety of village servants provided goods and services that were needed by members of the village community and they were in turn maintained by the village community by payment of ritually fixed shares of every peasants crop that had to be rendered at every harvest. In return the cultivator and his family were entitled to receive from the village servants their services or goods on the basis of accepted standards of their needs (Alavi, 1989:6). The situation changed under colonial rule. The goal of the British was to introduce private property which could easily be taxed. This was achieved by forming a more uniform landlord class with a marked reduction of any possible entitlements of lower classes. According to Fuller, the granting of private property rights in land destroyed the structure of the distributive system (Fuller, 1989:34). As Bagchi contends, the British having altered the whole system of revenue assessment, they affected fundamental changes in the production relations. Whereas the Mughals had assessed land revenue on the area actually cultivated, the British assessed this revenue on the basis of the amount of land a person was entitled to cultivate (Bagchi, 1982:83). Thus a bad harvest would not mean a reduction in tax. This also had to be paid from then on in cash which made the peasant dependent on the vagaries of a market.

Gadgil et al. point to the fact that large areas of forest were taken over by the colonial state. This constituted a social watershed - by curbing local access it radically altered traditional patterns of resource use - and an ecological watershed, in so that the emergence of timber as an important commodity fundamentally altered forest ecology. They argue that for a long time, the takeover of the forest was bitterly resisted by local populations for whom it represented an unacceptable infringement of their traditional rights of access and use (Gadgil et al., 1994:104-105). The forceful introduction of natural economies into the capitalist mode of production was necessary for industrializing countries as, according to Luxemburg, a purely internal accumulation of capital was impossible (Bradby, 1975:128 quoting Luxemburg, 1951:1972). This process of the destruction of the natural economy was completed according to Bradby when land and labour power become commodities and the end of production came to be the creation of surplus-value for capital (Bradby, 1975:128). The transformation was mostly very gradual. As Wolf depicts it, mercantile activity and accumulation remained significant in many world regions not directly engulfed by machine production. In these areas advancing merchants created commodity frontiers and labour frontiers. (...) ... initial mercantile penetration often enabled groups to continue in the kinordered or tributary mode ... (...) Increasing exchange however, gradually undermined the autonomy of the local group. (...) ... as the sphere of exchange widened, the native producers tended to become clients of the trader rather than symmetrical partners ... (...) (Thus) they came to depend increasingly on the wider capitalist market. They confronted a gradual reduction in their ability to control their means of production, especially as widening exchange eroded their ability to reproduce these means through the mechanisms of kinship or power. Similarly, tributary elites, drawn into dependence on goods produced under capitalist

auspices, found themselves under pressure to intensify tributary labour and to redirect it toward commercial production (Wolf, 1982:306-307). With the gradual transformation of the village economy, the vulnerability of the poorer grew. Kinship links gradually weakened and the common provision of goods and services gave way to the need to purchase these with cash. Self-sufficiency was substituted by market relations being ruled by metropolitan or urban interests. Ironically, in the postcolonial period this process only accelerated. Bound to the world economy, most ex-colonial nations - or their elites formed under colonial auspices - desperately seeked to break free from a conceived backwardness and consequently intensified the process of commercialization implying further marginalization of the poor. A reappraisal of traditional management Despite the inability or unwillingness of multilateral organizations to dissociate from the concept of growth and a technological approach to the alleviation of poverty, it has become increasingly clear among social scientists that a way out of the dichotomy of environmental degradation and poverty can only be found in a more soft approach which increases the social sustainability of the poor. Or, as Redclift puts it: Rational environmental management makes the world safe for development, however, it does not make the environment safe for the poor and their livelihoods (Redclift, 1987:172). We must consequently ask what does make the environment safe for the livelihoods of the poor and how we can achieve this. Among Chambers et al.s policy implications for the poor not to become poorer, reducing vulnerability by restraining external stress, minimizing

shocks, providing safety nets and giving priority to the capabilities, assets and access of the poorer is advocated (Chambers et al., 1992:32). According to Redclift et al., among the most appropriate measures for effecting this change is the assignment of management responsibilities to local institutions, strengthening community-based resource management systems, and introducing a variety of property rights and land tenure arrangements (...). These approaches can serve to rekindle traditional resource management practices, and focus the attention of the local community on the value of indigenous knowledge and experience. This case is strengthened where natural environments are particularly rich - for example in biodiversity. People living in and around the forests, wetlands and coastal zones often exercise more power than governments in the use that is made of biological resources; but the conservation of these resources is rarely linked with more sustainable livelihoods (Redclift et al., 1994:11). On the issue of conservation in India, Kothari et al. argue further about the hypocritical nature of government policies with regard to wildlife habitats: local forest-dwelling communities are denied their traditional rights and access to forest resources in the name of wildlife conservation, while the same areas are being opened up to commercial uses and elite tourism. The need for clearer and more flexible legislation concerning peoples rights and permitted activities in each different protected area (...) is thus of paramount importance, as is a mandate to involve local communities in planning and managing protected areas (Kothari et al., 1995:192). Tisdell asserts that there is evidence that some common-property resources can provide a highly productive and equitable use of land even in settled agricultural communities if they are collectively managed (Tisdell, 1988:381).

In some places local management systems are still intact. In India for example, according to Hausler, functioning communal management systems provide security of tenure to the user group, use regulations which are evolved locally, and marked by simplicity of individual rules and an ability to change these rules to meet new challenges; benefit allocation managed by the community to reflect the realities of the community structure (Hausler, 1993:86 with reference to Arnold et al., 1989). However, where new management systems have to be created, major hurdles arise. As Hausler points out in the case of forest management in Nepal, management plans were often written up by forest rangers to reflect their own perception of local needs and then merely presented for endorsement to the committees, which were often dominated by local political leaders. Many forest committees which were formed in such a top-down fashion were therefore inactive (Hausler, 1993:88-89). Kothari et al. argue that other quick fixes may also backfire. Putting women on hastily-convened village forest committees may actually marginalize them. (...) In a public arena they are likely to have been taught to be silent, whereas in other arenas they may have more of an existing power base on which to build further struggle for more community influence. Similarly, hiring local forest guards may undercut local traditions of labour exchange and makes guards less accountable to locals and more susceptible to bribes (Kothari et al., 1995:193). But this should not be surprising. Integrating socio-economic matters into a pursuit for ecological sustainability cannot be expected to go off smoothly. Local management systems have often evolved over centuries to find the equilibrium exactly adapted to local environmental conditions and the interplay of political forces.

As Redclift et al. put it, the articulation of demands by local groups (...) inevitably means the exercise of power, and resistance to it. (...) Conflicts over the management of environmental resources (...) help to bring new social relationships into being (...) through which existing relations are democratized or opened up (Redclift et al., 1994:13). This cannot be achieved with a quick fix mentality. Given the potential of gain however, ecological, economic and social, of a much greater involvement of local communities in environmental management decisions, the re-establishment of common resource management is meant to be a long-term goal of sustainable development. Implications It is being gradually recognized that strengthening community-based resource management systems can have a tangible impact on the alleviation of poverty for the one billion people living unsustainably at or below subsistence levels (Broad, 1994:813 with reference to Durning, 1992); whether it will, is a matter of guesswork. However, some conditions can be identified which make this approach more likely to succeed. First, we should not have a misconception of reinstating a situation of a lost paradise. As case studies already show, devolution of governance does not necessarily imply the reinstatement of a more equitable distribution of power. We might have to accept that there is a possible trade-off between less equity in the short run with more ecological sustainability in the long run (Woodhouse, 1996). We must internalize that setbacks will occur and it is just this resistance from the more powerful which indicates us the scope of the change. We should also be aware that this process is not an end in itself, and as Foucault argued: Every strategy of confrontation dreams of becoming a

10

relationship of power, of finding a stable mechanism to replace the free play of antagonistic forces (Redclift et al., 1994:13 quoting Foucault, source n. i.). Then, we must question populist tendencies attempting to minimize the manifold hurdles piling up in front of a true participatory and democratic formation of community-based management committees. A good deal of questioning and willingness to cooperate with people and new ideas will be of importance to set in motion this process. More, as Redclift argues, if we want to know how ecological practices can be designed which are compatible with social systems, we need to embrace the epistemologies of indigenous people, including their ways of organizing their knowledge of their environment (Redclift, 1987:151). We must question the ubiquitousness of Western science (Redclift, 1991:41), leave room for non-knowledge (Redclift, 1991:41 quoting Capra, 1988) without on the other hand simply reversing hierarchies of Western knowledge over local, vernacular knowledges (Hausler, 1993:89-90). If we consider these principles, we will not be bewitched by discovering elements from the past, however we might be on the verge towards creating more sustainable livelihoods, which, according to the criteria of Chambers et al. (1992:26) were abundant not at this point of history, but, to a much greater extent, in the past.

11

Bibliography Alavi, Hamza, Formation of the Social Structure of South Asia under the Impact of Colonialism in Alavi, Hamza and Harriss, John (1989), Sociology of Developing Societies South Asia, Houndmills, Basingstoke and London, MacMillan Ltd. Arnold, J. E. M. and Steward, J., cited in Arnold, J. E. M. (1989), Community Forestry: Ten Years in Review, Rome, FAO Bagchi, Amiya Kumar (1982), The Political Economy of Underdevelopment, Reprinted 1993, Cambridge, University of Cambridge Bradby, Barbara, The destruction of natural economy in Economy and Society, 4, 1975 Broad, Robin, The Poor and the Environment: Friends or Foes? in World Development, 22 (6), pp. 811-822, 1994 Bull, David (1982), A Growing Problem - Pesticides and the Third World Poor, Oxford, Oxfam Capra, F. (1988), Uncommon Wisdom, London, Fontana Chambers, Robert and Conway, Gordon R. (1992), Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for the 21st Century, Sussex, IDS, Discussion Paper 296 Durning, Alan (1992), How much is enough?, New York, W. W. Norton for Worldwatch Institute Fuller, Chris, British India or Traditional India?: Land, Caste and Power in Alavi, Hamza and Harriss, John (1989), Sociology of Developing Societies South Asia, Houndmills, Basingstoke and London, MacMillan Ltd. Gadgil, Madhav and Guha, Ramachandra, Ecological Conflicts and the Environmental Movement in India in Ghai, Dharam (1994), Development and Environment - Sustaining People and Nature, Oxford, Blackwell Hausler, Sabine, Community Forestry: A Critical Assessment - The Case of Nepal in The Ecologist, 23 (3), 1993 Hildyard, N., Tropical Forest: A plan for action in The Ecologist, 17 (4/5), 1987 Kothari, Ashish, Suri, Saloni and Singh, Neena, People and Protected Areas - Rethinking Conservation in India in The Ecologist, 25 (5), 1995 Lele, Sharachchandra M., Sustainable Development: A Critical Review in World Development, 19 (6), pp. 607-621, 1991

12

Luxemburg, Rosa (1951), The Accumulation of Capital, London, Routledge Punla Foundation Inc., Quezon City, Philippines, Rural Poverty Series, January 1981 Redclift, Michael (1987), Sustainable Development - Exploring the contradictions, Reprinted 1991, London, Routledge Redclift, Michael (1991), The Multiple Dimension of Sustainable Development in Geography, Course Handout in Core Course Redclift, Michael and Sage, Colin, Introduction in Redclift, Michael and Sage, Colin (1994), Strategies for Sustainable Development Local Agendas for the Southern Hemisphere, Chichester, Jon Wiley & Sons Ltd. Swift, Jeremy, Why are Rural People Vulnerable to Famine? in IDS Bulletin, 20 (2), 1989 Tisdell, Clem, Sustainable Development: Differing Perspectives of Ecologists and Economists, and Relevance to LDCs in World Development, 16 (3), pp. 373-384, 1988 Wolf, Eric R. (1982), Europe and the People Without History, Berkeley, University of California Press Woodhouse, Philip, University of Manchester, Seminar held on 24 April, 1996 at CDS, University of Leeds, on Local Governance and Rural Resource Use in Sub-Saharan Africa

13

Você também pode gostar

- Critical Evaluation of The European Diesel Car Boom - Global Comparison, Environmental Effects and Various National StrategiesDocumento22 páginasCritical Evaluation of The European Diesel Car Boom - Global Comparison, Environmental Effects and Various National StrategiesMichel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- The Viability of The Peasant EconomyDocumento16 páginasThe Viability of The Peasant EconomyMichel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- Biogas and The Rural PoorDocumento17 páginasBiogas and The Rural PoorMichel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- Managing Market-Based DebtDocumento13 páginasManaging Market-Based DebtMichel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- Cooperating in The CommonsDocumento17 páginasCooperating in The CommonsMichel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- Linking Development and Poverty Alleviation in IndiaDocumento45 páginasLinking Development and Poverty Alleviation in IndiaMichel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- Lux Social Model - Quo Vadis - Cames-2011Documento69 páginasLux Social Model - Quo Vadis - Cames-2011Michel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- Luxembourg Earnings From Fuel Tourism - TE-2011Documento5 páginasLuxembourg Earnings From Fuel Tourism - TE-2011Michel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- Corporatist Governance in Luxembourg - Cames-2010Documento25 páginasCorporatist Governance in Luxembourg - Cames-2010Michel CamesAinda não há avaliações

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (119)

- Group - 8 OtislineDocumento2 páginasGroup - 8 OtislinevAinda não há avaliações

- Report Anomalies and Normalization SummaryDocumento5 páginasReport Anomalies and Normalization SummaryThomas_GodricAinda não há avaliações

- Copyright Protection for TV Show FormatsDocumento11 páginasCopyright Protection for TV Show FormatsJoy Navaja DominguezAinda não há avaliações

- Sims 4 CheatsDocumento29 páginasSims 4 CheatsAnca PoștariucAinda não há avaliações

- Data Acquisition Systems Communicate With Microprocessors Over 4 WiresDocumento2 páginasData Acquisition Systems Communicate With Microprocessors Over 4 WiresAnonymous Y6EW7E1Gb3Ainda não há avaliações

- LP Direct & Indirect SpeechDocumento7 páginasLP Direct & Indirect SpeechJoana JoaquinAinda não há avaliações

- Baptism in The Holy SpiritDocumento65 páginasBaptism in The Holy SpiritMICHAEL OMONDIAinda não há avaliações

- 471-3 - 35 CentsDocumento6 páginas471-3 - 35 Centsashok9705030066100% (1)

- Assignment On Diesel Engine OverhaulingDocumento19 páginasAssignment On Diesel Engine OverhaulingRuwan Susantha100% (3)

- 1.MIL 1. Introduction To MIL Part 2 Characteristics of Information Literate Individual and Importance of MILDocumento24 páginas1.MIL 1. Introduction To MIL Part 2 Characteristics of Information Literate Individual and Importance of MILBernadette MendozaAinda não há avaliações

- 20764C ENU Companion PDFDocumento192 páginas20764C ENU Companion PDFAllan InurretaAinda não há avaliações

- A Legacy of Female Autonomy During The Crusades: Queen Melisende of Jerusalem by Danielle MikaelianDocumento25 páginasA Legacy of Female Autonomy During The Crusades: Queen Melisende of Jerusalem by Danielle MikaelianDanielle MikaelianAinda não há avaliações

- Grade 5 DLL SCIENCE 5 Q4 Week 9Documento6 páginasGrade 5 DLL SCIENCE 5 Q4 Week 9Joanna Marie Cruz FelipeAinda não há avaliações

- Edith Bonomi CV SummaryDocumento1 páginaEdith Bonomi CV SummaryEdithAinda não há avaliações

- Differential and Integral Calculus FormulasDocumento33 páginasDifferential and Integral Calculus FormulasKim Howard CastilloAinda não há avaliações

- Violent Extremism in South AfricaDocumento20 páginasViolent Extremism in South AfricaMulidsahayaAinda não há avaliações

- Exercise 1: Present ProgressiveDocumento3 páginasExercise 1: Present ProgressiveCarlos Iván Gonzalez Cuellar100% (1)

- 01 Petrolo 224252Documento7 páginas01 Petrolo 224252ffontanesiAinda não há avaliações

- A Photograph Poem Summary in EnglishDocumento6 páginasA Photograph Poem Summary in Englishpappu kalaAinda não há avaliações

- Pilar Fradin ResumeDocumento3 páginasPilar Fradin Resumeapi-307965130Ainda não há avaliações

- 일반동사 부정문 PDFDocumento5 páginas일반동사 부정문 PDF엄태호Ainda não há avaliações

- RitesDocumento11 páginasRitesMadmen quillAinda não há avaliações

- Understanding Culture, Society, and Politics - IntroductionDocumento55 páginasUnderstanding Culture, Society, and Politics - IntroductionTeacher DennisAinda não há avaliações

- Legend of The Galactic Heroes, Volume 1 - DawnDocumento273 páginasLegend of The Galactic Heroes, Volume 1 - DawnJon100% (1)

- Somatic Symptom DisorderDocumento26 páginasSomatic Symptom DisorderGAYATHRI NARAYANAN100% (1)

- Advantage and Disadvantage Bode PlotDocumento2 páginasAdvantage and Disadvantage Bode PlotJohan Sulaiman33% (3)

- STS Gene TherapyDocumento12 páginasSTS Gene Therapyedgar malupengAinda não há avaliações

- Exery Analysis of Vapour Compression Refrigeration SystemDocumento22 páginasExery Analysis of Vapour Compression Refrigeration Systemthprasads8356Ainda não há avaliações

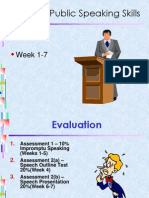

- TOPIC 1 - Public Speaking SkillsDocumento72 páginasTOPIC 1 - Public Speaking SkillsAyan AkupAinda não há avaliações

- Resume VVNDocumento1 páginaResume VVNapi-513466567Ainda não há avaliações