Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

9th Circuit Appellant Response To Amici Curiae of Cities Palo Alto Menlo Park Atherton

Enviado por

iridiumstudent0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

18 visualizações49 páginas010485

Título original

9th Circuit Appellant Response to Amici Curiae of Cities Palo Alto Menlo Park Atherton

Direitos autorais

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documento010485

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

0 notas0% acharam este documento útil (0 voto)

18 visualizações49 páginas9th Circuit Appellant Response To Amici Curiae of Cities Palo Alto Menlo Park Atherton

Enviado por

iridiumstudent010485

Direitos autorais:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Formatos disponíveis

Baixe no formato PDF, TXT ou leia online no Scribd

Você está na página 1de 49

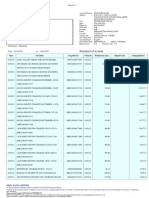

FARROH, SCHILDI-Ll\USE, VHLSO;:J & RAINS

Including A Professional Corporation

Harold R. Farrow

Orner L. Rains

Robert M. Bramson

Senator Office Building

1121 "L" Street, Suite 808

Sacramento, California 95814

(916) 447-2000

Attorneys for Appellant

IN THE UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

PREFERRED COMH.UNICATIONS, INC., )

a California corporation, )

)

Appellant, )

)

v. )

)

CITY OF LOS Al:rGELES, CALI FOfu"1 lA, )

a municipal corporationr and )

DEPARTMENT OF AND )

a municipal utility, )

)

Appellees. )

---------------------------------)

No. 84-5541

RESPONSE

TO BRIEF OF MlICI CURIAE

OF THE CITIES OF PALO ALTO,

PARK ATHERTON

I. IW;:'RODUCT ION

A. Assumed By Palo Alto Are

To Those Pled Below And Are Incorrect

B. Acceptance of Palo Alto's Legal Arguments

Hould Require A Radical Reordering Of

Consti tutional Rights, And \'lould Require

A Rewriting Of The First Amendment

II. Pl\LO ALTO ['4ISUNDERSTANDS AND :v1ISCHARACTERIZES

THE POSTURE OF THIS CASE

III. PALO ALTO'S TO DEVALUE

FIRST A..'1ENDt<1ENT RIGHTS, AND THUS TO AVOID

CONSTITUTIONAL OF ITS

EXCLUSION, MUST FAIL

A. The Consti tutio':1 Protects The

Of Dissemin3.tion As Hell As The

Dissenination Itself

B. The Re-Publication of Another's Vie'.Ns Is

Entitled To Full CO::1stituti,)!,lal P:ot'-=ctiol1

C. Palo Ai to I s Rei i ance UpO::1 It I..J.-=-=lSed

Access" Is :'1isplaced

IV. PALO ALTO I S CLAIMED INTEREST IN FIR3T

VALJES" IS .mOLLY ':7 U''1.)'JT lE7..1-::'

V. PALO ALTO .r>,.:D

MISAPPLIES THE TEST

A. The O'Brien Test Does Not App

To The F:1cts At Issue

B. The Requirements of the O'Brien

Test Are Not Het

1. It Is Los Angeles' Interest

Not Palo Alto's Guesses About

Them, ilhich f1ust be Llenti fiea

2. Palo Alto's Suggested "Interest"

Are Improper

3 "Cream Skimming"

i.

PAGES

1

1

5

7

10

11

13

13

23

26

26

30

30

31

32

r;:'AB LS ()

Continued

PAGES

4. Access Channels 34

5. Cornputer-to-Computer Data Transmission 35

6. Disruption of Rights-of-Way 37

VI. CONCLUSION 42

ii.

TABLE OF

CASE PAGE(S)

Adderley v. Florida, 385 U.S. 39 (1966)

Associated Film Distribution Corp. v

Thornburgh, 520 F.Supp. 971 (E.D. ?a. 1981)

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan

372 U.S. 58 (1963)

Bol er v. Youn 's Drug Products Corp.

u.S. , 77 L.Ed.2d 469 1983)

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, (1976)

Capitol v. Mitchell

F.Supp.

Catalina Cablevi3ion Associates v. City of Tucson

745 F.2d 1266 (9th eire 1984)

Century Federal, Inc. v. Palo Alto

579 F.Supp. 1553 (N.D. Cal. 1984)

Cinevision Corp. v. City of Burbank

745 F.2d 560 (9th Cir. 1984)

Cit Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpavers For Vincent

U.S. , 52 U.S.L.W. 4594 May 15, 1384

Clark v. Community F.or Creative

U.S. , 52 U.S.L.W. 4986 (June 29, 1984)

Community Communications Co. v. City

+

of Boulder

630 F.2d 704 (10th Cir. 1980),

rev'd 455 U.S. 40 (1982)

Co. v. City of Soulder

485 F.Supp. 1035 (D.Colo.) rev'd 630 F.2d

704 (10th Cir. 1980) reinstated 455 U.S. 40 (1982)

Community Communications Co. v. Boulder

660 F.2d 1370 (lOt, eire 1981)

Cox C1.ble CommunicClti'):13, Inc. v. Si-:l;?ST1

569 F.2d 507 (D.Neb. 1983)

Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347 (1976)

38

12

15

19

24

17

5

1-5

16,37-40

29

28

4, 42

9

34

32, 37

7

l

CASE PAGE S

FCC v. League of Women Voters,

52 U.S.L.H. 5008 5020 (July 2,

U.S.

1984)

25

FCC v. Midwest Video

440 U.S. 689 (1979)

18

United Artists Inc. 14

Frost v.

271 U.S.

Railroad Commission

573 (1926)

of Calif0rnia 32, 37

Grayned v. City Qf

408 U.S. 104 (1972)

Rock fori 39

Grosjean

297 U.S.

v. American

293 (1936)

Press Co. 15, 20, 35

Home Box Office.

567 F.2d 9 (D.C.

cert. 434

Inc. v. F.C.C.

eir.),

U.S. 829 (1977)

14

Interstate Circuit v.

390 U.S. 676 (1968)

Da:las

1 -

.::J

Kash Enterprises, Inc.

19 Cal.3d 294 (1977)

v. City of Los Angeles 12

Metromedia, Inc. v.

453 U.S. 490 (L981)

San Diego 28, 31

Miami Herald PUb. Co. v. Hallandale

734 F.2d 666 (11th Cir. 1984)

12

Hiami Herald Publishing

18 U.S. 241 (1974)

Co. v. Tornillo, 15, 18, 24,

Midwest Video Corp. v. FCC, 571 F.2d

1978) aff'd on other grounds

440 U.S. 689-(1979)

1025 21,

34,

25,

37

32,

"'linneapolis

U.S.

St:"lr v. i1in"1esot,:'i

,75 B L.Ed.dd 295 (1983)

:)f Revenue 35

Moffett v.

228 (D. Conn.

11ian,

1973)

360 F.Supp. 20

v. Alabama Educational Television

688 F.2d 1033 (3t'1 eire 1982) --

15

MurJ0ck V. sylvania,

319 U.S. 105

ii.

Pl\GE (S )

Perry Education Assn. v. Perry Local Educators' Assn. 37 , 96

460 U.S. 37 (1983)

For Better SDvironnent 20

Sec. of '1:).(:;1,'1.11 v.T.H. 'IllS)' '.

I U.S. 52 U.S.L.ll. 4875 (June 26, 1984)

Southern New Jersey Newspapers v. State of New Jersey

54 2 F. S u pp. 1 7 3 (D. 1-1 J. 1982 )

Stromberg v. 283 U.S. 359 (1'331)

Carr. v. C3S

415 U. S . 394 (1 'J 74- )

T'21'3vi.3i:::):1 Trans:nission v. Pub. Uti1. c:':')'1l.

47 Cal.2d 82 (1956)

U.S. Postal Service v. Council of Greenbur h

Civic 453 U.S. 114 1981)

United St-".te:3 \l. 710 F.2d 141)

(9th Cir. 1933)

United States v. 'Hr1',,.,est Video Sorp.

406 U.S. 649 (1972)

United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968)

20

12-13

29

14

32

20

14

26-30

I:lc. 17

Yo un v. A.r:1e r i C3. '1 in i 'rhea 17

427 U.S. 50 \1976

Weaver v. Jordan, 64 Cal.2d 235 (1966) 12

Wollan v. City of Palm Springs 12

59 Cal.2d 276 (1963)

OTHER

Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 10

Cal. Pub. Util. Code, Section 767.5 39

Tribe, American Constitutional 28

iii.

I. INTRODUCTION

The Cities of Palo Alto, Menlo Park, and the Town of

Atherton (hereinafter referred to collectively as "Palo Alto"),

have filed a brief amici curiae, urging this Court to affirm the

decision entered below. However, the arguments made by Palo Alto

are not only legally inaccurate, but also improperly assume facts

which are contrary to those pleaded below and which have in ct

been proven to be false in the context of the very case in which

Palo Alto is a defendant.

A. Facts Assumed Bv Palo Alto Are ContrarY

To Those Pled &'ld Are Incorrect"

Counsel for Preferred is uniquely familiar with the

arguments contained in Palo Alto's brief. Those arguments are

taken almost verbatim from Palo Al to' s of Points anil

Authorities in Support of Motion for Summary Jujgment" in Century

Federal, Inc. v. City of Palo Alto, et al., No. C-83-4231-EFL

1

(N.D. Cal.). Counsel for Preferred is also counsel for

plaintiff Century Federal, Inc. in that case. As might be

expected in a summary judgment motion, Palo Alto relied upon a

lengthy list of (purportedly) undisputed facts in requesting the

1 See, Century Federal v. City of Palo Alto, 579 F.Supp. 1553

(N.D. Cal. 1984). By order dated November 21, 1984, District

Judge Lynch on his own motion removed from calendar both the

Cities' Motion for Summary Judgment and the Plaintiff's

Cross-motion for Partial Summary Judgment.

-1

Century Federal District Judge to grant its motion. Palo Alto

now presents the same arguments to this Court, but asks it to

assume --in ruling upon an appeal of grant of a Rule 12(b)(6)

motion-- the truth of those facts. Yet those facts are directly

contrary to the facts pled in the complaint below, and have in

fact been demonstrated to be untrue by the plaintiff in Centur

Federal.

As did the complaint in the instant case, the complaint

in the Century Federal case alleged that no physical or economic

scarcity characterized the provision of cable television services

in the market at issue. Similarly, both complaints alleged that

there was no significant disruption from having multiple, as

opposed to one, cable television systems in public rights-of-way

in the same city. As did the defendants below, Palo Alto in

Century Federal attempted simply to disregard those allegations,

or to assume their falsity. However, unlike the court below, the

court in Century Federal correctly held that the plaintiff must

be afforded the opportunity to prove the truth of those

allegations. Century Federal, Inc. v. Palo Alto, 579 F.Supp. at

1562 et ~ Yet, in its Hotion for Summary Judgment (and,

hence, in its amici brief), Palo Alto again attempts to "assume"

facts which it believes support its position.

However, in the Century Federal litigation, the

plaintiff has now proven that its allegations were correct, and

that Palo Alto's "assumed facts" are false. See, "Statement of

Undisputed Facts" (Exhibit 1) excerpted from Century Federal's

cross-motion for partial summary judgment. Submitted to the

Century Federal District Court were the Declaration of John

-2

Biggins (the author of Pacific Telephone's cable televisi0n

construction manual) (Exhibit 2), the Declaration of Wayne Lagger

(the present "CATV Coordinator" for Pacific Bell) (Exhibit 3),

and the Declaration of Kenneth Thomas (Exhibit 4), president of a

major engineering/consulting firm (together with that firm's

eX'!1austive study), to prove that there is no physical licnitation

on the number of cable tel ev i s ion compani es \"hi ch ::lay be

accomodated in the Cities of Palo Alto, Menlo Park and Atherton.

These declarations also show that with modern cable television

system construction methods, there is no significant added

inconvenience or disruption from having two, as opposed to one,

cable television companies construct their systems at the same

time.

There is also submitted in the

litigation the Declaration of Dr. Leonard Tow (Exhibit 5),2 an

economist and former university and the president of

one of the largest cable television c0mpanies in the United

States. Dr. Tow has 20 years of experience in t'!1e cable

television industry. His declaration establishes that cable

television is not characterized by economic scarcity, i.e., that

cable television is not a natural monopoly in Palo This is

a fact we believe we could also prove to be true in Los Angeles.

2 The attachments to Dr. Tow's Declaration, amounting to

approximately 1000 pages, have not been supplied -- in an attempt

to keep the Court's file down to manageable size. Preferred

will, of course, immediately provide these documents if the Court

so desires.

-3

The Declaration of Dr. William Lee (Exhibit 6), a professor of

journalism, notes that, in any case, the large number of cities

with only one newspaper provides no occasion for franchising

newspapers, and that, accordingly, there is no need to

"franchise" cable television operators. Finally, Dr. Lee "llso

explains in detail the extraordinary injury to journalistic

freedom presently caused by the (often successfUl) attempts of

local governments to control numerous aspects of cable television

' , , 3

d lssemlnatlon.

Preferred believes that it is crucial for the Court to

be aware of this evidentiary background in the Century Federal

case when it assesses the arguments made by Palo Alto herein.

This is true because of the prevalence of cert"lin widespread

"myths" about cable television which, though having a certain

amount of intuitive appeal, turn out to be completely without

basis in fact. some of these nyths of which

may have been accurate when applied to the early days of

community antenna television, but which have no relevance to

modern day cable television), have appeared to form the basis for

3 This "total control", and its attendant chill, of

cablecasters by local government is not speculative or

hypothetical, as a case presently pending before this Court

demonstrates. See Pacific West Cable Co. v. City of Sacramento,

et al., No. 84-2373, Appellant's Opening Brief at 10. The

factual record before this Court in that case constitutes a livid

example of the extraordinary burdens on journalistic freedom

which are born of the franchise auction process. See also,

Community Communications Co. v. City of Boulder, 630 F.2d 704,

712, n.8, 713, 719-20 (10th Cir. 1980) (Markey, C.J.,

dissenting), panel majority rev'd, 455 U.S. 40 (1982).

-4

some past judicial decisions --particularly decisions in

non-constitutional contexts, where the courts Of '-en need not and

do not scrutize the particular factual assertions presented to

them. See, e.g., Catalina Cablevision Associates v. City of

Tucson, 745 F.2d 1266 (9th Cir. 1984). Preferred believes that

the record in Century Federal establishes an point:

Though the facts alleged in the complaint in this case may be

contrary to certain widely accepted beliefs, this by no means

indicates that those alleged facts cannot be proven -- rather, it

is the "myths" which will be proven to be without basis in fact.

As the Century Federal record indicates, the rule that all

well-pleaded allegations must be accepted as true, is a wise

one. The court below failed to follow this rule, and its

judgment must be reversed.

B. Acceptance of Palo Alto's Legal Arguments

Would Reauire A Radical Reordering Of

Constituti:::mal Rights, AJ1d "dould Require

A Rewriting Of The First

Palo Alto makes two separate arguments. First, it

claims that plaintiff has no First rights except when

engaging in one very narrm'J acti vi ty, and that Los Angeles has

not stopped Preferred from engaging in that activity. Second,

Palo Alto claims that Los exclusion of Preferred is

"justified" because of the resulting control which Los Angeles

has gained over its selected cable television operator. As is

shown below, both of these arguments are legally erroneous.

However, some preliminary observations are helpful.

-5

As it must, given the allegations of the complaint, Palo

Alto does not purport to base its arguments upon any "u:1ique"

characteristics of cable television which might Cl.rguably provide

some basis for distinguishing cases i:1volving other First

Amendment speakers. Rather, Palo Alto presents a theory of the

Constitution which it must (and appare:1tly does) contend applies

across the board to all First & ~ e n d ~ e n t speakers. If Palo Alto's

theories are correct as applied to Preferred, then they must also

be correct as applied to newspapers, movie theaters, and all

other First Amendment speakers. Conversely, if --as is in fact

the case-- innumerable decisions have already explicitly or

implicitly rejected those theories as applied to newspapers,

etc., then they must also be rejected in the context of this case.

One of Palo Alto's fundamental beliefs is apparently

that all it (or rather Los Angeles) need demonstrate to this

Court is that some "public good" has been gained by Preferred's

exclusion from access to willing listeners. Palo Alto apparently

believes that the means used to obtain the "governmental

interests" are completely irrelevant. Thus, Palo Alto recognizes

that its suggested "interests" could not constitutionally be

obtained through the use of proper police power regulation -

that is, neutral, narrowly tailored enactments applicable to all

on a non-discriminatory basis. Rather, Palo Alto boldly explains

that if Los Angeles does not exclude Preferred from the market,

and provide a different operator with a government-protected

monopoly, then it will lose the power to extract "concessions."

As Palo Alto puts it, without a franchise auction process, "a

city forfeits the leverage necessary to obtain such concessions

-6

from a ... cable operator. Put simply, an operator will have no

reason to a ee [to provide free benefits to t ~ e public] if the

municipality cannot exact those concessions as the price of

admission." (Amici Br. at 29). However, by acknowledging the

fact that the attainment of its "interests" is beyond proper

police power, Palo Alto ~ e r e l y underscores t ~ e fact that the

municipal actions involved are unconstitutional. A governmental

body is forbidden from using the power to grant or deny a benefit

or authorization in such a way as to atteQpt to obtain

"agreeQent II to inproper requ i rements . "The den i 3.1 0 f a publ i c

benefit may not be used by the governnent for the purpose of

creating an incentive enabling it to achieve what it may not

command directly." Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347, 361 (1976). In

a nutshell, Palo Alto urges as justification for Los Angeles'

unconstitutional exclusion of Preferred from its audience that

Los Angeles has been successful in achjeving "What it [could] not

command directly". Palo Alto's "justifications" are themselves

admissions about the unconstitutional and corruptive nature of a

process amounting to nothing more nor less than an auctioning off

to the highest bidder of the right to engage in free speech.

In its brief, Palo Alto seriously misunderstands what

issues it is necessary for this Court to resolve at the present

time. Palo Alto characterizes Preferred as seeking "the absolute

right to construct and operate" a cable television system, and

states that "[tJhe question is simply whether cable franchising

-7

as an institution is constitutionally sound." (Amici Br. at

3-4) Palo Alto claims that ?referred must lose this appeal so

long as Los Angeles and/or Palo Alto can describe any conceivable

"franchising process" which would be constitutional. These

statements are erroneous for several reasons.

First of all, this appeal involves a l2(b)(6)

dismissal. It is t ~ e cts alleged in the complaint, not some

imaginary cts suggested by Palo Alto or Los Angeles, which will

form the basis for this Court's decision. Contrary to Palo

Alto's assertion that Preferred has not "attacked the details of

Los Angeles' particular franchising process", the complaint

contains almost three pages of such "details" which Los Angeles

imposed as prior restraints even to participate in its auction

(at least with the chance of "winning"). (CT 1 at 8-11). At a

minimum, each of those ?rior restraints would have to be

justified (ba upon cts) before Los Angeles can prevail as a

matter of law. Palo Alto's attempt to defend some paradigm

"franchise process" must be rejected unless it is concluded that

there is no conceivable municipal action which could violate a

cable television operator's First Amendment rights.

More significantly, the complaint also alleges "that the

city will not permit plaintiff to operate a cable television

system within the South Central area under any circumstances or

on any terms and conditions." (CT 1 at 11-12). Thus, it is Los

~ ~ g e l e s ' exclusion of Preferred which must be defended in this

case. In the second half of its brief, Palo Alto suggests some

purported "governmental interest" in the availability of certain

cable services (such as access channels). However, Palo Alto

-8

fails to explain how those "interests" could support Los Angeles'

total exclusion of plaintiff.

Assuming ar endo the legitimacy of the interests

proposed by Palo Alto, the appropriate method of fulfilling those

interests would be to enact a legislative ordinance requiring the

relevant services, and then to invite in all persons willing to

operate subject to such requirements. Had Los Angeles taken

action, imposing narrow, carefully tailored requirements in a

non-discriminatory shion, Palo Alto's discussion might be of

more relevance. Perhaps, in that case, certain of those

requirements would be upheld -- perhaps not. The Court no

p

not

decide those questions because Los did not proceed in

that fashion. This Court has no way to know what requirements

Los Angel es l'Y'ould in fact impose were it to proceed properly, in

a normal legislative manner. Regardless of the opriety of the

asserted interests, the auctioning off of a First Amendment

right, and the tot3.1 and permanent exclusion of the "losers" and

"non-participarlts," is an improper method of seekirlg to achieve

those interests. As the District Judge in the Boulder case

recognized:

Assuming that Boul r does have the claimed

authority to regulate cable television within the

City in the manner which [it desires], the

approach taken is not an appropriate exercise and

articulation of a policy of regulation ... It

might well be a different case if Boulder had

enacted an ordinance articulating qualifying

criteria for cable companies to do business in

the City, with such other regulations as the City

government might believe to be ne essary and

proper in the exercise of police power ..

Community Communications Co. v. City of Boulder, 485 F.Supp.

-9

1035 (D.Colo.), rev'd 630 F.2d 704 (10th Cir. 1980), reinstated

455 U.S. 40 (1982).

Finally, this case does not turn, as Palo Alto

contends, upon "the right to operate a cable television system

without a franchi se" . Rather, the key question is: "Under

what circumstances and for what reasons may Los

withhold such a franchise?" Pref'2rred is quite willing to

obtai:"! a "franchise" (or "license", "permit", etc.) from Los

Angeles, so long as Los l-1....'1geles issues it in cOElpliance with

4

the requirements of the Constitution. For exanple, a ci

can constitutionally require a parade permit from would-be

demonstrators, but the First Anendr:1e!1t requires that such

permits be issued in a manner consonant with its dictates. The

same is true for cable television "per.nits."

III. PALO ALTO'S .!;TTE>lPT TO DEVALUE PREFERRED'S

FIRST RIGHTS, A!:'l"D THUS TO AV'JE)

CONSTITUTIONAL SCRUTIJY OF ITS

EXCLUSION, MUST FAIL

Palo Alto contends (1) that a prohibition upon the

erection of a cable television system does not raise rst

Amendment questions because the actual laying of wires does not

4 The recently enacted Cable Act defines the term

"franchise" as meaning any "authorization . whether such

authorization is designated as a franchise, permit, license,

resolution, contract, certificate, agreement, or otherwise".

(Section 602(8. This definition undercuts Palo Alto's claim

of support from the Act's explicit authority to issue

"franchises".

-10

involve expression; (2) that the

rst Amendment protects only

material, that the publication and

transmission of expression created by anyone other than an

employee of Preferred is completely unprotecte5; and (3) that,

as a result of the previous two contentions, Preferred's only

"true" First Amendnent activity (i.e., transmission of

newly-created m::lo::erial) could be "adequately" disseminated

through use of the "leased access" channels to be provided by

Los Angeles' selected cable

These ::lore The first, because

it relies upon an unacce ably narrow view of the First

Amendment; the second, because it represents a etely

improper and unprecedented view of w"'nat is "expressive

activity"; and the third, because it depends upon the accuracy

of the first two. In addition, the third proposition is

erroneous for reaS0ns.

A. The Constitution Protects The Means

Of Qisse;nination .;'s h'ell As The

Disse;nination Itself

Palo Alto argues that the construction of a cable

television system "itself involves no communication protected

by the First Amendmert ... [The] activities [involved in

erection of a cable system] are no more protected by the First

Amendment than are construction of water, electrical, or gas

distribution systems, or for that m::lotter telegraph or telephone

systems." (Amici Br. at 7). This argument is erroneous.

-11

Palo Alto is incorrect when it states

that placement of the means of conmunication (i.e. cables and

wires) upon public rights-of-way is unprotected under the First

A:nendment. Rather, when a person seeks to take some action for

the purpose of subsequent expression, such action is protected

under the First Amendment. The Constitution protects the means

of dissemination as well as the dissemination itself.

Associated Film Distribution Corp. v. Thornburgh, 520 F.Supp.

971, 982 (E.D. Pa. 1981); "'leaver v. Jordan, 64 Ca1.2d 235

(1966) As the California Supreme Court stated in Wollam v.

City of Palm Springs, 59 Ca1.2d 276, 284 (1963):

The right of free speech necessarily

embodies the means used for its dissemination

because the right is worthless in the absence of

a meaningful method of its expression. To take

the [contrary] position ... would, if carried to

its logical conclusion, eliminate the right

entirely.

As Preferred has previously noted (Appellant's Opening Br. at

13-15), this point was recognized and specifically applied to

the erection of a cable television system in the Boulder

litigation.

This point is also clearly evidenced by the "newspaper

box" cases. See, e.g., Miami Herald Pub. Co. v. City of

Hallandale, 734 F.2d 666 (11th Cir. 1984); Southern New Jersey

Newspapers v. State of Jersey, 542 F.Supp. 173 (D.N.J.

1982); Kash Enterprises, Inc. v. City of Los Angeles, 19 Cal.3d

294 (1977). These cases clearly hold that the placement of

newspaper boxes in public forums is activity protected under

-12

the rst Amend::aent. As was stated in Southern New Jersey

Newspapers, supra:

In that [newspaper] boxes playa role in the

distribution of plaintiffs' this

court agrees with the position that such devices

are entitled to full constitutional protection.

S

542 F.Supp. at 183. Were Palo Alto's contention correct, a

city would be permitted to ban a newspaper's boxes from its

streets because "they are nerely metal and plastic structures

whose placement is unrelated to actual dissemination."

B. The Re-Publicatio!1 Of .;rlOther's Views Is

Entitled To Full Constitutional Protection

Palo Alto urges upon this Court the novel proposition

that a person who "merely" re-publishes (i.e. re-transmits) the

messages of another is not entitled to any rst .:;"-c1ewJ.ment

rights. However, scrutiny of this theory reveals its untenable

nature -- it represents on what Palo Alto wishes the law to

be, not what it is.

No case of which Preferred is aware has ever

identified any such differing First Amendment protection for

5 Of course, valid time, place and manner regulations are

permissible when a speaker seeks to ce its means of

dissemination upon public property. Plaintiff has always been

willing to comply with such reasonable regulation of the manner

in which it erects its system. (CT 1 at Par. 9).

-13

.. d . . 6

orlglnate --as opposed to other-- Rather,

the case law makes clear that republication is fully as

protected as original expression. Thus, for example, motion

6

Palo Alto supports its theory with a hodge-podge of

inapposite cases. None of those cases recognize the

constitutional distinction I",hich Pal!) Alto urges upon t"!1is

Court.

Two of the cases, Fortniqhtlv Corn. v. United Artists

Television Inc., 392 U.S. Teleprompter Corp. v.

CBS, 415 U.S. 394 (1974), are t3ken out of context: they are

copyright cases, which solely addressed the issue whether the

retransmission of broadcast programs fell within the legal

de f ini t i on of "per fornances" under the Copyr i ght Act. Ne i ther

mentions the First Amendment.

The citation to United States v. Midwest V 0 Corp., 406

U.S. 649

1

680 (1972), is to the dissenting opinion.

plurality and concurring opinions in the case draw no such

distinction. More importantly, none of the opinions addressed

First Amendment issues. In Home Box Office, Inc. v. F.C.C.,

567 F.2d 9, 45 n.80 (D.C. eire ), cert. denied 434 U.S, 829

(1977), the court does not the distinction claimed by Palo

Alto, but merely to show that any permissible statutory FCC

authority over "broadcast" signals could not be used to justify

control over non-broadcast programming. Moreover, the footnote

is to a paragrap'1 which ccmcl udes that "there is nothing ... to

suggest a constitutional distinction between cable television

and newspapers ...... Id., at 46.

Finally, Palo Alto's reliance upon the six FCC cases

decided between 1965 and 1969 is unjustified. Br. at

10). Each of those cases involved the FCC's authority to

control communications disseminated over the broadcast

spectrum. Those cases simply held that the FCC could regulate

the uses made of such communications by cable companies --and

by any other persons.

Not one of these cases even arguably stands for the

proposition that original and re-published messages receive

differing First Amendment protection. Most of them did not

even mention or consider any First Amendment issues.

However, Palo Alto's reliance on these cases simply

underscores its failure to recognize the constitutionally

significant changes which have occurred in the cable television

medium, and which make modern cable television operators

directly analogous to newspaper publishers. In the 1950's and

60's, community antenna television was generally limited to

re-transmission of broadcast signalS:- Today, that simply is

not the case. See, Appellant's Opening Brief at 5-7.

-14

picture theater owners, who if ever create or edit films

that they exhibit, possess full First Ajnendment rights.

Interstate Circuit v. Dallas, 390 U.S. 676 (1968). Similarly,

book publishers and local broadcast television stations, which

generally or exclusively "republish" or "distribute" content

created by others, enjoy First Amendment protection. Bantam

Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58 (1963), v.

_E_d_u_c_a_t_i_o;;..;n'-'..-a_1C-T_eC-l..... e_v_l_s.:....;;.i..:;.o 688 F. 2 d lO 3 3 (5 t h ..... C i r.

1982)

Newspapers are also primarily composed of content not

originated by their employees. Such typical content would

include national wire service stories and photos; syndicated

news, opinion and/or entertainment columns; advertisements;

want ads, c strips; financial/stock market data; sports box

scores and averages; and theater and television schedules. Yet

these same major newspapers enjoy First Amendment protection.

See, e.g., r-1iami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo, 418 U.S.

241 (1974), Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 293

(1936).7

7 Palo Alto might argue that newspapers lish "more"

self-created material than do cable telev sion operators.

However, acceptance of such a tenuous foundation for a

constitutional princi e would not only effect a radical

re-ordering of rights, but would also open a virtual wonderland

of issues: Hhich newspapers create more material than which

cable television operators? What if a particular cable

television operator creates more new material than a particular

newspaper publisher? How much newly-created material is

(Footnote continued on next page)

-15

This Court's recent decision in Cinevision Cor. v.

City of Burbank, 745 F.2d 560 (9th Cir. 1984) completely

repudiates Palo Alto's theory. The plaintiff in Cinevision was

a concert promoter who did nothing more then arrange for

performances by various musical groups.

City suggests that because Cinevision

does not seek to "express" its views, it has no

First Amendment right to promote concerts for

profi t. However, ... [a]s a promoter of

protected musical expression, Cinevision enjoys

First rights.

* * *

[A] concert promoter, like a book seller or

theater owner, is a type "clearinghouse" for

expression.

745 F.2d at 567-68 (emphasis alter ) . One who acts as a

"clearinghouse expression" ne not even be familiar with

the content of that expression ln order to be afforded full

First Amendment protection. ld. at 568. Even accepting at

face value Palo Alto's description the functions of a cable

television operator, such a would exactly fit a

book seller, who neither creates nor edits books, nor

necessarily provides books unavailable through a competing

Footnote Continued

"enough"? Who decides? Hould a newspaper publisher lose its

First Amendment protection if it origina no material? Might

a newspaper publisher be entitled to rst protection

on some days but not on others (e.g., on Sundays, when

syndicated features and columns, puzzles, comic strips,

advertisements and want ads amount to a higher percentage of

the newspaper's content)?

-16

8

outlet. The First protects the e ession

of ideas. True origination of an idea occurs completely within

the brain of a human being. It is the distribution of that

idea, whether by the "creator" or by anyone else, which is

entitled to protection.

8 Palo Alto suggests that the rst Amendment does not

protect "duplicative" programming, that is progr3.mming also

distributed by ot"ers. (A:l1ici Br. at 10). Hith all due

respect, this proposition is absurd. A book seller does not

lose his First AmendT11ent rights simply because a conpetitor

sells the sane A movie theater cannot be closed merely

because a thea ter nearby shows the sane movies. '1'\;/0 Los

Angeles newspapers may both carry the same wire story, a:1d both

have the cO:1stitutional right to do so. One's First AInendment

rights are not lost simply because one's neighbor or competitor

says or publishes the same thing.

Palo Alto's citations are etely off point (and,

indeed, border on the bizarre). Justice Powell's concurring

opinion in Young v. &l1erican Theaters, 427 U.S. 50, 78 n.2

(1976) discusses a zoning ordinance that regulates where adult

movi es could be not whe ther they could be shown. Ti18

regulation dii not prohibit 3.ny rticular exhibitor froT11

showing movies, or limit the number of total exhibitors within

the city. In fact, Justice Powell points out that rk

forces ,.;ill determine the number of adult theaters w

city, not the zoning ordinance. Id. at 79. In United States

v. Paramount Pictures, Inc., 334 U.S. 131, 166-67 (1948), the

Supreme Court an antitrust case dealing with

monopolistic cO:1duct by private movie ?roducers. The Court

considered the "suggestion" that the monopolistic conduct at

issue might amount to a First Amendment violation of the rights

of the audience at large. The Court simply noted that the

monopolistic conduct at issue did not deny access to any

willing viewer. Finally, in Capitol Broadcasting Co. v.

Mitchell, 333 F.Supp. 582, 584 (D.D.C. 1971), ':he District

Court upheld a ban upon the broadcast of cigarette advertising

because of the limited First Amendment protection granted to

commercial speech [at least in 1971J and "the unique

characteristics "of" the broadcast medium. The Court also

noted that bro3.dc3.sters were not precluded from 3.iring their

own point of view on any aspect of the cigarette smoking

question.

In sum, it would be an understatement to say that these

cases do not support Palo Alto's claim that the First Amendment

provides no protection to a willing speaker if another speaker

has beat it to the punch.

-17

In any event, Palo Alto's characterization of a modern

cable television operator as nothing more than a passive

re-transmitter of messages is simply incorrect as a

factual matter. As the Supreme Court recognized more than five

years ago:

Cable operators now share with broadcasters a

significant amount of editorial discretion regarding

what their programming will include. As the

Commission, itself, has observed, "both in their

signal carriage decision and in connection with

origination function, cable television systems are

afforded considerable control over the content of the

progranming they provide."

FCC v. Midwest Video Corp., 440 U.S. 689, 707 (1979) (emphasis

added). This exercise of editorial discretion is fully

protected by the First Miami Herald Publishing Co.,

supra, 418 U.S. at 258.

C. P-3.lo Alt:)'s Reli-3.nce Upon "Leased

.

Access" Is Misplaced

In an argument predicated upon this Court's acceptance

of its extraordinary "republication" theory, Palo Alto claims

that Preferred's unquestioned First Amendment -3.ctivity (i.e.

dissemination of newly-created material) can be fully met by

us ing space purchased from ar'.other cable company. Therefore,

Palo Alto argues, Los Angeles is free to preclude Preferred

from erecting its own system. Since, as Preferred has already

shown, all of Preferred's programming would be protected

speech, and Palo Alto concedes that there will never be

sufficient space on the "franchised" cable operator's system

-18

available for Preferred to provide all such programming, the

Court should reject Palo Alto's on that basis alone.

However, even were this not the case, Palo Alta's claim that

"leased access" is "adequate" for Preferred is completely

erroneous.

First of ::ill, the existence of some "alternative"

method of communicating one's message does not in and of itself

entitle government to prohibit the particular preferred

by the speaker. Palo Alto's claim is similar to the claim of

the government in Bolger v. Young's Drug Products Corp., ___

u.s. 77 L.:j.2d 469 (1983). In that case, the federal

government successfully attempted to support a ban upon the

unsolicited mailing of contraceptive advertising. The Supreme

Court stated:

The GovernJClent argues that section

300l(e)(2) does nat interfere "significantly"

with free speech because the statute applies only

to unsolicited mailings and does not bar other

channels of communication .... However, this

Court has previously declared that "one is not to

have the exercise of his liberty of expression in

appropriate places abridged on the plea that it

may be exercised in some other place".

77 L.Ed.2d at 479 n.1B (citations omitted).

Secondly, the "alternative" suggestej by Palo Alta

would be woefully inadequate to meet Preferred's First

Amendment interests. Just as the First Amendment rights of a

newspaper publisher would be violated by a requirement that it

purchase space from a rival newspaper in order to disseminate,

Preferred's First Amendment rights would be severely infringed

were it rele9ated the "second class citizenship" urged by Palo

-19

Alto. The use of channel space on the system of another is a

vastly inferior of communicating to cable television

subscribers. Such a method o speech would ma

1

<;:e it impossible

to generate the revenue stream necessary to support local

9

reporting and program production. The viewers would be the

system owner's subscribers, and would pay it, not Preferred.

EVen were it possible to enter into some arrangement for

separate receipt of revenue flowing from Preferred's

programming, it would be impossible to generate the necessary

revenue to engage in the variety of communication which

Preferred desires. As with any of the media, some

lucrative services subsidize the provision of less profitable

9 Palo Alto erroneously shrugs off financial interests as

being outside the ambit of the First AmenJment, cit U.S.

Postal Service v. Council of Greenburgh Civic 453

U.S. 114 (1981). However, Palo Alto seriously misreads

Greenburgh. In that case, the Supreme Court found --contrary

to the facts of this case-- that the public property at issue

was not a public forum. The Court then simply noted that the

merearticulation of an inexpensive poss e use II'/as

insufficient to convert a non-public forum location into a

public forum. In this case, the starting point is that the

public locations in question are a public forum.

Innumerable decisions have recognized that the First

Amendment protects the financial interests of speakers. Se

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233 (1936)

(gross receipts tax): Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105,

112-14 (1943) (solicitation tax); :>1offett v. Killian, 360

F.Supp. 228, 231 (D. Conn. 1973) (fee charged for lobbying). As

the Supreme Court explained in Schaumberg v. Citizens For A

Better Environment, 444 U.S. 620 (1980), and recently

reaffirmed in Sec. of State of 'land v. J.R. Munson Co., 52

U.S.L.W. 4875 (June 26, 1984 , a restriction upon the ability

to raise revenue affects a First Amendment speaker's ability to

speak at all. UnQer Palo Alto's theory, the Los Angeles Times

could be constitutionally forbidden to charge for its

publication.

-20

journalistic endeavors. "Le3.sed access" on another's system

will never be adequate from stanjpoint, both because of

the limited available sp3.ce and because prospective listeners

to Preferred's speech would already have h3.d to subscribe to

the other cable comp3.ny's services in order to the

ability to receive Preferred's Finally,

Preferred would have nO opportunity to communicate to residents

who chose not to subscribe to the other company's services. In

sum, "leased access" might be adequate for a "backY3.rd vinco

amateur", but is certainly not adequate for the quality and

scale of production which ?referred desires to disseminate.

In addition, the inadequacy of the "leased access"

alternative is exacerbated by the questionable nature of its

availability. At best, availability is limited to the

total number of channels set aside r such use by the existing

lCJ

cable operator. An un'knQlvn nU'lber of persons other t'lan

Preferred will also desire to use some or all of this space.

Preferred may well be left with no access at all, or access

only at undesirable or ever-shifting time slots. Moreover,

since Preferred desires to compete in a substantial way with

10 Palo Alto relies heavily upon the recently enacted Cable

Communications Policy Act of 1984 ("Cable Act "), which it

claims will require provision of five channels for such use.

However, it is unclear whether this requirement is

enforceable. A similar requirement imposed by the FCC upon

cable television operators was found to be violative of the

First Midwest Video Corn. v. FCC, 571 F.2d 1025

(8th Cir. 1978) a'd on other grou;ds 440 U.S. 689 (1979).

-21

any existing cable operator, Preferred will undoubtedly

confront discrimination against it in access to and

being charged for such channel time. The recently enacted

Cable Act specifically permits, and in fact envisions, such

discrimination. Section 6l2(c). As explained in the report of

the Committee on Energy and Commerce, H.R. Rep. 98-934 (August

1, 1984) (Appendix B to A.-nici Brief), Section 612 intentionally

permits such discrimination, including price discrimination

based upon the proposed content of the speech and its estimated

impact upon the existing cable system's revenue.

section does contemplate permitting

the cable operator to establish rates, terms and

conditions whic:1 are discriminatory. is,

nothing in these provisions is intended to impose

a requirement on a cable operator that he make

available on a non-discriminatory basis, channel

capacity set aside r commercial use by

unaffiliated persons ... Thus, in establishing

price, terms and conditions pursuant to this

section, it is appropriate for a cable operator

to look to nature (but not the specific

editorial content) of the service being proposed,

how it will affect the marketing of the mix of

existing services being offered by the cable

operator to subscribers, as well as potential

market fragmentation that might be created and

any resulting impact that might have on

subscriber or advertising revenues.

11. at 51.

Palo Alto asks this Court simply to assume that

"leased access" is adequate to meet Preferred's First Amendment

needs. It does so without the Court knowing anything about

Preferred's plans and desires. In essence, Palo Alto asks the

Court to rule, as a matter of law, that it is impossible for

Preferred to intend any quantity and quality of speech which

-22

could not be adequately carried over severely limited space on

a "leased access" channel. The folly in such a claim was

revealed in the evidence provided tJ the District Court in the

Century Federal case. (See Tow Decl. [Exhibit 5J at Par.

27-33).

In the alleges a cQgnizable violation

of Preferred's First Amendment rights. The possible existence

of "leased access" does not alter this fact.

IV. PALO ALTO 'S CLJ\!'iED IN __ "1CI:W FIRST

P....'1END:1E'IT V.J\L1JES" IS ',mOLLY 'dITHOUT '1ERIT

In an argument exemplifying Palo Alto's lack of

understanding of the First fuJendment, it argues to this Court

that Los Angeles' ::lonopoly franchising scheme should be upheld

because it "enhances II First A:'"lendment values. (knici Br. at

15-18). Pa 10 Al tJ arg.les that the ex i stence of "1 eased access"

requirements S0r:1e:'10'd it "wor t:1 it" to restrict

Preferred's First rights. This is purportedly

because leased access permits dissemination over a cable

television syster:1 at a lower cost to some individual members of

the public than the actual cost to society of doing so. (In

other words, that the "franchised" cable system's subscribers

are subsidizing speech over the access channels). In

Preferred's opinion, it is difficult to imagine a more wrong

headed view of the First Al'"lendment.

The fundamental doctrine of the First Amendment is

that it is not government's role to manage the marketplace of

ideas, nor to impose its opinion about the "best" manner,

-23

method or frequency of speech, nor to make judgments based upon

fears or that certain instances of speech will not

be "in the public interest". In essence, Palo Alto argues that

government is permitted to stop one class of society from

speaking (i.e. that set of persons with the resources and

ability to erect their own cable television systems) in order

to make speech by another segment of society (i.e. those

without the resources --or desire-- to own their own system)

less expensive. Needless to say, Palo Alto has things

backwards.

[TJhe concept that may restrict

the speech of some elements of our society in

order to the relative voice of others is

wholly foreign to the First Amendment.

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1, 48-49 (1976).

Palo Alto's flies full in the face of the

Supreme Court's opinion in Miami Herald Publishing Co. v.

Tornillo, 418 U.S. 241 (1974). In Tornillo, the Supreme Court

squarely rejected the concept that government could require

newspapers to provide access to the public for a "right to

reply" The Court helj that the goals of broad access and

balanced coverage of issues, however desirable, were simply

irrelevant: the First precludes government from

achieving such goals by burdening the speech of others. 418

U.S. at 254. The Court rejected the claim that there is an

exception to this rule \vhen a "natural monopoly" is present.

In this case, Palo Alto does not even posit any

exception to the rule explained in Tornillo. It simply ignores

-24

the rule and boldly argues that "good goals" provide government

11

with carte blanche to take unlimited action.

But the list of good "objectives" conceivable by

the numerous regulatory agencies of the Federal

government and perhaps achievable if they had carte

blanche, is endless. And every act of every agency

would be justified, jurisdictionally sound, and

judicially approved, if values sought were the sole

criteria.

Midwest Video Corp. v. FCC, 571 F.2d 1025, 1042 (8th Cir.

1978), aff'd 440 U.S. 689 (1979).

In any event, Palo Alto wholly fails to connect its

"interest" to the restriction at issue: The exclusion of

Preferred from willing listeners. Preferred desires to expand

the number of speakers. It desires to and intends to provide

speech different than that of any other cable television

economic self-interest provides an incentive for such

differentiation. As noted supra, the City of Los Angeles is

free to pass a generic law requiring the provision of leased

11 As was demonstrated to the District Court in the Century

Federal case, the auctioning off to a monopolist of the

opportunity to speak seriously injures First Amendment values,

not enhances them. (Lee Decl. [Exhibit 6J). The lacrc of press

freedom resulting from the selection and subsequent control

over a member of the press makes it impossible for the press to

fulfill its role as watchdogs over government. As Justice

Stevens commented in a recent First Amendment case:

The court jester who mocks the King must choose

words with great care. An artist is likely to paint a

flattering portrait of his patron. The child who

wants a new toy does not preface his request with a

comment on how fat his mother is.

FCC v. League of ivor:1en Voters, U.S. 52 U.S.L.H. 5008,

5020 (July 2, 1984) (dissenting opinion).

-25

access channels by cable television operators and then to

permit Preferred, and others, to operate subject to such

requirements. Such non-discriminatory, generic regulations

could then be scrutinized by a court to test their

constitutionality. It is only at that point that Palo Alto's

arguments about "enhancement" woul] be properly before the

Court and ripe for assessment.

V. Pl".LO ALTO AND

THE O'BRIEN TEST

In the second half of its brief, Palo Alto argues that

Los Angeles' actions, even if they do infringe upon Preferred's

First Amendment interests, are justified under the balancing

test set forth in United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367

(1968). However, Palo Alto is wrong -- the O'Brien test does

not apply in the context of this case. Furthermore, even were

the First Amendment infringements at issue here assessed under

the O'Brien standards, they would fail to meet those

requirements.

A. The O'Brien Test Does Not Apply

To The Facts At Issue

Palo Alto summarily asserts "[bJecause the franchise

process is content neutral, the 'track two' test [of Professor

TribeJ, derived from United States v. O'Brien ... applies."

(Amici Br. at 21).

However, even assuming Palo Alto were

correct that Los Angeles' franchising process had been content

-26

12

neutral, that is not the correct test for determining

whether O'Brien applies. Rather, the O'Brien test applies only

where "speech" and "non-speech" elements are combined in the

same course of conduct and government wishes to regulate

"non-speech" aspects for a purpose unrelated to communication.

u.s. v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. at 376-77. Unless the governmental

regulation in question is aimed at the non-communicative

aspects of an action, it is unconstitutional absent a showing

of a "clear and present danger" or equivalent concern. Palo

Alto's own quotation from Professor Tribe establishes this

12 Preferred vigorously contends that Los auction

process was in fact content-based. A review of Los Angeles'

RFP documents (which, of course, Preferred was not even

permitted the opportunity to bring before the District Court

because itR case was dismissed on a Rule 12(b)(6) motion) would

reveal a whole host of questions and requests for information

about the "proposed programming" of the bidders. In fact, the

final "franchise ordinance" contains specific requirements that

Los Angeles' selected operator provide particular 9rO]ramming

on particular channels. (Exhibit D to Palo Alto's Brief at

9-10). By the very nature of a process which places government

in the role of deciding who shall speak, content-based

decisions are almost inevitable. The RFP process acts in part

as a screening device, permitting government to make subjective

and unreviewable decisions based upon philosophy and

viewpoint. For example, it is not likely that Los Angeles

would have ultimately selected a company owned by individuals

had long publ i cly demanded the ous ter of the Hayor and the

City Council members (or an individual who believed that sports

should be seen in person and not on television, or one who

believed in limiting television to non-violent programming).

By putting itself in the position of asking about and selecting

between programming proposals, Los Angeles insured that it

would make a content-based choice. The problem is fundamental

--government should not be choosing at all. Tow Decl.

[Appendix 5J at par. 34-447 Lee Decl. [Appendix 6J at par.

30-49.

-27

point. ( i\i1 Lei B r. t 1 <1 - 2 0)

The Supreme Court :--tas evolved bol:")1isti.:lct'l.ppro7:'1ches

to the resolution of first amendment claims: two

correspond to the two ways in v.fhich government may

'abridge' speech. If a government regulation is aimed

at the communicative impact of an act, analysis should

proceed along what we will call track one. On that

track, a regulation is unconstitutional unless

governnent shows that the message being suppressed

poses a 'clear and present danger,' a

falsehood, or otherwise falls on the

llnprotected sieie of one of 1i :l',H ;:11:! ::::nrt has

drawn to distinguish those expressive acts privilege,1

by the i t"st. rl.lendnent from tflC)se t:) :F)vernment

regulation with only minimal due process scrutiny. If

a government regulation is aimed at the

noncommunicative impact of an act, its analysis

proceeds on what we will call track two.

Tribe, American Constitutional Law at 582. As the Supreme

Court recently made clear, Tribe is correct on this

point:

[GJovernment has legitimate interests in

controlling the non-communicative aspects of the

medium, Kovacs v Cooper, but the Fi r s tt'11

Fourtee;"1.th AJ-;1enlments- tor(3close a Si.1U.,"-J

interest in controlling the communicative

aspect3.

Metromedia, Inc. v. San Diego, 453 U.S. 490, 502 (1981)

(plurality op'n.). As is discussed more fully below, the

interests which Palo Alto asserts are directed toward

"controlling the communication aspects."

This is not a case about illegal conduct. It does not

involve illegal draftcard burning (O'Brien), nor does it

concern the conduct of illegally sleeping in a Park

(Clark v. Community For Creative Non-Violence,

U.S.

- 2:1

posting of signs on non-public forum utility poles (City

Council of Los Angeles v. Taxpayers For Vincent, u.s.

52 U.S.L.N. 4594 (.'-1ay 15, 1984)). Those were all acts which no

one was allowed to do. In each of those cases, the conduct in

question was illegal for anyone and everyone. In contrast, the

placement of wires in public rights-of-way is not illegal for

everyone: public utilities do it, the city's "franchised"

cable company does it, and very probably many others do it

after they secure the normal encroachment permits which

Preferred has requested but been denied. Put simply, Los

Angeles has made the "conduct" in which Preferred wishes to

engage (the placement of wires in public rights-of-way) illegal

because and only because Pre ferred 'II i shes to di s seminate

'h . 13

througn t ose WIres.

The opinion in O'Brien itself establishes that this

case is not a proper one for application of the balarcing test,

and that Los Angeles' actions are unconstitutional.

The case at bar is therefore unlike one

where the alleged governmental interest in

regulating conduct arises in some measure because

the communication allegedly integral to the

conduct is itself thought to be harmful.

was 391 U.S. at 382. The Court then distinguished Stromberg v.

13 This fact is evidenced effectively by Palo Alto's list of

"interests" which it presents on behalf of Los Angeles. Except

for interes t "No. 5", each of those II interes ts II relatas

directly to the quantity and/or quality of speech provided by

cable companies. Only No.5 has anything to do with the

non-communicative aspects of the conduct in question.

-29

California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931), "since the statute there was

at suppressing communication, it could not be sustained

as a regulation of non-communicati ve conduct." As a of

Palo Alto's "interests" establishes, at least in its opinion

Los Angeles trying to "suppress" communication because the

communication would be "harmful" (i.e. by adversely affecting

Los Angeles' ability to extract concessions from its selected

monopolist).

In summary, tne test utilized for incidental

infringements upon First Amendment speech-- unrelated to free

expression-- does not apply to this case. Absent some reason

for altering First Amendment standards --such as applies in the

broadcasting area-- Los Angeles' actions towards Preferred

cannot be justified any more than they could be if applied to a

newspaper publisher. Ne i ther Los A!1gel es nor !?alo Al t'J prov ide

any reason for altering those standards.

B. The of the O'Brien

Test Are Not

Even if the O'Brien test did represent correct

standard under which to assess Los Angeles' restrictions upon

Preferred's First rights, those standards have not

been met.

1. It Is Los Angeles' Interest

Not Palo Alto's Guesses About

Them, '.f'lic'1 '.lust he Ijenti fied

Palo Alto lists five "governmental interests", which

-30

it argues are served by "franchising". However, there is

nothing in the record before this Court, or before the court

below, to indicate whether any or all of these "interests" were

sought to be furthered by Los eles in taking the alleged

- - - ~ ' - - - -

actions. Interests asserted as justifications for

infringements upon speech must be "carefully scrutinized to

determine if they are only a public rationalization of an

impermissible purpose." Metromedia, Inc. v. San Diego, supra,

453 U.S. at 510. In this case, the Court obviously has no way

to know what relevance, if any, Palo Alto's asserted interests

have in the context of this case. To accept such an interest

without any indication that it is in fact an interest of Los

Angeles, would be to invite acceptance of mere "public

ra t ional i za t ions." Since Los Angeles, i tsel f, has never

presented the Court with its proposed justifications, Preferred

submits that the Court has no relevant interest before it to

assess.

2. Palo Alto's Suggested "Interests"

Are Improper

One of the requirements of the O'Brien test is that

"the governmental interest [be] unrelated to the suppression of

free expression."

391 U.S. at 377. As noted above, four out

of the five interests suggested by Palo Alto are directly

related to expression, and hence are improper interest in the

first place.

Despite Palo Alto's (and presumably Los Angeles'

ins i s tence that it cr)uld "do bet ter" than the free marketplace

of ideas, the First Amendment forbids this kind of

-31

interference. It is not a proper governmental goal to try to

"do better". Attempts to "manage" a medium of expression are,

quite simply, beyond the proper police power of a municipality.

3. "Cream Skimming II

Palo Alto contends that there is some

governmental interest in insuring that a cable television

company which offers to serve any customer within a certain

area (as determined by Los Angeles) will offer to serve every

resident within that area. There are several problems with

this suggestion. First, Palo Alto simply assumes that by

terming a goal a "policy objective" it is entitled to obtain

it. Yet cable television is not a public utility and does not

provide an essential service. Television Transmission v. Pub.

Util. Com., 47 Cal.2d 82 (1956). An attempt to compel service

to all areas, regardless of cost, is therefore

unconstitutional. Frost v. Railroad Commission of California,

271 U.S. 573, 583 (1926); Video Corp. v. F.C.C., supra,

571 F.2d at 1051. See, Cox Cable Communicatio:1s, Inc. v.

Simpson, 569 F.2d 507, 518-519 (D.Neb. 1983). To the extent

(if any) that such a requirement could be upheld as a

reasonable regulation of a monopolist, Palo Alto implicitly

relies upon the natural monopoly theory which it admits is

unproven.

Second, even assuming arguendo that such a requirement

is otherwise within Los Angeles' power, Palo Alto suggests no

reason why a less onerous alternative is not available. Los

-32

Angeles could simply pass an ordinance requiring universal

service. By so doing, Los Angeles would insure that any cable

television operating within the South Central area

would offer service to all residents thereof. This procedure

\vould fulfill this purported interest even better than a

monopolistic franchising process, because would be

provided a choice between different companies.

Third, there is no indication on this record that

Preferred would be unwilling to offer service to every resident

within the South Central area. Preferred is, in fact, not only

willing but anxious to do so, and would already be providing

such service were it not for Los Angeles' refusal to permit

it. Even accepting Palo Alto's superficial description of

cable television economics (Amici Br. at 22-24), any reasonable

analysis of the possibility that "cream skimming" would occur

must of necessity include the particular characteristics of the

market at issue. A sinilar argument made by Palo Alto in the

Century Federal case was totally repudiated based upon the

facts in that market. Tow Decl. [Appendix 5J at Par. 13-19.

Finally, Palo Alto insufficiently identifies any nexus

between this policy "interest" and the exclusion of Preferred.

Los Angeles already has a commitment from a cable company to

provide service throughout the relevant area. Therefore, even

if Preferred did not serve all areas, every resident would have

access to at least one company. Palo Alto's only suggestion

otherwise is a return to the natural monopoly theory which it

claims not to rely on. (Amici Br. at 28).

-33

4. Access Channels

process as related a interest in obtaining

access channels. Again, the only asserted nexus between this

interest and Preferred's exclusion is the unproven suggestion

that cable television is a natural monopoly. Los Angeles has

already obtained access channels from one cable television

operator. Therefore, Los Angeles' interest in this regard has

already been fulfilled.

As in the case of "cream skimming", the proper method

for Los Arlgeles t:') furt:ler an interest in obtaining access

channels would be to pass a :')rdinance requiring t11em.

Preferred believes that any such requirement would be

unconstitutional. Hiami Herald Publis'Ling Co. v. '1'0 1::' "1 i 110, 418

u.s. 241 (1974) 7 Midwest Video Corp, v. F.C.C., supra, 571 F.2d

14

at 1052-57. As discussed above in Section IV, i:1j'-1ry to

Preferrei's ric)'lts Cd'1f1.)t be jclstified by the expansion of

someone e1 I s

14 L.:11icated some willingness

(erroneously, Preferred submits) to accept such control over

programmi:1g (see, e.g., Community Communications Co. v.

Boulder, 660 F.2d 1370 (10th Cir. 1981)), have required

government to first establish that economic scarcity made such

control a nec2ssity. Here, Palo Alto does not rely on

economic scarcitJ.

-1't

require this Court to hold that the Los Times could

constitutionally be given a government-guaranteed monopoly

within Los Angeles County so long as it agreed to permit the

public free access to a few pages of the paper.

Finally, even assuming that the obtaining of access

is a proper governmental goal, the obviously less

onerous alternative available to Las would be to spend

15

public money in order obtain that "public good." Though

the City may have a valid interest in raising revenue (or

reducing expenditures), it may not do so by inordinately

burdening First Amendment speakers. Minneapolis Star v.

Minnesota Commissioner of Revenue, U.S. , 75 L. Ed 2d 295

(1983); Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233 (1936).

In essence, Palo Alto argues that Preferred should be excluded

in order to finance public access channels that neither the

City nor the public are will ing to pay for.

6. Computer-to-Computer Data

Palo Alto suggests that Preferred's exclusion could be

justified by the "percieved risk" that certain computer-to-

Palo Alto's argument essentially boils down to

the follo',dng: "By excluding Preferred and all other

cable television operators, Los can guarantee a

monopoly to one selected person. Since that person will

then make monopoly profits, he will agree to give some of

those profits to the City or to the public in exchange for

protection from competition. This will save the City

money. "

-35

15

computer data transmission services will not develop "quickly

enough." (Amici Br. at 26). Preferred could hardly have

imagined a better illustration of Palo Alto's misunderstanding

of the First Amendment. Palo Alto simply identifies something

it thinks would be "nice", states that a city will "forfeit the

necessary to obtain" (ld. at 29) this nice thing unless it

provides a government protected monopoly to one selected

speaker, and then argues that the First permits the

exclusion of all speakers but one because of the policy

objective of "getting something nice". This exact argument

could be made in support of the monopolization of any medium of

speech. A bookseller might well

be willing to subsidize a free lending library for the poor; a

government-sanctioned monopoly movie theater might well admit

senior citizens at 75% off regular ticket prices; and a

government-franchised newspaper would certainly be willing to

provide free guest column space for the Mayor and City

Councilmembers. Under Palo Alto's theory of the First

Amendment, no content-neutral burden upon free speech would

ever be held unconstitutional unless it was completely

irrational and arbitrary.

Each of the objections described in the preceeding two

subsections also apply with full for2e to Palo Alto's claimed

interest in data transmission. There is no proper nexus

between Preferred's exclusion and the interest sought; there is

no reason why a generic, non-discriminatory ordinance could not

fulfill the purported interest; and this interest could

properly be met in a less restrictive fashion by the direct

-36

purchase or subsidization of such services. Furthermore, the

provision of most data transmission services by a cable

television op,=r3.t)( i.s \vithin the State of California.

Cal. Public Utility Commission Decision No. 84-06-113 (June 13,

1984) In addition, a municipality's attempts to force upon a

cable television operator the provision of such common carrier

functions amounts to an unconstitutional taking violative of

the Fifth Amendment. Frost, Video, Cox Cable, all

supra.

7. DisruptlQn of 5-")f-;lay

Lastly, Palo Alto asserts that Los Angeles has an

interest in minimizing disruption of its rights-of-way. This

is undoubtedly true, and in fact amounts to the only

non-expression related interest proposed by Palo Alto.

H042ver, Palo Alto seriously misunderstands the significance of

this interest :tn1 ,-=xtent to whic''1 Pi rst A:nendment

permits reliance upon it to b'-.lxden free speech. Hhat Palo Alto

fails to ,:'L1:: .1,l')i,-i,,; ':) ,,'11:::'1

Preferred desires access are a "public orc1u for

communication". Cinevision Corp., supra, 745 F.2d at 569-71.

In Perry Education Assn. v. Perry Local Educators'

Assn., 460 U.S. 37, 44 (1983), the Supreme Court described

three types of public forums, with accompanying public access

rights ti1at vary "depending on the character of the property at

issue." The first category includes areas such as streets and

parks, "which by long tradition or by government fiat have been

-37

devoted to assembly and debate." ld. at 45. The second

category includes public property, such as municipal

auditoriums, which, though not traditionally used r a

particular type of communicative activity, have been

for use by the public as a place for SUC:1 "tel: -.Ii ty.

44-45; Cinevision Corp., supra, 745 F.2d at 569-71. The third

category of public property is that "Hhich is not by tradition

or designation a forum for public communication." ld. The

identical broad free speech rights apply to communication in

either of the first tHO categories, Cinevision Corp. at

16

570_71.

property within either the first or second categories of public

forums, this Court need not decide cv

1

11c:h 1:1c1udes t:1e

public rights-of-way at issue in this case. There can be no

real doubt the Los fu:1geles has designated those rights-of-way

for use by cable television communicators; it has already gone

. 17

so far as to grant permission to one such communlcator,

16

EV2a in thO'! third cate9:Jry,vhic:l includes SUC

1

1

property as county jails v. Florida, 385 U.S. 39

(1966)) and military bases (Unit3d v. 710

F.2d 1410 (9th Cir. 1983)) the government is limited to

"reasonable" regulations designed to reserve the property for

its intended use. Cinevision Corp., supra at 569-70 n.8.

17 It is irrelevant that L:::>s may 11ave "intended

(Le. desire1) t:1d.t the public rights-o:-vfay be us by o:11y

one cable television operator. Cinevision Corp., supra at

570. (City permission, even though only to a single entity, to

(Footnote continued on next page)

-38

thus the compatibility of such use. Grayned v.

City of Rockford, 408 U.S. 104, 116 (1972). In addition, the

Cal i fornia Legi s lature has "opened" the forull 0 f publ ic uti 1 i ty

b.cili ties for ;13e by ca1;le television operators allover the

State, by Cal.Pub.Util. Code Section 767.5, which

declares that such use is the consumption of a "public utility

California". ( S u bd . ( b) ) In short, at least until Los

Angeles and the State of California withdraw those

rights-of-way from use by the public, they remain a public

forum for use by cable television operators.

The rules governing access to public forums is that:

II [G]overnment fnay '10:' prohibit all

communicative activity. For the state to enforce

3. content-basei 8xcl:..13iYl it ,,'lS!: it'l

regulation is f18c''!')?1. ... I t:) :';'3rve a compelling

state interest and that it Ls narrowly irawn to

achieve that end. The state may also

enforce regulations of the time, place, and

,Ud:lrlf3C ;)f expression \-Jhich are

1Xe narrc:Mly t'3.il')"Ce"1 ::) .. ';_]"'1:

government interest, and leave open

alternative channels of communication."

Moreover, in formulating a content-based or a

time, place, and manner regulation, government

must select the means of furthering its interest

that is least restrictive of First

rights.

Footnote continued)

communicate to tiV3 public, transformed public rty int;) .3.

public forum for .:;!CprI3ssive ,'3.ctivity). The thrust of the

public forum doctrine is precisely that governments are not

permitted tG differentiate between different members rJ:(

segments of:

-'3'1

including the public rights-of-way, than those imposed by other

First Amendment speakers.

It

(CT 1 at Par. 6).19 This

allegation must be accepted as true at this stage in the

pleadings. Moreover, such a concept makes

newspaper vending boxes on public rights-af-way

permanently restricts p31estrian traffic, invites litter

problems and entails repeated traffic disruption every morning

when a truc'<:: stops toee U 11 tht=ll.

television wires are indistinguishable from each other and

the various utility facilities adjacent to them7 installed

cables are virtually maintenance-free.

A::;lib reference to "mi:<imizing disruption" is, quite

simply, legally insufficient to enforce the total exclusion of

a particular speaker.

"in excuse to li.:1it to 'Joe the number of news!)i'l.pers/

insist upon controlling the "monopolist" that it had itse1.::

crea ted) .

disruption.