Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

Monetary Instruments in The Philippines: Focus On Open Market Operations

Enviado por

Apple CruzDescrição original:

Título original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Monetary Instruments in The Philippines: Focus On Open Market Operations

Enviado por

Apple CruzDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Number Thirty,

Volume XVII,

No. 1,1990

MONETARY INSTRUMENTS AND THE CONTROL LIQUIDITY IN THE PHILIPPINES: FOCUS ON OPEN MARKET OPERATIONS Armida Introduction Monetary S. San Jose

OF

policy refers to actions .of the.. Central Bank (CB)

or monetary authorities which are (1): aimed at".helping achieve macroeconomic goals, and (2) exercised by infiuenc_ng such financial factors as the quantity of money and the level of interest rates. Monetary policy shares the general goals of macroeconomic stabilization policy such as price stability, economic growth and balance of payments equilibrium or exchange rate stability. In addition, monetary policy has some more specialized goals such as interest rate stability and a strengthening of the financial system. In a monetary economy, an excess supply of liquidity opposed by an excess demand for goods and services could result in rising prices and/or a deterioration in the balance of payments. On the other hand, an insufficient supply of money could hamper economic growth and development. The task of monetary policy therefore is to keep the supply of money growing at an appropriate rate to ensure sufficient economic growth and to maintain internal and external stability. For the CB to achieve the goals of monetary policy, it must be able to operate through variables which are directly under its control, called instruments, since goals are not directly controllable. Thus, monetary policy actions must be made by means of instruments. Moreover, since a change in an instrument may not affect a variable which is an ultimate goal of monetary policy, intermediate variables which are referred to as intermediate targets are identified. These intermediate targets serve as the channel through which monetary instruments act on the economy in order to attain the desired goals. Intermediate variables must be relatively controlled by the CB, and their effects on the final objective should be reasonably predictable. In the case of the Philippines, money supply is the intermediate

Acting Associate Director, Department of Economic Research (Domestic), Central Bank of the Philippines, Prepared for the SEACEN Seminar on Open Market Operations as a Monetary Instrument, July 19-21, 1988, Manila,

134

JOURNAL

OF PHI LIPPINE DEVELOPMENT

target of monetary policy. Meanwhile, monetary policy instruments include open market operations, the rediscount window, reserve requirement, etc. The outline of this paper is as follows. Section I discussesthe framework for analyzing how monetary instruments affect monetary targets. Section II describes the various instruments available to the Central Bank of the Philippines as well as their advantages and disadvantages. The last section summarizes the factors and conditions that are considered in the choice of instruments and why open market operations are preferred over other instruments. I. The Control of Domestic Liquidity For purposes of this presentation, the supply of money is defined as the currency in circulation or the currency held by the nonbank public (C) plus deposit liabilities of commercial banks (D) which include demand deposits (rid), savings(sd) and time deposits (td), and deposit substitutes(ds). In the Philippines, this definition of money is called M3 or domestic liquidity. Thus, M3 = C+D whereD = dd + sd + td + cls

(1)

Reserve money (RM) comprisesC and reservesof commercial banks (R) which include cash in banks' vault and reservebalances or deposits of commercial banks with CB. In the Philippines,however, commercial banks' holdings of certain reserveeligible government securities (REGS) 1 are considered as reserves. Thus, base money (BM) may be differentiated from RM asgiven by the followingequation: RM =C+R BM or

TM

C + R + REGS

(2)

(3)

BM = RM + REGS

The money multiplier (k) is defined as the ratio between M3 and RM. Thus, from equation (1)and (2) k C+D C+R (4)

SAN JOSE: MONETARY

INSTRUMENTS

AND LIQUIDITY

135

The supply of liquidity can be expressed as the product of the money multiplier and RM. M3 = kRM (5)

Equation 5 showsthat the supply of liquidity isaffected by changes in the stock of RM and in the money multiplier. Changes RM and in the money multiplier are in turn effected through the useof monetary policy instruments such as open market operations, reserve requirement, rediscounting, etc. To clearly understand the process by which monetary instruments affect RM and k and eventually M3, the composition of k and RM could be examined. In the case of k as given by equation 4, each component of k may be divided by total deposits (D) on the assumptionthat these componentsare proportional to total deposits.Thus: C+D k = O D C+R D D c+1

c+r

(6)

(7)

where c = currency todeposit ratio r = required reserves againstdeposits Meanwhile, RM as defined in equation 2 represents the liabilities of the CB. However, CB controls its liabilities by controlling its assets.When viewed from the assetside, RM may be defined as the sum of its net foreign assets(NFA) and net domestic assets(NDA). Net domestic assets,on the other hand, are composed of net domestic credits to the public sector (NDC Pub.), net domestic credits to the private sector (NDC Pri.) and net other items (NO/). Thus; RM = NFA + NDA RM = NFA +NDC + NDC + NO/

pub pti

(8)

136

JOURNAL

OF PHI LIPPINE DEVELOPMENT

Substituting equations (7) and (9) in equation (5) gives M3 -- c+1

c+r

(NFA + NDC + NOC + NOI) pub pri

(10)

The right-hand side of equation 10 shows the determinants of M3. From this equation, it can be seen that a reduction in r which would cause k to increase would result in an increase in supply of banks' reserves available for lending and ultimately in an increase in the supply of M3. Monetary policy instruments can also affect M3 through changes in RM. For instance, when CB grants loans to banks (say in the for,m of rediscount credits), CB's NDC increases,and is

pri

accompanied by an increasein reservebalances of banks. The increase in reservebalances of banks in turn would enable banks to increase lendingsand thus generate depositsor liquidity equal to k times the initial increasein reserves. While equation (10) shows that the supply of M3 can be influenced by CB actions through the use of monetary instruments, it is also affected by factors which are not exactly within the control of CB. Insofar as components of CB's assetsare concerned, NFA is directly related to the balance of payments (BOP) position of the country. And since the BOP is affected by external factors such as economic growth in major trading partners, foreign inflation rate, import and export prices, etc., NFA may be said to be not directly controllable. However, in the case of the Philippines, the BOP is one of the major objectives that get translated into a target for CB's NFA. In this case, the desired level of CB's NFA which is consistent with the BOP objective is determined and becomes a target variable. Meanwhile, CB's credit to the public sector may also be difficult to control, unless ceilings are imposed. In most lessdeveloped countries (LDCs), this variable is correspondingly adjusted to the government's budgetary requirement. In casesof a Philippine government stand-by arrangement with the International Monetary Fund (the Fund), a ceiling on CB credit to the public sector is imposed to instill fiscal discipline and to enhance the attainment of monetary goals. Moreover, the Philippine CB Charter also provides a statutory limit on the amount of borrowings that the National Government can obtain from CB for any given year which is equivalent to 20 percent of the National Government's average earnings (or revenues) for the past three years. Hence, to a certain extent, CB credit to the public sector can be predicted if not controlled. The major determinant of M3 as shown in equation 10 that can be directly controlled by CB is its credits to the private sector (or banks) which are in turn influenced through changes in the various instruments.

SAN JOSE: MONETARY

INSTRUMENTS

AND LIQUIDITY

137

Of the components of k, the currency ratio is determined by the general public's preference to hold either cash or deposits. While this decision to a certain extent may be influenced by CB through interest rates, e.g., higher interest rates may induce the public to minimize cash holdings and keep larger amounts of deposits, it is also affected by other uncontrollable factors, in the Philip_ pines, the currency ratio was found to be largely affected by noneconomic factors such as uncertaintiesover political and peace and order conditions. The controllable component of k, therefore, is r since it is the CB that determines and has authority to changethe reserveratio. Operationally, monetary control may be imprecise in that it is difficult for CB to maintain M3 at precisely the level it considers appropriate and desirable becauseof changesin the noncontrollable factors whose impact on M3 is not entirely predictable. The degree of precision of CB's control over M3 depends on how well it can predict not only movements in the uncontrollable factors but also their impact on monetary aggregates and, consequently, on the final objectives. If the uncontrollable factors do not behave as expected, changesor adjustmentsare made through policy instrumentsto offset the impact of such factors on the intermediate target M3 and on the final objectives. I1. Instrumentsof Monetary Policy in the Philippines

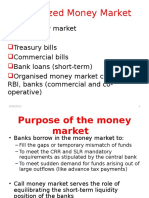

Monetary policy instruments in the Philippines may be classified into three types: (1) those that are used as market intervention controls in the financial markets to influence the availability and rate of return on assetssuch as open market operations and rediscounting; (2) those that placerestrictions on the portfolios or operations of banks suchas reserverequirement and direct controls; and (c) others that do not strictly fall into the first two types such as National Government (NG) deposits with CB from proceedsof Tbills sales, prior import deposits and moral suasion. These instruments of monetary policy are discussedbelow. A. Market Intervention Open market operations In the Philippines, open market operations consist of the following instruments: Repurchase Agreements (RPs) - Theseare transactionswherein the CB buys governmentsecuritiesfrom banks with a commitment

138

JOURNAL

OF PHI LIPPINE DEVELOPMENT

to sell them after a specified period for a certain consideratione.g., interest rate. RPs are undertaken only when the desiredeffects on the level of reservemoney are temporary. This is becauseRPs have short-term durations. In effect, RPsare interest-bearingloans given by the CB to banks on the basisof governmentsecuritiesas collateral. RPs may be categorized into two kinds: regularand overnight. Regular RPs are undertakings where the CB buys government securities from these dealers with a commitment to sell back the same securities at a stipulated interest rate and after a specified period. Regular RPsare undertaken by CB for a period not exceeding 15 days. The interest rate charged by CB is market-oriented, taking into account the prevailing interest rates for T-bills and interbank rates, among others. The governmentsecuritieswhich may be usedare those (a) issuedby the NG or its instruments; (b) unconditionally guaranteed by the NG; and (c) maturing within a period not exceeding 10 years. At present, CB loans under this facility are only given to government securitiesdealersfor inventory financing. Overnight RPs,as the name indicates, are loans of CB to banks on an overnight basis which are used to assist banks in meeting reserve deficiencies which may result from clearing lossesand/or heavier fund outflows during the preceding banking day. The rate chargedby CB is based on the interbank rate plus a certain penalty rate to encourage banks to tap other sourcesof financing before resortingto CB borrowings. Reverse RPs (RRPs) - These are transactions whereby CB borrows funds from banks using its holdingsor inventory of government securities in its portfolio as collateral with an agreement to repay the loan (and hence buy back the securities) at a specified rate and period of time. The rate at which CB borrows through this facility is based on the prevailing market rate and other considerations such as the yields on T_bills, the inflation rate and the pesodollar exchange rate, among others. Not unlike RPs, RRPs are of two kinds: term and overnight. Term RRPs usually cover a period of 7 to 14 days while overnight RRPs are just borrowings by the CB for one day. Overnight RRPs are at times used by CB to complement its borrowing under the term RRP. Considering that banks do not normally lend all their funds on a term basis since their short-term fund requirements may not warrant such an action, CB borrows these funds on overnight basis. Outright Contracts - These transactions which involve the outright purchase or sale of government securities are always carried out for the account of the CB Portfolio. In addition, only market-

SAN JOSE: MONETARY

INSTRUMENTS

AND LIQUIDITY

139

able securities are the subject of outright contracts. These government securities, which are traded at discountsand quoted on a yieldto-maturity basis,include T-bills, T-notesand other marketable securities issued by government corporations and financial institutions. At present, purchasesof marketable securitiesare done only in the secondary market since the CB, as fiscal agent of the NG, is not allowed under its Charter to participate in the primary market, i.e., the Auction. It may be noted that at present CB rarely engages in outright contracts since the market situation does not permit it to undertake this type of transaction. CB Certificates of Indebtedness (CBCIs) - The CB may also issueits own securitiesasit hasdone in the pastalthough the present policy is to phaseout thesesecurities.CBCIs were first issuedduring the 1970s to mop up excess liquidity arising from the commodity boom and to reallocate credit from urban to rural areasin support of the country's intensified agricultural program. The features of CBCIs were redesignedthrough the years to improve their marketability but these changesdid not prove to be attractive enough to investors. Meanwhile, CB Bills were introduced in March 1984 as an instrument to mop up excess liquidity arising from the nonpayment of maturing foreign loansdue to the debt moratorium. These securities have maturities not exceedingone year and are sold at a discount and on a negotiated basis. The rates on these securitiesare marketdetermined; as such, they are not eligible as reservecover. CB Bills proved to be effective in attaining their objective but were phased out beginning in October 1986 to give way to the auction of T-bills. Prior to this period, CB Bills competed with T-bills, resulting in increases interest rates. in Basedon the foregoing description of the open market instruments, the use of these instruments to attain target levels of RM and M3 may be inferred. RPs are utilized when the CB desiresto increasethe level of RM. On the other hand, when there isa needto reduce the level of RM, RRPs and the issuance of CB securities may be undertaken. It may be noted that for the useof these instrumentsto be effective it hasto be done hand in hand with interest rate policy. For example, during periodswhen a contractionary monetary policy is called for, RRPs should be priced in sucha way that banks are induced to lend to CB. Hence, through the use of open market instruments, the CB may influence not only liquidity levelsbut also interestrates. The flexibility of open market operations isan advantageof this instrument. It can be carried out in small or large stepsand at fre-

140

JOURNAL

OF PHILIPPINE

DEVELOPMENT

quent intervals so that reservesof the banking system can be adjusted on a virtually continuous basis. Finally, open market operations occur at the initiative of the CB, thereby permitting it to determine the precise volume of the transactions. This instrument, however, has limitations. For instance, RPs and RRPs have very short maturities such that the desired effects of these transactions are automatically reversed upon maturity. Given a program of sustained credit restraint, the CB resorts to continuous rollovers of the instruments. Such an approach may be costly to the CB and injects an element of uncertainty in terms of meeting the objectives of open market operations. The size of the CB's and the banking system's holding of securities that are eligible for RPs and RRPs also put transactional limits to the use of open market operations. Moreover, the present array of securities has not been useful for outright contracts because of the securities' unattractive yields. The market for these securities has remained thin, with banks acquiring the securities primarily for the "sweeteners" attached to them such as reserve eligibility and collateral value features. Hence, the effective use of open market operations for liquidity management and control would require a fairly developed financial system where there is ample supply of marketable government securities and where the market for these securities is strong. Rediscoun ting This is a transaction whereby CB purchases a bank's assetsat a discount. This instrument, as used in most LDCs, plays a dual role one as a tool to allocate credits to preferred sectors of the economy and another to influence the supply of money and credit. When rediscounting is employed, its effect becomes similar to open market operations. Rediscounting affects the reservesof banks and therefore their ability to extend credits. When the prevailing economic conditions call for a reduction in M3, CB may limit or reduce credits extended under this facility. Conversely, when the desired monetary stance is expansionary, the CB may increase the volume of rediscount credits. Rediscounting, as practised in the Philippines, is defined as the privilege extended to banks to borrow or secure loans and advances from the CB against eligible papersof their borrowers. Ever since time rediscounting was first used in the Philippines until the end of 1985, it was utilized more as a facility for credit allocation. Preferred or priority activities were afforded low rediscount rates to ensure an attractive spread between the rediscount rate and the bank's relending rate so as to encourage fund flows to these priority activities. Because of the concessional rediscount rate, demand for rediscount

SAN JOSE: MONETARY

INSTRUMENTS

AND LIQUIDITY

141

credits grew, but during periods of contractionary monetary policy, the volume of rediscountreleases was controlled. The low rediscount rate causedbanks to rely heavily on "cheap" CB financing for their credit operations, and this, to a certain extent, did not encourage domestic deposit mobilization. In cognizance of the weaknessesof this rediscounting policy and the important role that this instrument could play in liquidity management,the CB rationalized its rediscountfacility in November 1985. In particular, the rediscountrate was made market-determined to truly reflect the marginal cost of the funds of banks, ceilingson bank relending rates were lifted in line with the deregulation of interest rates,and the rediscountstructure was simplified from about 16 windows representingdifferent priority areas to just two categories: agricultural production credits and general purpose credits. The rediscount rate is being reviewed quarterly and adjusted if warranted to keep it attuned to market conditions. More frequent changes,while desirable, are felt to produce administrative problems and confusion in their implementation since most of the rediscountable papers are agricultural production credits of banks which farmers avail themselves of in the rural areas, and therefore they may not be in a position to keep abreast of frequent changesin the rates. Hence, it may be said that the facility's allocative feature dilutes its effectiveness asa liquidity managementtool. The present rediscount policy continues to bear some weaknesses. For one, the arrangement whereby the rediscount rate is adjusted on a quarterly basisdoes not provide CB with sufficient leeway to make it effective since market rates may riseand fall below the rediscount rate during a given quarter after the rediscount rate has been announced. A rediscount rate that has previously been restrictive can become expansionary if other interest rates rise. To maintain an unchangeddiscount rate policy, the CB would have to changethe discount rate frequently. Secondly,the CB rediscount rate should always be alignedwith other CB rates suchasrates on RPs and RRPs if CB's action is to be consistentin pursuingthe thrust of monetary policy. A rediscount rate that is lower than RRP rates could induce banks to borrow under the rediscount facility and lend it back under the RRP window, thereby making a profit out of CB operations. A rediscount rate that is above or below the prevailing RP rate may give confusingsignalsto the market regarding the stance of monetary policy. In the Philippines at present, it appears that it is the psychological impact of rediscount rate changes that tends to make it effective as a liquidity instrument. Quarterly changesin the rediscount rate are viewed by the banking

142

JOURNAL

OF PHI LIPPINE

DEVELOPMENT

system as signalling a general interest rate movement which the CB desiresto bringabout. Ideally, the rediscounting facility should be used to support and strengthen open market operations. For instance,when the CB wishes to complement a restrictive monetary policy, say, during a period of inflation, it usesits open market operationsto clamp down on the supply of reserves relation to a risingdemand for credit. As in a result, interest rates rise, and banks, finding their reserve position under pressure,tend to increasetheir borrowing from CB. In order to discouragethe creation of additional reservesthrough borrowing, the CB could raise the rediscount rate as market rates of interest increase. B. Portfolio Constraints

Reserverequirements Reserve requirement is traditionally employed as a protection to depositors by ensuring liquidity or solvency and, thus, the capability of the banking system to meet the withdrawals of depositors. In recent years, however, it has increasinglybeen recognizedas an important tool of monetary policy. The importance of reserve requirement for liquidity/credit control stemsfrom the fact that this variable is a very important determinant of the power of the banking system to expand credit and liquidity (on the basisof given increasesor decreases reserveratios). in Thus, reserverequirement may be saidto play a dual role in the financial system as (a) a safeguardto depositors,and (b) a liquidity/ credit managementtool. The frequency with which changes are made is generally related to the purpose for which reserve requirements have been intended. For instance, when reserverequirement is used as a solvency ratio designed to ensure the maintenance of sound banking practices and adequate protection for depositors, legal reservesare not changedvery often. On the other hand, when usedas a monetary policy tool, reserveratiosare subject to frequent changes. As a monetary policy instrument, reserverequirement issubject to important limitations. Changesin this instrument are lessflexible than open market operations. Even a small percentagechangein the reserve ratio could result in a relatively substantial adjustment in banks' credit operations. The Central Bank should not resort to changing reserve requirements if such change is expected to be reversedsoon. Thus, as an instrument of monetary policy the reserve requirement must be used cautiously since even a small changein it may have disruptive effects on the banking system. Changesin the

SAN JOSE: MONETARY

INSTRUMENTS

AND LIQUIDITY

143

reserve ratios may have differential effects on individual banks as it is likely that banks have varying levelsof liquidity, This isan important consideration in the use of this instrument particularly when the financial system is composedof very big and very small banks as in the caseof the Philippines. For instance, even if on aggregatethe banking system shows substantial excessreserves,it is possiblethat liquidity is concentrated only in a few big banks and that many other banks are already deficient in their reserves. In this case, further increasesin the reserve requirement could lead to bank failures and could havea destabilizingeffect on the economy. Direct controls Direct controls involve quantitative as well as qualitative limits on the freedom of banks to undertake certain activities. The most common types of direct controls include limitations on aggregate bank lending, selective limitations on certain types of bank lending, and interest rate regulations. They are utilized whenever the Central Bank feels that market intervention instruments do not achieve the desired results. At present, the Central Bank of the Philippines is pursuing market orientation and deregulation in its policies such that direct controls are no longer actively used. Interest rate controls were abandoned in 1983 when the last of the interest rate ceilings on loans and deposits of banks was lifted. The only remaining direct control at present is the requirement for banks to set aside a certain portion (25 percent) of their Ioanable funds for agricultural and agrarian reform credits. This requirement, however, is not a direct CB regulation but is in compliance with a presidential decree. Recently, the CB supported moves to abolish or amend this requirement since it was found to have raised the intermediation cost of banks and to have failed in its objective of increasing fund flows to the agricultural sector. C. Other Instruments

1. Prior Import Deposits - This takes the form of a requirement that importers must maintain deposits with the Central Bank or some other bank for a specified period of time as part of the funds needed for import payment. This measure tends to lock in funds for import payments as well as raise the cost of importation. In the Philippines, this instrument is not being employed by the Central Bank. While prior import deposits are required by banks from

144

JOURNAL

OF PHI LIPPINE DEVELOPMENT

importers, it is a requirement of the Bankers Association of the Philippines,and not of the CB. 2, Moral Suasion - This is an intangible yet important instrument of monetary policy that is normally employed by the Central . Bank whenever it is felt that market mechanismscould not take fully the public interest into account. It is defined as the influence that the Central Bank exercises to induce or convince banks to conduct operations in a manner that would contribute to the attainment of monetary goals but which may not be supportive of, and even contradict, profit maximization objectives of banks in the short run. It may take the form of a request for voluntary restraint on overall lending or a suggested priority in lending to different sectors of the economy. In most countries including the Philippines, this instrument is utilized by the Central Bank from time to time although its effectiveness may, to a certain extent, depend on the relationship of the Governor as head of the Central Bank with the banks. 3. Government Deposits with Central Banks - This instrument, as used in the Philippines, may be unique to this country but has thus far been effective in meeting monetary targets and objectives. This instrument involves an arrangement between the CB and the national government whereby the latter floats Treasury Securities (largely T-bills) in amounts over and above its usual requirement for financing its deficit. Proceeds from the sale of the "excess" T-bills are placed in a fixed-term deposit account with the CB for which the CB pays market interest rates (equivalent to T-bills rate for the same maturity). This arrangement, which has a neutral effect on the government's budget deficit and which has the same effect as the issuance by CB of its own instruments, was originally intended to allow the government to offset the expansionary effect on RM and M3 of the phaseout of CB Bills in favor of T-bills beginning in October 1986. Since then, the arrangement has actively been relied upon to meet monetary targets. From the standpoint of monetary management, this instrument limits CB's flexibility in controlling monetary aggregates. The CB's ability to meet monetary targets is made largely dependent on fiscal policies and decisions. For one, the volume of the weekly sale of T-bills in the auction market, as well as the acceptable bid rates, is decided by fiscal authorities. Secondly, the government's compliance with the desired and agreed upon level of its deposit that would be maintained with the CB hinges on the government's ability to live within its targeted budget deficit. In caseswhere there are shortfalls in government revenue collections and increases in expenditures vis=,_-vi, ...... . ,, it is very tempting for the govern-

SAN JOSE: MONETARY

INSTRUMENTS

AND LIQUIDITY

145

ment to withdraw these deposits for budget deficit financing. When this happens, monetary management is jeopardized. Clearly, the effective implementation of this instrument hinges on a close coordination of monetary and fiscal policies. Under the T-bill auction program, the weekly volume of flotation is announced to government securities dealers way ahead of time. Hence, any unanticipated changes in uncontrollable factors in the RM accounts would be difficult to offset through this arrangement since the volume of flotation for a given period of time shall have already been set and may no longer be changed. Moreover, this arrangement presents problems to CB in terms of offsetting very temporary or short-term swings in RM levels in-between auction dates. At present, such temporary fluctuations are being addressed through the use of RRPs and RPs but these operations are said to adversely affect auction rates. Notwithstanding the foregoing limitations, this arrangement has made the present conduct of open market operations in the Philippines more orderly since only Treasury issues (mainly T-bills) are being sold through auction unlike previously when both Treasury and CB securities with similar market features were simultaneously sold on a negotiated basis. II1. The Choice of Instruments

The choice of policy instruments in implementing a monetary policy action to achieve a target for a given period would depend on a number of factors which include: a) the state of development and structure of the financial system (i.e., whether thre is a strong government securitiesmarket) and the strength and size of individual banks comprisingthe systems; b) the nature and magnitudeof the policy action; and c) the promptness of the responseof and degree of impact on the monetary aggregate. From the discussionof the advantagesand disadvantagesof each policy instrument in the previous section and consideringthe abovementioned factors, it appearsthat (a) open market operations have a distinct advantageover the other instrumentsbecauseof their flexibility in the complexeconomicworld, (b) data tend to lagbehind events and are at times insufficient to fully discloseemergingconditions/developments in the financial system. Becauseof this, adaptations or changesin policies tend to be undertaken in a gradual or step-by-stepmanner so that they can be readily modified or reversed whenever necessaryas real conditions/developmentsbecome clear to

146

JOURNAL

OF PHILIPPINE

DEVELOPMENT

polio/makers. Open market operationsare the best instrument suited to the step-by_stepadaptation of monetary policy since they can be usedto initiate small policy actionsor to aggressively carry out large changes in reservesover relatively shorter periods of time. They are continuous in nature, can be undertaken quickly and are subject to ready modification and reversal.Open market operations can therefore take the lead in general monetary policy implementation, with changesin other instruments only to supplementand reinforce the initiative. Reserve requirement as a tool can be inflexible since it could not be changedas frequently as open market operations. The effect of frequent changesin the reserveratio may be adverseparticularly when the structure of the financial system is such that there is large variation in levels of liquidity among banks. For example, frequent increasesin the reserverequirement may push small and weak banks to the brink of collapseas thesebanks may find it difficult to adjust to thesechanges.Moreover, a high reserverequirement diverts a significant portion of bank funds to low or nonyielding assetsand increasesthe cost of intermediation which tends to discouragethe development of the banking system. Hence, this instrument may be used if it is felt that the need to provide or absorb reservesis longlastingor would prevail for a long period of time. Similarly, rediscounting may not also be as flexible as open market operations. Once a rediscount rate is announced, it must be kept for some time before revising it. The effect on the monetary target may be impreciseand not immediate sincethere could stillbe a significant demand for rediscounting loansdespite upward adjustments in the rate, unlessquantitative limits or quotas are set. While the foregoing showsthe relative advantagesof open market operations vis-a-vis other instruments, it cannot be concluded that it is by itself sufficient to attain the targets and goalsof monetary policy. What is important in the implementation of any monetary policy action is consistencyand harmonization in the use of variousinstrumentsavailableto the CB.

Você também pode gostar

- Summary of Anthony Crescenzi's The Strategic Bond Investor, Third EditionNo EverandSummary of Anthony Crescenzi's The Strategic Bond Investor, Third EditionAinda não há avaliações

- Must Read BOPDocumento22 páginasMust Read BOPAnushkaa DattaAinda não há avaliações

- World Bank Debt Management: Questions and AnswersDocumento20 páginasWorld Bank Debt Management: Questions and Answersk_Dashy8465Ainda não há avaliações

- ShadzDocumento13 páginasShadzAjinkya AgrawalAinda não há avaliações

- Balance of Payment AdjustmentDocumento37 páginasBalance of Payment AdjustmentJash ShethiaAinda não há avaliações

- Fiscal and Monetary Policy Interface: Recent Developments in IndiaDocumento8 páginasFiscal and Monetary Policy Interface: Recent Developments in IndiaDipesh JainAinda não há avaliações

- Reserve Requirements Empirical Nov 2011Documento35 páginasReserve Requirements Empirical Nov 2011Ergita KokaveshiAinda não há avaliações

- External Vulnerability and Financial Fragility in BRICS Countries: Non-Conventional Indicators For A Comparative AnalysisDocumento8 páginasExternal Vulnerability and Financial Fragility in BRICS Countries: Non-Conventional Indicators For A Comparative AnalysisartreguiAinda não há avaliações

- Public Borrowing and Debt Management by Mario RanceDocumento47 páginasPublic Borrowing and Debt Management by Mario RanceWo Rance100% (1)

- Money Laundering Governance FrameworkDocumento15 páginasMoney Laundering Governance FrameworkSushma SrinivasaAinda não há avaliações

- Public Debt Management Techniques and ObjectivesDocumento21 páginasPublic Debt Management Techniques and ObjectivesAbhishek Nath TiwariAinda não há avaliações

- Monetary Policy and Economic Growth: An Islamic PerspectiveDocumento10 páginasMonetary Policy and Economic Growth: An Islamic PerspectiveDwi Adi MuktiAinda não há avaliações

- 3 Bank Negara, Monetary PolicyDocumento67 páginas3 Bank Negara, Monetary Policycharlie simoAinda não há avaliações

- Ciecrp 4Documento38 páginasCiecrp 4Martin ArrutiAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment - Credit PolicyDocumento10 páginasAssignment - Credit PolicyNilesh VadherAinda não há avaliações

- EASIER TECHNIQUES FOR BALANCE OF PAYMENTS ANALYSISDocumento13 páginasEASIER TECHNIQUES FOR BALANCE OF PAYMENTS ANALYSISHatem HassanAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Money SupplyDocumento3 páginasFactors Affecting Money Supplyananya50% (2)

- Basel III - Potential Impact On Financial Institutions - Paul Gallacher January 10 2013Documento3 páginasBasel III - Potential Impact On Financial Institutions - Paul Gallacher January 10 2013api-87733769Ainda não há avaliações

- Cash Management and Debt Management: Two Sides of The Same Coin?Documento77 páginasCash Management and Debt Management: Two Sides of The Same Coin?Nobody619Ainda não há avaliações

- Balance of PaymentsDocumento12 páginasBalance of PaymentsFebbyAinda não há avaliações

- Jose Sanchez Fung - Estimating The Reaction Function of The Monetary Policy in DRDocumento16 páginasJose Sanchez Fung - Estimating The Reaction Function of The Monetary Policy in DRAnderson TorresAinda não há avaliações

- Macro Economics AssignmentDocumento10 páginasMacro Economics AssignmentSithari RanawakaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 13 End-Chapter Essay Questions SolutionsDocumento21 páginasChapter 13 End-Chapter Essay Questions SolutionsHeidi DaoAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Money SupplyDocumento3 páginasFactors Affecting Money Supplycuriben100% (5)

- RBI Classification of MoneyDocumento11 páginasRBI Classification of MoneyTejas BapnaAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter - Money Creation & Framwork of Monetary Policy1Documento6 páginasChapter - Money Creation & Framwork of Monetary Policy1Nahidul Islam IUAinda não há avaliações

- Answers To Technical Questions: 14. Open Market Operations of SBPDocumento10 páginasAnswers To Technical Questions: 14. Open Market Operations of SBPfaisalAinda não há avaliações

- Abm161 Lessons 8 9 2023Documento24 páginasAbm161 Lessons 8 9 2023Norhaliza D. SaripAinda não há avaliações

- Independence? Discuss at Least Two Cases Which Contributed To The Bankruptcy of The Old Central Bank ofDocumento3 páginasIndependence? Discuss at Least Two Cases Which Contributed To The Bankruptcy of The Old Central Bank ofHazel Gayle De PerioAinda não há avaliações

- Impact of Liquidity On Market Capitalization EdelwiseDocumento39 páginasImpact of Liquidity On Market Capitalization Edelwisekharemix0% (2)

- Chap4 PDFDocumento22 páginasChap4 PDFexodc2Ainda não há avaliações

- 9 WP Irp PDF AngDocumento22 páginas9 WP Irp PDF AngAfrim AliliAinda não há avaliações

- Avantage ESA95vsCashaccountingDocumento14 páginasAvantage ESA95vsCashaccountingthowasAinda não há avaliações

- Ec Quiz Fiscal&Monetarypolicyii AnswersDocumento4 páginasEc Quiz Fiscal&Monetarypolicyii AnswersAjey BhangaleAinda não há avaliações

- Monetary Policy Transmission MechanismDocumento29 páginasMonetary Policy Transmission MechanismVenkatesh SwamyAinda não há avaliações

- Monetary Policy of the Philippines ExplainedDocumento24 páginasMonetary Policy of the Philippines ExplainedDarwin SolanoyAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Conditions Indexes: A Fresh Look After The Financial CrisisDocumento55 páginasFinancial Conditions Indexes: A Fresh Look After The Financial CrisisnihagiriAinda não há avaliações

- Ec103 Week 09 and 10 s14Documento44 páginasEc103 Week 09 and 10 s14юрий локтионовAinda não há avaliações

- Bispap 60 GDocumento7 páginasBispap 60 GraghibAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction to the Money Supply Process and How Deposits Impact M1Documento3 páginasIntroduction to the Money Supply Process and How Deposits Impact M1amitwaghelaAinda não há avaliações

- Barclays Brazil A Guide To Local Markets - Finding Value in A Controlled EnvironDocumento26 páginasBarclays Brazil A Guide To Local Markets - Finding Value in A Controlled Environmvidhya50Ainda não há avaliações

- Print Money4Documento23 páginasPrint Money4Alkaton Di AntonioAinda não há avaliações

- WUFC Issue 17 - FinalDocumento5 páginasWUFC Issue 17 - FinalwhartonfinanceclubAinda não há avaliações

- India's experience implementing reforms to monetary policy frameworkDocumento16 páginasIndia's experience implementing reforms to monetary policy frameworkDr-Manju N MysuruAinda não há avaliações

- TD 2014.04 - Versão FinalDocumento43 páginasTD 2014.04 - Versão Finaljc224Ainda não há avaliações

- Chapter - 3 Reserve Bank of India: Monetary Policy and InstrumentsDocumento10 páginasChapter - 3 Reserve Bank of India: Monetary Policy and Instrumentsanusaya1988Ainda não há avaliações

- Basic of Money Supply, Money Supply: Section BDocumento14 páginasBasic of Money Supply, Money Supply: Section Baju1981Ainda não há avaliações

- BSP Tools and Monetary PolicyDocumento21 páginasBSP Tools and Monetary PolicyApple Jane Galisa SeculaAinda não há avaliações

- Monetary and Credit Policy of RBIDocumento9 páginasMonetary and Credit Policy of RBIHONEYAinda não há avaliações

- Name: Olufisayo Babalola Matric Number: 169025002 Course: Fin 913 Question: Discuss The Indices of Financial DevelopmentDocumento14 páginasName: Olufisayo Babalola Matric Number: 169025002 Course: Fin 913 Question: Discuss The Indices of Financial Developmentfisayobabs11Ainda não há avaliações

- Mms Ier Final Feb23Documento30 páginasMms Ier Final Feb23ahmedrostomAinda não há avaliações

- Topic 3Documento4 páginasTopic 3jay diazAinda não há avaliações

- Money Market Dynamics: Golaka Nath and N. Aparna RajaDocumento14 páginasMoney Market Dynamics: Golaka Nath and N. Aparna Rajamalikrocks3436Ainda não há avaliações

- Fiscal Deficits and Inflation Stabilization in RomaniaDocumento32 páginasFiscal Deficits and Inflation Stabilization in RomaniakillerbboyAinda não há avaliações

- Public Borrowing and Debt ManagementDocumento53 páginasPublic Borrowing and Debt Managementaige mascod100% (1)

- Monetary Policy CourseworkDocumento8 páginasMonetary Policy Courseworkafjwfealtsielb100% (2)

- Lebanon Economic SummaryDocumento3 páginasLebanon Economic SummaryGerard ArabianAinda não há avaliações

- Monetary Policy and Financial Market Performance: BY: Dhanishtha Anand Nipun Sehrawat Parmeet Sethi Prashansa MohanDocumento24 páginasMonetary Policy and Financial Market Performance: BY: Dhanishtha Anand Nipun Sehrawat Parmeet Sethi Prashansa MohanNiPun SehrawatAinda não há avaliações

- Major Duties of Central Banks: Monetary Policy, Bank Regulation, Financial StabilityDocumento25 páginasMajor Duties of Central Banks: Monetary Policy, Bank Regulation, Financial StabilitySakkarai ManiAinda não há avaliações

- Innov. in Banking Proj.Documento6 páginasInnov. in Banking Proj.Yog CoolAinda não há avaliações

- Pension Loan - Ateam PresentationDocumento4 páginasPension Loan - Ateam PresentationApple CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Pension Loan - Ateam PresentationDocumento4 páginasPension Loan - Ateam PresentationApple CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Case GetEVee PDFDocumento17 páginasCase GetEVee PDFApple CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Ufc 4-310-02n Design - Clean Rooms (16 January 2004)Documento70 páginasUfc 4-310-02n Design - Clean Rooms (16 January 2004)Bob VinesAinda não há avaliações

- The Work of The Word Part 2Documento14 páginasThe Work of The Word Part 2Apple CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Mariah Jobelle SDocumento4 páginasMariah Jobelle SApple CruzAinda não há avaliações

- 10 Hotels in Metro ManilaDocumento5 páginas10 Hotels in Metro ManilaApple CruzAinda não há avaliações

- Aquino JaneDocumento4 páginasAquino JaneApple CruzAinda não há avaliações

- ModelingDerivatives GalleyDocumento268 páginasModelingDerivatives Galleygdellanno100% (1)

- A.investment A Pays $250 at The Beginning of Every Year For The Next 10 Years (A Total of 10 Payments)Documento4 páginasA.investment A Pays $250 at The Beginning of Every Year For The Next 10 Years (A Total of 10 Payments)EjkAinda não há avaliações

- CH10Documento20 páginasCH10superuser10100% (1)

- Keown Tif 19 FINALDocumento38 páginasKeown Tif 19 FINALchiji chzzzmeowAinda não há avaliações

- Treasury BillsDocumento18 páginasTreasury BillsHoney KullarAinda não há avaliações

- 17 F F6 Vietnam Tax FCT Answers For Multiple Choice Questions 2015 Exam enDocumento15 páginas17 F F6 Vietnam Tax FCT Answers For Multiple Choice Questions 2015 Exam endomAinda não há avaliações

- Fin 221 Fall 2006 Exam 1: Multiple ChoiceDocumento7 páginasFin 221 Fall 2006 Exam 1: Multiple Choicesam heisenbergAinda não há avaliações

- Bond Valuation ChapterDocumento7 páginasBond Valuation ChapterGene Goering IIIAinda não há avaliações

- RaginiDocumento92 páginasRaginipiyushborade143Ainda não há avaliações

- Bond Pricing and Bond Yield New - 1Documento66 páginasBond Pricing and Bond Yield New - 1Sarang Gupta100% (1)

- Topic 1: Overview of Financial Systems Test 1 SECTION1: Match The Terms With Suitable Explanations ExplanationsDocumento33 páginasTopic 1: Overview of Financial Systems Test 1 SECTION1: Match The Terms With Suitable Explanations Explanationsnghiep tranAinda não há avaliações

- Manajemen Investasi - Modul (IBN)Documento130 páginasManajemen Investasi - Modul (IBN)Fajar Ariesman100% (1)

- Ecs2602 MCQ Testbank PDFDocumento74 páginasEcs2602 MCQ Testbank PDFPaula kelly100% (1)

- Project Report On Inflation NewDocumento78 páginasProject Report On Inflation NewArjun JhAinda não há avaliações

- US Treasury and Repo Markt ExerciseDocumento3 páginasUS Treasury and Repo Markt Exercisechuloh0% (1)

- The U.S. Treasury Yield Curve: 1961 To The Present: Refet S. Gu Rkaynak, Brian Sack, Jonathan H. WrightDocumento14 páginasThe U.S. Treasury Yield Curve: 1961 To The Present: Refet S. Gu Rkaynak, Brian Sack, Jonathan H. WrightGreta Manrique GandolfoAinda não há avaliações

- Short-Run Behavior of Defensive Assets in The Ethiopian Commercial Banking SectorDocumento25 páginasShort-Run Behavior of Defensive Assets in The Ethiopian Commercial Banking SectorEndrias EyanoAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 3 Bond Duration and Bond PricingDocumento28 páginasChapter 3 Bond Duration and Bond PricingClaire VensueloAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Analysis of Banking DocumentsDocumento3 páginasFinancial Analysis of Banking Documentsrifat AlamAinda não há avaliações

- Updates in Financial Reporting Standards: Northeastern CollegeDocumento3 páginasUpdates in Financial Reporting Standards: Northeastern CollegeJobelle Grace SorianoAinda não há avaliações

- Homework Week6Documento2 páginasHomework Week6Baladashyalan RajandranAinda não há avaliações

- 04 Task Performance 1Documento4 páginas04 Task Performance 1Camille MadlangbayanAinda não há avaliações

- PDST Calculation GuidelinesDocumento9 páginasPDST Calculation GuidelinesmarkoyelleAinda não há avaliações

- TBAC Presentation Q2 2020Documento31 páginasTBAC Presentation Q2 2020ZerohedgeAinda não há avaliações

- Tarheel Consultancy Services: BangaloreDocumento170 páginasTarheel Consultancy Services: BangaloreSumit SinghAinda não há avaliações

- Capital-markets-Midterm With ExplanationDocumento9 páginasCapital-markets-Midterm With ExplanationfroelanangusatiAinda não há avaliações

- Government Securities Market Development The Indonesia CaseDocumento31 páginasGovernment Securities Market Development The Indonesia CaseADBI EventsAinda não há avaliações

- Bond Valuation ActivityDocumento3 páginasBond Valuation ActivityJessa Mae Banse LimosneroAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 10 Futures Arbitrate Strategies Test BankDocumento6 páginasChapter 10 Futures Arbitrate Strategies Test BankJocelyn TanAinda não há avaliações

- Bond Markets ExplainedDocumento22 páginasBond Markets ExplainedSumonaminur100% (1)

- Nine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesNo EverandNine Black Robes: Inside the Supreme Court's Drive to the Right and Its Historic ConsequencesAinda não há avaliações

- Reading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismNo EverandReading the Constitution: Why I Chose Pragmatism, not TextualismAinda não há avaliações

- Reasonable Doubts: The O.J. Simpson Case and the Criminal Justice SystemNo EverandReasonable Doubts: The O.J. Simpson Case and the Criminal Justice SystemNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (25)

- Summary: Surrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNo EverandSummary: Surrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)

- University of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingNo EverandUniversity of Berkshire Hathaway: 30 Years of Lessons Learned from Warren Buffett & Charlie Munger at the Annual Shareholders MeetingNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (97)

- O.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth about the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron GoldmanNo EverandO.J. Is Innocent and I Can Prove It: The Shocking Truth about the Murders of Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron GoldmanNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (2)

- The Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterNo EverandThe Killer Across the Table: Unlocking the Secrets of Serial Killers and Predators with the FBI's Original MindhunterNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (456)

- The Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern CrimeNo EverandThe Invention of Murder: How the Victorians Revelled in Death and Detection and Created Modern CrimeNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (142)

- Your Deceptive Mind: A Scientific Guide to Critical Thinking (Transcript)No EverandYour Deceptive Mind: A Scientific Guide to Critical Thinking (Transcript)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (31)

- Getting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorNo EverandGetting Through: Cold Calling Techniques To Get Your Foot In The DoorNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (63)

- How To File Your Own Bankruptcy: The Step-by-Step Handbook to Filing Your Own Bankruptcy PetitionNo EverandHow To File Your Own Bankruptcy: The Step-by-Step Handbook to Filing Your Own Bankruptcy PetitionAinda não há avaliações

- The Edge of Innocence: The Trial of Casper BennettNo EverandThe Edge of Innocence: The Trial of Casper BennettNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (3)

- Dictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersNo EverandDictionary of Legal Terms: Definitions and Explanations for Non-LawyersNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (2)

- I GIVE YOU CREDIT: A DO IT YOURSELF GUIDE TO CREDIT REPAIRNo EverandI GIVE YOU CREDIT: A DO IT YOURSELF GUIDE TO CREDIT REPAIRAinda não há avaliações

- Win Your Case: How to Present, Persuade, and Prevail--Every Place, Every TimeNo EverandWin Your Case: How to Present, Persuade, and Prevail--Every Place, Every TimeNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (41)

- Limited Liability Companies For Dummies: 3rd EditionNo EverandLimited Liability Companies For Dummies: 3rd EditionNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (8)

- The Book of Writs - With Sample Writs of Quo Warranto, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, and ProhibitionNo EverandThe Book of Writs - With Sample Writs of Quo Warranto, Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Certiorari, and ProhibitionNota: 5 de 5 estrelas5/5 (9)

- The Law Says What?: Stuff You Didn't Know About the Law (but Really Should!)No EverandThe Law Says What?: Stuff You Didn't Know About the Law (but Really Should!)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (10)

- The Edge of Doubt: The Trial of Nancy Smith and Joseph AllenNo EverandThe Edge of Doubt: The Trial of Nancy Smith and Joseph AllenNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (10)