Escolar Documentos

Profissional Documentos

Cultura Documentos

10 Rules of Economics

Enviado por

James GrahamDescrição original:

Direitos autorais

Formatos disponíveis

Compartilhar este documento

Compartilhar ou incorporar documento

Você considera este documento útil?

Este conteúdo é inapropriado?

Denunciar este documentoDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

10 Rules of Economics

Enviado por

James GrahamDireitos autorais:

Formatos disponíveis

The 10 basic rules of economics Definitions Money is a meduim of exchange wherein money represents value.

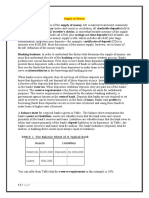

No bartering nece ssary Governments print or coin money. How much money is in existence is totally up t o the government. In the United States, money is controlled by the Federal Reserve, not the Treasu ry. It's not a simple thing to pay off Treasury bills with new money. Banks increase the money supply by savings and borrowings. When one person puts money into the bank as savings, another person takes the same money out as borr owings. Both people have access to the same dollar. This is how the bank pays interest on savings and CDs A run on the bank occurs when many people come in to the bank to withdraw their money. Since the bank loans out most money deposited with the bank, if too many people come in to get their savings or checking money, the bank can't pay them all. In this day and age, with some customers having millions or even billions in a bank, a run on the bank can happen with just a few customers. That is what happened with Bear Stearns and with Lehman Brothers. Banks have "reserve requirements", which require the bank to keep a portion of t heir total assets as reserves instead of making loans with all of their assets If a bank opens with 1 million dollars, and has a reserve requirement of 10%, ho w much money can it lend? $900,000? $909,090? The answer is $10,000,000! How is that possible? The bank holds the entire $1 million in reserve, and then bo rrows $10,000,000 from other banks and loans that out. Why is that important? If the bank lent out $909,090, then if loans went bad, b anks would be losing deposits, which would be offset by interest from the other loans. However, in the $10,000,000 scenario, the bank has to make payments on i ts loan! The loss is felt immediately, instead of when the depositor asks for h is money back. Rules 1 - Inflation is more money competing for a given amount of goods and services 2 - Deflation is less money comepting for a given amount of goods and services 3 - Inflation is usually caused by governments making too much money 4 - If there is not enough money, prices can drop even though there is no major economic shift. This can be esacerbated by price increases in a necessary commo dity, such as wheat, corn, or oil. 5 - Deflation can occur from a reduction in the cost to make goods and services* , or from money disapperaring from the economy 6 - If costs are dropping and companies are losing money, deflation is occuring. What is causing the deflation is immaterial 7 - Newfangled financial derivatives made it possible to buy more houses, at hig

her prices, and turn home equity into spendable money. The value of US homes wa s 25 trillion in 2008, while the loan capacity of US banks in 2008 was

Alison from Zillow here. To answer your question Zillow calculated the combined value of all homes across the US as of December 31, 2008. Our data shows that th e values amount to about $25.1 trillion. Money multiplier From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In monetary economics, a money multiplier is one of various closely related rati os of commercial bank money to central bank money under a fractional-reserve ban king system.[1] Most often, it measures the maximum amount of commercial bank mo ney that can be created by a given unit of central bank money. That is, in a fra ctional-reserve banking system, the total amount of loans that commercial banks are allowed to extend (the commercial bank money that they can legally create) i s a multiple of reserves; this multiple is the reciprocal of the reserve ratio, and it is an economic multiplier.[2] If banks lend out close to the maximum allowed by their reserves, then the inequ ality becomes an approximate equality, and commercial bank money is central bank money times the multiplier. If banks instead lend less than the maximum, accumu lating excess reserves, then commercial bank money will be less than central ban k money times the multiplier. In the United States since 1959, banks lent out close to the maximum allowed for the 49-year period from 1959 until August 2008, maintaining a low level of exce ss reserves, then accumulated significant excess reserves over the period Septem ber 2008 through the present (November 2009). Thus, in the first period, commerc ial bank money was almost exactly central bank money times the multiplier, but t his relationship broke down from September 2008. For example, with the reserve ratio of 20 percent, this reserve ratio, RR, can a lso be expressed as a fraction RR=1/5 So then the money multiplier, m, will be calculated as: m = 1/(1/5) = 5 This number is multiplied by the initial deposit to show the maximum amount of m oney it can be expanded to.[11] Another way to look at the monetary multiplier is derived from the concept of mo ney supply and money base. It is the number of dollars of money supply that can be created for every dollar of monetary base. Money supply, denoted by M, is the stock of money held by public. It is measured by the amount of currency and dep osits. Money Base, denoted by B, is the summation of currency and reserves. Curr ency and Reserves are monetary policy that can be affected by the Federal Reserv e. For example, the Federal Reserve can increase currency by printing more money and they can similarly increase reserve by requiring a higher percentage of dep osits to be stored in the Federal Reserve.

Mathematically: M=C+D B=C+R M=Money Supply C=Currency D=Deposits B=Money Base R=Reserve So that money supply over money base: M/B = (C+D)/(C+R)\ Multiply the right side by [(D/CR) / (D/CR)]. Since this equals to 1, it is math ematically justified to multiply it to only the right side. Then multiple the right side of the equation by the Money Base So we get: M=B * [(D/R)(1+D/C) / (D/R + D/C)] [(D/R)(1+D/C) / (D/R + D/C)] is the multiplier. Therefore, if money base is held constant, the ratio of D/R and D/C affects the money supply. When the ratio of deposits to reserves (D/R) reduces, the multiplier reduces. Similarly, if the ra tio of deposits to currency (D/C) falls, the multiplier falls as well. [nb 1] The multiplier effect is relevant to considering monetary and fiscal policies, a s well how the banking system works. For example, the deposit, the monetary amou nt a customer deposits at a bank, is used by the bank to loan out to others, the reby generating the money supply. Most banks are FDIC insured (Federal Deposit I nsurance Corporation), so that customers are assured that their savings, up to a certain amount, is insured by the federal government. Banks are required to res erve a certain ratio of the customer's deposits in reserve, either in the form o f vault cash or of a deposit maintained by a Federal Reserve Bank.[1] . Therefor e, if the Federal Reserve Bank (and hence its monetary policy) requires a higher percentage of reserve, then it lowers the bank's financial ability to loan. Implications for monetary policy See also: Monetary policy The multiplier plays a key role in monetary policy, and the distinction between the multiplier being the maximum amount of commercial bank money created by a gi ven unit of central bank money and approximately equal to the amount created has important implications in monetary policy. If banks maintain low levels of excess reserves, as they did in the US from 1959 to August 2008, then central banks can finely control broad (commercial bank) m oney supply by controlling central bank money creation, as the multiplier gives a direct and fixed connection between these. If, on the other hand, banks accumulate excess reserves, as occurs in some finan cial crises such as the Great Depression and the Financial crisis of 2007 2010, th en this relationship breaks down and central banks can force the broad money sup ply to shrink, but not force it to grow. Restated, increases in central bank money may not result in commercial bank mone y because the money is not required to be lent out it may instead result in a gr owth of unlent reserves (excess reserves). This situation is referred to as "pus hing on a string": withdrawal of central bank money compels commercial banks to curtain lending (one can pull money via this mechanism), but input of central ba nk money does not compel commercial banks to lend (one cannot push via this mech anism).

This described growth in excess reserves has indeed occurred in the Financial cr isis of 2007 2010, US bank excess reserves growing over 500-fold, from under $2 bi llion in August 2008 to over $1,000 billion in November 2009. (Note from me - ma tters have been made worse by extra requirements put on by the FDIC; witness wha t happened to ShoreBank. Since the insurers are not the same as the central ban k, the central bank and the insurers can adopt different policies which makes th is situation MUCH worse).

Você também pode gostar

- Case, Fair and Oster Chapter 10 Problems Money Supply and Federal ReserveDocumento3 páginasCase, Fair and Oster Chapter 10 Problems Money Supply and Federal ReserveRayra AugustaAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 21 (19th Jan, 2009)Documento16 páginasLecture 21 (19th Jan, 2009)sana ziaAinda não há avaliações

- The Problem of Fractional Reserves Banking, Parts Two and ThreeDocumento16 páginasThe Problem of Fractional Reserves Banking, Parts Two and Threepater eusebius tenebrarumAinda não há avaliações

- Ch30 Notetaking GuideDocumento12 páginasCh30 Notetaking Guidedrivestash528491Ainda não há avaliações

- Tche 303 - Money and Banking Tutorial 9: CurrencyDocumento4 páginasTche 303 - Money and Banking Tutorial 9: CurrencyNguyen VyAinda não há avaliações

- Money Is Defined As Any Asset That People Are Willing To Accept in Exchange For Goods andDocumento4 páginasMoney Is Defined As Any Asset That People Are Willing To Accept in Exchange For Goods andVũ Hồng PhươngAinda não há avaliações

- The Banking System and The Money SupplyDocumento5 páginasThe Banking System and The Money SupplybhaveshvmlAinda não há avaliações

- Note On Monet PolDocumento21 páginasNote On Monet Polaudace2009Ainda não há avaliações

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocumento9 páginasNew Microsoft Word DocumentAnonymous 4yUG6uhmgAinda não há avaliações

- The Money Supply Process and The Money MultipliersDocumento18 páginasThe Money Supply Process and The Money MultipliersLekhutla TFAinda não há avaliações

- Money Creation and The Banking SystemDocumento14 páginasMoney Creation and The Banking SystemminichelAinda não há avaliações

- ECON1132 Final 2013springDocumento5 páginasECON1132 Final 2013springexamkillerAinda não há avaliações

- How Do Banks Work and How Do They Make A Profit? (4 Marks)Documento13 páginasHow Do Banks Work and How Do They Make A Profit? (4 Marks)Mohamed ShaniuAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Money SupplyDocumento3 páginasFactors Affecting Money Supplycuriben100% (5)

- Ec103 Week 07 and 08 s14Documento31 páginasEc103 Week 07 and 08 s14юрий локтионовAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 1: Fractional Reserve BankingDocumento4 páginasAssignment 1: Fractional Reserve BankingArcha ShajiAinda não há avaliações

- Factors Affecting Money SupplyDocumento3 páginasFactors Affecting Money Supplyananya50% (2)

- The Money Supply and The Federal Reserve SystemDocumento18 páginasThe Money Supply and The Federal Reserve SystemYuri AnnisaAinda não há avaliações

- Econ Notes 3Documento13 páginasEcon Notes 3Engineers UniqueAinda não há avaliações

- Introduction To The Money SupplyDocumento3 páginasIntroduction To The Money SupplyamitwaghelaAinda não há avaliações

- Econ Assignment 3Documento3 páginasEcon Assignment 3gwanagbu9Ainda não há avaliações

- Monetary PolicyDocumento46 páginasMonetary PolicyTanvi Shukla (Yr. 21-23)Ainda não há avaliações

- Do Budget Deficits Cause in Ation?: by Keith SillDocumento8 páginasDo Budget Deficits Cause in Ation?: by Keith SillluminaAinda não há avaliações

- Imsb T6Documento5 páginasImsb T6Lyc Chun100% (2)

- THE MONETARY SYSTEM Chapter 29Documento5 páginasTHE MONETARY SYSTEM Chapter 29HoàngTrúcAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter Fifteen Money and Banking: Answers To End-Of-Chapter QuestionsDocumento7 páginasChapter Fifteen Money and Banking: Answers To End-Of-Chapter QuestionsnickAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 16Documento6 páginasChapter 16Marvin Strong100% (1)

- Central BankDocumento6 páginasCentral Bank0115Nurul Haque EmonAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment On Marco EconomicsDocumento9 páginasAssignment On Marco EconomicsMosharraf HussainAinda não há avaliações

- Summary of Anthony Crescenzi's The Strategic Bond Investor, Third EditionNo EverandSummary of Anthony Crescenzi's The Strategic Bond Investor, Third EditionAinda não há avaliações

- $bank NotesDocumento3 páginas$bank NotesKatriel HeartsBigbangAinda não há avaliações

- GR Fed Hidden Agenda-Drive Into DepressionDocumento8 páginasGR Fed Hidden Agenda-Drive Into Depressionanon_717974Ainda não há avaliações

- Ruby NewDocumento3 páginasRuby Newapi-26570979Ainda não há avaliações

- SeatworkDocumento3 páginasSeatworkMs VampireAinda não há avaliações

- The Money Supply and Money MultiplierDocumento22 páginasThe Money Supply and Money MultiplierNandiniAinda não há avaliações

- Worksheet - Money and Monetary PolicyDocumento3 páginasWorksheet - Money and Monetary PolicybrianAinda não há avaliações

- Lecture 1: Basics of Central Banks & Monetary Policy: Harjoat S. BhamraDocumento68 páginasLecture 1: Basics of Central Banks & Monetary Policy: Harjoat S. Bhamranicola0808Ainda não há avaliações

- Last Resort: The Financial Crisis and the Future of BailoutsNo EverandLast Resort: The Financial Crisis and the Future of BailoutsAinda não há avaliações

- Econ CH 10Documento16 páginasEcon CH 10BradAinda não há avaliações

- Assignment 1Documento6 páginasAssignment 1Ken PhanAinda não há avaliações

- CH 29Documento36 páginasCH 29Robelen CallantaAinda não há avaliações

- Important Notes For Midterm 2Documento11 páginasImportant Notes For Midterm 2Abass Bayo-AwoyemiAinda não há avaliações

- Liquidity Crises: Understanding Sources and Limiting Consequences: A Theoretical FrameworkDocumento10 páginasLiquidity Crises: Understanding Sources and Limiting Consequences: A Theoretical FrameworkAnonymous i8ErYPAinda não há avaliações

- The Supply of MoneyDocumento12 páginasThe Supply of MoneyJoseph OkpaAinda não há avaliações

- 6 Money SupplyDocumento6 páginas6 Money SupplySaroj LamichhaneAinda não há avaliações

- Short-Answer ProblemsDocumento4 páginasShort-Answer ProblemsChristine HewAinda não há avaliações

- Tche 303 - Money and Banking Tutorial 9Documento3 páginasTche 303 - Money and Banking Tutorial 9Phương Anh TrầnAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 7Documento17 páginasChapter 7Yasin IsikAinda não há avaliações

- China and the US Foreign Debt Crisis: Does China Own the USA?No EverandChina and the US Foreign Debt Crisis: Does China Own the USA?Ainda não há avaliações

- Towards a Viable Monetary System: The Need for a National Complementary Currency for the United StatesNo EverandTowards a Viable Monetary System: The Need for a National Complementary Currency for the United StatesAinda não há avaliações

- Final Review Answer KeyDocumento6 páginasFinal Review Answer KeyKhanh Ngan PhanAinda não há avaliações

- Macro - EconomicsDocumento28 páginasMacro - EconomicsFarabi GulandazAinda não há avaliações

- The Great Recession: The burst of the property bubble and the excesses of speculationNo EverandThe Great Recession: The burst of the property bubble and the excesses of speculationAinda não há avaliações

- Johnny FinalDocumento4 páginasJohnny FinalNikita SharmaAinda não há avaliações

- Macro 7Documento12 páginasMacro 7Àlex SolàAinda não há avaliações

- Money SupplyDocumento12 páginasMoney SupplyAmanda RuthAinda não há avaliações

- MACROECONOMICS, 7th. Edition N. Gregory Mankiw Mannig J. SimidianDocumento21 páginasMACROECONOMICS, 7th. Edition N. Gregory Mankiw Mannig J. SimidianAnsoy AvesAinda não há avaliações

- Case Digest On SALES LAW PDFDocumento21 páginasCase Digest On SALES LAW PDFleoAinda não há avaliações

- Invitation For Bids: Single-Stage: Two-EnvelopeDocumento3 páginasInvitation For Bids: Single-Stage: Two-EnvelopeAhmad ButtAinda não há avaliações

- KKR Private Equity Investors, L.P. Annual Report 2006Documento84 páginasKKR Private Equity Investors, L.P. Annual Report 2006AsiaBuyoutsAinda não há avaliações

- State VA BenefitsDocumento52 páginasState VA BenefitsEd BallAinda não há avaliações

- Chapter 4 For FilingDocumento9 páginasChapter 4 For Filinglagurr100% (1)

- Standalone & Consolidated Financial Results, Auditors Report For March 31, 2016 (Result)Documento16 páginasStandalone & Consolidated Financial Results, Auditors Report For March 31, 2016 (Result)Shyam SunderAinda não há avaliações

- HDFC ServicesDocumento16 páginasHDFC ServicesVenkateshwar Dasari NethaAinda não há avaliações

- First Division G.R. No. 184458, January 14, 2015: Supreme Court of The PhilippinesDocumento19 páginasFirst Division G.R. No. 184458, January 14, 2015: Supreme Court of The PhilippinesSocAinda não há avaliações

- Financial Management Module I: Introduction: Finance and Related DisciplinesDocumento4 páginasFinancial Management Module I: Introduction: Finance and Related DisciplinesKhushbu SaxenaAinda não há avaliações

- Study of Personal Loan and Analysis of People Perception On HDFC & Sbi BankDocumento7 páginasStudy of Personal Loan and Analysis of People Perception On HDFC & Sbi BankImtiyazAli SiddiqueAinda não há avaliações

- Retirement of A PartnerDocumento6 páginasRetirement of A Partnershrey narulaAinda não há avaliações

- G.R. No. L-45710 October 3, 1985Documento1 páginaG.R. No. L-45710 October 3, 1985Vin LacsieAinda não há avaliações

- Montenegro Investment OpportunitiesDocumento41 páginasMontenegro Investment Opportunitiesassassin011Ainda não há avaliações

- Dutch Bangla Bank Ltd.Documento19 páginasDutch Bangla Bank Ltd.Bikash Saha100% (1)

- Harsh ElectricalsDocumento8 páginasHarsh Electricalsmayank.dce123Ainda não há avaliações

- sAP Receivables Management Credit and CollectionsDocumento46 páginassAP Receivables Management Credit and CollectionsPromoth Jaidev100% (1)

- Interest Q'sDocumento11 páginasInterest Q'sMuhammad Noor AmerAinda não há avaliações

- The Role of SHGS in Financial Inclusion. A Case Study: Uma .H.R, Rupa.K.NDocumento5 páginasThe Role of SHGS in Financial Inclusion. A Case Study: Uma .H.R, Rupa.K.NDevikaAinda não há avaliações

- RM Questionnaire For Bank Customer Satisfaction - Pranotee WorlikarDocumento5 páginasRM Questionnaire For Bank Customer Satisfaction - Pranotee WorlikarSasha SGAinda não há avaliações

- 2022list of LC - 0331 PDFDocumento45 páginas2022list of LC - 0331 PDFEden AguinaldoAinda não há avaliações

- Public Information Request From TX OAGDocumento20 páginasPublic Information Request From TX OAGKristina BrunnerAinda não há avaliações

- Nsel ScamDocumento13 páginasNsel Scamkinjalkapadia087118Ainda não há avaliações

- 2018F SUP 3043 - 1 Assignment #1Documento8 páginas2018F SUP 3043 - 1 Assignment #1Breno Duarte TiradoAinda não há avaliações

- Modes Cvedil de Liuey: HypothecalionDocumento6 páginasModes Cvedil de Liuey: Hypothecalionsohail shaikAinda não há avaliações

- Application Form: Loan Requested Purpose of Loan DateDocumento2 páginasApplication Form: Loan Requested Purpose of Loan DateZulueta Jing MjAinda não há avaliações

- Imerys Talc Chapter 11 Petition - Includes List of Top 30 Plaintiff FirmsDocumento26 páginasImerys Talc Chapter 11 Petition - Includes List of Top 30 Plaintiff FirmsKirk HartleyAinda não há avaliações

- Tally Inventory Question 6 (Rice Mill)Documento2 páginasTally Inventory Question 6 (Rice Mill)Suraj BiswakarmaAinda não há avaliações

- Jumia Travel, Hotel & Flight Booking - Rates & Pay Later HotelsDocumento2 páginasJumia Travel, Hotel & Flight Booking - Rates & Pay Later Hotelssayys1390Ainda não há avaliações

- CIR Vs Filinvest DigestDocumento17 páginasCIR Vs Filinvest DigestJImlan Sahipa IsmaelAinda não há avaliações

- Ic Mock Exam Set C PDFDocumento11 páginasIc Mock Exam Set C PDFHerson LaxamanaAinda não há avaliações