Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

2012 04 20 Memo in Oppn To PI

Enviado por

capitolcurrentsTítulo original

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

2012 04 20 Memo in Oppn To PI

Enviado por

capitolcurrentsDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

Brent H. Hall, Oregon State Bar No. 992762 brenthall@ctuir.

com Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation 46411 Timine Way Pendleton, OR 97801 TEL: (541) 429-7407 FAX: (541) 429-7407 Attorney for Amicus Curiae Applicant: Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Thomas A. Zeilman, WSBA # 28470 tzeilman@qwestoffice.net Law Offices of Thomas Zeilman 402 E. Yakima Avenue Ste. 710 Yakima, WA 98901 TEL: (509) 575-1500 FAX: (509) 575-1227 Attorney for Amicus Curiae Applicant: Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation John W. Ogan, Oregon State Bar No. 06594 jwo@karnopp.com KARNOPP PETERSEN LLP 1201 N.W. Wall Street, Suite 300 Bend, Oregon 97701-1957 TEL: (541) 382-3011 FAX: (541) 383-3073 Attorney for Amicus Curiae Applicant: Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF OREGON

HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES; WILD FISH CONSERVANCY; BEATHANIE ODRISCOLL; and ANDREA KOZIL, Plaintiffs,

Case No. 12-CV-00642-SI

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

v. JOHN E. BRYSON, in his official capacity as Secretary of the U.S. Department of Commerce; SAMUEL RAUCH, in his official capacity as Assistant Administrator, NOAA Fisheries; JAMES LECKY, in his official capacity as Director, Office of Protected Resources, NOAA Fisheries, Defendants, and STATE OF WASHINGTON, by and through its Department of Fish and Wildlife, and STATE OF OREGON, by and through its Department of Fish and Wildlife, Intervenor-Defendants.

MEMORANDUM OF APPLICANTS FOR AMICI UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

I.

INTRODUCTION

Plaintiffs entire argument rests upon a faulty construct. They take a small sliver of sea lion predation in the Columbia River, that which occurs only within the mile observation area of Bonneville Dam, and then shut their eyes and cover their ears to sea lion predation in the rest of the River, which is an order of magnitude larger. Plaintiffs then compare that sliver of predation against harvest that occurs throughout the entire River and cry Foul! Look, the impacts of sea lion predation are not significant as compared to fishery harvest. Because Plaintiffs are using different denominators in their equation a specific mile boundary area vs. hundreds of river miles the full story of sea lion predation and associated harms is not found in Plaintiffs arguments. These Columbia River Treaty Tribes believe the proper inquiry should focus on sea lion predation on natural origin fish listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) throughout all MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 2

146 miles of the lower River, and then compare that with harvest in the same geographic region. Only then are the denominators in the equation aligned, and only then can an informed conclusion on significant impacts and harms be made. For the only conclusion that can be made, once the totality of sea lion predation on listed fish is measured, is that predation and the harms it causes greatly exceeds that of status quo harvest. Plaintiffs also ignore the fact that fisheries are managed under the jurisdiction of federal courts pursuant to court orders, constitutionally protected treaty rights, and federal mitigation obligations that weave together and form the backdrop for tribal and non-tribal harvest. For these and the other points and authorities discussed below, the Motion for Preliminary Injunction should be denied. II. POINTS AND AUTHORITIES

A. CALIFORNIA SEA LION PREDATION IS AN ORDER OF MAGNITUDE LARGER THAN CLAIMED Plaintiffs briefs and Complaint are littered with California sea lion (CSL) predation estimates, all between 0.4 and 4.2 percent of the salmon run, depending on the year. These numbers, however, come from a very small area: the mile observation area adjacent to Bonneville Dam. The limited geography of this area is clearly depicted by the shaded area in the inset in the map below: \\\ \\\ \\\ \\\ \\\ MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

Figure 1: Lower Columbia River and US Army Corps Observation Area

The CSL predation cited by the Plaintiffs is limited to that occurring only within a few hundred yards of Bonneville Dam, and does not reflect predation throughout the river. A better contextual measure of CSL predation is between 7 and 18% of the run of natural origin spring Chinook salmon listed under the ESA 1. The explanation for this expanded measure is provided in paragraphs 2 through 13 of the Declaration of Douglas R. Hatch, filed with this Response, and discussed further below. Mr. Hatch is a Senior Fisheries Scientist at the Columbia River InterTribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) 2. His duties include directing the CRITFC sea lion hazing

While the ESA listing for Upper Columbia River spring Chinook and Snake River spring/summer Chinook include fish produced in hatcheries, we focus on the natural origin or wild non-adipose fin clipped component of the runs as they are the critical stocks. Accordingly, any reference to ESA listed or listed fish in this Response refers to the non-adipose clipped component of the run. 2 CRITFC provides fisheries technical and policy services to the four federally recognized Indian tribes that founded the organization and govern its affairs, the Yakama, Warm Springs, Umatilla and Nez Perce tribes.

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

and predation projects implemented pursuant to the Columbia Basin Fish Accords with the Bonneville Power Administration, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Bureau of Reclamation. Declaration of Douglas R. Hatch 1-2 (Hatch Dec.). As Mr. Hatch explains, the shaded areas of the inset of the map above depict the observation area where the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers documents sea lion abundance and predation near the dam. This is the only program that systematically documents sea lion impacts, not because it is the only place where sea lion impacts occur, but because it is the only location where such a program of observation is funded. Hatch Dec. 4. Mr. Hatch leads hazing project activities that extend five miles below Bonneville Dam. In the course of those hazing activities, Mr. Hatch and his staff observe and record instances of sea lion predation that are incidentally observed during these hazing actions. Based on these observations, Mr. Hatch believes that a conservative measure of sea lion predation on salmonids in the area five miles below the dam is equivalent to or greater than the predation that occurs in the mile observation area. Hatch Dec. 5-7, 11. Thus, Mr. Hatch believes that a conservative measure of the CSL predation within both the observation area and the downstream five mile stretch of river is double the number of salmon taken in the observation area. Hatch Dec. 11. This number still does not account for the sea lion predation that occurs in the remaining stretch of 140 miles downstream to the river mouth. Mr. Hatch agrees with the 2008 bioenergetics assessment of Mr. Robin Brown, an Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife biologist, that for an average run of returning adults, there would be another 6 10% of the spring Chinook salmon run that would fall prey to sea lion predation in that 140 stretch of the river. Hatch Dec. 5, 12 and Attachment 2 to Hatch Dec., Affidavit of Robin Brown entered in U.S. District Court No. 08-cv-0347, (D.Or.). This measure MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 5

is based on the number of sea lions in the lower river (conservatively estimated at 300-500) during the salmon migration, and the number of fish they eat per day. Id. Thus, the total measure of CSL predation in the lower River will be the sum of the predation that occurs in the following three areas: mile observation area + 5 mile hazing area + lower 140 miles of River.

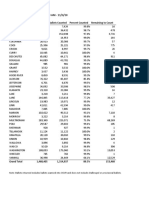

Hatch Dec. 9. CSL predation for the last ten years is displayed in the table below in terms of predation on the run component most critical to the decline or recovery of the species, the natural origin ESA listed stocks. Table 2. California Sea Lion Predation on ESA Listed Spring Chinook Throughout the Lower Columbia River.

River mouth Run Sizes A B C D E California Sea lion Take of ESA Listed Chinook Salmon F G H I Total estimated CSL ESAlisted salmon predation from river mouth to Bonneville 3,726 4,356 3,516 3,111 2,815 2,042 3,890 3,059 3,743 2,774 J % Total estimated CSL ESAlisted salmon predation from river mouth to Bonneville 6.7% 8.1% 9.8% 16.8% 15.4% 18.4% 15.6% 14.2% 9.8% 8.2%

Year 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Total/ Mean

River Mouth Run 335,214 242,605 221,675 106,911 132,583 86,247 178,629 169,296 315,345 221,157

Total wild (Listed) 55,534 53,483 35,941 18,516 18,276 11,098 24,935 21,539 38,189 33,824

% Listed 16.6% 22.0% 16.2% 17.3% 13.8% 12.9% 14.0% 12.7% 12.1% 15.3%

% CSL predation in the observation area at Bonn. 0.4% 1.1% 1.9% 3.4% 2.7% 4.2% 2.8% 2.1% 1.9% 1.1%

CSL predation in the observation area at Bonn. 197 574 680 630 493 466 698 452 726 372

CSL predation in hazing area 197 574 680 630 493 466 698 452 726 372

6% or 10% CSL predation in the lower river 3,332 3,209 2,156 1,852 1,828 1,110 2,494 2,154 2,291 2,029

2,009,662

311,336

15.3%

1.7%

5,288

5,288

22,455

33,030

10.6%

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

For each year, Table 2 3 shows the river mouth run size, and the ESA listed component of that run, both in actual fish and as a percentage of the run. The table then shows the CSL predation in the observation area, the five mile hazing area (assumed to be equal to that in the hazing area, as discussed above) and in the rest of the lower river. The calculation of predation in the rest of the lower River is either 6% or 10% of the listed fish, depending on whether that specific years run is above or below the ten year average of 200,000. 4 The resulting numbers reveal that over the last ten years, CSL predation averaged almost 11% of the spring Chinook run, and for the five lowest run sizes, CSL predation was between 14.2 and 18.4 % of the listed run. Hatch Dec. 13, Table 2. B. A MORE ACCURATE COMPARISON REVEALS PREDATION IS AT LEAST FIVE TIMES GREATER THAN HARVEST A more realistic apples to apples comparison of CSL predation to harvest numbers can be made using the measure of predation provided by Mr. Hatch. Table 3 of Mr. Hatchs Declaration, reproduced below, compares the amount of ESA listed fish eaten by CSLs with the number of listed fish harvested, in total numbers and percentages, for the entire lower River. This analysis aligns the geographic denominators and focuses on the most critical stock component, the natural origin fish. The first four columns of the table depict the year, the river mouth run size, the ESA listed component, and the percentage of the run the ESA component represents. The next four columns compare the fishery harvest in Zones 1-5 with the CSL predation in that same area, using the numbers developed by Mr. Hatch in the previous table.

There is no Table 1 in this Memorandum. We use the Table 2 term for consistency and ease of use, as that is what the table is labeled in Mr. Hatchs Declaration. 4 Mr. Hatch walks through a detailed explanation of these calculations, including the selection criteria for using 6% or 10%, at paragraphs 9-13 of his Declaration.

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

Table 3. Comparison of harvest vs. California sea lion predation.

Year River mouth Run Sizes River Total % Mouth wild Listed Run (Listed) Harvest / California Sea lion Take of ESA Listed Chinook Salmon Zone 1-5 % Zone 1-5 Total estimated % Total estimated ESA ESA CSL ESA-listed CSL ESA-listed Harvest Harvest salmon predation salmon predation from river mouth from river mouth to Bonneville to Bonneville 925 815 697 291 238 121 609 617 1,283 765 6,362 1.7% 1.5% 1.9% 1.6% 1.3% 1.1% 2.4% 2.9% 3.4% 2.3% 2.0% 3,726 4,356 3,516 3,111 2,815 2,042 3,890 3,059 3,743 2,774 33,030 6.7% 8.1% 9.8% 16.8% 15.4% 18.4% 15.6% 14.2% 9.8% 8.2% 10.6%

2002 335,214 2003 242,605 2004 221,675 2005 106,911 2006 132,583 2007 86,247 2008 178,629 2009 169,296 2010 315,345 2011 221,157 Total 2,009,662

55,534 53,483 35,941 18,516 18,276 11,098 24,935 21,539 38,189 33,824 311,336

16.6% 22.0% 16.2% 17.3% 13.8% 12.9% 14.0% 12.7% 12.1% 15.3% 15.3%

Over the last ten years, the river mouth Chinook salmon run size averaged approximately 200,000 fish per year. The ESA listed component averaged approximately 31,000 each year. Total lower River harvest (treaty and non-treaty) on listed Chinook salmon ranged from 121 to 1,283 fish, and averaged 2.0% over the 10 years. Lower River CSL predation of listed Chinook salmon, by comparison, ranged from 2,042 to 4,356 fish, and averaged 10.6% over the 10 years. In other words, the CSL predation on listed fish averaged more than five times the harvest in the lower River. Hatch Dec. 14. This contrast is all the more apparent in Figure 2, below. \\\ \\\ \\\ Figure 2. Lower Columbia River harvest, California sea lion predation, and Columbia River mouth abundance of natural origin ESA-listed spring Chinook salmon from 2002 through 2011. MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 8

The pink line represents harvest of listed fish, and the green line represents CSL predation, by year. It is noteworthy that the highest harvest as a percentage of the run, 3.4%, occurred on one of the largest runs, in 2010. The highest CSL predation as a percentage of the run, 18.4 %, occurred on the smallest run over the last ten years, in 2007. In that same year, harvest was only 1.1%. As Mr. Hatch observes, [t]his demonstrates the vulnerability of ESA-listed Chinook salmon to uncontrolled CSL take, particularly during low run years. Hatch Dec. 14. Displayed another way, in the lowest run year of 2007, the fishery accounted for 121 ESA listed fish taken in the entire lower River. That same year, however, the CSLs killed 466 ESA listed fish within mile of Bonneville Dam. That means that in 2007 CSL predation of ESA listed Chinook within a mile of Bonneville Dam not accounting for the rest of the lower River MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 9

was nearly 4 times the harvest on listed Chinook in the entire lower River. When you take into account the rest of the CSL predation that year, the number jumps to 2,042 listed fish, out of a total listed return of only 11,098. C. CALIFORNIA SEA LION PREDATION IMPACTS ARE GREATER IN THE EARLY RUN, AND DISPROPORTIONATELY HARM TRIBES. Every year during April there are many days when the sea lion predation on salmon occurring in the mile observation area alone exceeds the Bonneville Dam ladder counts of salmon. This results in a disproportionate impact on the Chinook stocks that return early, due to simple density effects. When there are less fish and they are of the same stock then more of that stock is going to be eaten. Studies from 2007 through 2010 indicate that upper Columbia River spring Chinook salmon return during the early part of run, making them more vulnerable to sea lion impacts. Hatch Dec. 15-16; Declaration of Stuart R. Ellis 14-15 (Ellis Dec.). Managing all sources of mortality affecting the Columbia river spring Chinook listed population (evolutionarily significant unit or ESU) is challenging and a matter to which the four Columbia River Treaty Tribes have dedicated tremendous resources. These early season impacts have a great effect on the tribes. Under its Treaty of June 9, 1855, 12 Stat. 945, the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation (Umatilla Tribe) reserved for itself and its members the right to take fish at all usual and accustomed stations. Pursuant to the Treaty, members of the Umatilla Tribe have exercised and do exercise off-reservation treaty rights at usual and accustomed fishing places on the Columbia River and its tributaries. The Yakama Nation and Warm Springs Tribes have similar reserved rights and similarly exercise those rights. See Yakama Treaty of June 9, 1855, 12 Stat. 951. The Supreme Court of the United States has repeatedly recognized the significance of the treaty right to fish at

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

10

usual and accustomed places, holding that the right is not much less necessary to the existence of the Indians than the atmosphere they breathed. Washington v. Washington State Comml Pass. Fishing Vessel, 443 U.S. 658, 680, 99 S.Ct. 3055, 3071-3072 (1978), quoting United States v. Winans, 198 U.S. 371, 380 (1905). The Umatilla Tribe also protects these treaty rights as a plaintiff in United States v. Oregon, CV 68-513-KI, and is a signatory to the 2008-2017 United States v. Oregon Management Agreement (MA) adopted as an order of this Court on August 12, 2008. Further, the treaty right to fish at usual and accustomed stations is a property right, protected by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution. See Muckleshoot Indian Tribe v. United States Army Corp of Engineers, 698 F.Supp. 1504, 1510 (W.D. Wash. 1988), citing Menominee Tribe of Indians v. United States, 39 1 U.S. 404, 411-412, 88 S.Ct. 1705, 1710-1711 (1968). The point of all this is to emphasize the importance of salmon and salmon restoration to the Tribes. It is fair to say that no agency, department, individual or sovereign has done more for salmon and salmon restoration that the Columbia River Treaty Tribes. Tribal members have fished on the Columbia River for subsistence, ceremonial and commercial purposes since time immemorial. Tribal culture reveres salmon, which is the First Food served at ceremonial meals. 5 In the hierarchy of salmon, the spring Chinook play a special role. The early returning fish are those used in the Tribes ceremonies, and as such, are of immense cultural significance. The more fish the sea lions eat, the longer the Tribes have to wait to conduct their ceremonies in

The Tribes understanding of the environment, and the need to care for it, are exemplified in what the Tribes call First Foods and the order in which Tribes serve these foods. The First Foods include Water, Fish, Big Game, the Roots and the Berries. All of these Foods are part of a context and cannot be separated from one another. The manner in which the Tribes serve them comes from tribal religion, and our serving of the Foods helps remind us of our responsibility to care for the Foods that in the tribal creation belief, promised to take care of the Tribes. The tribal religion, culture, and Foods are therefore inter-dependent, and cannot be separated. All of these Foods, and access to them, are protected by each Tribes 1855 Treaty; the Tribes retain rights to water, the right to fish, to hunt, and to gather these Foods. While based in tribal creation belief that these foods promised themselves to the tribes in this order, the serving order also elegantly incorporates spatial and phenological relationships that are used to focus management efforts on ecological processes that produce and sustain First Foods.

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

11

their longhouses. Further, no other tribal fisheries may occur until the tribal long houses are supplied. In recent years, the salmon return later in the spring, making the tribes wait longer. Ellis Dec. 14. As Antone Minthorn, tribal elder and former Chairman of the Umatilla Tribe explains: The importance of the first salmon ceremony has to do with the celebration of life, of the salmon as subsistence, meaning that the Indians depend upon the salmon for their living. And the annual celebration is just that - it's an appreciation that the salmon are coming back. It is again the natural law; the cycle of life. It's the way things are and if there was no water, there would be no salmon, there would be no cycle, no food. And the Indian people respect it accordingly. http://www.critfc.org/text/ceremony.html Salmon have been a source of sustenance, a gift of religion, and a foundation of culture for the Tribes since time immemorial. Their existence is vital and linked to that of the Tribes. The Tribes are not just another consumer of salmon in the Columbia River. Pl. Br. at 1. Any disproportionate impacts to early runs, whether in terms of delay or possible catastrophic impacts to individual populations, harms the ability of the Tribes to honor their ceremonies, and in so doing their spiritual and cultural beliefs.

D. PLAINTIFFS MISCHARACTERIZE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT IN THE COLUMBIA RIVER Contrary to Plaintiffs contention, fisheries are not uncontrolled in the Columbia River. Rather, a complex judicial and administrative scheme has evolved to regulate the harvest of Columbia River salmon and steelhead. United States v. Oregon, 913 F. 2d 576, 579 (9th Cir. 1990)(approving 1988 10-year management agreement and consent decree). These fish travel hundreds of miles along an arduous migratory route and are very valuable. Idaho ex rel. Evans v. Oregon, 444 U.S. 380, 382, 100 S.Ct. 616, 618, 62 L.Ed.2d 564 (1980). United States v. Oregon MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION 12

is the forum for allocating the harvest of fish that enter the Columbia River system. See id., citing, United States v. Oregon, 699 F.Supp. 1456, 1458-60 (D.Or. 1988); Comment, Sohappy v. Smith: Eight Years of Litigation Over Indian Fishing Rights, 56 Or.L.Rev. 680 (1977). The parties to United States v. Oregon include the states of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, and the four Columbia River treaty tribes (Yakama, Nez Perce, Umatilla and Warm Springs). In 2008, the parties to United States v. Oregon concluded many years of negotiations and entered into the 2008-2017 United States v. Oregon Management Agreement. On September 12, 2008 the Hon. Garr M. King entered a stipulated order approving the Management Agreement as an Order of the Court. A copy of the Management Agreement may be found at http://www.critfc.org/text/press/2008-17USvOR_Mngmt_Agrmt.pdf. The parties coordinated regulation of the Columbia River fisheries they manage are governed by the terms of the Management Agreement. The plaintiffs wrongfully assert (repeatedly) that Columbia River fisheries are not in fact well-controlled. 6 Pl. Br. at p. 18. (Emphasis in original.) See also, pp. 9, 19. Plaintiffs argument is both misdirected and misleading. It is misdirected because the U.S. District Court of Oregon has retained continuing jurisdiction over the United States v. Oregon parties and their implementation of the Management Agreement. Any challenges to the parties administration of the Management Agreement, including NMFS, would necessarily implicate the continuing jurisdiction of the United States v. Oregon court. The harvest numbers and alleged adjustments to harvest quotas cited by the Plaintiffs

In discussing harvest throughout Columbia River, Plaintiffs continue their apples-to-oranges comparison. Nevertheless, we address and correct Plaintiffs misleading arguments with respect to the nature and management of those fisheries.

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

13

(Id.) are misleading, because Columbia River fisheries in the spring management period use an abundance-based harvest framework that reduces the allowed fishery impacts on ESA listed fish at low abundance levels, which is the opposite what occurs with CSL predation. Logically, CSL predation on listed fish occurs at a higher percentage when the run size is low, because such predation is itself uncontrolled. See, Figure 2 and pp. 8-9, above. See also, Hatch Dec. 10; Ellis Dec. 5-6. The way the abundance based fishery works is that once the fishery target harvest impact rate is determined as the run sizes are calculated, then the fishery managers make a policy choice as to how to allocate allowable ESA impacts between treaty and non-treaty fisheries, what gear types to use, what locations and time periods to fish in, and whether or not to use mark selective fisheries. 7 Ellis Dec. 5. Plaintiffs cherry pick data from the last four years for their claim that fisheries are unmanageable. Pl. Br. at 9, 18-19. Annual allowable harvest and actual harvest for both Upper Columbia River spring Chinook and Snake River spring/summer Chinook ESA listed fish are displayed in Table 4 below for each year since 2002, the year the current system began. In only two of those years, 2008 and 2010, did the fisheries exceed the allowable harvest impacts on listed fish. Further, in some years, harvest was well below allowable impacts. Ellis Dec. 6, 18 and Table 2 therein. \\\

The use of mark selective fisheries is simply a tool that allows access to higher levels of ad-clipped hatchery fish than would be possible to catch per unit of mortality of wild fish. It is not correct to assume that mark selective fisheries are a conservation tool. Mark selective fisheries cannot by themselves set or reduce harvest impacts to wild stocks. NMFS has encouraged the use of mark selective fisheries simply because they recommend higher harvest rates on hatchery stocks in the mainstem. It should be noted that there are also significant tributary treaty and nontreaty fisheries targeting these same hatchery fish and intensive mainstem mark selective fisheries can preclude some tributary fishing opportunity. The key point is that decisions about the utility of using mark selective fisheries is a completely separate process from determining what the overall allowed harvest impact on ESA listed fish should be.

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

14

Table 4. Allowed and actual harvest rates on Columbia River wild spring Chinook L M N O P Actual total Actual total Harvest Harvest Rate Rate on Natural on Natural Origin ESA Listed Upper Snake River Allowed Total Harvest rate Columbia Spring/Summer Harvest on ESA Listed Fish in Year Rate Spring Chinook Chinook Zone 1-5 Fisheries 2002 12%* 12.6%* 12.4%* 1.7% 2003 12% 9.6% 9.5% 1.5% 2004 11% 10.9% 10.8% 1.9% 2005 9% 7.9% 7.9% 1.6% 2006 10% 7.9% 7.9% 1.3% 2007 9% 8.2% 8.1% 1.1% 2008 11% 15.9% 15.9% 2.4% 2009 11% 10.4% 10.2% 2.9% 2010 13% 16.8% 16.7% 3.4% 2011 12% 8.7% 8.8% 2.3% *Incidental Take Statement presumes actual total harvest rate may be up to 0.8% higher than allowed harvest rate. Id. It is also incorrect to speak in terms of quotas or to say that fisheries were initially permitted x% and then downgraded. See Pl. Br. at 9. Fisheries are limited by the actual river mouth run sizes. The co-managers may initially plan for higher harvest rates based on preseason forecasts, but the managers know that this can change and runs sizes can be less than forecast. In all but those two years, the co-managers reacted to run size changes up or down and managed total treaty and non-treaty harvest to stay within allowed ESA limits. Ellis Dec. at 5,6,9. Plaintiffs also imply that for those years the harvest did exceed its allowable impacts, there should be some off-setting penalty in later years. While this might work for fisheries that target species that reproduce multiple times, plaintiffs overlook the fact that salmon are subject to harvest interception just one season the year they return to the river before they spawn and

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

15

die. In the case of Columbia River harvest, such penalties would serve little to no biological purpose. Ellis Dec. 7. E. PLAINTIFFS GENERALIZATIONS REGARDING HATCHERY AND NONNATIVE FISH ARE GROSSLY MISLEADING Plaintiffs gross characterization of hatchery effects is grossly outdated and misleading. Pl. Br. at 9-10. There are different types of hatchery fish that serve a variety of purposes. Many hatchery fish are produced as mitigation for the effects of the development of the Columbia River hydro system, as well as other development activities that have blocked or damaged habitat and reduced the productivity of remaining wild fish. Additionally, hatcheries now play an important role in the actual work of restoring natural fish populations. Supplementation hatcheries are used specifically to produce fish that are allowed to spawn naturally which can increase the abundance of natural origin fish. The risk of adverse genetic introgression effects from such hatcheries is low and well-managed. Indeed, supplementation hatcheries are now part of the restoration strategy for many stocks. Contrary to the plaintiffs assertions, fish diseases are naturally occurring and those occurring in hatchery populations are aggressively managed and controlled. Declaration of Peter F. Galbreath (Galbreath Dec.) 3-6 and publications cited therein. Unlike CSL predation, hatchery practices are regularly modified through an adaptive management process. Columbia basin managers use an active adaptive management approach to plan and implement hatchery production in ways that meet harvest and conservation objectives, while minimizing risk to natural populations. Hatchery fish provide numerous benefits to society. Galbreath Dec. 2.

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

16

Plaintiffs also claim that predation by stocked non-native fish, such as bass and walleye could equal or exceed impacts from hydro-power, fisheries, hatcheries, and habitat. Pl. Br. at 10. (Emphasis in original.) The use of the word stocked implies these fish were stocked by management agencies. In truth, bass and walleye have not been purposefully stocked by the states into the waters of the Columbia River. Rather, they have been illegally introduced into these waters. Unfortunately, there are no known reasonable management actions that can be done to significantly reduce or eliminate the adverse impacts from these fish as a result of their illegal introduction that. Contrast this situation with CSL predation a problem for which there is a ready solution, which NMFS and the states are appropriately employing. Ellis Dec. 13. III. CONCLUSION

For all the reasons discussed above these Tribes respectfully request that the Court deny Plaintiffs Motion for Preliminary Injunction and allow the lethal removal program to continue. Respectfully submitted, DATED this 20th day of April, 2012. s/Brent H. Hall Brent H. Hall, OSB# 992762 brenthall@ctuir.com TEL: (541) 429-7407 FAX: (541) 429-7407 Of Attorneys for Applicant Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation s/Thomas A. Zeilman Thomas A. Zeilman, WSBA # 28470 tzeilman@qwestoffice.net TEL: (509) 575-1500 FAX: (509) 575-1227 Attorney for Applicant Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

17

s/John W. Ogan John W. Ogan, OSB#06594 jwo@karnopp.com TEL: (541) 382-3011 FAX: (541) 383-3073 Of Attorneys for Applicant Confederated Tribes of the Warms Springs Reservation of Oregon

MEMORANDUM OF UMATILLA, YAKAMA AND WARM SPRINGS TRIBES IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

18

Você também pode gostar

- FAQ - Firearms in The Capitol 20150128-3Documento1 páginaFAQ - Firearms in The Capitol 20150128-3capitolcurrentsAinda não há avaliações

- Department of Revenue: Suspense IA RecommendationsDocumento6 páginasDepartment of Revenue: Suspense IA RecommendationsStatesman JournalAinda não há avaliações

- Alaska Marriage Stay DeniedDocumento1 páginaAlaska Marriage Stay DeniedEquality Case FilesAinda não há avaliações

- 2012 Ballot MeasuresDocumento1 página2012 Ballot MeasurescapitolcurrentsAinda não há avaliações

- 2012 - SCIClosure Talking PointsDocumento1 página2012 - SCIClosure Talking PointscapitolcurrentsAinda não há avaliações

- 2011-4-11 Nelson Golden Gobbler Award Reception Staff AdviceDocumento2 páginas2011-4-11 Nelson Golden Gobbler Award Reception Staff AdvicecapitolcurrentsAinda não há avaliações

- Niswender EmailDocumento1 páginaNiswender EmailcapitolcurrentsAinda não há avaliações

- Electronic Version of Proposed Rules For 2011-12Documento31 páginasElectronic Version of Proposed Rules For 2011-12capitolcurrentsAinda não há avaliações

- Still To CountDocumento1 páginaStill To CountcapitolcurrentsAinda não há avaliações

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)No EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Nota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNo EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNo EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNo EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNo EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (345)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNo EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNo EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNo EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNo EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNo EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNo EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNo EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnNota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNo EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyNota: 3.5 de 5 estrelas3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNo EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreNota: 4 de 5 estrelas4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)No EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Nota: 4.5 de 5 estrelas4.5/5 (121)

- Flamingo Class XIIDocumento107 páginasFlamingo Class XIIsathya_41095Ainda não há avaliações

- NCERT Class 12 English Deep WaterDocumento9 páginasNCERT Class 12 English Deep WaterAshmira MishraAinda não há avaliações

- GSMDocumento11 páginasGSMdustboyAinda não há avaliações

- White Magic 9781951142407 9781951142391Documento313 páginasWhite Magic 9781951142407 9781951142391crevette.ninjaAinda não há avaliações

- Notice: Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects Inventory, Repatriation, Etc.Documento3 páginasNotice: Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects Inventory, Repatriation, Etc.Justia.comAinda não há avaliações

- NCERT Class 12 English Part 2Documento118 páginasNCERT Class 12 English Part 2Jaymala ShelkeAinda não há avaliações

- The Last Lesson: Alphonse DaudetDocumento106 páginasThe Last Lesson: Alphonse DaudetNikhil KumarAinda não há avaliações

- Notice: Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects Inventory, Repatriation, Etc.Documento2 páginasNotice: Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects Inventory, Repatriation, Etc.Justia.comAinda não há avaliações

- Notice: Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects Inventory, Repatriation, Etc.Documento3 páginasNotice: Native American Human Remains, Funerary Objects Inventory, Repatriation, Etc.Justia.comAinda não há avaliações

- The Gift of Knowledge / Ttnúwit Átawish Nch'inch'imamí: Reflections On Sahaptin WaysDocumento28 páginasThe Gift of Knowledge / Ttnúwit Átawish Nch'inch'imamí: Reflections On Sahaptin WaysUniversity of Washington Press100% (1)

- Notice: Environmental Statements Availability, Etc.: Thomas Burke Memorial Museum, University of Washington, Seattle, WADocumento2 páginasNotice: Environmental Statements Availability, Etc.: Thomas Burke Memorial Museum, University of Washington, Seattle, WAJustia.comAinda não há avaliações

- s11160 020 09627 7 PDFDocumento42 páginass11160 020 09627 7 PDFLendry NormanAinda não há avaliações

- American Indian Tribal List - Native American Tribes and LanguagesDocumento8 páginasAmerican Indian Tribal List - Native American Tribes and Languagesdarksolomon100% (1)